By Eric Brahm

June 2004

Since the mid-1970s, an unprecedented number of states have attempted the transition to democracy. One of the significant issues Many Timorese want answers many of these states have had to deal with is how to induce different from those who caused their groups to peacefully coexist after years of conflict. Particularly since the early 1990s, the international human rights community has loss and suffering. With advocated truth commissions as an important part of the healing answers, people can start the process, and they have been suggested as part of the peace process healing process and close this of virtually every international or communal conflict that has come to horrible chapter in their lives. -- an end since. Xanana Gusmao

Advocates of truth commissions (as well as other forms of transitional And the truth will set you free. justice such as war crimes tribunals) argue that some reckoning with the past is necessary in order for former opponents to look to a peaceful shared future. This essay will discuss the evolving practice of truth commissions and explore claims made on their behalf. They are increasingly seen not as weak substitutes for trials, but as having unique benefits and as superior to trials in some respects.

What is a Truth Commission?

Truth commissions are generally understood to be "bodies set up to investigate a past history of violations of human rights in a particular country -- which can include violations by the military or other government forces or armed opposition forces."[1] Hayner delineates four main characteristics of truth commissions. [2]

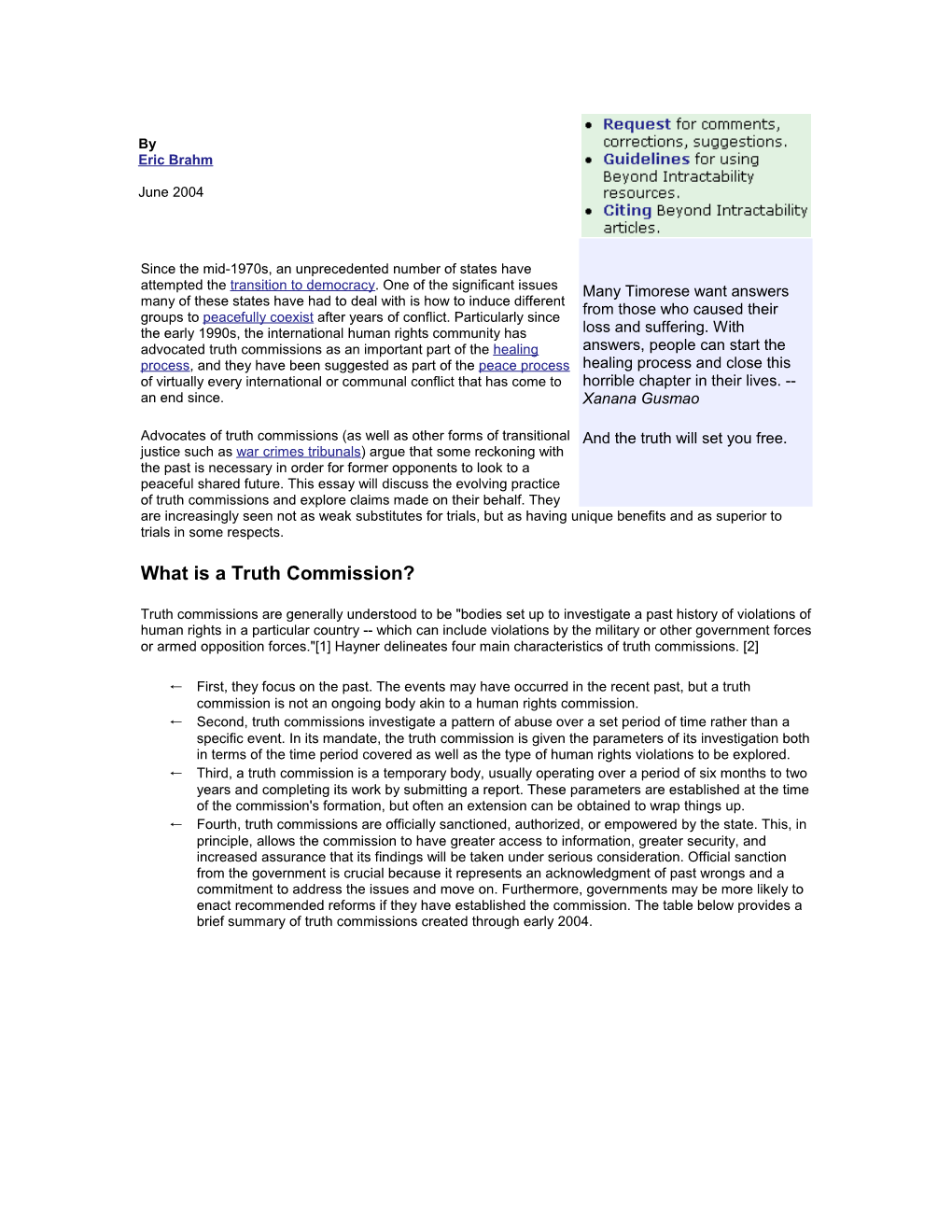

← First, they focus on the past. The events may have occurred in the recent past, but a truth commission is not an ongoing body akin to a human rights commission. ← Second, truth commissions investigate a pattern of abuse over a set period of time rather than a specific event. In its mandate, the truth commission is given the parameters of its investigation both in terms of the time period covered as well as the type of human rights violations to be explored. ← Third, a truth commission is a temporary body, usually operating over a period of six months to two years and completing its work by submitting a report. These parameters are established at the time of the commission's formation, but often an extension can be obtained to wrap things up. ← Fourth, truth commissions are officially sanctioned, authorized, or empowered by the state. This, in principle, allows the commission to have greater access to information, greater security, and increased assurance that its findings will be taken under serious consideration. Official sanction from the government is crucial because it represents an acknowledgment of past wrongs and a commitment to address the issues and move on. Furthermore, governments may be more likely to enact recommended reforms if they have established the commission. The table below provides a brief summary of truth commissions created through early 2004. Country Date of Commission Time Covered Report Publicly Issued? Uganda 1974 1971-1974 1975 Bolivia 1982-1984 1967-1982 Commission Disbanded Argentina 1983-1984 1976-1983 1985 Uruguay 1985 1973-1982 1985 Zimbabwe 1985 1983 No Uganda 1986-1995 1962-1986 No Philippines 1986 1972-1986 No Nepal 1990-1991 1961-1990 1994 Chile 1990-1991 1973-1990 1991 Chad 1991-1992 1982-1990 1992 Germanya 1992-1994 1949-1989 1994 El Salvador 1992-1993 1980-1991 1993 Rwandab 1992-1993 1990-1992 1993 Sri Lanka 1994-1997 1988-1994 1997 Haiti 1995-1996 1991-1994 Limited, 1996 Burundi 1995-1996 1993-1995 1996 South Africac 1995-2000 1960-1994 1998 Ecuador 1996-1997 1979-1996 Commission Disbanded Guatemala 1997-1999 1962-1996 1999 Nigeria 1999-2001 1966-1999 Report in Process Peru 2000-2002 1980-2000 2003 Uruguay 2000-2001 1973-1985 Report in Process Panama 2001-2002 1968-1989 2002 Yugoslavia 2002 1991-2001 Commission Ongoing East Timor 2002 1974-1999 Commission Ongoing Sierra Leone 2002 1991-1999 Commission Ongoing Ghana 2002 1966-2001 Commission Ongoing aWhile Germany conducted a truth commission consistent with the definition adopted here, it focused on the former East Germany. Comparative regional measures do not exist for the pre- and post-unification East. Because comparisons cannot be made, the case is not included in the analysis.

bRwanda is included because the commission was granted quasi-official status and received some cooperation from authorities.

cAlthough the commission issued its report in 1998, it continued to work on the granting of amnesty and making reparation recommendations.

Sources: (Hayner, 1994; Bronkhorst, 1995; Hayner, 2001; USIP, http://www.usip.org/library/truth.html).

A number of other bodies have also been created to serve the similar function of investigating the past. In some instances, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have sometimes created their own truth commissions where governments have failed to create one. For example the archbishop of Sao Paulo, with the support of the World Council of Churches, investigated human rights abuses under Brazil's military regime when the government refused their calls for a formal inquiry. Other commissions of inquiry have examined individual events.

