AB 988 Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwe

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfgh jklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvb nmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwer JASS Training Manual tyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas Please check with the specific organization that you are assigned to and verify these processes. This is dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklz meant to be used as a guide only. x 5/2009 cvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq Latest Update 07/26/2012 wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmrty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw 1 ertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiop asdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjkl Table of Contents Telephone Services ......................................................................................................... 4 i. Answering your phone ......................................................................................... 4 ii. How to “pick” a line ............................................................................................ 4 iii. Transferring Calls ................................................................................................ 4 iv. Transferring directly to voicemail ....................................................................... 4 B. Scheduling Services ............................................................................................... -

Guidelines on Mobile Device Forensics

NIST Special Publication 800-101 Revision 1 Guidelines on Mobile Device Forensics Rick Ayers Sam Brothers Wayne Jansen http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.800-101r1 NIST Special Publication 800-101 Revision 1 Guidelines on Mobile Device Forensics Rick Ayers Software and Systems Division Information Technology Laboratory Sam Brothers U.S. Customs and Border Protection Department of Homeland Security Springfield, VA Wayne Jansen Booz Allen Hamilton McLean, VA http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP. 800-101r1 May 2014 U.S. Department of Commerce Penny Pritzker, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology Patrick D. Gallagher, Under Secretary of Commerce for Standards and Technology and Director Authority This publication has been developed by NIST in accordance with its statutory responsibilities under the Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 (FISMA), 44 U.S.C. § 3541 et seq., Public Law (P.L.) 107-347. NIST is responsible for developing information security standards and guidelines, including minimum requirements for Federal information systems, but such standards and guidelines shall not apply to national security systems without the express approval of appropriate Federal officials exercising policy authority over such systems. This guideline is consistent with the requirements of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Circular A-130, Section 8b(3), Securing Agency Information Systems, as analyzed in Circular A- 130, Appendix IV: Analysis of Key Sections. Supplemental information is provided in Circular A- 130, Appendix III, Security of Federal Automated Information Resources. Nothing in this publication should be taken to contradict the standards and guidelines made mandatory and binding on Federal agencies by the Secretary of Commerce under statutory authority. -

DEFINITY Communications System Generic 2.2 World Class Routing Implementation Copyright 1992 AT&T All Rights Reserved Printed in U.S.A

AT&T 555-105-531 Issue 1 June, 1992 DEFINITY Communications System Generic 2.2 World Class Routing Implementation Copyright 1992 AT&T All Rights Reserved Printed in U.S.A. Notice While reasonable efforts were made to ensure that the information in this document was complete and accurate at the time of printing, AT&T can assume no responsibility for any errors. Changes and corrections to the information contained in this document may be incorporated into future reissues. Your Responsibility for Your System's Security You are responsible for the security of your system. AT&T does not warrant that this product is immune from or will prevent unauthorized use of common-carrier telecommunication services or facilities accessed through or connected to it. AT&T will not be responsible for any charges that result from such unauthorized use. Product administration to prevent unauthorized use is your responsibility and your system administrator should read all documents provided with this product to fully understand the features available that may reduce your risk of incurring charges. Trademarks CALLVISOR is a trademark of AT&T. In this document, CallVisor ASAI Gateway is often abbreviated to ASAI Gateway or ASAI. DIMENSION is a registered trademark of AT&T. ESS is a trademark of AT&T. 5ESS is a registered trademark of AT&T. MEGACOM is a registered service mark of AT&T. DEFINITY is a registered trademark of AT&T. In this document, DEFINITY Communications System Generic 2 is often abbreviated to DEFINITY Generic 2, Generic 2, or G2. Ordering Information The ordering number for this document is 555-105-531. -

