DEVELOPMENT of MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES for MALLARD and CANVASBACK Region 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bears in Oklahoma

April 2010 Bears in Oklahoma Our speaker for the April 19 meeting of the Oklahoma City Audubon Society will be Jeremy Dixon, wildlife biologist at the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge. His presentation is titled “The Strange But True History of Bears in Oklahoma.” For many years Jeremy was a biologist in Florida where he studied the interactions between black bears and humans. His master’s research was on the Conservation Genetics of the Florida Black Bear. Jeremy moved to Lawton in 2009 to experience life out here in the middle of the continent. Our grass prairie and ancient granite mountains are a new living environment for him. However, the black bears are coming back across Oklahoma from the east presenting birders an experience with a new and large predator to which we are unaccustomed. With an education from Jeremy, hopefully we can learn how to watch the birds while not feeding the bears ourselves. Come out for bear-hugging good time at bird club and bring a friend. County Birding: Kingfisher Jimmy Woodard On March 11, the group of 7 birders entered Kingfisher County in the far southeast corner. We located several small lakes with waterfowl: Canada Geese, Gadwall, Mallard, Green- Winged Teal and Ruddy Duck. We also found an adult Bald Eagle, the first of two found during the trip. Driving the back roads, we observed Great Horned Owl, Phoebe, King- fisher, and a bunch of sparrows – Harris, White Crowned, Song, Savannah, & Lincoln’s. We visited fields along the Cimarron River southeast of Dover. Carla Brueggen & her hus- band lease fields in this area. -

Wildlife Populations in Texas

Wildlife Populations in Texas • Five big game species – White-tailed deer – Mule deer – Pronghorn – Bighorn sheep – Javelina • Fifty-seven small game species – Forty-six migratory game birds, nine upland game birds, two squirrels • Sixteen furbearer species (i.e. beaver, raccoon, fox, skunk, etc) • Approximately 900 terrestrial vertebrate nongame species • Approximately 70 species of medium to large-sized exotic mammals and birds? White-tailed Deer Deer Surveys Figure 1. Monitored deer range within the Resource Management Units (RMU) of Texas. 31 29 30 26 22 18 25 27 17 16 24 21 15 02 20 28 23 19 14 03 05 06 13 04 07 11 12 Ecoregion RMU Area (Ha) 08 Blackland Prairie 20 731,745 21 367,820 Cross Timbers 22 771,971 23 1,430,907 24 1,080,818 25 1,552,348 Eastern Rolling Plains 26 564,404 27 1,162,939 Ecoregion RMU Area (Ha) 29 1,091,385 Post Oak Savannah 11 690,618 Edwards Plateau 4 1,308,326 12 475,323 5 2,807,841 18 1,290,491 6 583,685 19 2,528,747 7 1,909,010 South Texas Plains 8 5,255,676 28 1,246,008 Southern High Plains 2 810,505 Pineywoods 13 949,342 TransPecos 3 693,080 14 1,755,050 Western Rolling Plains 30 4,223,231 15 862,622 31 1,622,158 16 1,056,147 39,557,788 Total 17 735,592 Figure 2. Distribution of White-tailed Deer by Ecological Area 2013 Survey Period 53.77% 11.09% 6.60% 10.70% 5.89% 5.71% 0.26% 1.23% 4.75% Edwards Plateau Cross Timbers Western Rolling Plains Post Oak Savannah South Texas Plains Pineywoods Eastern Rolling Plains Trans Pecos Southern High Plains Figure 3. -

Canvasback Aythya Valisineria

Canvasback Aythya valisineria Class: Aves Order: Anseriformes Family: Anatidae Characteristics: A large diving duck, in fact the largest in its genus, the canvasback weighs about 2.5-3 pounds. The male has a chestnut-red head, red eyes, light white-grey body and blackish breast and tail. The female has a lighter brown head and neck that gets progressively darker brown toward the back of the body. Both sexes have a blackish bill and bluish-grey legs and feet. Range & Habitat: Behavior: Breeds in prairie potholes and A wary bird that is very swift in flight. They prefer to dive in shallow water winters on ocean bays to feed and will also feed on the water surface (Audubon). Reproduction: Several males will court and display to one female. Once a female chooses the male, they will form a monogamous bond through breeding season. They build a floating nest in stands of dense vegetation above shallow water and lay 7-12 olive-grey eggs. Often redheads will lay their eggs in canvasback nests which will result in canvasbacks laying fewer eggs. The female incubates the eggs which hatch after 23-28 days. The young feed themselves and mom leads them to water within hours of hatching. Lifespan: up to 20 years in Diet: captivity, 10 years in the wild. Wild: Seeds, plant material, snails and insect larvae, they dive to eat the roots and bases of plants Special Adaptations: They go Zoo: Scratch grains, greens, waterfowl pellets from freshwater marshes in summer to saltwater ocean bays in Conservation: winter. Some say the populations are decreasing while others say they are increasing due to habitat restoration and the ban on lead shot. -

