Environmental Law – Fall 2007 – Prof. Nash

POLICY

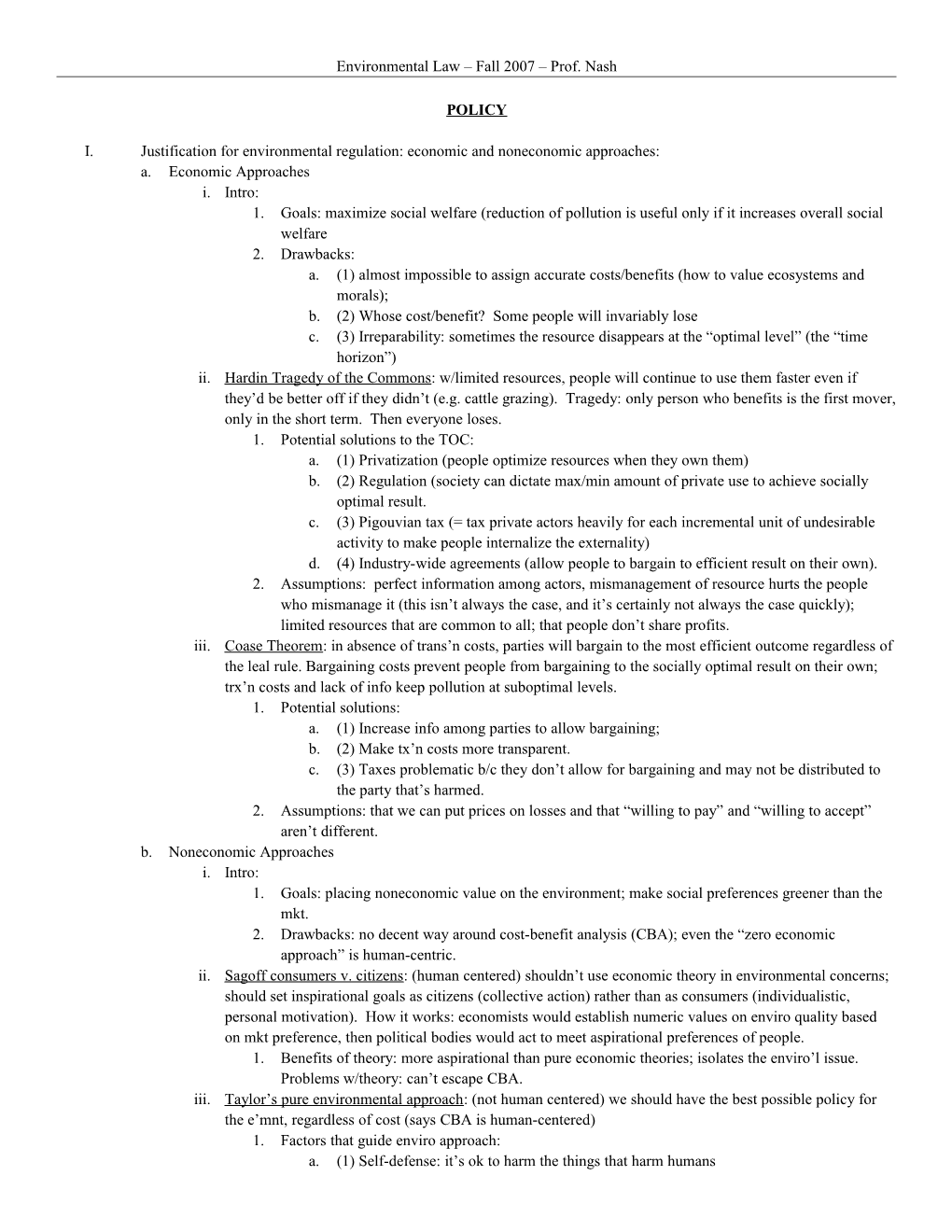

I. Justification for environmental regulation: economic and noneconomic approaches: a. Economic Approaches i. Intro: 1. Goals: maximize social welfare (reduction of pollution is useful only if it increases overall social welfare 2. Drawbacks: a. (1) almost impossible to assign accurate costs/benefits (how to value ecosystems and morals); b. (2) Whose cost/benefit? Some people will invariably lose c. (3) Irreparability: sometimes the resource disappears at the “optimal level” (the “time horizon”) ii. Hardin Tragedy of the Commons: w/limited resources, people will continue to use them faster even if they’d be better off if they didn’t (e.g. cattle grazing). Tragedy: only person who benefits is the first mover, only in the short term. Then everyone loses. 1. Potential solutions to the TOC: a. (1) Privatization (people optimize resources when they own them) b. (2) Regulation (society can dictate max/min amount of private use to achieve socially optimal result. c. (3) Pigouvian tax (= tax private actors heavily for each incremental unit of undesirable activity to make people internalize the externality) d. (4) Industry-wide agreements (allow people to bargain to efficient result on their own). 2. Assumptions: perfect information among actors, mismanagement of resource hurts the people who mismanage it (this isn’t always the case, and it’s certainly not always the case quickly); limited resources that are common to all; that people don’t share profits. iii. Coase Theorem: in absence of trans’n costs, parties will bargain to the most efficient outcome regardless of the leal rule. Bargaining costs prevent people from bargaining to the socially optimal result on their own; trx’n costs and lack of info keep pollution at suboptimal levels. 1. Potential solutions: a. (1) Increase info among parties to allow bargaining; b. (2) Make tx’n costs more transparent. c. (3) Taxes problematic b/c they don’t allow for bargaining and may not be distributed to the party that’s harmed. 2. Assumptions: that we can put prices on losses and that “willing to pay” and “willing to accept” aren’t different. b. Noneconomic Approaches i. Intro: 1. Goals: placing noneconomic value on the environment; make social preferences greener than the mkt. 2. Drawbacks: no decent way around cost-benefit analysis (CBA); even the “zero economic approach” is human-centric. ii. Sagoff consumers v. citizens: (human centered) shouldn’t use economic theory in environmental concerns; should set inspirational goals as citizens (collective action) rather than as consumers (individualistic, personal motivation). How it works: economists would establish numeric values on enviro quality based on mkt preference, then political bodies would act to meet aspirational preferences of people. 1. Benefits of theory: more aspirational than pure economic theories; isolates the enviro’l issue. Problems w/theory: can’t escape CBA. iii. Taylor’s pure environmental approach: (not human centered) we should have the best possible policy for the e’mnt, regardless of cost (says CBA is human-centered) 1. Factors that guide enviro approach: a. (1) Self-defense: it’s ok to harm the things that harm humans b. (2) Proportionality: non-basic human interests can’t override basic interests of other organisms c. (3) Min wrong: non-basic interests of humans threaten the environment, but they’re essential and can’t be stopped d. (4) Distributional justice: where an act can harm humans and nature, it has to be distributed equally. e. (5) Restitutive wrong: make up for (3) and (4) with other acts. 2. Benefits: helps us realize that CBA is human-centered. Drawbacks: still is human centered, no way to get to zero environmental costs. II. Federalism a. Limits on fed’l ctrl: i. Commerce Clause: fed’l govn’t allowed to regulate interstate commerce; this is where a lot of environmental regulation comes from (b/c of “effect” on interstate commerce). 1. Examples: a. Navigable waterways in the CWA: i. Bayview Homes: Ct held that “navigable” is ltd importance b/c comm. cl power is broad; ct determined that “navigable waters” incl waters adjacent and connected to waters a boat can pass through, in order to regulate dredge dumping. ii. SWANCC: Ct went w/const’l avoidance re: authority to regulate a pond unconnected to any “navigable” waterway. Didn’t use comm. cl to invalidate. iii. Rapanos: Ct limited the Army Corps’s authority to issue “migratory bird” rule; holding (that has been followed subsequently) was that a hydrological connection to a navigable waterway must exist for fed’l govn’t to be able to regulate a body of water. Ct said that fed’l govn’t has jx over navigable waters in the US, Congress must be explicit when it gets to the edge of commerce clause authority. b. Mass v. EPA: Ct held that the EPA must regulate carbon emissions from mobile sources (b/c of interstate effect?) 2. Intersecting authority: const’l authority, statutory authority, regulatory authority. Congress must be clear when it gets to the edge of its Commerce Clause authority (Rapanos) ii. Supremacy Clause: fed’l law is supreme, state law must give way when a fed’l law competes. 1. Examples: a. Pataki (see below) b. Mobile sources expressly preempt any and all state regulations (except EPA waives stricter California standard). iii. Cooperative federalism: States can control fed’l govn’t by proposing regulations that the EPA ratifies. 1. Examples: a. NRDC v. EPA: state WQs can become fed’l law once approved. b. Arkansas v. Oklahoma: one state wanted to stop the other from polluting into a river running into it, cooperative fed’lism’s flaws showed. Ct held that the EPA may (not must) consider downstream discharge that will affect other state’s water in violation of WQs. b. Two possible approaches to fed’l control: i. (1) National Standards: uniform pollution ctrl across board; but doesn’t allow for variances to do better. ii. (2) Federal Floor: minimum pollution standard that’s not fixed; this allows states to go beyond what the fed’l govn’t requires. c. Fed’l ctrl vs. State ctrl: i. Pro-Fed’l Ctrl 1. State race to the bottom (to make less stringent environmental standards and attract industry); assumes that there’s no spillover, and that lower pollution control is more desirable to companies. a. Counter: Revesz says that models don’t show there to be a race to the bottom here; challenges assumptions of spillover. 2. Collective action (Stewart) centralized control lowers trx’n costs in environmental lobbying b/c a centralized govn’t allows diffuse groups to rally together for a common cause, and environmental lobbying is more effective at the nat’l level. 3. Potential benefits: a. Uniform standards –> cheaper production b. Only w/fed’l govn’t ctrl can we have cap-and-trade systems (e.g. SO2 trading contingent on states not interfering). i. Illinois SO2 case: Ct said that IL couldn’t limit coal plants’ ability to buy lower SO2 content coal from the west. ii. Pataki: Ct held that NY couldn’t limit downstream trading of (fed’l) SO2 permits. ii. Anti-Fed’l Ctrl: 1. Race to the top? W/o fed’l control, some states may have a higher standard on their own. 2. Sub-optimally high pollution control: states may be better served w/more pollution than the fed’l govn’t allows (failure to account for local preferences) 3. States as laboratories: lack of fed’l control is the best chance for a good solution 4. Distribution and population densities: nat’l standards don’t incorporate realities on the ground. a. Union Electric (CAA): industry challenged EPA approval of a CAA SIP w/ no consideration of costs. Ct ehld that the act delegates consideration of costs to states and EPA isn’t empowered to consider costs. III. Distributional Consequences and Allocating Pollution: a. Approaches to regulating pollution and their distributional consequences: i. (1) Command & control (cap pollution, give actors no choice on how to pollute); 1. E.g. total bans, caps on individual plants, BAT limits, effluent-based limits. 