RECEIVED DOCKET FILE Copy ORIGINAL

RECEIVED DOCKET FILE COpy ORIGINAL OCT 1 3 ZOOO FCC MAIL ROOM Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Implementation of911 Act ) WT Docket No. 00-110 ) The Use ofNIl Codes and Other ) CC Docket No._92-105J Abbreviated Dialing Arrangements ) ) COMMENTS OF THE WIRELESS CONSUMERS ALLIANCE, INC. AND PETITION FOR FURTHER RULEMAKING Wireless Consumers Alliance, Inc. ("WCA") submits these comments with respect to the Commission's Notice ofProposed Rulemakint in the above caption matters and petitions the Commission to include one other core issue in its deliberations. These comments are directed toward the NPRMin Docket No. 92-105.2 1 In the Matter ofImplementation of911 Act (WTDocket No. 00-110) and The Use of NIl Codes and Other AbbreviatedDialing Arrangements (CC Docket No. 92-105), Fourth Report and Order and Third Notice ofProposed Rulemaking (CC Docket No. 92-105) ("NPRM") and Notice ofProposed Rulemaking (WT Docket No. 00-110). 2 Parties were directed to "identify comments for each Docket Number." (§ Y.E.). We support the Commission's recommendations in Docket No. 00-110 however, we think that the objective ofcreating a "seamless, ubiquitous, reliable wireless telecommunications networks"will not be accomplished with negotiations with private carriers who have no incentive to cooperate. There are several current examples ofwireless carrier non-cooperation in Docket 94-102, e.g. the King County Letter and the Texas 911 Group. The reality is the nation's wireless network is neither seamless, ubiquitous or reliable and will not become so by continuing to depend on the voluntary actions ofwireless carriers or market forces. -

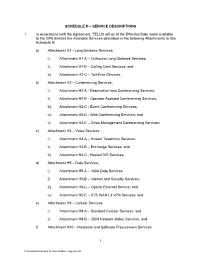

SCHEDULE H – SERVICE DESCRIPTIONS 1. in Accordance with the Agreement, TELUS Will As of the Effective Date Make Available to T

SCHEDULE H – SERVICE DESCRIPTIONS 1. In accordance with the Agreement, TELUS will as of the Effective Date make available to the GPS Entities the Available Services described in the following Attachments to this Schedule H: a) Attachment H1 - Long Distance Services; i) Attachment H1-A – Outbound Long Distance Services; ii) Attachment H1-B – Calling Card Services; and iii) Attachment H1-C – Toll-Free Services; b) Attachment H2 – Conferencing Services; i) Attachment H2-A - Reservation-less Conferencing Services; ii) Attachment H2-B - Operator Assisted Conferencing Services; iii) Attachment H2-C - Event Conferencing Services; iv) Attachment H2-D - Web Conferencing Services; and v) Attachment H2-E – Crisis Management Conferencing Services; c) Attachment H3 – Voice Services; i) Attachment H3-A – Hosted Telephony Services; ii) Attachment H3-B – Exchange Services; and iii) Attachment H3-C - Hosted IVR Services; d) Attachment H5 – Data Services; i) Attachment H5-A – Initial Data Services ii) Attachment H5-B – Internet and Security Services; iii) Attachment H5-C – Optical Ethernet Service; and iv) Attachment H5-E – STS WAN L3 VPN Services; and e) Attachment H9 – Cellular Services; i) Attachment H9-A – Standard Cellular Services; and ii) Attachment H9-B – iDEN Network (Mike) Services; and f) Attachment H10 – Hardware and Software Procurement Services. 1 Telecommunications Services Master Agreement 2. TELUS will provide the Available Services described in the Attachments to this Schedule if and when requested by a GPS Entity pursuant to a Service Order or Service Change Order, subject to section 7.4.3 of the main body of this Agreement, in each case entered into in accordance with the terms of this Agreement, for the applicable Fees as set out in the Price Book and/or, subject to section 1.3.3 of the main body of this Agreement, the applicable Service Order or Service Change Order and as such Available Services are delivered in accordance with the terms of the Agreement including, without limitation, the Service Levels for such Services. -

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce

U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE March 20, 2018 TO: Members, Subcommittee on Communications and Technology FROM: Committee Majority Staff RE: Hearing entitled “Legislative Hearing on Four Telecommunications Bills.” I. INTRODUCTION The Subcommittee on Communications and Technology will hold a hearing on Thursday, March 22, 2018, at 10:15 a.m. in 2322 Rayburn House Office Building. The hearing is entitled “Legislative Hearing on Four Telecommunications Bills.” II. WITNESSES • Tim Donovan, Senior Vice President, Legislative Affairs, Competitive Carriers Association; • David Donovan, President and Executive Director, New York State Broadcasters Association, Inc.; • Bob Gessner; President; MCTV; • Dr. Christine Moutier; Chief Medical Officer; American Foundation for Suicide Prevention; and • Sarah Morris; Director of Open Internet Policy; Open Technology Institute. III. BACKGROUND AND SUMMARY OF LEGISLATION On Thursday, the Subcommittee will review four bills: (1) H.R. 3787, which relaxes the regulatory burdens, costs, and procedural obligations of small entities before the Federal Communications Commission (FCC); (2) H.R. 2903, which directs the FCC to promulgate rules that establish a national standard for determining whether rural areas have reasonably comparable wireless and broadband services to urban areas; (3) H.R. 2345, which directs the FCC, in consultation with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), to study and report on the feasibility of designating an N11 dialing code to be used for a national suicide prevention and mental health crisis hotline system; and (4) a discussion draft which would give the FCC more tools to combat illegal pirate operations and protect the public benefits provided by legitimately licensed broadcasters. -

