Known Plaintext Attack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Cryptography

Basic cryptography • How cryptography works... • Symmetric cryptography... • Public key cryptography... • Online Resources... • Printed Resources... I VP R 1 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz How cryptography works • Plaintext • Ciphertext • Cryptographic algorithm • Key Decryption Key Algorithm Plaintext Ciphertext Encryption I VP R 2 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Simple cryptosystem ... ! ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ! DEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABC • Caesar Cipher • Simple substitution cipher • ROT-13 • rotate by half the alphabet • A => N B => O I VP R 3 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Keys cryptosystems … • keys and keyspace ... • secret-key and public-key ... • key management ... • strength of key systems ... I VP R 4 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Keys and keyspace … • ROT: key is N • Brute force: 25 values of N • IDEA (international data encryption algorithm) in PGP: 2128 numeric keys • 1 billion keys / sec ==> >10,781,000,000,000,000,000,000 years I VP R 5 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Symmetric cryptography • DES • Triple DES, DESX, GDES, RDES • RC2, RC4, RC5 • IDEA Key • Blowfish Plaintext Encryption Ciphertext Decryption Plaintext Sender Recipient I VP R 6 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz DES • Data Encryption Standard • US NIST (‘70s) • 56-bit key • Good then • Not enough now (cracked June 1997) • Discrete blocks of 64 bits • Often w/ CBC (cipherblock chaining) • Each blocks encr. depends on contents of previous => detect missing block I VP R 7 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Triple DES, DESX, -

Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard

Lecture 3: Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard Lecture Notes on “Computer and Network Security” by Avi Kak ([email protected]) January 26, 2021 3:43pm ©2021 Avinash Kak, Purdue University Goals: To introduce the notion of a block cipher in the modern context. To talk about the infeasibility of ideal block ciphers To introduce the notion of the Feistel Cipher Structure To go over DES, the Data Encryption Standard To illustrate important DES steps with Python and Perl code CONTENTS Section Title Page 3.1 Ideal Block Cipher 3 3.1.1 Size of the Encryption Key for the Ideal Block Cipher 6 3.2 The Feistel Structure for Block Ciphers 7 3.2.1 Mathematical Description of Each Round in the 10 Feistel Structure 3.2.2 Decryption in Ciphers Based on the Feistel Structure 12 3.3 DES: The Data Encryption Standard 16 3.3.1 One Round of Processing in DES 18 3.3.2 The S-Box for the Substitution Step in Each Round 22 3.3.3 The Substitution Tables 26 3.3.4 The P-Box Permutation in the Feistel Function 33 3.3.5 The DES Key Schedule: Generating the Round Keys 35 3.3.6 Initial Permutation of the Encryption Key 38 3.3.7 Contraction-Permutation that Generates the 48-Bit 42 Round Key from the 56-Bit Key 3.4 What Makes DES a Strong Cipher (to the 46 Extent It is a Strong Cipher) 3.5 Homework Problems 48 2 Computer and Network Security by Avi Kak Lecture 3 Back to TOC 3.1 IDEAL BLOCK CIPHER In a modern block cipher (but still using a classical encryption method), we replace a block of N bits from the plaintext with a block of N bits from the ciphertext. -

1 Perfect Secrecy of the One-Time Pad

1 Perfect secrecy of the one-time pad In this section, we make more a more precise analysis of the security of the one-time pad. First, we need to define conditional probability. Let’s consider an example. We know that if it rains Saturday, then there is a reasonable chance that it will rain on Sunday. To make this more precise, we want to compute the probability that it rains on Sunday, given that it rains on Saturday. So we restrict our attention to only those situations where it rains on Saturday and count how often this happens over several years. Then we count how often it rains on both Saturday and Sunday. The ratio gives an estimate of the desired probability. If we call A the event that it rains on Saturday and B the event that it rains on Sunday, then the intersection A ∩ B is when it rains on both days. The conditional probability of A given B is defined to be P (A ∩ B) P (B | A)= , P (A) where P (A) denotes the probability of the event A. This formula can be used to define the conditional probability of one event given another for any two events A and B that have probabilities (we implicitly assume throughout this discussion that any probability that occurs in a denominator has nonzero probability). Events A and B are independent if P (A ∩ B)= P (A) P (B). For example, if Alice flips a fair coin, let A be the event that the coin ends up Heads. If Bob rolls a fair six-sided die, let B be the event that he rolls a 3. -