2. Remedy for violation: D must clean up. 3. Good b/c can take distributional factors into account, govn’t running of the programs creates some independence, but bad b/c it may result in socially suboptimal pollution levels. ii. (2) Market-based mechanisms: place a total cap on pollution, but allow for tradable permits for most efficient allocation. 1. E.g. tradeable permits, taxes a. Pigouvian taxes: no caps, seen often in Europe but not the US. Bad b/c if rate is set wrong, there’s little effect. Taxes must keep up w/market (inflation) to work; constant reevaluation. Good b/c govn’t gets the money directly. b. Permits: there must be a cap; can also allow only certain kinds of trading. 2. Remedy for violation: compensate or clean up in other ways. 3. Good b/c allows for most efficient allocation of resources; companies have incentives to pollute less or trade surplus to others; forces fed’l govn’t to carefully monitor and ensure that people are complying and incentives are working. b. Fairness and Distribution i. What’s fair? Burden entire population equally? Burden proportionate to production? Shift burden to those who lack environmental quality or to those who have better environmental quality ii. Relevant (and competing) economic models: 1. Pareto efficiency: ensure that everyone is at least as well off as before and nobody is made worse off. Distributional consequences: requires some level of fairness in pollution distribution depending on how you weigh CBA. 2. Kaldor-Hicks: the net benefit to society is all that matters, even if someone ends up doing worse off. Distributional consequences are entirely irrelevant; all that matters is social benefit. iii. Factors to consider when allocating pollution: 1. Current pollution distribution 2. Prior placement of pollution sources 3. Ensure that all parties are represented (vs. concern that mkt sources create inequality). a. Dworkin’s Pure Process approach: theory is that bad process (lack of representation) creates distributional inequity. Can fix this by (a) ensuring that all parties are represented; (b)ensuring that good info is available to all, (c) ensuring that the decision is being made at the right level. i. Good b/c it recognizes that the people most effected often have the least voice; bad b/c it only gets to equality in decisions, not to the question of controlling externalities. Also fails to take into account existing situation. b. Counter: Beene’s theory: market dynamics create distribution inequity, not unfair process. i. How to fix distributional inequity: understand current and prior distribution of pollution; recognize that any changes to distribution will shift the mkt; create other incentives or benefits to equalize the distribution. ii. Good b/c it recognizes that we can’t always fix distribution by shifting resources, but bad b/c it diminishes the importance of process. 4. Ensure good information is available to all 5. Ensure that the decision is being made at the right level 6. Inter-generational equality iv. Example of different govn’t responses: South African Bill of Rights (rt to clean environment; aspirational) vs. US exec order that sets guidelines for all agencies to consider and improve environmental considerations, but not binding. IV. Regulating Risk: a. Risk Assessment: (ideally neutral) i. Policy: 1. Issues with risk assessment: compound conservatism (risk models are often very conservative; enviro community vs. regulated community); there’s discretion/politics in the process, hard to erase all bias. 2. Can the public guide risk assessment? (Bryer) They’re bad at it b/c of lack of information, inability to understand the true nature of risk (drawn to sensational, local, and recent risks); also lack resources. a. Solutions? Educate public better, create a board of independent risk assessors. ii. Requirements for neutral risk assessment (Ruckelshaus) 1. (1) Neutral selection of risks to study (difficult/impossible in practice) 2. (2) Transparent assumptions (peer review req’d) iii. Risk assessment for toxic substances (Graham ) note the caution in this approach 1. Process: a. (1) ID the hazard (test on animals or look at long-term human exposure) b. (2) Dose-response evaluation (huge assumptions here), look at probability of adverse health effects at certain levels c. (3) Exposure assessment: how much exposure actually exists d. (4) Risk characterization: numerical estimate of health risk 2. Assumptions: people respond the same way as animals; highest possible dose w/o making an animal immediately risk has correlation to lower level that’s appropriate for humans; “doses” correlate to actual exposure; assumption of worst-case scenario; expect linear relationship. iv. Risk assessment in action: 1. Cts won’t question risk assessment analysis a. Tyson (EPA did a risk assessment for a pollutant before setting regulation; industry challenged. Ct held that it wouldn’t question a risk assessment if one was done). 2. Assume no risk until proven otherwise: rebuttable presumption of safety. a. Industrial Union Dept (Benzene case): OSHA passed a regulation for minimum safety standard of a pollutant w/o doing a valid risk assessment (attempting zero risk). Ct held that OSHA would need to prove a “significant risk” before it could use risk assessment to regulate. b. Risk Management: (usually very political) i. Approaches to risk mgmt: (generally arranged from most oversight to least oversight) 1. No risk: don’t allow any risk no matter what the costs. Good b/c it’s aspirational, but bad b/c it’s unrealistic/unachievable. 2. Cost-benefit analysis: two categories: willingness to pay (WTP) and willingness to accept (WTA); generally quite different. Note that this is the dominant tool. a. Difficulties: (a) how to value lives saved, future lives, etc.?; (b) endowment effect (once people have a resource, they value it higher than when they don’t; this makes valuation tough); (c) moral v practical objectives (CBA may say how we should do something, but doesn’t answer moral question of whether to do something regardless of cost); (d) commodifying the environment (someone will buy it). b. EPA must consider all factors in mgmt of risk and CBA: i. EDF v. EPA (Pesticide case): EPA ordered suspension of the use of a pesticide b/c it posed an imminent hazard. Ct held that the EPA must do a CBA, considering all factors in management of risk and CBA (though use of existing stock isn’t part of CBA). c. EPA must take into account all evidence i. Corrosion Proof Fittings v. EPA (Asbestos case): Ct remanded EPA consideration of asbestos ban b/c the EPA failed to take into account all the evidence and failed to promulgate the least restrictive rule as req’d by statute when no substitute exists. Held that EPA didn’t consider a less burdensome regulation; ct wanted to see more CBA calculation at intermediate levels of regulation. 3. Cost-effectiveness: manage risks where the dollar goes the furthest. Good b/c likely to see some overall net benefit to society, but bad b/c it can lead to distributional problems and some (higher) risks going unaddressed. 4. Risk-risk: in eliminating some risks, you create others; should compare risks taken away and created to determine best course of action. Good b/c it recognizes the externalities in risk mgmt, but bad b/c it can lead to a total inability to act. 5. Risk-benefit: compare risks averted to the generalized benefits achieved for society as a whole. Good b/c it recognizes all the externalities of risk management, but bad b/c of the impossibility of measuring true “costs” and “benefits.” Informational issues. 6. Regulatory budget: limit any one particular regulatory regime’s impact on industry. Good b/c it recognizes the externalities on industry and makes us aware of a noncompliance threshold, but bad b/c it prevents the reduction of pollution to the optimal level. 7. Technology standards: create standards based on what’s available. Good b/c it forces compliance w/the norm, but bad b/c it doesn’t force new/better technology. 8. Mkt regulation (Coase): determine there’s a risk, but let the mkt work it out. Good b/c it may lead to most efficient/socially optimal result, but bad b/c of lack of equality and the mkt fails to account for externalities. V. Agency deference: post-Chevron, Ct gives deference to agencies and won’t legislate.

