Edward Gresham, Copernican Cosmology, and Planetary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Persian-Toledan Astronomical Connection and the European Renaissance

Academia Europaea 19th Annual Conference in cooperation with: Sociedad Estatal de Conmemoraciones Culturales, Ministerio de Cultura (Spain) “The Dialogue of Three Cultures and our European Heritage” (Toledo Crucible of the Culture and the Dawn of the Renaissance) 2 - 5 September 2007, Toledo, Spain Chair, Organizing Committee: Prof. Manuel G. Velarde The Persian-Toledan Astronomical Connection and the European Renaissance M. Heydari-Malayeri Paris Observatory Summary This paper aims at presenting a brief overview of astronomical exchanges between the Eastern and Western parts of the Islamic world from the 8th to 14th century. These cultural interactions were in fact vaster involving Persian, Indian, Greek, and Chinese traditions. I will particularly focus on some interesting relations between the Persian astronomical heritage and the Andalusian (Spanish) achievements in that period. After a brief introduction dealing mainly with a couple of terminological remarks, I will present a glimpse of the historical context in which Muslim science developed. In Section 3, the origins of Muslim astronomy will be briefly examined. Section 4 will be concerned with Khwârizmi, the Persian astronomer/mathematician who wrote the first major astronomical work in the Muslim world. His influence on later Andalusian astronomy will be looked into in Section 5. Andalusian astronomy flourished in the 11th century, as will be studied in Section 6. Among its major achievements were the Toledan Tables and the Alfonsine Tables, which will be presented in Section 7. The Tables had a major position in European astronomy until the advent of Copernicus in the 16th century. Since Ptolemy’s models were not satisfactory, Muslim astronomers tried to improve them, as we will see in Section 8. -

A History of Astronomy, Astrophysics and Cosmology - Malcolm Longair

ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS - A History of Astronomy, Astrophysics and Cosmology - Malcolm Longair A HISTORY OF ASTRONOMY, ASTROPHYSICS AND COSMOLOGY Malcolm Longair Cavendish Laboratory, University of Cambridge, JJ Thomson Avenue, Cambridge CB3 0HE Keywords: History, Astronomy, Astrophysics, Cosmology, Telescopes, Astronomical Technology, Electromagnetic Spectrum, Ancient Astronomy, Copernican Revolution, Stars and Stellar Evolution, Interstellar Medium, Galaxies, Clusters of Galaxies, Large- scale Structure of the Universe, Active Galaxies, General Relativity, Black Holes, Classical Cosmology, Cosmological Models, Cosmological Evolution, Origin of Galaxies, Very Early Universe Contents 1. Introduction 2. Prehistoric, Ancient and Mediaeval Astronomy up to the Time of Copernicus 3. The Copernican, Galilean and Newtonian Revolutions 4. From Astronomy to Astrophysics – the Development of Astronomical Techniques in the 19th Century 5. The Classification of the Stars – the Harvard Spectral Sequence 6. Stellar Structure and Evolution to 1939 7. The Galaxy and the Nature of the Spiral Nebulae 8. The Origins of Astrophysical Cosmology – Einstein, Friedman, Hubble, Lemaître, Eddington 9. The Opening Up of the Electromagnetic Spectrum and the New Astronomies 10. Stellar Evolution after 1945 11. The Interstellar Medium 12. Galaxies, Clusters Of Galaxies and the Large Scale Structure of the Universe 13. Active Galaxies, General Relativity and Black Holes 14. Classical Cosmology since 1945 15. The Evolution of Galaxies and Active Galaxies with Cosmic Epoch 16. The Origin of Galaxies and the Large-Scale Structure of The Universe 17. The VeryUNESCO Early Universe – EOLSS Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical SketchSAMPLE CHAPTERS Summary This chapter describes the history of the development of astronomy, astrophysics and cosmology from the earliest times to the first decade of the 21st century. -