Truth commissions also need not be national in scope. The Greensboro Truth and Community Reconciliation Project in North Carolina created a Truth and Reconciliation Commission in May 2004, to examine racially motivated killings by the Ku Klux Klan and the American Nazi Party in 1979.[3] Nor need they be governmental at all. South Africa's African National Congress created two commissions in the early 1990s to investigate the internal activities of its own organization.

When Are Truth Commission Created?

Many new democracies are confronted with a legacy of state- sponsored terror and armed insurgency. The dilemma for many new governments is that, while they are young and often weak, it must attempt to restore peace by bringing former enemies together. In order for society to move forward, it must find a way for former Mark Amstutz , a professor at combatants to live together. Purges or trials for the losing side may Wheaton College, describes the put a decisive end to the conflict in some cases. In other instances, nothing is done to address past crimes. Many conflicts, however, end factors behind South Africa's somewhere in between, where pressure for accountability is great, but remarkable transformation past conflict has either co-opted or decimated the judicial system and focusing in particular on the role perpetrators of human rights abuses retain significant power. In other of moral leadership. words, where there is a relatively even balance of forces at the transition, truth commissions are more likely.[4] International pressure also makes truth commissions, or some other form of accountability, more likely, especially as international human rights norms have grown.

As truth commissions have become more common and have gained more adherents, they have been argued to have alternative, inherent benefits of their own and should not be seen as simply a second best option to criminal prosecution. As such, in a number of recent cases, for example East Timor and Sierra Leone, truth commissions have been created alongside tribunals.

Inside the Truth Commission Process Mark Amstutz , a professor at Wheaton College, describes Recognizing each case has been unique in some respects, this section will review some of the generally common elements of truth South Africa's Truth and commission creation and operation. Reconciliation Commission and its conditional amnesty provision in particular. Establishment of a Truth Commission

There is general agreement that, if a commission is to be established, it should happen soon after the governmental transition in order to aid in this process. Witnesses and evidence will only become more difficult to find over time. Truth commissions are typically created by presidential decree. It may be more effective to have the legislature create the body because it is seen as a more democratic body, but this has been extremely rare. While it appears the parliamentary creation of a truth commission may aid in its legitimacy, there are simply not enough cases available to conclude this with certainty.

Composition of the Commission. How a truth commission will function is highly dependent on who is appointed to the commission. A number of commissions set up by new presidents were in fact highly partial. In Chad, for example, it became apparent that the truth commission was used to discredit the old regime and legitimize the new one. Where the commission is highly representative of all sides of the conflict, however, the outcome may be too inconclusive. In the case of Chile, the transition was not a clean break with the past and segments of the old regime maintained significant power. The truth commission contained an even split between Pinochet supporters and opponents, but the military still rejected the commission's findings. What has been perhaps the most common method is to appoint well-respected members of society to commissions. Being perceived as above politics makes them an ideal choice, though they need not be strictly impartial. It would be difficult to remain so after living through such an experience. In some extreme cases, governments have sought foreigners to form the commission. In the case of El Salvador, for example, the violence was seen as so polarizing that no Salvadoran could fairly assess what had happened. The UN secretary-general, with the agreement of the parties to the peace accords, selected a former Colombian president, a former Venezuelan foreign minister, and a former president of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights to conduct the truth commission.

The Mandate. When a truth commission is established, it is given a specific mandate by the authority that created it. The mandate covers such things as the commission's length of operation,[5] the time period open to investigation by the commission,[6] and what crimes are open to investigation.[7] Ideally, the commission's mandate should allow it to explore a broad range of activities in order to provide a more complete picture of the past. However, political calculation often enters in.

