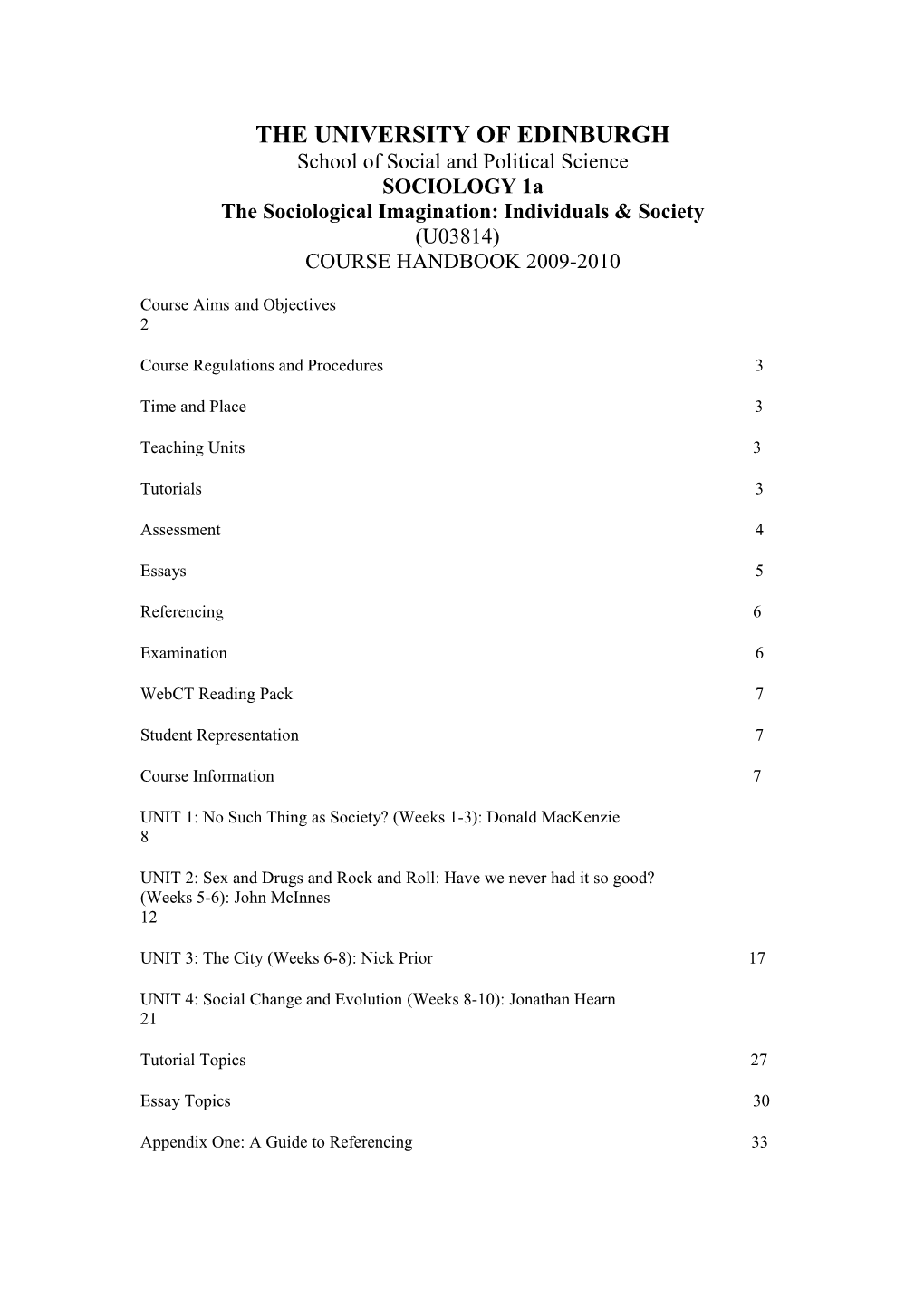

THE UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH School of Social and Political Science SOCIOLOGY 1a The Sociological Imagination: Individuals & Society (U03814) COURSE HANDBOOK 2009-2010

Course Aims and Objectives 2

Course Regulations and Procedures 3

Time and Place 3

Teaching Units 3

Tutorials 3

Assessment 4

Essays 5

Referencing 6

Examination 6

WebCT Reading Pack 7

Student Representation 7

Course Information 7

UNIT 1: No Such Thing as Society? (Weeks 1-3): Donald MacKenzie 8

UNIT 2: Sex and Drugs and Rock and Roll: Have we never had it so good? (Weeks 5-6): John McInnes 12

UNIT 3: The City (Weeks 6-8): Nick Prior 17

UNIT 4: Social Change and Evolution (Weeks 8-10): Jonathan Hearn 21

Tutorial Topics 27

Essay Topics 30

Appendix One: A Guide to Referencing 33 Appendix Two: Submitting your essay electronically 35

Appendix Three: Sample Examination Paper 36

Appendix Four: Essay Assessment Form 37

Appendix Five: Guide to Tutorial Sign-Up Using WebCT 38

Appendix Six: SSPS Common Essay Marking Descriptors 39

2 Welcome to Sociology 1a

This course is designed to introduce you to some of the key ideas of the discipline of sociology by examining the relationship between ‘individuals’ and ‘societies’. The course explores how wider social processes shape individual lives and how changes that occur around us influence our sense of self. The course therefore stresses the importance of sociological perspectives oriented around understanding the role of social order (Unit 1) and social change (Unit 4). How these perspectives aid our understanding of contemporary culture and ‘the city’ and their impact upon social relations is the focus of Units 2 and 3 respectively.

Course Organiser: Dr Nick Prior, Office Hours: Thursdays 10.00-12.00. Office: Room 6.20, Chrystal Macmillan Building, Phone: 650-3991; [email protected]

Senior Tutor: Emre Tarim, [email protected]. Please email if you require information or an appointment.

Course Secretary: Katie Teague. Office: Room G.04/G.05, Chrystal Macmillan Building, Phone: 650-4001; [email protected]

Course Aims and Objectives Aims This introductory course has four broad aims and four objectives: 1. It is an introduction to the discipline of sociology particularly for those with little or no previous systematic experience of it. The course both ‘stands alone’ for those for whom it is their only exposure to the subject and also provides a basis for further study – Sociology 1b, Sociology 2 and eventually joint or single Honours. 2. It is an introduction to key sociological themes, especially the link between individuals and society. 3. It will allow individual students to locate themselves in society and so develop an understanding of themselves in sociological terms. Students should be able to relate biography to social structure, and to realise that while they make their own lives it is not always in circumstances of their own choosing. 4. It will give students a flavour of several substantive topics of sociological analysis, their definition, investigation and presentation.

Objectives By the end of the course, students should be able to:

1. Show an understanding of key sociological concepts such as self, groups, institutions, social class, social change and gender. 2. Give an account of the changing nature of social life in modern societies. 3. Recognise and understand the processes by which social groups, whether small scale or organised at a macro, affect our attitudes and behaviour. 4. Develop an introductory understanding of the relationship between sociological argument and evidence.

3 Course Regulations and Procedures

Both Sociology 1a and 1b are taught within the School of Social and Political Science. You must read this current booklet in conjunction with the Social and Political Studies Student Handbook as all the regulations detailed there apply to this course. Here we outline either aspects that are specific to this course or matters that are so essential that they deserve to be repeated. Keep this manual safe: it acts as a kind of contract between you and us. We shall expect you to know what it contains.

Time and Place Lectures: Tuesday and Friday, 14.00-14.50, George Square Lecture Theatre.

NB: lectures will start promptly at 14.00 so please be seated by that time.

Teaching Units Please email the relevant member of staff to arrange an appointment if required.

No Such Thing as Society? Unit 1 Donald MacKenzie, [email protected], Weeks 1-3 Room 6.26, Chrystal Macmillan Building

Sex and Drugs and Rock and Roll: Have we never had it so Unit 2 good? Weeks 4-5 John MacInnes, [email protected], Room 2.05 8 Buccleuch Place

The City Unit 3 Nick Prior, [email protected], Weeks 6-8 Room 6.24 Chrystal Macmillan Building

Unit 4 Social Change and Evolution: Weeks 8-10 Jonathan Hearn, [email protected], Room 6.29 Chrystal Macmillan Building

Tutorials Tutorial attendance and the prompt submission of coursework are requirements for all students. Students who fail to attend at least seven out of ten tutorials without good reason will have their final mark reduced by one percentage point for each unapproved absence above the threshold, and will not have their final marks raised if their performance overall is borderline.

4 Please note that pressure of work or problems of time management are not considered an acceptable reason for non-attendance at tutorials or for late submission of work. Tutorial Sign-Up Tutorial sign-up is done online, using WebCT. Full instructions on how to do this are available in Appendix 5 of this booklet. You must sign up for a tutorial by Friday 25th September (the end of Week 1) or you will be randomly assigned to a group.

Tutorials will be held weekly in weeks 2-10. Week 11 is for revision.

