Principles of Issuing Fatw” (Uÿ'l Al-Ift”) in the Hanafi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conditions of a Valid Custom in Islamic and Common Laws

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 3 No. 4 [Special Issue - February 2012] Conditions of a Valid Custom in Islamic and Common Laws Hafiz Abdul Ghani Assistant Professor of Religious Studies Forman Christian College (A Chartered University) Lahore, Pakistan Abstract This research paper highlights different kinds of customs and conditions for the validity of a legal custom in Islamic Sharī’a and common law. Both Islamic and the Western Jurisprudences have accepted custom and usages as an important sources of law. There is hardly any aspect of Islamic and English Jurisprudences where customary laws do not make their presence felt. From the individual to the international level, the use of customs in legal injunctions is a proven and undeniable fact. In social interaction, customs and usages encompass all these matters of every day life: inheritance, marriage, divorce, dowry, guardianship, adulthood, family ties, will, property, bestowal, division, religious rituals and adoption of a child. It is true that ‘urf and ‘ādat cannot attain the status of law unless they are supported by some political authority. But this is also a fact – and an undeniable fact – that, in the beginning, customs and usages as well as moral values acquired the status of laws. Key Words: Custom, Usage, ‘Urf , Ādat, sharī‘a, Law, jurisprudence Introduction Custom and usage are two technical terms of English jurisprudence which are known in Islamic jurisprudence as Literally and technically, these terms differ but in usage in society they overlap each .(عاده) and Ādah(عشف) Urf‘ other. In Islamic Law the definition of custom is stated as follows: “‘Urf or ‘ādah is (a state) which is firmly established in hearts and appeals one logically. -

Tradition, Change and Social Reform in the Fatwas of the Imam Muhammad 'Abduh

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-26-2017 Tradition, change and social reform in the fatwas of the Imam Muhammad 'Abduh Malak Tewfik Badrawi The American University in Cairo Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Badrawi, M. T. (2017).Tradition, change and social reform in the fatwas of the Imam Muhammad 'Abduh [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/1438 MLA Citation Badrawi, Malak Tewfik. Tradition, change and social reform in the fatwas of the Imam Muhammad 'Abduh. 2017. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/1438 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. School of Humanities and Social Sciences Tradition, Change and Social Reform in the Fatwas of the Imām Muhammad ‘Abduh A Thesis submitted to ARIC Arabic and Islamic Civilizations in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Malak Tewfik Badrawi (under the supervision of Dr. Mohamed Serag) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am very grateful to Dr. Mohamed Serag for his guidance. I would like to thank Mr. Yasser Mohammed Isma‘il for helping me with some of the Arabic terminology, and Dr. ‘Abd el-Wahid Nabawi and Mme Nadia Moustafa at Dar al-Watha’iq al- Qawmiya for their kindness. -

The Central Islamic Lands

77 THEME The Central Islamic 4 Lands AS we enter the twenty-first century, there are over 1 billion Muslims living in all parts of the world. They are citizens of different nations, speak different languages, and dress differently. The processes by which they became Muslims were varied, and so were the circumstances in which they went their separate ways. Yet, the Islamic community has its roots in a more unified past which unfolded roughly 1,400 years ago in the Arabian peninsula. In this chapter we are going to read about the rise of Islam and its expansion over a vast territory extending from Egypt to Afghanistan, the core area of Islamic civilisation from 600 to 1200. In these centuries, Islamic society exhibited multiple political and cultural patterns. The term Islamic is used here not only in its purely religious sense but also for the overall society and culture historically associated with Islam. In this society not everything that was happening originated directly from religion, but it took place in a society where Muslims and their faith were recognised as socially dominant. Non-Muslims always formed an integral, if subordinate, part of this society as did Jews in Christendom. Our understanding of the history of the central Islamic lands between 600 and 1200 is based on chronicles or tawarikh (which narrate events in order of time) and semi-historical works, such as biographies (sira), records of the sayings and doings of the Prophet (hadith) and commentaries on the Quran (tafsir). The material from which these works were produced was a large collection of eyewitness reports (akhbar) transmitted over a period of time either orally or on paper. -

