Water Quality Impacts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Susquehanna Riyer Drainage Basin

'M, General Hydrographic Water-Supply and Irrigation Paper No. 109 Series -j Investigations, 13 .N, Water Power, 9 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIRECTOR HYDROGRAPHY OF THE SUSQUEHANNA RIYER DRAINAGE BASIN BY JOHN C. HOYT AND ROBERT H. ANDERSON WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1 9 0 5 CONTENTS. Page. Letter of transmittaL_.__.______.____.__..__.___._______.._.__..__..__... 7 Introduction......---..-.-..-.--.-.-----............_-........--._.----.- 9 Acknowledgments -..___.______.._.___.________________.____.___--_----.. 9 Description of drainage area......--..--..--.....-_....-....-....-....--.- 10 General features- -----_.____._.__..__._.___._..__-____.__-__---------- 10 Susquehanna River below West Branch ___...______-_--__.------_.--. 19 Susquehanna River above West Branch .............................. 21 West Branch ....................................................... 23 Navigation .--..........._-..........-....................-...---..-....- 24 Measurements of flow..................-.....-..-.---......-.-..---...... 25 Susquehanna River at Binghamton, N. Y_-..---...-.-...----.....-..- 25 Ghenango River at Binghamton, N. Y................................ 34 Susquehanna River at Wilkesbarre, Pa......_............-...----_--. 43 Susquehanna River at Danville, Pa..........._..................._... 56 West Branch at Williamsport, Pa .._.................--...--....- _ - - 67 West Branch at Allenwood, Pa.....-........-...-.._.---.---.-..-.-.. 84 Juniata River at Newport, Pa...-----......--....-...-....--..-..---.- -

Natural Areas Inventory of Bradford County, Pennsylvania 2005

A NATURAL AREAS INVENTORY OF BRADFORD COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA 2005 Submitted to: Bradford County Office of Community Planning and Grants Bradford County Planning Commission North Towanda Annex No. 1 RR1 Box 179A Towanda, PA 18848 Prepared by: Pennsylvania Science Office The Nature Conservancy 208 Airport Drive Middletown, Pennsylvania 17057 This project was funded in part by a state grant from the DCNR Wild Resource Conservation Program. Additional support was provided by the Department of Community & Economic Development and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service through State Wildlife Grants program grant T-2, administered through the Pennsylvania Game Commission and the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. ii Site Index by Township SOUTH CREEK # 1 # LITCHFIELD RIDGEBURY 4 WINDHAM # 3 # 7 8 # WELLS ATHENS # 6 WARREN # # 2 # 5 9 10 # # 15 13 11 # 17 SHESHEQUIN # COLUMBIA # # 16 ROME OR WELL SMITHFI ELD ULSTER # SPRINGFIELD 12 # PIKE 19 18 14 # 29 # # 20 WYSOX 30 WEST NORTH # # 21 27 STANDING BURLINGTON BURLINGTON TOWANDA # # 22 TROY STONE # 25 28 STEVENS # ARMENIA HERRICK # 24 # # TOWANDA 34 26 # 31 # GRANVI LLE 48 # # ASYLUM 33 FRANKLIN 35 # 32 55 # # 56 MONROE WYALUSING 23 57 53 TUSCARORA 61 59 58 # LEROY # 37 # # # # 43 36 71 66 # # # # # # # # # 44 67 54 49 # # 52 # # # # 60 62 CANTON OVERTON 39 69 # # # 42 TERRY # # # # 68 41 40 72 63 # ALBANY 47 # # # 45 # 50 46 WILMOT 70 65 # 64 # 51 Site Index by USGS Quadrangle # 1 # 4 GILLETT # 3 # LITCHFIELD 8 # MILLERTON 7 BENTLEY CREEK # 6 # FRIENDSVILLE # 2 SAYRE # WINDHAM 5 LITTLE MEADOWS 9 -