Sierra Telephone Company, Inc. SCHEDULE CAL

Sierra Telephone Company, Inc. SCHEDULE CAL. P.U.C. NO. A9 Oakhurst, California Original Check Sheet A U-1016-C LIST OF EFFECTIVE SHEETS Sheets listed below are effective as of the date shown on each sheet. Revision Number Sheet Original CS A Original 1 Original 2 Original 3 Original 4 Original 5 Original 6 Original 7 Original 8 Original 9 Original 10 Original 11 Original 12 Original 13 (To be inserted by utility) Issued by (To be inserted by Cal. P.U.C.) Advice Letter No. 365 Harry H. Baker Date Filed May 29, 2008 NAME Effective August 4, 2008 Decision No. 07-01-024 President TITLE Resolution No. Sierra Telephone Company, Inc. SCHEDULE CAL. P.U.C. NO. A9 Oakhurst, California Original Sheet 1 U-1016-C A9. PUBLIC ACCESS LINE SERVICE 9.1 GENERAL INFORMATION 9.1.1 APPLICABILITY Applicable to Public Access Line (PAL) Service, which is offered for the purpose of providing access line service to a Customer-Owned Pay Telephone (COPT). 9.1.2 TERRITORY Within the exchange areas of all exchanges as said areas are defined on maps filed as part of the tariff schedules. 9.2 RATES MONTHLY RATE A. Each Public Access Line (PAL), Rate applicable to business flat rate service primary service, as listed in Schedule Cal. P.U.C. No. A3, Individual and Party Line Service B. Payphone Service Providers Enforcement (PSPE) Program Surcharge, each PAL * C. Public Policy Payphone Surcharge, each PAL * D. Optional Features and Functions Central Office Implemented Rate applicable to Coin Coin Line Features, includes Supervision Additive as Answer Supervision and filed in National Exchange Coin Collection and Return Carrier’s Association (NECA) Tariff F.C.C. -

8X8, Inc. 2020 Annual Report

Annual Report Fiscal 2020 Dear 8x8 Shareholders, I am writing to you about our company’s achievements and experiences over the last year, but the starting point has to be that, in early 2020, the world began to truly embrace what we at 8x8 have been planning for and enabling over the last 30+ years. Since the invention of the telegraph revolutionized long-distance communication in the 1830s and 1840s, human beings have applied their creativity to improving peoples’ ability to interact with each other without being in the same physical location. We recognized that advancing digital capabilities have the potential to enable great leaps forward in this progression. Just as importantly, we have worked to turn this potential into a real-world, seamless, affordable, dependable, and valuable set of services. The COVID-19 pandemic has drawn incredible attention and new urgency to these advances. The world’s ever-growing population means we simply must plan on the risks of pathogens spreading rapidly and globally more regularly. This risk puts a premium on every businesses’ ability to function without in-person events that increasingly put lives at risk. Our unified, cloud-based voice, video, chat, contact-center, and enterprise-class API solutions enable work-from- anywhere and work-from-any device. We are therefore pleased, both as global citizens and as executives of 8x8, that the services we provide are at the top of CIOs buying agendas. These purchases are predicted to increase demand in our sector by double-digit growth annually.1 We accomplished a lot in our fiscal 2020. -

UX5000 Feature Guide

Multibutton Terminal Feature Handbook 0913400 Rev 1, June 2008 Printed in U.S.A. This manual has been developed by NEC Unified Solutions, Inc. It is intended for the use of its customers and service personnel, and should be read in its entirety before attempting to install or program the system. Any comments or suggestions for improving this manual would be appreciated. Forward your remarks to: NEC Unified Solutions, Inc. 4 Forest Parkway Shelton, CT 06484 necunifiedsolutions.com Nothing contained in this manual shall be deemed to be, and this manual does not constitute, a warranty of, or representation with respect to, any of the equipment covered. This manual is subject to change without notice and NEC Unified Solutions, Inc. has no obligation to provide any updates or corrections to this manual. Further, NEC Unified Solutions, Inc. also reserves the right, without prior notice, to make changes in equipment design or components as it deems appropriate. No representation is made that this manual is complete or accurate in all respects and NEC Unified Solutions, Inc. shall not be liable for any errors or omissions. In no event shall NEC Unified Solutions, Inc. be liable for any incidental or consequential damages in connection with the use of this manual. This document contains proprietary information that is protected by copyright. All rights are reserved. No part of this document may be photocopied or reproduced without prior written consent of NEC Unified Solutions, Inc. ©2008 by NEC Unified Solutions, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Printed in U.S.A. Table of Contents Table of Contents Using Your Terminal . -