The Operation of Truth Commissions

Simply put, the truth commission's main goal is to establish what happened in the past. Truth commissions do not normally have the power to prosecute. They can make recommendations for prosecution, but this is quite rare. Commissions usually do not even Mark Amstutz , a professor at "name names". Often, when a truth commission has been Wheaton College, describes established, the perpetrators of the abuses have been granted how truth-seeking can be a amnesty. Because of this, there may appear to be a conflict between crucial part of social healing finding the truth and administering justice. Finally, the ability of a truth after conflict. commission to successfully conduct its mission depends on the resources it has at its disposal.

Truth vs. Justice? A central question of truth commissions is whether their search for truth is incompatible with bringing human rights violators to justice. Truth commissions do not have the power to punish, nor should they. In contrast to the courts, truth commissions do not have the same standards of proof or evidence. Where the rule of law is so eroded, courts may not be functioning or the sheer number of cases would overwhelm the system. Justice may be served in a few select cases, but the process of seeking truth will serve the greater number of people. Where the court system is functioning, it may be heavily tainted by the abusive regime and not trusted by the population to administer justice. This does not preclude, however, the use of their reports in trials and issuing warrants.

Despite the tendency to avoid assigning individual responsibility, some commissions have "named names" where a preponderance of evidence existed and have recommended that these people be brought to trial. The revelation of names has also led to cases of accused individuals being victims of vigilante violence.

In terms of facilitating healing, trials also focus on the perpetrator rather than the victim. Truth commissions, however, are not adversarial like court proceedings, thereby providing a more comfortable environment for victims.

The Question of Amnesty. With human rights violators often still playing prominent roles in society, a question facing transitional states is whether to grant amnesty to promote reconciliation. This is usually not a decision truth commissions can participate in. Repressive regimes often grant themselves immunity to prevent future prosecution. Amnesties have also been passed after truth commissions to prevent their findings from reigniting conflict. Within five days of the release of the report in El Salvador, a sweeping amnesty law was passed to prevent anyone from being tried. A number of the top military leaders were eased out of the government, but they were given full pensions.[8] The South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was granted the most power in being authorized to grant amnesty in exchange for testimony. It had a committee to corroborate testimony, judge the political motivation of the crime, and make decisions as to whether the complete truth had been revealed.

Public Hearings. One variable in commissions' operation has been whether its proceedings are public. Early truth commissions had little public testimony due to the fear of retribution. The South African commission was the first big departure from this trend and, in general, it has been more common in Africa. Making the commission public does risk security and unchecked accusations. However, public proceedings also lend the commission greater public legitimacy. The public can see how the commission is operating and there is less opportunity to suppress the commission's findings.

Evidence. Truth commissions seek to collect evidence from a variety of sources. Information from official sources may exist. However, it may be destroyed or the commission may lack the power to subpoena it. Government cooperation is highly variable. The military, in particular, is often less than forthcoming with information. Files are destroyed. Events may have taken place far in the past, which makes finding information extremely difficult. Yet, often records remain. Pressure and popular will is often decisive in determining whether commissions gain access to this information. The commission staff must also have expertise in collecting forensic evidence. Perhaps, the most crucial and most powerful form of evidence is through interviews. Victims telling their stories play a central part of the commission's mission. Particularly where reparations are involved, the poor may have particular incentive to come forward. However, linking fears of reprisals often inhibit the willingness of victims to cooperate.

Resources. In order to complete its task, a truth commission must be granted sufficient resources. This is not an easy proposition for transitional states, many of which are poor to begin with and face tremendous rebuilding costs after restoring relative peace. Most truth commissions find themselves short of the resources necessary to conduct a full investigation. The commission needs to hire a staff to conduct interviews and collect data. A crucial variable for the success of a commission is the size of its staff. The South African TRC, for example, was given a staff of three hundred and a budget of $18 million per year for its two-and-a-half year existence.[9] By contrast, due to lack of office space, Chad's truth commission was forced to set up its headquarters within the former secret detention center of the security forces.[10] Investigators also need to reach remote areas to interview witnesses and visit sites of key events. This is often not easy due to poor infrastructure. Sources of financial support may be available from the international human rights community, but this may raise questions for some about the legitimacy of the commission.

Findings: The Truth Commission Report

The commission's final report is its legacy. It is a summary of the key findings. Patterns of abuse are outlined. Most importantly, the commission's report provides recommendations for rebuilding society. One of the key aspects of the report is the highlighting of the institutional factors that facilitated the abuse of human rights. Recommendations often center on judicial, military, and police reform. Some observers argue the implementation record of reform recommendations is often poor.[11] Reforms are often debated for years, may require legislation or a constitutional amendment, and may become overshadowed by other issues as time goes on.

In order to have maximum impact on society, the report should be widely disseminated. It seems unlikely a truth commission can be considered a success if its findings are not made public. It is important that the entire population has access to the findings to better understand the trauma they have experienced. If a report is kept out of public view, it will raise suspicions about the government's role in the violence.

Truth commissions also make recommendations for reparations to be given to victims of state terror. It is impossible to put a price tag on the suffering that victims have endured, but reparations are another sign of the government's commitment to healing old wounds. Reparations may take the form of cash payments or pensions. It may also include free access to health care and psychiatric treatment. Due to resource constraints, however, these more direct payments are rarely adequate. Symbolic reparations, through public memorials or national remembrance days, are often part of commission recommendations.

International Role

The international community can be of great help in supporting transitional justice. In general, the international community can give advice to the new government. Veterans of past truth commissions have increasingly become persuasive advocates and teachers for other countries seeking to learn from past experiences.[12] Because domestic civil society is often weak, international support of this kind is also helpful. States and NGOs often financially support the operation of commissions. Recently, international institutions have become more involved in the actual running of truth commissions. The Guatemalan and Salvadoran peace accords called for truth commissions under the auspices of the United Nations. The government of Burundi asked the United Nations to set up a commission of inquiry in 1995 because it did not feel it was strong enough to do so itself.[13] The international community can be helpful by acting as a neutral arbiter pressuring all sides to compromise.