Bradford County, Pennsylvania 2020 Hazard Mitigation Plan DRAFT

Bradford County, Pennsylvania 2020 Hazard Mitigation Plan DRAFT Certification of Annual Review Meetings PUBLIC DATE OF YEAR OUTREACH SIGNATURE MEETING ADDRESSED? * 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 *Confirm yes here annually and describe on record of change page. i Bradford County, Pennsylvania 2020 Hazard Mitigation Plan DRAFT Record of Changes DESCRIPTION OF CHANGE MADE, MITIGATION ACTION COMPLETED, CHANGE MADE CHANGE MADE DATE OR PUBLIC OUTREACH BY (PRINT NAME) BY (SIGNATURE) PERFORMED REMINDER: Please attach all associated meeting agendas, sign-in sheets, handouts and minutes. ii Bradford County, Pennsylvania 2020 Hazard Mitigation Plan DRAFT Table of Contents Certification of Annual Review Meetings ....................................................................... i Record of Changes ....................................................................................................... ii Figures ....................................................................................................................... vi Tables ........................................................................................................................ vii 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Background .................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Purpose ........................................................................................................... 2 1.3. Scope ............................................................................................................. -

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy Introduction Brook Trout symbolize healthy waters because they rely on clean, cold stream habitat and are sensitive to rising stream temperatures, thereby serving as an aquatic version of a “canary in a coal mine”. Brook Trout are also highly prized by recreational anglers and have been designated as the state fish in many eastern states. They are an essential part of the headwater stream ecosystem, an important part of the upper watershed’s natural heritage and a valuable recreational resource. Land trusts in West Virginia, New York and Virginia have found that the possibility of restoring Brook Trout to local streams can act as a motivator for private landowners to take conservation actions, whether it is installing a fence that will exclude livestock from a waterway or putting their land under a conservation easement. The decline of Brook Trout serves as a warning about the health of local waterways and the lands draining to them. More than a century of declining Brook Trout populations has led to lost economic revenue and recreational fishing opportunities in the Bay’s headwaters. Chesapeake Bay Management Strategy: Brook Trout March 16, 2015 - DRAFT I. Goal, Outcome and Baseline This management strategy identifies approaches for achieving the following goal and outcome: Vital Habitats Goal: Restore, enhance and protect a network of land and water habitats to support fish and wildlife, and to afford other public benefits, including water quality, recreational uses and scenic value across the watershed. Brook Trout Outcome: Restore and sustain naturally reproducing Brook Trout populations in Chesapeake Bay headwater streams, with an eight percent increase in occupied habitat by 2025. -

2018 Pennsylvania Summary of Fishing Regulations and Laws PERMITS, MULTI-YEAR LICENSES, BUTTONS

2018PENNSYLVANIA FISHING SUMMARY Summary of Fishing Regulations and Laws 2018 Fishing License BUTTON WHAT’s NeW FOR 2018 l Addition to Panfish Enhancement Waters–page 15 l Changes to Misc. Regulations–page 16 l Changes to Stocked Trout Waters–pages 22-29 www.PaBestFishing.com Multi-Year Fishing Licenses–page 5 18 Southeastern Regular Opening Day 2 TROUT OPENERS Counties March 31 AND April 14 for Trout Statewide www.GoneFishingPa.com Use the following contacts for answers to your questions or better yet, go onlinePFBC to the LOCATION PFBC S/TABLE OF CONTENTS website (www.fishandboat.com) for a wealth of information about fishing and boating. THANK YOU FOR MORE INFORMATION: for the purchase STATE HEADQUARTERS CENTRE REGION OFFICE FISHING LICENSES: 1601 Elmerton Avenue 595 East Rolling Ridge Drive Phone: (877) 707-4085 of your fishing P.O. Box 67000 Bellefonte, PA 16823 Harrisburg, PA 17106-7000 Phone: (814) 359-5110 BOAT REGISTRATION/TITLING: license! Phone: (866) 262-8734 Phone: (717) 705-7800 Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. The mission of the Pennsylvania Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. Monday through Friday PUBLICATIONS: Fish and Boat Commission is to Monday through Friday BOATING SAFETY Phone: (717) 705-7835 protect, conserve, and enhance the PFBC WEBSITE: Commonwealth’s aquatic resources EDUCATION COURSES FOLLOW US: www.fishandboat.com Phone: (888) 723-4741 and provide fishing and boating www.fishandboat.com/socialmedia opportunities. REGION OFFICES: LAW ENFORCEMENT/EDUCATION Contents Contact Law Enforcement for information about regulations and fishing and boating opportunities. Contact Education for information about fishing and boating programs and boating safety education. -

