Phase II Study of Nilotinib in Melanoma Harboring KIT Alterations Following Progression to Prior KIT Inhibition Richard D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Management of Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia in Pregnancy

ANTICANCER RESEARCH 35: 1-12 (2015) Review Management of Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia in Pregnancy AMIT BHANDARI, KATRINA ROLEN and BINAY KUMAR SHAH Cancer Center and Blood Institute, St. Joseph Regional Medical Center, Lewiston, ID, U.S.A. Abstract. Discovery of tyrosine kinase inhibitors has led to Leukemia in pregnancy is a rare condition, with an annual improvement in survival of chronic myelogenous leukemia incidence of 1-2/100,000 pregnancies (8). Since the first (CML) patients. Many young CML patients encounter administration of imatinib (the first of the TKIs) to patients pregnancy during their lifetime. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors with CML in June 1998, it is estimated that there have now inhibit several proteins that are known to have important been 250,000 patient years of exposure to the drug (mostly functions in gonadal development, implantation and fetal in patients with CML) (9). TKIs not only target BCR-ABL development, thus increasing the risk of embryo toxicities. tyrosine kinase but also c-kit, platelet derived growth factors Studies have shown imatinib to be embryotoxic in animals with receptors α and β (PDGFR-α/β), ARG and c-FMS (10). varying effects in fertility. Since pregnancy is rare in CML, Several of these proteins are known to have functions that there are no randomized controlled trials to address the may be important in gonadal development, implantation and optimal management of this condition. However, there are fetal development (11-15). Despite this fact, there is still only several case reports and case series on CML in pregnancy. At limited information on the effects of imatinib on fertility the present time, there is no consensus on how to manage and/or pregnancy. -

Nilotinib (Tasigna®) EOCCO POLICY

nilotinib (Tasigna®) EOCCO POLICY Policy Type: PA/SP Pharmacy Coverage Policy: EOCCO136 Description Nilotinib (Tasigna) is a Bcr-Abl kinase inhibitor that binds to, and stabilizes, the inactive conformation of the kinase domain of the Abl protein. Length of Authorization Initial: Three months Renewal: 12 months Quantity Limits Product Name Dosage Form Indication Quantity Limit Newly diagnosed OR resistant/ intolerant 50 mg capsules 112 capsules/28 days Ph+ CML in chronic phase nilotinib 150 mg capsules Newly diagnosed Ph+ CML in chronic phase 112 capsules/28 days (Tasigna) Resistant or intolerant Ph + CML 200 mg capsules 112 capsules/28 days Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GIST) Initial Evaluation I. Nilotinib (Tasigna) may be considered medically necessary when the following criteria are met: A. Medication is prescribed by, or in consultation with, an oncologist; AND B. Medication will not be used in combination with other oncologic medications (i.e., will be used as monotherapy); AND C. A diagnosis of one of the following: 1. Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) ; AND i. Member is newly diagnosed with Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) or BCR-ABL1 mutation positive CML in chronic phase; OR ii. Member is diagnosed with chronic OR accelerated phase Ph+ or BCR-ABL1 mutation positive CML; AND a. Member is 18 years of age or older; AND b. Treatment with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor [e.g. imatinib (Gleevec)] has been ineffective, contraindicated, or not tolerated; OR iii. Member is diagnosed with chronic phase Ph+ or BCR-ABL1 mutation positive CML; AND a. Member is one year of age or older; AND 1 nilotinib (Tasigna®) EOCCO POLICY b. -

Tasigna, INN-Nilotinib

ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Tasigna 50 mg hard capsules Tasigna 200 mg hard capsules 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Tasigna 50 mg hard capsules One hard capsule contains 50 mg nilotinib (as hydrochloride monohydrate). Excipient with known effect One hard capsule contains 39.03 mg lactose monohydrate. Tasigna 200 mg hard capsules One hard capsule contains 200 mg nilotinib (as hydrochloride monohydrate). Excipient with known effect One hard capsule contains 156.11 mg lactose monohydrate. For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Hard capsule. Tasigna 50 mg hard capsules White to yellowish powder in hard gelatin capsule with red opaque cap and light yellow opaque body, size 4 with black radial imprint “NVR/ABL” on cap. Tasigna 200 mg hard capsules White to yellowish powder in light yellow opaque hard gelatin capsules, size 0 with red axial imprint “NVR/TKI”. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Tasigna is indicated for the treatment of: - adult and paediatric patients with newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome positive chronic myelogenous leukaemia (CML) in the chronic phase, - adult patients with chronic phase and accelerated phase Philadelphia chromosome positive CML with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy including imatinib. Efficacy data in patients with CML in blast crisis are not available, - paediatric patients with chronic phase Philadelphia chromosome positive CML with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy including imatinib. 2 4.2 Posology and method of administration Therapy should be initiated by a physician experienced in the diagnosis and the treatment of patients with CML. -

