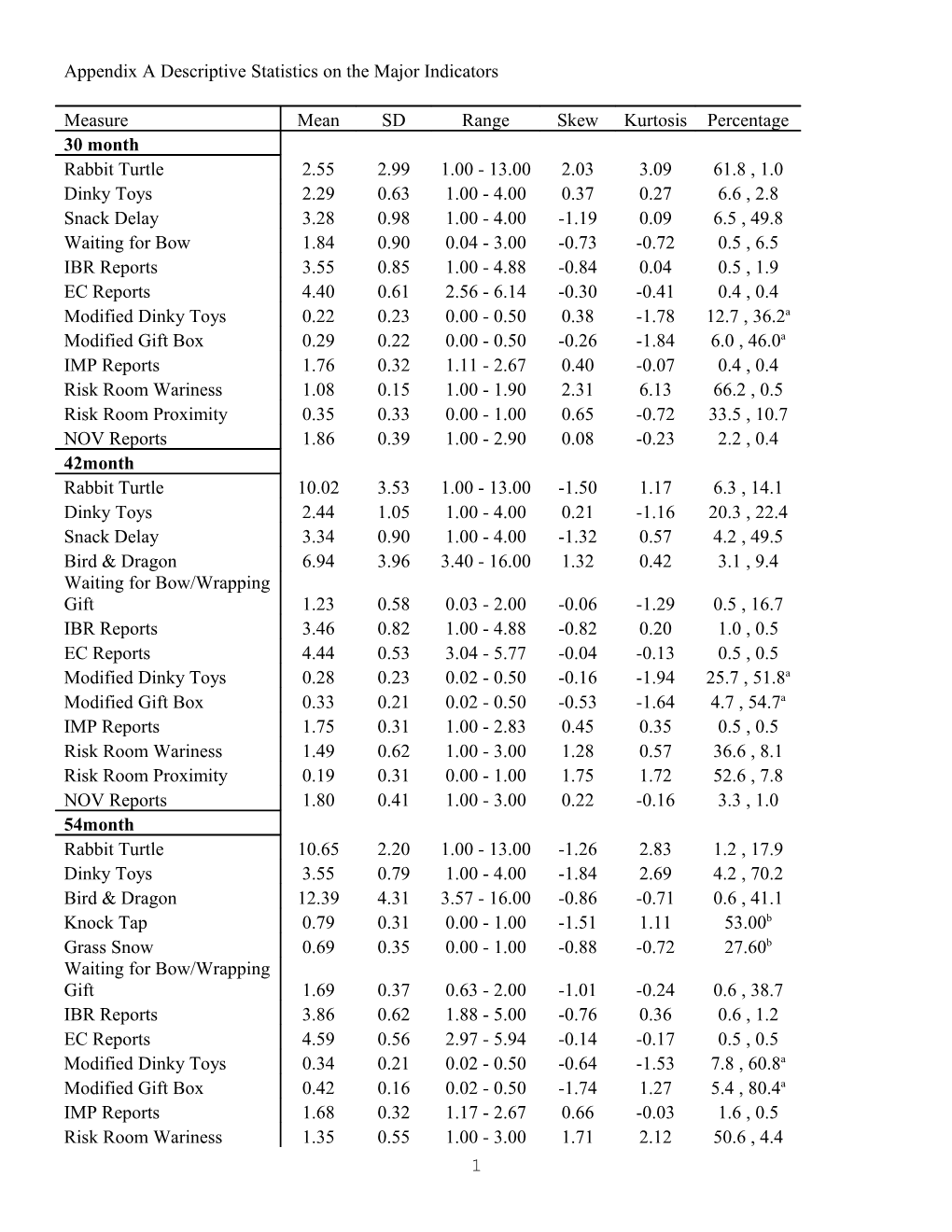

Appendix A Descriptive Statistics on the Major Indicators

Measure Mean SD Range Skew Kurtosis Percentage 30 month Rabbit Turtle 2.55 2.99 1.00 - 13.00 2.03 3.09 61.8 , 1.0 Dinky Toys 2.29 0.63 1.00 - 4.00 0.37 0.27 6.6 , 2.8 Snack Delay 3.28 0.98 1.00 - 4.00 -1.19 0.09 6.5 , 49.8 Waiting for Bow 1.84 0.90 0.04 - 3.00 -0.73 -0.72 0.5 , 6.5 IBR Reports 3.55 0.85 1.00 - 4.88 -0.84 0.04 0.5 , 1.9 EC Reports 4.40 0.61 2.56 - 6.14 -0.30 -0.41 0.4 , 0.4 Modified Dinky Toys 0.22 0.23 0.00 - 0.50 0.38 -1.78 12.7 , 36.2a Modified Gift Box 0.29 0.22 0.00 - 0.50 -0.26 -1.84 6.0 , 46.0a IMP Reports 1.76 0.32 1.11 - 2.67 0.40 -0.07 0.4 , 0.4 Risk Room Wariness 1.08 0.15 1.00 - 1.90 2.31 6.13 66.2 , 0.5 Risk Room Proximity 0.35 0.33 0.00 - 1.00 0.65 -0.72 33.5 , 10.7 NOV Reports 1.86 0.39 1.00 - 2.90 0.08 -0.23 2.2 , 0.4 42month Rabbit Turtle 10.02 3.53 1.00 - 13.00 -1.50 1.17 6.3 , 14.1 Dinky Toys 2.44 1.05 1.00 - 4.00 0.21 -1.16 20.3 , 22.4 Snack Delay 3.34 0.90 1.00 - 4.00 -1.32 0.57 4.2 , 49.5 Bird & Dragon 6.94 3.96 3.40 - 16.00 1.32 0.42 3.1 , 9.4 Waiting for Bow/Wrapping Gift 1.23 0.58 0.03 - 2.00 -0.06 -1.29 0.5 , 16.7 IBR Reports 3.46 0.82 1.00 - 4.88 -0.82 0.20 1.0 , 0.5 EC Reports 4.44 0.53 3.04 - 5.77 -0.04 -0.13 0.5 , 0.5 Modified Dinky Toys 0.28 0.23 0.02 - 0.50 -0.16 -1.94 25.7 , 51.8a Modified Gift Box 0.33 0.21 0.02 - 0.50 -0.53 -1.64 4.7 , 54.7a IMP Reports 1.75 0.31 1.00 - 2.83 0.45 0.35 0.5 , 0.5 Risk Room Wariness 1.49 0.62 1.00 - 3.00 1.28 0.57 36.6 , 8.1 Risk Room Proximity 0.19 0.31 0.00 - 1.00 1.75 1.72 52.6 , 7.8 NOV Reports 1.80 0.41 1.00 - 3.00 0.22 -0.16 3.3 , 1.0 54month Rabbit Turtle 10.65 2.20 1.00 - 13.00 -1.26 2.83 1.2 , 17.9 Dinky Toys 3.55 0.79 1.00 - 4.00 -1.84 2.69 4.2 , 70.2 Bird & Dragon 12.39 4.31 3.57 - 16.00 -0.86 -0.71 0.6 , 41.1 Knock Tap 0.79 0.31 0.00 - 1.00 -1.51 1.11 53.00b Grass Snow 0.69 0.35 0.00 - 1.00 -0.88 -0.72 27.60b Waiting for Bow/Wrapping Gift 1.69 0.37 0.63 - 2.00 -1.01 -0.24 0.6 , 38.7 IBR Reports 3.86 0.62 1.88 - 5.00 -0.76 0.36 0.6 , 1.2 EC Reports 4.59 0.56 2.97 - 5.94 -0.14 -0.17 0.5 , 0.5 Modified Dinky Toys 0.34 0.21 0.02 - 0.50 -0.64 -1.53 7.8 , 60.8a Modified Gift Box 0.42 0.16 0.02 - 0.50 -1.74 1.27 5.4 , 80.4a IMP Reports 1.68 0.32 1.17 - 2.67 0.66 -0.03 1.6 , 0.5 Risk Room Wariness 1.35 0.55 1.00 - 3.00 1.71 2.12 50.6 , 4.4 1 Risk Room Proximity 0.26 0.34 0.00 - 1.00 1.17 -0.03 43.5 , 8.9 NOV Reports 1.72 0.40 1.00 - 2.93 0.53 0.06 3.1 , 0.5 Note. Percentages are listed for the lowest score first, followed by the highest score. EC = effortful control. NOV = inhibition to novelty. IMP = impulsivity. a The scores for Modifed Dinky Toys/Gift Box are such that a low score represents high impulsivity, whereas the high score represents low impulsivity b These numbers are for the percent correct.

2 Appendix B: Supplemental Information on Reliability and Validity of Measures