Assessment Please visit the following page for detailed clarification on all coursework and assessment regulations: http://www.sps.ed.ac.uk/undergrad/year_1_2/assessment_and_regs/coursework_requirements

Our aim in assessment is to encourage students to cover a wide range of the themes raised through reading, discussion and writing, and to examine knowledge of the course materials. With this in mind, we seek to differentiate each item of assessment, and to minimise the extent to which it is possible to pass the course by focussing excessively on just one or two elements.

One essay and a two-hour degree examination constitute the assessment for the course. In order to pass Sociology 1a you must achieve an overall mark of at least 40%. This mark is based on a weighted combination of essay and exam marks – see below. You must also achieve a mark of at least 40% in the exam. In order to proceed to Sociology Honours, a pass mark of at least 50% overall must be achieved in Sociology 2, Social and Political Theory 2h and Social and Political Enquiry 2h.

Sociology uses the University’s extended common marking scheme (see Appendix 6). Marks for essays and examinations are totalled separately.

Your final mark will be made up as follows: Your essay contributes 40% and the Degree Examination contributes the remaining 60%.

The essay and examination script of any candidate falling on a margin (e.g. between passing and failing, or at a merit border) will be seen additionally by the external examiner before the final mark is awarded at the examiners' meeting in late May 2008. There is no fixed percentage of passes or of merits.

The most common cause of failure is that students do not complete the course- work or do not attend the examination. All students who fail the course must take the re-sit examination in August 2010. Visit the following site for details: http://www.sps.ed.ac.uk/undergrad/year_1_2/assessment_and_regs/examination_requi rements

5 Essays You must submit one essay for this course. See page 30 for essay topics, and readings. Your essay must be no more than 1500 words. Essays which are over- length will be penalised (please see SSPS School handbook for further details).

You must upload an electronic copy of your essay onto WebCT, as well as submitting ONE hard copy to the essay box by 3pm on the day of deadline. See Appendix 2 at the back of this booklet for further information.

There are formal procedures for requesting an extension and penalties apply for late essays submitted without formal approval. The penalty will be a reduction by five marks per working day (i.e. excluding weekends) for up to five days. Please note that the daily boundary is 3pm as per the deadline. For work handed in more than five days late a mark of zero will be recorded. Check here for full details on electronic submission penalties: http://www.sps.ed.ac.uk/undergrad/year_1_2/assessment_and_regs/coursework_requi rements

If you have good reason for not meeting a coursework deadline, you may request an extension before the deadline, either from your tutor (for extensions up to five working days) or the course organiser (for extensions of six or more working days), normally before the deadline. The tutor or course organiser must support the request in writing (email) to the Undergraduate Teaching Officer (UTO), and extensions over five working days may require supporting evidence. If you think you will need a longer extension or your reasons are particularly complicated or of a personal nature, you should discuss the matter with your Director of Studies. We may ask him/her to confirm that you have done so before granting an extension. In fairness to other students, permission to submit an essay more than two weeks after the due date will be very rare, and will only be agreed where compelling mitigating circumstances are provided via your Director of Studies.

Coursework submission dates:

Essay Deadline - 3pm, Friday 6th November 2009 (Week 7)

Essays must be put into the essay pod OUTSIDE G04/05, Chrystal Macmillan Building before the 3pm deadline. A School coursework cover sheet which will be provided outside room G04/05 should also be attached.

We aim to give you your provisional result with appropriate comments within three weeks of submission, if handed in on time.

Avoiding Plagiarism:

6 Material you submit for assessment, such as your essays, must be your own work. You can and should draw upon published work, ideas from lectures and class discussions, and (if appropriate) even upon discussions with other students, but you must always make clear that you are doing so. Passing off anyone else’s work (including another student’s work or material from the Web or a published author) as your own is plagiarism and will be punished severely. You will be asked to sign a declaration attached to the front sheet of the essay stating that the work is your own and the electronic copy of your essay will be submitted to ‘Turnitin’, our plagiarism detection software. Assessed work that contains plagiarised material will be awarded a mark of zero, and serious cases of plagiarism will also be reported to the University's Discipline Committee. In either case, the actions taken will be noted permanently on the student's record. For further details on plagiarism see the School of Social and Political Studies handbook or the school website.

Choosing Appropriate Language: The language we use to write about social life can hide some very problematic assumptions. The British Sociological Association has published useful guidelines on the way language can easily reflect racist and sexist views of the world. The gist of our advice is that you should never use male nouns and pronouns when you are referring to people of both sexes (use a plural ‘they’, ‘their’ or think of a different way to phrase your argument; or use ‘s/he’, ‘his/her’). You should also never use language which suggests that human races exist with distinct biologies, nor language which suggests that people disabled in some way are less than full members of society. You should also check the geographical dimension: for example is your source based on data from Britain, or only from England and Wales?

Referencing Adequate referencing is an important academic skill that we want all our students to learn. Your essays MUST include a list of references at the end. For the appropriate format, check one of the major Sociology journals held in the Library such as The British Journal of Sociology. If in doubt, consult your tutor. Points may be deducted for essays where the referencing is not well done. See appendix 1 for further information about referencing.

Examination

There are no “class examinations” in Sociology and there are no exemption arrangements.

Sociology 1a will have a two hour examination in December. You will be required to answer two questions.

In order to ensure that you have learned material from the second two units of the course, the examination will be divided into two sections, corresponding to the third and fourth units of the course and you will be required to answer one question from each section.

You must pass the examination (with a grade of 40% or above) to pass the course.

7 The examination marks contribute 60% of the overall assessment.

A copy of last year’s December examination paper is at the end of this manual.

WebCT Readings We have assembled a course reading pack, some of which will be available on WebCT under the ‘Resources’ icon. This contains readings used in the tutorials. Some of these readings are either required or recommended for essay questions. There will be no hard copy of this reading pack available. Not all readings will be on WebCT but those that are are clearly marked as such in this handbook. Other readings will be available online or in the library.

Student Representation The Sociology Department welcomes student input into the management of the course and its assessment, and runs a Staff-Student Liaison Committee, on which Sociology 1a is entitled to three class representatives. Class representatives are chosen from a pool of tutorial representatives from each tutorial group, and this will be arranged during the first half of semester 1. Any problems with the course should first be raised with your tutor or with the course organiser, Nick Prior. We will also ask you to fill in an overall assessment form at the end of the course.

Course Information During the course of the year, all important information for the class will be announced in lectures. Information will also be posted on the notice boards outside the SSPS Undergraduate Teaching Office, room G04/05, CMB. Course handouts, overhead slides, details of class reps, etc. will be posted on the Sociology 1a webCT page. You should also remember to check your university and WebCT email accounts on a regular basis as this is the only way sociology staff will be able to contact you about course matters.

Timetable at a glance Week of Course Tuesday Lecture Friday Tutorial No: Notes Lecture Wk 1 22/09/09 25/09/09 No tutorial Tutorial sign-up

Wk 2 29/09/09 02/10/09 Tutorial 1

Wk 3 06/10/09 09/10/09 Tutorial 2

Wk 4 13/10/09 16/10/09 Tutorial 3

Wk 5 20/10/09 23/10/09 Tutorial 4

Wk 6 27/10/09 30/10/09 Tutorial 5

Wk 7 03/11/09 06/11/09 Tutorial 6 Essay Due

Wk 8 10/11/09 13/11/09 Tutorial 7

Wk 9 17/11/09 20/11/09 Tutorial 8

8 Wk 10 24/11/09 27/11/09 Tutorial 9

Wk 11 Revision Revision Revision

Wk 12 Exams

Wk 13 Exams Semester 1 ends 18/12/09

WEEK 1

Tuesday 22/09/09: Introductory Lecture: Nick Prior

An organisational lecture in which the main regulations and procedures of the course will be outlined and in which staff will introduce their units.

UNIT 1: No Such Thing as Society? (weeks 1-3): Donald MacKenzie

Books for Unit 1:

We’ll be using four main books: all are in the library in multiple copies (at least 12 of each). The two we’ll use most often are Michael Hechter and Christine Horne, Theories of Social Order: A Reader (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003) and John P. Hewitt, Self and Society: A Symbolic Interactionist Social Psychology (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2007).

For the tutorial in week 3, you’ll need to read Norah Vincent, Self-Made Man: My Year Disguised as a Man (London: Atlantic, 2006). Those choosing essay topic 2 will also need to make heavy use of Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (Edinburgh: Social Sciences Research Centre, 1956; published in the U.S. in 1959 by Doubleday Anchor; current publisher Penguin). It’s somewhat preferable to use one of the published editions, which are rather more explicit on some key points than Goffman’s original report.

To the extent permitted by copyright legislation, we’ve made key readings available electronically via WebCT. In the case of the authors in Hechter and Horne’s reader, these extracts are usually from the original version: look in WebCT for the name of the author of the extract.

Buying books: not compulsory, but we’ll be using Hewitt and especially Hechter & Horne quite a bit, and even books that are in the library in multiple copies can be hard to get hold of close to an essay deadline. So you might find it useful to buy either or both, and also Goffman if you are doing essay 2. We have asked Word Power (43-45 West Nicholson St.) and Blackwells (53-63 South Bridge) to stock all three.

‘No Such Thing as Society’?

