Groundwater Flow in Low-Permeability Environments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dewatering Behavior of a Wood-Cellulose Nanofibril

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Dewatering Behavior of a Wood- Cellulose Nanofbril Particulate System Received: 6 May 2019 Ezatollah (Nima) Amini1, Mehdi Tajvidi1, Douglas W. Bousfeld2, Douglas J. Gardner1 & Accepted: 26 September 2019 Stephen M. Shaler1 Published: xx xx xxxx The novel use of aqueous suspensions of cellulose nanofbrils (CNF) as an adhesive/binder in lignocellulosic-based composite manufacture requires the removal of a considerable amount of water from the furnish during processing, necessitating thorough understanding of the dewatering behavior referred to as “contact dewatering”. The dewatering behavior of a wood-CNF particulate system (wet furnish) was studied through pressure fltration tests, centrifugation, and characterization of hard-to- remove (HR) water, i.e. moisture content in the wet furnish at the transition between constant rate part and the falling rate part of evaporative change in mass from an isothermal thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). The efect of wood particle size thereby particle specifc surface area on the dewatering performance of wet furnish was investigated. Permeability coefcients of wet furnish during pressure fltration experiments were also determined based on Darcy’s law for volumetric fow through a porous medium. Results revealed that specifc particle surface area has a signifcant efect on the dewatering of wet furnish where dewatering rate signifcantly increased at higher specifc particle surface area levels. While the permeability of the systems decreased over time in almost all cases, the most signifcant portion of dewatering occurred at very early stages of dewatering (less than 200seconds) leading to a considerable increase in instantaneous dewatering when CNF particles come in contact with wood particles. -

Bedrock Dewatering for Construction of Marmet and Soo Lock Projects

Bedrock Dewatering for Construction of Marmet and Soo Lock Projects Michael Nield Engineering Geologist Dam Safety Production Center, Huntington, WV August 2012 US Army Corps of Engineers BUILDING STRONG® BEDROCK DEWATERING FOR CONSTRUCTION OUTLINE 1. Marmet Lock Replacement Project (construction) - Project Description - Site Geology - Permeability and Groundwater Inflow - Dewatering Provisions 2. Soo Lock Replacement Project (design) - Project Description - Site Geology - Permeability and Predicted Groundwater Inflow - Impact to Design BUILDING STRONG® MARMET LOCK - PROJECT DESCRIPTION . Located on Kanawha River, OHIIO RIVER near Charleston, West GREAT LAKES DIVISION Virginia. Permits economic river transportation of coal, MARMET aggregate and chemicals. LOCKS & DAM . Construction of the new replacement lock was completed in 2009 BUILDING STRONG® “Busiest Lock in USA” Prior to New Lock Twin 56’ X 360’ Chambers Completed in 1934 Aerial View – Original Locks BUILDING STRONG® New 110’ X 800’ Lock Chamber Original Locks New Guard Wall New Guide Walls Aerial View – New Replacement Lock BUILDING STRONG® MARMET LOCK - SITE GEOLOGY . 157 TOTAL BORINGS . 10,200’ TOTAL DRILLING . 3,700’ ROCK CORE . 294 PRESSURE TESTS Subsurface Exploration – Boring Location Plan BUILDING STRONG® General Geology . Soil thickness 40 to 60 feet . Relatively flat top of rock surface at elev. 552 ± 3’ . Sedimentary rock of the Pennsylvanian-aged Kanawha Formation Sandstone member (23 to 43 feet thick) Shale member (19 to 33 feet thick) . Low angled bedding with 0o-10o dip to the Northwest . Slightly fractured with occasional high angled joints (70o-90o) BUILDING STRONG® Bedrock Units - Sandstone Member . Light gray . Moderately hard to hard . Medium to fine grained . Average unconfined compressive strength 8,442 psi . -

Dewatering Mechanisms of Compressible Filter Cakes

Dewatering mechanisms of compressible filter cakes Sarah Strubel, Harald Anlauf, Hermann Nirschl, Institute of Mechanical Process Engineering (MVM), Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) For designing filtration processes, a correlation between applied pressure and filter cake saturation is required. This correlation is provided by the capillary pressure curve, and depends on the pore size distribution of the filter cake. Many materials form compressible filter cakes: The porosity - and pore size distribution - changes with applied pressure. To determine the capillary pressure curve, a saturated filter cake is dewatered by gradually increasing the gas pressure. Below the capillary entry pressure the filter cake will consolidate. Above, desaturation of pores will occur in addition to further consolidation. In industrial filtration processes in contrary, the filter cake is subjected to constant gas pressure and therefore consolidation and desaturation occur simultaneously. With desaturation though, the tensile strength of the filter cake and therefore the resistance to consolidation increases. It is therefore interesting to investigate, if desaturation of an already consolidated cake, as in a capillary pressure experiment, will actually result in the same porosity and saturation as in a conventional filtration experiment, where both mechanisms occur at once. In this work, filter cake porosity, saturation and residual moisture are compared for two sets of filtration experiments. The first experiment is a standard filtration test, where the filter cake is formed and desaturated by gas pressure. In the second experiment a filter cake is first formed and consolidated and subsequently desaturated by applying gas pressure to the filter cake. The obtained results show a difference in porosity for the two types of experiments with in all other respects comparable filtration conditions. -