Related-Key Cryptanalysis of 3-WAY, Biham-DES,CAST, DES-X, Newdes, RC2, and TEA

Related-Key Cryptanalysis of 3-WAY, Biham-DES,CAST, DES-X, NewDES, RC2, and TEA John Kelsey Bruce Schneier David Wagner Counterpane Systems U.C. Berkeley kelsey,schneier @counterpane.com [email protected] f g Abstract. We present new related-key attacks on the block ciphers 3- WAY, Biham-DES, CAST, DES-X, NewDES, RC2, and TEA. Differen- tial related-key attacks allow both keys and plaintexts to be chosen with specific differences [KSW96]. Our attacks build on the original work, showing how to adapt the general attack to deal with the difficulties of the individual algorithms. We also give specific design principles to protect against these attacks. 1 Introduction Related-key cryptanalysis assumes that the attacker learns the encryption of certain plaintexts not only under the original (unknown) key K, but also under some derived keys K0 = f(K). In a chosen-related-key attack, the attacker specifies how the key is to be changed; known-related-key attacks are those where the key difference is known, but cannot be chosen by the attacker. We emphasize that the attacker knows or chooses the relationship between keys, not the actual key values. These techniques have been developed in [Knu93b, Bih94, KSW96]. Related-key cryptanalysis is a practical attack on key-exchange protocols that do not guarantee key-integrity|an attacker may be able to flip bits in the key without knowing the key|and key-update protocols that update keys using a known function: e.g., K, K + 1, K + 2, etc. Related-key attacks were also used against rotor machines: operators sometimes set rotors incorrectly. -

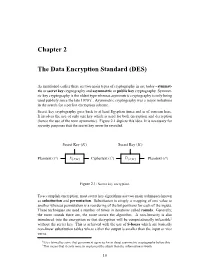

Chapter 2 the Data Encryption Standard (DES)

Chapter 2 The Data Encryption Standard (DES) As mentioned earlier there are two main types of cryptography in use today - symmet- ric or secret key cryptography and asymmetric or public key cryptography. Symmet- ric key cryptography is the oldest type whereas asymmetric cryptography is only being used publicly since the late 1970’s1. Asymmetric cryptography was a major milestone in the search for a perfect encryption scheme. Secret key cryptography goes back to at least Egyptian times and is of concern here. It involves the use of only one key which is used for both encryption and decryption (hence the use of the term symmetric). Figure 2.1 depicts this idea. It is necessary for security purposes that the secret key never be revealed. Secret Key (K) Secret Key (K) ? ? - - - - Plaintext (P ) E{P,K} Ciphertext (C) D{C,K} Plaintext (P ) Figure 2.1: Secret key encryption. To accomplish encryption, most secret key algorithms use two main techniques known as substitution and permutation. Substitution is simply a mapping of one value to another whereas permutation is a reordering of the bit positions for each of the inputs. These techniques are used a number of times in iterations called rounds. Generally, the more rounds there are, the more secure the algorithm. A non-linearity is also introduced into the encryption so that decryption will be computationally infeasible2 without the secret key. This is achieved with the use of S-boxes which are basically non-linear substitution tables where either the output is smaller than the input or vice versa. 1It is claimed by some that government agencies knew about asymmetric cryptography before this. -

Chap 2. Basic Encryption and Decryption

Chap 2. Basic Encryption and Decryption H. Lee Kwang Department of Electrical Engineering & Computer Science, KAIST Objectives • Concepts of encryption • Cryptanalysis: how encryption systems are “broken” 2.1 Terminology and Background • Notations – S: sender – R: receiver – T: transmission medium – O: outsider, interceptor, intruder, attacker, or, adversary • S wants to send a message to R – S entrusts the message to T who will deliver it to R – Possible actions of O • block(interrupt), intercept, modify, fabricate • Chapter 1 2.1.1 Terminology • Encryption and Decryption – encryption: a process of encoding a message so that its meaning is not obvious – decryption: the reverse process • encode(encipher) vs. decode(decipher) – encoding: the process of translating entire words or phrases to other words or phrases – enciphering: translating letters or symbols individually – encryption: the group term that covers both encoding and enciphering 2.1.1 Terminology • Plaintext vs. Ciphertext – P(plaintext): the original form of a message – C(ciphertext): the encrypted form • Basic operations – plaintext to ciphertext: encryption: C = E(P) – ciphertext to plaintext: decryption: P = D(C) – requirement: P = D(E(P)) 2.1.1 Terminology • Encryption with key If the encryption algorithm should fall into the interceptor’s – encryption key: KE – decryption key: K hands, future messages can still D be kept secret because the – C = E(K , P) E interceptor will not know the – P = D(KD, E(KE, P)) key value • Keyless Cipher – a cipher that does not require the -

Block Cipher and Data Encryption Standard (DES)