Estimation of Suspended Sediment Concentrations and Loads Using Continuous Turbidity Data

Estimation of Suspended Sediment Concentrations and Loads Using Continuous Turbidity Data Pub. No. 306 September 2016 Luanne Y. Steffy Aquatic Ecologist Susquehanna River Basin Commission TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 METHODS ..................................................................................................................................... 3 RESULTS ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Turbidity Method ........................................................................................................................ 5 Calculation of Sediment Loads ............................................................................................... 5 Relationships Between Land Use and Suspended Sediment Yields ....................................... 8 Impacts of Storm Events ....................................................................................................... 10 Flow Method Comparison ........................................................................................................ 12 CONCLUSIONS........................................................................................................................... 17 LESSONS LEARNED.................................................................................................................. 18 APPLICATIONS ......................................................................................................................... -

Bradford County

BRADFORD COUNTY START BRIDGE SD MILES PROGRAM IMPROVEMENT TYPE TITLE DESCRIPTION COST PERIOD COUNT COUNT IMPROVED Bridge superstructure rehabilitation on PA 514 over the North Branch of Towanda BASE Bridge Rehabilitation PA 514 over the North Branch of Towanda Creek Creek in Granville Township 1 $ 1,000,000 1 0 0 BASE Bridge Replacement PA 414 over Towanda Creek Bridge replacement on PA 414 over Towanda Creek in Franklin Township 1 $ 2,000,000 1 1 0 Bridge replacement on State Route 1026 over Tributary to Wyalusing Creek in Pike BASE Bridge Replacement State Route 1026 over Tributary to Wyalusing Creek Township 1 $ 140,000 1 1 0 BASE Bridge Replacement PA 367 over Steam Mill Creek Bridge replacement on PA 367 over Steam Mill Creek in Tuscarora Township 2 $ 740,000 1 1 0 Bridge superstructure rehabilitation on PA 367 over Fargo Creek in Tuscarora BASE Bridge Rehabilitation PA 367 over Fargo Creek Township 3 $ 1,120,000 1 1 0 Township Road 402 over the South Branch of Towanda Bridge replacement on Township Road 402 over the South Branch of Towanda BASE Bridge Replacement Creek Creek in Monroe Township 1 $ 1,050,000 1 1 0 Bridge replacement on Township Road 623 over Tomjack Creek in Smithfield BASE Bridge Replacement Township Road 623 over Tomjack Creek Township 1 $ 600,000 1 1 0 Bridge replacement on US 6 over Sugar Creek in Columbia Township and a Bridge Superstructure Rehabilitation on US 6 over Sugar Creek in West Burlington BASE Bridge Replacement US 6 over Sugar Creek Township 1 $ 1,134,000 2 2 0 BASE Bridge Replacement State Route -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