Dewatering – Deep Well Systems

Dewatering – Deep well systems GEO-SLOPE International Ltd. | www.geo-slope.com 1200, 700 - 6th Ave SW, Calgary, AB, Canada T2P 0T8 Main: +1 403 269 2002 | Fax: +1 888 463 2239 Introduction The objective of dewatering is to lower the groundwater table to prevent significant groundwater flow into an excavation, and/or to ensure slope stability. The preferred dewatering system will depend on hydrogeological conditions and construction requirements. In the case of slopes and excavations, the groundwater table can be lowered using a combination of methods, such as deep wells, wellpoints, vacuum wells, and horizontal wells. Deep well systems are often used for dewatering slopes and excavations when large drawdowns are required. This type of system generally consists of an array of pumping wells located near the excavation or slope. The combined effect of the array lowers the groundwater table over a wide area. The active pumping system must be set below the groundwater table whereas the bottom of the wells must be set deep enough to allow flow without excessive head loss. The objective of this example is to illustrate how to model deep well systems in three-dimensional environments, and to verify the water-flow formulation against a well-known benchmark. To do so, the example will discuss a specific deep well system, and provide insight into an approach for modeling pumping wells. Numerical Simulation The deep well system, taken from Mansur and Kaufman’s (1962) chapter on dewatering, consists of a large, 770 foot-long by 370 foot-wide, 40 foot-deep excavation in a 90 foot-deep unconfined sandy aquifer. -

Rotary Vacuum-Drum Filter

Rotary vacuum-drum filter Rotary vacuum filter drum consists of a drum rotating in a tub of liquid to be filtered. The technique is well suited to slurries, and liquids with a high solid content, which could clog other forms of filter. The drum is pre-coated with a filter aid, typically of diatomaceous earth (DE) or Perlite. After pre-coat has been applied, the liquid to be filtered is sent to the tub below the drum. The drum rotates through the liquid and the vacuum sucks liquid and solids onto the drum pre-coat surface, the liquid portion is "sucked" by the vacuum through the filter media to the internal portion of the drum, and the filtrate pumped away. The solids adhere to the outside of the drum, which then passes Oliver-type rotary vacuum-drum filter. a knife, cutting off the solids and a small portion of the filter media to reveal a fresh media surface that will enter the liquid as the drum rotates. The knife advances automatically as the surface is removed. Contents Basic fundamentals Rotary vacuum drum filter Range of application Advantages and limitations Advantages Disadvantages Designs available Belt discharge Scraper discharge Roll discharge String discharge Pre coat discharge Main process characteristics and assessment Heuristics design process Basic operation parameters heuristics Discharge mechanism adjustment heuristics Endless belt Scraper Roll String Pre coat Pre coat filter operation heuristics Advanced blade Necessary post treatment for waste stream for thicker Chlorination UV radiation Ozonation Necessary post treatment for waste stream for clarifier Land reclamation Incineration New Development See also References Further reading External links Basic fundamentals Rotary vacuum drum filter Rotary vacuum drum filter (RVDF), patented in 1872,[1] is one of the oldest filters used in the industrial liquid-solids separation. -