Common Law Marriage, Zawag Orfi and Zawaj Misyar

4 Journal of Law & Social Research (JLSR) Vol.1, No. 1 ‘Urf’ And Custom In Common Law And Islamic Law: Common Law Marriage, Zawag Orfi And Zawaj Misyar Muhammad Khalid Masud1 Islamic legal tradition is discursive; it developed through discourses at two levels, one between jurists and society, and the other between jurists and state. The part played by differences of opinion (Ikhtilaf) and juristic reasoning (Ijtihad) cannot be overstressed. It provided strong basis for legal pluralism and accommodation of social practices, especially in the area of marriage and divorce. State efforts to centralize law did not meet the approval of the jurists. Since state had no direct role in the development of fiqh, the systematization of Fiqh and Law Schools was achieved through consensus. Looking back at the history of Islamic law, we find that local practices in various cities like Medina and Kufa generated diverse legal doctrines and gradually produced more than nineteen schools of law (madhhab); about seven are still in practice today. The distinct mark of the development of fiqh in this period is the diversity of views among the jurists on almost each and every doctrine. This diversity was welcomed by Islamic legal theory as a valid manifestation of Ijtihad. It is typically usual in the Fiqh texts to mention more than one view on almost every point. This is evident even in Fiqh texts like Fatawa Alamgiri, which were designed as a guide book for the qadis. Instead of giving just one doctrine of law, these texts refer to different opinions. It looks strange, but the underlying concept seems to be that it was not for the jurist, to choose between these varying opinions. -

Iraq Tribal Study – Al-Anbar Governorate: the Albu Fahd Tribe

Iraq Tribal Study AL-ANBAR GOVERNORATE ALBU FAHD TRIBE ALBU MAHAL TRIBE ALBU ISSA TRIBE GLOBAL GLOBAL RESOURCES RISK GROUP This Page Intentionally Left Blank Iraq Tribal Study Iraq Tribal Study – Al-Anbar Governorate: The Albu Fahd Tribe, The Albu Mahal Tribe and the Albu Issa Tribe Study Director and Primary Researcher: Lin Todd Contributing Researchers: W. Patrick Lang, Jr., Colonel, US Army (Retired) R. Alan King Andrea V. Jackson Montgomery McFate, PhD Ahmed S. Hashim, PhD Jeremy S. Harrington Research and Writing Completed: June 18, 2006 Study Conducted Under Contract with the Department of Defense. i Iraq Tribal Study This Page Intentionally Left Blank ii Iraq Tribal Study Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CHAPTER ONE. Introduction 1-1 CHAPTER TWO. Common Historical Characteristics and Aspects of the Tribes of Iraq and al-Anbar Governorate 2-1 • Key Characteristics of Sunni Arab Identity 2-3 • Arab Ethnicity 2-3 – The Impact of the Arabic Language 2-4 – Arabism 2-5 – Authority in Contemporary Iraq 2-8 • Islam 2-9 – Islam and the State 2-9 – Role of Islam in Politics 2-10 – Islam and Legitimacy 2-11 – Sunni Islam 2-12 – Sunni Islam Madhabs (Schools of Law) 2-13 – Hanafi School 2-13 – Maliki School 2-14 – Shafii School 2-15 – Hanbali School 2-15 – Sunni Islam in Iraq 2-16 – Extremist Forms of Sunni Islam 2-17 – Wahhabism 2-17 – Salafism 2-19 – Takfirism 2-22 – Sunni and Shia Differences 2-23 – Islam and Arabism 2-24 – Role of Islam in Government and Politics in Iraq 2-25 – Women in Islam 2-26 – Piety 2-29 – Fatalism 2-31 – Social Justice 2-31 – Quranic Treatment of Warfare vs. -

The Middle Grounds of Islamic Civilisation: the Qur’Ānic Principle of Wasaṭiyyah

The Middle Grounds of Islamic Civilisation: The Qur’ānic Principle of Wasaṭiyyah Mohammad Hashim Kamali1 Abstract: Is there such a thing as ‘moderate Islam’, and if so, what form does it take? The events of September 11, 2001, and the subsequent Global War on Terror have led scholars to debate this issue intensively. This article proposes that the principle of ‘Wasaṭiyyah’ or moderation and balance may provide the key to a better understanding of Islam and inter-civilisational relations. Reference is made not only to canonical Islamic scriptures but also to the work of Islamic scholars and commentators throughout the ages. Introductory Remarks Wasaṭiyyah (or the principle of moderation and balance) is an important but somewhat neglected aspect of Islamic teachings that has wide-ranging ramifications in almost all areas concerning Islamic civilisation. ‘Moderation’ as defined here is a moral virtue relevant not only to personal conduct but also to the integrity and self-image of communities and nations. It is an aspect of the self-identity and worldview of the ummah that is also valued in all major religions and civilisations. Moderation is a virtue that helps to develop social harmony and equilibrium in human relations. Despite its obvious advantages, one frequently notes that it is neglected not only in the personal conduct of individuals but also in social relations, religious practices and international affairs. The need for wasaṭiyyah has acquired renewed significance in the pluralist societies of our times, especially in light of the ‘clash 1. Mohammad Hashim Kamali is Chairman and CEO of the International Institute of Advanced Islamic Studies. -