EFFORTFUL CONTROL

ECBQ

The Early Childhood Behavioral Questionnaire (ECBQ; Rothbart, 2000) was utilized to assess maternal report of children's effortful control. Respondents are asked to rate the frequency of specific behaviors in their children during various typical situations. Items on each subscale are scored on a 7-point Likert-type scale from “never” to “always. Putnam, Garstein, Rothbart et al. (2006) reported alphas for attention focusing to range from .81 to .90, for attention shifting to ranger from .62 to .75, and from .86 to .90 for inhibitory control. The scales have been shown to have modest to large indices of stability over 6- and 12-month spans. In addition, scores on the ECBQ over toddlerhood were found to reflect expected developmental changes during that period (e.g., increases in attention focusing and inhibitory control, decreases in impulsivity; Putnam, et al., 2006). As further evidence of the measure’s validity, Bridgett and colleagues (2011) showed that higher maternal effortful control, higher orienting/regulation in infancy and large increases in orienting/regulation in infancy, predicted higher toddler EC as indexed by the ECBQ. In our own work, Eisenberg, Spinrad et al. (2010) showed that mothers’ and caregivers’ reports on the ECBQ were significantly correlated, and Spinrad et al. (2007) found that mothers’ and caregivers’ reports loaded together on a latent factor at 18 and 30 months of age.

Bridgett, D. J., Gartstein, M. A., Putnam, S. P., Lance, K. O., Iddins, E., Waits, R., . . . Lee, L. (2011). Emerging effortful control in toddlerhood: The role of infant orienting/regulation, maternal effortful control, and maternal time spent in caregiving activities. Infant Behavior & Development, 34(1), 189-199. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.12.008 Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., Eggum, N. D., Silva, K. M., Reiser, M. et al. (2010) Relations among maternal socialization, effortful control, and maladjustment in early childhood. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 507-525. Putnam, S. P., Gartstein, M. A., & Rothbart, M. K. (2006). Measurement of fine-grained aspects of toddler temperament: The early childhood behavior questionnaire. Infant Behavior & Development, 29(3), 386- 401. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.01.004 Rothbart, M.K. (2000). The Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire. Retrieved January 27, 2002 from University of Oregon, Mary Rothbart’s Temperament Laboratory Web site: http://www.uoregon.edu/~maryroth Spinrad, T. L., Eisenberg, N., Gaertner, B., Popp, T., Smith, C. L., Kupfer, A., . . . Hofer, C. (2007). Relations of maternal socialization and toddlers' effortful control to children's adjustment and social competence. Developmental Psychology, 43(5), 1170-1186. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.5.1170