CLEAN WATER ACT

I. Introduction and Policy: 1. Goal is to have discharge eliminated by 1985 (didn’t happen) § 101(a)1. i. Division of power among state/fed’l govn’t, w/EPA in charge of running the program § 101(b),2 (d),3 (g).4 1. Relative reliance on states: CWA relies more on states than the CAA; WQS are in state ctrl, and states can sell NPDES permits. The EPA can also deputize states. 2. States power: a. They can: set WQS, set individual pollutant levels higher than the EPA recommends (w/EPA approval, see NRDC v. EPA). b. They can’t do anything the EPA wouldn’t when deputized or enforce WQS against other states. 3. Fed’l govn’t power: a. EPA can: interpret the statute, set effluent limitations, set BPT and BAT stds, issue permits, (may be able to) decide whether to consider downstream WQS in interstate pollution cases (see Arkansas v. Oklahoma). b. EPA can’t: decide to regulate some point sources but not others. ii. Has been very effective at managing point sources, but terrible at managing nonpoint sources. II. Basic structure: all discharge of a pollutant into a navigable waterway is illegal, with exceptions. § 301(a).5 1. “Discharge… [by a point source] …” (CWA doesn’t apply to nonpoint sources) i. Applies only to point sources: 1. Point sources vs. nonpoint sources § 3016 a. Three reasons for the limitation: i. (1) political economy (creates incentives to dump on land); ii. (2) State authority (want to allow states to manage their own groundwater); iii. (3) Commerce Clause (probably most important: no congr’l power to regulate non navigable waterways b/c no cx’n to interstate commerce. b. Nonpoint sources, i. Approx 50% of pollution comes from them; likely exempted from CWA b/c of agriculture. ii. Some regulation, per § 208 and § 319 1. § 208 BMP programs (technically need EPA approval, but impotent in practice. 2. § 319:7 State govn’ts must issue reports; must also have “best management practices” and measures for controlling non-point sources. iii. Experimental regulation: EPA experimented w/WQ trading to help deal with this (would issue permits to nonpoint sources that could be traded). Problematic b/c not all pollutants are the same and it’s hard to know how much nonpoint sources are polluting/hard to monitor. 2. Effluent limitations § 301(b) a. Intro: effluent limitations on discharge of pollutants based on technology; no caps on pollution, and determination of how clean the water should be doesn’t happen until States make WQSs (see below). i. Set on an industry-by-industry basis. EPA can’t exclude industries from the effluent limit. b. Existing sources, per § 301(b)(1). i. Initially (until 1987) req’d best practicable technology (BPT) per §301(b)(1)(A)8 1. BPT: best practicable technology a. Not technology forcing; interpreted to mean “currently” available so as not to put too much of a burden on industry right away. 2. CBA analysis to find BPT: a. Req’d, but EPA can overrule it if it wants. b. Factors to consider: (1) cost in relation to pollution reduced; (2) age of equipment and facilities involved; (3) various engineering considerations; (4) “and such other factors as it deems necessary” i. Under (4), EPA can consider whatever it wants. Weyerhaueser v. Costel. 3. Effluent standards are set by class. a. DuPont v. Train (industry alleged that the Act required setting effluent limits by point source, rather than by class). ii. Now (post-1987) req’s best available technology (BAT) per § 301(b)(1)(B)9 1. BAT: Effluent limitations for categories and classes of technology economically achievable for the category or class. a. This is technology forcing; don’t need to look at what’s available, just what’s feasible (w/limited CBA) 2. CBA not req’d but can be done. 3. EPA can look to other industries for BAT if carefully considered; this is w/in the EPA’s discretion. a. Kennecott v. EPA: Industry challenged the EPA’s looking into an unrelated industry to determine the BAT for the P’s industry. Ct held that the BAT is technology forcing, and the EPA can consider evidence from other industries if they consider it carefully. c. Effluent limitations on new sources, per § 306 i. No CBA for new sources per § 306(a)10: b/c incorporating new technology into a new plant is cheaper/easier than retrofitting. 1. Requires “best demonstrated to be available” standards for performance per §306(b)(1)(B).11 a. This is a technology forcing standard. CPC Int’l v. Train (Ct held that this is technology forcing). b. Wide use isn’t req’d: American Steel and Industry. ii. New sources are exempted from having new standards imposed on them for 10 years after the introduction of the new standards per §306(d). 3. Anti-degradation: provisions in place to prevent water from getting much worse than it currently is w/o EPA review. ii. Water Quality Standards (WQS) § 303.12 State must establish (1) use of water body and (2) criteria for keeping it clean enough for the use. 1. Note that when WQSs are approved by the EPA, they become fed’l law. 2. Use: presumption is fishable/swimable; if not, have to show why a. Rebuttable presumption of fishable swimable WQS: if a state wants to go below this, it must submit a use attainability analysis (UAA); Idaho Minimg Ass’n v. Browner. b. EPA will enforce WQs if the state won’t, but the EPQ doesn’t need to do a UAA if a state fails to set WQS. 3. Criteria to meet use: states propose criteria and the EPA can approve (has guidelines) a. States can use narrative and numerical criteria. b. States are free to force technology by setting standards higher than the EPA’s (then use TMDLs to enforce, see US Steel v. Train). i. NRDC v. EPA: Ct held the state can set criteria higher than the EPA for dioxin as long as there’s a scientific basis for the decision to do so; the Ct will not resolve scientific uncertainties (i.e. level of pollutants that actually end up in people) if there’s scientific dispute about the criteria. 4. Total Max Daily Load (TMDLs) a. Under § 303(d),13 states must set TMDLs for point sources in waters not in attainment of WQS. This is the max amount of pollutant that can go into the water each day (day means day; Friends of the Earth v. EPA.) i. § 303(d)(1)(C):14 states must make a list of waters where § 301 limits are insufficient to meet WQS. ii. If state won’t make TMDLs, the EPA must act to set them. When the state does nothing at all, this is a “constructive submission” or zero and the EPA must act (San Francisco Bay Keeper v. Whitman). 1. But note that any state submission precludes constructive submission and the EPA can’t step in. This is measured by overall state action, not on a waterway-by-waterway basis. b. TMDL process: i. (1) State sets WQS for body of water ii. (2) State finds WQS not being met iii. (3) TMDL applied to point sources that limit the amount of pollution discharged (a lot more than permits). 1. States are free to use TMDLs like SIPs (in CAA) 2. States can also combine WQS criteria and TMDLs to force technology (and have high WQs). c. Problems: if water is not in attainment b/c of nonpoint sources, point sources are still on the hook; states sometimes fail to act on TMDLs and the EPA is reluctant to act on this. Also, states have incentives to not do much with TMDLs so the EPA doesn’t force any kind of compliance. 2. “Pollutant”: list of items in § 502.15 3. “Navigable waterway”: requires, for isolated waterways, hydrological connection to navigable waterway. i. Army Corps of Engineers (ACE) has the authority under § 404(a) to regulate disposal of dredging material in “navigable waters”. 1. Bayview Homes: Ct determined that “navigable waters” includes waters adjacent to and connected to waters a boat can pass through (to regulate dredge dumping). Ct held that “navigable” is of little import. 2. SWANCC: Challenge re: pond unconnected to any navigable water; Army Corps of Engineers claimed authority b/c of migratory birds that drink from the pond. Ct held that the statute was on the edge of comm. cl power, so interpreted it narrowly to avoid the const’l issue, didn’t invalidate the statute. a. Migratory bird rule: ACE interpreted its authority for jx over “waters” was expansive enough to include any wetlands that migratory birds may use (this = “all waters”). 3. Rapanos: Ct held (at least this is the opinion that’s followed; resulted in plurality) that a hydrological connection is req’d for regulation to be proper. 4. Exceptions (to applicability of § 301) i. NPDES (Nat’l Pollutant Discharge Elimination System) Permits § 40216 1. Provides for permits that are exceptions to § 301 (per (a)) a. Standard: BPT or BAT (now) 2. Allows for deputization of states in (b) 3. Exception to these permits: agricultural irrigation (forever). 4. EPA has broad discretion to consider other factors like downstate pollution (see Pt. III, infra) ii. Variances §301(c)17 1. Intro: a. Problematic: may provide avenues for favoritism in nat’l regulation. b. Floor: variances can’t be worse than the BPT standard (Crushed Stone); BAT is tech forcing, but BPT is the floor. c. Benefits of variances: permit avenue by which industries don’t have to shut down if they can’t comply. Language seems to indicate that they’re not permanent; if the operator later becomes able to afford to comply, he/she must. 2. Economic Variances from BAT § 301(c) for individual point sources, BAT only a. Need to show (1) modifications will represent the max use of technology w/in the operator’s capability and (2) will result in reasonable further progress toward elimination of pollution (EPA v. NCSA) 3. Incorporation for WQS § 301(g)18 a. Less stringent effluent standard if water quality isn’t affected, but doesn’t apply to toxins. 4. Fundamentally Different Factors Variances (FDF) § 301 (n).19 a. If some plant is different from the industry in some substantial way, variance allowed (even for toxins) i. CMA v. NRDC: SCOTUS held that FDF variances for toxic substances. Dissent said that EPA should create a new industry instead of FDF. III. Interstate Pollution 1. EPA has broad discretion in issuing § 402 permits to consider things like downstate pollution, and Cts won’t question EPA discretion. i. Arkansas v. Oklahoma: A had an effluent limit and WQS allowing for a certain amount of pollution (more allowed than in O); water flowed from A into O, O complained. Ct held that nothing stops the EPA from allowing discharge of pollutant when there’s a downstream violation; said that the EPA may consider that. 1. Note: problem with cooperative fed’lism is that the fed’l govn’t still has the final say.