Copernicus and Tycho Brahe

THE NEWTONIAN REVOLUTION – Part One Philosophy 167: Science Before Newton’s Principia Class 2 16th Century Astronomy: Copernicus and Tycho Brahe September 9, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. The Copernican Revolution .................................................................................................................. 1 A. Ptolemaic Astronomy: e.g. Longitudes of Mars ................................................................... 1 B. A Problem Raised for Philosophy of Science ....................................................................... 2 C. Background: 13 Centuries of Ptolemaic Astronomy ............................................................. 4 D. 15th Century Planetary Astronomy: Regiomantanus ............................................................. 5 E. Nicolaus Copernicus: A Brief Biography .............................................................................. 6 F. Copernicus and Ibn al-Shāţir (d. 1375) ……………………………………………………. 7 G. The Many Different Copernican Revolutions ........................................................................ 9 H. Some Comments on Kuhn’s View of Science ……………………………………………... 10 II. De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelstium (1543) ..................................................................................... 11 A. From Basic Ptolemaic to Basic Copernican ........................................................................... 11 B. A New Result: Relative Orbital Radii ................................................................................... 12 C. Orbital -

Copernicus and His Revolutions

Copernicus and his Revolutions Produced for the Cosmology and Cultures Project of the OBU Planetarium by Kerry Magruder August, 2005 2 Credits Written & Produced by: Kerry Magruder Narrator: Candace Magruder Copernicus: Kerry Magruder Cardinal Schönberg: Phil Kemp Andreas Osiander: J Harvey C. S. Lewis: Phil Kemp Johann Kepler: J Harvey Book Images courtesy: History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries Photographs and travel slides courtesy: Duane H.D. Roller Archive, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries Digital photography by: Hannah Magruder Soundtrack composed and produced by: Eric Barfield Special thanks to... Peter Barker, Bernie Goldstein, Katherine Tredwell, Dennis Danielson, Mike Keas, JoAnn Palmeri, Hannah Magruder, Rachel Magruder, Susanna Magruder, Candace Magruder Produced with a grant from the American Council of Learned Societies 3 1. Contents 1. Contents________________________________________________3 2. Introduction _____________________________________________4 A. Summary ____________________________________________4 B. Synopsis ____________________________________________5 C. Instructor Notes_______________________________________7 3. Before the Show _________________________________________9 A. Vocabulary and Definitions _____________________________9 B. Pre-Test ____________________________________________10 4. Production Script________________________________________11 A. Production Notes_____________________________________11 B. Theater Preparation___________________________________13 -

Theme 4: from the Greeks to the Renaissance: the Earth in Space

Theme 4: From the Greeks to the Renaissance: the Earth in Space 4.1 Greek Astronomy Unlike the Babylonian astronomers, who developed algorithms to fit the astronomical data they recorded but made no attempt to construct a real model of the solar system, the Greeks were inveterate model builders. Some of their models—for example, the Pythagorean idea that the Earth orbits a celestial fire, which is not, as might be expected, the Sun, but instead is some metaphysical body concealed from us by a dark “counter-Earth” which always lies between us and the fire—were neither clearly motivated nor obviously testable. However, others were more recognisably “scientific” in the modern sense: they were motivated by the desire to describe observed phenomena, and were discarded or modified when they failed to provide good descriptions. In this sense, Greek astronomy marks the birth of astronomy as a true scientific discipline. The challenges to any potential model of the movement of the Sun, Moon and planets are as follows: • Neither the Sun nor the Moon moves across the night sky with uniform angular velocity. The Babylonians recognised this, and allowed for the variation in their mathematical des- criptions of these quantities. The Greeks wanted a physical picture which would account for the variation. • The seasons are not of uniform length. The Greeks defined the seasons in the standard astronomical sense, delimited by equinoxes and solstices, and realised quite early (Euctemon, around 430 BC) that these were not all the same length. This is, of course, related to the non-uniform motion of the Sun mentioned above. -