Interviewed by Woman’s Own in 1989, Margaret Thatcher said: ‘And, you know, there is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women, and there are families’. The point she was making was political – that people shouldn’t be too

9 reliant on the state – but her remark is also a challenge to the very idea of sociology. It’s the discipline that studies ‘society’. But what is society? Does it really exist? Is it not simply a collection of individuals?

Unit 1 examines five answers to the question ‘what is society?’ a. That what we call ‘society’ is indeed simply a collection of individuals, each rationally seeking the maximum personal benefit; b. That ‘society’ is a set of roles (for example, ‘doctor’, ‘mother’, ‘student’), with associated ‘norms’ (the do’s and don’ts of social life) and values (e.g. ‘put your children first’); c. That ‘society’ is our susceptibility to each other, in particular our anticipation of how we will look in others’ eyes; d. That ‘society’ is a network of relationships amongst people who know each other personally; e. That ‘society’ is imitation, the way in which we do what others do and learn to like what they like.

We’ll touch on how to apply these ideas to some of life’s practical problems: how to be happy; how to be healthy; why as a country we’re putting on weight (but some people are dying of eating disorders). You’ll learn a means of predicting whether a marriage or other long-term relationship will last, and even a – scientifically-tested – tip for making yourself more attractive to others, including the opposite sex! Through matters such as this, we’ll explore the famous, if sexistly expressed, maxim from Aristotle’s Politics – ‘man is a social animal’ – and take a literal approach to the animality of human beings. We’ll have some fun, for example playing a game (for real money, which you can really take away with you) in the first lecture of the unit, and a further game – not, alas, for real money – in the first tutorial.

Two closely-related overall questions run through Unit 1:

1. ‘How can a collection of individuals manage to live together?’ (Hechter and Horne, Theories of Social Order, p. 27). This is what sociologists call ‘the problem of social order’. 2. What is the self? We’ll explore the ‘symbolic interactionist’ argument that the self is not an entity inside us, but ‘something named, to which attention is paid and toward which actions are directed’ (Hewitt, Self and Society, p. 76).

If either of those questions interests you, you can investigate further by choosing essay topic 1 or 2 from the list that you’ll find towards the end of this Handbook.

Friday 25/09/09: The Selfishly Rational Human and the Norm-Following Human

This lecture will examine two views of human beings: that they are self-seeking, rational individuals (see view a above) and that they follow norms and values (view b above).

Readings:

[WEBCT] Michael Hechter and Christine Horne, Theories of Social Order: A Reader

10 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003), pp. 3-8, 15-21, *22-24 [WEBCT], Weber, ‘Types of Social Action’, pp. 91-100.

[WEBCT] Leda Cosmides and John Tooby, ‘Cognitive Adaptation for Social Exchange’, in The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture, edited by J. H. Barkow, L. Cosmides, and J. Tooby (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), pp. 181-184.

WEEK 2

Tuesday 29/09/09: Norms, Roles and Social Order

This session continues our examination of the ‘selfishly rational’ view and (especially) the ‘norm-following’ view of human beings. We will elaborate the ‘norm-following’ view to take into account the fact that many norms are specific to particular social roles, begin our discussion of ‘social order’, and examine some causes of happiness, suicide and over-eating.

Readings:

[WEBCT] John P. Hewitt, Self and Society: A Symbolic Interactionist Social Psychology (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2007), pp. 59-66. [WEBCT] Michael Hechter and Christine Horne, Theories of Social Order: A Reader (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003), pp. *27-32, 91-100, *112–117 (Durkheim, ‘Egoistic Suicide’), *118-128 (Durkheim, ‘Anomic Suicide’), *170-173 (Hobbes, Leviathan) and *251-260 (Smith, ‘The Division of Labour’).

[WEBCT] Avner Offer, The Challenge of Affluence: Self-Control and Well-Being in the United States and Britain since 1950 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 28-30, 138-153.

Friday 02/10/08: The Self and Mutual Susceptibility

This session explores sociological views of the self, examines the way in which human beings are ‘mutually susceptible’ (strongly affected by how others regard them), and touches on the extent to which this explains why people cooperate even in situations in which it is individually costly for them to do so.

Readings:

[WEBCT] John P. Hewitt, Self and Society: A Symbolic Interactionist Social Psychology (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2007), pp. 54-59, 66-69 and 111-113.

[WEBCT] Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (Edinburgh: Social Sciences Research Centre, 1956; or later editions), chapter one, ‘Performances’.

[WEBCT] Thomas J. Scheff, ‘Shame and Conformity: The Deference-Emotion

11 System’, American Sociological Review 53 (1988): 395-406. (WEBCT) Malcolm Gladwell, Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking (London: Allen Lane, 2005), pp. 18-34.

[WEBCT] Scott Barrett, Environment and Statecraft: The Strategy of Environmental Treaty-Making (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), pp. 3-5. (Please don’t read until after your tutorial in week 2.)

[WEBCT] Barry Barnes, The Elements of Social Theory (London: UCL Press, 1995), pp. 53-60.

WEEK 3

Tuesday 6/10/09: Social Networks and Social Capital

This session discusses the importance of networks of relationships amongst people who know each other personally, and of the patterns of ties in such networks. We will explore Putnam’s argument that the strength of social networks (an aspect of what is called ‘social capital’) is a crucial explanation of a wide range of phenomena, including health, happiness and prosperity.

Readings:

[WEBCT] Michael Hechter and Christine Horne, Theories of Social Order: A Reader (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003), pp. 283-290 and *299-309 (Granovetter, ‘Strength of Weak Ties’).

[WEBCT] Ronald S. Burt, Brokerage and Closure: An Introduction to Social Capital (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 10-19, 93-97 and 167-169.

[WEBCT] Robert Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York: Touchstone, 2001), pp. 18-19, 290-295 and 326-335.

Friday 09/10/09: Imitation

A powerful aspect of social behaviour is the propensity of human beings to imitate each other. In this session, we will examine the classic experiment on this topic by Solomon Asch. We will also discuss examples of the implications of imitation, including judgements of the attractiveness of the opposite sex, eating disorders and behaviour in the stock market.

Readings:

[WEBCT] Asch, S.E. 1951. ‘Effects of Group Pressure upon the Modification and Distortion of Judgments’. Pp. 177-190 in Groups, Leadership and Men, edited by H. Guetzkow. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Press.

12 [WEBCT] Benedict C. Jones, et al., ‘Social Transmission of Face Preferences Among Humans,’ Proceedings of the Royal Society B 274 (2007): 899-903.

[WEBCT] Mervat Nasser and Melanie Katzman, ‘Sociocultural Theories of Eating Disorders: An Evolution in Thought’. Pp. 139-150 in Handbook of Eating Disorders, edited by Janet Treasure, Ulrike Schmidt and Eric van Furth (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, second edition 2003).

[WEBCT] James Surowiecki, The Wisdom of Crowds (London: Little, Brown, 2004), pp. 3-22.

UNIT 2: Sex and Drugs and Rock and Roll: Have we never had it so good? (Weeks 4-5) John MacInnes

Donald’s lectures established the idea that there exists something we can think of as society that is more than just the sum of many different ‘individuals’. In this set of lectures I want to take our analysis of individual and society further by doing three things. First I’ll look at how individuals in contemporary societies, particularly young people, seem to enjoy much more personal freedom and autonomy than in the past. I’ll use the concept of fashion to do so. Second I’ll begin to look at two different kinds of relationship that might exist between the individual and society that might explain the rise of ‘fashion’ in its widest sense, and in particular look at the way sociology has tried to establish a key contrast between ‘traditional’ and ‘modern’ societies. This contrast is about social structure. Social structure is not always an easy concept to grasp, but concerns they way social relations and institutions get reproduced over time without anyone apparently having to consciously set out to do this. This will anticipate some of the arguments Jonathan Hearn will examine in Unit Four of this course. It raises the issue of personal agency: we might like to imagine that the decisions we make are personal and private ones, but often our behaviour is socially conditioned: even when we attempt (e.g. through the use of alcohol or other drugs) to ‘lose control’. Finally I’ll look at whether our apparently greater autonomy in contemporary Western societies in fact conceals various kinds of hidden constraints, rules and restrictions that are relatively invisible because they are largely self- imposed, and in a rather unconscious manner.

I’ll focus quite a bit on various aspects of the body, including the music we listen (and dance) to, how we dress (fashion), at some aspects of ‘plastic’ or recreational rather than reproductive sexuality and at how we get ‘out of our heads’ on legal or illegal intoxicants. As you might be aware, for example from science fiction films such as Matrix, it is possible to argue that in contemporary society our physical body is less and less relevant to most of our lives. Workers don’t need much muscle power if technology now does almost all the work of lifting, moving, digging, carrying etc. People need rely less on their own physical strength for their personal security in a society where the state can guarantee and police individual safety. In the age of nuclear and ‘smart’ weapons, enormous armies of fit, muscular men are something of an anachronism, despite what has recently happened in the Balkans, Afghanistan or Iraq. In an era of increasingly ‘equal rights’ possessing a male or female, black or

13 white body constrains us much less than in the past. In contemporary societies we ‘work’ more with our minds than our bodies. So how is it that these days our physical bodies seem to occupy so much more of our attention? I’ll suggest that we use them, consciously or not, as platforms to display our sense of identity a theme that the second year sociology course will return to.