CLEAN AIR ACT I. Introduction and General Info a. CAA is the floor, not the ceiling (States restain the authority to set SIPs higher than the nat’l NAAQ (see § 11620) b. Air pollutants § 108 i. Table of air pollutants ii. Provision for EPA to evaluate and add more. c. Fed’l/State power balance: i. In general: it’s up to states to regulate new and existing sources, the fed’l govn’t will regulate new sources as they come in. ii. Actual duties: 1. Fed’l govn’t duties: Establish air quality (NAAQs); oversee implementation of air quality (SIP calls and FIPs); new source review, PSD (prevention of deterioration, applying BACT to new sources in places where deterioration may result); trading programs (SO2 and VOX), nonattainment (forcing lowest achievable emissions for new sources and buybacks; interstate issues (smokestack heights, petitions to change standards of plants that cause interstate violation under § 126). 2. State govn’t duties: determine how to achieve air quality w/SIPs, SIP revisions (on SIP calls), buyback programs under PSD, and petitions under § 126(b). iii. Costs and regulatory tiering (Michigan) 1. Fed’l law is supreme, but polluters must still comply w/pollution controls over and above state regulation (e.g. § 116). a. Fed’l govn’t mandates SIP with cost effective caps to encourage trading; states have discretion on how to achieve, but trading is the only decent option. Actors can trade permits in accordance w/the fed’l directive, but they must still comport w/state directives. d. CAA v. CWA i. Regulation of quality: in CAA it’s fed, in CWA it’s state (subj to fed’l approval) ii. Ceiling v. floor: both the CAA and CWA allow states to set standards higher than nat’l recommendations II. National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQs) a. Introduction: i. Ambient air quality standards and setting regulations; EPA must ID pollutants every 5 years. 1. § 10821 says that EPA need only add pollutants w/in their discretion. 2. EPA doesn’t do this, too much litigation. a. Mass v. EPA: if there’s evidence that the EPA found that a pollutant may harm public health/welfare, can force them to regulate. Now, EPA stays quiet. ii. EPA must set NAAQs if it determines that a substance can harm public welfare. See Lead Letter. 1. This makes the EPA really hesitant to regulate and hesitant to enforce nonattainment b/c everyone is in nonattainment. iii. Primary and secondary: 1. Primary are aimed at the public health § 109(b)(1)22 2. Secondary are aimed at the public welfare § 109(b)(2)23 a. EPA never sets them b/c it doesn’t want to deal with litigation. b. Costs in NAAQs i. Fed’l govn’t can consider risk-risk or social welfare costs. ii. Fed’l govn’t may not consider economic costs in setting NAAQs. 1. American Trucking: CAA is a no cost assessment statute; EPA can only look at public health. c. Process for setting NAAQs: (Lead Letter) i. (1) Choose sensitive subpopulation ii. (2) Come up with blood concentration level that will protect the population iii. (3) Look at ratio of pollutant that will come from the air iv. (4) Look to the amount of pollutant coming from other sources v. (5) Determine amount of substance that can be in the ambient air. d. States are supposed to comply w/NAAQs (via SIPs, see infra) i. States that are in nonattainment face certain issues, see Pt. V, infra. ii. States do, however, retain power to set standards higher than NAAQs. iii. States may not comply w/NAAQs by blowing pollution into other states/setting up factories on the border, see § 123 (and NA section, infra). III. State Implementation Procedures (SIPs) to meet NAAQs and Consequences for SIP Failures. a. SIPs: implementation procedure for state to meet the NAAQ i. States must submit them to the EPA for approval under § 110(a).24 ii. SIP must prevent deterioration of air quality in other states under § 110(d) iii. State options under SIPs: 1. States can consider costs § 110 (a)(2) 2. Can grant exemptions to individual plants 3. Can exempt whole industries 4. Can tax industries to reduce pollution. iv. SIPs can’t regulate (1) new sources (per NSR, this is left to the fed’l govn’t); (2) sources regulated by EPA pursuant to § 126 petition, (3) HAPs (completely fed’l); (4) SO2 (nat’l trading system, states can’t impede). b. EPA approval of SIP i. Process: 1. Standard of review: good fiath effort to meet NAAQs (Union Electric) 2. EPA may not consider costs in approving/disapproving SIPs; can only look to see if the plan will meet NAAQs. Union Electric. 3. EPA may consider things like attainment and stack heights, can also consider new sources. ii. If EPA disapproves: SIP Calls: EPA can tell a state to revise its SIP. If state doesn’t revise, can issue a FIP 1. EPA can consider cost in SIP call, unlike when setting NAAQs. iii. FIPs: EPA must issue a Fed’l Implementation Procedure (FIP) if a state fails to act after 2 years on a SIP or SIPcall. IV. New Sources a. New Source Review § 111 (NSPS) i. New sources are subj to fed’l regulation (not SIPs) 1. Admin must set BAT standards for categories and classes a. BAT: standard of performance; BAT to achieve a certain reduction. CBA. b. Standards need to only be achievable, not “widely used industry standard”, Portland Cement. 2. Rationale: states were doing a bad job implementing NAAQs, so the EPA decided to take control of new sources. ii. What is a new source? § 111(a)(2) and (a)(4) 1. Building a new polluter 2. Modification (= doing anything that increases pollution) to existing source a. “Increase” – plants allowed to choose any consecutive 2 yr period in 10 yr window as their baseline. iii. Triggering review: hard to tell when it’s triggered. iv. Problems: 1. Zero sum game for plants facing modification: a. Compliance is dangerous/costly b. Asking EPA or lawyer are expensive and time consuming c. Incentive to do nothing. 2. Routine Maintenance and Repair Exception (RMRR), 40 CFR 60.14(e): a. NSR isn’t triggered w/routine maintenance. b. Factors: nature, extent, purpose, frequency, cost of modification, “other relevant factors.” Wisconsin Electric (WEPCO). If significant enough, it’s NSR (not RMRR). This is a case-by-case approach. 3. No safe harbor: Bush admin tried to create a safe harbor for changes less than 20% of cost of plant. Failed. b. Prevention of Significant Deterioration (PSD) Permits for new sources in attainment areas § 165 i. Jud’lly created doctrine (Ruckelshaus), later codified. Intended to be technology forcing. ii. Special permits for new sources in attainment areas; they must use best available control technology (BACT), as determined on a case-by-case basis. 1. PSD permits on state-by-state basis controlled by fed’l govn’t though often delegated to states. iii. Air models dictate whether PSD permits are triggered, per § 165(e)(3)(D). Problem: air models don’t accurately capture nonattainment. iv. Three categories of PSD classification: 1. Class I, where change is significant 2. Class II, where deterioration normally accompanying growth is insignificant 3. Class III where degradation up to the NAAQs would be insignificant. V. Nonattainment: a. States in nonattainment § 171 i. Issues facing states in nonattainment: 1. State must make reasonable further progress and regulate more stringently § 171, 173 a. W/new sources, must get to lowest achievable emissions rate. 2. SIP calls § 110(K) 3. State can petition the EPA to find that other states are contributing to NA § 126(b). b. New sources in nonattainment § 173 permitting program; state must purchase offsetting reduction. VI. Hazardous Air Pollutants (HAPs) a. Federally mandated control of hazardous pollutants that takes discretion totally out of states’ hands. b. EPA has to come up with a list of Hazardous air pollutants and regulate per § 112; (b) has listing of HAPs, (d) has EPA standards based on new/old sources, very stringent standards for new sources. Standard must be attainable. VII. Interstate and International Issues a. Interstate violation: i. Policy: forces consideration of externalities. 1. Deals w/Act’s inability to deal w/interstate air pollution. 2. EPA still has ability to determine if state/plant contributes “significantly” to another state’s NA a. Michigan v. EPA: the Eastern seabord was in NA for ozone; EPA focused on SIP calls to other states to reduce NOx, which contributes to the ozone; mandated cost-effective ctrl and states challenged. Ct held that the EPA may consider costs in SIP calls (not like when setting NAAQs). Said that the EPA can force a uniform reduction of a pollutant in a SIP call and establish a trading program. ii. All SIPs must include provisions to prevent nonattainment in other states per § 110(a)(2)(D), and the EPA may issue a SIP call for any reason, incl excessive interference w/another state’s pollution under § 110(K) (5). iii. Stack heights § 12325 1. States can’t dump air pollution into other states w/tall stacks. iv. Remedy for interstate violation: § 126 Petition 1. Under § 126(b), a state can petition the EPA to find that another state’s SIP violates § 110(a)(2) (D) (SIPs can’t prevent NA in other states); EPA must make a finding in 60 days. 2. EPA process (lots of discretion): a. (1) Gets to determine what a “significant” contribution is i. Jefferson County of Kentucky: border town sued another state b/c its pollution was allegedly contributing to NA. Ct held that the EPA determines if contribution is significant; if the permit in one state isn’t contributing “significantly,” the EPA won’t issue a SIP call to the first state. b. (2) EPA can deal w/a “significant” contribution by mandating reduction of pollutant in a SIP call (see Michigan v. EPA). b. International violation: i. Other countries can sue under the theory that the US is deteriorating its air quality as long as there’s a reciprocal treaty per § 115. VIII. SO2 Trading: a. Under § 402(3), fed’l govn’t issues permits that entitle the permit holder to emit one ton of SO2 b. Permits are not prop’ty, they’re currency c. Cap, permits, trading i. § 404(e): lists types of sources and how many permits they’re allowed ii. § 405: examines the rate of energy product, modifies the cap based on efficiency. d. General info: i. Trading works; has created a working cap on SO2 emissions e. Problems with trading: i. Coveting western coal (has lower SO2 content, so adverse distributional consequences); states can’t protect against this b/c of dormant commerce clause (can’t interfere w/fed’l regulation program) ii. Distributional consequences: states can’t control how pollution is distributed, to states like NY get a lot of downwind SO2 and can’t do anything about it. 1. Pataki: NY attempted to impose limits on the sales of permits, prohibiting sales of permits to upwind states where the SO2 would blow back. Ct held this was improper b/c fed’l law is supreme. iii. SO2 is the ceiling? Illinois and Pataki suggest there’s no room for state regulation in a fed’l trading program; states can’t control SO2 w/SIPS or any equivalent. 1. Illinois case: IL attempted to enforce its protectionist statute requiring Ill coal plants to buy Ill coal; Ct held this was inappropriate b/c the dormant commerce clause prevents regulating the interstate transport of coal. IX. Mobile Sources a. Regulation of mobile sources (e.g. cars) left exclusively to the fed’l govn’t. i. Preemption prevents interference: 1. Simms: state attempted to enforce fed’l emissions regulation by denying registration for owners of foreign cars that couldn’t prove compliance w/the fed’l standard; Ct held this inappropriate and said states can’t enforce fed’l law in this way. ii. Purchase restrictions are a form of regulation so states can’t enact them 1. Engine Mfr case: CA attempted to require contractors to purchase a certain number of low emissions cars. Ct held this was preemption; forcing the purchase of a certain type of car is still preempted. iii. EPA’s judgment is limited to health and welfare 1. Mass v. EPA: EPA claimed it didn’t need to regulate CO2 (its choice); Ct held that the EPA’s judgment is limited to health and welfare; can’t refuse to regulate just b/c it thinks it’s a bad idea or it doesn’t need to happen. b. Admin shall prescribe (and revise) standards applicable to the emission of any air pollutant which in his judgment contributes to air pollution that may be reasonably anticipated to endanger public health/welfare. § 202(a) i. This is a technology forcing standard ii. Foreign cars must comply § 203 c. Ceiling: i. § 209(a) says that no state can require mobile source emission standards higher than the fed’l level. ii. § 209(b)(1) – California exception: EPA can grant a waiver to CA to have its own standard (and waiver for other states that want to follow CA) as long as the standard is as protective as the fed’l standard. 1. Criteria for not granting a waiver: a. (1) EPA determines the state waiver request is arbitrary/capricious b. (2) State doesn’t need the standard to meet extraordinary/compelling cond’n c. (3) Standard wouldn’t be consistent w/§ 202. 2. Every time CA wants a new waiver, it has to apply.

