MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

Soft Power Bad

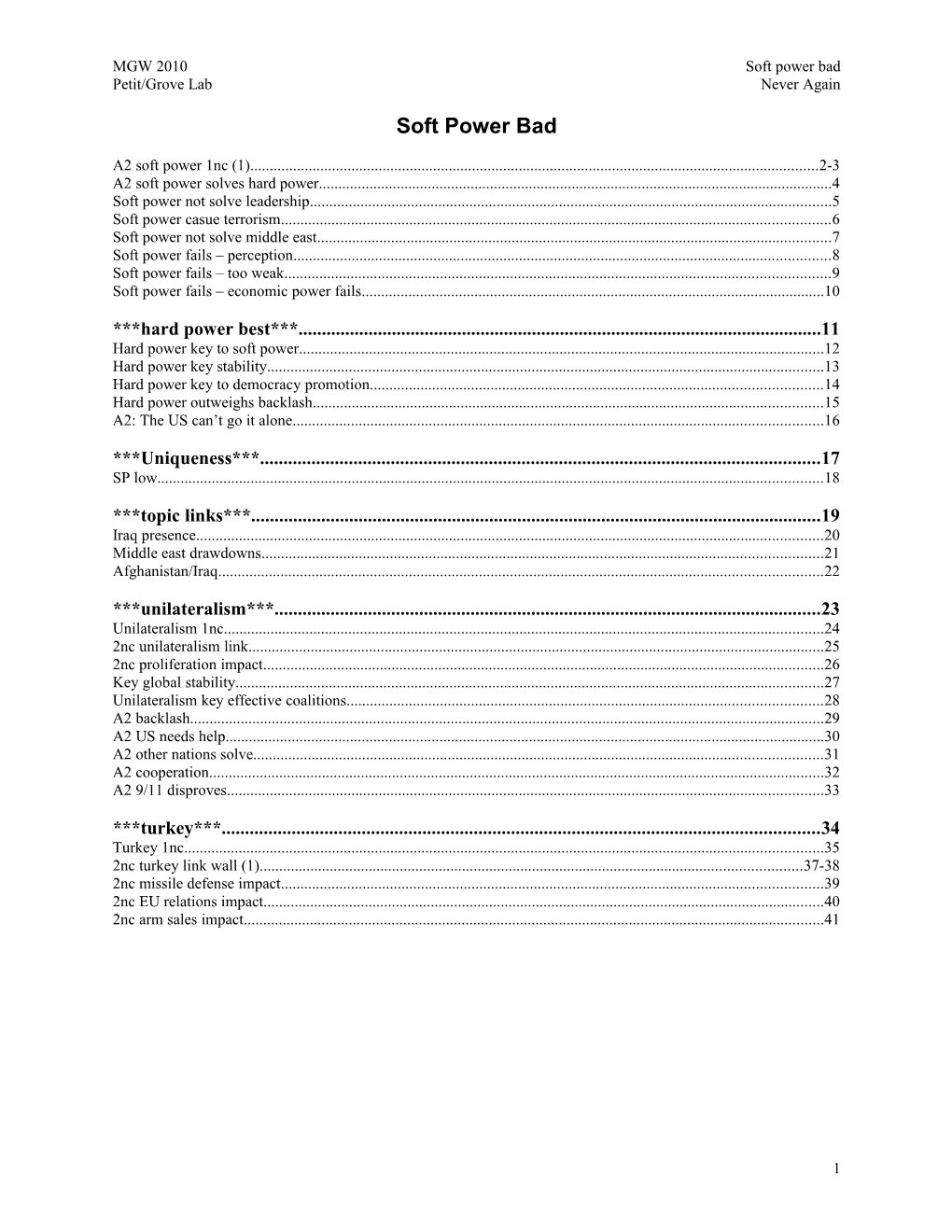

A2 soft power 1nc (1)...... 2-3 A2 soft power solves hard power...... 4 Soft power not solve leadership...... 5 Soft power casue terrorism...... 6 Soft power not solve middle east...... 7 Soft power fails – perception...... 8 Soft power fails – too weak...... 9 Soft power fails – economic power fails...... 10

***hard power best***...... 11 Hard power key to soft power...... 12 Hard power key stability...... 13 Hard power key to democracy promotion...... 14 Hard power outweighs backlash...... 15 A2: The US can’t go it alone...... 16

***Uniqueness***...... 17 SP low...... 18

***topic links***...... 19 Iraq presence...... 20 Middle east drawdowns...... 21 Afghanistan/Iraq...... 22

***unilateralism***...... 23 Unilateralism 1nc...... 24 2nc unilateralism link...... 25 2nc proliferation impact...... 26 Key global stability...... 27 Unilateralism key effective coalitions...... 28 A2 backlash...... 29 A2 US needs help...... 30 A2 other nations solve...... 31 A2 cooperation...... 32 A2 9/11 disproves...... 33

***turkey***...... 34 Turkey 1nc...... 35 2nc turkey link wall (1)...... 37-38 2nc missile defense impact...... 39 2nc EU relations impact...... 40 2nc arm sales impact...... 41

1 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

A2 soft power 1nc (1)

American soft power is unworkable – nations don’t believe in benevolent hegemony enough to overwhelm their resentment and fear*** Christopher Layne (Associate Professor in the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University) 2007 “American Empire: A Debate” p 68 Doubtless, American primacy has its dimension of benevolence, but a state as powerful as the United States can never be benevolent enough to offset the fear that other states have of its unchecked power. In international politics, benevolent hegemons are like unicorns—there is no such animal. Hegemons love themselves, but others mistrust and fear them—and for good reason. In today's world, others dread both the overconcentration of geopolitical weight in America's favor and the purposes for which it may be used. After all,"Nogreat power has a monopoly on virtue and, although some may have a greatdeal more virtue than others, virtue imposed on others is not seen as such bythem. All great powers are capable of exercising a measure of self-restraint, butthey are tempted not to and the choice to practice restraint is made easier by theexistence of countervailing power and the possibility of it being exercised."While Washington's self-proclaimed benevolence is inherently ephemeral, the hard fist of American power is tangible. Others must worry constantly that ifU.S. intentions change, bad things may happen to them. In a one-superpower world, the overconcentration of power in America's hands is an omnipresent challenge to other states's ecurity, and Washington's ability to reassure others of its benevolence is limited by the very enormity of its power.

