Irish Public Sector Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF(All Devices)

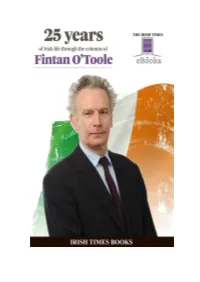

Published by: The Irish Times Limited (Irish Times Books) © The Irish Times 2014. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of The Irish Times Limited, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographic rights organisation or as expressly permitted by law. Contents Watching from a window as we all stay the same ................................................................ 4 Emigration- an Irish guarantor of continuity ........................................................................ 7 Completing a transaction called Ireland ................................................................................ 9 In the land of wink and nod ................................................................................................. 13 Rhetoric, reality and the proper Charlie .............................................................................. 16 The rise to becoming a beggar on horseback ...................................................................... 19 The real spiritual home of Fianna Fáil ................................................................................ 21 Electorate gives ethics the cold shoulders ........................................................................... 24 Corruption well known – and nothing was done ................................................................ 26 Questions the IRA is happy to ignore ................................................................................ -

OIR : Core Book 53

TUARASCÁIL ón gComhchoiste Fiosrúcháin i dtaobh na Géarchéime Baincéireachta An tAcht um Thithe an Oireachtais (Fiosrúcháin, Pribhléidí agus Nósanna Imeachta), 2013 REPORT of the Joint Committee of Inquiry into the Banking Crisis Houses of the Oireachtas (Inquiries, Privileges and Procedures) Act, 2013 Volume 1: Report Volume 2: Inquiry Framework Volume 3: Evidence Oireachtas OIR : Core Book 53 January 2016 Table of contents – by line of inquiry R5: Clarity and effectiveness of the Government and Oireachtas oversight and role R5d: Appropriateness of relationships between Government , the Oireachtas , banking sector and the property sector Bates Number Description Page [Relevant Pages] DOT00716 018 Letter from Alan Cooke Chief Executive Officer IAVI (Extract) 2-3 [001-002] DOT00727 Letter from Sean McEniff Tyrconnell Group, July 2000 (Extract) 4-6 [001-003] DOT00728 Letter from Taoiseach to Sean McEniff 25 July 2000 (Extract) 7-8 [001-002] Memo to Taoiseach and Letter from Hooke McDonald June 2000 DOT00729 9 (Extract) [001] Fax message from Taoiseach to DoE enclosing letter from Ken DOT00730 10-13 McDonald [001-004] DOT00736 Minutes of Taoiseach’s Meeting with Ken McDonald 20 09 2000 14 [001] DOT00745 Letter from O’Flynn, 27th April, 2004 15 [001] DOT00749 Briefing Note for meeting with O’Flynn 08 July 04 (Extract) 16 [001] DOT00750 Letter from Noel O’Callaghan to Dept of Taoiseach on planning 17-19 [001-003] DOT00751 52 Letter and enclosure from O’Flynn Construction (Extract) 20-23 [001-004] PUB00333 Interview with Brian Dobson 26 Sep -

Here's the Report Itself

REPORT of the TRIBUNAL OF INQUIRY (DUNNES PAYMENTS) BAILE ATHA CLIATH ARNA FHOILS1U AG OIFIG AN tSOLATHAIR Le ceannach direaeh on OIFIC. DHIOLTA FOILSEACHAN RIALTAIS. TEACH SUN ALLIANCE, SRAlD THEACH LAIGHEAN, BAILE ATHA CLIATH 2. no trid an bpost o FOILSEACHAIN RIALTAIS. AN RANNOG POST-TRACHTA, 4 - 5 BOTHAR FHEARCHAIR. BAILE ATHA CLIATH 2. (Teil: 01 - 6613111 — fo-h'ne 4040/4045; Fax: 01 - 4752760) no iri aon dioltoir leabhar. DUBLIN PUBLISHED BY THE STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased directly from Hie GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS SALE OFFICE. SUN ALLIANCE HOUSE, MOLESWORTH STREET, DUBLIN 2, or by mail order from GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. POSTAL TRADE SECTION. 4 - 5 H A R C O U R T R O A D , DUBLIN 2, (Tel: 01 - 6613111 — ext. 4040/4045: Fax: 01 - 4752760) or through any bookseller. Tribunal of Inquiry Tribunal Office Appointed by instrument of State Apartments. An Taoiseach The Upper Yard, dated the 7th day o f February 1997 Dublin Castle, Sole Member Dublin 2. The Honourable Mr. Justice Brian McCracken Tel: 6705666 Fax: 6705490 © Government of Ireland 1997 25 August 1997 Mr. Bertie Ahern TD Taoiseach Government Buildings Upper Merrion Street D ublin 2 Dear Taoiseach, I enclose herewith my Report as Sole Member of the Tribunal appointed by Order made on the 7th day of February 1997 by the then Taoiseach Mr John Bruton, pursuant to resolutions of Dail Eireann and Seanad Eireann each passed on the 6th day of February 1997 to enquire into payments made to certain politicians or con nected persons or political parties by Dunnes Holding Company or any associated enterprises and/or by Mr. -

