Mediation, Improvisations, and All That Jazz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discography Updates (Updated May, 2021)

Discography Updates (Updated May, 2021) I’ve been amassing corrections and additions since the August, 2012 publication of Pepper Adams’ Joy Road. Its 2013 paperback edition gave me a chance to overhaul the Index. For reasons I explain below, it’s vastly superior to the index in the hardcover version. But those are static changes, fixed in the manuscript. Discographers know that their databases are instantly obsolete upon publication. New commercial recordings continue to get released or reissued. Audience recordings are continually discovered. Errors are unmasked, and missing information slowly but surely gets supplanted by new data. That’s why discographies in book form are now a rarity. With the steady stream of updates that are needed to keep a discography current, the internet is the ideal medium. When Joy Road goes out of print, in fact, my entire book with updates will be posted right here. At that time, many of these changes will be combined with their corresponding entries. Until then, to give you the fullest sense of each session, please consult the original entry as well as information here. Please send any additions, corrections or comments to http://gc-pepperadamsblog.blogspot.com/, despite the content of the current blog post. Addition: OLIVER SHEARER 470900 September 1947, unissued demo recording, United Sound Studios, Detroit: Willie Wells tp; Pepper Adams cl; Tommy Flanagan p; Oliver Shearer vib, voc*; Charles Burrell b; Patt Popp voc.^ a Shearer Madness (Ow!) b Medley: Stairway to the Stars A Hundred Years from Today*^ Correction: 490900A Fall 1949 The recording was made in late 1949 because it was reviewed in the December 17, 1949 issue of Billboard. -

The 2017 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2017 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

4-3 NEA JAZZ.qxp_WPAS 3/24/17 8:41 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN, Chairman DEBoRAh F. RUTTER, President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 3, 2017 at 7:30 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2017 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2017 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters DEE DEE BRIDGEWATER IRA GITLER DAVE HOLLAND DICK HYMAN DR. LONNIE SMITH Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz. This performance will be livestreamed online, and will be broadcast on Sirius XM Satellite Radio. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 4-3 NEA JAZZ.qxp_WPAS 3/24/17 8:41 AM Page 2 THE 2017 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts DEBORAH F. RUTTER, President of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts KENNY BARRON, NEA Jazz Master DAN MORGENSTERN, NEA Jazz Master GARY GIDDINS, jazz and film critic JESSYE NORMAN, Kennedy Center Honoree and recipient, National Medal of Arts The 2017 NEA JAzz MASTERS Performances by PAQUITO D’RIVERA, saxophone LEE KONITz, alto saxophone Special Guests Bill Charlap, piano Sherrie Maricle and the Theo Croker, trumpet DIVA Jazz Orchestra Aaron Diehl, piano Sherrie Maricle, leader and drummer Robin Eubanks, trombone Tomoko Ohno, piano James Genus, bass Noriko Ueda, bass Donald Harrison, saxophone Jennifer Krupa , lead trombonist Booker T. -

Dee Dee Bridgewater

B.H. Hopper Management Stievestr. 9 - D-80638 München - Tel. +49 (0)89-177031 - Fax. +49 (0)89-177067 email: [email protected] - http://www.hopper-management.com DEE DEE BRIDGEWATER Biography Today Dee Dee is a sparkling ambassador for jazz, but she bathed in its music before she could walk: her mother played the greatest albums of Ella Fitzgerald for her, and her father was a trumpeter who taught music - to Booker Little, Charles Lloyd and George Coleman, amongst others - and who also played in the summer with Dinah Washington. It's the kind of background that leaves its mark on an adolescent, especially one who appeared solo and with a trio as soon as she was able. Dee Dee's other vocation, that of a globetrotter, reared its head when she toured the Soviet Union, in 1969, with the University of Illinois Big Band. A year later, she followed her then husband, Cecil Bridgewater, to New York. Cecil was playing with pianist Horace Silver, and Dee Dee's dream was to sing Horace's compositions one day... Love and Peace, (Verve), her irresistible 1994 album, was that same dream come true. The young singer made an earth-shattering debut in New York; for four years she was the lead vocalist with the band led by Thad Jones and Mel Lewis, an early career marked by concerts and recordings with such authentic giants as Sonny Rollins, Dizzy Gillespie, Dexter Gordon, Max Roach, Roland Kirk... and also rich experiences with Norman Connors, Stanley Clarke, and Frank Foster's "Loud Minority". -