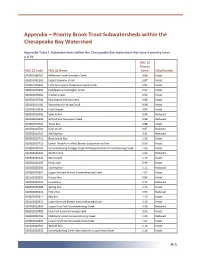

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds Within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Appendix Table I. Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay watershed that have a priority score ≥ 0.79. HUC 12 Priority HUC 12 Code HUC 12 Name Score Classification 020501060202 Millstone Creek-Schrader Creek 0.86 Intact 020501061302 Upper Bowman Creek 0.87 Intact 020501070401 Little Nescopeck Creek-Nescopeck Creek 0.83 Intact 020501070501 Headwaters Huntington Creek 0.97 Intact 020501070502 Kitchen Creek 0.92 Intact 020501070701 East Branch Fishing Creek 0.86 Intact 020501070702 West Branch Fishing Creek 0.98 Intact 020502010504 Cold Stream 0.89 Intact 020502010505 Sixmile Run 0.94 Reduced 020502010602 Gifford Run-Mosquito Creek 0.88 Reduced 020502010702 Trout Run 0.88 Intact 020502010704 Deer Creek 0.87 Reduced 020502010710 Sterling Run 0.91 Reduced 020502010711 Birch Island Run 1.24 Intact 020502010712 Lower Three Runs-West Branch Susquehanna River 0.99 Intact 020502020102 Sinnemahoning Portage Creek-Driftwood Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.03 Intact 020502020203 North Creek 1.06 Reduced 020502020204 West Creek 1.19 Intact 020502020205 Hunts Run 0.99 Intact 020502020206 Sterling Run 1.15 Reduced 020502020301 Upper Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.07 Intact 020502020302 Kersey Run 0.84 Intact 020502020303 Laurel Run 0.93 Reduced 020502020306 Spring Run 1.13 Intact 020502020310 Hicks Run 0.94 Reduced 020502020311 Mix Run 1.19 Intact 020502020312 Lower Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.13 Intact 020502020403 Upper First Fork Sinnemahoning Creek 0.96 -

Pennsylvania Angler (1SSN0O31-434X) Is Published Monthly by Ihe Pennsylvania's Biggest Smallmouth Bass: Pennsylvania Fish & Boat Commission, 35.12 Walnut Street

SV,i§- m <.>* V «|3B Pennsylvania Hosts East Coast Trout Managers On June 23-25, 1992, the American Fisheries Society (AFS) and other sponsors held a three-day Trout Culture and Management Workshop at Penn State. The intent of the workshop was fourfold: (1) assess the state of knowledge on the East Coast; (2) develop new working relationships among the states; (3) learn to do jobs more effectively; and (4) encourage the participation of anglers in workshop sessions. In Pennsylvania, the word trout means many things to many people. To sportsmen, it means a variety of fishing opportunities. Fishermen spend over 17 million hours a year fishing for trout on inland waters, making more than 6.7 million annual fishing trips. Commission staff estimates that 5.4 million trout are harvested each year and millions more are caught and released. To the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission and its employees, trout means the kingpin of its many popular programs. Over the past decades the Commission has gained wide recognition for its broad approach to trout management. Its coldwater fish culture system and trout stocking programs lead all but a few states, and its coldwater stream and lake classification system and stocking allocation methods are nationally recognized. The Adopt-a-Stream Program, with its major thrust toward habitat improvement and public access, serves as a model to many. Pennsylvania is also recognized as the nation's leader for its Cooperative Nursery Program, which involves sportsmen directly in the many facets of hatchery creation, operation and fish production. Its bio-engineering approach to solving fishery resource problems has been a leader and the Commission's staff has been active in many professional organizations. -

