Published Version (PDF 651Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 19

Darwin Alice Springs Tennant Creek A Airport Development Group International Airport Airport Airport Annual Report 19 . Highlights 2018–19 We reached a milestone The National Critical Care In October 2018, Alice Springs of 21 years since the three and Trauma Response Centre received the first of four airports were privatised was completed at Darwin charter flights from Tokyo, under the NT Airports International Airport in Nagoya and Osaka, Japan, in banner, celebrating with April 2019, creating a world- more than 10 years. a special airside premiere class, on-airport Emergency screening of the aviation Medical Retrieval Precinct. history film ‘The Sweet Little Note of the Engine.’ Virgin Australia launched a new three-times-weekly We refurbished an seasonal service to Denpasar, underused part of the Bali, in April 2019. Sustainability reporting Darwin terminal into the introduced. Emissions target ‘Green Room’, a pop-up developed and on track to community arts space, have zero net emissions by launching it in August 2018. SilkAir announced an 2030 (scope 1 and 2). increase in weekly services between Darwin and Singapore from July 2019, Ian Kew, CEO, continued marking its seventh year of Runway overlay works as Chairman of the Darwin operations to Darwin with a commenced in Alice Springs Major Business Group and seventh weekly service. at a value of circa Chairman of the Darwin $20 million. Festival. ADG staff and the company contributed $18,000 to two ‘Happy or Not’ instant community causes from our $1.4 million infrastructure customer feedback Workplace Giving initiative. boost at Tennant Creek platforms installed in Alice for improved fencing and Springs and Darwin. -

2017 Cacg Report Community Aviation Consultation Group

2017 CACG REPORT COMMUNITY AVIATION CONSULTATION GROUP Contents Chair Message ........................................................................................................ 1 Alice Springs Airport .............................................................................................. 2 Alice Springs ............................................................................................................. 2 Airport Location ......................................................................................................... 2 Airport Overview ........................................................................................................ 3 Fast Facts ................................................................................................................. 3 Airport Ownership ...................................................................................................... 4 CACG Membership .................................................................................................. 5 CACG Background .................................................................................................. 9 Context ..................................................................................................................... 9 Consultation Group Role ............................................................................................. 9 Operating Model ........................................................................................................ 9 Member Role ........................................................................................................... -

Northern Territory June 2012 Monthly Weather Review Northern Territory June 2012

Monthly Weather Review Northern Territory June 2012 Monthly Weather Review Northern Territory June 2012 The Monthly Weather Review - Northern Territory is produced twelve times each year by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology's Northern Territory Climate Services Centre. It is intended to provide a concise but informative overview of the temperatures, rainfall and significant weather events in Northern Territory for the month. To keep the Monthly Weather Review as timely as possible, much of the information is based on electronic reports. Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of these reports, the results can be considered only preliminary until complete quality control procedures have been carried out. Major discrepancies will be noted in later issues. We are keen to ensure that the Monthly Weather Review is appropriate to the needs of its readers. If you have any comments or suggestions, please do not hesitate to contact us: By mail Northern Territory Climate Services Centre Bureau of Meteorology PO Box 40050 Casuarina NT 0811 AUSTRALIA By telephone (08) 8920 3813 By email [email protected] You may also wish to visit the Bureau's home page, http://www.bom.gov.au. Units of measurement Except where noted, temperature is given in degrees Celsius (°C), rainfall in millimetres (mm), and wind speed in kilometres per hour (km/h). Observation times and periods Each station in Northern Territory makes its main observation for the day at 9 am local time. At this time, the precipitation over the past 24 hours is determined, and maximum and minimum thermometers are also read and reset. -

Minutes Wa & Nt Division Meeting

MINUTES WA & NT DIVISION MEETING Karratha Airport THURSDAY 12 MAY at 1300 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- OPENING AND WELCOME ADDREESS Welcoming address by NT Chair Mr Tom Ganley, acknowledging Mayor, City of Karratha Peter Long and AAA National Chair Mr Guy Thompson. Welcome to all attendees and acknowledge of the local indigenous people by Mayor Peter Long followed by a brief background on the City of Karratha and Karratha Airport. 1. ATTENDEES: Adam Kett City of Karratha Mike Gough WA Police Protection Security Unit Allan Wright City of Karratha Mitchell Cameron Port Hedland International Airport Andrew Shay MSS Security Nat Santagiuliana PHIA Operating Company Pty Ltd Bob Urquhart City of Greater Geraldton Nathan Lammers Boral Asphalt Brett Karran APEX Crisis Management Nathanael Thomas Aerodrome Management Services Brian Joiner City of Karratha Neil Chamberlain Bituminous Products Daniel Smith Airservices Australia Nick Brass SunEdison Darryl Tonkin Kalgoorlie-Boulder Airport Peter Long City of Karratha Dave Batic Alice Springs Airport Rob Scott Downer Eleanor Whiteley PHIA operating Company Rod Evans Broome International Airport Guy Thompson AAA / Perth Airport Rodney Treloar Shire of Esperance Jennifer May City of Busselton Ross Hibbins Vaisala Jenny Kox Learmonth Airport, Shire of Exmouth Ross Loakim Downer Josh Smith City of Karratha Simon Kot City of Karratha Kevin Thomas Aerodrome -