Dee Dee Bridgewater <I Class="Fa Fa-Qrcode" Title="Мероприятие COVID-FREE" Style="Color

МЕРОПРИЯТИЕ COVID-FREE • Обязательно предъявление QR-кода и документа, удостоверяющего личность; • Прохождение термометрии; • Наличие защитной маски при входе. Подробнее Ди Ди Бриджуотер — одна из лучших вокалисток современного джазового мэйнстрима, суперзвезда, умеющая с первых минут появления на сцене покорить самую взыскательную публику и критику. Она выступала и записывалась с лучшими джазовыми музыкантами, среди которых — Рей Чарльз, Джордж Бенсон, Сонни Роллинз, Диззи Гиллеспи, Декстер Гордон, Макс Роуч. Для полной реализации своего таланта Бриджуотер в 30 лет решилась на смелый шаг: она покинула Родину, переехала в Париж и начала там музыкальную карьеру с чистого листа. Именно Франция по-настоящему раскрыла ее талант величайшей джазовой певицы и театральной актрисы. Здесь она создала свой джаз-бэнд и получила признание. Ди Ди Бриджуотер работала в телешоу с великим Шарлем Азновуром. Благодаря своей общественной активности она стала первой американкой, вошедшей в состав Высшего совета франкофонии — государственного органа защиты и развития культуры Франции. В 2005 году Ди Ди Бриджуотер выбрали Послом ООН по вопросам продовольствия и сельского хозяйства. В этом качестве она объездила десятки стран, в том числе на Африканском континенте, внося посильный вклад в решение проблемы недоедания и голода. Ди Ди Бриджуотер родилась в Мемфисе 27 мая 1950 года. Росла под пение Эллы Фицджералд, чьи пластинки без конца слушала мать, и звуки трубы, на которой играл отец — не только первоклассный трубач и педагог, среди учеников которого были саксофонисты Чарлз Ллойд и Джордж Коулман, но и ди-джей на WDIA, ведущей радиостанции в Мемфисе. В ансамбле, где играл её отец, девочка получила свой первый профессиональный опыт. Начав петь в университетском биг-бэнде (с которым, кстати, приезжала в СССР в 1969 г.), она познакомилась с трубачом Сесилом Бриджуотером, за которого вышла замуж и переехала в Нью-Йорк. -

BENNY GOLSON NEA Jazz Master (1996)

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. BENNY GOLSON NEA Jazz Master (1996) Interviewee: Benny Golson (January 25, 1929 - ) Interviewer: Anthony Brown with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: January 8-9, 2009 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 119 pp. Brown: Today is January 8th, 2009. My name is Anthony Brown, and with Ken Kimery we are conducting the Smithsonian National Endowment for the Arts Oral History Program interview with Mr. Benny Golson, arranger, composer, elder statesman, tenor saxophonist. I should say probably the sterling example of integrity. How else can I preface my remarks about one of my heroes in this music, Benny Golson, in his house in Los Angeles? Good afternoon, Mr. Benny Golson. How are you today? Golson: Good afternoon. Brown: We’d like to start – this is the oral history interview that we will attempt to capture your life and music. As an oral history, we’re going to begin from the very beginning. So if you could start by telling us your first – your full name (given at birth), your birthplace, and birthdate. Golson: My full name is Benny Golson, Jr. Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The year is 1929. Brown: Did you want to give the exact date? Golson: January 25th. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 Brown: That date has been – I’ve seen several different references. Even the Grove Dictionary of Jazz had a disclaimer saying, we originally published it as January 26th. -

Mahomet, Illinois, a Unit of the Champaign County Forest Preserve District, in Mahomet, Illinois Doris K