Canvasback and Lesser Scaup Activities and Habitat-Use on Pool 19, Upper Mississippi River

Transactions of the Illinois State Academy of Science (1993), Volume 86, 1 and 2, pp. 33 - 45 Canvasback and Lesser Scaup Activities and Habitat-Use on Pool 19, Upper Mississippi River David M. Day1, Richard V. Anderson and Michael A. Romano Department of Biological Sciences Western Illinois University Macomb, IL 61455 1Current address: Illinois Department of Conservation Streams Program Aledo, IL 61231 ABSTRACT Behavior and habitat use of canvasback (Aythya valisineria) and lesser scaup (Aythya affinis) were assessed on Pool 19 of the Upper Mississippi River during the spring and fall of 1982 and the spring of 1983. Ducks were frequently observed in three sections of the study area; on the Illinois side of the river from Hamilton to Nauvoo; between Montrose and Niota; and in spring near Dallas City. Resting behavior was most prevalent, followed by diving (feeding) and loafing (sleeping). Lesser scaup dove more and spent less time loafing than canvasbacks. For all three seasons, within nonvegetated habitat, no significant seasonal or behavioral differences were found between male and female canvasbacks, but significant differences were found between the sexes of lesser scaup. Differences in activities between male and female lesser scaup did not persist when fall observations were excluded, suggesting seasonal differences in use of Pool 19. No significant seasonal or behavioral differences between species were observed in ducks using submergent vegetation during the spring periods. Activity patterns for both species, during the combined spring periods, were significantly different between submergent vegetation and nonvegetated areas. It appears these differences were due largely to changes in the distribution of diving and loafing activities between habitats. -

Derivation of Non-Breeding Duck

North American Waterfowl Management Plan Science Support Team Technical Report No. 2019–01 Derivation of Regional, Non-breeding Duck Population Abundance Objectives to Inform Conservation Planning in North America — 2019 Revision Kathy K. Fleming U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Migratory Bird Management Michael K. Mitchell Ducks Unlimited, Inc. Southern Regional Office Michael G. Brasher Ducks Unlimited, Inc., Gulf Coast Joint Venture John M. Coluccy Ducks Unlimited, Inc., Great Lakes and Atlantic Regional Office J. Dale James Ducks Unlimited, Inc. Southern Regional Office Mark J. Petrie Ducks Unlimited, Inc., Western Regional Office, Pacific Coast Joint Venture Dale D. Humburg Ducks Unlimited, Inc., National Headquarters Gregory J. Soulliere U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Upper Mississippi / Great Lakes Joint Venture ABSTRACT During the early 2000s, a methodology was developed to derive regional non-breeding population abundance objectives from continental abundance estimates (M. Koneff, USFWS, unpublished data). This information was foundational to North American Waterfowl Management Plan (NAWMP) Joint Venture (JV) habitat conservation planning and implementation for non-breeding waterfowl, especially wintering ducks. The 2012 NAWMP Revision and its amended population objectives motivated JVs to begin updating their waterfowl implementation plans. Fleming et al. (2017) revisited the initial work to derive non- breeding abundance objectives and developed an updated approach. Although Fleming et al. (2017) made use of the least biased and most geographically consistent datasets, they identified outstanding issues to be resolved before the derivation technique could be effectively applied across all regions of North America. We updated the work of Fleming et al. (2017) by addressing 3 of those issues. -

2019 Waterfowl Population Status Survey

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Waterfowl Population Status, 2019 Waterfowl Population Status, 2019 August 19, 2019 In the United States the process of establishing hunting regulations for waterfowl is conducted annually. This process involves a number of scheduled meetings in which information regarding the status of waterfowl is presented to individuals within the agencies responsible for setting hunting regulations. In addition, the proposed regulations are published in the Federal Register to allow public comment. This report includes the most current breeding population and production information available for waterfowl in North America and is a result of cooperative eforts by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), the Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS), various state and provincial conservation agencies, and private conservation organizations. In addition to providing current information on the status of populations, this report is intended to aid the development of waterfowl harvest regulations in the United States for the 2020–2021 hunting season. i Acknowledgments Waterfowl Population and Habitat Information: The information contained in this report is the result of the eforts of numerous individuals and organizations. Principal contributors include the Canadian Wildlife Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, state wildlife conservation agencies, provincial conservation agencies from Canada, and Direcci´on General de Conservaci´on Ecol´ogica de los Recursos Naturales, Mexico. In addition, several conservation organizations, other state and federal agencies, universities, and private individuals provided information or cooperated in survey activities. Appendix A.1 provides a list of individuals responsible for the collection and compilation of data for the “Status of Ducks” section of this report. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