Environmental Tracers in the Beetaloo Basin Aquifer and Groundwater Characterization

LAND AND WATER Environmental Tracers in the Beetaloo Basin Aquifer and groundwater characterization Alec Deslandes, Christoph Gerber, Sebastien Lamontagne, Cornelia Wilske, Axel Suckow November 2019 Cover Photo: Landholder bore with mechanically driven pump and diesel motor – typical setting at landholder sampling sites. ISBN 978‐1‐4863‐1409‐6 (Print) ISBN 978‐1‐4863‐1410‐2 (Online) Citation Deslandes, Alec, Gerber, Christoph, Lamontagne, Sebastien, Wilske, Cornelia, Suckow, Axel (2019): Environmental Tracers in the Beetaloo Basin. Aquifer and groundwater characterization. CSIRO, Australia. Copyright © Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation 2019. To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO. Important disclaimer CSIRO advises that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation. No reliance or actions must therefore be made on that information without seeking prior expert professional, scientific and technical advice. To the extent permitted by law, CSIRO (including its employees and consultants) excludes all liability to any person for any consequences, including but not limited to all losses, damages, costs, expenses and any other compensation, arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in part or in whole) and any information or material contained in it. CSIRO is committed to providing web accessible content wherever possible. If you are having difficulties with accessing this document, please contact [email protected]. -

Issues Paper on Airservices Australia Draft Price Notification

Airservices Australia Response to ACCC - Issues Paper on Airservices Australia Draft Price Notification Submission by Airport Development Group Pty Ltd September 2004 Airservices Australia ACCC Response to Issues Paper Table of Contents 1. ADG CONTACT DETAILS 3 2. BACKGROUND ON ADG 4 3. CONSULTATION PROCESS 6 4. RISK SHARING ARRANGEMENTS 6 5. OPERATING COSTS 7 6. CAPITAL EXPENDITURE 7 7. ASSET BASE 8 8. RATE OF RETURN 8 9. ACTIVITY FORECASTS 9 10. THE STRUCTURE OF PRICES 9 11. ‘BASIN’ APPROACH TO TERMINAL NAVIGATION CHARGES 10 12. TIMING OF PRICE INCREASES 10 13. PRICING ACROSS SERVICES AND USER GROUPS 10 14. IMPACT ON USERS 11 h:\misc\accc response to asa prices sept 04b.doc Page 2 of 11 Airservices Australia ACCC Response to Issues Paper 1. ADG Contact Details Ian Kew Chief Executive Officer Northern Territory Airports Pty Ltd PO Box 40996 CASUARINA NT 0801 Facsimile: (08) 8920 1800 Phone: (08) 8920 1808 Email: [email protected] Alternate Tom Ganley Chief Financial Officer Northern Territory Airports Pty Ltd PO Box 40996 CASUARINA NT 0801 Facsimile: (08) 8920 1800 Phone: (08) 8920 1845 Email: [email protected] h:\misc\accc response to asa prices sept 04b.doc Page 3 of 11 Airservices Australia ACCC Response to Issues Paper 2. Background on ADG Airport Development Group Pty Limited (ADG) owns 100% of Northern Territory Airports Pty Limited, which in turn owns 100% of Darwin International Airport Pty Limited and Alice Springs Airport Pty Limited. These companies are the holders of 50 year leases commencing June 1998 (with free options to renew for a further 49 years) over Darwin International Airport (DIA) and Alice Springs Airport (ASA) respectively. -

Airport Categorisation List

UNCLASSIFIED List of Security Controlled Airport Categorisation September 2018 *Please note that this table will continue to be updated upon new category approvals and gazettal Category Airport Legal Trading Name State Category Operations Other Information Commencement CATEGORY 1 ADELAIDE Adelaide Airport Ltd SA 1 22/12/2011 BRISBANE Brisbane Airport Corporation Limited QLD 1 22/12/2011 CAIRNS Cairns Airport Pty Ltd QLD 1 22/12/2011 CANBERRA Capital Airport Group Pty Ltd ACT 1 22/12/2011 GOLD COAST Gold Coast Airport Pty Ltd QLD 1 22/12/2011 DARWIN Darwin International Airport Pty Limited NT 1 22/12/2011 Australia Pacific Airports (Melbourne) MELBOURNE VIC 1 22/12/2011 Pty. Limited PERTH Perth Airport Pty Ltd WA 1 22/12/2011 SYDNEY Sydney Airport Corporation Limited NSW 1 22/12/2011 CATEGORY 2 BROOME Broome International Airport Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 CHRISTMAS ISLAND Toll Remote Logistics Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 HOBART Hobart International Airport Pty Limited TAS 2 29/02/2012 NORFOLK ISLAND Norfolk Island Regional Council NSW 2 22/12/2011 September 2018 UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED PORT HEDLAND PHIA Operating Company Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 SUNSHINE COAST Sunshine Coast Airport Pty Ltd QLD 2 29/06/2012 TOWNSVILLE AIRPORT Townsville Airport Pty Ltd QLD 2 19/12/2014 CATEGORY 3 ALBURY Albury City Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 ALICE SPRINGS Alice Springs Airport Pty Limited NT 3 11/01/2012 AVALON Avalon Airport Australia Pty Ltd VIC 3 22/12/2011 Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia NT 3 22/12/2011 AYERS ROCK Pty Ltd BALLINA Ballina Shire Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 BRISBANE WEST Brisbane West Wellcamp Airport Pty QLD 3 17/11/2014 WELLCAMP Ltd BUNDABERG Bundaberg Regional Council QLD 3 18/01/2012 CLONCURRY Cloncurry Shire Council QLD 3 29/02/2012 COCOS ISLAND Toll Remote Logistics Pty Ltd WA 3 22/12/2011 COFFS HARBOUR Coffs Harbour City Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 DEVONPORT Tasmanian Ports Corporation Pty. -