Soft power is a myth. States won’t buy it – tangible power is all that matters, not intentions Christopher Layne, visiting fellow in foreign policy studies at Cato, Los Angeles Times, October 6, 2002 U.S. strategists believe that "it can't happen to us," because the United States is a different kind of hegemon, a benign hegemon that others will follow willin gly due to the attractiveness of its political values and culture. While flattering, this self-serving argument misses the basic point: Hegemons are threatening because they have too much power. And it is America's power--not the self-proclaimed benevolence of its intentions--that will shape others' response to it. A state's power is a hard, measurable reality, but its intentions, which can be peaceful one day but malevolent the next, are ephemeral. Hegemony's proponents claim that the United States can ino culate itself against a backlash by acting multilaterally. But other states are not going to be deceived by Washington's use of international institutions as a fig leaf to cloak its ambitions of dominance. And in any event, there are good reasons why the U.S. should not reflexively embrace multilateralism. When it comes to deciding when and how to defend American interests, Washington should want a free hand, not to have its hands tied by others.

Negative perception of American foreign policy overwhelms any cultural attraction. Zbigniew Brzezinski (Counselor at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and a professor of foreign policy @ Johns Hopkins) 2004 “The Choice: Global Domination or Global Leadership” p 186-8 Polls of worldwide public opinion suggest that virtual familiarity breeds affection for much of the American way of life even as it intensifies resentment of U.S. policies. Although such polls, because they reflect instant personal reactions to changing circumstances, are inherently volatile, certain patterns seem evident. A review of several polls' indicates that an overwhelming number of countries worldwide, including even France, China, and Japan (the major exceptions being Russia and the Middle East, followed to a lesser extent by Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh), view American popular culture favorably. At the same time, however, the spread of American "customs" is viewed predominantly as"bad" in a majority of countries (with even 50 per-cent of Britons reacting critically), the only major exception being Japan. Unlike American culture, American foreign policy is largely viewed negatively. Its perceived bias in favor of Israel against thePalestinians is frequently cited as the specific reason, as is America's perceived indifference to other countries' interests. Majorities in most countries believe that the United States is actually intensifying the gap between rich nations and poor ones. Thus the cultural impact of virtual familiarity with America collides with the political. The major political consequence of America's cultural seduction is that more is expected of America than of other states. To act selfishly in the name of "the national interest" is generally viewed as normal international behavior—yet America tends to beheld to a higher standard. In the aforementioned polls, those who were most dissatisfied with the state of their own countries tended to entertain a more jaundiced view of America, reinforcing the hypothesis that they expect more of America and hold it somehow accountable for the deplorable state of the world. This may partly be due to the highly self-righteous rhetoric of American political leaders, with its heavyreliance on idealistic and religious invocations. But the global publicopinion polls suggest that it is also a double-edged compliment bythose who truly expect more from America and resent its failure tomeet such elevated expectations when it comes to actual policy. Anti-Americanism bears the trappings of betrayed affection. America is thus admired and resented at the same time. Envy contributes to but is not the sole cause of the resentment. It stems from the sense that America's global reach affects almost everyone, especially those who have vicariously become an extension of America through virtual experience.They are captives of, and even more fre-quently willing participants in, the American mass-cultural sphere, but they feel that they are not heard in the American process of decision-making. The historic (American) slogan"No taxation without repre-sentation"finds its contemporary global equivalent in "NoAmericanization without representation." 2 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

A2 soft power 1nc (2)

Obama cannot just charm problems away – soft power cannot deal with almost every world threat Gieldon Rachman (Writer for the Financial Times) June 1 2009 “Obama and the limits of soft power,” Barack Obama is a soft power president. But the world keeps asking him hard power questions. From North Korea to Guantánamo Bay, from Iran to Afghanistan, Mr Obama is confronting a range of vexing issues that cannot be charmed out of existence. The problem is epitomised by the US president’s trip to the Middle East this week. Its focal point will be a much-trailed speech in Cairo on Thursday June 4, in which he will directly address the Muslim world. The Cairo speech is central to Mr Obama’s efforts to rebuild America’s global popularity and its ability to persuade – otherwise known as soft power. The president has been trying out potential themes for the speech on aides and advisers for months. He is likely to emphasise his respect for Islamic culture and history, and his personal links to the Muslim world. He will suggest to his audience that both the US and the Islamic world have, at times, misjudged and mistreated each other – and he will appeal for a new beginning. George W. Bush launched a military offensive in the Middle East. Mr Obama is launching a charm offensive. There is plenty to be said for this approach. Mr Bush embroiled America in a bloody war in Iraq that strengthened Iran and acted as a recruiting sergeant for America’s enemies. Mr Obama’s alternative strategy is based on diplomacy, engagement and empathy. Mr Bush had a shoe thrown at him in his last appearance in the Middle East. So if Mr Obama receives his customary standing ovation in Cairo, that will send a powerful symbolic message. But the president should not let the applause go to his head. Even if his speech is a success, the same foreign-policy problems will be sitting in his in-tray when he gets back to the Oval Office – and they will be just as dangerous as before.

Soft power cannot maintain U.S. hegemony – Britain circa 1930 has already proven this. Niall Ferguson (Herzog Professor of History at the Stern School of Business, New York University and a Senior Research Fellow of Jesus College, Oxford) 9/22/2003 “an empire in denial: the limits of US imperialism” Harvard International Review No. 3, Vol. 25; Pg. 64 One argument sometimes advanced to distinguish US "hegemony" from British Empire is qualitative. US power, it is argued, consists not just of military and economic power but also of "soft" power. According to Joseph Nye, "A country may obtain the outcomes it wants in world politics because other countries want to follow it, admiring its values, emulating its example, aspiring to its level of prosperity and openness." Soft power, in other words, is getting what you want without sticks or carrots. In the case of the United States, "it comes from being a shining 'city. upon a hill'"--an enticing New Jerusalem of economic and political liberty,. Nye is not so naive as to assume that the US way is inherently attractive to everyone, everywhere. But he does believe that making it attractive matters more than ever before because of the global spread of information technology. To put it simply, soft power can reach the parts of the world that hard pouter cannot. But does this really make US power so very different from imperial power? On the contrary. If anything, it illustrates how very like the last Anglophone empire the United States has become. The British Empire, too, sought to make its values attractive to others, though initially the job had to he done by "men on the spot." British missionaries, businessmen, administrators, and schoolmasters fanned out across the globe to "entice and attract" people toward British values. These foot- slogging efforts were eventually reinforced by technology. It was the advent of wireless radio--and specifically the creation of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC)--which really ushered in the age of soft power in Nye's sense of the term. Within six years, the BBC had launched its first foreign language service--in Arabic, significantly--and, by the end of 1938, it was broadcasting around the world in all the major languages of continental Europe. In some ways, the soft power that Britain could exert in the 1930s was greater than the soft power of the United States today. In a world of newspapers, radio receivers, and cinemas--where the number of content- supplying corporations (often national monopolies) was relatively small--the overseas broadcasts of the BBC could hope to reach a relatively large number of foreign ears. Yet whatever soft power Britain thereby wielded did nothing to halt the precipitous decline of British power after the 1930s. This raises the question of how much US soft power really matters today. If the term is to denote anything more than cultural background music to more traditional forms of dominance, it surely needs to be demonstrated that the United States can secure what it wants from other countries without coercing or suborning them, but purely because its cultural exports are seductive. One reason for skepticism about the extent of US soft power today is the very nature of the channels of communication for US culture, the various electronic media through which US culture is currently transmitted tend to run from the United States to Western Europe, Japan, and in the case of television, Latin America. It would be too much to conclude that US soft power is abundant where it is least needed, for it may well he that a high level of exposure to US cinema and television is one of the reasons why Western Europe,Japan, and Latin America are on the whole less hostile to the United States than countries in the Middle East and Asia. But the fact remains that the range of US soft power in Nye's sense is more limited than is generally assumed.