FFY 2009 Northern Tier TIP Highway & Bridge

FFY 2009 Northern Tier TIP Highway & Bridge Original US DOT Approval Date: 10/01/2008 Current Date: 06/30/2010 Bradford MPMS #: 65102 Municipality: Title: RR Line Item NorthernTier Route: Section: A/Q Status: Improvement Type: RR High Type Crossing Est. Let Date: Actual Let Date: Geographic Limits: Northern Tier Region of District 3Miscellaneous Projects Narrative: (Tioga, Sullivan, and Bradford Counties) - Miscellaneous Projects - Rail Crossing Improvements TIP Program Years ($000) Phase Fund FY 2009 FY 2010 FY 2011 FY 2012 2nd 4 Years 3rd 4 Years CONRRX $43 $2 $46 $48 $0 $0 $43 $2 $46 $48 $0 $0 Total FY 2009-2012 Cost $139 MPMS #: 71069 Municipality: Title: Enhancment Line Item Route: Section: A/Q Status: Improvement Type: Transportation Enhancement Est. Let Date: Actual Let Date: Geographic Limits: Northern Tier RegionEnhancement Line Item Narrative: (Bradford, Sullivan and Tioga Counties) - Transportation Enhancement Line Item TIP Program Years ($000) Phase Fund FY 2009 FY 2010 FY 2011 FY 2012 2nd 4 Years 3rd 4 Years CONSTE $435 $102 $470 $489 $0 $0 $435 $102 $470 $489 $0 $0 Total FY 2009-2012 Cost $1,496 MPMS #: 85224 Municipality: Title: Endless Mt. Facility Route: Section: A/Q Status: Improvement Type: Miscellaneous Est. Let Date: Actual Let Date: Geographic Limits: Endless Mountains. Narrative: Public Transit Facility-Flex TIP Program Years ($000) Phase Fund FY 2009 FY 2010 FY 2011 FY 2012 2nd 4 Years 3rd 4 Years CONSTP $65 $0 $0 $0 $0 $0 CONGEN $16 $0 $0 $0 $0 $0 $81 $0 $0 $0 $0 $0 Total FY 2009-2012 Cost $81 Page 1 of 152 FFY 2009 Northern Tier TIP Highway & Bridge Original US DOT Approval Date: 10/01/2008 Current Date: 06/30/2010 Bradford MPMS #: 86604 Municipality: Title: Group 3-08-RPM Route: Section: A/Q Status: Improvement Type: Reflective Pavement Markers Est. -

Bradford County, Pennsylvania 2005

A NATURAL AREAS INVENTORY OF BRADFORD COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA 2005 Submitted to: Bradford County Office of Community Planning and Grants Bradford County Planning Commission North Towanda Annex No. 1 RR1 Box 179A Towanda, PA 18848 Prepared by: Pennsylvania Science Office The Nature Conservancy 208 Airport Drive Middletown, Pennsylvania 17057 This project was funded in part by a state grant from the DCNR Wild Resource Conservation Program. Additional support was provided by the Department of Community & Economic Development and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service through State Wildlife Grants program grant T-2, administered through the Pennsylvania Game Commission and the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. ii Site Index by Township SOUTH CREEK # 1 # LITCHFIELD RIDGEBURY 4 WINDHAM # 3 # 7 8 # WELLS ATHENS # 6 WARREN # # 2 # 5 9 10 # # 15 13 11 # 17 SHESHEQUIN # COLUMBIA # # 16 ROME OR WELL SMITHFI ELD ULSTER # SPRINGFIELD 12 # PIKE 19 18 14 # 29 # # 20 WYSOX 30 WEST NORTH # # 21 27 STANDING BURLINGTON BURLINGTON TOWANDA # # 22 TROY STONE # 25 28 STEVENS # ARMENIA HERRICK # 24 # # TOWANDA 34 26 # 31 # GRANVI LLE 48 # # ASYLUM 33 FRANKLIN 35 # 32 55 # # 56 MONROE WYALUSING 23 57 53 TUSCARORA 61 59 58 # LEROY # 37 # # # # 43 36 71 66 # # # # # # # # # 44 67 54 49 # # 52 # # # # 60 62 CANTON OVERTON 39 69 # # # 42 TERRY # # # # 68 41 40 72 63 # ALBANY 47 # # # 45 # 50 46 WILMOT 70 65 # 64 # 51 Site Index by USGS Quadrangle # 1 # 4 GILLETT # 3 # LITCHFIELD 8 # MILLERTON 7 BENTLEY CREEK # 6 # FRIENDSVILLE # 2 SAYRE # WINDHAM 5 LITTLE MEADOWS 9