The international dimension is not entirely positive, however. Of the case thus far, there has generally been little truth commission investigation of the international role in civil conflict. Relying on international assistance to conduct the commission can also have negative effects. They may lack knowledge of the domestic environment. If they are heavily involved in the administration of the commission, they will invariably go home perhaps minimizing the intended impact on society. It is also easier to dismiss the process as a foreign imposition.

Strengths and Weaknesses

Margaret Popkin and Naomi Roht-Arriaza describe four main goals for truth commissions.

1. Truth commissions seek to contribute to transitional peace by "creating an authoritative record of what happened; 2. providing a platform for the victims to tell their stories and obtain some form of redress; 3. recommending legislative, structural or other changes to avoid a repetition of past abuses; and 4. establishing who was responsible and providing a measure of accountability for the perpetrators."[14]

On a basic level, truth commissions uncover the details of past crimes. In many cases, they serve to officially acknowledge what many already know about the past. In this difficult time, it is a way for a new government to establish legitimacy by espousing democratic ideals, the rule of law, formal legal equality, and social justice. As such, although they investigate the past, truth commissions are as much about looking forward as back. They are part of an attempted social transformation to bring about a more peaceful society. Desmond Tutu explains the reason for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) this way: "While the Allies could pack up and go home after Nuremberg [war crimes tribunals following WWII], we in South Africa had to live with one another."[15] Societal reconciliation is an often-professed goal of truth commissions, but almost always beyond its reach at least for a truth commission on its own.

Furthermore, it is argued that they can provide a deterrent for the future and end collective denial. Although lacking in power, truth commissions represent a signal by the new government to domestic and international audiences that they intend to make a break with the history of impunity. While not all have held public proceedings, they have often received strong media attention, which gives them a greater opportunity to influence the national psyche. Participation on the part of significant political actors may signal a commitment to peace as do proceedings that discredit those associated with past crimes on all sides of the conflict. Truth commission advocates argue that calling perpetrators to account, even in a weaker venue like a truth commission, reveals the vulnerability of those once in power and knowing these acts have been firmly denounced is empowering to the general public. Although naming names of those responsible has been rare, it is not difficult to identify those in charge of institutions criticized by the commission. Findings may discredit those responsible.[16] In short, the logic of truth commissions is that exposing the factors that allowed these crimes to occur goes a long way toward preventing their recurrence. At the same time, certainly not all are satisfied with foregoing retributive justice.[17]

More significant, however, is delivering what has become known as restorative justice. The process of coming to terms with the past can have great psychological benefit for those seeking trauma healing. By providing official acknowledgment of past crimes, the process helps restore dignity to victims. Sometimes describing the terrible details can bring peace. A truth commission offers victims a chance to finally tell what happened to them: "The chance to tell one's story and be heard without interruption or skepticism is crucial to so many people, and nowhere more vital than for survivors of trauma." [18] Advocates of truth commissions often point to research on crime victims. In many cases, being able to tell their story is tremendously therapeutic for victims of violence. Truth commissions can assist in the healing process by the fact that the listener has official status.

The therapeutic benefits, however, warrant further examination. While telling one's story and hearing details of loved ones' fates are sometimes beneficial, for other victims, these experiences have quite different effects, bringing back old anger and triggering post-traumatic stress. The benefit a crime victim receives from retelling their story is often part of a long-term treatment process. With a truth commission, however, a victim usually has only a few minutes and few resources for follow-on care. In terms of the impact on the general populace, the evidence is also mixed. At the individual level, data is relatively scarce with the notable exception of South Africa. Where the data do exist, the ability of a truth commission's findings to soothe negative feelings is mixed. A survey conducted in South Africa revealed that two-thirds of the respondents felt the truth commission process had harmed race relations and made people angrier.[19] In El Salvador, by contrast, a poll after the commission's conclusion indicated widespread acceptance of the commission's findings.[20]

Despite positive potential, truth commissions have sometimes served merely as a means of legitimizing new governments. While they are generally associated with regime transitions, that transition need not be toward democracy. The 1986 Ugandan commission and the case of Chad are emblematic of truth commissions being used mainly as a tool to discredit the previous regime. In other cases, such as Uganda's 1974 commission, it seemed not to be a sincere attempt to rectify the past, but rather a flimsy effort to placate international pressure. Furthermore, in places such as Zimbabwe and Haiti, the publication of the commission's report was hindered or completely stopped because it was too critical of the new government. In Bolivia and Ecuador, commissions were disbanded before completing their work because the investigations became too politically sensitive. Clearly, the commissions cannot be solely blamed for this -- the political will to act on their findings did not exist.

In sum, the general population, as well as human rights advocates, often expect too much from truth commissions. First, they may have an impossible mission. The needs of victims may be incompatible with the needs of society. Second, it is argued they do not go far enough to deal with the past or generate reconciliation. They do not have the power to punish and have no authority to implement reforms. Third, wiping the slate clean benefits those who have committed human rights violations. This damages victims' self-esteem and denies them justice. Finally, erasing history is difficult. At minimum, truth commissions pursue different types of truth. They investigate the details of specific events while at the same time attempting to explain the factors and circumstances behind the gross human rights violations the state experienced. In short, truth commissions often seem asked to do too much with too little.

It bears repeating that truth commissions are but one component of an effort to bring about peace. It would be unfair to judge their success solely on the future stability of the new regime or on some measure of future levels of violence or adherence to the rule of law. There are too many other variables involved in determining whether domestic tranquility will be maintained. At the same time, researchers need to do a better job of determining what impact truth commissions have and under what circumstances they might be most effective. Claims of their utility are often based on anecdotal evidence. Survey research is one avenue that should be further explored,[21] although for past cases one can only now draw on vague recollections. No pre- and post-tests are possible. Another avenue to explore is greater comparative work. Truth commission experiences have certainly been compared, but if one is interested in trying to identify what impact the commission itself has had, it would seem important to include transitional societies that did not conduct truth commissions as well.