NEPA

I. Purpose: a. Fed’l govn’t should promote welfare of people and well-being of future generations § 101 i. Procedural statute: 1. SCOTUS: NEPA is not substantive; Stryker & Robertson (agency need only consider environmental impact, no forced outcome). 2. But it’s semi-substantive: Calvert (holds that agency must seriously weigh costs/benefits when doing an EIS and look at legit alternatives) b. Requires fed’l agency to consider environmental impacts i. Narrow b/c it applies to the fed’l govn’t only, but broad b/c it applies to all environmental effects. c. Agency must give a reasoned response, can’t dismiss it out of hand, and bad faith is important. i. Highway case. d. Benefits: forces information to forefront and allows venue for public comment; also forces hiring of experts at agencies. II. Key issues: a. NEPA must be consistent w/the scope of the project i. Kleppe: nat’l coal mine plan w/national EISs; there was a plan to effect local EISs for each project as approved, EPA challenged for lack of regional EIS. Ct held that EIS must be consistent w/the scope of the project, no need for regional EIS when no regional plan. b. No need for NEPA action in actions that are merely proposed. Kleppe. c. Can’t break up connected or cumulative actions into separate EAs i. Cumulative actions require cumulative EISs; Thomas (forest svc did an EA w/FONSI for a logging road w/o considering the logging that would result, ct held this inappropriate, cumulative actions require cumulative EISs). ii. Connected actions: three-part test: (1) automatically trigger other actions that may require EISs; (2) can’t or will not proceed unless other actions are taken previously or simultaneously; (3) are interdependent parts of a larger action and depend on the larger action for their justification. Thomas iii. Cumulative actions: actions which, when viewed w/other proposed actions, have cumulatively significant impacts. d. When information was available: i. If information wasn’t available at the time of the EIS, the agency doesn’t have to consider it. 1. Vermont Yankee: after an EIS closed for a nuclear power plant, an environmental group raised a new alternative that wasn’t considered before. Ct held that an agency need not consider new information after an EIS is closed; it’s w/in the agency’s discretion to not reopen the EIS if the info wasn’t available at the time. ii. If information is available at the time of the EIS, the agency can choose to ignore it only after giving it a hard look. Marsch. III. Procedure: a. Either an Environmental Assessment (EA) or an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) i. Decision btwn the two: If you do an EI then conclude FONSI, you may end up having to do an EIS if you’re wrong. If you just do an EIS, greater insulation to being challenged in Ct. Therefore, if you may have to do an EIS, may just want to start off with it. EA is a gamble. ii. EA: watered down EIS; topical overview of impact. Must consider alternatives. 1. Legitimate alternatives are req’d in EA; agency can’t pick “alternatives” that are really the same things. Center for Biological Diversity v. NHSTA: P claimed EA –> FONSI was insufficient as to café standards for light trucks, said it failed b/c agency didn’t look at alternatives. iii. Draft EIS: must consider reasonable alternatives 1. Agency needn’t do an EIS for actions beyond its control. Dept of Public Transport v. Public Citizen; challenge for failure of EIS to consider certain impacts for allowing Mexican trucks into the country. Ct held that an agency needn’t do an EIS for actions beyond its control. b. If no impact, can get a finding of no significant impact (FONSI); FONSI can be challenged. i. “Significance of impact” for FONSI: two factors from Hanley: 1. (1) Comparative factor: the extent to which the action will cause adverse environmental effects in excess of those created by existing uses in the area affected by it, comparing the existing standard to what it will become. 2. (2) Absolute factor: absolute quantitative adverse environmental effects of the action itself, incl the cumulative harm that results from its contribution to existing adverse cond’ns or uses in the affected area. This may be large, doesn’t put environmental impact past any particular threshold. ii. No FONSI w/o EA 1. Hanley: plan to build a prison in NY, deteremined FONSI w/o EA, ct held that EA must be used to determine a FONSI. c. Open to notice and comment: public can add to record, agency must consider and give reasoned responses. i. Sierra Club v. ACE: ACE had a plan to build the west side highway in NY; EPA and other groups presented info of dire environmental impact during draft phase, and the ACE dismissed w/o serious consideration. Ct held that reasoned responses are req’d; an agency can’t dismiss environmental comments by saying they’re false or not the agency’s problem. d. Finalize EIS e. Potentially re-open EIS if agency decides to do so in light of new info; “hard look” std i. Marsh v. Oregon Nat’l Resources: after a final EIS was completed for a dam, an environmental group found information that was available but not considered. SCOTUS held that the standard for new info is the “hard look” – agency need not reopen EIS or do a supplement when info is brought to light if it takes a hard look at it. This is an arbitrary/capricious standard. f. Make final determination and proceed. IV. Counsel on Environmental Quality (CEQ); sets standards for agency review of NEPA (incl factors to consider and scope of projects).

