Chapter 2: Moral Engagements

In ancient Greece, high in the Parnassian hills overlooking the Gulf of Corinth, was the sports complex, spa, and consulting firm known as the Oracle at Delphi. For hundreds of years it turned a good profit giving advice. This usually took the form of short poems that were notoriously ambiguous.

For example Croesus, king of Lydia, sent to know whether he should attack the nascent Persian empire. Delphi said “Invade Persia and destroy a mighty empire.” Croesus went for it, but he neglected to inquire which empire was going to be destroyed and he barely escaped being cooked alive

(Herodotus, 1972).

Arguably the most famous words of wisdom at Delphi were carved in the steps leading to

Apollo’s Temple. It said γνῶθι σεαυτόν – good advice then and now. Socrates was fond of repeating this and claimed the oracle had declared him the only Greek who understood what it meant. There is reason to believe that was true as well, since he consistently maintained that he did not know much of anything. 1

Certainly the translation we favor today is a bit twisted. We say “know yourself” as though that were a key to fulfillment. It is a multi-billion dollar industry in America, with personal spiritual guides

(sacred and secular), self-help books, television shows, online talisman and outfit shopping, and personal trainers. I think you can even buy a sweatshirt that proclaims “It’s all about me.” A lot of people believe that personal enlightenment has something to do with morality. 2

But like so much else that came up with the smoke from the hole in the ground at Delphi, we need to check our understanding very carefully. A better translation would be “know your place.”

Know where you stand in relation to others. That is a much more demanding requirement than thinking your own mind is the center of everything important. Where do we fit is a harder question because we cannot “discover” the answer through deep personal enlightenment. We are part of the pattern, and to know ourselves, we must find ourselves in the pattern.

For a very long time the ethics project has been to find rules that work for everyone all the time. There have been so many impressive contenders for that honor, all we can do is catalogue them in groups. Each seems to have left out something that requires a new theory. They overlap substantially when put in practice, but most people neither understand any of them completely nor consistently follow any. The temptation is to fall back on statements such as this: “If you just did things the way I expect you to, that is if you followed the true rules, we would all be so much happier.” For the most part we ignore this sort of thing when others say it, unless we happen to be of a similar mind or see an extrinsic advantage lurking nearby. If we choose to push back, some “ethics experts” just walk away in a huff and others give very clear reasons why they endorse their rules and why we should as well. But often we just let it go.

There is a story – most likely made up – about an American journalist embedded with Pancho

Villa in Northern Mexico shortly after the turn of the last century. After raising a ruckus in a particular village, Villa gave a short speech and the peasants threw their hats in the air, whistled, and cheered wildly. The American, who spoke very poor Spanish, asked what had happened. A fellow traveler said,

“Villa just promised that after the successful revolution, the land would be taken away from the rich and distributed justly.” The liberator-bandit spoke a few sentences more and was greeted only a slight bit less enthusiastically. Translation: “After the revolution, he will take the cattle away from the wealthy former ranchers and give them to the poor people.” A third speech; but this time there was grumbling and the peasants kicked the dust and began to move away. “Villa said he would even take the chickens away and share them equally” “It seems,” the journalist said “that the rules don’t apply so much to the chickens.” “It’s not about the chickens, my friend. Many of the peasants in this village own chickens.” Morality is a matter of perspective.

What we need are moral rules that cannot be broken. I believe there are two of them. This book is based entirely on these two points.

Point A: Everyone only and always acts to bring about his or her version of a better future

world.

Point B: Moral behavior only and always takes place in the context of others who act so as to

bring about their version of a better future world.

These are not norms like “Keep your promises” or “help your neighbors” that are often, but not always, followed. They describe the way the world works. Both points are ambidextrous because they are neither entirely descriptive nor normative. There is no “should” hidden in either case: the condition is “only and always.” As a theoretical justification for ethics, Point A is certainly narrow-mindedly tautological. As a predictor of how people will behave, including in group settings, it is very practical.

The little quibbles about altruism are sidestepped. Helping others means endorsing a world where that kind of act is valued. Judging it selfish or selfless is a third-party, retrospective characterization. Of course I am not saying that “one always does the right thing.” But I do hold that one always does what he or she believes is right at the moment. We may have hesitations or regrets, but it just makes no sense to say “I intended to do X but I thought at that very moment that Y might actually have been a better thing to do based on my then current understanding of the situation.” That is an antinomy. If we did X it is because we wanted to live in the kind of world X is intended to produce. 3 Humans are social creatures. And we do not have much choice in that matter either. We would not live long, let alone well, in the absence of continual interactions with others. The widespread practice throughout most of history of “exposing” unwanted children, and sometimes the elderly, was nothing more than causing their certain, prompt death by depriving them of human contact. Further, if we could think of a person living in complete isolation for any meaningful period of time, his or her morality would not be an issue worth worrying about. We could treat everybody else or just some people as though they were not moral agents, as though their future did not matter to them. But that would be moral suicide. Imagine living in a world where everyone treated us that way. We and others want to live in a world where our actions matter to what is possible for both ourselves and others. 4

Point B simply reflects Point A back into the human world. Point B is also not a norm or appeal for what somebody thinks folks should but might not do: it describes how the world of human relations works.

Neither Point A nor Point B stands alone. 5 Their moral power comes from their interconnectivity. 6 Notice that Point A is nested in an essential way in Point B. Those we must deal with have exactly the same moral status as agents that we do. They affect whether we can reach our version of a better future world in the same way that we affect their possibly better worlds. We cannot claim privilege based on a presumed better understanding of a superior ethical principle (one that suits our current needs) any more than others can. There can only be a mutual moral better future. This principle is known as emergence. 7 There is something in reciprocal moral agency that does not exist in either my solo ethical rule following or in the isolated ethical rule following of others.

It would be difficult indeed to imagine how one could break the rules implied by Points A and

B; together, they form a bond that first-order logic cannot penetrate. I do not intend to “prove” these points by fashioning a network of abstract concepts in which the parts mutually define each other. What good would that do? I will just illustrate them over and over again, showing how we can get a lot of useful things accomplished that way. But is not that exactly the point: together we can bring about a world that we agree is one we prefer to live in rather than any of the available alternatives. 8

There will be a lot of work needed to show how we can still make moral progress without first getting everybody to agree on what the rules are in particular situations. We many not even need to have a majority or a powerful minority that can impose its will on others. It will require tremendous effort to convince some that they do not have a privileged point of view. It has never been fashionable to accept that everyone has exactly the same moral status we do. We are also fond of saying that some people make moral mistakes which we have the duty to correct, but the notion of being correct more often than being corrected is pure presumption.

The project will take up Point A beginning in Chapter 7, starting with an analysis of what it means to want a better future world and how we structure the moral choices we make. The wisdom of choosing well together is the substance of Chapters 3 through 6. The final two chapters revisit the futility of pinning our hopes on abstract ethical principles and show how a common better future world is in fact emerging. The current chapter will sketch how this program works in basic form and provide a few simple illustrations.

The Structure of Moral Engagements

I want to move morality away from the theoretical, away from the individual, and to mutually interdependent action intended to maximize common human thriving. The unit of analysis in traditional ethics is the individual and the norm. The moral engagement will be my unit of analysis. 9

These are situations where individuals have the potential to influence both their own future and the future of others based on the action they choose and they recognize that the others in the engagement also have the same sort of potential. Engagements entail interlocking moral futures.