3 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

A2 soft power solves hard power

Soft power cannot maintain U.S. hegemony – Britain circa 1930 has already proven this. Niall Ferguson (Herzog Professor of History at the Stern School of Business, New York University and a Senior Research Fellow of Jesus College, Oxford) 9/22/2003 “an empire in denial: the limits of US imperialism” Harvard International Review No. 3, Vol. 25; Pg. 64 One argument sometimes advanced to distinguish US "hegemony" from British Empire is qualitative. US power, it is argued, consists not just of military and economic power but also of "soft" power. According to Joseph Nye, "A country may obtain the outcomes it wants in world politics because other countries want to follow it, admiring its values, emulating its example, aspiring to its level of prosperity and openness." Soft power, in other words, is getting what you want without sticks or carrots. In the case of the United States, "it comes from being a shining 'city. upon a hill'"--an enticing New Jerusalem of economic and political liberty,. Nye is not so naive as to assume that the US way is inherently attractive to everyone, everywhere. But he does believe that making it attractive matters more than ever before because of the global spread of information technology. To put it simply, soft power can reach the parts of the world that hard pouter cannot. But does this really make US power so very different from imperial power? On the contrary. If anything, it illustrates how very like the last Anglophone empire the United States has become. The British Empire, too, sought to make its values attractive to others, though initially the job had to he done by "men on the spot." British missionaries, businessmen, administrators, and schoolmasters fanned out across the globe to "entice and attract" people toward British values. These foot- slogging efforts were eventually reinforced by technology. It was the advent of wireless radio--and specifically the creation of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC)--which really ushered in the age of soft power in Nye's sense of the term. Within six years, the BBC had launched its first foreign language service--in Arabic, significantly--and, by the end of 1938, it was broadcasting around the world in all the major languages of continental Europe. In some ways, the soft power that Britain could exert in the 1930s was greater than the soft power of the United States today. In a world of newspapers, radio receivers, and cinemas--where the number of content- supplying corporations (often national monopolies) was relatively small--the overseas broadcasts of the BBC could hope to reach a relatively large number of foreign ears. Yet whatever soft power Britain thereby wielded did nothing to halt the precipitous decline of British power after the 1930s. This raises the question of how much US soft power really matters today. If the term is to denote anything more than cultural background music to more traditional forms of dominance, it surely needs to be demonstrated that the United States can secure what it wants from other countries without coercing or suborning them, but purely because its cultural exports are seductive. One reason for skepticism about the extent of US soft power today is the very nature of the channels of communication for US culture, the various electronic media through which US culture is currently transmitted tend to run from the United States to Western Europe, Japan, and in the case of television, Latin America. It would be too much to conclude that US soft power is abundant where it is least needed, for it may well he that a high level of exposure to US cinema and television is one of the reasons why Western Europe,Japan, and Latin America are on the whole less hostile to the United States than countries in the Middle East and Asia. But the fact remains that the range of US soft power in Nye's sense is more limited than is generally assumed.

Soft power cannot prevent war Fen Hampsen et al, 1998 International Journal Perhaps the two best examples of the continued utility of military force are the Persian Gulf conflict of 1990-1 and the coalition deployment to the same region, led by the United States (and supported by the United Nations), in early 1998 to ensure Iraq's compliance with the 1991 ceasefire agreement. Both missions have occasioned much debate in the scholarly community, and deservedly so, but we take it as axiomatic that for both sides on each occasion the role of military force was critical in the evolution -- and resolution -- of the crisis. In 1990-1, this would appear to be self-evident, while in 1998 no less a commentator than Kofi Annan, in the wake of Iraq's decision to again permit weapons inspectors access to its presidential palaces, dubbed the United States and Britain 'the perfect UN peacekeepers' for their show of force in support of UNSCOM. It is important to note that in each case soft power proved singularly unable to affect the actions of a single, isolated, pariah state, albeit one that possessed considerable military wherewithal and a modicum of regional legitimacy. It is certainly dangerous to generalize from the Iraqi example, but one might at least question the applicability of soft power to powerful rogue states in bold defiance of international law and international agreements.

4 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

Soft power not solve leadership

Legitimacy is irrelevant to leadership Robert Kagan (senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace) Jan 15 2006 The Washington Post This does not mean the United States has not suffered a relative decline in that intangible but important commodity: legitimacy. A combination of shifting geopolitical realities, difficult circumstances and some inept policy has certainly damaged America's standing in the world. Yet, despite everything, the American position in the world has not deteriorated as much as people think. America still "stands alone as the world's indispensable nation," as Clinton so humbly put it in 1997. It can resume an effective leadership role in the world in fairly short order, even during the present administration and certainly after the 2008 election, regardless of which party wins. That is a good thing, because given the growing dangers in the world, the intelligent and effective exercise of America's benevolent global hegemony is as important as ever.

Soft power cannot prevent war Fen Hampsen et al, 1998 International Journal Perhaps the two best examples of the continued utility of military force are the Persian Gulf conflict of 1990-1 and the coalition deployment to the same region, led by the United States (and supported by the United Nations), in early 1998 to ensure Iraq's compliance with the 1991 ceasefire agreement. Both missions have occasioned much debate in the scholarly community, and deservedly so, but we take it as axiomatic that for both sides on each occasion the role of military force was critical in the evolution -- and resolution -- of the crisis. In 1990-1, this would appear to be self-evident, while in 1998 no less a commentator than Kofi Annan, in the wake of Iraq's decision to again permit weapons inspectors access to its presidential palaces, dubbed the United States and Britain 'the perfect UN peacekeepers' for their show of force in support of UNSCOM. It is important to note that in each case soft power proved singularly unable to affect the actions of a single, isolated, pariah state, albeit one that possessed considerable military wherewithal and a modicum of regional legitimacy. It is certainly dangerous to generalize from the Iraqi example, but one might at least question the applicability of soft power to powerful rogue states in bold defiance of international law and international agreements.

