Adult Learners and Student Engagement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategic Recruitment Strategies to Attract Students Into Chemistry and Physics Education

Strategic Recruitment Strategies to Attract Students into Chemistry and Physics Education Michelle L. Dean, Gregory Rushton, David Rosengrant & Brett Criswell The Need It has been echoed for numerous years that the nation needs STEM teachers who: • Are competent in the subject area • Offer quality education to their students by utilizing best practices • Will persist in the field Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences, and National Academy of Engineering. Rising Above the Gathering Storm: Energizing and Employing America for a Brighter Economic Future. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2007. National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine. Rising Above the Gathering Storm, Revisited: Rapidly Approaching Category 5. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2010. Landers, E. S., & Gates, Jr. S. J. (2010). Prepare and Inspire, 330 (6001), 151. White House Office of the Press Secretary (2012) President Obama announces plans for a new national corps to recognize and reward leading educators in science, technology, engineering and math. (Accessed Sept. 2014) Responses to the National Need • Development of alternative certification routes • Restructuring current education programs to draw students in (UTeach, PhysTec, Woodrow Wilson Fellows) • Incentives to pursue degrees in STEM education programs (Noyce, WWF, private scholarships, etc.) KSU Production of UG Biology & Chemistry Teachers 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Biology Chemistry Labor Market Theory • The basic principle driving the supply of teachers is the following: Individuals will become or remain teachers if teaching represents the most attractive activity to pursue among all activities available to them. • Making the career attractive and desirable –ease of entry and overall compensation (salary, benefits, working conditions, and personal satisfaction). -

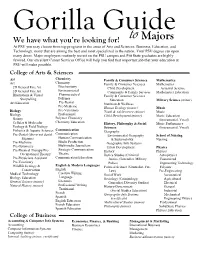

Gorilla Guide for Majors Activity

Gorilla Guide Gorilla Guide We have what you’re looking for! to Majors At PSU you may choose from top programs in the areas of Arts and Sciences, Business, Education, and Technology, many that are among the best and most specialized in the nation. Your PSU degree can open many doors. Major employers routinely recruit on the PSU campus and Pitt State graduates are highly favored. Our excellent Career Services Office will help you find that important job that your education at PSU will make possible. College of Arts & Sciences Art Chemistry Family & Consumer Sciences Mathematics Art Chemistry Family & Consumer Sciences Mathematics 2D General Fine Art Biochemistry Child Development Actuarial Science 3D General Fine Art Environmental Community & Family Services Mathematics Education Illustrations & Visual Pharmaceutical Family & Consumer Sciences Storytelling Polymer Education Military Science (minor) Art Education Pre-Dental Nutrition & Wellness Pre-Medicine Human Ecology (minor) Music Biology Pre-Veterinary Youth & Adolescence (minor) Music Biology Professional Child Development (minor) Music Education Botany Polymer Chemistry (Instrumental, Vocal) Cellular & Molecular Chemistry Education History, Philosophy & Social Music Performance Ecology & Field Biology Sciences (Instrumental, Vocal) Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences Communication Geography Pre-Dental (this is not dental Communication Environmental Geography School of Nursing hygiene) Human Communication & Sustainability Nursing Pre-Medicine Media Production Geographic Info Systems Pre-Optometry -

Pre-Service Physics and Chemistry Teachers' Conceptual Integration of Physics and Chemistry Concepts

Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science & Technology Education, 2016, 12(6), 1549-1568 doi: 10.12973/eurasia.2016.1244a Pre-Service Physics and Chemistry Teachers’ Conceptual Integration of Physics and Chemistry Concepts Mustafa Tuysuz Yuzuncu Yıl University, TURKEY Oktay Bektas Erciyes University, TURKEY Omer Geban & Gokhan Ozturk Middle East Technical University, TURKEY Bugrahan Yalvac Texas A&M University, USA Received 2 March 2015Revised 11 November 2015 Accepted 20 November 2015 This study examines the pre-service teachers’ opinions about conceptual integration (CI) and their understanding of it. A qualitative phenomenology design was used in the study. Data was collected through in-depth semi-structured interviews comprising ten guiding questions. Three pre-service physics and three pre-service chemistry teachers participated conveniently in the study. While the pre-service chemistry teachers took a course regarding the CI explicitly taught, the pre-service physics teachers were not subjected to any information relating to the CI in their course. Data was analyzed by forming the codes and themes. Generally speaking, while the pre-service chemistry teachers think that physics concepts should be used in the chemistry lessons, the pre- service physics teachers believe that these two subjects’ concepts generally are not related to each other. Moreover, the participants had some difficulties in understanding the CI between physics and chemistry concepts. The possible implication for science teacher education and research is discussed. Keywords: conceptual integration, chemistry education, physics education, pre-service teacher education INTRODUCTION In constructivist view, students interpret the new knowledge according to what Correspondence: Mustafa Tuysuz, Faculty of Education, Secondary Science and Mathematics Education Department, Middle East Technical University, 06800, Turkey. -