Moral engagements have a different quality or “feel” than ethical norms. We can wrestle with our conscience in personal anguish, weigh tenets with sophisticated rational precision, and consider possibilities that are mutually inconsistent or may never actually exist. We can resort to private interpretations of abstract principles as the final word until something else more final appears, and even rerun our ethical reflection after the fact until we get it comfortable in our own mind. Not so for moral behavior. Opportunities drift out of reach on their schedule not ours, we cannot unring the bell.

And regardless of the simultaneous merits of various alternatives, we can only have one at a time. It also is essential to the nature of morality that others are involved. We might be awash in opportunity to build better communities, but we cannot have all of them; we must pick the one we think is best and live with that.

In moral engagements we come together, we consider alternatives based on the circumstances nature has arranged. We consult what we want the world to be like and which alternatives seem plausible. We weigh our values, including what it would mean to conform to or skimp on various

(possibly conflicting) values. We look, as well, at the situation from the perspective of others who are involved. We appreciate that they are moral agents with the same capacity we have to take moral action, and that appreciation becomes part of our moral choice. We also realize that others’ moral agency extends to the possibility that their better world might bring ours closer or make it more remote. We are interlocked with others in moral engagements. 10 In the end, the joint pair of actions we and others take determines the futures we both enjoy and each enjoy. Our lives are a fabric of more or less continuous moral engagements, many of them semi-conscious or governed by habit. They live through them on a constant basis. They are many times more numerous than are formal ethical analyses.

The General Idea

Consider the case of Alexander Selkirk. He was a Scot born in 1676, who after a rambunctious youth went to sea as a buccaneer. He did not play well with others, and preferring his own company, asked to be put ashore on an uninhabited bit of land in the Juan Fernández Islands about 400 miles west of Chile. He survived there for four years and four months from 1704 through early 1709.

Selkirk eventually rejoined another privateer and returned to England. His adventure was popularized in a widely read interview in The Englishman, where he was mentioned in a travelogue by the captain who rescued him, Woodes Rogers, and romanticized in a poem by William Cowper.

Selkirk was certainly part of the inspiration for Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, although the location was moved to Brazil and an executive assistant named Friday was fabricated to get around 52 months of solitude that would have made for boring narrative.

Selkirk said he regularly read the Bible in his absolute solitude. But it is not obvious that he ever acted morally. No one has any direct evidence either way. Lying, cheating, and stealing were certainly out of the question. Undoubtedly he broke promises to himself. He might have had some socially unacceptable personal habits. Recently a Japanese archeologist claims to have found an old nautical instrument on one of the Juan Fernández islands, but Selkirk probably did not pollute in any material fashion. In fact, if it were not for Defoe and other rhapsodists, no one would even be giving him a thought today. He would have been a moral zero. We know nothing of what happened on the

Juan Fernández islands between 1704 and 1709; it is all made up in our minds. As it is, the ideal of Alexander Selkirk played a critical role in the western intellectual tradition.

He was one of the first symbols of the individual as rational ethical creature. The period from the latter half of the seventeenth century through the middle of the twentieth century is known as Modernism. 11

The grip of religion and tradition was pried open by scientific discoveries and the cast or serf system lost its hold, and it began to appear that enlightened individuals controlled their own destinies. The image of the world as constrained gave way to the prospect of inevitable progress, and a driving force for making the world better was Immanuel Kant’s rational individual. Jean-Jacque Rousseau invented the citizen as a free-willed person attached to a society where before there was only the peasant, merchant, priest, and so forth as “social types.” German Romanticism elevated the idealized individual to the status of hero. The novel was created at this time as a narrative of personal development. Each of us could become, at least in our imaginations, an autonomous standard of ethical virtue. Thomas

Paine’s Common Sense bolstered the American Revolution and led to the Rights of Man, the mighty document that gave the theoretical justification to the French Revolution. 12 Each man is entitled to the maximum liberty consistent with the liberty of others said John Stuart Mill. Crusoe the image (not

Selkirk the man) became the embodiment of a new understanding of our relationships with each other.

But all along Crusoe was a fiction – someone who existed only in the minds of authors, readers, and those who talk about him and what he stood for. Selkirk is the reality we all must live. After his rescue he had a dalliance, a marriage, further adventures as a privateer, and a death by yellow fever in

1721 (in addition to very brief and minor celebrity). His life on Juan Fernández was a moral void; his life after that was morally uninteresting. Our imagining of what he represented for us has been fantastic. We have to be careful not to confuse the ethical Crusoe with the morally unremarkable

Selkirk. The Formal Idea

As a general method, I work back and forth between intuitive and narrative presentations of ideas and formal and operational analyses of the same ideas. Most readers will prefer the former, but the technical expositions are there for clarification and to provide assurance that the stories are all academically grounded. The Selkirk story can be converted to testable detail.

There is a simple and distinct structure discernible across all moral actions. To illustrate this, consider the example below. We can connect Selkirk’s decision about whether he wants to leave the island and Captain Rogers’s decision about extending an opportunity to join his ship. What Selkirk does affects Rogers and the other way around. Each agent has two or more alternative courses of action. Selkirk’s world would be different if he stays or goes. The world for Rogers would be different depending on whether he took this strange man as a crew member. Choice means commitment to one course of action to the exclusion of all others. This structure captures Point A (Selkirk and Rogers act to make their worlds better) and Point B (the actions of each affect the futures of the other). What

Selkirk thought about truth telling on the 1087th day on Juan Fernández as he sat alone on the beach does not count. Whether he accepted Rogers’s offer to rejoin a privateering ship on the 1581st day did.