Museum of the Grand Prairie (formerly Early American Museum), Mahomet, Illinois, a unit of the Champaign County Forest Preserve District, in Mahomet, Illinois Doris K. Wylie Hoskins Archive for Cultural Diversity Finding Aid (includes Scope and Content Note) for visitor use Compiled by interns Rebecca Vaughn and Katherine Hicks Call to schedule an appointment to visit the Doris Hoskins Archive (217-586-2612) Museum website: http://www.museumofthegrandprairie.org/index.html Scope and Content Note Biographical Note Mrs. Doris Baker (Wylie) Hoskins, was born October 18, 1911 in Champaign, Illinois, and passed away in September, 2004, in Champaign, Illinois. She served for many years with the Committee on African American History in Champaign County of the former Early American Museum (now Museum of the Grand Prairie), serving as the group's archivist. She was also active in the Champaign County Section of the National Council of Negro Women. Her collection of historical material was transferred to Cheryl Kennedy upon her passing. The Hoskins Archive is now made publicly accessible by the staff of the Museum of the Grand Prairie, Champaign County Forest Preserve District, and inquiries should be made to Cheryl Kennedy, Museum Director, [email protected] (cited in eBlackCU.net Doris K. Wylie Hoskins Archive description). Hoskins Archive Summary The Doris K. Wylie Hoskins Archive for Cultural Diversity contains a wide body of materials featuring African American history in Champaign County and East Central Illinois. The date range for the archives contents extends from 1861 to 2010. The ―bulk dates‖ or dates that the majority of the file contents fall under, range from 1930 to 2000. -

Max Roach Quartet in the Light Mp3, Flac, Wma

Max Roach Quartet In The Light mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: In The Light Country: Italy Released: 1983 Style: Post Bop, Hard Bop, Free Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1498 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1492 mb WMA version RAR size: 1483 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 806 Other Formats: AIFF AAC MP3 AHX ASF APE AC3 Tracklist Hide Credits In The Light A1 8:40 Written-By – Max Roach Straight No Chaser A2 7:00 Written-By – Thelonious Monk Ruby My Dear A3 4:53 Written-By – Thelonious Monk Henry Street Blues B1 4:48 Written-By – Max Roach If You Could See Me Now B2 4:27 Written-By – Tadd Dameron Good Bait B3 7:38 Written-By – Tadd Dameron Tricotism B4 4:20 Written-By – Oscar Pettiford Companies, etc. Recorded At – Barigozzi Studio Credits Artwork [Cover] – Pick Up Studios Bass – Calvin Hill Drums – Max Roach Engineer – Giancarlo Barigozzi Liner Notes – Nat Hentoff Photography By [Cover] – Renzo Chiesa Producer – Giovanni Bonandrini Tenor Saxophone – Odean Pope Trumpet, Flugelhorn – Cecil Bridgewater Notes Recorded at Barigozzi Studio in Milano, Italy on July 22 & 23, 1982. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year In The Light (CD, Album, SN 1053CD Max Roach Quartet Soul Note SN 1053CD Japan 1983 RE) 121053-2 Max Roach Quartet In The Light (CD) Soul Note 121053-2 Italy 1983 Related Music albums to In The Light by Max Roach Quartet Guido Manusardi Trio - Down Town Barigozzi / Rocchi / Milano / Pillot - Quartetto Jazz Thelonious Monk And Max Roach - European Tour Thelonious Monk - The Riverside Years Thelonious Monk - Riverside Profiles: Thelonious Monk Thelonious Monk Quintet - Brilliant Corners Aida And Cooper Terry Revue - Feelin' Good Steve Lacy - Only Monk Fats Navarro Featured With The Tadd Dameron Quintet - Fats Navarro Featured With The Tadd Dameron Quintet Max Roach Double Quartet - Live At Vielharmonie. -

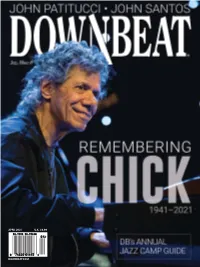

Downbeat.Com April 2021 U.K. £6.99

APRIL 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM April 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Morgenstern, Dan. [Record Review: University of Illinois Jazz Band: In