The Impact of Copernicanism on Judicial Astrology at the English Court, 1543-1660 ______

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 1-2011 'In So Many Ways Do the Planets Bear Witness': The mpI act of Copernicanism on Judicial Astrology at the English Court, 1543-1660 Justin Dohoney Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Dohoney, Justin, "'In So Many Ways Do the Planets Bear Witness': The mpI act of Copernicanism on Judicial Astrology at the English Court, 1543-1660" (2011). All Theses. 1143. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1143 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "IN SO MANY WAYS DO THE PLANETS BEAR WITNESS": THE IMPACT OF COPERNICANISM ON JUDICIAL ASTROLOGY AT THE ENGLISH COURT, 1543-1660 _____________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts History _______________________________________________________ by Justin Robert Dohoney August 2011 _______________________________________________________ Accepted by: Pamela Mack, Committee Chair Alan Grubb Megan Taylor-Shockley Caroline Dunn ABSTRACT The traditional historiography of science from the late-nineteenth through the mid-twentieth centuries has broadly claimed that the Copernican revolution in astronomy irrevocably damaged the practice of judicial astrology. However, evidence to the contrary suggests that judicial astrology not only continued but actually expanded during the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. During this time period, judicial astrologers accomplished this by appropriating contemporary science and mathematics. -

1 David Gans on the Gregorian Reform, Modern Astronomy, and The

1 David Gans on the Gregorian reform, modern astronomy, and the Jewish calendar If we are to identify a uniting thread, or a common denominator, between in David Gans’ diverse works, – history on the one hand, and astronomy on the other – this must be an interest in the measurement of time. David Gans (1541-1613) was a leading Jewish historiographer and astronomer of the early modern period. Born in Lippstadt, he received a rabbinic education in Cracow under R. Moses Isserles, and in Prague, where he spent most of his life, under R. Loew b. Betzalel (the Maharal); but he also immersed himself in the study of history, mathematics, and astronomy. Both his major works, Tsemaḥ David (a Jewish and world chronography) and Neḥmad ve-Naim (a handbook of astronomy), assume in very different ways a range of notions about chronology, calendars, and the flow of time. Gans also wrote a specific treatise on the Jewish calendar, entitled Maor ha-Qaton (‘the smaller luminary’, i.e. the moon – Gen. 1:16); but unfortunately this work is lost. Nevertheless, a sufficient number of references are made to calendar and chronology in the works that are extant to convey his views on the Jewish calendar and, in particular, the Jewish calendar’s significance for the study of astronomy and its relationship with its Christian counterpart.1 By the late 16th century, when Gans was writing, there existed a rich tradition of scholarship on the Jewish calendar for him to draw on. The early 12th century had witnessed an eruption of monographic writing on the Jewish calendar, with books later to be known under the standard title ‘Sefer ha-Ibbur’ (‘Book of the intercalation’ or ‘calendar’), authored by Abraham b. -

Edition Open Sources Sources 11

Edition Open Sources Sources 11 Pietro Daniel Omodeo and Jürgen Renn: Astronomy In: Pietro Daniel Omodeo and Jürgen Renn (ed.): Science in Court Society : Giovan Bat- tista Benedetti’s Diversarum speculationum mathematicarum et physicarum liber (Turin, 1585) Online version at http://edition-open-sources.org/sources/11/ ISBN 978-3-945561-16-4 First published 2019 by Edition Open Access, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science under Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 Germany Licence. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/de/ Printed and distributed by: PRO BUSINESS digital printing Deutschland GmbH, Berlin http://www.book-on-demand.de/node/25750 The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; de- tailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de Chapter 6 Astronomy 6.1 Benedetti as an Astronomer Benedetti’s astronomical considerations are not systematic. They are scattered throughout the volume in different sections. In spite of the difficulty of ordering them and obtaining an overview, they were very much appreciated among his contemporaries. Apart from Kepler’s eulogy of Benedetti’s ingenuity, the broad European success of the astronomical parts of this work is documented in other references. A few years after the publication of the Diversae spaeculationes, Brahe must have had a copy of it in Denmark, as he quoted it extensively and accurately on two occasions. In his correspondence with Landgrave William IV and the Hesse-Kassel court mathematician Christopher Rothmann, he referred to Benedetti’s observation of the light of Venus reflected on the part of the lunar disc not presently enlightened by the sun: In fact, I sometimes saw that Venus illuminated in a rather sensible manner that part of the Moon that was most distant and opposed to the Sun, although the Moon is by far more distant from Venus’s circuit than the comet. -