2004 Proposed Rule Making Public Safety Cougar Removals

CR-102 (June 2004) PROPOSED RULE MAKING (Implements RCW 34.05.320) Do NOT use for expedited rule making Agency: Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Preproposal Statement of Inquiry was filed as WSR 11-06-058 and WSR 11- Original Notice 10-083 ; or Supplemental Notice to WSR Expedited Rule Making--Proposed notice was filed as WSR ; or Continuance of WSR Proposal is exempt under RCW 34.05.310(4). Title of rule and other identifying information: (Describe Subject) WAC 232-12-243, Public safety cougar removals. WAC 232-28-272, 2009 Black bear and 2009-2010, 2010-2011, and 2011-2012 cougar hunting seasons and regulations. WAC 232-28-287, 2009-2010, 2010-2011, and 2011-2012 Cougar permit seasons and regulations. WAC 232-28-435, 2011-12 Migratory waterfowl seasons and regulations. Hearing location(s): Submit written comments to: Natural Resources Building, Conference Room 172 Name: Wildlife Program Commission Meeting Public Comments 1111 Washington Street SE Address: 600 Capitol Way North, Olympia WA 98501-1091 Olympia, Washington 98504 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (360) 902-2162 by (date) Wednesday, July 13, 2011 Date: August 5-6, 2011 Time: 8:30 a.m. Assistance for persons with disabilities: Contact Susan Yeager by July 29, 2011 Date of intended adoption: August 5-6, 2011 TTY (800) 833-6388 or (360) 902-2267 (Note: This is NOT the effective date) Purpose of the proposal and its anticipated effects, including any changes in existing rules: See Attachment A Reasons supporting proposal: See Attachment A Statutory authority for adoption: -

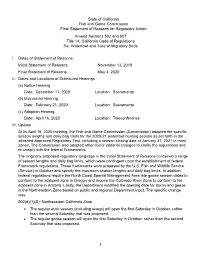

Final Statement of Reasons for Regulatory Action Amend Sections 502 and 507 Title 14, California Code of Regulations Re: Waterfowl and Take of Migratory Birds

State of California Fish and Game Commission Final Statement of Reasons for Regulatory Action Amend Sections 502 and 507 Title 14, California Code of Regulations Re: Waterfowl and Take of Migratory Birds I. Dates of Statement of Reasons: Initial Statement of Reasons: November 13, 2019 Final Statement of Reasons: May 4, 2020 II. Dates and Locations of Scheduled Hearings (a) Notice Hearing Date: December 11, 2020 Location: Sacramento (b) Discussion Hearing Date: February 21, 2020 Location: Sacramento (c) Adoption Hearing Date: April 16, 2020 Location: Teleconference III. Update At its April 16, 2020 meeting, the Fish and Game Commission (Commission) adopted the specific season lengths and daily bag limits for the 2020-21 waterfowl hunting season as set forth in the attached Approved Regulatory Text, including a season closing date of January 31, 2021 in most zones. The Commission also adopted other minor editorial changes to clarify the regulations and to comply with the federal Frameworks. The originally proposed regulatory language in the Initial Statement of Reasons contained a range of season lengths and daily bag limits, which were contingent upon the establishment of federal Framework regulations. These frameworks were proposed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) in October and specify the maximum season lengths and daily bag limits. In addition, federal regulations require the North Coast Special Management Area late goose season dates to conform to the adjacent zone in Oregon and require the Colorado River Zone to conform to the adjacent zone in Arizona. Lastly, the Department modified the opening date for ducks and geese in the Northeastern Zone based on public and regional Department input. -