The Political Ideology of Ayatollah ʿali Hosseini Khamenei

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Out of the Mouth of the Leader: The Political Ideology of Ayatollah ʿAli Hosseini Khamenei, Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Islamic Studies by Yvette Hovsepian Bearce 2013 © Copyright by Yvette Hovsepian Bearce 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Out of the Mouth of the Leader: The Political Ideology of Ayatollah ʿAli Hosseini Khamenei, Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran by Yvette Hovsepian Bearce Doctor of Philosophy in Islamic Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Leonard Binder, Chair The political ideologies of Ayatollah ʿAli Hosseini Khamenei, Supreme Leader of Iran, are identified and analyzed based on 500 speeches (1989-2013), 100 interviews (1981-1989), his biography and other works published in Iran. Islamic supremacy, resistance to foreign powers, and progress are the core elements of his ideology. Several critical themes emerge that are consistently reflected in the formation of his domestic and foreign policies: America, Palestine, Israel, Muslim unity, freedom, progress, the nuclear program, youth, and religious democracy. Khamenei’s sociopolitical development is examined in three critical phases: In Phase I, prior to the revolution, he is seen as a political activist protesting for an Islamic government; factors shaping his early political ideology are evaluated. Phase II examines Khamenei’s post- ii revolutionary appointments and election to president; he governs the country through the eight- year Iraq-Iran war. After the death of the father of the revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini, Khamenei enters into Phase III when he assumes the office of supreme leadership; internal and external issues test and reveal his political ideologies. -

Proquest Dissertations

Imam Kashif al-Ghita, the reformist marji' in the Shi'ah school of Najaf Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Abbas, Hasan Ali Turki, 1949- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 13:00:20 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/282292 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter &ce, while others may be from aity type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Following Sayyida Zaynab: Twelver Shi'ism in Contemporary Syria

Following Sayyida Zaynab: Twelver Shi‘ism in Contemporary Syria by Edith Andrea Elke Szanto Ali-Dib A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for the Study of Religion University of Toronto © Copyright by Edith Szanto, 2012 Following Sayyida Zaynab: Twelver Shi‘ism in Contemporary Syria Edith Szanto Ali-Dib Doctor of Philosophy Centre for the Study of Religion University of Toronto 2012 Abstract Outsiders, such as Lebanese and Syrian Shi‘is often refer to Twelver Shi‘is in the Syrian shrine-town as ‘traditional,’ and even ‘backward.’ They are not the only ones. Both Saddam Hussein and Ayatollah ‘Ali Khamenei have called the bloody flagellation practices, which have only increased in popularity in Sayyida Zaynab over the past few decades, ‘backward’ and ‘irrational.’ Why do these outsiders condemn these Twelver Shi‘is and their Muharram rituals? Why are ‘traditional’ practices popular in the Syrian shrine-town of Sayyida Zaynab? What does ‘tradition’ mean in this context? This dissertation begins with the last question regarding the notion of ‘tradition’ and examines seminary pedagogy, weekly women’s ritual mourning gatherings, annual Muharram practices, and non-institutionalized spiritual healing. Two theoretical paradigms frame the ethnography. The first is Talal Asad’s (1986) notion that an anthropology of Islam should approach Islam as a discursive tradition and second, various iterations of the Karbala Paradigm (Fischer 1981). The concepts overlap, yet they also represent distinct approaches to the notion of ‘tradition.’ The overarching argument in this dissertation is that ‘tradition’ for Twelver Shi‘is in Sayyida Zaynab is not only a rhetorical trope but also an intimate, inter-subjective practice, which ties pious Shi‘i to the members of the Family of the Prophet. -