The Future of Truth Commissions

Truth commissions are very much in favor within the international human rights community for ending civil conflict. They are clearly not necessary, however, for one can point to a number of cases of relatively peaceful transitions to democracy in which the past has not been systematically examined. In places like Mozambique and Cambodia where there appears to be a consensus that the past should be left alone, that sentiment should be respected.[22] There is a sense there that rehashing the past will bring a return of violence. There is also a lack of political interest in investigating the past and there are other urgent priorities such as rebuilding. The rebuilding process itself may help reconciliation by focusing energies toward a common goal. Despite the growing prevalence of the truth commission phenomenon, we do not yet have a clear understanding of their effectiveness. Studies have typically described operations, but it is not clear whether truth commissions have effects or that there are other factors causing an impact. Evidence is often anecdotal. Many of the existing comparative studies focus on a few prominent cases, namely Argentina, Chile, El Salvador, South Africa, and Guatemala. Most of the lessons learned from truth commission experiences have thus been drawn from only a small number of cases. Still, they are intuitively appealing and have many supporters in global civil society. The growing body of international human rights law is increasingly recognized as containing an obligation to deal with past crimes. As a result, the pressure to examine a legacy of human rights abuses is likely to remain strong.

[1] Priscilla B. Hayner, "Fifteen Truth Commissions -- 1974 to 1994: A Comparative Study." In Human Rights Quarterly, Volume: 16 Issue: 4. 1994, p. 558.

[2] Priscilla B. Hayner, Unspeakable Truths. New York: Routlege, 2001, p. 14.

[3] http://www.gtcrp.org/

[4] Barahona de Brito, A., P. Aguilar, et al. (2001). Introduction. The politics of memory: transitional justice in democratizing societies. A. Barahona de Brito, C. Gonzalez Enriquez and P. Aguilar. Oxford, Oxford University Press: 1-39.; Hayner, Priscilla B. (1999). In Pursuit of Justice and Reconciliation: Contributions of Truth Telling. Comparative Peace Processes in Latin America. C. J. Arnson. Washington DC, Woodrow Wilson Center Press: 363-383.Pion-Berlin, David. (1994). "To Prosecute or to Pardon? Human Rights Decisions in the Latin American Southern Cone." Human Rights Quarterly 16(1): 105-130.;

[5] This has typically been six months to two years.

[6] This will of course vary based on the nature of the conflict the commission is examining, but may also be shaped by political considerations to make one side appear more or less responsible.

[7] Truth commissions' mandates often restrict investigations to particular type of human rights violations or to violations that took place in particular locations. In Chile, for example, the commission was only permitted to investigate "disappearances after arrest, executions, and torture leading to death committed by government agents or people in their service, as well as kidnappings and attempts on the life of persons carried out by private citizens for political reasons." (from the Chilean Commission's Final Report). Thus, their mandate did not include investigating cases of torture unless the victim died. Those who survived were not categorized as victims by the truth commission.

[8] Priscilla B. Hayner, Unspeakable Truths. New York: Routlege, 2001, p. 40.

[9] Ibid., p. 41.

[10] Ibid., p. 58.

[11] Ibid.

[12] For example, The International Center for Transitional Justice,http://www.ictj.org/, was established by former South African TRC member Alex Boraine with help from the Ford Foundation.

[13] Hayner 2001, p. 67.

[14] Quoted in Christie, Kenneth (2000). The South African Truth Commission. New York, St. Martin's Press, p. 61. [15] Desmond Mpilo Tutu, No Future Without Forgiveness. Doubleday, 2000., p. 21.

[16] Such shaming has sometimes led to vigilante justice, however.

[17] See, for example, Reed Brody (2001). "Justice: The First Casualty of Truth?" The Nation, April 30.

[18] Minow, Martha (1998). Between vengeance and forgiveness : facing history after genocide and mass violence. Boston, Beacon Press.

[19] Hayner 2001.; Tepperman, Jonathan D. (2002). "Truth and Consequences." Foreign Affairs 81(2): 128- 145.

[20] Popkin, Margaret L. and Naomi Roht-Arriaza (1995). "Truth as Justice: Investigatory Commissions in Latin America." Law & social inquiry 20(1).

[21] On public sentiment in South Africa, see Gibson, James L. (2004). Overcoming apartheid: can truth reconcile a divided nation? New York, Russell Sage Foundation.; Gibson, James L. and Amanda Gouws (2003). Overcoming intolerance in South Africa: experiments in democratic persuasion. New York, Cambridge University Press.

[22] Hayner 2001.

Use the following to cite this article: Brahm, Eric. "Truth Commissions." Beyond Intractability. Eds. Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess. Conflict Research Consortium, University of Colorado, Boulder. Posted: June 2004

Sources of Additional, In-depth Information on this Topic

Additional Explanations of the Underlying Concepts:

Online (Web) Sources

Brahm, Eric. "Burying the Past: Making Peace and Doing Justice After Civil Conflict -- Summary." Conflict Research Consortium, 2000. Available at: http://www.beyondintractability.org/booksummary/10047/.

This is a summary of Nigel Biggar's "Burying the Past: Making Peace and Doing Justice After Civil Conflict."

Brahm, Eric. "Closing the Books: Transitional Justice in Historical Perspective -- Summary." Conflict Research Consortium, 2000. Available at: http://www.beyondintractability.org/booksummary/10185/.

This is a summary of Jon Elster's "Closing the Books: Transitional Justice in Historical Perspective."

Brahm, Eric. "Confronting Past Human Rights Violations: Justice vs. Peace in Times of Transition -- Summary." Conflict Research Consortium. Available at: http://www.beyondintractability.org/booksummary/10029/.

This is a summary of Chandra Lekha Sriram's "Confronting Past Human Rights Violations: Justice vs. Peace in Times of Transition"

Simpson, Graeme. A Brief Evaluation of South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation commission: Some Lessons for Societies in Transition. Available at: http://www.csvr.org.za/papers/paptrce2.htm. Provides a critical assessment of what the TRC was and was not able to achieve with an eye toward learning for the future.