Valentine National Wildlife Refuge: Wildlife List

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Valentine National Wildlife Refuge Wildlife List Wildlife Abounds Valentine National Wildlife Refuge Hackberry and Look for ducks and geese, especially in the Native (NWR), located 25 miles south of Pelican Lakes during the spring and fall. Watch for Prairie the town of Valentine, Nebraska, is pintail, mallard, ruddy, canvasback, 71,774 acres in size and was established and many more ducks. Take a walk in 1935 as a Refuge and breeding on the nature trail up to the old fire grounds for migratory birds and tower on the west end of Hackberry other wildlife. In fact, most of the Lake for a view of the Sandhills and wildlife present in historical times a look at grassland sparrows. This goose, are still present on the Refuge designed by J.N. today. Numerous wetlands, lakes, Duck Lake Look in the trees around the boat “Ding” Darling, wet meadows, and large expanses of ramp for they are an oasis for has become the native prairie attract a wide variety songbirds. Watch for warblers, blue symbol of the of wildlife. This brochure lists and black-headed grosbeaks, Lazuli National Wildlife 289 species of birds, 41 species of buntings, eastern bluebirds, and Refuge System. mammals, 16 species of reptiles, and many more. six species of amphibians that have been recorded on the Refuge. Check-list Key Sp Spring March – May S Summer June – August May, September, and October offer F Fall September – November good opportunities for observing a W Winter December – February variety of migratory birds. Spring migrants, including waterfowl and c common – present in large warblers, are most numerous in May. -

Comparing Two Genetic Markers Used in the Identification of Diving

Comparing two genetic markers used in the identification of diving ducks (Aythyinae) involved in birdstrikes Damani Eubanks, Carla Dove Ph.D, Faridah Dahlan, Sergei Drovetski Ph.D Abstract Results Knowing the species of birds involved in damaging collisions with U.S. military and civil aircraft (birdstrikes) is For our phylogenetic reconstruction we used 25 (16 new and 9 from GenBank) ND2 sequences and 51 (17 new and paramount to understanding and preventing human-wildlife conflicts in this field. The Feather Identification Lab, 34 from GenBank/BoLD) CO1 sequences. Although we were not able to sequence 3 samples for ND2 and for 2 Smithsonian Institution, identifies over 9,000 birdstrike cases each year using feather morphology and DNA samples for CO1, this indicates similar efficiency of ND2 and CO1 primers. barcoding. While the DNA barcode marker (CO1) is successful at identifying many species of birds, it falls short Genetic distances between closely related species in the ND2 tree were 1.8 - 5.3 times greater than those in the CO1 in species that are very closely related or hybridize frequently. This project tested the effectiveness of two tree (Fig. 1; Table 1). When number of segregating sites is considered, the differences are even greater due to the mitochondrial genetic markers, cytochrome oxidase 1 (CO1) and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (ND2) used for differences in sequence length of the two markers. identifying species of waterfowl within the genus Aythya. Because these diving ducks are commonly involved in Both the differences in evolutionary rate and the sequence length between the two loci had a strong effect on posterior damaging birdstrikes, the most reliable method of DNA identification is needed for species designation of probability of monophyly of conspecific haplotypes. -

Reintroduction of Greater Prairie Chickens Using Egg

Reintroduction of greater prairie chickens using egg substitution on Arrowwood National Wildlife Refuge, North Dakota by Howard Raymond Burt A thesis submited in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Fish and Wildlife Management Montana State University © Copyright by Howard Raymond Burt (1991) Abstract: Reintroduction of greater prairie chickens (Tympanuchus cupido pinnatus) to Arrowwood National Wildlife Refuge, North Dakota, was attempted in the spring and summer of 1988 and 1989. The method entailed substituting prairie chicken eggs into sharp-tailed grouse (Tympanuchus phansianellis Jamesi) nests. Thirty-five sharp-tailed grouse hens were captured on dancing grounds or nests and instrumented with radio transmitters. Thirty-five sharptail nests were located by telemetry or cable-chain drag. Most (54%) nests were located in vegetation containing a combination of brush and grass. Success of all nesting sharptail hens was low (48%), with predators destroying 37% of the nests. Twenty-six sharptailed grouse and 1 ring-necked pheasant (Phasianus colchi-cus) nests were provided with 523 prairie chicken eggs. Fifteen nests were provided with unincubated prairie chicken eggs and 12 were provided with prairie chicken eggs incubated at least 20 days. Nests provided with unincubated prairie chicken eggs had a lower (33%) nest success than nests provided with incubated eggs (92%). Hatchability of unincubated prairie chicken eggs (43%) was significantly lower than for incubated eggs (79%). Only 2% of 102 prairie chicken chicks that left the nest with radioed sharptail hens survived until the end of the field seasons. Sharp-tailed grouse with prairie chicken broods were located most often (61%) in vegetation types with a combination of brush and grass, and appeared to select brood habitat which may have been less than optimum for prairie chicken chicks.