WEEK 4

Tuesday 13/10/09: Mass Fashion: Modernity, Individual Autonomy and Identity

You almost certainly bought the clothes you are wearing. And you almost certainly imagined you were making some kind of personal statement when you bought them. But if fashion is all about individuality and personal expression, how can we explain fashions? In this class I’ll first distribute a brief questionnaire for you to fill up, and do a small group exercise on what we mean by fashion. ‘Fashion’ does not, at first sight, seem to be very important, but it does have five features that make this subject a very useful one for getting to grips with understanding how societies function. First any kind of fashion involves a curious tension between the assertion of individual uniqueness and autonomy on the one hand and observation of and submission to often very elaborate rules of presentation and behaviour on the other. Second, and allied to the first point, if we look at ‘fashions’ in the widest sense of the term – trends in music, deportment, dance, drug and alcohol use, language and recreation as well as dress – it seems as if these are used by successive generations, and ever smaller groups within them, to mark their distinctiveness. Third, fashion is always, by definition new, even, paradoxically, when it takes a ‘retro’ form. In this it mimics our contemporary world with its relentless stress on change and innovation. Fourth, although it may serve other ends (such as courtship or group membership) fashion as such is usually an end in itself: it has no ‘point’. Finally, only over the last century, and in very restricted parts of the world, has it become possible for any but a tiny minority to be ‘fashionable’. The rise of fashion thus tells us something about the rise of affluence, especially for a category of person who hardly existed until about fifty years ago: the teenager, or adolescent. This rapidly dating category corresponds to young people with sufficient resources to be consumers, and perhaps even live independently, but be relatively free of ‘adult’ responsibilities such as parenthood, marriage or a fixed career.

Readings:

[WEBCT] Ian Craib (1997) ‘Simmel on modernity’ in Classical Social Theory (Oxford University Press) pp. 169-171.

Georg Simmel ([1904] 1957). ‘Fashion’ in American Journal of Sociology, 62, 541- 548.

S. Asch (1955) ‘Opinions and Social Pressure’ in Sci Amer. Vol 193 Available at http://www.wadsworth.com/psychology_d/templates/student_resources/0155060678_ rathus/ps/ps18.html

Diana Crane (2000) ‘The Social Meanings of Hats and T-shirts’ from Fashion and Its Social Agendas: Class, Gender, and Identity in Clothing Univ of Chicago Press. Available at http://www.press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/117987.html

14 Further Readings:

Angela McRobbie 1994 ‘Second hand dresses and the role of the ragmarket’ in Postmodernism and Popular Culture, Routledge.

Elizabeth Wilson 1985 Adorned in Dreams, Virago.

Friday 16/10/09: Rock and Roll (and sex and drugs)

Sex and drugs and rock and roll Is all my brain and body need Sex and drugs and rock and roll Are very good indeed

Keep your silly ways or throw them out the window The wisdom of your ways, I've been there and I know Lots of other ways, what a jolly bad show If all you ever do is business you don't like

Every bit of clothing ought to make you pretty You can cut the clothing, grey is such a pity I should wear the clothing of Mr. Walter Mitty See my tailor, he's called Simon, I know it's going to fit

Here's a little piece of advice You're quite welcome it is free Don't do nothing that is cut price You know what that'll make you be They will try their tricky device Trap you with the ordinary Get your teeth into a small slice The cake of liberty Ian Dury (1942- 2000)

I’ll start this lecture with a very brief account of what sociologists mean when they speak about ‘modern’ society and then go on to look at another aspect of ‘fashion’ in its broadest sense: music. We tend to think of music in terms of personal taste, however I’ll argue that there are sound sociological reasons for why ‘rock and roll’ emerged when and where it did and in the form that it did. I’ll look (briefly) at Bill Haley and the Comets, Elvis, Bob Dylan and some more contemporary bands. To celebrate the fortieth anniversary of ‘the summer of love’ I’ll look (very briefly) at the relationship between rock and roll, sex and illicit drugs. If you go clubbing, it is often common to see men dancing, either alone, with each other or with a female partner. Forty years ago men rarely danced. Women danced together, and, if they were (un)lucky, a man, or pair of men, might venture onto the dance floor and ask them to dance. Why has this changed?

Readings:

[WEBCT] Andy Bennet Culture and Everyday Life Ch. 6 Music pp. 117 – 140.

15 [WEBCT] Karl Marx and Frederick Engels (1848) passage from The Communist Manifesto, various editions, for example in R.C. Tucker (ed) 1978, Marx-Engles Reader, Norton.

Walter Benjamin 1936 The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Available at http://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ge/benjamin.htm

Further Readings:

Merman, Marshall. All that is solid melts into air. The experience of modernity. London: Verso, 1993.

WEEK 5

Tuesday 20/10/09: Out of your head

The chances are that you have probably got ‘drunk’ or ‘high’ at some point in your life, if not within the last few days. However even when we ‘get out of it’ we tend to do this in highly socially organised ways, which change over time, often in close correspondence with changing fashions in music. I look at some of the fashions in drug and alcohol use, their relationship to ‘dance’ and other forms of movement and at how these have been related to other social changes. In doing so I’ll use what sociologists call ‘quantitative’ evidence, or some simple statistics presented in tables, and explain how to interpret them. Forty years ago, young men drank and smoked much more than their female peers, in part because until the 1976 Sexual Discrimination Act made it illegal, many pubs were for men only. Babycham became a very successful drink in part because women could order it in a bar and still be thought of as ‘respectable’. Gymns were either in schools or the odd sweaty den where boxers trained. How is it that what we do in our ‘free’ time has changed so much?

Readings:

[WEBCT] Harry G. Levine (1978) ‘The Discovery of Addiction: Changing conceptions of habitual Drunkeness in America’ Journal of Studies on Alcohol 15 493-506.

[WEBCT] Sheehan, Margaret and Ridge, Damien (2001) ‘“You Become Really Close…You Talk About The Silly Things You Did, And We Laugh”: The Role Of Binge Drinking In Female Secondary Students' Lives’, Substance Use & Misuse 36(3) 347 — 372.

Fiona Measham and Kevin Brain 2005 ‘‘Binge’ drinking, British alcohol policy and the new culture of intoxication’ in Crime Media Culture Vol 1. pp. 262-83. and at http://cmc.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/1/3/262

Handout on alcohol consumption statistics from the General Household Survey.

Further Readings:

16 Brain, Kevin, Parker, Howard and Carnwath, Tom (2000) 'Drinking with Design: young drinkers as psychoactive consumers', Drugs: education, prevention and policy, 7:1, 5 — 20.

Fiona Measham 2004 ‘The decline of ecstasy, the rise of ‘binge’ drinking and the persistence of pleasure’ in Probation Journal Vol 51; pp.309-326. and at http://prb.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/51/4/309

You can listen to Professor Laurie Taylor in conversation with Dr Measham at http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/factual/thinkingallowed/thinkingallowed_20060920.sht ml

Friday 23/10/09: The Full Monty

This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned towards the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress. (Walter Benjamin Illuminations London:Fontana 1992) p. 259 – 60)

In Britain, at least according to the poet Philip Larkin, sexual intercourse was invented in 1966. Particularly in Western Europe the last four decades have been ones of unprecedented and rapid sexual ‘liberalization’. Until the 1960s homosexuality, sexual relations outside marriage, non-reproductive forms of sexuality (e.g. oral sex) or the use of contraception and abortion were all either illegal or subject to very heavy normative repression. Standards of bodily display or the use of erotic or sexual imagery were also heavily restricted. For example only the 1959 Obscene Publications Act made possible the publication of D.H. Lawrence’s novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover because it contained the word ‘fuck’ and featured sexual relations between and aristocratic woman and lower class man. However, does this mean we now enjoy sexual ‘freedom’, or is even our most private and intimate sexual behaviour socially determined? If we think of the range of hedonistic pleasures, legal or illegal, available to us today it appears that we have reached new heights of individual freedom and autonomy. Liberated from the constraints and taboos of the past, it seems as if both men and women are freer than ever before to treat their bodies and senses as somatic playgrounds limited only by what they can afford, or dare, to do. Lifestyle magazines that fifty years ago might have printed recipes now mean something rather different by ‘dish of the day’ and both male and female readers are invited to explore various aspects of recreational sexuality that only a few decades ago would have been punishable by law in many western countries, and in many non- western countries still are. However, I’ll ask if our freedom to enjoy limitless fashion, in sex as in any other sphere, represents unqualified progress or rather a new form of social order characterised by rules and norms that may be different in form but are just as substantial as those we knew before. Why is it that the two fastest growing occupations in the Western World are security guards and therapists? the former controlling our physical space, while the latter might police our mental space. I’ll conclude by looking at the film the Full Monty and ask: where did we get the idea that taking your clothes off in public for money was liberating?

17 Readings:

[WEBCT] William H Sewell (1992) ‘A Theory of Structure’ in American Journal of Sociology 98(1)1-29.