CERCLA

I. Cleanup for hazardous waste sites. a. Purpose: deter irresponsible waste disposal and find deep pockets for cleanup. i. This is “back from the grave” regulation; RICRA is “cradle to grave” b. Three main kinds of liability (see also Pt. IIc, infra); owner, operator, arranger. c. Liability scheme for cleanup: i. (1) Retroactive: anyone involved before CERCLA was enacted ii. (2) Strict liability (narrow defenses) iii. (3) J/s liability: anyone involved may be liable for the full amount. d. Main questions: i. Is it waste? Focuses on solid waste ii. Is it hazardous? 1. If listed, yes. 2. Otherwise, EPA test for unlisted substances (toxic? Corrosive? Reactive? Ignitable?) II. Definitions/General info: a. Contractual relationship, innocent purchaser defense. A person who does due diligence and still winds up w/hazardous waste on site may not be liable. § 101. b. Cleanup authorization: EPA is authorized to clean up waste sites and seek compensation under § 104. i. States may also act in place of the fed’l govn’t and seek compensation. c. Liability standards § 107 i. Potentially responsible parties (PRPs) § 107(a): 1. (1) Current owner/operator (=person who decides where the waste goes) a. Owner/operator: i. Bestfood: parent company owned subsidiary that was potentially liable for waste disposal; US wanted the parent corp’n to contribute. Ct held that state PCV laws still apply to owners; can’t go after parent corp unless there’s lack of separateness or the owner “operated” the facility. b. Owner even if he didn’t do the dumping. i. NY v. Shore Realty: developer wanted to build a residential site on a toxic waste dump, knowing it was there. Ct held strict liability for owners, doesn’t matter if the owner didn’t dump the waste himself. 2. (2) Any person who owned/operated at the time of disposal 3. (3) Any person who by contract or otherwise arranged for transport or disposal – this is toughest. a. Aceto: chemical company outsourced mixing of pesticide to another company, then took it back. Company to which it outsourced dumped illegally. Ct held that arranger liability results when the owner directs what happens to the product; no “head in the sand” defense 4. (4) Any person who accepts (-ed) transport to place selected by some responsible person. ii. Defenses § 107(b): 1. Acts of God 2. Acts of War 3. Acts or omissions of third parties if D establishes that (a) due care was taken; and (b) precautions were taken against such acts or omissions. a. See innocent purchaser defense in § 101.

ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT

I. Definitions: a. Endangered: species that’s threatened to become extinct in all or significant portion of its range § 3(6) b. Taking: to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or attempt to engage in such conduct. § 3(19). i. Incl harming habitat, see Babbit. II. Protects qualifying species a. Qualifying species: sec’y of the interior lists endangered species, § 4 i. No cost considerations: 1. Tennessee Valley: NEPA runs its course and the dam is about to be opened until an endangered fish is discovered; sec’y of interior lists it as endangered. Ct holds that the dam can’t be opened, even if built, b/c it’d wipe out the endangered species. ESA is a no-cost statute. b. No govn’t funding for projects that will endanger an ES § 7. c. Private citizens can’t “take” endangered species w/o a permit, § 10. i. Babbit: privae development proposed in area near endangered species. Ct held that there’s Chevron deference to the sec’y, b/c language of “taking” is broad; sec’y was w/in his rights to read taking of habitat broadly to include harming the habitat. 1 SEC. 101. (a) The objective of this Act is to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation’s waters. In order to achieve this objective it is hereby declared that, consistent with the provisions of this Act— (1) it is the national goal that the discharge of pollutants into the navigable waters be eliminated by 1985; (2) it is the national goal that wherever attainable, an interim goal of water quality which provides for the protection and propagation of fish, shellfish, and wildlife and provides for recreation in and on the water be achieved by July 1, 1983; (3) it is the national policy that the discharge of toxic pollutants in toxic amounts be prohibited; (4) it is the national policy that Federal financial assistance be provided to construct publicly owned waste treatment works; (5) it is the national policy that areawide treatment management planning processes be developed and implemented to assure adequate control of sources of pollutants in each State; (6) it is the national policy that a major research and demonstration effort be made to develop technology necessary to eliminate the discharge of pollutants into the navigable waters, waters of the contiguous zone and the oceans; and (7) it is the national policy that programs for the control of nonpoint sources of pollution be developed and implemented in an expeditious manner so as to enable the goals of this Act to be met through the control of both point and nonpoint sources of pollution. 2 (b) It is the policy of the Congress to recognize, preserve, and protect the primary responsibilities and rights of States to prevent, reduce, and eliminate pollution, to plan the development and use (including restoration, preservation, and enhancement) of land and water resources, and to consult with the Administrator in the exercise of his authority under this Act. It is the policy of Congress that the States manage the construction grant program under this Act and implement the permit programs under sections 402 and 404 of this Act. It is further the policy of the Congress to support and aid research relating to the prevention, reduction, and elimination of pollution, and to provide Federal technical services and financial aid to State and interstate agencies and municipalities in connection with the prevention, reduction, and elimination of pollution. 3 (d) Except as otherwise expressly provided in this Act, the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (hereinafter in this Act called ‘‘Administrator’’) shall administer this Act. 4 (g) It is the policy of Congress that the authority of each State to allocate quantities of water within its jurisdiction shall not be superseded, abrogated or otherwise impaired by this Act. It is the further policy of Congress that nothing in this Act shall be construed to supersede or abrogate rights to quantities of water which have been established by any State. Federal agencies shall co-operate with State and local agencies to develop comprehensive solutions to prevent, reduce and eliminate pollution in concert with programs for managing water resources. 5 SEC. 301. (a) Except as in compliance with this section and sections 302, 306, 307, 318, 402, and 404 of this Act, the discharge of any pollutant by any person shall be unlawful. 6 SEC. 301. (a) Except as in compliance with this section and sections 302, 306, 307, 318, 402, and 404 of this Act, the discharge of any pollutant by any person shall be unlawful.

7 SEC. 319. NONPOINT SOURCE MANAGEMENT PROGRAMS. (a) STATE ASSESSMENT REPORTS.— (1) CONTENTS.—The Governor of each State shall, after notice and opportunity for public comment, prepare and submit to the Administrator for approval, a report which— (A) identifies those navigable waters within the State which, without additional action to control nonpoint sources of pollution, cannot reasonably be expected to attain or maintain applicable water quality standards or the goals and requirements of this Act; (B) identifies those categories and subcategories of nonpoint sources or, where appropriate, particular nonpoint sources which add significant pollution to each portion of the navigable waters identified under subparagraph (A) in amounts which contribute to such portion not meeting such water quality standards or such goals and requirements; (C) describes the process, including intergovernmental coordination and public participation, for identifying best management practices and measures to control each category and subcategory of nonpoint sources and, where appropriate, particular nonpoint sources identified under subparagraph (B) and to reduce, to the maximum extent practicable, the level of pollution resulting from such category, subcategory, or source; and (D) identifies and describes State and local programs for controlling pollution added from nonpoint sources to, and improving the quality of, each such portion of the navigable waters, including but not limited to those programs which are receiving Federal assistance under subsections (h) and (i). 8 (b) In order to carry out the objective of this Act there shall be achieved— (1)(A) not later than July 1, 1977, effluent limitations for point sources, other than publicly owned treatment works, (i) which shall require the application of the best practicable control technology currently available as defined by the Administrator pursuant to section 304(b) of this Act, or (ii) in the case of a discharge into a publicly owned treatment works which meets the requirements of subparagraph (B) of this paragraph, which shall require compliance with any applicable pretreatment requirements and any requirements under section 307 of this Act; and 9 (B) for publicly owned treatment works in existence on July 1, 1977, or approved pursuant to section 203 of this Act prior to June 30, 1974 (for which construction must be completed within four years of approval), effluent limitations based upon secondary treatment as defined by the Administrator pursuant to section 304(d)(1) of this Act; or