Blfles No. 2; Were You There Wl tries to keep afloat. Cmcified My Lord; Shine. ,en They One other very nice thing: McCann's .P<:rsonncl: To'!lmy Gwaltney, clarinet· Sa R,mington, clarinet, alto saxophone·' w!my vocal on Hands. Poignant, simple, and (Slide) Harris, trombone· Bob Gree.{e .a ter 1 0 • propelled sympathetically to a strong cli Van Perry, bass; Singleto~, drums· Job.{s P ;'!,; max. It sounds, however, like either the Ree, Jr., vocals. ' on .1.n.c- vocal or the piano was added later, be Rating: *** 1azz cause the piano's rhythmic direction at These sessions were .~roduced by John BY times runs directly counter to what Mc son McRee, Jr., a traditional jazz enthusi Cann is attempting vocally. Still, a mov ast and promoter of Manassas, Va. ing rendition, Veteran dru~mer Singleton, in his first Eddie Sauter demonstrated some years own LP date, 1s matched with an assem MPS·SABA bly of stalwart traditionalists, and though ago how strings could enhance jazz of a for collectors & there are weaknesses throughout, there are swinging, lyrical nature. With the possible connoisseurs ..• also. counterbalancing st:etches of quality from Germany, exception of a very few of Bird's string settings, no one had emerged with a work p~ay~ng, generated especially by Singleton, "the .Jazz musician's able melange of strings and down-with piamst Greene, and Rimington and Gwalt ney. paradise!" it jazz. Fischer, apparently, has done it. Makes the record worth hearing if not The most exciting tracks are those having. -Heineman where the clarinetists match wits. -

Leadership Profile

LEADERSHIP PROFILE DIRECTOR OF THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC CARLE ILLINOIS COLLEGE OF MEDICINE Founded in 1867 as a land grant institution, the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign recently celebrated 150 years of transformative experiences and heralded an ambitious vision for the future through learning, discovery and public engagement. Aptly enough, music “took root” immediately in the new university community with music studies and ensembles assuming a significant presence on the campus even before the School of Music opened in 1895. THE OPPORTUNITY The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign The school’s teaching, research, and public invites nominations and applications for the engagement reflect a historic record of service to position of Director of the School of Music. The music as practiced in a wide variety of settings and university strongly encourages nominations of, as idioms. The faculty and staff bring an ambitious well as applications from, individuals traditionally portfolio of creative and scholarly accomplishment, underrepresented in the academy. and a principled commitment to the public good As the chief executive officer of the School of befitting its location within Illinois’ largest land-grant Music, the Director provides creative, effective research university. Together with an accomplished and collaborative leadership in the planning and alumni, the school’s artists, scholars, and teachers implementation of the school’s research, teaching, contribute to a growing record of sustained and public engagement missions. The Director is engagement with diverse communities of musical a visionary leader who partners with the school’s practice, from the world’s premiere performance halls faculty, students, and staff to advance creative to the most deeply embedded centers of traditional practice and scholarship; prioritize diversity, equity, and experimental musicianship. -

Programmation Jazz À Vienne De 1980 À 2019

PROGRAMMATION JAZZ À VIENNE DE 1980 À 2019 SOMMAIRE 1980 ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 1981 ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 1982 ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 1983 ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 1984 ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 1985 ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 9 1986 .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 11 1987 ......................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Notre Dame Collegiate Jazz Festival Program, 2002

Archives of the University of Notre Dame Archives of the University of Notre Dame Table of Contents Festival Schedule University of Notre Dame Collegiate Jazz Festival WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 28TH Preview Night- LaFortune Ballroom: Festival Director: 7:30 University of Notre Dame Jazz II Lauren E. Fowler University of Notre Dame Combo Assistant to the Festival Director: FRIDAY, MARCH 1ST Kim Zigich Evening Concert Block- Washington Hall: 7:30 University of Missouri-Kansas City Jazz Ensemble Festival Controller: Bobby Watson, Director Bryan Kronk 8:15 Western Michigan University Jazz Quintet Trent Kynaston, Director Festival Graphic Designer: 9:00 University of Hawaii Jazz Ensemble Elisabeth Parker Patrick Hennessey, Director 9:45 University of Alaska-Fairbanks Jazz Band Student Union Board Advisor: John Harbaugh, Director Melvin D. Adams, III 2 Festival Schedule 10:30 Western Michigan University Jazz Orchestra Trent Kynaston, Director Faculty Advisor to the Festival: 3 Welcome from the Festival Director 11:15 Judges' Jam Larry Dwyer James Carter, saxophone Cecil Bridgewater, trumpet Special thanks to: 4 A Tribute to Father George Wiskirchen, esc Rodney Whitaker, bass Paul J. Krivickas, Student Union Board Manager Jim McNeely, piano Katie Hammond, Director of Programming a Jazz Festival History John Robinson, percussion Jackie Gelzheiser, Director of Operations Gabe Brown, Director of Creativity Festival Adjudicators 7 SATURDAY, MARCH 3RD Melissa Kane, Chief Controller Clinic- Notre Dame Band Building: 12 This year's bands 2:00 Meet in main