Block Cipher and Data Encryption Standard (DES) 2021.03.09 Presented by: Mikail Mohammed Salim Professor 박종혁 Cryptography and Information Security 1 Block Cipher and Data Encryption Standard (DES) Contents • What is Block Cipher? • Padding in Block Cipher • Ideal Block Cipher • What is DES? • DES- Key Discarding Process • Des- 16 rounds of Encryption • How secure is DES? 2 Block Cipher and Data Encryption Standard (DES) What is Block Cipher? • An encryption technique that applies an algorithm with parameters to encrypt blocks of text. • Each plaintext block has an equal length of ciphertext block. • Each output block is the same size as the input block, the block being transformed by the key. • Block size range from 64 -128 bits and process the plaintext in blocks of 64 or 128 bits. • Several bits of information is encrypted with each block. Longer messages are encoded by invoking the cipher repeatedly. 3 Block Cipher and Data Encryption Standard (DES) What is Block Cipher? • Each message (p) grouped in blocks is encrypted (enc) using a key (k) into a Ciphertext (c). Therefore, 푐 = 푒푛푐푘(푝) • The recipient requires the same k to decrypt (dec) the p. Therefore, 푝 = 푑푒푐푘(푐) 4 Block Cipher and Data Encryption Standard (DES) Padding in Block Cipher • Block ciphers process blocks of fixed sizes, such as 64 or 128 bits. The length of plaintexts is mostly not a multiple of the block size. • A 150-bit plaintext provides two blocks of 64 bits each with third block of remaining 22 bits. • The last block of bits needs to be padded up with redundant information so that the length of the final block equal to block size of the scheme. -

A Gentle Introduction to Cryptography

A Gentle Introduction Prof. Philip Koopman to Cryptography 18-642 / Fall 2020 “Cryptography [without system integrity] is like investing in an armored car to carry money between a customer living in a cardboard box and a person doing business on a park bench.” – Gene Spafford © 2020 Philip Koopman 1 Cryptography Overview Anti-Patterns for Cryptography Using a home-made cryptographic algorithm Using private key when public key is required Not considering key distribution in design Cryptography terms: Plaintext: the original data Ciphertext: data after a encryption Encryption: converting plaintext to ciphertext Avalanche effect: – Confusion: multiple bits in plaintext are combined to make a ciphertext bit – Diffusion: each bit of plaintext affects many bits of ciphertext – Ideally, ciphertext is random function of plaintext bits © 2020 Philip Koopman 2 Classical Cryptography Simple substitution cipher (Caesar Cipher) “IBM” left shifted 1 becomes “HAL” – 4 or 5 bit key (26 wheel positions) https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caesar- Verschl%C3%BCsselung#/media/File:Ciph erDisk2000.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caesar_cipher Readily broken via frequency analysis Most common letters correspond to E, T, A, O, … https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caesar_cipher Gives secrecy but not explicit integrity © 2020 Philip Koopman 3 WWII Cryptography Complex Subsitution Cipher German “Enigma” machine The “Bombe” broke Enigma Electromechanical sequencing to search for correlations using guessed plaintext – See the movie: “The Imitation Game” -

A Short-Key One-Time Pad Cipher

A short-key one-time pad cipher Uwe Starossek Abstract A process for the secure transmission of data is presented that has to a certain degree the advantages of the one-time pad (OTP) cipher, that is, simplicity, speed, and information- theoretically security, but overcomes its fundamental weakness, the necessity of securely exchanging a key that is as long as the message. For each transmission, a dedicated one-time pad is generated for encrypting and decrypting the plaintext message. This one-time pad is built from a randomly chosen set of basic keys taken from a public library. Because the basic keys can be chosen and used multiple times, the method is called multiple-time pad (MTP) cipher. The information on the choice of basic keys is encoded in a short keyword that is transmitted by secure means. The process is made secure against known-plaintext attack by additional design elements. The process is particularly useful for high-speed transmission of mass data and video or audio streaming. Keywords hybrid cipher; multiple-time pad; random key; secure transmission; mass data; streaming 1 Introduction A cipher is an algorithm for encryption and decryption with the purpose of securely transmitting data. The only information-theoretically secure and potentially unbreakable cipher is the one-time pad (OTP) cipher (U.S. Patent 1 310 719). It is simple to implement. Assuming the plaintext is a series of bits, it works as follows. A fresh OTP consisting of random series of bits that is at least as long as the plaintext is generated as a key. -

Applications of Search Techniques to Cryptanalysis and the Construction of Cipher Components. James David Mclaughlin Submitted F