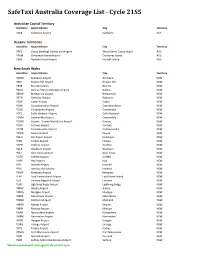

Safetaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5

SafeTaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5 Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER Merimbula -

Financial Report 2019-20

Darwin Alice Springs Tennant Creek A Airport Development Group International Airport Airport Airport Financial Report 20 Highlights 2019–20 Throughout the COVID 19 pandemic ADG has maintained our commitment to and support of: • Our staff and permanent contractors: by providing ongoing employment • The community: by continuing to fund all our sponsorships • The Northern Territory: by continuing to make significant capital investments • Our customers and key stakeholders: by providing relief packages. ADG has commenced a With sustainability a top The cold storage, freight $5 million dollar expansion priority for ADG, and we and training facility at in renewable energy, continue working towards Darwin International increasing solar PV arrays an emissions target to have Airport has been completed, from 7MW to 11MW. zero net emissions (scope 1 signalling new importing and and scope 2) by 2030. exporting opportunities for the Territory. Throughout the pandemic, all three of our airports – A new community Darwin International, Alice partnership began, which From the start of the pandemic Springs and Tennant Creek – sees Larrakia Rangers we provided 31 stakeholder have stayed open. working with Darwin updates to more than International Airport to 780 airport stakeholders maintain the health of the every week. All staff employed across Rapid Creek Reserve in the our airports retained their airport lease area. positions during COVID-19. Major upgrades at Tennant Creek Airport to improve Darwin International Airport fencing and lighting have The Alice Springs Airport purchased two all-electric also been completed. Preliminary Draft 2020 fleet vehicles that utilise Master Plan was released renewable energy generated in May 2020 for public on-airport. -

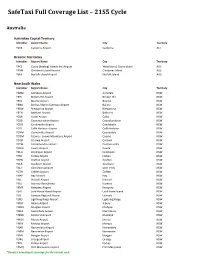

Safetaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Australia Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER -

Draft Tennant Creek Land Use Plan

DRAFT TENNANT CREEK LAND USE PLAN June 2018 E: [email protected] | P: 08 8924 7540 www.planningcommission.nt.gov.au Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), no part of this document may be reproduced without prior written permission from the Northern Territory Government. Enquiries should be made to: Northern Territory Planning Commission GPO Box 1680 DARWIN NT 0801 (08) 8924 7540 www.planningcommission.nt.gov.au ii FORWARD Following community engagement and input, the NT Planning Commission is pleased to release the draft Tennant Creek Land Use Plan for discussion. This is a long-term plan that identifies the land to support future growth. It provides land for urban residential and industrial purposes and reinforces the primacy of Paterson Street as the main retail and commercial centre of the township. It seeks to protect the long term sustainability of ground water resources by ensuring development is contained within defined future development areas. Planning is a detailed and complex process that works best when community and stakeholders are able to engage with planners at multiple points along the planning journey. The Draft Land Use Plan is Stage 2 of our community and stakeholder consultation process and follows preliminary consultations in November 2017 with the community and stakeholders. The Draft Plan is ready for you to view and discuss with us. We will again hold public information sessions as well as one-on-one meetings with key stakeholders in Tennant Creek – details are available on our website. Stage 2 consultations continue until 17 August 2018. -

Construction Snapshot October 2019 Edition Is Published by the Northern Territory Government’S Department of Infrastructure, Planning and Logistics

October 2019 Wishart – Truck Central - heavy vehicle inspection facility Construction Snapshot is published by the Department of Infrastructure, Planning and Logistics on a quarterly basis. The information provides an overview of the Northern Territory’s construction activity for major works over $500 000. It reflects work that is both currently underway and potential future construction- related work as at 1 October 2019. Table of contents IN PROGRESS ....................................................................................................................................... 4 TERRITORY WIDE ............................................................................................................................ 4 CENTRAL AUSTRALIA ..................................................................................................................... 4 BARKLY REGION ............................................................................................................................. 7 KATHERINE REGION ...................................................................................................................... 8 EAST ARNHEM REGION............................................................................................................... 11 TOP END RURAL ........................................................................................................................... 12 PALMERSTON and LITCHFIELD .................................................................................................. 14 DARWIN