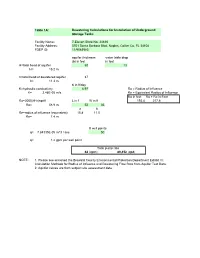

34816 Dewatering Calcs Tables

Table 1A: Dewatering Calculations for Installation of Underground Storage Tanks Facility Name: 7-Eleven Store No. 34816 Facility Address: 3701 Santa Barbara Blvd, Naples, Collier Co, FL 34104 FDEP ID: 11/9063983 aquifer thickness water table drop (b) in feet in feet H=total head of aquifer 50 13 H= 15.2 m h=total head of dewatered aquifer 37 h= 11.3 m K in ft/day K=hydraulic conductivity 6.97 Ro = Radius of Influence K= 2.46E-05 m/s Re = Equivalent Radius of Influence Ro in feet Ro + Re in Feet Ro=3000(H-h)sqrtK L in ft W in ft 193.4 217.8 Ro= 58.9 m 52 36 ab Re=radius of influence (equivalent) 15.8 11.0 Re= 7.4 m # well points q= 7.84335E-05 m^3 / sec 50 q= 1.2 gpm per well point Total pump rate 62 (gpm) 89,452 (gpd) NOTE: 1. Please see enclosed the Broward County Environmental Protection Department Exhibit III: Calculation Methods for Radius of Influence and Dewatering Flow Rate from Aquifer Test Data. 2. Aquifer values are from subject site assessment data. Table 1B: Dewatering Calculations for Installation of Fuel Dispenser Sumps, Product Piping, and Canopy Footers Facility Name: 7-Eleven Store No. 34816 Facility Address: 3701 Santa Barbara Blvd, Naples, Collier Co, FL 34104 FDEP ID: 11/9063983 aquifer thickness water table drop (b) in feet in feet H=total head of aquifer 50 3 H= 15.2 m h=total head of dewatered aquifer 47 h= 14.3 m K in ft/day K=hydraulic conductivity 6.97 Ro = Radius of Influence K= 2.46E-05 m/s Re = Equivalent Radius of Influence Ro in feet Ro + Re in Feet Ro=3000(H-h)sqrtK L in ft W in ft 44.6 81.3 Ro= 13.6 m 132 32 ab Re=radius of influence (equivalent) 40.2 9.8 Re= 11.2 m # well points q= 0.000212597 m^3 / sec 50 q= 3.4 gpm per well point Total pump rate 168 (gpm) 242,463 (gpd) NOTE: 1. -

Dewatering Well Assessment for the Highway Drainage System at Five Sites in the East St

Contract Report 641 Dewatering Well Assessment for the Highway Drainage System at Five Sites in the East St. Louis Area, Illinois (FY94 - Phase 11) by Ellis W. Sanderson, P.E. and Robert D. Olson Prepared for the Illinois Department of Transportation Division of Highways May 1999 Illinois State Water Survey Ground-Water Section Champaign, Illinois A Division of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources DEWATERING WELL ASSESSMENT FOR THE HIGHWAY DRAINAGE SYSTEM AT FIVE SITES IN THE EAST ST. LOUIS AREA, ILLINOIS FY 94 (Phase 11) by Ellis W. Sanderson, P.E., and Robert D. Olson Illinois State Water Survey 2204 Griffith Drive Champaign, IL 61820-7495 Prepared for the Illinois Department of Transportation Division of Highways This report was printed on recycled and recyclable papers. CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION............................................................ 2 Background. .......................................................... 2 Scope of Study......................................................... 2 Physical Setting of Study Area. ........................................... 4 Acknowledgments...................................................... 4 HISTORICAL SUMMARY OF DEWATERING DEVELOPMENT. 9 Horizontal Drain System................................................. 9 Horizontal and Vertical Well Drainage System.. 9 Individual Deep Well Systems............................................. 11 I-70 System. ................................................... -

Monitoring and Numerical Analysis of Pore Water Pressure Changes Eyvashan Dam During the First Dewatering Period

Journal of Applied Research in Water and Wastewater 11(2019) 1-7 Original paper Monitoring and numerical analysis of pore water pressure changes Eyvashan dam during the first dewatering period Behrang Beiranvand*, Mehdi Komasi Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Ayatollah ozma Borujerdi University, Borujerd, Iran. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The performance of dams due to high operating costs and irreparable damages Received 3 November 2018 caused by failures in the construction phase and during the dewatering and Received in revised form 5 February 2019 exploitation period should verified and monitored by proper behavioural analysis. Accepted 9 February 2019 Dewatering the dams will result in the saturation of the embankment and supports and, consequently, the reduction of the stability coefficient. Therefore, in order to allow an earth dam to tolerate the new conditions easily and without problems, the Keywords: Pore water pressure rate of dewatering should be within the range. In this study, pore water pressure in Dewatering the body of Eyvashan earth dam was evaluated. The water level inside the clay Eyvashan earth dam core due to changes in the reservoir water level during the first dewatering and Instrumentation using the actual specifications of the materials by Geostudio and Plaxis software Cut off and compared with the results of the instrumentation in the dam body. In order to adapt the observed and predicted data, a multi-variable regression was used and the coefficient of determination was used and respectively the value of R2=0.9834 and R2=0.9863 was obtained which shows a very good agreement between the observed and predicted data. -

Assessing and Remediating Low Permeability Geologic Materials Contaminated by Petroleum Hydrocarbons from Leaking Underground Storage Tanks: a Literature Review