The Role of Mathematics in the Teaching and Learning of Physics

Strand 2 Learning science: Cognitive, affective and social aspects THE ROLE OF MATHEMATICS IN THE TEACHING AND LEARNING OF PHYSICS Andreas Redfors, Lena Hansson, Örjan Hansson and Kristina Juter Kristianstad University, Kristianstad, Sweden Abstract: This paper discusses the role of mathematics in physics teaching and learning. The intention and strength of science is to describe what happens in the real world by organizing explanations through theories and theoretical models. It has been widely suggested that learning in science is influenced by views about the nature of scientific knowledge. Furthermore, mathematics is an inherent part of theories and makes powerful predictions of natural phenomena possible. Ability to use mathe- matics to argue and prove results is central in physics. Students have been found to struggle with physics problems where they need to relate mathematically formulated theoretical models to the real world. This project has explored the role of mathematics for physics teaching and learning in upper-secondary school through investigations of relations made during physics lessons (lectures, problem solving and lab-work) between The real world – Theoretical models – Mathematics. A preliminary analysis indicate that there are some connections made by students and teacher between theories and the real world, but the bulk of the discussion in the classroom is con- cerning the relation between theoretical models and mathematics, which is in line with earlier research on problem solving. The preliminary results reported on here indicate that this also holds true for all the investigated organisational forms lectures, problem solving in groups and lab-work. A finalized and extended analysis will be published elsewhere. -

Chemistry and Physics 1

Chemistry and Physics 1 undergraduate-catalog/science/chemistry-physics/chemistry- CHEMISTRY AND PHYSICS education-bs-endorsement-secondary-education-chemistry/) • B.S. in Chemistry and Education with Endorsement in Secondary Chair: William Schreiber, Department of Chemistry and Physics Education in Physical Science (http://catalog.monmouth.edu/ undergraduate-catalog/science/chemistry-physics/chemistry- Our curricula provide foundations in the traditional chemistry sub- education-bs-endorsement-secondary-education-physical-science/) disciplines. The programs serve as excellent preparation for further professional study in chemistry and related sciences, health professions • B.S. in Chemistry with a Concentration in Advanced Chemistry (ACS such as medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, and physical therapy. Careers in Approved) (http://catalog.monmouth.edu/undergraduate-catalog/ academia, the chemical and pharmaceutical industries, environmental science/chemistry-physics/chemistry-bs-concentration-advanced- protection, forensics, government, industrial hygiene, information science, chemistry-acs-approved/) patent law, science writing, toxicology, and education are open to those • B.S. in Chemistry with a Concentration in Biochemistry (http:// whose initial field of study is chemistry. catalog.monmouth.edu/undergraduate-catalog/science/chemistry- physics/chemistry-bs-concentration-biochemistry/) The Bachelor of Science in Chemistry provides a core curriculum of chemistry while allowing sufficient flexibility to combine it with a second Minor major, -

Physics Education Model Schedule

PHYSICS EDUCATION PROGRAM OVERVIEW OF THE PROGRAM: The science education program is designed to provide a strong content background in one or more science disciplines and extensive practice using constructivist teaching strategies to prepare teacher candidates for today?s classroom. Certifications (specializations) are available in biology (9-adult), chemistry (9-adult), physics (9-adult), earth and space science (5-adult), and general science (5-adult). Our program provides early teaching opportunities in middle school classrooms, workshops in association with the NASA IV&V Educator Resource Center, participation in state science teacher conferences, membership in professional organizations, opportunities for international travel and public outreach, and research experiences using radio telescopes at the Green Bank Observatory in Green Bank, WV. Science education students earn the B.A. Degree in Education with specializations in two or more science areas. Some students choose to double major, earning both a B.S. in a science discipline (e.g., chemistry or biology) and a B.A. in Education. EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITIES: Students graduating from Fairmont State with science teaching specializations are typically recruited prior to graduation by area schools and/or by school districts in Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina. The biology, chemistry, earth and space, or physics certification coupled with a general science certification provides the widest range of teaching opportunities. Due to the shortage of science teachers, graduates with the science specialization are heavily recruited. GRADUATE OPPORTUNITIES: Many science education graduates eventually continue on in their education to pursue a Master of Education (M.Ed.) degree. The Master of Arts in Teaching (M.A.T.) degree is another option at Fairmont State for those who already have a bachelor?s degree or higher with substantial earth science content. -