10 SEC. 306. (a) For purposes of this section: (1) The term ‘‘standard of performance’’ means a standard for the control of the discharge of pollutants which reflects the greatest degree of effluent reduction which the Administrator determines to be achievable through application of the best available demonstrated control technology, processes, operating methods, or other alternatives, including, where practicable, a standard permitting no discharge of pollutants. (2) The term ‘‘new source’’ means any source, the construction of which is commenced after the publication of proposed regulations prescribing a standard of performance under this section which will be applicable to such sources, if such standard is thereafter promulgated in accordance with this section. (3) The term ‘‘source’’ means any building, structure, facility, or installation from which there is or may be the discharge of pollutants. (4) The term ‘‘owner or operator’’ means any person who owns, leases, operates, controls, or supervises a source. (5) The term ‘‘construction’’ means any placement, assembly, or installation of facilities or equipment (including contractual obligations to purchase such facilities or equipment) at the premises where such equipment will be used, including preparation work at such premises. 11 (b)(1)(B) after a category of sources is included in a list under subparagraph (A) of this paragraph, the Administrator shall propose and publish regulations establishing Federal standards of performance for new sources within such category. The Administrator shall afford interested persons an opportunity for written comment on such proposed regulations. After considering such comments, he shall promulgate, within one hundred and twenty days after publication of such proposed regulations, such standards with such adjustments as he deems appropriate. The Administrator shall, from time to time, as technlogy and alternatives change, revise such standards following the procedure required by this subsection for promulgation of such standards. Standards of performance, or revisions thereof, shall become effective upon promulgation. In establishing or revising Federal standards of performance for new sources under this section, the Administrator shall take into consideration the cost of achieving such effluent reduction, and any non-water quality environmental impact and energy requirements. 12 WATER QUALITY STANDARDS AND IMPLEMENTATION PLANS SEC. 303. (a)(1) In order to carry out the purpose of this Act, any water quality standard applicable to interstate waters which was adopted by any State and submitted to, and approved by, or is awaiting approval by, the Administrator pursuant to this Act as in effect immediately prior to the date of enactment of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, shall remain in effect unless the Administrator determined that such standard is not consistent with the applicable requirements of this Act as in effect immediately prior to the date of enactment of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972. If the Administrator makes such a determination he shall, within three months after the date of enactment of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, notify the State and specify the changes needed to meet such requirements. If such changes are not adopted by the State within ninety days after the date of such notification, the Administrator shall promulgate such changes in accordance with subsection (b) of this section. 13 (d)(1)(A) Each State shall identify those waters within its boundaries for which the effluent limitations required by section 301(b)(1)(A) and section 301(b)(1)(B) are not stringent enough to implement any water quality standard applicable to such waters. The State shall establish a priority ranking for such waters, taking into account the severity of the pollution and the uses to be made of such waters. (B) Each State shall identify those waters or parts thereof within its boundaries for which controls on thermal discharges under section 301 are not stringent enough to assure protection and propagation of a balanced indigenous population of shellfish, fish, and wildlife. (C) Each State shall establish for the waters identified in paragraph (1)(A) of this subsection, and in accordance with the priority ranking, the total maximum daily load, for those pollutants which the Administrator identifies under section 304(a)(2) as suitable for such calculation. Such load shall be established at a level necessary to implement the applicable water quality standards with seasonal variations and a margin of safety which takes into account any lack of knowledge concerning the relationship between effluent limitations and water quality. (D) Each State shall estimate for the waters identified in paragraph (1)(D) of this subsection the total maximum daily thermal load required to assure protection and propagation of a balanced, indigenous population of shellfish, fish and wildlife. Such estimates shall take into account the normal water temperatures, flow rates, seasonal variations, existing sources of heat input, and the dissipative capacity of the identified waters or parts thereof. Such estimates shall include a calculation of the maximum heat input that can be made into each such part and shall include a margin of safety which takes into account any lack of knowledge concerning the development of thermal water quality criteria for such protection and propagation in the identified waters or parts thereof. 14 303(d)(1)(C) Each State shall establish for the waters identified in paragraph (1)(A) of this subsection, and in accordance with the priority ranking, the total maximum daily load, for those pollutants which the Administrator identifies under section 304(a)(2) as suitable for such calculation. Such load shall be established at a level necessary to implement the applicable water quality standards with seasonal variations and a margin of safety which takes into account any lack of knowledge concerning the relationship between effluent limitations and water quality. 15 GENERAL DEFINITIONS SEC. 502. Except as otherwise specifically provided, when used in this Act: (1) The term ‘‘State water pollution control agency’’ means the State agency designated by the Governor having responsibility for enforcing State laws relating to the abatement of pollution. (2) The term ‘‘interstate agency’’ means an agency of two or more States established by or pursuant to an agreement or compact approved by the Congress, or any other agency of two or more States, having substantial powers or duties pertaining to the control of pollution as determined and approved by the Adminstrator. … (6) The term ‘‘pollutant’’ means dredged spoil, solid waste, incinerator residue, sewage, garbage, sewage sludge, munitions, chemical wastes, biological materials, radioactive materials, heat, wrecked or discarded equipment, rock, sand, cellar dirt and industrial, municipal, and agricultural waste discharged into water. This term does not mean (A) ‘‘sewage from vessels or a discharge incidental to the normal operation of a vessel of the Armed Forces’’ within the meaning of section 312 of this Act; or (B) water, gas, or other material which is injected into a well to facilitate production of oil or gas, or water derived in association with oil or gas production and disposed of in a well, if the well used either to facilitate production or for disposal purpose is approved by authority of the State in which the well is located, and if such State determines that such injection or disposal will not result in the degradation of ground or surface water resources. (7) The term ‘‘navigable waters’’ means the waters of the United States, including the territorial seas. … (11) The term ‘‘effluent limitation’’ means any restriction established by a State or the Administrator on quantities, rates, and concentrations of chemical, physical, biological, and other constituents which are discharged from point sources into navigable waters, the waters of the contiguous zone, or the ocean, including schedules of compliance. (12) The term ‘‘discharge of a pollutant’’ and the term ‘‘discharge of pollutants’’ each means (A) any addition of any pollutant to navigable waters from any point source, (B) any addition of any pollutant to the waters of the contiguous zone or the ocean from any point source other than a vessel or other floating craft. (13) The term ‘‘toxic pollutant’’ means those pollutants, or combinations of pollutants, including disease-causing agents, which after discharge and upon exposure, ingestion, inhalation or assimilation into any organism, either directly from the environment or indirectly by ingestion through food chains, will, on the basis of information available to the Administrator, cause death, disease, behavioral abnormalities, cancer, genetic mutations, physiological malfunctions (including malfunctions in reproduction) or physical deformations, in such organisms or their offspring. (14) The term ‘‘point source’’ means any discernible, confined and discrete conveyance, including but not limited to any pipe, ditch, channel, tunnel, conduit, well, discrete fissure, container, rolling stock, concentrated animal feeding operation, or vessel or other floating craft, from which pollutants are or may be discharged. This term does not include agricultural stormwater discharges and return flows from irrigated agriculture. … (16) The term ‘‘discharge’’ when used without qualification includes a discharge of a pollutant, and a discharge of pollutants. 16 NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM SEC. 402. (a)(1) Except as provided in sections 318 and 404 of this Act, the Administrator may, after opportunity for public hearing, issue a permit for the discharge of any pollutant, or combination of pollutants, notwithstanding section 301(a), upon condition that such discharge will meet either (A) all applicable requirements under sections 301, 302, 306, 307, 308, and 403 of this Act, or (B) prior to the taking of necessary implementing actions relating to all such requirements, such conditions as the Administrator determines are necessary to carry out the provisions of this Act. (2) The Administrator shall prescribe conditions for such permits to assure compliance with the requirements of paragraph (1) of this subsection, including conditions on data and information collection, reporting, and such other requirements as he deems appropriate. (3) The permit program of the Administrator under paragraph (1) of this subsection, and permits issued thereunder, shall be subject to the same terms, conditions, and requirements as apply to a State permit program and permits issued thereunder under subsection (b) of this section. … 17 (c) The Administrator may modify the requirements of subsection (b)(2)(A) of this section with respect to any point source for which a permit application is filed after July 1, 1977, upon a showing by the owner or operator of such point source satisfactory to the Administrator that such modified requirements (1) will represent the maximum use of technology within the economic capability of the owner or operator; and (2) will result in reasonable further progress toward the elimination of the discharge of pollutants. 18 (g) MODIFICATIONS FOR CERTAIN NONCONVENTIONAL POLLUTANTS.— (1) GENERAL AUTHORITY.—The Administrator, with the concurrence of the State, may modify the requirements of subsection (b)(2)(A) of this section with respect to the discharge from any point source of ammonia, chlorine, color, iron, and total phenols (4AAP) (when determined by the Administrator to be a pollutant covered by subsection (b)(2)(F)) and any other pollutant which the Administrator lists under paragraph (4) of this subsection. (2) REQUIREMENTS FOR GRANTING MODIFICATIONS.—A modification under this subsection shall be granted only upon a showing by the owner or operator of a point source satisfactory to the Administrator that— (A) such modified requirements will result at a minimum in compliance with the requirements of subsection (b)(1)(A) or (C) of this section, whichever is applicable; (B) such modified requirements will not result in any additional requirements on any other point or nonpoint source; and (C) such modification will not interfere with the attainment or maintenance of that water quality which shall assure protection of public water supplies, and the protection and propagation of a balanced population of shellfish, fish, and wildlife, and allow recreational activities, in and on the water and such modification will not result in the discharge of pollutants in quantities which may reasonably be anticipated to pose an unacceptable risk to human health or the environment because of bioaccumulation, persistency in the environment, acute toxicity, chronic toxicity (including carcinogenicity, mutagenicity or teratogenicity), or synergistic propensities. … 19 (n) FUNDAMENTALLY DIFFERENT FACTORS.— (1) GENERAL RULE.—The Administrator, with the concurrance of the State, may establish an alternative requirement under subsection (b)(2) or section 307(b) for a facility that modifies the requirements of national effluent limitation guidelines or categorical pretreatment standards that would otherwise be applicable to such facility, if the owner or operator of such facility demonstrates to the satisfaction of the Administrator that— (A) the facility is fundamentally different with respect to the factors (other than cost) specified in section 304(b) or 304(g) and considered by the Administrator in establishing such national effluent limitation guidelines or categorical pretreatment standards; (B) the application— (i) is based solely on information and supporting data submitted to the Administrator during the rule making for establishment of the applicable national effluent limitation guidelines or categorical pretreatment standard specifically raising the factors that are fundamentally different for such facility; or (ii) is based on information and supporting data referred to in clause (i) and information and supporting data the applicant did not have a reasonable opportunity to submit during such rulemaking; (C) the alternative requirement is no less stringent than justified by the fundamental difference; and (D) the alternative requirement will not result in a non-water quality environmental impact which is markedly more adverse than the impact considered by the Administrator in establishing such national affluent limitation guideline or categorical pretreatment standard. (2) TIME LIMIT FOR APPLICATIONS.—An application for an alternative requirement which modifies the requirements of an effluent limitation or pretreatment standard under this sub- section must be submitted to the Administrator within 180 days after the date on which such limitation or standard is established or revised, as the case may be. (3) TIME LIMIT FOR DECISION.—The Administrator shall approve or deny by final agency action an application submitted under this subsection within 180 days after the date such application is filed with the Administrator. (4) SUBMISSION OF INFORMATION.—The Administrator may allow an applicant under this subsection to submit information and supporting data until the earlier of the date the application is approved or denied or the last day that the Administrator has to approve or deny such application. (5) TREATMENT OF PENDING APPLICATIONS.—For the purposes of this subsection, an application for an alternative requirement based on fundamentally different factors which is pending on the date of the enactment of this subsection shall be treated as having been submitted to the Administrator on the 180th day following such date of enactment. The applicant may amend the application to take into account the provisions of this subsection. (6) EFFECT OF SUBMISSION OF APPLICATION.—An application for an alternative requirement under this subsection shall not stay the applicant’s obligation to comply with the effluent limitation guideline or categorical pretreatment standard which is the subject of the application. (7) EFFECT OF DENIAL.—If an application for an alternative requirement which modifies the requirements of an effluent limitation or pretreatment standard under this subsection is denied by the Administrator, the applicant must comply with such limitation or standard as established or revised, as the case may be. (8) REPORTS.—By January 1, 1997, and January 1 of every odd-numbered year thereafter, the Administrator shall submit to the Committee on Environment and Public Works of the Senate and the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure of Representatives a report on the status of applications for alternative requirements which modify the requirements of effluent limitations under section 301 or 304 of this Act or any national categorical pretreatment standard under section 307(b) of this Act filed before, on, or after such date of enactment. 20 Sec. 116. Except as otherwise provided in sections 119 (c), (e), and (f)(as in effect before the date of the enactment of the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977), 209, 211(c)(4), and 233 (preempting certain State regulation of moving sources) nothing in this Act shall preclude or deny the right of any State or political subdivision thereof to adopt or enforce (1) any standard or limitation respecting emissions of air pollutants or (2) any requirement respecting control or abatement of air pollution; except that if an emission standard or limitation is in effect under an applicable implementation plan or under section 111 or 112, such State or political subdivision may not adopt or enforce any emission standard or limitation which is less stringent than the standard or limitation under such plan or section.