Only a risk of backlash Majie (Senior Research Fellow, Vice President of Shanghai Institute for International Strategic Studies) May 6 2002 “Role of Soft Power in International Relations” Soft power is the first choice in handling international relations. Joseph Nye analyzed the role of soft power in his Bound to Lead. He held that, in international politics, a country can carry out its expectations just because other countries would take it as an example or accept a system conducive to such results. In this sense, it is same important in international politics to make directions, to establish environment, and to stimulate reforms in other countries. Nye called this power as co-optive power. He believes, if a country’s ideology and culture are attractive, others would like to imitate and follow. At present, the United States has traditional hard power stronger than any other country. And it also has resources of soft power in ideology and institution that can assure itself to keep the leadership in the new field of interdependence.[6] Just from this strategic perspective, Nye pointed out that the United States should enhance the co-optive power of its culture and attraction of its lifestyle to make it become preponderant not only in hard power but also in soft power, thus establishing its ideological domination in the whole world. It is apparent that soft power plays a strong reactive role for a country in the area of international politics. Its positive impacts can help a country make feasible national strategy, guide national enthusiasm, shape united will and strong cultural power, and therefore promote the development of comprehensive national power, improve the country’s international status, and increase its international contribution and influence. Nonetheless, on the contrary, if the national strategy was infeasible, even sightless or dangerous, the soft power would misguide people and play a negative role, leading to national enthusiasm lost, will frustrated, and hard national power reduced. Its damage would be incalculable . The international status and competitiveness of such a country would decrease dramatically till nothing . Any country, when making its national strategy, must pay attention to creating better surroundings, making its development model, values, lifestyle and corresponding systems attractive, appealing, and inspiring, and incorporating both tangible and intangible powers in order to assure the achievement of national interests. Therefore, soft power is always the first option of tool for countries to deal with various affairs in contemporary international relations.

5 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

Soft power casue terrorism

US soft power increases terrorist aggression John Matalin (CNN Commentator) 2009 “Matalin: Obama’s ’soft power’ makes us weak”, CNN's American Morning John Roberts: The former vice president has said several times that the Obama administration’s policies are making America less safe. Where’s the evidence for that? Mary Matalin: Common sense and history… It’s one thing to say all of the things Obama said on the campaign trail but within hours of being the actual commander in chief, he was suggesting the previous seven years marked by no attacks were policies that were ineffective, were immoral, were illegal. That broadcast to our enemies a weakness. Weakness invites provocation. Secondly, as he was clear in his speech yesterday, he wants to return to a 9/10 law enforcement policy rather than a prevention policy. Three, the threshold and key tool for fighting this enemy is gathering intelligence. And he’s clearly demoralized and undermined those intelligence gatherers. Four, Gitmo, releasing the hardest of the hardened terrorists into some system, whatever system that might be, either would divulge classified material… if they put them in the prison population, they can hatch plots as was the case in New York. So I could go on and on. But some of these policies, by virtue of the former vice president speaking out, were stopped as in the release of the detainee photos. Roberts: But is there any empirical evidence that America is less safe today? Has anything happened around the world to suggest that we are less safe? There are many people who believe that this administration’s policy of engagement, in fact, will make this country more safe. Matalin: Well there’s no evidence of that either. In fact there’s evidence to the contrary. This so-called “soft power” has resulted in Iran being more verbose, launching a missile this week. North Korea’s pulled out of any negotiating posture. Soft power isn’t working. There’s no evidence for that. And there’s plenty of evidence to the contrary that weakness invites provocation. During the ’90s, when we did not respond to six attacks in six years, the ranks of al Qaeda swelled by some 20,000. That was the recruitment tool. Weakness and successful attacks is the recruitment tool. Roberts: Just to go back to what you said about Iran and North Korea — both of those countries did exactly the same thing during the Bush administration. Matalin: This supposedly “let’s sit down and talk,” was supposed to make them come to the table and talk. In fact, they’ve gotten more aggressive. So, he’s doing what he said he would do, which would render them putty in his hands as he thinks is the case as sometimes appears to be the case in America in his own party. That’s not what’s happening. That’s not real politics. So he’s been in there a couple of 16 weeks, three months, whatever it’s been. But if he were allowed to pursue un-debated, these sorts of policies that he’s put on the table and heretofore, they have been un-debated, it’s been a one-sided argument, there’s no doubt, and history shows and common sense would dictate that we would be a less safe country than we were for the past seven or eight years. Roberts: The president said yesterday he believes America is less safe because of the very existence of Guantanamo Bay, that it’s probably created more terrorists worldwide than it’s ever detained. Do you agree with that statement? Because the Bush administration, President Bush said he would like to close Guantanamo and just has to figure out how to do it. Matalin: Yeah, John, I’ll go to your construct. He offered no evidence for that. And it’s a tautological argument, as I just noted. The ranks of al Qaeda were absolutely exponentially swollen during the ’90s when we did not respond… This enemy existed way before Guantanamo. It makes no sense to say that fighting the terrorists makes the terrorist. That’s a tautological argument. Yes, President Bush wanted to close it. Some of us disagreed with that. For the very reasons we’re disagreeing with President Obama right now.vWhat are you going to do with these detainees? Even the ones that have been released, which were supposed to be the ones that could have been released, the D.O.D. and some suspect this is an under-estimate – one out of seven go back to the battlefield. The top operatives in Yemen, which is the new hot grounds, the top operatives in Waziristan, were released from Gitmo. It’s not good to close it down or release these into our population, certainly, or any population.