Angela McRobbie 1999 ‘More! New sexualities in girls’ and women’s magazines’ (Ch 4), pp. 46 – 61 in In the culture society Routledge OR

Angela McRobbie 1999 ‘Pecs and penises the meaning of girlie culture’ (Ch 9), pp. 122-131 in In the culture society Routledge

A Giddens BBC Reith Lectures 1999 Lecture 4: ‘The family’. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/static/events/reith_99/week4/week4.htm

Further Readings:

Anthony Giddens 1991‘The tribulations of the self’ (Ch. 6) Modernity and Self Identity, Cambridge: Polity.

Anthony Giddens 1992 The Transformation of Intimacy, Cambridge: Polity Ulrich Beck and Elizabeth Beck-Gernsheim 1994 The Normal Chaos of Love Cambridge: Polity.

UNIT 3: The City (Weeks 6 – 8): Nick Prior

This unit argues that the birth of the modern city has transformed the way social life is experienced and is fundamental to the way we relate to one another. You can find useful overviews of the city as a topic of sociological analysis in the following three introductory texts. There are multiple copies in the Reserve section of the main library.

1) John Macionis and Ken Plummer, Sociology: A Global Introduction, Third Edition (Prentice Hall, 2005), chapter 23, “Populations, Cities and the Shape of Things to Come”. [NB: in the Fourth Edition, 2007, this has become chapter 24).

2) James Fulcher and John Scott, Sociology, Second Edition (Oxford University Press, 2003), chapter 13, “City and Community”.

18 3) Anthony Giddens, Sociology, Fifth Edition (Polity, 2006), chapter 21, “Cities and Urban Spaces”. [NB: in earlier editions, this chapter may fall under a different number].

WEEK 6

Tuesday 27/10/09: The Modern City and the Metropolitan Type

The city is a primary site of modern society. This session will assess some classic statements on the way the city impacts upon our experience and the possibility that urban environments produce particular personalities or social types.

Readings:

[WEBCT] Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life”, 1903, in On Individuality and Social Forms; extract from Roger Bocock and Kenneth Thompson (eds), Social and Cultural Forms of Modernity, Open University Press/Polity, 1992.

David Lee and Howard Newby, “Urbanism as a Way of Life”, chapter 3 of The Problem of Sociology (Hutchinson, 1987).

Friedrich Engels, “The Great Towns”, from The Condition of the Working Class in England, 1845, reprinted in Richard LeGates and Frederic Stout (eds), The City Reader (Routledge, 1996).

Deborah Stevenson, “Landscapes of Shadow and Fog: The Emergence of the Industrial City”, chapter 2 of Cities and Urban Cultures (Open University Press, 2003).

Robert Bocock and Kenneth Thompson, “Metropolis: The City as Text”, chapter 9 of Social and Cultural Forms of Modernity (Open University Press, 1992).

Deborah Stevenson, “Landscapes of Shadow and Fog”, chapter 2 of Cities and Urban Cultures (Open University Press, 2003).

Friday 30/10/09: Urbanism as a “Way of Life”

Here we focus on the Chicago School of sociology and its insights into the “urban personality”. Are urban relations warm or cold? What does Wirth mean when he says that urbanism is a “way of life”? Can we make sense of incidents like the “Kitty Genovese” murder case using the Chicago’s School’s ideas, or use such ideas to understand the collapse of civic engagement in contemporary society?

Readings:

19 [WEBCT] Louis Wirth, "Urbanism as a Way of Life", 1938, reprinted in The City Reader, edited by R. LeGates and F. Stout (Routledge, 1996).

“All about the Kitty Genovese Murder”, Mark Gado, http://www.crimelibrary.com/serial_killers/predators/kitty_genovese/1.html?sect=2

Robert D. Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (Simon and Schuster, 2000).

John Fulcher and John Scott, Sociology (Oxford University Press, 2003), pp494-506.

David Lee and Howard Newby, “Urbanism as a Way of Life?”, chapter 3 of The Problem of Sociology (Hutchinson, 1987).

Mike Savage and Allan Warde, “The Roots of Urban Sociology”, chapter two of Urban Sociology, Capitalism and Modernity (Macmillan, 1993).

Robert E. Park, “The City: Suggestions for the Investigation of Human Behaviour”, 1915, reprinted in chapter 3 of The Subcultures Reader, Kenneth Gelder and Sarah Thornton (eds) (Routledge, 1997).

Mike Savage and Allan Warde, Urban Sociology, Capitalism and Modernity (Macmillan, 1993).

WEEK 7

Tuesday 03/11/09: Urban Decline and the Death of Public Space

This session will continue to look at critiques of the modern city and the breakdown of social order, but this time focus on social inequalities, poverty and the decay of urban space. How do cities segregate rich and poor? What impact have recent social changes had on tolerance, welfare and diversity in the city? Has the growth of the rationalised city led to the decline of public space?

Readings:

[WEBCT] Mike Davis, “Fortress L.A.”, from City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles (Vintage, 1992), pp.221-263.

[WEBCT] Peter Marcuse, “Cities in Quarters”, extract from A Companion to the City, Gary Bridge and Sophie Watson (eds) (Blackwell, 2003).

Deborah Stevenson, “Cities of Difference: Inequality, Marginalization and Fear”, chapter 3 of Cities and Urban Cultures, (Open University Press) 2003.

Richard Rogers, “This is Tomorrow”, Independent on Sunday, 23rd November, 1997, pp.10-16.

Richard Sennett, “The Public Domain”, chapter 1 of The Fall of Public Man (Faber and Faber, 1974).

20 “Miles better – or miles apart?”, Kirsty Scott, The Guardian, Friday June 18, 2004.

Anthony Giddens, Sociology (Polity, 2006), chapter 21, “Cities and Urban Spaces”.

Friday 06/11/09: The iPod and the City

Modern devices like personal stereos, iPods, mobile phones and laptops are increasingly common features of our urban landscapes and soundscapes. They are the means through which information, entertainment and knowledge are encoded and accelerated through increasingly mobile urban worlds. But if such devices are characterised by privatised acts of consumption what are the implications for the city and urban relations? Do iPods reinforce the blasé attitude, severing the urbanite from their environment or do city dwellers re-enchant their relations to the city through music? How best can we make sense of the rhythms, routines and narratives of city life when conjoined to a personalised urban soundtrack? And what are the implications for how we connect or disconnect from one another?

Readings:

[WEBCT] Michael Bull, "Sounding Out Cosmopolitanism", chapter 3 of Sound Moves: iPod Culture and the Urban Experience, London: Routledge, 2007: pp. 24-37.

Michael Bull, 2000, “Filmic Cities and Aesthetic Experience”, chapter 7 of Sounding Out the City: Personal Stereos and the Management of Everyday Life, Oxford: Berg, pp. 85-96.

Dylan Jones, 2005, “Journey to the Centre of the iPod”, chapter 19 of iPod Therefore I Am: A Personal Journey Through Music, London: Phoenix.

Tia DeNora, “Music and the Body”, chapter 4 of Music in Everyday Life, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 75-108.

Michael Bull, 2005, “No Dead Air! The iPod and the Culture of Mobile Listening”, Leisure Studies, vol. 24, no. 4, October 2005: pp. 343-355.

Sophie Arkette, 2004, “Sounds Like City”, Theory, Culture and Society, vol. 21, no. 1: pp. 159-168.

Nick Prior, 2008, “OK Computer: Mobility, Software and the Laptop Musician”, Information, Communication and Society, 11: 7, October 2008: pp912-932.

Steven Levy, 2007, The Perfect Thing: How the iPod Shuffles Commerce, Culture and Coolness, London: Simon and Schuster.

Jean-Paul Thibaud, 2003, “The Sonic Composition of the City”, chapter 18 of The Auditory Culture Reader, Michael Bull and Les Back (eds), Oxford: Berg, pp. 329- 342.

Leander Kahney, 2005, The Cult of iPod, San Francisco: No Starch Press, especially chapter 2, “New Listening Habits”.

21 Steven Johnson, 1997, Interface Culture: How New Technology Transforms the Way We Create and Communicate, New York: Basic Books.

WEEK 8

Tuesday 10/10/09: The Virtual City

The final session will argue that the rise of the internet and associated technologies has opened up a series of questions regarding “real” and “virtual” space. It will examine the provocative assertion that cities as we know them are being “dematerialised” as more and more people go on-line and interact in virtual spaces and join “virtual communities”. How might the “virtual city” be transforming the way identity, the body and the self are constituted in society?

Readings:

[WEBCT] Keith Hampton, "Netville: Community On and Offline in a Wired Suburb", in The Cybercities Reader, edited by Stephen Graham (Routledge: London, 2004), pp. 256-261.

[WEBCT] William J. Mitchell, City of Bits: Space, Place and the Infobahn, (MIT Press, 1996), chapter 2.

Michael Ostwald, “Virtual Urban Futures”, chapter 43 of The Cybercultures Reader, David Bell, Barbara M. Kennedy (eds) (Roultedge, 2000).

David Beer, “Tune out: Music, Soundscapes and the Urban Mise-en-Scène”, Information, Communication & Society, vol. 10, no. 6 (special issue on Urban Informatics), pp. 846-866, 2007.

William J. Mitchell, Me + +: The Cyborg Self and the Networked City (MIT Press, 2003).

William J. Mitchell, “Soft Cities”, in The City Cultures Reader, Malcolm Miles, Tim Hall and Iain Borden (eds) (Routledge, 2000).

