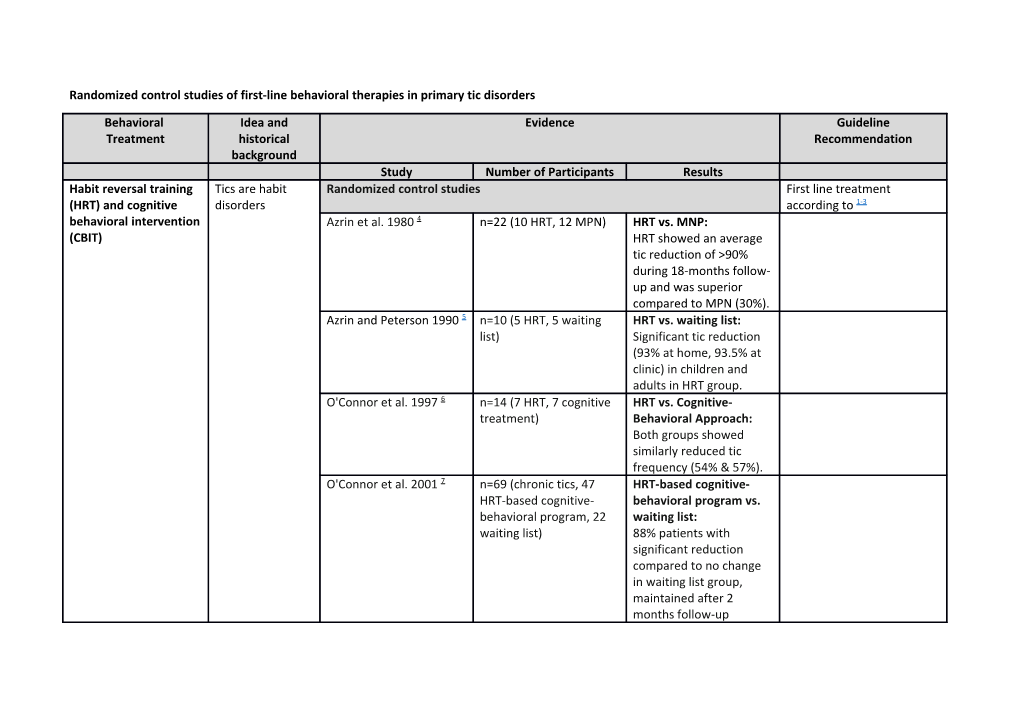

Randomized control studies of first-line behavioral therapies in primary tic disorders

Behavioral Idea and Evidence Guideline Treatment historical Recommendation background Study Number of Participants Results Habit reversal training Tics are habit Randomized control studies First line treatment (HRT) and cognitive disorders according to 1-3 behavioral intervention Azrin et al. 1980 4 n=22 (10 HRT, 12 MPN) HRT vs. MNP: (CBIT) HRT showed an average tic reduction of >90% during 18-months follow- up and was superior compared to MPN (30%). Azrin and Peterson 1990 5 n=10 (5 HRT, 5 waiting HRT vs. waiting list: list) Significant tic reduction (93% at home, 93.5% at clinic) in children and adults in HRT group. O'Connor et al. 1997 6 n=14 (7 HRT, 7 cognitive HRT vs. Cognitive- treatment) Behavioral Approach: Both groups showed similarly reduced tic frequency (54% & 57%). O'Connor et al. 2001 7 n=69 (chronic tics, 47 HRT-based cognitive- HRT-based cognitive- behavioral program vs. behavioral program, 22 waiting list: waiting list) 88% patients with significant reduction compared to no change in waiting list group, maintained after 2 months follow-up Wilhelm et al. 2003 8 n=29 (16 HRT, 13 HRT vs. Supportive supportive Psychotherapy: psychotherapy) Significant improvement in the habit reversal group, maintained at 10- month follow-up. Verdellen et al., 2004 9 n=43 (22 HRT, 21 HRT vs. ERP: Significant exposure and response improvement for both prevention) groups Deckersbach et al., 2006 n= 30 (15 HRT, 15 HRT vs. Supportive 10 supportive Psychotherapy: HRT only psychotherapy) reduced tic severity. Both groups improved life- satisfaction and psychosocial functioning. Effects maintained at 6 months follow-up. Piacentini et al., 2010 11 n= 126 (61 HRT/CBIT, 65 HRT/CBIT vs. Supportive supportive Psychotherapy: psychotherapy) Significant improvement in HRT/CBIT (52.5%) compared to supportive psychotherapy (18.5%). Maintained in 87% at 6- months follow-up. Wilhelm et al. 2012 12 n= 122 (63 HRT/CBIT, 59 HRT/CBIT vs. Supportive supportive Psychotherapy: psychotherapy) Significant improvement in HRT (38.1%) compared to supportive psychotherapy (6.4%). Maintained at 6-months follow-up. Himle et al. 2012 13 n= 18 analyzed (10 Telehealth HRT/CBIT vs. telehealth, 8 face-to-face face-to-face HRT/CBIT: HRT/CBIT) Both treatments resulted in significant tic reduction with no between group differences. Acceptability and therapist-client alliance ratings were strong for both groups. Seragni et al. 2015 14 n= 21 (11 HRT, 10 HRT vs. Treatment as treatment as usual) usual: Tic reduction and improved global functioning in both groups, without significant changes in terms of Quality of Life (high drop-out quote) McGuire et al., 2015 15 n=240 (baseline; 122 HRT/CBIT vs. supportive HRT/CBIT) psychotherapy: HRT/CBIT outperformed supportive psychotherapy across tic type and presence of urges. Baseline urge presence was associated with tic remission for CBIT but not psychotherapy. Specific bothersome tics were more likely to remit with CBIT relative to supportive psychotherapy. Yates et al. 2016 16 n= 33 (17 HRT, 16 HRT vs. Education (both education) applied as group treatment): HRT led to greater reductions in tic severity than education. Ricketts et al. 2016 17 n = 20 (12 HRT/CBIT, 8 Internet protocol- waiting list) delivered HRT/CBIT vs. waiting list: significantly greater reductions in clinician-rated and parent-reported tic severity in CBIT-VoIP relative to waitlist. One- third (n = 4) were considered treatment responders. Behavioral Treatment Idea and Evidence Recommendation historical background Study Number of Participants Results Exposure and Response Tics are Randomized control studies First line recommendation Prevention (ERP) conditioned according to [1] responses to Verdellen et al., 2004 9 n=43 (22 HRT, 21 HRT vs. ERP: significant urges exposure and response improvement for both prevention) groups (both methods are similarly effective).