Physics Education Research and Contexts of Student Learning Why

Physics Education Research and Contexts of Student Learning Why do university students exit courses capable of solving difficult analytic problems (e.g., calculate current in a complex circuit), but are unable to explain the same content conceptually (e.g., which light bulb is brighter in such a circuit)? Why do many of the educational reforms being called for today echo the calls of almost 100 years ago? Building on the well-established foundations of physics education research that have focused on student cognition, curriculum design and course practices, this research program establishes another perspective from which we may understand student learning in physics – one that emphasizes learning in context. The proposed work investigates the central role of context in the practice of physics education. That is, how and what students learn depends not only on traditionally conceived content but also upon the formation of tasks, class environments, and broader institutional structures in which the content is embedded. Such a perspective begins to explain a host of research questions, such as those listed above, and is directed at understanding sustainable and scalable models of reform in physics education. This project coordinates research studies on the role of context in student learning at three different levels: the individual, the course, and the department. Because these three contextual levels of educational practice strongly influence one another, they are studied simultaneously to discover the relations among them. While this project spans all three levels, it does not strive to answer all questions within them. Instead, the project focuses on specific sets of questions surrounding common themes: tools, such as the use of computer simulations; practices, such as teaching as a mechanism of learning; and surrounding frames, such as departmental norms and their influence on student learning. -

Improving Engineering Physics Teaching - Learning from Physics Education Research

IMPROVING ENGINEERING PHYSICS TEACHING - LEARNING FROM PHYSICS EDUCATION RESEARCH JONTE BERNHARD Campus Norrköping, Linköping University S-602 18 Norrköping, Sweden E-mail: [email protected], Homepage: http://www.itn.liu.se/~jonbe Abstract Students come to our courses with a personal theory of physics. Most students do not change their personal theories during a traditionally taught physics course. In this paper I will give some reasons for this and also highlight some successful active-engagement curricula who help students to modify their personal theories of physics and thus help them acquiring a good functional understanding of physics. Invited paper presented at Physics Teaching in Engineering Education (PTEE 2000), Budapest 13-17 June 2000. IMPROVING ENGINEERING PHYSICS TEACHING - LEARNING FROM PHYSICS EDUCATION RESEARCH JONTE BERNHARD Campus Norrköping, Linköping University S-602 18 Norrköping, Sweden E-mail: [email protected], Homepage: http://www.itn.liu.se/~jonbe Abstract Students come to our courses with a personal theory of physics. Most students do not change their personal theories during a traditionally taught physics course. In this paper I will give some reasons for this and also highlight some successful active-engagement curricula who help students to modify their personal theories of physics and thus help them acquiring a good functional understanding of physics. KEYWORDS: Physics Education Research. Introduction Some years ago I started to include some ”simple” conceptual questions in the exams of the physics courses I taught. These questions could be answered by qualitative reasoning and no or very simple calculations were needed. The results were first quite surprising: Most students performed very poorly on the conceptual questions which most physics would consider as to be almost ‘to easy’, while they sometimes solved ‘difficult’ multiple-step quantitative problems better than expected. -

Experiments As a Basis of Informal In-Service Training of Czech Physics Teachers

Experiments as a basis of informal in-service training of Czech physics teachers Cite as: AIP Conference Proceedings 2152, 030004 (2019); https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5124748 Published Online: 05 September 2019 Irena Dvořáková, and Petra Prošková ARTICLES YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN Views of physics teachers concerning possible reform of framework educational programs in the Czech Republic AIP Conference Proceedings 2152, 020001 (2019); https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5124741 Physicists as key players in developing a new physics curriculum AIP Conference Proceedings 2152, 030041 (2019); https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5124785 Inquiry-based science education as a support of school readiness AIP Conference Proceedings 2152, 020004 (2019); https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5124744 AIP Conference Proceedings 2152, 030004 (2019); https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5124748 2152, 030004 © 2019 Author(s). Experiments as a Basis of Informal In-service Training of Czech Physics Teachers Irena DvoĜáková1, a) and Petra Prošková2, b) 1Charles University, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Department of Physics Education. V Holešoviþkách 2, 180 00 Prague 8, Czech Republic. 2Elixir to Schools, Olbrachtova 1929/62,140 00 Praha 4, Czech Republic a) Corresponding author: [email protected] b)[email protected] Abstract. Experiments perform a number of functions in physics teaching - from a fun add-on of a very formal learning style to the cornerstone of a teaching method. A method of acquiring physical knowledge by using experiments, problem solving, tasks, etc. is a basic approach of teaching physics according to the Heureka (in English “Eureka”) project. Students are guided to analyse and solve scientific issues whereby they discover inquire new physical principles. -