3 CBQ

At the older ages, children’s effortful control was assessed using well-known subscales from the Child Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Rothbart & Ahadi, 1992; Rothbart, Ahadi, & Hershey, 1994; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey & Fisher, 2001). Adults’ reports were obtained for the participating children. All items were scored using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 ("Extremely untrue") to 7 ("Extremely true"). This scale was designed for parents, but we have used some subscales (with slight modifications) with teachers in about 10 studies/assessments with preschoolers, elementary, and junior high school children (Murphy, Eisenberg, Fabes, Shepard, & Guthrie, 1999; Eisenberg, Valiente, et al., 2003; 2009; Eisenberg et al., 2005). This scale is often used to assess children from 3 to 8 years of age or older (Rothbart et al., 2001). Based on data from several samples, Rothbart et al (2001) reported that all of the CBQ subscales exhibit acceptable internal reliabilities (.67 to .78). For this work, CBQ subscales measuring effortful regulation/control included attention focusing, attention shifting, and inhibitory control (attention shifting was taken from the original version of the CBQ, provided to us by Mary Rothbart, and used in the studies, for example, cited below). In our previous research using a sample of elementary school children, we found these subscales had good internal consistency for both parent and teacher reports (alphas = .81 to .88; Eisenberg, Pidada, & Liew 2001; also Eisenberg et al., 2001). Teachers' and parents' ratings on the attention focusing, attention shifting, and inhibitory control subscales tapping regulation tend to be significantly correlated (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 1996, 2000, 2001). As evidence of test-retest reliability and inter-rater reliability (for teachers), Murphy et al. (1999) found considerable consistency in parent- and teacher-report measures of regulation over a 2- to 4-year period among children ages 6-8 through 10-12. Rothbart et al. (2001) also reported evidence of consistency in parents' reports on her scales across time, and Valiente et al. (2006) also found stability in parents’ and teachers’ ratings across 2 and 4 years. As evidence of convergent validity, Kochanska, Murray, and Coy (1997) found that mothers' ratings of inhibitory control were positively related to observed levels of behavioral regulation (r = .35, p < .005) among 5- to 6-year old children. Similarly, in prior research (e.g., Eisenberg, Fabes, et al., 1995, 1997, 2000), we have found that parents’ (or teachers’) reports of one type of regulation (attention focusing) correlate positively with reports of another type of regulation (e.g., inhibitory control, attention shifting), but correlations are moderate and do not suggest problems with divergent validity. Reports on the attention focusing and inhibitory control scales also tend to correlate significantly with a behavioral measure of attentional persistence (Eisenberg, Guthrie, et al., 1997; Eisenberg, Fabes, et al, 2000; Eisenberg, Spinrad et al., 2004; Spinrad et al., 2006). As evidence of predictive validity, Rothbart et al. (1994) reported that elementary school children's levels of aggression were negatively correlated with effortful control, a composite that contained inhibitory control and attention focusing (r = -.38, p < .001). Similarly, we have found that effortful control generally predicts low externalizing problem behavior, high social competence or popularity, and high sympathy (e.g., Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al, 2001; Eisenberg, Fabes, et al., 1996, 1997, 2000; Eisenberg, Guthrie, et al., 1997, 2000; Eisenberg et al.,2001; Eisenberg et al., 2003, 2004, 2005; 2009; Valiente et al., 2003; Spinrad et al., 2006). Moreover, socially withdrawn children are low in attentional effortful control (Eggum et al., 2009). However, these correlations are modest to moderate, so these various constructs are likely distinct.

Capaldi, D. M., & Rothbart, M. K. (1992). Development and validation of an early adolescent temperament measure. Journal of Early Adolescence, 12, 153-173. Eggum, N., Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., Valiente, C., Edwards, A., Kupfer, A. S., & Reiser, M. (2009). Predictors of withdrawal: Possible precursors of avoidant personality disorder, Development and Psychopathology, 21, 815-838. Eisenberg, N., Cumberland, A. Spinrad, T. L., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S. A., Reiser, M., Murphy, B. C., Losoya, S. H., & Guthrie, I. K. (2001). The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development, 72, 1112-1134. Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Guthrie, I. K., & Reiser, M. (2000). Dispositional emotionality and regulation: Their role in predicting quality of social functioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 136-157. Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Guthrie, I. K., Murphy, B. C., Maszk, P., Holmgren, R., & Suh, K. (1996). The relations of regulation and emotionality to problem behavior in elementary school children. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 141-162.