Democracy and Deep Rooted Conflict: 4.10 - Reckoning for Past Wrongs: Truth Commissions and War Crimes Tribunals. IDEA. Available at: Click here for more info. "When communities have been victimized by the government or by another group during a conflict, underlying feelings of resentment and the desire for revenge cannot be alleviated unless the group is allowed to mourn the tragedy and senses that wrongs have been acknowledged, if not entirely vindicated. In an environment where there is no acknowledgement of or accountability for past violent events, tensions among former disputants persist. Hence, confronting and reckoning with the past is vital to the transition from conflict to democracy. This section addresses two mechanisms to achieve this accounting: truth commissions and war-crime tribunals. "

Facing History and Ourselves. Available at: http://www.facinghistory.org. This organization is based around helping people to understand the present and future by educating them about the past. It seeks to develop programs that would allow students to think critically about the past by emphasizing morality in history. The website has links to new articles discussing current world events and also provides resources for understanding these events. There are also resources like academic articles, films, books, and teaching tools provided at this site.

Strategic Choices in the Design of Truth Commissions. Available at: http://www.truthcommission.org/. A society emerging from a regime marked by grave and serious violations of human rights faces the complex challenge of how best to deal with the past. The establishment of a Truth Commission has helped several countries through this process. In the course of establishing such Commissions, leaders and decision makers are faced with a variety of political and structural choices. This website, a collaboration of the Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School, Search for Common Ground, and the European Centre for Common Ground, is part of a process designed to help build a Truth Commission that fits their unique needs. We have organized the leading research on past Truth Commissions in a manner that is oriented towards decision making, to enable designers of future Commissions to identify the critical factors and potential solutions relevant to their societies.

Ball, Patrick and Audrey R Chapman. "The Truth of Truth Commissions: Comparative Lessons from Haiti, South Africa, and Guatemala." Human Rights Quarterly , 2001 Available at: Click here for more info.

"This article identifies some of the complexities and factors shaping the efforts of truth commissions. It also evaluates the kinds of truths that truth commissions can most appropriately seek to determine."

Truth Commissions and Conflict Prevention. World Peace Foundation. Available at: http://www.worldpeacefoundation.org/truthcommissions.html. "The project continues to examine the many ways in which the concept of a truth commission, and the actual establishment of truth commissions in conflict-prone regions, can contribute to the peaceful prevention of intrastate hostilities."

Truth Commissions Digital Collection. United States Institute for Peace. Available at: http://www.usip.org/library/truth.html. A page describing what truth commissions are and how they are applied to conflicts. Also listed are quite a few examples of recent and ongoing truth commissions functioning all around the world. This website provides the United States Institute of Peace's comprehensive definition of truth commissions as well as a summary of all truth commissions to date.

Truth Commissions: A Comparative Assessment. Harvard Law School. Available at: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0972103309/. An interdisciplinary discussion held at Harvard Law School in May, 1996 on the subject of Truth Commissions.

Gairdner, David. Truth in transition: the role of truth commissions in political transition in Chile and El Salvador. Available at: http://www.cmi.no/publications/1999/rep/r1999-8.pdf. Truth Commissions are increasingly being used as one mechanism in a broader strategy to consolidate democratic governance following a period of authoritarian rule. However, there has been little research on the impact of Commissions, including identifying the aspects of a transition process that they are able to address. Accordingly, this study offers a framework for understanding the role of Truth Commissions in political transition. It argues that Commissions have the potential to support the consolidation of a democratic polity when they contribute towards two essential tasks. First, Commissions must act to dismantle enclaves of authoritarian power that were transplanted from the past into the post-transition polity. The presence of these enclaves undermines the democratic qualities of the new polity and renders the transition process incomplete. Second, Commissions must simultaneously help to create new structures and values on which democratic governance can be built. The interaction between the Commissions and authoritarian enclaves takes place in specific sites of transition in a given society; Strategic Behaviour (the institutional matrix of constraints and opportunities that shape interaction between social actors), Social Epistemes (bodies of knowledge and ways of imagining relations within a political collective) and the Material Environment (economic structures). Enclaves not falling within the mandate of a Commission must be the subject of action from other initiatives.

Offline (Print) Sources

Biggar, Nigel, ed. Burying the Past: Making Peace and Doing Justice after Civil Conflict. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, March 2001. This is a collection of essays drawn together by Nigel Biggar (Professor of Theology at the University of Leeds) that explores the challenges of establishing democracy after a period of violent and prolonged civil conflict. Relationships within the populace must be restored so that reprisals and revenge do not undermine or subvert emerging democratic processes. Click here for more info.

Elster, Jon. Closing the Books: Transitional Justice in Historical Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, September 6, 2004. This books examines historical examples of the process of transitional justice. It discusses how different countries have dealt with the fall of regimes, war criminals, and moving past the memories of conflict. Click here for more info.

Sriram, Chandra Lekha. Confronting Past Human Rights Violations: Justice vs. Peace in Times of Transition. New York: Frank Cass, 2004. This book challenges transitional justice literature, which aruges that in a period of transition governments much choose between ensuring peace and attaining justice. This Sriram believes that there is a peace and justice continuum and rather than putting the two in competition with each other. Click here for more info.

Minow, Martha L. "Truth Commissions." In Between Vengeance and Forgiveness: Facing History After Genocide and Mass Violence. Boston: Beacon Press, 1998. Pages: 52-90. Chapter on the option of truth commissions to deal with atrocity.

Garro, Alejandro M. and et al. "Argentina." In Transitional Justice: How Emerging Democracies Reckon with Former Regimes Vol.II: Country Studies. Edited by Kritz, Neil J., ed. Washington DC: United States Institute of Peace, 1995. This chapter focuses on transitional justice issues surrounding Argentina's democratic transition.

Minow, Martha L. Between Vengeance and Forgiveness: Facing History After Genocide and Mass Violence. Boston: Beacon Press, 1998. This book looks at the capacity and limitations of formal national responses to genocide, systematic rapes, and mass torture. Such responses have come in the form of legal proceedings, truth commission, reparations, and memorials, and give rise to questions about retributive justice, forgiveness, and healing.