A Synthesis of Discipline-Based Education Research in Physics Jennifer L

A Synthesis of Discipline-Based Education Research in Physics Jennifer L. Docktor & José P. Mestre University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Introduction................................................................................................................................2 Conceptual Change.....................................................................................................................4 Misconceptions.....................................................................................................................11 Knowledge in Pieces or Resources........................................................................................12 Ontological Categories..........................................................................................................12 Problem Solving.......................................................................................................................19 Expert-Novice Studies..........................................................................................................25 Worked Examples.................................................................................................................26 Representations.....................................................................................................................28 Mathematics in Physics.........................................................................................................29 Instructional Strategies..........................................................................................................31 -

Evaluating High School Students' Conceptions of The

Science Education International Vol. 27, Issue2, 2016, 253-276 Evaluating High School Students’ Conceptions of the Relationship between Mathematics and Physics: Development of A Questionnaire S. KAPUCU*, M. F. ÖÇAL, M. ŞİMŞEK ABSTRACT: The purposes of this study were (1) to develop a questionnaire measuring high school students’ conceptions of the relationship between mathematics and physics, (2) and to determine the students’ conceptions of the relationship between mathematics and physics. A total of 718 high school students (343 male, 375 female) participated in this study. Espousing a phenomenographic approach, a Relationship between Mathematics and Physics Questionnaire (RMPQ) was first developed. Then explanatory factor analysis (EFA) to identify factor structure and confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to verify the EFA results were performed on the data obtained. Data analyses showed that the RMPQ was a reliable and valid instrument to identify the students’ conceptions of the relationship between mathematics and physics. Descriptive results also revealed that the majority of the students believed that mathematics and physics closely related to each other in terms of their content and daily-life relations. They also believed that mathematics was needed to understand physics. KEY WORDS: conceptions, mathematics, physics, phenomenographic approach, questionnaire development INTRODUCTION It is inevitable for students who study physics to use mathematics so as to be able to solve some physics problems (Basson, 2002; Bing &Redish, 2006; Woolnough, 2000). Students need to have a deep understanding of mathematics and utilize it when necessary while engaging with physics concepts (Ataide&Greca, 2013). Even in the explanation of basic concepts in physics, students bring required components from mathematics, including symbols, structures and algebraic equations, and embed them into the problem situations by combining the mathematics and physics concepts (Ataide&Greca, 2013; Hudson & McIntire, 1977). -

What Physics Should We Teach?

Proceedings of the International Physics Education Conference, 5 to 8 July 2004, Durban, South Africa What Physics Should We Teach? Edited by Diane J. Grayson Sponsored by the International Commission on Physics Education and the South African Institute of Physics International Advisory Committee Igal Galili (Israel) Priscilla Laws (USA) Inocente Multimucuio (Mozambique) Jon Ogborn (UK) Joe Redish (USA) Khalijah Salleh (Malaysia) David Schuster (USA/ South Africa) Gunnar Tibell (Sweden) Matilde Vicentini (Italy) Laurence Viennot (France) Conference Organiser Diane Grayson Local Organisers Sandile Malinga Jaynie Padayachee Sadha Pillay. Robynne Savic and Carmen Fitzgerald (Interaction Conferencing) Editorial Assistant Erna Basson Administrative Assistant Ignatious Dire Cover Design: Joerg Ludwig © 2005 International Commission on Physics Education ISBN 1-86888-359 University of South Africa Press, PO Box 392, UNISA 0003, South Africa TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................... 2 Citation for the Presentation of the Medal.................................................................................... 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS......................................................................................................... 7 PAPERS BY PLENARY SPEAKERS ........................................................................................ 8 QUANTUM GRAVITY FOR UNDERGRADUATES? .............................................................