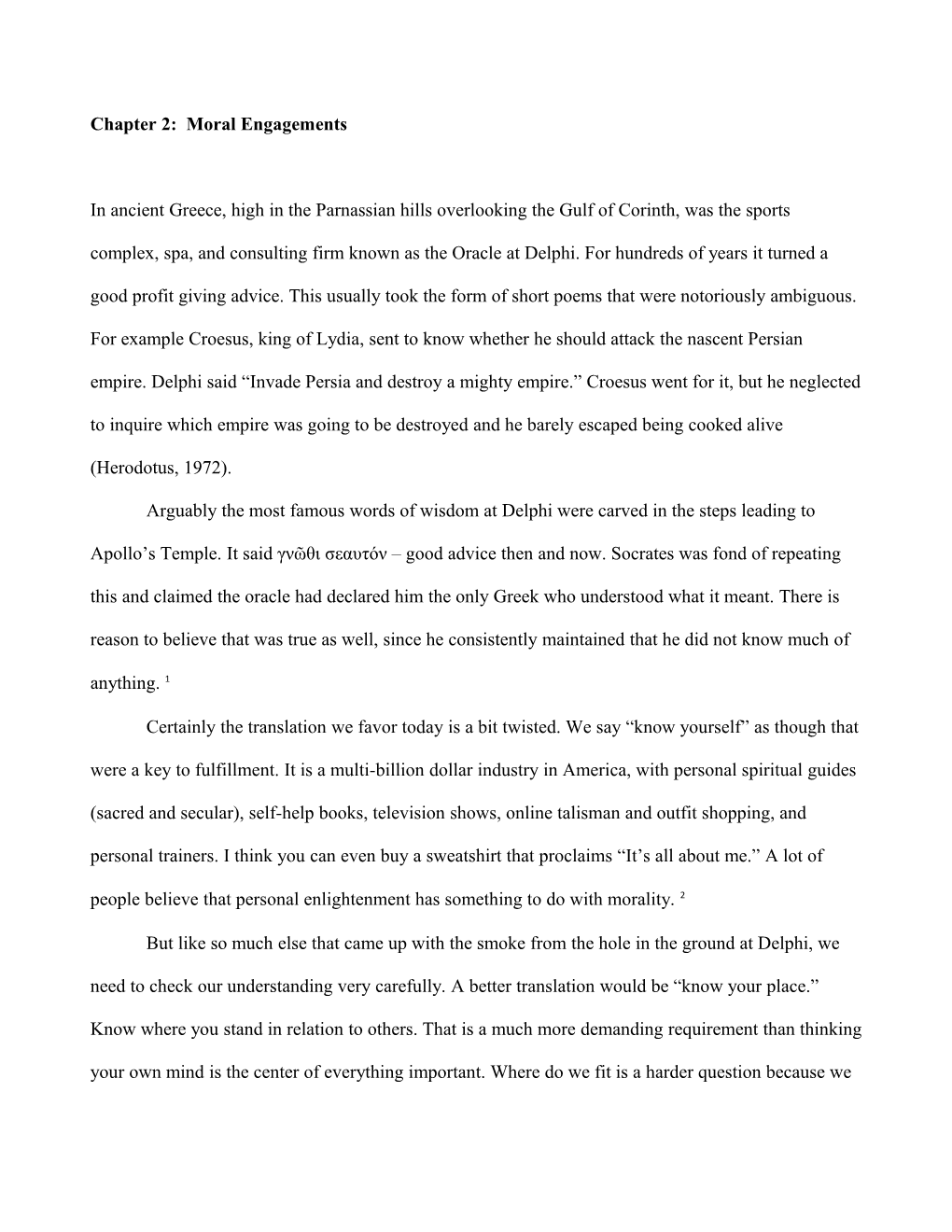

A standard way of displaying the elements of moral choice situations is depicted in Figure 2.1. Rogers’s Alternatives

“Accept Selkirk” “Reject Selkirk”

“Leave” [10 5] [1 3]

Selkirk’s Alternatives

“Stay” [ 6 2] [4 3]

Figure 2.1: Should Silkirk join Captain Rogers’s ship; should Rogers extend an invitation?

In this case there are two agents: Rogers and Selkirk. The situation has been further simplified to consider only two courses of action for each: Rogers can “accept” Selkirk or “reject” him as joining his crew, and Selkirk can either “leave” or “stay.” Selkirk cannot get back to England just because he alone thinks that would be attractive to him. The interaction between Selkirk’s and Rogers’s courses of action, technically called strategies, create four outcomes. Each outcome has a value for each agent, and these very likely are not the same. Looking at the values in the upper left-hand corner, for example, I imagine that Selkirk was overjoyed and Rogers dubiously pleased with what actually happened. Selkirk’s values are shown on an arbitrary ten-point scale and are the left-hand numbers in each of the four cells. Rogers also uses a ten-point scale, but has an independent way of valuing outcomes. These are shown on the right in each cell.

We could assume that Selkirk was a bit mixed about getting off the island and could think of a few advantages to his staying. This reflected in the [6] and [4] values. The way the moral engagement matrix has been set up, Selkirk would be devastated if he wanted to leave and Rogers turned him down. All positive and all negative considerations taken into account, Selkirk would most prefer to leave with Rogers. Although there are numbers going from [10] to [1] in this example to suggest that

Selkirk made some nuanced distinctions among the outcomes, all that is necessary is that we get clear on the rank order from most to least desirable outcome. From now on, I will only use [4] best through

[1] worst rank.

The same sort of analysis can be performed for Captain Rogers. But he consults his own values, not Selkirk’s. Does Rogers need another hand, how much food is there, what about the effect on the crew’s morale, is his reputation at stake should the story get out in England, what is this guy doing out here alone, is he crazy or perhaps dangerous? This formal approach does not preclude what are usually thought of as normative values. For example, Rogers might place high value on the altruism of helping a fellow in need. To the extent that such traditional ethical considerations figured in Rogers’s life they would boost the attractiveness of the strategic alternative of offering Selkirk a place aboard his ship. I have imagined what it would have been like to be in the captain’s position and assigned values between [10] and [1] to the four outcomes. I have given Rogers a tighter and less attractive range. In the end, the range makes no difference if we collapse these arbitrary values to ranks, and the most preferred outcome for Rogers is the one that Selkirk preferred and that both men agreed.

No one knows for certain what the values were that Selkirk and Rogers assigned to the four possible outcomes. We can make the assumption that both men chose in ways intended to maximize what they were looking for under the circumstances. All we do know for certain is that the intersection of strategies on Rogers offering and Selkirk accepting were higher in rank order preference than the other possible combinations. You or I might rank the outcomes differently, but that would not prove that we were ethically better. It would only mean that we might have ended up alone on Juan

Fernández or short one hand rather than an ethical spectator. I will consistently refer to such interactions as “moral engagements” and formal layout as a

“moral engagement matrix.” Other terms have been used such as “opportunity,” “event,” “interaction,” and most commonly “game.” 13 Using “engagement” for the critical feature of moral behavior in communities is meant to emphasize the coming together and mutually interacting part about joint choice – the engaging. It is part of the formal operationalization of Point B. Moral engagements are encounters that have the potential for changing history. Both parties care about what happens after they have recognized the potential each has to change the other’s future. 14

It would be possible to make very large matrixes depicting complex moral engagements, with numerous parties and multiple alternatives. This is an unnecessary complication and it will be explained in later chapters how the simple two-agent, two-strategy model can be used to understand more complex configurations up to nation states and historical cultural movements. Also by way of anticipation, I will make the claim here that this basic model of the 2 x 2 moral engagement will fit every possible moral situation. That claim, and the claim that this structure, when nested, explains how moral communities emerge, will unfold in the following pages.

Components of Moral Engagements

At this point it is valuable to look at each of the three components of a moral engagement: the moral agents, the alternatives, and the choices. But first a case to make things concrete. This is another example from Enlightenment individualism that is really about how people only reach their moral potential by interacting with others.

Jean Valjean as Moral Hero? Here is a story that is both poignant and uncomfortable. It is told in Victor Hugo’s (1863) book

Les Misérables, but only gets an oblique reference in the musical. The novel begins by describing how

Jean Valjean committed a petty crime of stealing bread to feed his sister’s starving family, was caught, and served 19 years in the galleys, and how, upon his release, he stole again from the household of a bishop. But the bishop recognized Valjean’s inherent goodness and refused to press charges when the thief was apprehended. There was one other minor incident of highway robbery and then the repentant

Valjean devoted seven years to reforming himself. Under an assumed name, Monsieur Madeleine, he established a successful manufacturing business, became the mayor of his town, and embraced public causes. The bishop’s faith had redeemed Valjean.

In a cruel twist of fate, a vagabond was apprehended in the nearby town of Arras in northeastern France for stealing some apples and mistakenly identified as Valjean. Valjean was still technically a fugitive from the law for the single minor highway robbery after the bishop covered for him. What an opportunity for the mayor: a person of no account will be sent to the galleys for what remained of his life as the penalty for a second offense, and the real Valjean’s new identity will be secure forever.