Correa S., Jorge and et al. "Chile." In Transitional Justice: How Emerging Democracies Reckon with Former Regimes Vol.II: Country Studies. Edited by Kritz, Neil J., ed. Washington DC: United States Institute of Peace, 1995. The articles collected in this chapter discuss the shape of transitional justice in the Chilean transition to democracy.

Hayner, Priscilla B. "Commissioning the Truth: Further Research Questions." Third World Quarterly 17:1, 1996. This article provides a brief overview of truth commissions and the attributes important to make them most effective. Furthermore, she outlines a number of important questions to be examined regarding the role of truth commissions.

Hayner, Priscilla B. "Fifteen Truth Commissions- 1974 to 1994: A Comparative Study." Human Rights Quarterly 16:4, 1994. This article is one of the most comprehensive studies of truth commissions written up to the published date, 1994. The author clearly defines truth commissions and their purposes, and then reviews the 15 truth commissions that existed up to that point. She also discusses the change from commissions being set up by government branches to commissions being set up by international organizations like the UN. The article also outlines such key components of commissions as timing, authority, representation, scope, limitations, budget, and outcome.

Gibson, James L. Overcoming Apartheid: Can Truth Reconcile a Divided Nation. New York: Sage Foundation, 2004. In this book, Gibson examines whether or not truth commissions have had significant results in reconciling the divided parts of South Africa. He finds that truth and reconciliation committees have aided in democratization of South Africa, even though most Africans believe that they only open old wounds.

Gibson, James L. Overcoming apartheid: can truth reconcile a divided nation?. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2004. Overcoming Apartheid reports on the largest and most comprehensive study of post-apartheid attitudes in South Africa to date, involving a representative sample of all major racial, ethnic, and linguistic groups. Grounding his analysis of "truth" in theories of collective memory, Gibson discovers that the process has been most successful in creating a common understanding of the nature of apartheid. His analysis then demonstrates how this common understanding is helping to foster "reconciliation," as defined by the acceptance of basic principles of human rights and political tolerance, rejection of racial prejudice, and acceptance of the institutions of a new political order. Gibson identifies key elements in the process - such as acknowledging shared responsibility for atrocities of the past - that are essential if reconciliation is to move forward. He concludes that without the truth and reconciliation process, the prospects for a reconciled, democratic South Africa would diminish considerably. Gibson also speculates about whether the South African experience provides any lessons for other countries around the globe trying to overcome their repressive pasts.

Levy, Janet and Alex Boraine, eds. The Healing of a Nation?. Cape Town: Justice in Transition, 1995.

This book is a collection of papers delivered at a conference in July 1994 on the subject of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. As such it serves as a window on debates now gripping the country as South Africans navigate their way through these difficult questions.

Kaye, M. "The role of truth commissions in the search for justice, reconciliation and democratisation: The Salvadorean and Honduran cases." Journal of Latin American Studies 29, 1997. The truth commissions in El Salvador and Honduras attempted to offer the transitional civilian governments a way to balance their moral and legal obligations with practical political constraints; namely to reconcile calls from different sectors of society to either punish or forgive those responsible for past human rights violations; and to establish new and independent institutions without precipitating a backlash from vested interests which could derail the whole democratic transition. This paper examines the parameters in which these truth commissions operated, and evaluates the role they played in trying to facilitate the democratisation processes in Honduras and El Salvador.

Chapman, Audrey R and Patrick Ball. "The truth of truth commissions: Comparative lessons from Haiti, South Africa, and Guatemala." Human Rights Quarterly 23:1, 2001. This article provides first an overview of truth commissions and examines how different conditions have had different effects in various countries, particularly Haiti, South Africa, and Guatemala.

Hayner, Priscilla B. and Mark Freeman. "Truth-Telling." In Reconciliation after violent conflict : a handbook. Edited by Bloomfield, David, ed. Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, 2003. The chapter begins with a review of different conceptions of reconciliation. It then proceeds to discuss truth commissions and their contribution to reconciliation. It discusses pros and cons of truth commissions and various attributes. Chapman, Audrey R. "Truth Commissions as Instruments of Forgiveness and Reconciliation." In Forgiveness and Reconciliation: Religion, Public Policy, and Conflict Transformation. Edited by Petersen, Rodney L. and Raymond G. Helmick, eds. Philadelphia: Templeton Foundation Press, 2001. This article succinctly summarizes the key components of, benefits of, and problems with truth commissions. The author then focuses on the theological ramifications of truth commissions, including the idea of truth leading to forgiveness

Ensalaco, Mark. "Truth Commissions for Chile and El-Salvador - a Report and Assessment." Human Rights Quarterly 16:4, 1994. This article provides a comparison of two truth commissions assessing their impacts on the post-conflict environment.

Truth Commissions: A Comparative Assessment (WPF Report #16). World Peace Foundation, January 1, 1997. When civil wars or intrastate conflicts end, and dictatorships, military juntas, or other repressive authoritarian regimes are defeated by humanitarian-minded victors, creating a truth commission is one way for society and individuals to deal with the atrocities of the recent past. Because truth commissions vary in their philosophies, missions, compositions, procedures, results, and successes, the World Peace Foundation and the Human Rights Program of the Harvard Law School gathered a panel to study and discuss these and other issues concerning the relevance and efficacy of truth commissions. This report is an edited transcript of their meeting.

Gibson, James L. "Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation: Judging the Fairness of Amnesty in South Africa." American Journal of Political Science 46:3, 2002. Nations in transition to democratic governance often must address the political atrocities committed under the ancien regime. A common response is some sort of 'truth commission', typically with the power to grant amnesty to those confessing their illicit deeds. Based on a survey of the South African mass public, my purpose here is to investigate judgments of fairness of amnesty. My analysis indicates that justice considerations do indeed influence fairness fairness assessments. Distributive justice matters- providing victims compensation increases perceptions that amnesty is fair. But so too do procedural (voice) and restorative (apologies) justice matter for amnesty judgements. I conclude that the failure of the new regime in in South Africa to satisfy expectations of justice may have serious consequences for the likelihood of succesfully consilidating the democratic transition.