Alessandro Aurigi and Stephen Graham, “Cyberspace and the City: The ‘Virtual City’ in Europe”, in A Companion to the City, Gary Bridge and Sophie Watson (eds) (Blackwell, 2003).

Michael Dear, “From Sidewalk to Cyberspace (and back to Earth again)”, chapter 11 of The Postmodern Urban Condition (Blackwell, 2000).

Julian Dibbell, “A Rape in Cyberspace (or, Tinysex, and how to make one)”, chapter 1 of My Tiny Life, also available at: http://www.juliandibbell.com/texts/bungle.html

22 Graham McBeath and Stephen Webb, “Cities, Subjectivity and Cyberspace”, chapter 14 of Imagining Cities: Scripts, Signs, Memory, Sallie Westwood and John Williams (eds) (Routledge, 1995).

The Cybercities Reader, edited by Stephen Graham (Routledge, 2004).

Paul Virilio, Open Sky, (Verso, 1997).

Manuel Castells, The Informational City (Blackwell, 1989), chapter 3.

William J. Mitchell, E-Topia: Urban Life, Jim – but not as we know it”, (MIT Press, 1999).

Howard Rheingold was one of the pioneers of the notion of ‘virtual communities’ and his site contains information about various aspects of life on the internet. www.rheingold.com

UNIT 4: Social Change and Evolution (Weeks 8 – 10): Jonathan Hearn Overview: If Unit 1 was about how social order emerges out of human interaction, this unit is about how that social order changes, often profoundly, over time. Other units have already opened up some of these issues, e.g. how social norms in regard to gender, the body and sexuality have been changing in recent decades, and processes of urbanisation. ‘Change’ is the norm in the modern world, and in a sense, sociologists always study social change—e.g. how family forms, gender roles, class structures, nation-states, financial markets, among other things, are being transformed by a restless world. The term ‘social change’ however, is usually associated not just with any kind of change (e.g. fashions in hair styles, short–term business cycles), but with major events and shifts that seem to alter the course of human history. More specifically, it often designates fundamental changes at the institutional level, such that a whole societal pattern undergoes a shift. For instance, the rise of modernity is often thought of as a fundamental shift from a system of social relations based on agricultural production with caste-like social statuses, to one based on industrial production in which stratification is generated by the dynamics of markets. In this unit we will explore various attempts to explain and understand recurring patterns and processes in the history of human societies.

After an introductory overview lecture, we will critically explore four, often overlapping, ways of thinking about how social change works: 1. The idea that human society tends to move, almost inevitably, from more simple to more complex forms of organisation. 2. The idea that change (improvement? advance?) in technology is the main driver of social changes more generally, especially over the last few centuries. 3. The idea that social conflict and competition between groups is fundamental, and the main stimulus to social change. 4. The idea that social institutions may sometimes impede social change, and that this might help explain the variable trajectories of social change around the world.

23 Your task for this unit is to master these ideas, consider their strengths and weaknesses as modes of explanation, and think as widely as you can about how these ideas might be applied to the social world you know.

Electronic Resources: many of the articles in these readings are available as electronic resources through the Edinburgh Library catalogue. This is indicated by: ElecRes

Friday 13/11/09: Social change and the ‘long view’

The first step with this subject is to get a picture in our minds of the overall trajectory of human history, so that our society, and how it is changing, can be situated within a wider history of societies and how they evolve. This lecture sets the stage by examining the definitions and basic dimensions of social change, and the general ‘image’ we have of human history.

Readings:

NB: Multiple copies of each of the first three of these texts will be on reserve in the Main Library. You may want to read further in them in regard to subsequent lectures.

Nolan, Patrick and Lenski, Gerhard (2004), ‘Types of Human Societies’, in Human Societies: An Introduction to Macrosociology, 10th edn, Paradigm Publishers, pp. 62- 73.

Sztompka, Piotr (1993), from chapter one: ‘Fundamental concepts in the study of change’, in The Sociology of Social Change, Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 3-7.

Noble, Trevor (2000), ‘Introduction: Dimensions of the Debate’, in Social Theory and Social Change, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1-16.

Chirot, Daniel (1994), How Societies Change, London: Pine Forge Press. (A short, accessible narrative of human history, from a Parsonian-Functionalist perspective. Skim if you can).

Hearn, Jonathan (2006), excerpts from Rethinking Nationalism: A Critical Introduction, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 61-65, 104-108.

WEEK 9

Tuesday 17/11/09: From Simple to Complex

One of the most basic and recurring sociological ideas is that society has tended to evolve from simpler to more complex forms. We explore the concepts of ‘the division of labour’ and ‘differentiation’ that have been used to articulate this idea, and consider whether current discussions of ‘globalisation’ support this thesis once again.

Readings:

24 Aron, Raymond (1970), ‘I. De la division du travail social’, in Main Current in Sociological Thought, Vol. 2, New York: Doubleday Books, pp. 11-24.

ElecRes Bellah, Robert (1964), ‘Religious Evolution’, American Sociological Review 29(3): 358-374. [Reprinted in S. N. Eisenstadt (ed.) (1970).

Held, David, et al. (2000), ‘Rethinking Globalisation’, in D. Held and A. McGrew (eds), The Global Transformations Reader, Cambridge: Polity, pp. 54-59.

Giddens, Anthony (2000), ‘The Globalising of Modernity’ in D. Held and A. McGrew (eds). Op cit.. pp. 92-98.

Further Readings:

Spencer, Herbert (1996 [1860]), ‘The Social Organism’ in R. J. McGee and R. L. Warms (eds), Anthropological Theory: An Introductory History, London: Mayfield, pp. 10-26.

ElecRes Eisenstadt, S. N. (1964), ‘Social Change, Differentiation and Evolution’, American Sociological Review 29(3): 375-386.

Wenke, Robert (1990), ‘The Evolution of Complex Societies’, Patterns in Prehistory, 5th edn, Oxford UP, pp. 279-323.

Friday 20/11/09: The March of ‘Technology’

Often what we find most striking in the study of social change is the impact of technology, living as we do in a world of rapid technological change. This raises various questions we will explore: What is ‘technology’? What is its relationship to problem-solving and innovation more generally? How do changes in technology impact the organisation of society, and vice-versa? We also look briefly at the underlying issue of the harnessing and utilisation of energy.

Readings:

ElecRes Rosa, Eugene A., et al. (1988), ‘Energy and Society’, Annual Review of Sociology 14: 149-72. Read pp. 149-155 (the rest is optional).

Lenski, Gerhard and Patrick Nolan (2004), ‘The Industrial Revolution’, in Human Societies: An Introduction to Macrosociology, 10th edn, Paradigm Publishers, see pp. 187-112. Mann, Michael (1986), ‘The rise of the European pike phalanx’, in The Sources of Social Power, Vol. I, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 18-20.

Further Readings:

Various Authors (2000), ‘Part C2, The Global Impact of New Technologies’, in J. Beynon and D. Dunkerley (eds), Globalisation: The Reader, London: The Athalone Press, pp. 205-230.

25 Anderson, Benedict (1994), ‘Imagined Communities’, in J. Hutchinson and A. D. Smith (eds), Nationalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

ElecRes Thompson, E. P. (1967), ‘Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism’, Past & Present, Vol. 38: 56-97. [Also in Hall and Bryant 2005]

Browse the entry on Marx at the ‘Dead Sociologists Index’: http://media.pfeiffer.edu/lridener/DSS/#marx

WEEK 10

Tuesday 24/11/09: Conflict and Competition

Explanations of social change frequently centre on the dynamics of conflict and competition in social relations (and cognate concepts such as antagonism, rivalry, contestation, etc.). We examine two major ways of thinking about this—called ‘marxian’ and ‘liberal’ for convenience—and the idea of ‘class conflict’ as a motor of social change. The development of the welfare state, and the irruption of revolutions are considered as prime examples of conflict/competition driven social change.

Readings:

Bendix, R. and S. M. Lipset (1953), ‘Karl Marx’ Theory of Social Classs’, in R. Bendix and S. M. Lipset (eds), Class, Status and Power: A Reader in Social Stratification, New York: Free Press, pp. 26-34.

Marshall, T. H. (1953). ‘The Nature of Class Conflict’, in R. Bendix and S. M. Lipset (eds), op cit., pp. 81-87.

Pierson, Christopher (1991), ‘Capitalism, Social Democracy and the Welfare State I: Industrialism, Modernization and Social Democracy’, in Beyond the Welfare State?, University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University, pp. 6-39.

Sztompka, Piotr (1993), ‘Revolutions: The Peak of Social Change’, in The Sociology of Social Change, Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 301-321.

Further Readings:

Burke, Peter (2005) ‘Social Theory and Social Change’, in History and Social Theory, 2nd edn., Cambridge: Polity, pp. 141-171. Coser, Lewis A. (1956), The Functions of Social Conflict, London: Routledge and Keegan Paul.

ElecRes Coser, Lewis A. (1957) ‘Social Conflict and the Theory of Social Change’ British Journal of Sociology 8(3): 197-207.

Collins, Randall (1975), Conflict Sociology: Toward an Explanatory Social Science, NewYork: Academic Press.