6 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

Soft power not solve middle east

Obama’s soft power cannot solve Middle Eastern conflict Giedon Rachman (Writer for the Financial Times) June 1 2009 “Obama and the limits of soft power,” In particular, there is chatter in official Washington that the Israelis may be gearing up to attack Iran’s nuclear facilities before the end of the year. The Obama administration is against any such move and it is normally assumed that Israel would not dare to pull the trigger without the go-ahead from Washington – not least because the Israelis would have to fly across US-controlled airspace to get to their targets. But the Americans do not have a complete veto over Israel’s actions. One senior US official asks rhetorically: “What are we going to do? Shoot down their planes?” A conflict between Israel and Iran would scatter the Obama administration’s carefully laid plans for Middle East peace to the winds. It would also make talk of improving American soft power around the world seem beside the point. The immediate task would be to prevent a wider regional war. In the meantime, the US will press on with the effort to achieve peace between the Israelis and the Palestinians. But even that goal is unlikely to be advanced much by Mr Obama’s trip to the Middle East. Many in the audience in Cairo and in the wider Islamic world will want and even expect the new president to lay out a complete vision for a peace settlement and to apply unambiguous pressure on Israel. For reasons of domestic politics, diplomacy and timing, Mr Obama is highly unlikely to do this. Yet while his Arab audience may be disappointed by what he has to say about the Middle East peace process, Mr Obama is already facing an increasingly tense relationship with the new Israeli government. The administration has now clashed openly with the Israelis over the Netanyahu government’s tolerance of expanded settlements in occupied Palestinian land. Mr Obama is also running up against the limits of soft power elsewhere. Closing the prison camp at Guantánamo was meant to be the ultimate tribute to soft power over hard power. The Obama team argued consistently that the damage that Guantánamo did to America’s image in the world outweighed any security gains from holding al-Qaeda prisoners there. Yet, faced with the backlash against releasing the remaining 240 prisoners or imprisoning them in the US, the Obama administration has back-tracked. It is not clear whether Guantánamo will be closed on schedule or what will happen to the riskier-sounding prisoners, who may still be held indefinitely. The much-criticised military trials are likely to be revived. In Afghanistan, Mr Obama is trying a mixture of hard and soft power. There will be a military surge – but also a “civilian surge”, designed to build up civil society and governance in Afghanistan. Old hands in Washington are beginning to shake their heads and mutter about Vietnam.

7 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

Soft power fails – perception

Soft power is useless – hard power overwhelms Journal of Commerce, October 20, 1998 Under the government of Prime Minister Jean Chretien, Canada's international reputation has been dilettantish and irrelevant. In particular, the fondness of Foreign Affairs Minister Lloyd Axworthy for his notion that, in the post- Cold War world, costly ""hard-power'' resources, such as an army, are of lesser importance than "" soft-power' ' persuasion have been scorned as naive. Mr. Axworthy favors ""getting others to want what you want'' through "" peacebuilding'' and ""constructive engagement.'' ""In the real world, whether Mr. Axworthy will admit it or not, hard power does a better job of protecting Canada's interests when others refuse to want what we want,'' says Kim Richard Nossal, one of Canada's pre-eminent political scientists. Similarly, Nobel Peace Prize-winner Jose Ramos Horta has dismissed Canada's foreign policy as ""wishy-washy'' and ""bankrupt.'' A policy of ""constructive engagement,'' he says, is merely a smokescreen to justify trading with repressive regimes. But perhaps the harshest criticism has come from British Lt. Gen. Sir Hew Pike, a NATO commander in Bosnia, who declared that the Canadian military had ""surrendered any claim to be a war-fighting force.'' There is some justice in the claim. When NATO asked members in July to contribute fighter planes for possible attacks against Serbian forces, Canada conveniently didn't have any aircraft available. Likewise, the Canadian government offered only token support for a show of force against Iraq earlier this year. Such behavior - ""defense lite,'' as one analyst puts it - does not win Canada much respect. In Bosnia in 1994, Canada's objections to NATO air strikes were ignored by both the Americans and the British, who thought the country's meager troop contribution didn't warrant it a hearing. All in all, Canada's soft-power policies are little more than foreign policy on the cheap. Soft power is effective only when it's backed up by a country's willingness ""t o commit its treasure to world affairs,'' as Mr. Nossal puts it. And that means, in part, spending to have a credible military force.

Hard power trumps Michael Hirsh, former Foreign Editor of Newsweek, Foreign Affairs, September/October, 2002 The hegemonists are right about one thing: hard power is necessary to break the back of radical Islamic groups and to force the Islamic world into fundamental change. Bin Laden said it well himself: "When people see a strong horse and a weak horse, by nature they wil l like a strong horse." The United States must be seen as the strong horse. The reluctant U.S. interventionism of the 1990s made no headway against this implacable enemy. Clinton's policy of offering his and NATO's credibility to save Muslims in Bosnia and Kosovo won Washington little goodwill in the Islamic world.

8 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

Soft power fails – too weak

9-11 proves soft power is too weak to avert problems Richard Betts, Professor and director of the Institute of War and Peace Studies at Columbia,Political Science, March 22, 2002 Kamikaze hijacking also reflects an impressive capacity for strategic judo, the turning of the West's strength against itself. (12) The flip-side of a primacy that diffuses its power throughout the world is that advanced elements of that pow er become more accessible to its enemies. Nineteen men from technologically backward societies did not have to rely on home-grown instruments to devastate the Pentagon and World Trade Center. They used computers and modern financial procedures with facility, and they forcibly appropriated the aviation technology of the West and used it as a weapon. They not only rebelled against the " soft power" of the United States, they trumped it by hijacking the country's hard power. (13) They also exploited the charac teristics of U.S. society associated with soft power --the liberalism, openness, and respect for privacy that allowed them to go freely about the business of preparing the attacks without observation by the state security apparatus. When soft power met the clash of civiliz ations, it proved too soft.

Soft power fails – only military force matters Fen Hampson and Dean Oliver, International Journal, June, 1998 United Nations peacekeepers in Bosnia were repeatedly handcuffed by rules of engagement that generally prohibited the use of force against local warlords and by a pitiful weapons suite that would have rendered such bravado suicidal in any case. Perhaps the two best examples of the continued utility of military force are the Persian Gulf conflict of 1990-1 and the coalition deployment to the same region, led by the United States (and supported by the United Nations), in early 1998 to ensure Iraq's compliance with the 1991 ceasefire agreement. Both missions have occasioned much debate in the scholarly community, and deservedly so, but we take it as axiomatic that for both sides on each occasion the role of military force was critical in the evolution -- and resolution -- of the crisis. In 1990-1, this would appear to be self-evident, while in 1998 no less a commentator than Kofi Annan, in the wake of Iraq's decision to again permit weapons inspectors access to its presidential palaces, dubbed the United States and Britain 'the perfect UN peacekeepers' for their show of force in support of UNSCOM. It is important to note that in each case soft power proved singularly unable to affect the actions of a single, isolated, pariah state, albeit one that possessed considerable military wherewithal and a modicum of regional legitimacy. It is certainly dangerous to generalize from the Iraqi example, but one might at least question the applicability of soft power to powerful rogue states in bold defiance of international law and international agreements.