But that way forward does not suit Hugo’s purposes. Les Misérables and most of this mid- nineteenth century author’s works are about the noble individual who transforms the rule-driven and insensitive social order through personal heroism. Valjean is a new and improved model on the Crusoe plan. He is made to anguish between sacrificing himself and letting an innocent man suffer in his place. The struggle in the mayor’s soul is violent. The arguments line up fairly clearly along the major lines in ethical theory. 15 The utilitarian perspective of the greatest good for the greatest number pulls

Valjean toward ensuring his continued contribution to the community. Sacrificing himself on principle would impoverish the town and destroy a poor factory worker called Fantine and her daughter Cosette, the heroine of the novel. In contrast, the deontological perspective of doing one’s duty before God or ethical reason would require that Valjean go to the nearby town where the trial is in progress and offer himself as the rightful substitute for the vagabond. This is the right thing to do regardless of who else must suffer to clear Valjean’s conscience.

The conflict is perfectly balanced, and Valjean is unable to select a path. In page after page of powerfully written prose, Hugo weaves Valjean’s obsession in overcoming physical barriers blocking his getting to the trial – missed connections, broken carriage axils -- with his equally driven struggles of conscience. Still Valjean does not know what he will do. Hugo leaves us with the impression, which he later confirms, that Valjean is suffering from too much ethics. “He now recoiled with equal terror from each of the resolutions.”

The story as Hugo tells it and as I have summarized it is framed entirely in terms of ethics. The battle is taking place in a fictionalized and abstracted character’s mind. No one else knows; no one else’s life trajectory will be altered by what Valjean thinks. If anyone else matters, Valjean will speak for him or her. He has denied moral agency to all others. Fontine and Cosette are wards of Valjean’s paternalistic charity and have no independent moral standing. The vagabond is mindless and unable to participate in either his own defense or his deliverance. Only Valjean is allowed to speak in his own voice. But he cannot get a resolution that works. Valjean is Hugo’s paralyzed, free-floating, and failed ethical ego.

We can reframe the story as a moral engagement. And the matter begins to look a little clearer as soon as we allow others to participate. Valjean is one moral agent. Another is society, represented by police Inspector Javert, who is described as a “savage in the service of civilization.” Valjean can confess or remain silent. Javert can prosecute a confession or forgive it by looking the other way. Hugo has contrived the story to perfectly balance Valjean’s ethical indecision. But Javert stands firmly for exercising the rule of law. Sentimental altruists would hope for a confession and a pardon. We can certainly imagine that sort of happy ending; we can even work up reasons why that might be what ought to happen.

In following chapters it will be demonstrated that in moral engagements of this type the optimal solution is for Valjean to confess and for Javert to arrest him. That is, in fact, pretty much the direction

Hugo takes. For no reason that the hero is aware of or that Hugo explains, Monsieur Madeleine interrupts the trial to reveal his true identity and is arrested. It is not a rational choice based on any ethical principle; it is an impulse. And as we shall see, Valjean soon treacherously disavows this choice. Hugo’s masterpiece on conscience wrestling with itself allows some untidy edges to show through.

The Grammar of Morality

There is a grammar of morality just as there is a grammar of speech. 16 These conventions tell others, in a continuous fashion that is difficult to conceal, about our relationships with each other and whether we are “playing by the speech rules of our community.” Just as we cannot speak without proper or improper grammar, neither can we act without assuming a moral posture, or an immoral one.

The diagram in Figure 2.2 helped me immensely in high school French. 17 It works for virtually all languages. The structure of ordinary sentences carries information about who we are talking with and what we believe our relationships are. Not only must we choose pronouns according to this diagram, but the verbs and sometimes the nouns are modified to be consistent with this schema. We literally cannot communicate without signaling where we stand (morally) in the community.

Singular Plural

First person I, me We, us

Second person High status, informal Low status, Formal

Third person He, she , it They

Figure 2.2: The grammar of morality.

The singular and plural columns are about whether the speaker is addressing or speaking on behalf of one person or many. But the second-person position, the middle row, is anomalous. It is not about “number” at all; it is about relationship. We signal formality and status by our use of second- person pronouns. In linguistics this is known as the T-V phenomenon, from the fact that Latin-root

“singular” second-person pronouns begin with T and “plural” ones begin with V. 18 We use the T- or singular-form when addressing someone who has lower status or someone with whom we are familiar.

This is for relatives, good friends, and the family pet. The king speaks this way to everyone. The T- form says “I need not be on my guard with you.” We use the V-form in formal situations and when we want to recognize others as being strangers or having higher status. Good salesmen are always more deferential than their clients. The status-formality distinction permeates language and other forms of communication. Speaking first, interrupting, having the privilege of telling jokes (and having them laughed at), and dressing casually are the equivalent of using the T-form or informal, high status form of expression.

It is not as though we can communicate with or without disclosing relationship; all communication takes place in a moral context. We have to choose between T and V whenever we speak; we have to signal whether we consider our relationship with other to be “safe.” Morality is the framework of our relationships with others. We naturally shy away from those, or watch them more closely, who fail to observe the community rules of speech and interaction. The Greek word

“barbarian” literally meant one who cannot speak correctly. We do not welcome individuals into our community when they appear to play fast and loose with the rules we hold in common or seem to be unaware of what is expected.

The normative imperative of ethics, “You should . . . ,” is always a T-form statement, an assumption of high enough status to issue commands without having to give explanations. We think nothing of a parent telling a child what to do, but when those we consider to have no relationship with us use that tone of voice, it rankles. Few of us will surrender, even temporarily, our privilege of being an independent moral agent without either a strong inducement, a fight, or a glance around to see how to get out of the situation. There is no way to communicate with others about moral matters without revealing some hint about how much moral freedom the other has or even whether we regard them as moral agents at all. Point A is not negotiable. And Point B is inescapable.

A good place to begin moral analysis is the upper left-hand corner of Figure 2.2, with the individual and personal perspective. There is a primitive authenticity in saying “I am appalled by stories of child molestation” or “I promise to be a loving and faithful husband as long as we both shall live.” 19 The value judgment and the act of promising are self-warranting – they are intrinsically real.

Subsequent situations may call for reconsideration, but they do not cancel the first-person singular perspective. Another could challenge, “I don’t believe you,” but that is their first-person singular position. We could say “I changed my mind,” but that is my present view of a previous situation.

The first-person singular may be the right starting point, but it is a dead end unless it connects to others and creates some form of moral community. The dividing line between ethics and morality is whether one completes the connection by turning south in Figure 2.2 to “it” language or goes right to

“we” language. (It is that Platonic first wrong step business that appeared in Chapter 1 all over again.)

Ethics hopes to cloak the personal perspective in the impersonal “it” on the bottom left. There is a difference between saying “I believe that . . .” (in the sense that my view of the world is such that I am prepared to act in a particular manner) and “It is true that . . .” (in the sense that something is so regardless of what anyone might think). Naturally, we prefer to defend our personal preferences by hooking them to unchallengeable verities. It is comforting to say “I am right” – not just “I believe my behavior is the most appropriate for me under the circumstances.” The ancient formula “It is written” reflects what is going on when we speak from the perspective of disembodied ethical universals.

Appeal to the authority of “it” is an attempt to get a one-up position in the ethical business. We scrub off our own perspective and attribute our values to a higher position from which there is no appeal. If we can get away with substituting the universal for the personal we can claim control over other’s behavior. They are wrong, whether they realize it or not.