4 Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Murphy, B., Maszk, P., Smith, M., & Karbon, M. (1995). The role of emotionality and regulation in children's social functioning: A longitudinal study. Child Development, 66, 1360-1384. Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S. A., Murphy, B. C., Guthrie, I. K., Jones, S., Friedman, J., Poulin, R., & Maszk, P. (1997). Contemporaneous and longitudinal prediction of children's social functioning from regulation and emotionality. Child Development, 68, 642-644. Eisenberg, N., Guthrie, I. K., Fabes, R. A., Reiser, M., Murphy, B. C., Holmgren, R., Maszk, P., & Losoya, S. (1997). The relations of regulation and emotionality to resiliency and competent social functioning in elementary school children. Child Development, 68, 367-383. Eisenberg, N., Guthrie, I. K., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S., Losoya, S., Murphy, B., Jones, S., Poulin, R., & Reiser, M. (2000). Prediction of elementary school children's externalizing problem behaviors from attentional and behavioral regulation and negative emotionality. Child Development, 71, 1367-1382. Eisenberg, N., Pidada, S., & Liew, J. (2001). The relations of regulation and negative emotionality to Indonesian children's social functioning. Child Development, 72. 1747-1763. Eisenberg, N., Sadovsky, A., Spinrad, T. L., Fabes, R. A., Losoya, S. H., Valiente, C., Reiser, M., Cumberland, A., & Shepard, S. A. (2005). The relations of problem behavior status to children’s negative emotionality, effortful control, and impulsivity: Concurrent relations and prediction of change. Developmental Psychology, 41, 193-211. Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., Fabes, R. A., Reiser, M., Cumberland, A., Shepard, S. A., Valiente, C., Losoya, S. H., Guthrie, I. K., & , Thompson, M. (2004). The relations of effortful control and impulsivity to children’s resiliency and adjustment. Child Development, 75, 25-46. Eisenberg, N., Valiente, C., Morris, A. S., Fabes, R. A., Cumberland, A., Reiser, M., Gershoff, E. T., Shepard, S. A., & Losoya, S. (2003). Longitudinal relations among parental emotional expressivity, children's regulation, and quality of socioemotional functioning. Developmental Psychology, 39, 2-19. Eisenberg, N., Valiente, C., Spinrad, T.L., Cumberland, A., Liew, J., Reiser, M., Zhou, Q., & Losoya, S. H. (2009). Longitudinal relations of children’s effortful control, impulsivity, and negative emotionality to their externalizing, internalizing, and co-occurring behavior problems. Developmental Psychology, 45, 988- 1008. Eisenberg, N., Zhou, Q., Spinrad, T. L., Valiente, C., Fabes, R. A., & Liew, J. (2005). Relations among positive parenting, children’s effortful control, and externalizing problems: A three-wave longitudinal study. Child Development, 76, 1055-1071. Kochanska, G., Murray, K., & Coy, K.C. (1997). Inhibitory control as a contributor to conscience in childhood: From toddler to early school age. Child Development, 68, 263-77. Murphy, B. C., Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S., & Guthrie, I. K. (1999). Consistency and change in children's emotionality and regulation: A longitudinal study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 46, 413-444. Putnam, S. P., & Rothbart, M. K. (2006). Development of short and very short forms of the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire, Journal of Personality Assessment, 87, 102-112. Rothbart, M. K. & Ahadi, S. (1992). Temperament and the development of personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103, 55-66. Rothbart, M. K., Ahadi, S. A., Hershey, K., & Fisher, P. (2001). Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The Children's Behavior Questionnaire. Child Development, 72, 1287-1604. Rothbart, M .K., Ahadi, S., & Hershey, K. L. (1994). Temperament and social behavior in childhood. Merrill- Palmer Quarterly, 40, 21-39. Spinrad, T., L., Eisenberg, N., Cumberland, A., Fabes, R. A., Valiente, C., Shepard, S. A., Reiser, M., Losoya, S. H., & Guthrie, I. K. (2006). The relations of temperamentally based control processes to children’s social competence: A longitudinal study. Emotion. 6, 498-510. Sulik, M. J., Herta, S., Zerr, A. A., Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., Valiente, C., et al. (2010). The factor structure of effortful control and measurement invariance across ethnicity and sex in a high-risk sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32, 8-22. Valiente, C., Eisenberg, N., Smith, C. L., Reiser, M., Fabes, R. A., Losoya, S., Guthrie, I. K.., & Murphy, B.C. (2003). The relations of effortful control and reactive control to children's externalizing problems: A longitudinal assessment. Journal of Personality, 71, 1179-1205. Valiente, C., Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., Reiser, M., Cumberland, A., Losoya, S. H., et al. (2006). Relations among mothers’ expressivity, children’s effortful control, and their problem behaviors: A four-year longitudinal study. Emotion, 3, 59-72.

5 Behavioral measures

The separate tasks described below most often have been combined into an effortful control composite, as in Kochanska’s many papers using these tasks (e.g., Kochanska et al., 2009). These measures are mostly quite commonly used in current studies but findings are seldom presented separately for each task.

Kochanska, G., Philibert, P. A., & Barry, R. A. (2009). Interplay of genes and early mother-child relationship in the development of self-regulation from toddler to preschool age. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50, 1331-1338.