9 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

Soft power fails – economic power fails

Economic leverage does not stop war – nuclear deterrence is key Joseph Nye, assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs, Washington Quarterly, Winter, 1996 Just as important as these changes in the distribution of power are changes in the nature of power and the processes through which it can be exercised. Some Liberals argue that economic power has replaced military power as the central medium of international politics, but this is greatly overstated. Realists rightly argue that economic instruments still cannot compare with military forces in their coercive and deterrent effects. Economic sanctions, for example, did not compel the Iraqis to withdraw from Kuwait. In addition, all it takes is one good security crisis to send stock and commodity markets spinning, set off capital flight, stifle investment, and raise the risk premium on the full range of economic transactions. Economic instruments have grown slightly in importance relative to military ones, but this was already true by the 1970s. The main change has been in the fungibility of military power itself. Nuclear weapons have so greatly raised the potential costs of conflict that the great power states that have them have worked hard to prevent any direct military conflicts among themselves, including conventional conflicts that could escalate to the nuclear level.

Hard power outweighs soft power Robert Spulak, senior analyst at the Strategic Studies Center, “The Case in Favor of US Nuclear Weapons,” Parameters, Spring 1997, http://carlisle-www.army.mil/usawc/Parameters/97spring/spulak.htm, accessed 10/18/02 Some argue that economic strength alone can confer superpower status because economic powers can use trade and economic policies to promote their economic welfare.[12] However, economic power is only one contributor to a nation's overall power. The highest priorities of the United States government are to protect our central security interests. Economic power alone cannot guarantee security; in fact, greater economic interests may extend the boundaries of our security interests, thereby increasing our vulnerability to coercion or adding new opportunities for others to try to influence US foreign policy. The greatest contribution of economic power to security is that economic resources allow for the fielding of a formidable military force. This is why there is a great deal of concern over China's economic growth: not primarily because of China's future ability to trade effectively (although this also may be of great concern), but because of its rapid growth in military spending and the enormous resources potentially available for its military. Even states that could not compete economically have been superpowers (e.g., the Soviet Union). The possession of a robust nuclear arsenal confers real diplomatic advantages on the United States. I t is a vital symbol and part of the substance of our world leadership. Diplomacy is always performed against the backdrop of military capability. In addition, nuclear weapons, and the threats they imply, can be used explicitly (although not without risk) to protect US interests.[13] For example, during the superpower confrontation caused by the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, increased US alert status, including nuclear forces, and hints of "incalculable consequences" probably helped to deter Soviet intervention in Egypt. (Soviet nuclear capabilities also may have helped to motivate the United States to work to prevent the destruction of the encircled Egyptian Third Army.) There has been widespread speculation that allusions to nuclear use may have deterred Iraq from using chemical weapons in the 1990-91 Gulf War. And, the US carefully refrained for several days from ruling out a nuclear strike against a Libyan underground chemical weapons facility to increase the diplomatic pressure to stop construction.

10 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

***hard power best***

11 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

Hard power key to soft power

Soft power is impossible without strong military power Josef Joffe, German journalist, Conversations with History, “Power and Culture in International Affairs,” January 20 and March 23, 2000, http://globetrotter.berkeley.edu/people/Joffe/joffe-con4.html, accessed 10/15/02 I think power has to be seen like a bundle of currencies. Traditionally the most important currency of power was military power, strategic power. Machiavelli said it's easier to get gold with good soldiers than to get good soldiers with gold. So on top, the most fungible of all currency is strategic. Then you can go down to all kinds of other "currencies": economic power, the attraction of your political and social system, even of your movies and your TV, your diplomatic skills. Or the power radiating from ideas: part of the great power that the Soviet Union had for a while was that this idea of socialism was a very powerful, attractive idea which inspired the entire Third World after decolonization. Everybody wanted a kind a Marxist-Soviet model of economic development and one- party states. So in the Berlin-Berkeley Belt, where the strategic issue for the time being does not arise, those who have the most soft power sources will do very well, such as Germany. But also the United States. Yes. But the most important thing is, the best deal you can get is when hard power and soft power come together. The Vatican has a lot of soft power but it has no hard power and so that means the influence of the Vatican is limited. Switzerland has a lot of soft power but nothing in the hard power field. So if you really want to sit pretty today you have to be like the United States, because the United States has all of these resources in spades. It's the mightiest military power in the world, it is the mightiest economy.

12 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

Hard power key stability

Military power is the crucial factor for securing peace David Talbot, Salon.com, January 3, 2002 From the Gulf War on, the hawks have been on the right side in all the major debates about U.S. intervention in the world's troubles. The application of American military power -- to drive back Saddam Hussein's invasion of Kuwait, stop Slobodan Milosevic's genocidal campaigns in the Balkans, and destroy the terrorist occupation of Afghanistan -- has not just protected U.S. interests, it has demonstrably made the world safer and more civilized. Because of the U.S.-led allied victory in the Persian Gulf, Saddam -- the most blood-stained and dangerous dictator in power today -- was blocked from completing a nuclear bomb, taking control of 60 percent of the world's oil resources and using his fearsome arsenal (including biological and chemical weapons) to consolidate Iraq's position as the Middle East's reigning force. Because of the U.S.-led air war against Milosevic, the most ruthless "ethnic cleansing" program since the Holocaust was finally thwarted -- first in Bosnia and then in Kosovo -- and the repulsive tyrant is now behind bars in the Hague. And in Afghanistan, the apocalyptic master plan of the al-Qaida terror network was shattered by America's devastatingly accurate bombing campaign, along with the medieval theocracy that had thrown a cloak of darkness over the country. These demonstrations of America's awesome firepower were clearly on the right side of history. In fact, the country's greatest foreign policy disasters during this period occurred because the U.S. government failed to assert its power: when President George H. W. Bush aborted Operation Desert Storm before it could reach Baghdad and finish off Saddam (whose army had only two weeks of bullets left) and when he failed to draw a line against Milosevic's bloody plans for a greater Serbia; and when President Bill Clinton looked the other way while a genocidal rampage took the lives of a million people in Rwanda and when he failed to fully mobilize the country against terrorism after the 1993 World Trade Center bombing and the later attacks on American targets abroad -- a failure that extended through the first eight months of Bush II.