Assessing And Remediating Low Permeability Geologic Materials Contaminated By Petroleum Hydrocarbons From Leaking Underground Storage Tanks: A Literature Review U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response Office of Underground Storage Tanks Washington, D.C. December 2019 Notice: This document provides technical information to EPA, state, tribal, and local agencies involved in investigating and addressing petroleum releases from leaking underground storage tanks. We obtained this information by reviewing selected literature relating to the occurrence, investigation, behavior, and remediation of contaminants in low permeability geologic materials. This document does not provide formal policy or in any way affect the interpretation of federal regulations. EPA does not endorse or recommend commercial products mentioned in this document, and we do not guarantee performance of methods or equipment mentioned. ii CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 1 Key Takeaways ................................................................................................................... 1 Diffusion .................................................................................................................. 1 Site Characterization .............................................................................................. 2 Heterogeneity ........................................................................................................ -

Dewatering and Basin Draining Fact Sheet (Wq-Strm2-107)

www.pca.state.mn.us Dewatering and Basin Draining National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System/State Disposal System permit guidance on dewatering and basin draining This document is meant to provide guidance on dewatering and basin draining practices of construction sites that are compliant with the Minnesota National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System/State Disposal System (NPDES/SDS) construction stormwater permit (Permit). Definition Dewatering is the removal of surface or ground water to dry and/or solidify a construction site to enable construction activity. Examples of dewatering include pumped discharges, trenches, and ditch cuts that are used for drainage. What is required by the NPDES/SDS Permit? The Minnesota NPDES/SDS Permit regulates the discharge of stormwater. The Permit identifies certain requirements for dewatering and basin draining to effectively prevent and/or control erosion and sediment problems on a construction site. Turbid, or sediment-laden, water that is removed during construction must be released to an onsite sedimentation basin or to a system constructed with appropriate Best Management Practices (BMPs) before the water may be discharged to surface waters. The water must be properly treated or filtered to remove sediment and other contaminants prior to discharge. Dewatering activities must not result in adverse impacts such as nuisance conditions, erosion or scour, flooding, or inundation of wetlands and other surface waters. Energy dissipation BMPs, such as riprap, plastic sheeting, or sand bags, must be installed at the discharge points of the dewatering system for adequate protection from erosion and scouring. Dewatering and basin draining practices must be monitored while in operation, and must not cause nuisance conditions. -

Measurement of Groundwater Table & Pore Water Pressure in Deep

KMS / TECHNICAL DEPARTMENT TECHNICAL NOTE 008 Measurement of Groundwater Table & Pore Water Pressure In Deep Excavations · We excel through experience and learning · Version 02, Jul 2013 Keywords blockage at the outlet. This will lead to a build-up of water Perforated standpipe, standpipe piezometer, groundwater table, pressure, and the water head H2 will become higher than the groundwater movement, excess pore water pressure, hydrostatic head. hydraulic instability Now that if a manometer is placed inside a water tank (with an orifice), the following scenarios can be observed. Synopsis In deep excavations, it is imperative to understand the (i) (iii) (ii) effectiveness of water cut-off provided by the cofferdam walls and/or toe grouting, and also the groundwater movement and pore water pressure both inside and outside the cofferdam. The latter is of particular importance because the build-up of excess pore water pressure on the passive side (excavation side) of the cofferdam walls could lead to hydraulic instability of the cofferdam owing to piping. Water flow 1.0 Introduction Prior to discussing the measurement of groundwater table, pore water pressure, and its relevance to deep excavation, it is perhaps useful to look at the following water In location (i), which is far from the orifice, the water flow flow scenarios and the respective water head measured by a velocity is relatively slow and water is in a near-static condition. manometer. The water level measured by the manometer will practically be the same as the water level in the tank. Whereas in location (ii), which is adjacent to the orifice, water flows at much higher (a) (b) (c) velocity. -

TEMPORARY DEWATERING FEASIBILITY STUDY Redmond Square

REPORT TEMPORARY DEWATERING FEASIBILITY STUDY Redmond Square Submitted to: MGRM LLC 1111 3rd Ave. Suite 2850 Seattle, WA 98101 Submitted by: Golder Associates Inc. 18300 NE Union Hill Road, Suite 200, Redmond, Washington, USA 98052 +1 425 883-0777 1661044.900 November 2019 November 2019 1661044.900 Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 2.0 GEOTECHNICAL REQUIREMENTS .............................................................................................................. 1 2.1 Stratigraphy .......................................................................................................................................... 1 2.2 Primary Aquifer..................................................................................................................................... 2 2.3 Aquifer Transmissivity and Hydraulic Conductivity .............................................................................. 2 2.4 Groundwater Elevations ....................................................................................................................... 2 2.4.1 Historic Record from Nearby Monitoring Wells ............................................................................... 2 2.4.2 Groundwater Levels in On-Site Monitoring Wells ........................................................................... 3 2.5 Potential Construction Dewatering Pumping Rates ............................................................................