Discipline and Defence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Te Wairua Kōmingomingo O Te Māori = the Spiritual Whirlwind of the Māori

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. TE WAIRUA KŌMINGOMINGO O TE MĀORI THE SPIRITUAL WHIRLWIND OF THE MĀORI A thesis presented for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Māori Studies Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand Te Waaka Melbourne 2011 Abstract This thesis examines Māori spirituality reflected in the customary words Te Wairua Kōmingomingo o te Maori. Within these words Te Wairua Kōmingomingo o te Māori; the past and present creates the dialogue sources of Māori understandings of its spirituality formed as it were to the intellect of Māori land, language, and the universe. This is especially exemplified within the confinements of the marae, a place to create new ongoing spiritual synergies and evolving dialogues for Māori. The marae is the basis for meaningful cultural epistemological tikanga Māori customs and traditions which is revered. Marae throughout Aotearoa is of course the preservation of the cultural and intellectual rights of what Māori hold as mana (prestige), tapu (sacred), ihi (essence) and wehi (respect) – their tino rangatiratanga (sovereignty). This thesis therefore argues that while Christianity has taken a strong hold on Māori spirituality in the circumstances we find ourselves, never-the-less, the customary, and traditional sources of the marae continue to breath life into Māori. This thesis also points to the arrival of the Church Missionary Society which impacted greatly on Māori society and accelerated the advancement of colonisation. -

IOFFICI@ Wai 686 #T3

IOFFICI@ Wai 686 #T3 HAURAKI AND EAST WAIROA Barry Rigby A Report Commissioned by the Waitangi Tribunal April 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS page INTRODUCTION 3 Research commissions Sources Interpretation CHAPTER ONE: HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 10 Why East Wairoa? Conspiracy allegations Invasion of the Waikato Hauraki involvement The Hunua guerrilla campaign Confiscation plans and debates Imperial constraints Confiscation in action CHAPTER TWO: HAURAKI RIGHTS IN EAST WAIROA 49 The Compensation Court The Court's early operations Procedural problems Hauraki loyalists Ancestral rights and Mackay Constraining circumstances CHAPTER THREE: PROTEST 72 Limits of protest Hoete's protest Kingitanga-inspired protest Twentieth century inquiries CONCLUSION: TREATY ISSUES ARISING 83 Historical background Confiscation and compensation Confused consequences BIBLIOGRAPHY 93 LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE 1: East Wairoa confiscation area 1865 7 FIGURE 2: Invasion of the Waikato 1863 8 FIGURE 3: Compensation COUlt map of East Wairoa 1865 9 2 Introduction Research commissions This is a repOlt about Hauraki lights within the East Wairoa confiscation area. In introducing it, I will begin by summatising the terms of my research commission. This will include a discussion of the relationship between my commission and the parallel research of Gael Ferguson and Bryan Gilling. I will then discuss very brief! y the research methodology I have employed. This will include the way I have attempted to supplement documentary research with oral history. I complete the introduction with a preview of the main lines of interpretation that feature throughout the repOlt. The preparation of this report followed a scoping exercise in mid 2001. At that time I worked in parallel with Gael Ferguson. -

James Cowan : the Significance of His Journalism Vol. 1

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. James Cowan: The Significance of his Journalism Volume One A thesis presented in three volumes in fulfilment of the requirement for the award of Doctor of Philosophy at Massey University, New Zealand. Volume 1: Thesis Volume 2: Recovered Texts Volume 3: ‘The White Slave’ Critical Edition GREGORY WOOD 2019 1 Abstract This thesis argues that to understand Cowan the historian, his interest in history and his way of writing history, one must return to the roots of his writing – his journalism. Cowan’s adroit penmanship meant that his history writing existed in close parallel to his journalism. His writing style varied little between the two areas, which meant that he reached a wide group of readers regardless of their reading level or tastes. His favourite topics included travel writing and recent history, that is, history in his lifetime. For a better understanding of how and why he wrote, some key aspects of his life and career have been selected for study. These aspects include his childhood, his early journalism as a reporter for the Auckland Star, and his later journalism for Railways Magazine. Finally, his legacy is considered from the viewpoint of his colleagues and contemporaries. Cowan the journalist was the making of Cowan the historian, and to better understand the strengths of his histories one must appreciate his journalistic background. -