Islam Advocates Moderation.Pdf

Islam advocates moderation Published in: New Straits Times, Monday 7 December 2015 By Professor Mohammad Hashim Kamali I MAY begin by posing a question: Are there any indicators to tell us that Islam anchors itself in the middle path of moderation, to show, in other words, that wasatiyyah is the governing principle of Islam? Islam’s advocacy of wasatiyyah is, first of all, known by the explicit affirmation of the Quran that designates the Muslim community as a community of the middle path (ummatan wasatan) (Al-Baqarah, 2:143). This Quranic designation is espoused with a commitment for the ummah to act as witnesses for truth and serve the cause of justice. Justice is the closest synonym for wasatiyyah, and a great virtue in its own right; it is a major theme of the Quran and a principal assignment of government in Islam. Wasatiyyah without justice would be an empty concept, yet justice too must be anchored in wasatiyyah: A judge can be inclined toward severity, or the opposite of that, and is thus advised to observe moderation in the delivery of justice. Islam’s commitment to the middle path of wasatiyyah is also manifested in mutual recognition (ta’aruf) — Q 49:13). The ummah builds its relationships with other communities and nations in the spirit of ta’aruf that nurtures friendship and peaceful co-existence. One of the manifestations of ta’aruf in Islam is the recognition of Christianity and Judaism as valid religions. Muslim jurists have by analogy extended the same status to the followers of other faiths and communities that reside in Muslim territories, and those who become non-Muslim citizens of a Muslim state. -

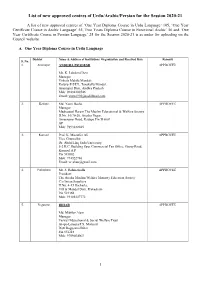

List of New Approved Centres of Urdu/Arabic/Persian for the Session 2020-21

List of new approved centres of Urdu/Arabic/Persian for the Session 2020-21 A list of new approved centres of ‘One Year Diploma Course in Urdu Language’ 105, ‘One Year Certificate Course in Arabic Language’ 55, Two Years Diploma Course in Functional Arabic’ 56 and ‘One Year Certificate Course in Persian Language’ 25 for the Session 2020-21 is as under for uploading on the Council website. A. One Year Diploma Course in Urdu Language District Name & Address of Institution / Organization and Received Date Remark S. No. 1. Anantapur ANDHRA PRADESH APPROVED Ms. K. Lakshmi Devi Manager Vishala Mahila Mandali Koturu-515571, Tanakallu Mandal, Anantapur Distt, Andhra Pradesh Mob: 09494200546 Email: [email protected] 2. Kadapa Md. Yasin Basha APPROVED Manager Madrasatul Haram The Muslim Educational & Welfare Society D.No. 10/70-20, Ayesha Nagar, Ameenpeer Road, Kadapa Pin 516001 AP Mob: 7893822045 3. Kurnool Prof. K. Muzaffer Ali APPROVED Vice Chancellor Dr. Abdul Haq Urdu University 5-2 K.C. Building Opp. Commercial Tax Office, Gooty Road, Kurnool A.P. Pin 518002 Mob: 994922786 Email: [email protected] 4. Prakasham Mr. S. Rahmathulla APPROVED President The Aiesha Muslim Welfare Minority Education Society C/o Imran Suppliers H.No. 4-15 Racharla, Vill & Mandal Distt. Prakasham Pin 523368 Mob: 94405337772 5. Begusarai BIHAR APPROVED Md. Mahfuz Alam Manager Parwaz Educational & Social Welfare Trust At+po Laruara P.S. Mofassil Distt Begusarai Bihar Pin 851218 Mob: 9709604063 1 6. Gaya Mr. Zakir Hussain APPROVED Manager Jamia Nooria Mojahide Millat, Aliganj, Road No. 4, Gaya Bihar Pin 823001 Mob: 9431223131 7. -

Towards a Solution Concerning Female Genital Mutilation?

JENS KUTSCHER Towards a solution concerning female genital mutilation? An approach from within according to Islamic legal opinions Introduction I don’t need my razor blades anymore . A few years ago to say that was unthinkable. No woman spoke about what happened during circumci- sion. They said our stomachs would swell and burst if we did. But nobody was actually harmed. I’m not afraid anymore to speak up. I was maybe thirteen years old when I became a circumciser. For me that was a chance to learn something . I didn’t pity the girls. To us the pain was a test. We can show that we are strong and courageous. When the girls have babies themselves later on, they have to endure the pain as well. I also circum- cised my three daughters myself. Because I love them. Only through circumcision do girls become real women; an uncircumcised woman is considered dirty and debauched—that’s what tradition has taught us, I’ve never doubted it . All of a sudden they said our tradition was wrong . Even the imam in the mosque said that we circumcisers are unworthy; there’s nothing in the Quran about circumcision. I was confused. Have I believed in an illusion all my life? (Translated from Fofanah & Heimbach 2010: 54.)1 1 Meine Rasierklingen brauche ich nicht mehr. […] Das war vor ein paar Jahren noch unmöglich. Keine Frau sagte, was bei einer Beschneidung passiert. Es hieß, unser Bauch würde sonst anschwellen und platzen. Aber niemandem ist etwas passiert. Ich habe keine Angst mehr zu sprechen.