Applications of search techniques to cryptanalysis and the construction of cipher components. James David McLaughlin Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of York Department of Computer Science September 2012 2 Abstract In this dissertation, we investigate the ways in which search techniques, and in particular metaheuristic search techniques, can be used in cryptology. We address the design of simple cryptographic components (Boolean functions), before moving on to more complex entities (S-boxes). The emphasis then shifts from the construction of cryptographic arte- facts to the related area of cryptanalysis, in which we first derive non-linear approximations to S-boxes more powerful than the existing linear approximations, and then exploit these in cryptanalytic attacks against the ciphers DES and Serpent. Contents 1 Introduction. 11 1.1 The Structure of this Thesis . 12 2 A brief history of cryptography and cryptanalysis. 14 3 Literature review 20 3.1 Information on various types of block cipher, and a brief description of the Data Encryption Standard. 20 3.1.1 Feistel ciphers . 21 3.1.2 Other types of block cipher . 23 3.1.3 Confusion and diffusion . 24 3.2 Linear cryptanalysis. 26 3.2.1 The attack. 27 3.3 Differential cryptanalysis. 35 3.3.1 The attack. 39 3.3.2 Variants of the differential cryptanalytic attack . 44 3.4 Stream ciphers based on linear feedback shift registers . 48 3.5 A brief introduction to metaheuristics . 52 3.5.1 Hill-climbing . 55 3.5.2 Simulated annealing . 57 3.5.3 Memetic algorithms . 58 3.5.4 Ant algorithms . -

Cryptographic Algorithms Outline Outline (2) Definitions Cryptology

Cryptographic Algorithms March 2016 Bart Preneel Outline Cryptographic algorithms • 1. Cryptology: concepts and algorithms – symmetric algorithms for confidentiality – symmetric algorithms for data authentication Prof. Bart Preneel – public-key cryptology COSIC • 2. Cryptology: protocols Bart.Preneel(at)esatDOTkuleuven.be – identification/entity authentication http://homes.esat.kuleuven.be/~preneel – key establishment March 2016 • 3. Public-Key Infrastructure fundamentals © Bart Preneel. All rights reserved Outline (2) Definitions data entities Confidentiality confidentiality encryption anonymity Integrity Availability authentication data authentication identification • 4. Network security protocols – web (SSL/TLS) and Ipsec Authorisation • 5. Post-Snowden cryptography Non-repudiation of origin, receipt Don’t use the • 6. Cryptography best practices word Contract signing authentication without defining Notarisation and Timestamping it 4 Cryptology: basic principles Symmetric cryptology: confidentiality • old cipher systems: AliceEve Bob – transposition, substitution, rotor machines • the opponent and her power CRYP • the Vernam scheme CRYP %^C& %^C& Clear Clear TOB TOB @&^( @&^( text OX OX text • DES and triple-DES •AES • RC4 1 Cryptographic Algorithms March 2016 Bart Preneel Old cipher systems (pre 1900) Cryptanalysis example: TIPGK RERCP JZJZJ WLE GVCTX EREPC WMWMW JYR UJQHL SFSDQ KAKAK XMF HWDUY FSFQD XNXNX KZS • Caesar cipher: shift letters over k positions in VKRIM TGTER LBLBL YNG IXEVZ GTGRE YOYOY LAT the alphabet (k is the secret key) WLSJN UHUFS MCMCM ZOH JYFWA HUHSF ZPZPZ MBU XDTKO VOVGT NDNDN API KZGXB IVITG AQAQA NCV THIS IS THE CAESAR CIPHER YNULP WKWHU OEOEO BQJ LAHYC JWJUH BRBRB ODW WKLV LV WKH FDHVDU FLSKHU ZOVMQ XKXIV PFPFP CRK MBIZD KXKVI CSCSC PEX APWNR YLYJW QGQGQ DSL NCJAE LYLWJ DTDTD QFY BQXOS ZMXKX RHRHR ETM ODKBF MZMXK EUEUE RGZ • Julius Caesar never changed his key (k=3). -

Hardware Security: Present Challenges and Future Directions

HWS: Present challenges and Future directions IC Hardware Analysis Workshop, NTU, Singapore, 20 July 2018 Hardware Security: Present challenges and Future directions Dr Sergei Skorobogatov http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~sps32 email: [email protected] Dept of Computer Science and Technology HWS: Present challenges and Future directions IC Hardware Analysis Workshop, NTU, Singapore, 20 July 2018 Outline • Introduction • History of powerful physical attacks • Knowledge and predictability of attacks • Challenges to hardware engineers • Attacking modern devices • Future directions • Conclusion 2 HWS: Present challenges and Future directions IC Hardware Analysis Workshop, NTU, Singapore, 20 July 2018 Introduction • Senior Research Associate at the University of Cambridge – Hardware Security research (attack technologies) since 1995 – Test microcontrollers, smartcards, FPGAs and SoCs for security – Knowledge: chemistry, electronics, physics (MSc), computers (PhD) – PhD in Hardware Security from the University of Cambridge (2005) • Strong track record of new and “impossible” attack methods – 1996: clock glitching attacks on security in MC68HC05 and MC68HC11 MCUs – 1999: power glitching attacks on security in PIC16F62x/8x and AT90SCxx MCUs – 2002: discovery of optical fault injection attacks shook the industry – 2005: prove of data remanence in EEPROM and Flash memory – 2006: use for combined attacks of fault injection with power analysis – 2009: use of optical emission analysis to complement power analysis – 2010: bumping attacks that can extract AES