The Effects of Combination Treatments on Drug Resistance in Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia: an Evaluation of the Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Axitinib and Asciminib H

Lindström and Friedman BMC Cancer (2020) 20:397 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-06782-9 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The effects of combination treatments on drug resistance in chronic myeloid leukaemia: an evaluation of the tyrosine kinase inhibitors axitinib and asciminib H. Jonathan G. Lindström and Ran Friedman* Abstract Background: Chronic myeloid leukaemia is in principle a treatable malignancy but drug resistance is lowering survival. Recent drug discoveries have opened up new options for drug combinations, which is a concept used in other areas for preventing drug resistance. Two of these are (I) Axitinib, which inhibits the T315I mutation of BCR-ABL1, a main source of drug resistance, and (II) Asciminib, which has been developed as an allosteric BCR-ABL1 inhibitor, targeting an entirely different binding site, and as such does not compete for binding with other drugs. These drugs offer new treatment options. Methods: We measured the proliferation of KCL-22 cells exposed to imatinib–dasatinib, imatinib–asciminib and dasatinib–asciminib combinations and calculated combination index graphs for each case. Moreover, using the median–effect equation we calculated how much axitinib can reduce the growth advantage of T315I mutant clones in combination with available drugs. In addition, we calculated how much the total drug burden could be reduced by combinations using asciminib and other drugs, and evaluated which mutations such combinations might be sensitive to. Results: Asciminib had synergistic interactions with imatinib or dasatinib in KCL-22 cells at high degrees of inhibition. Interestingly, some antagonism between asciminib and the other drugs was present at lower degrees on inhibition. -

Bridging from Preclinical to Clinical Studies for Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Based on Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics and Toxicokinetics/Toxicodynamics

Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 26 (6): 612620 (2011). Copyright © 2011 by the Japanese Society for the Study of Xenobiotics (JSSX) Regular Article Bridging from Preclinical to Clinical Studies for Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Based on Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics and Toxicokinetics/Toxicodynamics Azusa HOSHINO-YOSHINO1,2,MotohiroKATO2,KohnosukeNAKANO2, Masaki ISHIGAI2,ToshiyukiKUDO1 and Kiyomi ITO1,* 1Research Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Musashino University, Tokyo, Japan 2Pre-clinical Research Department, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Kanagawa, Japan Full text of this paper is available at http://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/browse/dmpk Summary: The purpose of this study was to provide a pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics and toxi- cokinetics/toxicodynamics bridging of kinase inhibitors by identifying the relationship between their clinical and preclinical (rat, dog, and monkey) data on exposure and efficacy/toxicity. For the eight kinase inhibitors approved in Japan (imatinib, gefitinib, erlotinib, sorafenib, sunitinib, nilotinib, dasatinib, and lapatinib), the human unbound area under the concentration-time curve at steady state (AUCss,u) at the clinical dose correlated well with animal AUCss,u at the no-observed-adverse-effect level (NOAEL) or maximum tolerated dose (MTD). The best correlation was observed for rat AUCss,u at the MTD (p < 0.001). Emax model analysis was performed using the efficacy of each drug in xenograft mice, and the efficacy at the human AUC of the clinical dose was evaluated. The predicted efficacy at the human AUC of the clinical dose varied from far below Emax to around Emax even in the tumor for which use of the drugs had been accepted. These results suggest that rat AUCss,u attheMTD,butnottheefficacy in xenograft mice, may be a useful parameter to estimate the human clinical dose of kinase inhibitors, which seems to be currently determined by toxicity rather than efficacy. -