Gift Wrap

In this task, the Experimenter brings a gift to the child as well as wrapping supplies. The child is asked to sit with his/her back to the experimenter and not to peek while the gift is being wrapped. The experimenter proceeds to pretend to wrap the gift by making noise with the tissue paper for 1 minute. This measure was associated with other measures of effortful control and Kochanska et al. (2000) created an effortful control composite that included this measure and had extremely high reliability coding (kappa = 1.00 for peeking score; 93% of latencies were within 1s and 99% were within 2s). Sulik et al (2010) found that this measure loaded with other indices of effortful control in a low-income sample and that the measures of effortful worked similarly across three ethnic groups. Toddlers improve their skills with this task between 22 and 33 months of age (Kochanska et al., 2000). Findings indicated that the effortful control composite at 33 months of age was related to more regulated anger, joy, and to stronger restraint (Kochanska et al., 2000). Li-Grining (2007) examined effortful control in a sample of preschoolers (primarily Latino and African American) from low-income families. Gift wrap was coded using three measures: how well the child waited, latency to peak, and latency to turn around. These measures were reliably coded (K = .62, ICC = .94, and ICC = .80). Mother-child connectedness was related to better effortful control (a composite of gift wrap measures and measures during another delay task). Moreover, Silva and colleagues (2011) found the gift wrap measure to load significantly on a latent construct of EC (along with knock-tap and mothers’ and teachers’ reports) using a low-income diverse sample of preschool-aged children.

Kochanska, G., Murray, K. T., & Harlan, E. T. (2000). Effortful control in early childhood: Continuity and change, antecedents, and implications for social development. Developmental Psychology, 36, 220-232. Li-Grining, C. P. (2007). Effortful control among low-income preschoolers in three cities: stability, change, and individual differences. Developmental Psychology, 43, 208-221. Silva, K. M., Spinrad, T. L., Eisenberg, N., Sulik, M. J., Valiente, C., Huerta, S. et al. (2011). Relations of children's effortful control and teacher-child relationship quality to school attitudes in a low-income sample. Early Education and Development, 22(3), 434-460. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2011.578046 Sulik, M. J., Huerta, S., Zerr, A. A., Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., Valiente, C., Di Giunta, L., Piña, A. A., Eggum, N. D., Sallquist, J., Edwards, A., Kupfer, A., Lonigan, C. J., Phillips, B. M., Wilson, S. B., Clancy- Menchetti, J., Landry, S. H., Swank, P., Assel, M., & Taylor, H. (2010). The factor structure of effortful control and measurement invariance across ethnicity and sex in a high-risk sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32(1), 8-22. doi: 10.1007/s10862-009-9164-y IF: .84

Waiting for Bow

In this task, the experimenter places a gift on the table in front of the child and asks the child to wait in his or her chair and not to touch the bag until the Experimenter comes back with a bow. The delay lasts 2 minutes. Kochanska et al (2001) created an effortful control composite that included this measure and had extremely high reliability coding (all kappas above .88). With this sample, at 30 months, we have also found extremely high reliabilities of .92 or higher on most codes. The waiting for bow measure was highly correlated

6 with the effortful control scale (Kochanska, personal communication, 10/02), and toddlers improve their skills with this task between 22 and 33 months of age (Kochanska et al., 2000). Findings indicated that the effortful control composite at 22, 33, and 45 months of age was related to higher committed compliance with the mother, particularly in “don’t” contexts (Kochanska et al., 2001). In work with this same sample, we found this measure to be positively correlated with mothers’ and caregivers’ reports of effortful control at 30, 42, and 54 months of age (Spinrad et al., 2001). In addition, toddlers who had higher scores on a different delay task (i.e., snack delay) also tended to have better delay skills in the gift bag paradigm, r(211) = .44, p < .01 (Spinrad et al., 2007). Moreover, in work with mostly minority preschool children, McCabe et al. (2004) also found this task to be useful and Sulik et al (2010) obtained evidence of configural, metric, and partial scalar invariance across three ethnic groups in a study of low-income preschoolers’ performance on this and other effortful control tasks..

Kochanska, G., Coy, K. C., & Murray, K. T. (2001). The development of self regulation in the first four years of life. Child Development, 72, 1091-1111. Kochanska, G., Murray, K. T., & Harlan, E. T. (2000). Effortful control in early childhood: Continuity and change, antecedents, and implications for social development. Developmental Psychology, 36, 220-232. McCabe, L. A., Rebello-Britto, P., Hernandez, M., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2004). Games children play: Observing young children’s self-regulation across laboratory, home, and school settings. In R. Del Carmen-Wiggins & A. Carter (Eds.). Handbook of infant, toddler, and preschool mental health assessment (pp. 491-521). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Spinrad, T. L., Eisenberg, N., & Gaertner, B. M. (2007). Measures of effortful regulation for young children. Infant Mental Health Journal, 28, 606-626. Spinrad, T. L., Eisenberg, N., Silva, K. M., Eggum, N. D., Reiser, M., Edwards, A et al. (2012). Longitudinal relations among maternal behaviors, effortful control and young children's committed compliance. Developmental Psychology, 48(2), 552-566. doi: 10.1037/a0025898 Sulik, M. J., Huerta, S., Zerr, A. A., Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., Valiente, C., Di Giunta, L., Piña, A. A., Eggum, N. D., Sallquist, J., Edwards, A., Kupfer, A., Lonigan, C. J., Phillips, B. M., Wilson, S. B., Clancy- Menchetti, J., Landry, S. H., Swank, P., Assel, M., & Taylor, H. (2010). The factor structure of effortful control and measurement invariance across ethnicity and sex in a high-risk sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32(1), 8-22. doi: 10.1007/s10862-009-9164-y IF: .84