I Q,Ff.ICIAQ I

DUPLICATE ~ Wf\\ b~ # b-5 Iq,ff.ICIAQ I The Nineteenth-Century Native Land Court Judges: An Introductory Report JDr Bryan D. Gilling Commissioned by the Waitangi Tribunal 1994 \. CONTENTS Prefatory Comments 1 Introduction 2 - Native Land Court Judges as Civil Servants 3 The Background of the Nineteenth-Century Judges 7 - Conclusion 24 Terms of Appointment 26 - The Native/Maori Land Court 26 - The General Courts 29 - Salaries 29 - Pluralism in Appointments 30 - Conclusion 34 The Dismissals of Judges Mair, Puckey and Wilson 36 Some Issues for Further Research 40 Bibliography 42 Appendix 1: Direction Commissioning Research 43 PREFATORY COMMENTS This report is prepared in response to a direction from the Chairperson of the Waitangi Tribunal, WAI 64 Document 3.8, dated 18 November 1994. As directed, the report addresses four main issues with specific reference to the nineteenth-century judges of the Native Land Court: their professional qualifications and the extent to which they had legal training; their relationship to the civil service of the day; whether they had been recruited from the civil service and whether they returned to it after serving on the Native Land Court bench; the terms of their appointments as Native Land Court judges; the circumstances of the dismissals in 1891 of Judges Mair, Puckey and Wilson. The time frame of 40 hours allowed in the commission did not permit an extensive biography of each judge, nor an examination of the details of the political and social climate in New Zealand as it developed throughout the last third of the nineteenth century, so the discussion will neces~arily be closely circumscribed and lacking in contextual information. -

Fortifications of the New Zealand Wars

Fortifications of the New Zealand Wars Nigel Prickett In Memory Tony Walton [26 November 1952 – 6 November 2008] New Zealand archaeological sites central file-keeper New Zealand Historic Places Trust [1978–1987] Department of Conservation [1987–2008] This report is one of the last Department of Conservation archaeological contract projects in which Tony was involved and reflects his interest in historic sites of the New Zealand Wars, and so is a fitting tribute to his career. Cover: Alexandra Redoubt, near Tuakau, was established by British troops the day after General Cameron crossed the Mangatawhiri River on 12 July 1863 at the start of the Waikato War. The earthwork fortification was located to secure the right flank of the invasion route and to protect military transport to the front on the Waikato River 100 m below. The outstanding preservation is a result of the redoubt now being within an historic reserve and cemetery. See Section 3.10 in the report. Photo: Nigel Prickett, April 1992. This report is available from the departmental website in pdf form. Titles are listed in our catalogue on the website, refer www.doc.govt.nz under Publications, then Books, posters and factsheets. © Copyright May 2016, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISBN 978–0–478–15069–8 (web PDF) ISBN 978–0–478–15070–4 (hardcopy) This report was prepared for publication by the Publishing Team; editing by Sarah Wilcox and Lynette Clelland, design and layout by Lynette Clelland. Publication was approved by the Deputy Director-General, Science and Policy Group, Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. -