13 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

Hard power key to democracy promotion

Hard power is key to democracy promotion Michael McFaul, research fellow at the Hoover Institution and an associate professor of political science at Stanford, Policy Review, April 2002 TO EFFECTIVELY PROMOTE liberty abroad over the long haul, the United States must maintain its overwhelming military advantage over the rest of the world. American hegemonic power deters other great powers in the international system from balancing against the United States. Massive military might offers incentives for less powerful countries to cooperate with the United States. The ability to defeat anti-democratic enemies decisively, quickly, and with minimum loss of life for American armed forces -- Hussein in Iraq, Milosevic in Serbia, and the Taliban in Afghanistan -- offers a powerful argument for the benefits of friendly relations with the United States. If American leaders begin to make internal liberalization a condition of friendly relations with the United States, then sustaining unipolarity helps to promote democracy abroad. Maintaining American economic prowess is also necessary. In addition to maintaining American power, U.S. foreign policymakers must develop policies and military doctrines that can deploy this power to effect regime change. The United States should try to avoid the export of revolution through the barrel of the gun. Yet the United States must have the fortitude, plans, and means available to assist the overthrow of anti-democratic regimes. On rare occasions, discussed below, these resources have to be used. Nevertheless, the mere presence of such resources will help to make American threats about deploying them look more credible. The quick defeat of both Milosevic and the Taliban -- predicted by few at the beginning of these campaigns -- has demonstrated once again that the American armed forces are second to none. Decades of sustained investment in military training, technologies, and personnel have paid off. Yet U.S. armed forces need to continue to retool and reorganize for dealing with the new security challenges of the post-Gold War era. The tens of thousands of U.S. soldiers stationed in Germany waiting to repel a Soviet tank offensive need new missions. Fat budgets cannot be an excuse for avoiding reform.

Soft power can’t spur democratization and peace. Only hard power prevents conflict Charles Lane, Weekly Standard, January 17, 2000 Thanks to American power, then, fascism and communism have been mostly vanquished. The remaining task is to remove them where they linger (China, North Korea, Cuba, Iraq, Serbia), and to cope with or over-come other ideologically based obstacles to democracy -- like Islamic fundamentalism, the "Asian values" canard, and the tribal and ethnic strife that bedevil the Arab world, sub-Saharan Africa, the Caucasus, and the Balkans. It may take more than a century to handle all of this unfinished business. But, if the United States is serious about defending and consolidating democracy, it will have to identify democracy's enemies and oppose them, both with the force of our ideas and, where necessary, with just plain force. In short, what Joseph Nye has called " soft power" -- foreign aid, trade, and the other persuasive tools which Carothers and Diamond emphasize -- may not be enough. "Hard power," the maintenance of a strong U.S. military and a network of global security commitments and alliances capable of protecting democracies and resisting aggressive dictatorships, will surely continue to play an indispensable role. Doubters need only ask themselves whether democracy in Taiwan, South Korea, or even Japan would be stabilized or destabilized by a U.S. pullout from East Asia -- where China increasingly flexes its military muscles. Diamond and Carothers both make eloquent arguments that the United States can help consolidate emerging democracies by better fulfilling its exemplary role: by cleaning up its own democratic act at home. The "demonstration effect" of successful, stable self-government in America, they reason, has proved powerful in the past. So it should prove powerful in the future, as well: The more we do to root out domestic ills like police brutality and crooked campaign financing, the more credibility we will confer on democrats abroad who urge their fellow citizens to emulate us. Let us never stop trying to perfect our own politics, whose example surely has helped inspire would-be democrats across the globe. Just the same, there are reasons to remain skeptical about how much this particular demonstration effect can accomplish. One is historical: The world's most recent wave of democratization began in the mid-1970s, at a time when America was just emerging from Vietnam, Watergate, and segregation -- and just about to enter a period of brutal stagflation. To a great many people at home and abroad, it appeared that American democracy was altogether too rotten to compete with the Soviet Union. A whole Third World generation gravitated to radical and revolutionary doctrines as a result. But still the democrats of Portugal, Spain, and Greece -- and later, of Latin America and much of Asia -- carried the day. How America looked from a distance was, ultimately, a secondary issue. The example of democratizing neighboring states surely weighed heavier. What's more, any demonstration effect is inherently subjective. Is America's system of campaign finance really a symptom of political rot, as Diamond and Carothers seem to believe so strongly? Or is it simply the result of an irreconcilable conflict between equally valid democratic ideals: a maximal amount of free (and expensive) political speech, on the one hand, and a level political playing field of unimpeachable integrity, on the other? Voters, legislatures, and courts have been wrestling with this question for twenty-five years and haven't managed to settle it. The bottom line is that no matter how good an example we set, and no matter how genuine the reforms we adopt, anti-democratic forces will always find reasons to condemn us and, by extension, democracy itself.

14 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

Hard power outweighs backlash

Overwhelming military force ensures compliance, even if countries are upset Immanuel Wallerstein, senior research scholar at Yale, Foreign Policy, July 1, 2002 Following the terrorist attacks, Bush changed course, declaring war on terrorism, assuring the American people that "the outcome is certain" and informing the world that "you are either with us or against us." Long frustrated by even the most conservative U.S. administrations, the hawks finally came to dominate American policy. Their position is clear: The United States wields overwhelming military power, and even though countless foreign leaders consider it unwise for Washington to flex its military muscles, these same leaders cannot and will not do anything if the United States simply imposes its will on the rest. The hawks believe the United States should act as an imperial power for two reasons: First, the United States can get away with it. And second, if Washington doesn't exert its force, the United States will become increasingly marginalized. Today, this hawkish position has three expressions: the military assault in Afghanistan, the de facto support for the Israeli attempt to liquidate the Palestinian Authority, and the invasion of Iraq, which is reportedly in the military preparation stage. Less than one year after the September 2001 terrorist attacks, it is perhaps too early to assess what such strategies will accomplish. Thus far, these schemes have led to the overthrow of the Taliban in Afghanistan (without the complete dismantling of al Qaeda or the capture of its top leadership); enormous destruction in Palestine (without rendering Palestinian leader Yasir Arafat "irrelevant," as Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon said he is); and heavy opposition from U.S. allies in Europe and the Middle East to plans for an invasion of Iraq. The hawks' reading of recent events emphasizes that opposition to U.S. actions, while serious, has remained largely verbal. Neither Western Europe nor Russia nor China nor Saudi Arabia has seemed ready to break ties in serious ways with the United States. In other words, hawks believe, Washington has indeed gotten away with it.

Hard power overwhelms anger Antony Blinken, senior fellow at CSIS and former member of the National Security Council, Washington Quarterly, Spring, 2002 Why should the United States care that some criticize its policies and others resent its power? Following U.S. military success in Afghanistan, concluding that unilateral might makes right, silencing critics and creating a bandwagon effect among friends, is tempting. As Charles Krauthammer wrote, "We made it plain that even if no one followed us, we would go it alone. Surprise: others followed. . . . Not because they love us. Not because we have embraced multilateralism. But because we have demonstrated astonishing military power and the will to defend vital American interests, unilaterally if necessary." Military power remains the foundation of U.S. security; successfully applied, it magnifies U.S. influence.