26 Dobbin, Frank (2001), ‘Why the Economy Reflects the Polity: Early Rail Policy in Britain, France, and the United States’, in M. Granovetter and R. Swedberg (eds), The Sociology of Economic Life, Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

ElecRes Fligstein, Neil (1996), ‘Markets as Politics: A Political-Cultural Approach to Market Institutions’, American Sociological Review 61(4): 656-673.

Haugaard, Mark (2002), ’15 Haugaard’ (excerpt from The Constitution of Society), in M. Haugaard (ed.), Power: A Reader, Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 304-328.

Malia, Martin (2006), History’s Locomotives: Revolutions and the Making of the Modern World, New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Marwick, Arthur (1974), War and Social Change in the Twentieth Century, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

ElecRes Stern, Charlotta (1999), ‘The Evolution of Social-Movement Organizations: Niche Competition in Social Space’ European Sociological Review 15(1): 91-105.

Wrong, Dennis H. (1994), ‘Group Conflict, Order, and Disorder’, in The Problem of Order: What Unites and Divides Society, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univeristy Press, pp. 202-243.

Friday 29/11/09: Impediments to Change (and the ‘Rise of the West’?)

We conclude by looking at the other side of the coin, how social development and change can be inhibited or channelled by ideological and institutional factors. This question figures in major debates about the causes of ‘the rise of capitalism and the West’ in relationship to the rest of the world.

Readings:

David, Paul A. (1985), ‘Clio and the Economics of QWERTY’, The American Economics Review 75(2): 332-337. [Also in Hall and Bryant 2005]

ElecRes White, Lynn, Jr. (1967), ‘The Historical Roots of our Ecological Crisis’, Science, new series 155(3767): 1203-1207. [Also in Hall and Bryant 2005]

Hall, John A. (1985), ‘Capstones and Organisms: Political Forms and the Triumph of Capitalism’, Sociology 19(2): 173-192.

Goody, Jack (2004) ‘Introduction: The Notion of Capitalism and the Rewriting of World History’, in Capitalism and Modernity: The Great Debate, Cambridge: Polity, pp. 1-18

Further Readings:

Chirot, Daniel (1994), ‘Toward a Theory of Social Change’, in How Societies Change, London: Pine Forge Press, pp. 117-131.

27 Hall, John A. (1985), ‘Patterns of History’ in Power and Liberties: The Causes and Consequences of the Rise of the West, Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, pp. 3-23.

Mahoney, James (2000), “Path Dependence in Historical Sociology,” Theory and Society 29(4): 507-548.

Lecture Notes ‘Path dependence’ (institutional constraints) Ideational (religious) constraints (White, Weber) ‘Capstone states’ (Hall) Why did the ‘West’, ‘rise’? (Goody)

Further General Readings for the Unit as a Whole: If you have a strong interest in this topic, here are various general studies of, and edited volumes about social change and social theory, that you might consult. This includes the books cited for the first lecture, which are probably the best places to start reading further. All these books are held by the Main Library. They are in reverse chronological order. Those from 1970 and before reflect the strong Parsonian functionalist paradigm in sociology of that time. Those from the 1980s on reflect the more diverse array of approaches one finds today.

Hall, John A. and Bryant, Joseph M. (eds) (2005), Historical Methods in the Social Sciences, 4 volumes, London: Sage. [A valuable resource with many key articles republished in it.]

Burke, Peter (2005), History and Social Theory, 2nd edn., Cambridge: Polity.

Nolan, Patrick and Lenski, Gerhard (2004), Human Societies: An Introduction to Macrosociology, 10th edn, Paradigm Publishers.

Noble, Trevor (2000), Social Theory and Social Change, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Chirot, Daniel (1994), How Societies Change, London: Pine Forge Press.

Sztompka, Piotr (1993), The Sociology of Social Change, Oxford: Blackwell.

Vago, Steven (1989), Social Change, 2nd edn., Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Gellner, Ernest (1988), Plough, Sword and Book: the Structure of Human History, London: Paladin.

Hall, John A. (1985), Power and Liberties: The Causes and Consequences of the Rise of the West, Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

Tilly, Charles (1984), Big Structures, Large Processes, Huge Comparisons, Russell Sage Foundation.

28 Wolf, Eric R. (1982), Europe and the People Without History, Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

Parsons, Talcott (1977), The Evolution of Societies, Englewood, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Editor Jackson Toby provides a helpful introduction to Parsons’ ideas in Ch. 1.]

Eisenstadt, S. N. (ed.) (1970), Readings in Social Evolution and Development, Oxford: Pergamon Press.

ElecRes American Sociological Review 29(3) (1964). [Special issue on social change theories as influenced by Talcott Parsons]

Etzioni, A and E. Etzioni (eds) (1964), Social Change: Sources, Patterns and Consequences, New York and London: Basic Books.

Zollschan, G. K. and W. Hirsch (eds), (1964), Explorations in Social Change. Routledge and Keegan Paul.

WEEK 11

No lectures - Revision

Tutorial Topics

TUTORIAL TOPICS FOR UNIT 1 NO SUCH THING AS SOCIETY

WEEK 1 – NO TUTORIALS

WEEK 2

Come ready to discuss the results of the experiment performed in the lecture on Tuesday of week 1, how you played the ‘ultimatum’ game on Friday of week 1, and what you answered when faced with the two versions of the Wason selection task. We’ll also play and discuss a further game (a ‘public goods’ game, investigating what social scientists call ‘collective action’) in this tutorial. This game is described in *Scott Barrett, Environment and Statecraft: The Strategy of Environmental Treaty-Making (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), pp. 3-5, but please don’t read this until after the tutorial.

WEEK 3

‘Why can’t a woman be more like a man?’ sang Henry Higgins in My Fair Lady. Read as much as you can of Norah Vincent, Self-Made Man: My Year Disguised as a Man (London: Atlantic, 2006), which describes an informal experiment addressing Higgins’s question, in which she attempted, with some success, to pass as a man. *Pp. 20-61 of Self-Made Man are available on

29 WebCT (the ‘Ned’ referred to in the chapter is the ‘man’ Vincent was enacting).

Studying what a woman has to do to pass as a man (or vice versa) is interesting because it throws light on what men have to do to pass as men, or women to pass as women: see pp. *180-181 of Garfinkel, Studies in Ethnomethodology (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1967). If you want, dip into the remainder of Garfinkel’s account of ‘Agnes’ (pp. 116-185), although it’s much harder going than Vincent. ‘Agnes’ was a biologically intersexed person, brought up as a male, who was seeking to pass as a woman.

Now imagine that you were able to disguise yourself so that you could pass ‘physically’ as a member of the opposite sex (as Vincent did). What would be involved in behaving as a man or woman? What does this reveal about: a) roles, b) norms, and c) the presentation of self? (Have you, e.g., come across instances of ‘tact’, in Goffman’s sense of an audience saving a failed self-presentation, for instance by tacitly ignoring a failure?)

Do you agree that women and men are, in Garfinkel’s words, ‘cultural events that members [of society] make happen’ (p. 181)?

WEEK 4

Essay writing skills: this tutorial will review key issues that need to be considered when writing a University-level essay: planning, relevance, substance, argument, presentation and referencing

TUTORIAL TOPICS FOR UNIT 2 SEX DRUGS AND ROCK AND ROLL: HAVE WE NEVER HAD IT SO GOOD?

WEEK 5: Clothes and individualism

Try to wear at least one of your favourite articles of clothing to the tutorial and come ready to explain (briefly) why you like it and where you bought it. Use the readings for Lecture 1 to discover, as a group, whether you can fit the various items chosen by tutorial members into the categories put forward in the lectures.

WEEK 6: Drink and drugs

Read the executive summary in McCormick et al (2007). Bearing in mind the evidence presented in Sheehan and Ridge (2001), Levine (1978) and the unit lectures, identify at least ten criticisms of the arguments and evidence advanced in the McCormick et al report. You may also find it useful to draw both upon your own experiences of drinking and the evidence from the class survey.

30 TUTORIAL TOPICS FOR UNIT 3 THE CITY

WEEK 7

Reflect on your experience of the city: can you think of any examples of the blasé attitude, urban indifference and apathy that might reinforce the conclusions of Simmel or the Chicago School? Is there a difference between social relations in the country and the city? List them. Find out as much as you can about the Kitty Genovese case. Do you think it is a straightforward example of the decline of community and reflective of the ills of contemporary urban life or are their other explanations? Can you think of more contemporary examples or even counter-examples?

Readings:

Simmel [WebCT], Wirth [WebCT], Gado WEEK 8

Think about how, when and where you listen to your MP3 player. Does it change the way you relate to other people? Does it make you see the city differently? How does it structure your moods and rhythms, your thoughts and emotions in transit, your routines and habits? Do you think the internet and email is changing the way we interact? If so, does this herald the end of the city as we know it? Speculate on different futures for the city: will cities of the future be more or less global, virtual, dynamic, public, polluted, exciting, disordered?

Readings:

Bull [WebCT], Hampton [WebCT]

TUTORIAL TOPICS FOR UNIT 4 SOCIAL CHANGE AND EVOLUTION

WEEK 9

First, imagine you are a team of sociologist in the year 2109, looking back at the momentous social changes of the last 100 years. What do you imagine those are? How has society changed? Next, ask yourselves what assumptions you made about the main causes of social change, that led you to imagine the future in this way? Has your group come up with competing, alternative versions of society in 2109? Discuss these differences and their reasons.