The antidote to this gambit is obvious: I counter by taking refuge in my own “it” and claim the right to be treated as an autonomous moral agent. We fight it out with dueling generalities, all the time realizing that this is futile since, per definition, universally true ethical principles cannot be in conflict.

Now we have three options: (a) drop the matter, (b) enjoy the exchange to see who is most clever at argumentation, or (c) harmonize our actions by seeking a pair of moral actions that neither of us would regret. 20

Option (c) is the same thing as moving to the upper right in Figure 2.2. We are taking the moral first-person plural or “we” perspective. Only one person is speaking, unless it is a committee report, but the statement is based on having taken into account both one’s own and the relevant others’ points of view. “We” statement cover you and me and our relationship. A comprehensive perspective is being suggested. Even the announcement, “We disagree on whether capital punishment is appropriate” is a positive statement of a mutually recognized disagreement that honors the views of both agents.

We can skip the disembodied “they.” It is quite possible that “they” are cited more often as the ultimate authority than are Shakespeare or the Bible. It is also true that “they” are a convenient excuse for the ambient evil in the world. But “they” are too remote for us to deal with.

The Golden Rule comes very close to capturing the search of the first-person plural joint view on morality. The part about parity or equality among moral agents is very useful. The part that does not work so well is the egocentric standard. Doing unto others as you would be done by makes you the moral standard. Everyone should play equally by the same rules, but why should they be your rules?

Just because you prefer rough treatment in sexual play and irregular liaisons, that is insufficient justification for treating everyone else as if they did. We may sincerely believe that the only determinant of success in life is personal initiative. However, you will be surprised that others who have been less fortunate in their opportunities find that political philosophy harsh and unworkable. The mirror image of the Golden Rule, the pure altruism of doing unto others as they would like to be done by, is equally inadequate but less likely to be encountered.

The proper angle of attack is the mutual “we.” Virtually everything in the book from this point on assumes the primacy of the first-person plural perspective as the moral point of view. It is not necessary to make, fake, or force agreement on principle before we can move forward together. It would be worse to have nothing to do with those with whom we differ. But we should take into account the better world others envision and what they are prepared to do about that vision as we plan our own better world.

Thinking of right and wrong exclusively from our personal point of view (especially when we dress it up as universal truth) is a common launch pad point for ethical considerations. The alternative is to regard the point of view of relevant agents as the foundation for moral action. That does not mean we subordinate others’ views to ours or ours to others’; it means we work hard to understand where both of us are coming from before we take our action. Chapter 4 will introduce this concept in a more formal sense and it will get a special name – RECIPROCAL MORAL AGENCY. This will appropriately honor

Point B, that we affect other’s futures just as they affect ours. 21

Principles and Actions

An individual may simultaneously entertain multiple and conflicting principles, but no one can engage in simultaneously contradictory actions. We can think of many reasons for and against abortions, but the pregnant woman either has one or she does not. I am commenting on something beyond the fact that ethical theorizing should eventually show up in the real world. (Actually, of course, there is no necessary reason why all our good ethical conclusions should be acted on.) The point is that ethical reasoning is a cluttered field of hypotheticals where alternative rules continue to live regardless of what we do about it. Moral life is a different kind of world where any action we take destroys all other possibilities at that moment.

Think of moral engagements as turning points in history. The choices have consequences.

Valjean’s life was changed the moment the bishop forgave him. So was the life of the unnamed individual who was mistaken for Valjean once Valjean revealed his own identity. The economy of the small town in northeastern France where Monsieur Madeleine had been mayor crumbled. Cosette, the illegitimate daughter of the factory worker that Valjean befriended, was condemned to domestic slavery. Fantine, the mother died. Javert, the bloodhound inspector, eventually committed suicide.

Most moral engagements are not so monumental. Some, such as Truman’s decision to use the atomic bomb, are so enormous groups of individuals cannot comfortably comprehend them. But all moral engagements are places where the path of history is bent, even if just a little and only at that spot.

How Are Moral Outcomes Evaluated?

We have looked at the agents and the alternatives in a moral engagement. How can we understand the outcomes? There will be several chapters coming soon to fill out this concept. But we can begin by illustrating one simple way to place values on each of the different outcomes in particular moral engagements.

Consider an everyday situation where two individuals are arranging a meeting time for one of two possible dates to discuss a mutual concern. Perhaps it is a professor and a student who wants to get feedback on a term paper, a small working group for a community program, a social date, or a real estate agent trying to show a property. We work out these sorts of situations all the time. These are all engagements of one particular class or type. We solve them so naturally in most cases that it almost seems pedantic to look into their formal structure.

Let’s say that the two available times for meeting are Monday afternoon and Friday afternoon.

We will call the agents Ms. Row and Mr. Column. Let’s say further that Ms. Row is strongly motivated to protect her Fridays and Mr. Column is very keen on getting the business done regardless of the day, but has a slight preference for Friday to allow more time for preparation.

Ms. Row would rank any outcome on Monday ahead of any on Friday. If she can have Friday free so much the better. Friday would be a concession if it worked for Mr. Column, but Ms. Row coming in on Friday and missing Mr. Column would be awful. Let’s assign rank orders to these outcomes as Ms. Row might see them in order from [4] for meeting on Monday to [1] for not meeting on Friday.

Mr. Column goes through the same calculations, but puts the emphasis on getting together regardless of the timing. The best outcome for Mr. Column is to meet on Friday because that would give him a bit more time to prepare. But meeting on Monday would be only slightly less desirable.

What would be frustrating would be to show up on Friday and miss Ms. Row, but even worse would be to rush and be stood up on Monday. We can assign the rank preferences for Mr. Column in the same fashion, with [4] for meeting on Friday down through [1] for missing a meeting on Monday.

The rank preferences are not the same for each agent. There is no Win-Win. This is

Engagement #24 in the Appendix. There are two compromises, each pairing a first-place rank preference for one agent with a second-place ranking for the other. But whose preference should take precedent? Power politics has an answer: the person with the lower status must give way, or if someone wants it badly enough they will sweeten the deal. Traditional ethics either has no answer or would have to stage a debate where each agent argued that she or he had a principle that should dominate. We could imagine cases where that is done, but not as a general rule. It comes down to tussling over personal preferences.

But there is a solution in the sense of moral action. The person in the weaker position needs to give a little, and this is a very stable solution. In coming chapters we will see how to diagnose such resolutions, including this particular case. It actually has to do with the ordering of the less desirable outcomes, a fact that is often overlooked in ethical theory where the battle rages for top spot, often considering only a single justification at a time. Over and over, in such circumstances, entirely subconsciously, pairs of reasonable people make these adjustments because it is better for both parties to work that way. We just “know” that the meeting will take place Monday afternoon. Think of that the next time you are merging in traffic on the freeway, requesting help, or trying to get a teenager to do something. Sometimes the moral way forward is not based on first principles but on values in the second and third rank that combine to form an overall picture. This point will be demonstrated in detail in Chapter 5.

This example is intentionally very thin on what might be considered moral content. The structure of the problem is being highlighted. A small additional amount of moral substance could be introduced by imagining that this example is about a faculty member in a university who is lax about meeting office hour obligations (playing “hooky” on Friday) or about an executive who boosts his or her status by cultivating an image of being “unavailable.” Divorces, teenage suicide, and medical malpractice lawsuits have a common core of breakdown in meetings to discuss differences. Modern

China emerged as part of the process where Chairman Mao agreed to meet with President Nixon.