Thyrosin Kinase Inhibitors: Nilotinib F

Hematology Meeting Reports 2008;2(5):22-26 SESSION II F. Castagnetti Thyrosin kinase inhibitors: nilotinib F. Palandri G. Gugliotta A. Poerio M. Amabile S. Soverini G. Martinelli M. Baccarani G. Rosti Nilotinib is an aminopyrimidine The only BCR-ABL mutant that derivative that inhibits the tyro- was not inhibited by nilotinib was Department of Hematology, St. Orsola University Hospital sine kinase activity of the T315I. Bologna, Italy chimeric protein BCR-ABL. The unregulated activity of the ABL tyrosine kinase in the BCR-ABL Pharmacokinetic profile protein causes CML, and inhibi- tion of tyrosine kinase activity is The extent of nilotinib absorp- key to the treatment of the disor- tion following oral administration der. Nilotinib acts via competitive was estimated to be approximate- inhibition at the binding site of the ly 30%. The bioavailability of BCR-ABL protein in a similar nilotinib was increased when manner to imatinib, although nilo- given with a meal. Compared to tinib has a higher binding affinity the fasted state, the systemic and selectivity for the ABL exposure (AUC) in the fed state kinase. Once bound to the ATP- increased by 15% (drug adminis- binding site, nilotinib inhibits tered 2 hours after a light meal), tyrosine phosphorylation of pro- 29% (30 minutes after a light teins involved in BCR-ABL- meal), or 82% (30 minutes after a mediated intracellular signal high fat meal), and the Cmax transduction. increased by 33% (2 hours after a The inhibitory activity of nilo- light meal), 55% (30 minutes tinib in CML cell is markedly after a light meal), or 112% (30 higher than that of imatinib. -

Novel Approaches for Efficient Delivery of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

J Pharm Pharm Sci (www.cspsCanada.org) 22, 37 - 48, 2019 Novel Approaches for Efficient Delivery of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Zahra moradpour1, Leila Barghi2 1Department of Pharmaceutical biotechnology and 2Department of Pharmaceutics, School of Pharmacy, Urmia University of medical sciences, Urmia, Iran. Received, September 15, 2018; Revised October 25, 2018; Accepted, January 7, 2019; Published, January 9, 2018. ABSTRACT - Epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs) have potential to be considered as therapeutic target for cancer treatment especially in cancer patients with overexpression of EGFR. Cetuximab as a first monoclonal antibody and Imatinib as the first small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor (SMTKI) were approved by FDA in 1998 and 2001. About 28 SMTKIs have been approved until 2015 and a large number of compound with kinase inhibitory activity are at the different phases of clinical trials. Although Kinase inhibitors target specific intracellular pathways, their tissue or cellular distribution are not specific. So treatment with these drugs causes serious dose dependent side effects. Targeted delivery of kinase inhibitors via dendrimers, polymeric nanoparticles, magnetic nanoparticles and lipid based delivery systems such as liposomes, solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) can lead to reduction of side effects and improving therapeutic efficacy of the drugs in the target organs. Furthermore formulation of these drugs is challenged by their physicochemical properties such as solubility and dissolution rate. The main approaches in order to increase dissolution rate, are particle size reduction, self-emulsification, cyclodextrin complexation, crystal modification and amorphous solid dispersion. Synergistic therapeutic effect, decreased side effects and drug resistant, reduced cost and increased patient compliance are the advantages associated with using combination therapy especially in the treatment of cancer. -

Effects of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (Nilotinib) on Male Mice Infertility

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine ISSN 2515-8260 Volume 07, Issue 03, 2020 Effects Of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (Nilotinib) On Male Mice Infertility Khaleed J Khaleel1, Mohanad Mahdi Al-Hindawi2, Lieth Husein alwan3, Alaa Abbas Fadhel4 1,2,3Iraqi Center for cancer and medical genetics research// Al-Mustansiriyah University, Iraq.. 4Al- Mussaib Technical College / Al-Furat Al-Awsat Technical University, 51009, Babylon, Iraq. E-mail [email protected] ABSTRACT Nilotinib (TasignaTM) a tyrosine kinase inhibitor is used in the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia and other tumor entities, this study aims to investigate nilotinib effects on fertility in male albino mice three groups each with 7 male albino mice selected, one control group, and two groups administered with 80mg/kg and 120mg/kg respectively for 3 months and serum levels of testosterone, FSH, and LH were measured by ELISA kits and statistically analyzed. Histological sections from testes prepared and stained with H&E stain and evaluated histopathologically. Statistically significant reduction in the mean of serum testosterone and FSH were seen in treated groups compared with the control group with no significant differences regarding LH concentration; variable histological changes noted in comparison with the control group ranging from mild changes in most cases with more severe atrophic changes in 1 case from the group(2) and 2 cases in a group (3).Our results showed statistically significant changes in testosterone and FSH levels in mice administered with nilotinib with variable deleterious histopathological changes 1. INTRODUCTION Nilotinib is an orally administered aminopyrimidine-derivative inhibitor of BCR-ABL kinase described in 2005 by Weisberg E. -