WEEK 10

Consider the readings from the lecture on ‘conflict and competition’. It is often argued that the core dynamic of social conflict that characterised

31 industrial society was that between ‘working’ and ‘capitalist’ classes. But with the decline of the industrial sector, and the growth of the welfare state and the middle class, that axis conflict has weakened. What dynamics of social conflict might be of increasing importance today, and likely to affect future social change? Between: Genders? Generations? Religions? Ethnicities? (Any others?). Or, might we expect renewed conflict along economic/class lines? Try to justify your speculations.

Readings you might want to refer to:

Nolan, Patrick and Lenski, Gerhard (2004), ‘The Evolution of Human Societies’ (ch 4, pp. 44-61), in Human Societies: An Introduction to Macrosociology, 10th edn, Paradigm Publishers. Burke, Peter (2005) ‘Social Theory and Social Change’, in History and Social Theory, 2nd edn., Cambridge: Polity, 141-171

Essay Topics

Essay is due 3pm, Friday 6th November 2009 (Week 7)

Your essays must be no more than 1500 words.

1. Social order requires social behaviour to be predictable and individuals to cooperate. Amongst the explanations of social order are five outlined by Hector and Horne: (shared) ‘meaning’, ‘values and norms’, ‘power and authority’, ‘spontaneous interaction’ and ‘networks and groups’. Describe how at least three of these (or other) factors might explain social order, and discuss the extent to which you find the explanations convincing.

Readings:

The main reading is Michael Hechter and Christine Horne, Theories of Social Order: A Reader (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003): the quote in the question is on p. 27. Don’t restrict yourself to their introductions: also use in your essay some of the extracts they reprint from other authors, as well as any other readings from Unit 1 that seem to you to be helpful.

2. ‘The self is not a thing, nor is it equivalent to the body, nor is it mysteriously located somewhere inside the person. Rather…the self is something named, to which attention is paid and towards which actions are directed’ (Hewitt, Self and Society, p. 76). Explain what is meant by this claim, and illustrate its meaning with examples taken from Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life or elsewhere (including, if you wish, your own personal experience).

Readings:

[WEBCT] Charles Horton Cooley, Human Nature and the Social Order, which is the

32 second, separately-paginated section of Cooley, Two Major Works (Glencoe, IL: Free Press, 1956), pp. 183-185. The relevant passage, Cooley’s ‘The Looking-Glass Self’, is also available at http://www2.pfeiffer.edu/~lridener/DSS/Cooley/LKGLSSLF.HTML

[WEBCT] George Herbert Mead, Mind, Self, and Society from the Standpoint of a Social Behaviorist (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1934), pp. 135-178. Part of this section of Mead’s book is also to be found in Michael Hechter and Christine Horne, Theories of Social Order: A Reader (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003), pp. 65-72.

John P. Hewitt, Self and Society: A Symbolic Interactionist Social Psychology (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2007).

[WEBCT] Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (Edinburgh: Social Sciences Research Centre, 1956; later editions published by Penguin and others). As noted, it’s somewhat preferable to use one of the published editions, which are rather more explicit on some key points than the original report.

3. ‘Fashion allows one both to follow others and to mark oneself off from them...’ (Craib, 1997: 170). Outline Simmel’s account of the contradictory nature of fashion and explain why fashion is such an important feature of modern societies.

Georg Simmel ([1904] 1957). ‘Fashion’ American Journal of Sociology, 62, 541-548. Diana Crane (2000) ‘The Social Meanings of Hats and T-shirts’ from Fashion and Its Social Agendas: Class, Gender, and Identity in Clothing Univ of Chicago Press. Available at http://www.press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/117987.html

William H Sewell (1992) ‘A Theory of Structure’ in Am. Jrnl. Sociology 98(1)1-29.

Angela McRobbie 1994 ‘Second hand dresses and the role of the ragmarket’ in Postmodernism and Popular Culture. Routledge.

Elizabeth Wilson 1985 Adorned in Dreams Virago.

Anthony Giddens 1991 Modernity and Self Identity Ch 6 ‘The tribulations of the self’. Cambridge: Polity.

‘Pecs and penises the meaning of girlie culture’ Ch 9 pp. 122-131. of Angela McRobbie In the culture society Routledge 1999

4. Discuss whether young people are rebelling or conforming when they ‘binge’ drink or take ‘recreational’ drugs?

Harry G. Levine (1978) ‘The Discovery of Addiction: Changing conceptions of habitual Drunkeness in America’ Journal of Studies on Alcohol 15 493-506.

33 Sheehan, Margaret and Ridge, Damien (2001) ‘“You Become Really Close…You Talk About The Silly Things You Did, And We Laugh”: The Role Of Binge Drinking In Female Secondary Students' Lives’, Substance Use & Misuse 36(3) 347 — 372.

Amanda V. McCormick, Irwin M. Cohen, Raymond R. Corrado, Lindsay Clement, & Colleen Rice (2007) ‘Binge Drinking among Post-Secondary Students in British Columbia’ BC Centre for Social Responsibility.

Fiona Measham and Kevin Brain 2005 ‘‘Binge’ drinking, British alcohol policy and the new culture of intoxication’ in Crime Media Culture Vol 1. pp. 262-83. and at http://cmc.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/1/3/262

Fiona Measham 2004 ‘The decline of ecstasy, the rise of ‘binge’ drinking and the persistence of pleasure’ in Probation Journal Vol 51; pp.309-326. and at http://prb.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/51/4/309

Kevin Brain, Howard Parker and Tom Carnwath,(2000) 'Drinking with Design: young drinkers as psychoactive consumers', Drugs: education, prevention and policy, 7:1, 5 — 20.

Drug misuse declared: Findings from the 2003-04 British Crime Survey available at http://www.crimereduction.homeoffice.gov.uk/drugsalcohol/drugsalcohol86.htm (This is a summary of findings. You can also access the full report there.)

Elizabeth Fuller (ed) 2005 Smoking, drinking and drug use among young people in England 2004. ONS/Nat Centre for Social Research. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/document s/digitalasset/dh_4118154.pdf.

Hadfield, Phil (2006) Bar Wars: Contesting the Night in Contemporary British Cities, Oxford University Press,

Hobbs, D., S. Lister, P. Hadfield, S. Winlow and S. Hall (2000) ‘Receiving Shadows: Governance and Liminality in the Night-time Economy’, British Journal of Sociology 51(4): 701–18.

Anthony Giddens 1991 Modernity and Self Identity Ch 6 ‘The tribulations of the self’. Cambridge: Polity.

34 Appendix One: A Guide to Referencing

The fundamental purpose of proper referencing is to provide the reader with a clear idea of where you obtained your information, quote, idea, etc. In Sociology we insist on the Harvard system of referencing. The following instructions explain how it works. 1. After you have quoted from or referred to a particular text in your essay, add in parentheses the author’s name, the publication date and page numbers (if relevant). Place the full reference in your bibliography. Here is an example of a quoted passage and its proper citation: Quotation in essay: ‘Societies are much messier than our theories of them. In their more candid moments, systematizers such as Marx and Durkheim admitted this; whereas the greatest sociologist, Weber, devised a methodology (of “ideal-types”) to cope with messiness’ (Mann, 1986: 4). Book entry in bibliography: Mann, M. 1986. The Sources of Social Power, Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Note the sequence: author, year of publication, title, edition or translation information if needed, place of publication, publisher. 2. If you are employing someone else’s arguments, ideas or categorization, you will need to cite them even if you are not using a direct quote. One simple way to do so is as follows: Mann (1986: 32) argues that contemporary issues are best understood through historical comparison.

35 3. Your sources may well include journal or newspaper articles, book chapters, and internet sites. Below we show you how to cite these various sources. (i) Chapters in book: In your essay, cite the author, e.g. (Jameson, 1999). In your bibliography details should be arranged in this sequence: author of chapter, year of publication, chapter title, editor(s) of book, title of book, place of publication, publisher, article or chapter pages. For example: Jameson, F. 1999. ‘The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism.’ A. Elliott. (ed.). The Blackwell Reader in Contemporary Social Theory. Oxford: Blackwell: 338-50.

(ii) Journal article: In your essay, cite the author, e.g. (Gruffydd-Jones, 2001). In your bibliography, details should be arranged in this sequence: author of journal article, year of publication, article title, journal title, journal volume, journal issue or number, article pages. For example: Gruffydd-Jones, B. 2001. ‘Explaining Global Poverty: A Realist Critique of the Orthodox Approach.’ Journal of Critical Realism, 3 (2): 2-10.

(iii) Newspaper or magazine article: If the article has an author, cite as normal in the text (Giddens, 1998). In bibliography cite as follows: Giddens, A. 1998. ‘Beyond left and right.’ The Observer, 13 Sept: 27-8. If the article has no author, cite name of newspaper in text (The Herald) and list the source in the bibliography by magazine or newspaper title. For example: The Herald. 1999. ‘Brown takes on the jobless’, 6 Sept: 14.