People are starving in North Korea and killing each other in the Middle East because each side is adding preconditions for talking. In reality these preconditions that appear minor with respect to setting a meeting are major issues disguised to make others look bad in quibbling over something as obvious as agreeing to meet. In the example above, if Ms. Row and Mr. Column both insist that their primary goal be met, there would be no meeting. Sometimes ethical principle stands in the way of moral progress.

The Ethical May Not Be Moral

We left the story in Les Misérables where Valjean confessed and Javert clamped him in jail. Under a variety of analyses, that was the right thing to do. Such was the resolution Hugo wrote into his masterpiece. Well, almost. Valjean did go to jail, but then made a break, collecting a fortune in buried treasure and evading justice as a fugitive for the rest of the novel. Valjean said, in effect, “let me see if

I can be noble and get Javert to look the other way; if not I’ll reset the game and try it the other way.”

He played a double game. Reneging is one of about a dozen moral choice rules to be taken up in the next two chapters. Specifically, it is part of a set of “cheating” rules, along with deception and coercion, all of which turn out to be losers.

By way of reviewing how moral engagements work and to preview the approach for resolving those that involve deception, one last example will be worked here. Monsieur the Mayor Madeleine

(the disguise Valjean had assumed) had taken Fantine, the morally fallen factory worker he befriended, into his house because her health was failing. The Mayor had arranged with a nun to look after her.

The nun’s name was Sister Simplicity, and her singular character trait was that she had never told a lie

-- ever. In her feverish state of mind Fantine asked her when Monsieur Madeleine would make his daily visit. Sister Simplicity, who knew that the mayor had left town for the trial of the vagabond in

Arras, only smiled and said nothing. Perhaps that was not really a lie, although it was clearly intended to deflect Fantine from panic caused by not expecting to see the mayor.

Hugo’s depiction of Inspector Javert strongly outlines his character as well. He was not personally ambitious and was in many ways the most honorable of the characters in the novel. He personified law and order – the principles of abstract justice -- and “his element, the medium in which he breathed, was veneration for all authority.” Javert was exquisitely ethical. Earlier in the episode

Javert had offered to resign from the police force because he had made implications that he suspected the major was really Valjean (whom he had seen years before in the galleys). He was embarrassed when the trial in Arras started because that seemed to mean Javert had suggested false accusations. The honorable thing to do was to apologize and offer to resign. The mayor had duplicitously accepted the apology but not the resignation. Any engagement between Javert and Sister Simplicity would certainly be based on a clash between major ethical principles (honesty and respect for authority) and likely to damage one or both.

After his escape from jail, Valjean was hastily gathering important items at his house and giving last minute instructions to Sister Simplicity about the care of Fantine. They heard Javert entering the house and Valjean hid. Javert confronted the nun and asked whether Valjean was there, and Sister Simplicity responded “no.” He then asked whether the nun had seen Valjean and again she said “no.” Javert left. The nun violated her principle of truth telling and the police officer violated his duty for careful investigation. The reader, of course rejoices, thinking that is exactly the morally correct behavior – even if neither was very ethical. Had it been otherwise, the novel would have been

600 pages shorter. The hero, Valjean, reneges; the nun lies; and the evil inspector does the honorable thing. Where is the ethics in that?

In Chapter 5, I will work out in formal detail, under the heading Balanced Compromise, how we can get to the position that the most moral outcome in this situation is for both the nun and the inspector to bend a little. This is Engagement #37 in Appendix B. But we can see here the wisdom of temporizing the application of ethical ideals. Context matters, and sometimes following a single sound ethical principle is not the answer.

What kind of world did Sister Simplicity want to live in? Certainly one where truth prevailed, and especially one where her reputation for veracity was paramount. I read her as having a super- developed conscience, so there would be no difference to her whether she lied and was found out, or lied and only had to face her own conscience. Despite the fact that truth-telling was a powerful dimension in her life, it was not the entirety. She also had opinions about a good world including people such as Valjean and Fantine and the town representing a valued moral community. The sister could not have it both ways without making an assumption about Javert that she knew was unrealistic. Chance had placed her in a compromised condition, and she could see immediately that one of the controlling factors was what another person wanted as his version of the best possible future world.

Hugo’s character development of Javert is masterful. In one person he embodies the conflict of law and order and respect for human dignity. Javert was also a sloth who played by the book and showed great reverence for authority, including religious authority. The world had placed him in a position where he could not make deference to authority and catching a malefactor simultaneously top priority. He recognized that his chances of getting the future world he wanted depended, at least in part, on what Sister Simplicity did to bring about the kind of future she wanted.

It is easy enough to poke at this type of analysis. Some would say Sister Simplicity or Javert or both had their values tangled. There are people who maintain, in theory, that telling the truth is an inviolable ethical obligation – period. But I have never met anyone who acted that way. Law-and-order advocates might be quick to criticize Javert for being too trusting. Some would even argue that the situation that Hugo set up is unrealistic and we should isolate these ethical issues and manage them separately. That, of course, only happens in academic settings or political clubs. I accept all of these arguments, but only as being what ethical spectators would do in their imaginations.

What Is Special About the Structure of Moral Engagements?

All of the examples discussed so far, and in fact all that will appear in subsequent chapters, involve engagements with two agents, each of which has two available strategies. Naturally it is possible to make these cases a little more complex. Each of the agents could play multiple roles. Who are the relevant agents when a youth soccer coach has a daughter on the team? Any smart person can find more than two options in most situations, and the number of alternative interpretations is theoretically unlimited, especially if looked at from the outside.

While every moral engagement can be complixified well beyond 2 x 2, there are easier ways of meeting the requirements of the real world than going large. When there are additional parties we can treat them as a group agent and enter their impact in the cells of the framing matrix as having a common effect. When there are more than two actions, we look at the best and the next best. Chapters

7, 8, and 9 will take up these topics in greater detail, including how the moral engagement matrix is modified based on new information and how agents can negotiate the engagement that is the most reasonable one to take up. Chapter 10 will explicitly address the matter of groups acting as moral agents.

There is a deeper reason than simplicity and ease of understanding for reducing moral considerations to 2 x 2 engagements instead of larger ones. This way of framing engagements has been carefully studied for about 70 years. Twelve Nobel Prizes have been awarded to individuals who have worked on parts of this problem. Two of the prizes are important when considering the size of the engagement matrix. In 1994 John Nash, about whom the movie A Beautiful Mind was made, was awarded the prize in part for a 1951 paper in which he proved that all such 2 x 2 engagements have optimal solutions, either one or three of them. Every moral engagement has a best mutual pair of strategies for making a better world. In 1972 Kenneth Arrow (1951) was awarded a Nobel Prize for proving that conceptualizations of ethical issues with more than two principles or theoretical perspectives and more than three agents cannot be guaranteed to have solutions that all will accept.