21 Sec. 108. (a)(1) For the purpose of establishing national pri- mary and secondary ambient air quality standards, the Administra- tor shall within 30 days after the date of enactment of the Clean Air Amendments of 1970 publish, and shall from time to time thereafter revise, a list which includes each air pollutant - (A) emissions of which, in his judgment, cause or contrib- ute to air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare; (B) the presence of which in the ambient air results from numerous or diverse mobile or stationary sources; and (C) for which air quality criteria had not been issued before the date of enactment of the Clean Air Amendments of 1970, but for which he plans to issue air quality criteria under this section. (2) The Administrator shall issue air quality criteria for an air pollutant within 12 months after he has included such pollutant in a list under paragraph (1). Air quality criteria for an air pollutant shall accurately reflect the latest scientific knowledge useful in indicating the kind and extent of all identifiable effects on public health or welfare which may be expected from the presence of such pollutant in the ambient air, in varying quantities. The criteria for an air pollutant, to the extent practicable, shall include information on - (A) those variable factors (including atmospheric condi- tions) which of themselves or in combination with other factors may alter the effects on public health or welfare of such air pollutant; (B) the types of air pollutants which, when present in the atmosphere, may interact with such pollutant to produce an adverse effect on public health or welfare; and (C) any known or anticipated adverse effects on welfare. (b)(1) Simultaneously with the issuance of criteria under subsection (a), the Administrator shall, after consultation with appropriate advisory committees and Federal departments and agencies, issue to the States and appropriate air pollution control agencies information on air pollution control techniques, which information shall include data relating to the cost of installation and operation, energy requirements, emission reduction benefits, and environmental impact of the emission control technology. Such information shall include such data as are available on available technology and alternative methods of prevention and control of air pollution. Such information shall also include data on alternative fuels, processes, and operating methods which will result in elimination or significant reduction of emissions. (2) In order to assist in the development of information on pollution control techniques, the Administrator may establish a standing consulting committee for each air pollutant included in a list published pursuant to subsection (a)(1), which shall be comprised of technically qualified individuals representative of State and local governments, industry, and the economic community. Each such committee shall submit, as appropriate, to the Administrator information related to that required by paragraph (1). (c) The Administrator shall from time to time review, and, as appropriate, modify, and reissue any criteria or information on control techniques issued pursuant to this section. Not later than six months after the date of the enactment of the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977, the Administrator shall revise and reissue criteria relating to concentrations of NO 2 over such period (not more than three hours) as he deems appropriate. Such criteria shall include a discussion of nitric and nitrous acids, nitrites, nitrates, nitrosamines, and other carcinogenic and potentially carcinogenic derivatives of oxides of nitrogen. (d) The issuance of air quality criteria and information on air pollution control techniques shall be announced in the Federal Register and copies shall be made available to the general public. (e) The Administrator shall, after consultation with the Secretary of Transportation, and after providing public notice and opportunity for comment, and with State and local officials, within nine months after enactment of the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1989 and periodically thereafter as necessary to maintain a continuous transportation-air quality planning process, update the June 1978 Transportation-Air Quality Planning Guidelines and publish guidance on the development and implementation of transportation and other measures necessary to demonstrate and maintain attainment of national ambient air quality standards. Such guidelines shall include information on -