Sorafenib Inhibits the Imatinib-Resistant KIT Gatekeeper

Cancer Therapy: Preclinical Sorafenib Inhibits the Imatinib-Resistant KIT T670I Gatekeeper Mutation in Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor Tianhua Guo,1Narasimhan P. Agaram,1Grace C. Wong,1Glory Hom,1David D’Adamo,2 Robert G. Maki,2 Gary K. Schwartz,2 Darren Veach,5 Bayard D. Clarkson,5 Samuel Singer,3 Ronald P. DeMatteo,3 Peter Besmer,4 and Cristina R. Antonescu1,4 Abstract Purpose: Resistance is commonly acquired in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor who are treated with imatinibmesylate, often due to the development of secondary muta- tions in the KIT kinase domain. We sought to investigate the efficacy of second-line tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as sorafenib, dasatinib, and nilotinib, against the commonly observed imatinib-resistant KIT mutations (KIT V654A,KITT670I,KITD820Y,andKIT N822K) expressed in the Ba/F3 cellular system. Experimental Design: In vitro drug screening of stable Ba/F3 KIT mutants recapitulating the genotype of imatinib-resistant patients harboring primary and secondary KIT mutations was investigated. Comparison was made to imatinib-sensitive Ba/F3 KIT mutant cells as well as Ba/F3 cells expressing only secondary KIT mutations.The efficacy of drug treatment was evalu- ated by proliferation and apoptosis assays, in addition to biochemical inhibition of KITactivation. Results: Sorafenibwas potent against all imatinib-resistant Ba/F3 KIT double mutants tested, including the gatekeeper secondary mutation KITWK557-8del/T670I, which was resistant to other kinase inhibitors. Although all three drugs tested decreased cell proliferation and inhibited KIT activation against exon 13 (KITV560del/V654A) and exon 17 (KITV559D/D820Y) double mutants, nilotinibdid so at lower concentrations. Conclusions: Our results emphasize the need for tailored salvage therapy in imatinib-refractory gastrointestinal stromal tumors according to individual molecular mechanisms of resistance. -

Your Pharmacy Benefits Welcome to Your Pharmacy Plan

Your Pharmacy Benefits Welcome to Your Pharmacy Plan OptumRx manages your pharmacy benefits for your health plan sponsor. We look forward to helping you make informed decisions about medicines for you and your family. Please review this information to better understand your pharmacy benefit plan. Using Your Member ID Card You can use your pharmacy benefit ID card at any pharmacy participating in your plan’s pharmacy network. Show your ID card each time you fill a prescription at a network pharmacy. They will enter your card information and automatically file it with OptumRx. Your pharmacy will then collect your share of the payment. Your Pharmacy Network Your plan’s pharmacy network includes more than 67,000 independent and chain retail pharmacies nationwide. To find a network pharmacy near you, use the Locate a Pharmacy tool at www.optumrx.com. Or call Customer Service at 1-877-559-2955. Using Non -Network Pharmacies If you do not show the pharmacy your member ID card, or you fill a prescription at a non-network pharmacy, you must pay 100 percent of the pharmacy’s price for the drug. If the drug is covered by your plan, you can be reimbursed. To be reimbursed for eligible prescriptions, simply fill out and send a Direct Member Reimbursement Form with the pharmacy receipt(s) to OptumRx. Reimbursement amounts are based on contracted pharmacy rates minus your copayment or coinsurance. For a copy of the form, go to www.optumrx.com. Or call the Customer Service number above. The number is also on the back of your ID card. -

Effects of Imatinib, Nilotinib, Dasatinib on VEGF and VEGFR-1 Levels in Patients with Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia

Eur J Gen Med 2016;13(2):111-115 Original Article DOI : 10.15197/ejgm.1527 Effects of Imatinib, Nilotinib, Dasatinib on VEGF and VEGFR-1 Levels in Patients with Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia Rahşan Yıldırım1, Gülden Sincan1, Çiğdem Pala2, Musa Düdükcü3, Leylagül Kaynar2, Selin Merih Urlu4, İlhami Kiki1, Fuat Erdem1, Mustafa Çetin2, Mehmet Gündoğdu1, Ömer Topdağı4 Kronik Myeloid Lösemili Hastalarda İmatinib, Nilotinib, Dasatinib’in VEGF ve VEGFR-1 Düzeyleri Üzerine Etkileri ABSTRACT ÖZET Objective: Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a protein that Amaç: Vasküler endotelyal büyüme faktörü (VEGF), VEGF reseptörl- binding to VEGF receptors 1 (VEGFR-1) and accelerates angiogenesis. erine bağlanarak angiogenezi hızlandıran bir proteindir. Anjiogenez ile The relationship between angiogenesis and progression of tumors were tümörlerin progresyonu arasındaki ilişki hem solid hemde hematolojik observed in both solid and hematologic cancers. Monoclonal antibodies kanserlerde saptanmıştır. Anjiogenez inhibisyonu yapan monoklonal capable of inhibiting angiogenesis, tyrosine kinase inhibitors use for hae- antikorlardan tirozin kinaz inhibitörleri tedavide kullanılabilir. Bu matological cancer treatment. In this study; we investigated the effects çalışmada amaç kronik faz Kronik Myeloid lösemi (KML) hastalarında of Imatinib mesylate (STI-571; Gleevec), Nilotinib (AMN107; Tasigna) and İmatinib mesylate (STI-571; Gleevec), Nilotinib (AMN107; Tasigna) and Dasatinib (BMS-354825; Sprycell) on serum levels of VEGF and VEGFR-1, in dasatinib’in (BMS-354825; Sprycell) serum VEGF ve VEGF reseptör 1 patients with chronic phase of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Method: (VEGFR-1) düzeyine etkilerini araştırmaktır. Yöntem: 65 kronik faz Serum levels of VEGF and VEGFR-1 were measured in 65 patients with KML hastasında serum VEGF ve VEGFR-1 düzeyi ölçüldü. -

(Ara-C) and Nilotinib (Tasigna) (DATA) in Patients Newly Diagnosed with Acute Myeloid Leukemia and KIT Overexpression

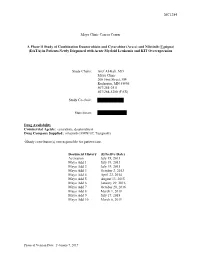

MC1284 Mayo Clinic Cancer Center A Phase II Study of Combination Daunorubicin and Cytarabine (Ara-c) and Nilotinib (Tasigna) (DATA) in Patients Newly Diagnosed with Acute Myeloid Leukemia and KIT Overexpression Study Chairs: Aref Al-Kali, MD Mayo Clinic 200 First Street, SW Rochester, MN 55905 507/284-2511 507/284-5280 (FAX) Study Co-chair: Statistician: Drug Availability Commercial Agents: cytarabine, daunorubicin Drug Company Supplied: nilotinib (AMN107, Tasigna®) √Study contributor(s) not responsible for patient care. Document History (Effective Date) Activation July 19, 2013 Mayo Add 1 July 19, 2013 Mayo Add 2 July 19, 2013 Mayo Add 3 October 2, 2013 Mayo Add 4 April 22, 2014 Mayo Add 5 August 13, 2015 Mayo Add 6 January 29, 2016 Mayo Add 7 October 20, 2016 Mayo Add 8 March 1, 2018 Mayo Add 9 July 17, 2018 Mayo Add 10 March 6, 2019 Protocol Version Date: February 7, 2019 MC1284 3 Mayo Addendum 9 Table of Contents A Phase II Study of Combination Daunorubicin and Cytarabine (Ara-c) and Nilotinib (Tasigna) (DATA) in Patients Newly Diagnosed with Acute Myeloid Leukemia and KIT Overexpression .............................. 1 Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Schema .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 List of Abbreviations ...................................................................................................................................