That means it will never be possible to develop universal solutions for a better world that everyone will agree to unless we constrain ethical norms to a manageable number. But if we get the size right, we can always do it. Point of View: The Usual Ways of Looking at Ethics

In Utilitarianism, Liberty, and Representative Government, John Stuart Mill took the pragmatic view that “Government must be made for human beings as they are, or as they are capable of speedily becoming” (Mill 1910, 253). Others advocate for stretching us over the rack of ethical principles. The professional discussion of ethics is solidly normative. 22 Norms are standards for what people “should” do. Normativists say, “I am guided in the most important things in life by an abstraction, or by a handful of them, (such as fellow feeling, the will of God, political equality, or not hurting others), and you should be too.” Obviously people behave in patterns that can be characterized as though norms were involved, even when they have not been. Norms can be professed as cover – “I am doing this as a social concern” – even when the driving motive was something else. Perhaps the same pattern of actions could be characterized as expressing personal greed. Normative theories come in many flavors; there is no canonical list of norms. And the book is still open about what we can say regarding how norms affect behavior. We could, for example, probably get a good argument going over whether norms should be universal or whether they just are thought by some to be universal. There is also trouble over who should be vetting these norms and what to do with the ones that work very well, but only in special circumstances. The more we lean to the right and imagine that norms are all-explaining

“givens,” grounded in the unquestionable authority of reason, reality, or religion, the larger gap we open on the left. Now there is more work to be done explaining why some people almost all the time and most of us most of the time are so picky about our norms and so incontinent in observing the norms we publicly endorse. The market for norms in ethics has been large. 23 Utilitarianism, deontology, casuistry, Ayn

Rand’s objectivist ethics, virtue ethics, feminism, bioethics, contractarianism, care ethics, and religious approaches are all normative. They are about what one ought, in principle, to do (Wedgwood 2007).

There is also a good business in metaethics, which is about the proper subject matter of ethics.

The most serious recent alternative to normative ethics has been expressivism (Ayre 1936;

Stevenson 1962). Beginning in the 1930s, some English and American philosophers proposed that statements such as “I should not vote for a tax that unfairly advantaged large corporations” was equivalent to “I dislike such laws.” This was a happy coincidence with the “linguistic turn” in philosophy happening at that time. The claim was no longer about announcing or pointing to an abstract principle (the norm) and making a claim that it is generally bad form to permit behavior inconsistent with such a principle. Expressivists said ethical statements were entirely personal reflections of an individual’s feelings about the situation. They were face-valid and supposed to motivate others to have similar emotional responses. Emotivism has lost almost all of its steam now.

Occasionally, naturalism is suggested as an alternative to normative ethics. 24 Much of the time it is the normativists who bring this up as a straw man argument in the “is” versus “ought” debates.

Naturalism is about what is. And the normativists maintain, rightly so, that one cannot get an “ought” from an “is.” I will leave discussion of Moore’s (2004/1903) Naturalistic Fallacy as an open question until the end of Chapter 11. Here I will just raise the question whether we have a compelling need for

“oughts” at all. Might we just as well get on with saying that “oughts” are supernatural fabrications of people telling others how they would prefer they behaved? Or maybe the “oughts” are reified abstractions or names for patterns of behaviors some would prefer naturally.

Consider a woman who speaks out or takes firmer action about unwanted sexual advances in the workplace. Ethicists who hold any of the various normative theories would say there is a principle involved here, such as respect for autonomy, that has been violated, and thus the woman is within her rights to speak out. Ethical realists who believe in a world of ethical ideals are discovered rather than consented to, would say the woman is right even if she and everyone else is unaware that anything is wrong. An expressivist would frame it slightly differently. The woman is letting others know that she believes the behavior is inappropriate and she has an expectation that others will feel the same way. A naturalist would say she has a strong physiological reaction that interferes with her normal functioning

(which is actually the legal definition of hostile workplace environment), that she may engage others in rectifying the problem under suitable circumstances, and that she will expect the moral community to express sympathy and take corrective action. The naturalistic view is firm on the facts of the problem and on what will happen next, but it skips over the middle part about normative principles.

There is a slightly unsettling aspect about going beyond norms when talking about morality.

The natural and social sciences are fundamentally grounded in a hard view of the world. There is a suspicion of anything that cannot be dropped on one’s toe, except, of course, for those things that are convenient ways of talking about what can otherwise be observed by looking. If we are open to listening to naturalistic voices, philosophical claims will have to square in some way with physiological and psychological claims about behavior. Maybe thoughts can be operationalized in fMRI images, on public opinion surveys, or in patterns of behavior. We certainly can know a lot about emotions by measuring hormone levels or pupil dilation. Perhaps, after we have given a full description of which future actions an individual will take and which will be avoided, there is little additional to say about what is valued.

That is a much larger challenge than it may seem at first. As just one example, consider the classic study of morality in Hartshorne and May’s (1928) multi-year work with children summarized in

Studies in the Nature of Character. The take-home message is that Plato was wrong: the individual is a lousy unit of analysis for moral action. Children will steal pencils but not books, and they will cheat on a test but not in a game. Others will show different patterns, and the patterns will drift over time.

Individuals are morally inconsistent and in ways that are independent of ethical principles. We can only be somewhat confident in saying things about moral encounters, but we are on much thinner ice trying to say anything about the general ethical character of individuals. And there appears to be no place to stand when considering universal principles. The norms seem to have come detached from the places we like to put them. Statements such as “She is ethical” are not specific enough for serious work. The kinds of behaviors we are interested in are conditional on natural contexts.

As the title for this chapter signals, the unit of analysis for morality is not the person or the principle. It is the relationship, the moral engagement. This book is openly naturalistic. I will not argue that we should reduce normative ethics of naturalistic states. That is a red herring. My position will be that states of knowing as well as states of feeling inherently carry value dimensions. We were wrong to take them apart in the first place, so we can earn no glory by trying to put them back together. Being disgusted by unwanted sexual advances is not a theoretical construct: it is an experience. Wanting to take appropriate action when threatened or reaching to hold your grandchild is not a decision arrived at by rational consideration of norms: it is what humans naturally do. It is something we can see by looking. Our behavior in the world is inescapably value laden, and values are as natural as anything. 1 Hannah Arendt (2003) develops a morality, which she draws from comments Socrates made in the Gorgias, that what keeps us on the right path is our unwillingness to live in intimate relationship with a bad person – ourselves if we realizing we are doing immoral things.

2 Mary Ann Glendon (1991), in her Rights Talk, has pointed out how Americans have transformed

“I am sure of what I want” into “therefore I am entitle to have it,” complete with a political and legal system whose principal function is to make sure we get it.

3 Incontinence is the gap between what we think we should do and what we actually do. Few philosophers take up this question, and among those who do, some such as Hubbs (2015) seem to want to explain it away as an illusion.

4 Jürgan Habermas (1993) proposes a general rule that moral actions are those agreed to by all concerned. David Gauthier (1986), in Morals by Agreement, follows a similar line of reasoning.

5 The brilliant Cambridge logician Frank Ramsey (1964) was one of the first to articulate the view that all action is undertaken to bring about a world we value, thus fusing the concepts of action and truth.

6 Consider possible strategies to dislodge Points A and B logically. The straightforward argument against Point A is to claim “I prefer to live in a world where it is not the case that everyone acts to bring about a world they would prefer” is self-defeating. Similarly for Point B: “Moral agents prefer to live in worlds that they and others prefer, but I deny, as a moral agent, that your preference is acceptable if it includes any inconvenient claim on my preference” is equally self-defeating. Taken together, the claim that “At some level of analysis I can unilaterally truncate the emergent interaction between our mutually defining moral behaviors” is also self-defeating. Every argument that begins “I believe . . .” nests the logical analysis one level deeper and thus strips it of its objective status. Every argument that begins “It is true but I don’t believe it . . .” falls on its face.