The Reception of the Copernican Revolution Among Provençal Humanists of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries*

The Reception of the Copernican Revolution Among Provençal Humanists of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries* Jean-Pierre Luminet Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Marseille (LAM) CNRS-UMR 7326 & Centre de Physique Théorique de Marseille (CPT) CNRS-UMR 7332 & Observatoire de Paris (LUTH) CNRS-UMR 8102 France E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We discuss the reception of Copernican astronomy by the Provençal humanists of the XVIth- XVIIth centuries, beginning with Michel de Montaigne who was the first to recognize the potential scientific and philosophical revolution represented by heliocentrism. Then we describe how, after Kepler’s Astronomia Nova of 1609 and the first telescopic observations by Galileo, it was in the south of France that the New Astronomy found its main promotors with humanists and « amateurs écairés », Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc and Pierre Gassendi. The professional astronomer Jean-Dominique Cassini, also from Provence, would later elevate the field to new heights in Paris. Introduction In the first book I set forth the entire distribution of the spheres together with the motions which I attribute to the earth, so that this book contains, as it were, the general structure of the universe. —Nicolaus Copernicus, Preface to Pope Paul III, On the Revolution of the Heavenly Spheres, 1543.1 Written over the course of many years by the Polish Catholic canon Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) and published following his death, De revolutionibus orbium cœlestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) is regarded by historians as the origin of the modern vision of the universe.2 The radical new ideas presented by Copernicus in De revolutionibus * Extended version of the article "The Provençal Humanists and Copernicus" published in Inference, vol.2 issue 4 (2017), on line at http://inference-review.com/. -

Hipparchus's Table of Chords

ApPENDIX 1 Hipparchus's Table of Chords The construction of this table is based on the facts that the chords of 60° and 90° are known, that starting from chd 8 we can calculate chd(180° - 8) as shown by Figure Al.1, and that from chd S we can calculate chd ~8. The calculation of chd is goes as follows; see Figure Al.2. Let the angle AOB be 8. Place F so that CF = CB, place D so that DOA = i8, and place E so that DE is perpendicular to AC. Then ACD = iAOD = iBOD = DCB making the triangles BCD and DCF congruent. Therefore DF = BD = DA, and so EA = iAF. But CF = CB = chd(180° - 8), so we can calculate CF, which gives us AF and EA. Triangles AED and ADC are similar; therefore ADIAE = ACIDA, which implies that AD2 = AE·AC and enables us to calculate AD. AD is chd i8. We can now find the chords of 30°, 15°, 7~0, 45°, and 22~0. This gives us the chords of 150°, 165°, etc., and eventually we have the chords of all R P chord 8 = PQ, C chord (180 - 8) = QR, QR2 = PR2 _ PQ2. FIGURE A1.l. 235 236 Appendix 1. Hipparchus's Table of Chords Ci"=:...-----""----...........~A FIGURE A1.2. multiples of 71°. The table starts: 2210 10 8 2 30° 45° 522 chd 8 1,341 1,779 2,631 3,041 We find the chords of angles not listed and angles whose chords are not listed by linear interpolation. For example, the angle whose chord is 2,852 is ( 2,852 - 2,631 1)0 . -