Table e-2: Summary of randomized control studies of first-line behavioral therapies in primary tic disorders.

References: 1. Verdellen C, van de Griendt J, Hartmann A, Murphy T, Group EG. European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Part III: behavioural and psychosocial interventions. European child & adolescent psychiatry 2011;20:197-207. 2. Murphy TK, Lewin AB, Storch EA, Stock S, American Academy of C, Adolescent Psychiatry Committee on Quality I. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with tic disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2013;52:1341- 1359. 3. Steeves T, McKinlay BD, Gorman D, et al. Canadian guidelines for the evidence-based treatment of tic disorders: behavioural therapy, deep brain stimulation, and transcranial magnetic stimulation. Canadian journal of psychiatry Revue canadienne de psychiatrie 2012;57:144-151. 4. Azrin NH, Nunn RG, Frantz SE. Habit reversal vs. Negative practice treatment of nervous tics. Behavior Therapy 1980;11:169–178. 5. Azrin NH, Peterson AL. Treatment of Tourctte syndrome by habit reversal: A waiting list control group comparison. Behavior Therapy 1990;21:305–318. 6. O'Connor; K, Gareau; D, Borgeat F. A Comparison of a Behavioural and a Cognitive-Behavioural Approach to the Management of Chronic Tic Disorders. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 1997;4:105–117. 7. O'Connor KP, Brault M, Robillard S, Loiselle J, Borgeat F, Stip E. Evaluation of a cognitive-behavioural program for the management of chronic tic and habit disorders. Behaviour research and therapy 2001;39:667-681. 8. Wilhelm S, Deckersbach T, Coffey BJ, Bohne A, Peterson AL, Baer L. Habit reversal versus supportive psychotherapy for Tourette's disorder: a randomized controlled trial. The American journal of psychiatry 2003;160:1175-1177. 9. Verdellen CW, Keijsers GP, Cath DC, Hoogduin CA. Exposure with response prevention versus habit reversal in Tourettes's syndrome: a controlled study. Behaviour research and therapy 2004;42:501-511. 10. Deckersbach T, Rauch S, Buhlmann U, Wilhelm S. Habit reversal versus supportive psychotherapy in Tourette's disorder: a randomized controlled trial and predictors of treatment response. Behaviour research and therapy 2006;44:1079-1090. 11. Piacentini J, Woods DW, Scahill L, et al. Behavior therapy for children with Tourette disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Jama 2010;303:1929-1937. 12. Wilhelm S, Peterson AL, Piacentini J, et al. Randomized trial of behavior therapy for adults with Tourette syndrome. Archives of general psychiatry 2012;69:795-803. 13. Himle MB, Freitag M, Walther M, Franklin SA, Ely L, Woods DW. A randomized pilot trial comparing videoconference versus face-to-face delivery of behavior therapy for childhood tic disorders. Behaviour research and therapy 2012;50:565-570. 14. Seragni G, Chiappedi M, Bettinardi B, et al. Habit Reversal Training in children and adolescents with chronic tic disorders: an Italian randomized, single blind, pilot study. Minerva pediatrica 2015. 15. McGuire JF, Piacentini J, Scahill L, et al. Bothersome tics in patients with chronic tic disorders: Characteristics and individualized treatment response to behavior therapy. Behaviour research and therapy 2015;70:56-63. 16. Yates R, Edwards K, King J, et al. Habit reversal training and educational group treatments for children with tourette syndrome: A preliminary randomised controlled trial. Behaviour research and therapy 2016;80:43-50. 17. Ricketts EJ, Goetz AR, Capriotti MR, et al. A randomized waitlist-controlled pilot trial of voice over Internet protocol-delivered behavior therapy for youth with chronic tic disorders. Journal of telemedicine and telecare 2016;22:153-162.