Lewis Carroll’s (1895) dialogue between Achilles and the Tortoise proved that point.

7 The principle of emergence is woven throughout this book. It is discussed formally in the Point of View sections at the end of Chapters 8 and 10. Some useful entry points into the literature include Blitz (1992), Prigogine and Stengers (1995), and Clayton and Davies (2008).

8 The argument from design is a criticism of evolutionary theory that resembles an argument normativists might make against Points A and B. In its briefest form, the argument for design works like this: “How could we explain the beauty and purpose manifest in this particular world without assuming a ‘designer’?” The weak point in the argument is that there is no way of knowing that this world is special – others might have been better. There is a natural confusion between saying the odds of one person winning the lottery are one in a million, but the odds of someone winning it are a million in a million. Evolution did not pick it out from among other possibilities, nor need we assume that any other power did. Neither does acting to bring about worlds we would prefer require a supernatural perspective that determines what we “should” prefer.

9 Which came first: ethics or morality? This is not a “chicken or egg” question, and the answer is compellingly simple. Patterns of exchange for joint benefit governed by mutual expectations predate even the use of spoken language by hundreds of thousands or even millions of years. The codification of the rules is perhaps 15,000 years old and the isolation of these rules for intellectual consideration in general or outside the context of specific transactions is even more recent. See Will

Durant (1954), Cristina Bicchieri (1993), and Daniel Dennett (1995).

10 My definition of a moral agent is similar to the one proposed by David Wong in his (2006, 143)

Natural Moralities. Wong says: “I define moral agency as the ability to formulate reasonably clear principles among one’s moral ends, and to plan and carry out courses of action that have a reasonable chance of realizing those ends.”

11 Virtually all of ethical theory assumes the perspective of modernism, including its Newtonian linear rule-based view of a clock-work deterministic world. The strengths and limitations of modernism are sensitively handled in Passmore (1968) and Gay (1969). In the Point of View section at the end of Chapter 5, I show explicitly that we cannot escape the churning of one theoretical ethical system after another using the intellectual tools that were available before the mid-nineteenth century. 12 The French National Constitutional Assembly got the Revolution off to a start on 26 August

1789 with the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen. The basic idea was that all men are equal moral agents, limited in their freedom only by the freedom of others. Laws (actionable moral principles) are created by men in community. Among the articles are: (a) Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good. (b) The aim of all political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man.

(c) These rights are liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression. (d) Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights. These limits can only be determined by law. (e) Law can only prohibit such actions as are hurtful to society. Nothing may be prevented which is not forbidden by law, and no one may be forced to do anything not provided for by law.

13 Although I have gone to great lengths to avoid the technical language and natural prejudice associated with the unfortunate proper name of the field, it is obvious that my approach is entirely and fundamentally built on game theory. An “engagement” is a game. Nash equilibrium will be called RECIPROCAL MORAL AGENCY or RMA. While altering terminology, I have preserved every concept in the theory as faithfully as possible. Good introductions to the formal discipline can be found in the following: Luce and Raiffa (1957), Davis (1970), Maynard Smith (1982), Ordeshook

(1986), Myerson (1991), Poundstone (1992), Osborne and Rubinstein (1994), and Binmore (2007).

Binmore and Poundstone the most readable places to start. The initial efforts to ground ethics in game theory were made Richard Bevan Braithwaite (1995) and arguably the most successful has been David Gauthier’s (1986) Morals by Agreement.

14 John Stuart Mill (1859/1974, 128), in On Liberty, had this to say about moral engagements:

“What more or better can be said of any condition of human affairs than that it brings human beings themselves nearer to the best thing they can be?” 15 Utilitarianism, or more broadly, consequentialism, evaluates moral behavior by the standard of its total impact in the world. A calculation is performed, weighing all benefits and burdens of each, in Jeremy Bentham’s (1907/1832) version, allowing every person the same weight. The course of action that has the greatest net positive impact ought to be followed. The pocket version of this approach to ethics is “the greatest good for the greatest number.” Valjean’s clean conscience in Les

Misérables would count for little compared with the misery of the town without him. Deontology, the other horn of Valjean’s ethical dilemma, cleaves directly to rational or revealed ethical verities.

Principled action, regardless of its outcomes, is the standard. Valjean’s “just do the right thing” approach is what matters most. The motto of deontology is given by Kant (1949/1788), the professor of astronomy who lectured in philosophy: “Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe: . . . the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me.”

More recently, some try to split the difference. On Brad Hooker’s (1999) account, rules like “be honest” and “do not harm others” bring about a good future for most people most of the time.

16 One might regard ethics as the grammar of the moral life much as Ludwig Wittgenstein (1958) proposed that language games were the grammar of truth.

17 The T-V distinction is explained in Roger Brown’s (1965) Social Psychology. For a contemporary philosophical working out of the implications of T and V in the moral context see

Stephen Darwall (2006). Martin Buber’s I and Thou (1970) turns on this distinction.

18 English appears to be an exception to this world-wide phenomenon; we say “you” for both singular and plural. A few hundred years ago, the distinction was still present in “thee” and “thou.”

We retain the distinction, but mark it with more subtle signs such as the use of title, modes of dress, and rules of turn taking in speech.

19 J. L. Austin (1965) pointed out that sometimes words do things and sometimes they describe doing things. “The jury finds the defendant guilt” works differently from “the foreman of the jury said that the jury found the defendant guilty.” Or “strike” and “the umpire made an awful call.” I am proposing something like this with regard to the distinction between ethics and morality. “This is a stick-up” and “An armed robbery took place this afternoon in Piedmont. We should talk about the rising crime rate.”

20 Jaakko Hintikka (1962) , no doubt influenced by Wittgenstein’s visit to Cornell in 1949, argued that there is no difference between saying that X is true and saying that one believes that X is true.

Of course there is a difference between your saying you believe X is true and my saying I believe X is true. There is also a difference between “I believe X is true” and “I once believed that X is true.”

21 The question of moral progress will be developed in detail in Chapter 12. The point I want to touch here is that the possibility of moral progress depends in a fundamental way on granting moral agency to others. It also depends on abandoning the ideal of a fixed ethical structure. Progress can come both from increasing the proportion of a community guided by good norms or from a roughly similar proportion of the community following better rules. In the case of fixity through the assumption that norms had been perfected, situations arise that seem strange to our sensibilities. A famous example is Kant’s argument that women should not participate in civil discourse. He thought women lack status to participate in the development of the public good because they are not independent beings and, presumably, he thought they never would evolve to possess that capacity:

“All women . . . lack civil personality and their existence is, as it were, only inherence.” Kant

(1797/1996) The Metaphysics of Morals.

22 According to the 2009 PhilPapers online survey of philosophers, half of them said they were naturalists, but 56% also claimed to believe that ethical norms exist as real entities, independent of what anyone may think of them.

23 Alasdair MacIntyre (1967) provides an overview of the evolving history of ethics in his A Short

History of Ethics: A History of Moral Philosophy from the Homeric Age to the Twentieth Century.

24 Full-throated argument against norms as “real” entities can be found in J. L. Mackie’s (1977)

Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong, Richard Joyce’s (2002) The Myth of Morality, and Johnathan

Dancy’s (2004) Ethics without Principles. More nuanced positions are found in the quasi-realism of

Simon Blackburn (1993) and Allan Gibbard (1990).