Lecture 13 – Kepler and Newton's Laws

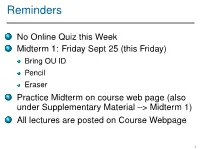

Reminders 1 No Online Quiz this Week 2 Midterm 1: Friday Sept 25 (this Friday) Bring OU ID Pencil Eraser 3 Practice Midterm on course web page (also under Supplementary Material –> Midterm 1) 4 All lectures are posted on Course Webpage 1 Lecture 13 – Kepler and Newton’s Laws 2 Aristotle 3 Aristotle’s Teaching Earth is center of the universe. Gravity is due to the fact that things want to move towards the center of the universe. Heavy things move faster than light things. Earth is corruptible, things change on it. Heavens are perfect and unchanging. Knew Earth was round. 4 End of Classical Greece Ptolemy’s system and textbook Almagest (the greatest, renamed by the Arabs) remained virtually unchanged until the 13th century. With the end of classical Greece, pursuit of knowledge passed to the Arab world. (The Romans did little to further scientific knowledge) Arabs updated the tables several times, remember precession causes them to become out of date. 5 Ptolemy 6 Fly in the ointment: Retrograde Motion of Mars 7 Astronomy in the Dark Ages in 13th Century Arabs were driven out of Spain by Christians, Ptolemy’s book became more widely available in Latin. Last great adjustment of Ptolemy’s system financed by Alfonso X of Castille: Alfonsine Tables The Renaissance was beginning in Europe 8 Critics of Aristotle and Ptolemy Heraclides: A Pythagorean who explained the diurnal motion of the stars by positing an eastward axial rotation of the central earth. Nicole Oresme (14th Century A.D.) member of the Parisian nominalist school. Formulated what we now call Galilean Relativity Critics rejected due to lack of parallax How does this illustrate the workings of the scientific method? 9 Copernicus 1473-1543 Wrote De Revoluionibus Orbium Coelestium (De Reb) around 1530, not published until year of his death. -

Aftermath of Copernicanism

HPS 322 Michael J. White History of Science Fall semester, 2013 Aftermath of Copernicanism I. Andreas Osiander represents one early reaction to the Copernican heliocentric cosmology: treating it as a useful mathematical fiction. (See Kuhn, p. 187.) II. The Copernican hypothesis was also used in the development of new celestial tables (ephemerides): A. Without committing himself to the ‘truth’ or physical reality of Copernicanism, Erasmus Reinhold used the Copernican hypothesis in developing the Prutenic Tables (published in 1551, dedicated to Albert I, Duke of Prussia; ‘Prutenia’ is the Latin for ‘Prussia’). These replaced the Alfonsine Tables of 1483 (dedicated to King Alfonso X of Castile), which were based on the Ptolemaic hypothesis. B. The much more accurate Rudophine Tables of 1627, were developed by Johannes Kepler, using the Copernican hypothesis, Kepler’s postulate of elliptical planetary orbits, and logarithms. II. Calendrical reform Under the direction of Christopher Clavius, the Copernican hypothesis was used in the calendrical reform under Pope Gregory XIII in 1582, which led to the replacement of the Julian by the Gregorian calendar very quickly in Roman Catholic regions of Europe but much more slowly in Protestant and Eastern Orthodox areas. III. Initial Protestant objects of the Copernican hypothesis based (largely) on Holy Scripture. (See Kuhn, pp. 191 and following.) The Protestant doctrine of sola Scriptura leads to an increased emphasis on the literal meaning of Scripture. This is in contrast to the older, more traditional view of various levels of meaning of Holy Scripture shared by both the Jewish Rabbinical and Christian traditions: e.g. the literal, the allegorical, the tropological (or moral), the anagogical (or eschatological): “Littera gesta docet, quid credas allegoria, moralis quid agas, quo tendas anagogia” (“The literal [meaning] teaches the facts of the matter, the allegorical what you are to believe, the moral what you are to do, and the anagogical where you are to aim”)..