Rabbit and Turtle

In this task, children are asked to slow down their motor activity by maneuvering a turtle (slowly) and a rabbit (fast) down along a curved path through a “meadow” to a barn. There are two trials for each. Kochanska has used this task with 33 month-old toddlers (Kochanska et al., 2000). Kochanska et al (2000) created an effortful control composite that included this measure and found that this assessment was highly correlated with the effortful control scale (Kochanska, personal communication, 10/02). Moreover, there was significant continuity in children’s effortful control from 22 to 33 months of age, r(104) = .44, p < .001. In addition, the effortful control composite converged with mothers’ and fathers’ reports of effortful control. Findings also indicated that effortful control was related to lower expressions of anger (Kochanska et al., 2000), fewer violations of maternal prohibitions (Kochanska et al., 2000), and committed compliance with the mother (Kochanska et al., 2001). In our toddler study, toddlers’ ability to negotiate the curves (i.e., whether the child followed the path with the figure) was positively related to mothers’ ratings of attentional focusing, r(196) = .18, p < .01 and was at least marginally positively related to their ability to delay during a snack delay, dinky toys, and gift delay rs(202, 199, 200) = .16 ,.16, and .13, ps < .05, .05 and .06. Moreover, this measure of motor control also was positively related to toddlers’ latency to look in the gift bag, put their hand in the bag, open the gift or leave their seat, rs(201 to 202) = .15 to .20, ps < .05 (Spinrad et al., 2007). Sulik et al (2010) obtained evidence of figural, metric, and partial invariance across three ethnic groups in a study of low-income preschoolers’ performance on this and other effortful control tasks.. Li-Grining (2007) examined executive control in a sample of preschoolers (primarily Latino and African American) from low-income families. The rabbit turtle task was coded in terms of how well the child drew paths (stayed within the lines) using an average of the two turtle trials and an average of the two rabbit trials (Ks = .

7 95 and .94). In addition, a score was calculated for the mean difference between how slow the paths for the turtle (ICC= .99) were drawn and how fast the paths for the rabbit (ICC = .98) were drawn. Sociodemographic and residential stressors related to poorer executive control (a composite of rabbit turtle measures and measures from another executive function task).

Kochanska, G., Coy, K. C., & Murray, K. T. (2001). The development of self regulation in the first four years of life. Child Development, 72, 1091-1111. Kochanska, G., Murray, K. T., & Harlan, E. T. (2000). Effortful control in early childhood: Continuity and change, antecedents, and implications for social development. Developmental Psychology, 36, 220-232. Li-Grining, C. P. (2007). Effortful control among low-income preschoolers in three cities: stability, change, and individual differences. Developmental Psychology, 43, 208-221. Spinrad, T. L., Eisenberg, N., & Gaertner, B. M. (2007). Measures of effortful regulation for young children. Infant Mental Health Journal, 28, 606-626. Sulik, M. J., Huerta, S., Zerr, A. A., Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., Valiente, C., Di Giunta, L., Piña, A. A., Eggum, N. D., Sallquist, J., Edwards, A., Kupfer, A., Lonigan, C. J., Phillips, B. M., Wilson, S. B., Clancy- Menchetti, J., Landry, S. H., Swank, P., Assel, M., & Taylor, H. (2010). The factor structure of effortful control and measurement invariance across ethnicity and sex in a high-risk sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32(1), 8-22. doi: 10.1007/s10862-009-9164-y IF: .84

Bird and Dragon

Using puppets, this task is designed to measure the child’s ability to suppress and initiate activity to signals. The child must produce a response to one type of signal while inhibiting a response to another. The experimenter explains to the child that one puppet is “nice” (a bird) whereas the other puppet is “mean” (a dragon) – the child will be instructed to only respond to the “nice” puppet. Kochanska, Coy, & Murray (2001) created an effortful control composite that included this measure and had extremely high reliability coding (all kappas above .88). Findings indicated that the effortful control composite at 22, 33, and 45 months of age was related to higher committed compliance with the mother, particularly in “don’t” contexts (Kochanska et al., 2001). This measure was chosen because of its relatively strong relation with Kochanska’s other measures of effortful control and its ability to assess relatively pure effortful control. Sulik et al (2010) obtained evidence of figural, metric, and partial invariance across three ethnic groups in a study of low-income preschoolers’ performance on this and other effortful control tasks.

Kochanska, G., Coy, K. C., & Murray, K. T. (2001). The development of self regulation in the first four years of life. Child Development, 72, 1091-1111. Sulik, M. J., Huerta, S., Zerr, A. A., Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., Valiente, C., Di Giunta, L., Piña, A. A., Eggum, N. D., Sallquist, J., Edwards, A., Kupfer, A., Lonigan, C. J., Phillips, B. M., Wilson, S. B., Clancy- Menchetti, J., Landry, S. H., Swank, P., Assel, M., & Taylor, H. (2010). The factor structure of effortful control and measurement invariance across ethnicity and sex in a high-risk sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32(1), 8-22. doi: 10.1007/s10862-009-9164-y IF: .84

Knock/Tap Task

Luria’s (1966) knock/tap test of executive functioning was used. The examiner either taps on a table with an open flat hand or raps on the table (knocks) with the knuckles of a fist. In the beginning the child has to imitate what the examiner does. After 8 trials the rule changes and the child then has to knock when the examiner taps and tap when the examiner knocks. The children’s inhibitory control score is the number of post rule change trials on which they produced the correct response (out of 8). The knock/tap task is currently used as part of a standardized neurological assessment with children (the NEPSY; Korkman, Kirk & Kemp, 1998). The NEPSY has been standardized for use with children aged 3 to 12. This task (as part of the inhibition and control subset) has been related to attention problems at school in kindergarten children (Korkman & Petlomaa, 1991). In a recent study of school-aged children with autism,