Oder, Arthur H. and et al. "Uganda." In Transitional Justice: How Emerging Democracies Reckon with Former Regimes Vol.II: Country Studies. Edited by Kritz, Neil J., ed. Washington DC: United States Institute of Peace, 1995. This chapter provides a summary of efforts to achieve justice for past human rights abuses in Uganda since the transition in the early 1980s.

Hayner, Priscilla B. Unspeakable Truths: Confronting State Terror & Atrocity. New York: Routledge, September 1, 2001. Hayner provides a very accessible account of why a country would opt to create a truth commission. She provides a balanced discussion on the healing power of truth. Our understanding on this point is hazy, as anecdotal evidence exists both for and against. However, she does agree with the view that an unaddressed past can fester. Click here for more info.

Americas Watch and et al. "Uruguay." In Transitional Justice: How Emerging Democracies Reckon with Former Regimes Vol.II: Country Studies. Edited by Kritz, Neil J., ed. Washington DC: United States Institute of Peace, 1995. This chapter contains a collection of pieces related to transitional justice in 1980s Uruguay.

Return to Top

Examples Illustrating this Topic: Online (Web) Sources

Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor. Available at: http://www.easttimor-reconciliation.org/. This site provides information about the background and mandate of the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor. It also has links to Commission news, articles and documents.

Odendaal, Andries. "For All Its Flaws: The TRC as a Peacebuilding Tool." , April 1998 Available at: http://ccrweb.ccr.uct.ac.za/archive/two/6_34/p04_flaws.html.

The author reflects on the paradoxes and lessons of South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) as an experiment in conflict resolution and peacebuilding.

INCORE Guide to Internet Sources on Truth and Reconciliation. INCORE. Available at: http://www.incore.ulst.ac.uk/services/cds/themes/truth.html. This page includes links to information about truth and reconciliation. At present, most of the sources available on the internet relate almost exclusively to South Africa, Rwanda, and Bosnia-Herzgovinia. There are a smaller number of sources relating to the issue in Latin America. These will be expanded as and when the material becomes available on the internet

Offline (Print) Sources

Levy, Janet, Ronel Scheffer and Alex Boraine, eds. Dealing with the past: truth and reconciliation in South Africa. Cape Town: IDASA, 1997. This edited volume is the result of a conference of participants and activists from around the world sharing experiences of dealing with the past from various country experience.

Humphrey, Michael. From Terror to Trauma: Commissioning Truth for the National Reconciliation. This article discusses the use of South Africa's TRC as a way of shifting the national pain brought on by apartheid from one of terror to trauma. Humphrey argues that South Africa believed that the nation, like individuals, can more easily deal with trauma than terror. Through truth telling (testimony), the adjustment from terror to trauma can take place. However, he argues that the formula "revealing is healing" is essentially incorrect because all individuals handle trauma in very different ways. He summarizes as follows: "the danger is that as set piece ritual strategies for national reconciliation, truth commissions produce abstracted and homogenized outcomes that become increasingly dissonant with the lives people are living. While the TRC will no doubt come to be seen as an historic event in the transition in South African national identity it cannot actually heal the suffering of individuals. Reconciliation is a partnership which re- establishes the basis for community life, not something conceded by the victims (24)."

Rigby, Andrew. Justice and Reconciliation: After the Violence. Boulder: L. Rienner, 2001. Examines mechanisms aimed to promote reconciliation after widespread crimes. Has chapters covering post-WWII purges in Europe, Spain, Latin American truth commissions, post-communist Eastern Europe, South Africa, Palestine, and third-party intervention.

Tutu, Desmond Mpilo. No Future Without Forgiveness. Doubleday, 2000. This is a first-hand account of South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Desmond Tutu's book outlines the reasons why South Africa preferred a truth and reconciliation commission to a war crimes tribunal. Desmond Tutu argues that truth commissions were the only viable option for South Africa following apartheid. He believes that the future depends on dealing with the past in a way that paves the way for a future of coexistence and understanding.

Shea, Dorothy. The South African Truth Commission: The Politics of Reconciliation. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2000. Reviews circumstances surrounding the creation and operation of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission. discusses lessons for countries that may want to utilize truth commissions in the future.

Bronkhorst, Daan. Truth and Reconciliation, Obstacles and Opportunities for Human Rights. Amsterdam: Amnesty International Dutch Section, 1995. This volume provides an overview of a variety of types of commissions of investigation that have been utilized historically.

Truth v. Justice: The Morality of Truth Commissions. Princeton University Press, September 1, 2000. Here, leading philosophers, lawyers, social scientists, and activists representing several perspectives look at the process of truth commissioning in general and in post-apartheid South Africa. They ask whether the truth commission, as a method of seeking justice after conflict, is fair, moral, and effective in bringing about reconciliation. The authors weigh the virtues and failings of truth commissions, especially the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, in their attempt to provide restorative rather than retributive justice. They examine, among other issues, the use of reparations as social policy and the granting of amnesty in exchange for testimony. Most of the contributors praise South Africa's decision to trade due process for the kinds of truth that permit closure. But they are skeptical that such revelations produce reconciliation, particularly in societies that remain divided after a compromise peace with no single victor, as in El Salvador. Ultimately, though, they find the truth commission to be a worthy if imperfect instrument for societies seeking to say "never again" with confidence. - Amazon.com

Return to Top

Audiovisual Materials on this Topic:

Offline (Print) Sources

Gacaca - Living Together Again in Rwanda? . Directed and/or Produced by: Aghion, Anne. First Run Icarus Films. 2002. This film tracks the actions of the Gacaca tribunals in Rwanda that allow citizens to participate in the justice process. Click here for more info.

Long Night's Journey into Day: South Africa's Search for Truth and Reconciliation . Directed and/or Produced by: Hoffmann, Deborah and Frances Reid. California Newsreel. 2000. This film follows several South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission cases over a two-year period. Click here for more info.