Federal Communications Commission FCC 19-76 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 in the Matter Of

Federal Communications Commission FCC 19-76 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Implementing Kari’s Law and Section 506 of RAY ) PS Docket No. 18-261 BAUM’S Act ) ) Inquiry Concerning 911 Access, Routing, and ) PS Docket No. 17-239 Location in Enterprise Communications Systems ) ) Amending the Definition of Interconnected VoIP ) GN Docket No. 11-117 Service in Section 9.3 of the Commission’s Rules ) REPORT AND ORDER Adopted: August 1, 2019 Released: August 2, 2019 By the Commission: Chairman Pai and Commissioners O’Rielly and Carr issuing separate statements; Commissioners Rosenworcel and Starks approving in part, dissenting in part, and issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 1 II. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................... 3 III. DISCUSSION ...................................................................................................................................... 14 A. Direct Dialing and Notification for MLTS .................................................................................... 14 1. Direct Dialing .......................................................................................................................... 15 2. Notification ............................................................................................................................. -

CODE of COLORADO REGULATIONS 4 CCR 723-2 Public Utilities Commission

DEPARTMENT OF REGULATORY AGENCIES Public Utilities Commission RULES REGULATING TELECOMMUNICATIONS SERVICES AND PROVIDERS OF TELECOMMUNICATIONS SERVICES 4 CCR 723-2 [Editor’s Notes follow the text of the rules at the end of this CCR Document.] _________________________________________________________________________ BASIS, PURPOSE, AND STATUTORY AUTHORITY The basis and purpose of these rules is generally to implement, administer and enforce the telecommunications provisions of Title 40 of the Colorado Revised Statutes; and regulate telecommunications proceedings and regulatory activities before the Commission. These rules address a wide variety of subject areas. Therefore, specific statements of Basis, Purpose, and Statutory Authority are found at the beginning of each subchapter of these rules. The statutory authority for the promulgation of these rules is found at §§ 29-11-106(3); 38-5.5-101; 39-32- 104; 40-2-108; 40-3-101; 40-3-102; 40-3-103; 40-3-107; 40-3-110; 40-3.4-106; 40-4-101; 40-7-113.5; 40- 7-116.5; 40-15-101; 40-15-108(2); 40-15-109(3); 40-15-201; 40-15-203.5; 40-15-208(2)(a); 40-15-301; 40-15-302(1)(a) and (2); 40-15-302.5; 40-15-305; 40-15-404; 40-15-502(1), (3)(a), and (5)(b); 40-15-503; 40-17-103(2) and (3), C.R.S. GENERAL PROVISIONS 2000. Scope and Applicability. Rules 2000 through 2099 are rules of general applicability to be applied consistent with Commission jurisdiction and rules 2100 through 2999. More specific applicability provisions are found in the various subchapters of this Part 2. -

Safety and Precautions Accordance with the Manufacturer's Instructions

is a risk of explosion if the battery is replaced by an incorrect type. Disposal of used battery must be in Safety And Precautions accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. • Using any battery pack, AC adapter or vehicle power Emergency services adapter (option) not specified by the manufacturer for To make an emergency call in any country: use with this phone creates a potential safety hazard. ☛ Press 112, . • The earpiece may become warm during normal use and the unit itself may become warm during charging. Ask the operator for the service which you require: Police, • Use a damp or anti-static cloth to clean the phone. Do Ambulance, Fire Brigade, Coastguard or Mountain Rescue NOT use a dry cloth or electrostatically charged cloth. Services. Give your location and, if possible, remain Do not use chemical or abrasive cleaners as these stationary to maintain phone contact. could damage the casing. The 112 emergency number service is available on every • Recycling: the cardboard packaging supplied with this digital network service. The number 999 is an alternative phone is ideal for recycling. emergency number for UK only, and can only be used • Do not leave the battery pack empty or disconnected for with a valid SIM card. a long time, otherwise certain data may be initialised. 2 Due to the nature of the mobile network system, • Your phone contains metal which may cause itching, the success of emergency calls cannot be rashes or eczema depending on your constitution or guaranteed. physical condition. 2 For customized local emergency numbers, • Take care not to put your phone in the back pocket of please check with your local units for the your trousers or skirt and then sit on it.