Archives New Zealand Register Room: 1848 Civil Secretary Inwards

Archives New Zealand Register Room: 1848 Civil Secretary Inwards Correspondence Register Reference CS 2/1 - Year/Letter number - date written - subject - (author,place) 1848/1 Jun 19 Showing that there is no land for locating the Prisoners nearer Auckland (Surveyor General, Auckland) 1848/2 Sep 07 Accepting the Office of Reviser of Land Claims Grants (William Fox, Nelson) 1848/3 Aug 28 Applying for the appointment of Colonial Surgeon at Auckland (James F. Wilson, Nelson) 1848/4 Aug 19 Extract from the Minutes of … Co. (Clerk of Council, Wellington) 1848/5 Oct 09 Voucher of Customs Revenue for week ending October 7th, 1848 (Collector of Customs, Auckland) 1848/6 Jul 25 Abstract of cases disposed of in Resident Magistrate’s Court for quarter ending June 30, 1848 (Resident Magistrate, Wellington) 1848/7 Aug 18 Requesting His Excellency the Governor to visit the Hospital (Colonial Surgeon, Wellington) 1848/8 Jan 24 Introducing Mr Borlase (Francis J. He…, Fredesly near Bodmin, Cornwall) 1848/9a May 20 In connection with No.6 – July 25, 1848 (Resident Magistrate, Wellington) 1848/9b Jul 10 In connection with No.6 – July 25, 1848(Resident Magistrate, Wellington) 1848/10 Oct 10 Applying for employment as Gardener (Daniel Anderson, Auckland) 1848/11 Aug 22 Applying for employment (Chauncy H. Townsend, Wellington) 1848/12 Sep 12 Memorial for Representative Government (People of Wellington, Wellington) 1848/13 Aug 21 Acknowledging the receipt of … Min. Ex. Co. (Captain E. Stanley RN, Wellington) 1848/14 Aug 17 Apologising for mistake in the address of a letter (G. Cutfield, Tataraimaika) 1848/15 Sep 19 Requesting the Te Rauparaha & Rangihaeta may be prevented from attending Colonel Wakefield’s funeral (D. -

The First Taranaki War – a Divergent History

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. The First Taranaki War – A Divergent History A Thesis presented in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History at Massey University, Manawatu, New Zealand. Murray Robert Hill 2013 1 This work is dedicated to my father Robin Bernard Hill M.B.E. For laughing at my 5th Form History teacher who had said I had no future as an historian. 2 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the contribution of many people who have given their time in helping me to produce this thesis. Geoff Watson for his assistance in getting this completed. Michael Belgrave, for persistently kicking me back on track when I wandered off into things that while interesting, were not relevant. Hans-Dieter Bader, an archaeologist who has worked extensively in the Taranaki area and helped me to reassemble much of the ground of the 1860/61 period. Lt Col Colin Richardson, military historian, who was able to give me new perspectives on the nature of the Victoria Cross of 1860. Clifford Simons, military historian, for sharing his perspectives on the Maori use of intelligence and the on-going discussion about the land wars. Ian McFarlane, magazine editor and webmaster of Defending Victoria website, for sharing his experiences in attempting to improve the quality of information being presented on New Zealand official history websites. -

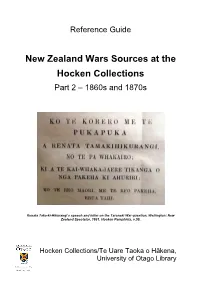

New Zealand Wars Sources at the Hocken Collections Part 2 – 1860S and 1870S

Reference Guide New Zealand Wars Sources at the Hocken Collections Part 2 – 1860s and 1870s Renata Taka-ki-Hikurangi’s speech and letter on the Taranaki War question, Wellington: New Zealand Spectator, 1861. Hocken Pamphlets, v.58. Hocken Collections/Te Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago Library Nau Mai Haere Mai ki Te Uare Taoka o Hākena: Welcome to the Hocken Collections He mihi nui tēnei ki a koutou kā uri o kā hau e whā arā, kā mātāwaka o te motu, o te ao whānui hoki. Nau mai, haere mai ki te taumata. As you arrive We seek to preserve all the taoka we hold for future generations. So that all taoka are properly protected, we ask that you: place your bags (including computer bags and sleeves) in the lockers provided leave all food and drink including water bottles in the lockers (we have a lunchroom off the foyer which everyone is welcome to use) bring any materials you need for research and some ID in with you sign the Readers’ Register each day enquire at the reference desk first if you wish to take digital photographs Beginning your research This guide gives examples of the types of material relating to the New Zealand Wars held at the Hocken. All items must be used within the library. As the collection is large and constantly growing not every item is listed here, but you can search for other material on our Online Public Access Catalogues: for books, theses, journals, magazines, newspapers, maps, and audiovisual material, use Library Search|Ketu.