8 the knocking task was related to higher scores on another measure of executive functioning, and higher scores on theory of mind (Joseph & Tager-Flusberg, 2004). This task (or similar) has been found to change with age from 42-84 months in a nonclinical sample (Gerstadt et al., 1994) and to relate to Head Start children’s on-task behavior at school (Blair, 2003). Diamond and Taylor (1996) found that performance on this task by normal children improved with age between 3 and 6 years and children missed on average about 20% of trials. Performance was about 95% correct at 6 years, so we would have to see how the children performed at 4.5 years before deciding on using the task at older ages (Diamond and Taylor’s sample was middle class). The coding is simple and in pilot work we got kappas of .90 or higher. In a pilot study, we collected data on the knock/tap and grass/snow tasks for over 100 4-5 years old. In terms of variability, for knock/tap, 50% of children missed 1 or more trials and 40% missed at least 2 of 8 trials. For Grass/Snow, 79% missed one or more trials. Moreover, Knock/tap and grass/snow scores were significantly correlated with mothers’ ratings of effortful control (.30 and .21, ps < .01 and p < .05), caregivers’ ratings of EC (.20 and .27, ps < .05 and .01), a graduate student’s ratings of children’s attention on tasks (.38 and .36, ps < .01), and inhibition on Kochanska’s Bird and Dragon task (. 32 and .25, ps < .01). Thus, the knock/tap and grass/snow tasks do seem to relate to effortful control in a non-clinical sample.

Carlson, S. M. (2005). Developmentally sensitive measures of executive function in preschool children. Developmental Neuropsychology, 28, 595-616. Diamond, A., & Taylor, C. (1996). Development of an aspect of executive control: Development of the abilities to remember what I said and to “So as I say, not as I do.” Developmental Psychobiology, 29, 315-334. Gerstadt, C. L., Hong, Y. J., & Diamond, A. (1994). The relationship between cognition and action: Performance of children 3 1/2–7 years old on a Stroop-like day–night test. Cognition, 53, 129–153 Joseph, R. M., & Tager-Flusberg, H. (2004). The relationship of theory of mind and executive functions to symptom type and severity in children with autism. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 137-155. Korkman, M., Kirk, U., & Kemp, S. L., (1998). NEPSY. A Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX Korkman, M. & Peltomaa, K. (1991). A pattern of test findings predicting attention problems at school. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 19, 451-467. Luria, A. (1996). Higher cortical functions in man. Basic Books, N.Y.

Grass/Snow task

In this task, children are presented with a white and a green piece of construction paper and are initially instructed to point to the white piece of paper when the experimenter says "snow" and the green piece of paper when the experimenter says "grass." After a few trials, the rule changes and the child now has to point to the green piece of paper when the experimenter says "snow" and the white piece of paper when the experimenter says "grass." The percent of correct responses and latency to respond were coded. Gerstadt et al. (1994) extensively evaluated a similar task (Day and Night task) with a cross-sectional sample of children aged 42 to 84 months of age. Performance on the task increased with age. Carlson (2005) found that children’s on performance of grass/snow increased with age and that 30% of four-year-olds failed this task. Moreover, using a combined measure of executive functioning (tapping task combined with day and night task), Blair (2003) found that executive functioning was related to Head Start children’s on-task behavior at school. Lengua et al. (2007) successfully used day/night and grass/snow in a composite and this composite was related to children’s social competence across a 6 month period.

Blair, C. (2003). Behavioral inhibition and behavioral activation in young children: relations with self-regulation and adaptation to preschool in children attending Head Start. Developmental Psychobiology, 42, 301-311. Carlson, S. M. (2005). Developmentally sensitive measures of executive function in preschool children. Developmental Neuropsychology, 28, 595-616. Gerstadt, C. L., Hong, Y. J., & Diamond, A. (1994). The relationship between cognition and action: Performance of children 3 1/2–7 years old on a Stroop-like day–night test. Cognition, 53, 129–153. Lengua, L. J., Honorado, E., Bush, N. R. (2007). Contextual risk and parenting as predictors of effortful control and social competence in preschool children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 28, 40-55.

9 Infant Behavior Record (IBR)

An adapted version of the Infant Behavior Record (IBR; Bayley, 1969) was completed. The IBR was developed to capture individual differences in behavior during the administration of the Bayley; however, it has also been used to measure children’s behavior more globally (Stifter & Corey, 2001). This report was completed at the end of the laboratory visit. Four researchers (graduate student, audio-visual technicians, and experimenters) completed the attention and persistence items (1 item each) rated from 1= consistently off task or lacks persistence to 5= continued absorption in toy/activity/person or consistently persistent). Alphas for attention ranged from .74 to .84 and were from .73 to .81 for persistence (see Eisenberg, Vidmar et al., 2010). These scores significantly loaded on a latent factor of effortful control. In addition, the latent factor of effortful control significantly predicted mothers’ teaching strategies a year later, controlling for stability in the constructs, indicating child-effects on parenting behaviors (Eisenberg, Vidmar et al., 2010)

Bayley, N. (1969). The Bayley Scales of Infant Development. Training and Scoring Manual. Eisenberg, N., Vidmar, M., Spinrad, T. L., Eggum, N. D., Edwards, A., et al., (2010). Mothers’ teaching strategies and children’s effortful control: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 43, 1294- 1308. doi: 10.1037/a0020236 Stifter, C. & Corey, J. (2001). Vagal regulation and observed social behavior in infancy. Social Development, 10, 189-201.