Report of the Tribunal of Inquiry Into Payments to Politicians and Related Matters

Report of the Tribunal of Inquiry into Payments to Politicians and Related Matters Part I BAILE A´ THA CLIATH ARNA FHOILSIU´ AG OIFIG AN tSOLA´ THAIR Le ceannach dı´reach o´n OIFIG DHI´OLTA FOILSEACHA´ N RIALTAIS, TEACH SUN ALLIANCE, SRA´ ID THEACH LAIGHEAN, BAILE A´ THA CLIATH 2, no´ trı´d an bpost o´ FOILSEACHA´ IN RIALTAIS, AN RANNO´ G POST-TRA´ CHTA, 51 FAICHE STIABHNA, BAILE A´ THA CLIATH 2, (Teil: 01 - 6476834/35/36/37; Fax: 01 - 6476843) no´ trı´ aon dı´olto´ir leabhar. —————— DUBLIN PUBLISHED BY THE STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased directly from the GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS SALE OFFICE, SUN ALLIANCE HOUSE, MOLESWORTH STREET, DUBLIN 2, or by mail order from GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS, POSTAL TRADE SECTION, 51 ST. STEPHEN’S GREEN, DUBLIN 2, (Tel: 01 - 6476834/35/36/37; Fax: 01 - 6476843) or through any bookseller. —————— (Prn. A6/1834) \5.00 Government of Ireland 2006 ISBN 0-7557-7459-0 Wt. —. 1,500. 12/06. Cahill. (M96408). G.Spl. Letters 14/12/2006 07:56 Page 2 Letters 14/12/2006 07:56 Page 1 REPORT OF THE TRIBUNAL ON PAYMENTS TO POLITICIANS AND RELATED MATTERS — PART 1 PREFACE In a long running Tribunal, it is inevitable that an amount of turnover in the personnel attached to it will occur, hence the list of persons who gave assistance at different times is less short than the total number involved at any one time, which ranged between twelve and fifteen. Apart from those mentioned here, there was a small number of lawyers whose duties primarily related to the matters that will be addressed in the Second Part of the Report in 2007, and it is preferable that their contributions should be acknowledged at that stage. -

Issue July 2000

Contents GazetteLawSociety Regulars Cover Story When saying sorry isn’t enough President’s message 3 14 The story of children abused in industrial schools touched the hearts of the Irish people. The taoiseach even apologised to the victims on News 4 behalf of the state. But, as Karen O’Connor points out, the shine of sincerity will fade from that apology if the question of liability Viewpoint 10 is not addressed Letters 12 Tech trends 30 A basic guide to discovery Briefing 33 18 Discovery is a central part of litigation, but some practitioners regard it with Practice notes 33 trepidation because it can often involve Legislation sifting through reams of documents. update 37 Eoin Dee discusses the essential Personal injury elements of discovery judgments 38 FirstLaw update 42 Eurlegal 47 The new meaning of master 24 and apprentice People and All solicitors have experience of apprenticeships, and places 51 their opinions can vary from fond memories of valuable learning Apprentices’ page 53 and personal development to flashbacks of disastrous lost opportunities. John Connellan looks at the relationship between Professional master and apprentice information 54 COVER PHOTO: [email protected] Equal measures 26 The sweeping provisions of the Employment Equality Act, 1998 mean that you could be advising a growing number of your clients on their recruitment practices. Michelle Nì Longàin explains what employers must do to ensure that their procedures comply with the legislation Editor: Conal O’Boyle MA. Assistant Editor: Maria Behan. Designer: Nuala Redmond. Editorial Secretaries: Catherine Kearney, Louise Rose. Advertising: Seán Ó hOisín, 10 Arran Road, Dublin 9, tel/fax: 837 5018, mobile: 086 8117116, e-mail: [email protected].