INHIBITION TO NOVELTY

ITSEA Infant-Toddler Social & Emotional Assessment Mother & teacher reports

The Infant-Toddler Social & Emotional Assessment (ITSEA, Carter & Briggs-Gowan, 1999) was utilized to measure inhibition to novelty. Respondents are asked to indicate the presence of certain behaviors in their children on a 3-point Likert-type scale of “not true/rarely,“ “somewhat true/sometimes” and “very true/often.” Carter and Briggs-Gowan (1999) reported the alpha level for the inhibition to novelty subscale to be .77, with test-retest reliabilities of .76 within a 44-day time interval (range of 11-44 days). Maternal ratings of children’s problem behaviors on the ITSEA (the inhibition to novelty scale is a subscale of the internalizing scale) have been correlated as expected with maternal ratings of child temperament (Carter, Little, Briggs-Gowan, & Kogan, 1999); however, a low to moderate associations between the ITSEA and parent reports of temperament suggest that the ITSEA is measuring more than temperamental variation (Carter, Briggs-Gowan, Jones, & Little, 2003). In addition, the validity of this measure has been further established through correlations of its problem subscales with observational assessments of emotional regulation, coping, task mastery, and attachment in infants (Carter et al., 1999) and with evaluator ratings and parental ratings of problem behaviors (Carter et al., 2003). Using our toddler sample, Spinrad et al. (2007) found that inhibition to novelty (as measured with the ITSEA) seemed to reflect temperament more than problem behaviors. EC negatively predicted separation distress (a component of internalizing problems) but was unrelated to inhibition to novelty (and in correlations, inhibition to novelty was sometimes positively related to measures of EC).

Carter, A. & Briggs-Gowan, M. (1999). The Infant-Toddler Social & Emotional Assessment (ITSEA). Unpublished measure. Carter, A.S., Briggs-Gowan, M. J., Jones, S.M., & Little, T. D. (2003). The Infant–Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA): Factor Structure, Reliability, and Validity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31, 495–514. Carter, A., Little, C., Briggs-Gowan, M. & Kogan, N. (1999). The Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA): Comparing parent ratings to laboratory observations of task mastery, emotion regulation, coping behaviors and attachment status. Infant Mental Health Journal, 20, 375-392. Spinrad, T. L., Eisenberg, N., Gaertner, B., Popp, T., Smith, C. L., Kupfer, A, et al. (2007). Relations of 10 maternal socialization and toddlers’ effortful control to children’s adjustment and social competence. Developmental. Psychology, 43, 1170-86.

Risk room

Children’s reactive overcontrol was tapped by assessing children’s tendency to approach risky objects. This paradigm was modeled after research by Kagan (Kagan, Reznick & Gibbons, 1989). At the beginning of the laboratory visit, children were observed in an unfamiliar room containing unusual/“risky” objects (e.g., trampoline, balance beam, and scary masks tree) for two minutes. Then an unfamiliar experimenter (stranger) entered the room and attempted to coax the child into engaging with the risky objects (e.g., walking on the balance beam). During the 2 minute segment in which the child was alone in the risk room with his/her mother, latency to touch and latency to play with the first risky object was recorded (by videotape). In addition, mother involvement, communication with mother, and number of risk room objects with which the child played was globally coded. Every 10 seconds positive affect, activity level, social referencing, proximity to the mother, wariness displayed toward the objects, and number of seconds spent with risk room objects was coded. During the coaxing segment mother involvement, communication with mother, shyness toward the stranger, and enthusiasm conveyed by the stranger during coaxing was globally coded. In addition, positive affect, activity level, wariness toward the objects, whether or not the child tries the toy, cooperation with the stranger’s instructions, approaching the mother, proximity to mother, and social referencing was coded separately during the coaxing segment for each object. Kochanska, Coy, and Murray (2001) reported high interrater reliability on the coding for this paradigm (kappas ranged from .78 to .91). Children’s reactions to tasks similar to the risk room have been related to reactivity in infancy, observed wariness towards strangers at 4 years of age, and mother-reported shyness at 4 years of age (Schmidt et al., 1997).

Kochanska, G., Coy, K. C., & Murray, K. T. (2001). The development of self regulation in the first four years of life. Child Development, 72, 1091-1111. Kagan, J., Reznick, J. S., & Gibbons, J. (1989). Inhibited and uninhibited types of children. Child Development, 60, 838-845. Schmidt, L. A., Fox, N. A., Rubin, K. H., Sternberg, E. M., Gold, P. W., Smith, C. C., et al. (1997). Behavioral and neuroendocrine responses in shy children. Developmental Psychobiology, 30, 127-140.

Approach to Attractive Objects

We measured children’s tendencies to approach attractive objects. The Experimenter brought in a gift bag and decorated toy box earlier in the visit (separately) and the latency for the child to approach these objects (looking at, touching) and positive affect was recorded and used as a measure of reactive impulsivity/approach to these objects. We measured approach to attractive objects with 30-month old toddlers, and data suggested that toddlers’ positive affect (but not physical approach) toward the “similar” dinky toys or gift bag was at least marginally negatively related to latency to touch the dinky toys and latency to touch the gift bag, r(206, 209) = -.16 and -.16, ps < .06 and .05, for dinky toys and gift bag, respectively (Spinrad et al., 2007).

Spinrad, T. L., Eisenberg, N., & Gaertner, B. M. (2007). Measures of effortful regulation for young children. Infant Mental Health Journal, 28, 606-626.

11