15 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

A2: The US can’t go it alone

Their evidence asserts that allies are necessary but doesn’t say what they’re necessary for. The US has overwhelming military capabilities and economic resources and is willing to leverage those to enforce its will. Name a problem that we need France on our side to deal with.

The US can go it alone. Cooperation is a luxury, not a necessity John Gibson, Fox News Network, August 14, 2002 An eye-popping piece in the "USA Today," it says that the America- hating craze of the Middle East has now fully morphed itself into the face of the average European and most frightfully morphed into the average Brit, our most stalwart of overseas supporters. And it isn't just editorial writers, says "USA Today," it's everyday citizens who launch into tirades against Americans they bump into on the street or in the office. Why? Because America, the world now realizes, is so big and so strong it can do whatever it likes and no one can stop America. America doesn't need help for a war and if America doesn't like the Kyoto Treaty or the International Criminal Court, America will simply walk away. It can and it will. So this has all the Lilliputians screaming bloody murder. How dare you be so big? How dare you not listen to us? How dare you not need us? That sound you hear is the frustrated stamping of tiny little feet. I say Lilliputians because the whole thing has got me thinking about Gulliver, who wandered the world in Jonathan Swift's mind and eventually met a civilization of teeny little people who tried to tie him down with their twine. All the Lilliputians will think I'm being prototypically American, arrogant, because I've drawn this very allusion, the American giant and the rest of the world, Lilliputians. But the Lilliputians put themselves in this position by telling us we need their permission to do anything, especially to defend ourselves from the very terrorists who hide among them in their liberal, forgiving, tolerant, and ultimately blind society. The Brits, for example, tolerate in their midst the most hateful and vicious of Islamic radicals who plan and scheme against America with the protection of the British government. The Lilliputians also don't like creeping American culture, the fast food joints and the music and the movies. OK. So does that mean the Lilliputians find all that junk so enticing they simply cannot resist? Mostly, the Lilliputians don't want us to be able to defend ourselves without their permission or help. They resent it, oh, so much that we, the world's only Gulliver, can stomp Saddam Hussein if we decide we need to and either the Lilliputians will have to side with us or they'll stand around clucking their tongues and stamping their little feet. It's tough being Gulliver. It's pitiful to be a Lilliputian. They should grow up.

16 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

***Uniqueness***

17 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

SP low

U.S. soft power is one the decline the E.U. has taken the position of the world’s financial capital again The New American Foundation 08 Parag Khanna, author of The Second World: Empires and Influence in the New Global Order2007 he was a senior geopolitical advisor to USSpecial Operations Forces in Iraq and Afghanistan. From 2002-5, he was the Global Governance Fellow at the Brookings Institution; from 2000-2002 he worked at the World Economic Forum in Geneva; and from 1999-2000, he was a Research Associate at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. http://www.newamerica.net/publications/articles/2008/waving_goodbye_hegemony_6604 Robert Kagan famously said that America hails from Mars and Europe from Venus, but in reality, Europe is more like Mercury -- carrying a big wallet. The E.U.'s market is the world's largest, European technologies more and more set the global standard and European countries give the most development assistance. And if America and China fight, the world's money will be safely invested in European banks. Many Americans scoffed at the introduction of the euro, claiming it was an overreach that would bring the collapse of the European project. Yet today, Persian Gulf oil exporters are diversifying their currency holdings into euros, and President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad of Iran has proposed that OPEC no longer price its oil in "worthless" dollars. President Hugo Chávez of Venezuela went on to suggest euros. It doesn't help that Congress revealed its true protectionist colors by essentially blocking the Dubai ports deal in 2006. With London taking over (again) as the world's financial capital for stock listing, it's no surprise that China's new state investment fund intends to locate its main Western offices there instead of New York. Meanwhile, America's share of global exchange reserves has dropped to 65 percent. Gisele Bündchen demands to be paid in euros, while Jay-Z drowns in 500 euro notes in a recent video. American soft power seems on the wane even at home.

18 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

***topic links***

19 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

Iraq presence

US presence in Iraq hurts US soft power. Du Boff 03 (Richard, is Professor Emeritus of Economics, Bryn Mawr College, CBS Moneywatch.com, “US hegemony: continuing decline, enduring danger” Dec 03, http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1132/is_7_55/ai_111503528/pg_11/?tag=content;col1, 6/26/10, HR) Meanwhile, two years of "war on terrorism" have fractured the legitimacy of the United States across the world, dealing a blow, in effect, to the ideology and culture of American imperialism. The war on Iraq, a Pew Global Attitudes survey found, "widened the rift between Americans and Western Europeans, further inflamed the Muslim world, softened support for the war on terrorism, and significantly weakened global public support for the North Atlantic Alliance." Only seven of twenty foreign nations surveyed had a favorable view of the United States, and in those nations (Britain, Israel, Kuwait, Canada, Nigeria, Italy, Australia) support was falling. In a British Broadcasting Corporation sampling of opinion in eleven nations, including the United States and only one Arab nation (Jordan), two-thirds of those questioned saw the United States as an arrogant superpower that poses a greater threat to peace than North Korea and Iran (the two surviving "axis of evil" members), and only 25 percent, excluding Americans, said U.S. military might was making the world a safer place. A Transatlantic Trends Survey conducted in July 2003 by the German Marshall Fund of the United States and the Compagnia di San Paolo, a Turin (Italy) foundation showed that only 8 percent of all Europeans questioned thought it "very desirable" that the United States exert strong leadership in world affairs; 70 percent in France and 50 percent in Germany and Italy deemed it "undesirable." (16)

20 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

Middle east drawdowns

U.S. drawdown will increase credibility in the middle east but Iran could quickly drawn interest and trade off Wehrey, Dassa Kaye, Watkins, Martini, Guffey 10 (“The Iraq Effect: The Middle East After the Iraq War” Frederic D.Phil. student in international relations, St. Antony's College, Oxford University; M.A. in Near Eastern studies, Princeton University; B.A. in history, Occidental College, Dalia Ph.D., M.A. and B.A. in political science, University of California, Berkeley, Jessica, Jeffrey, Robert A. RAND Corporation. http://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG892/ 6/26/10 RCM) Regional concerns related to growing Iranian influence after the war were compounded by a perception that the heavy U.S. commitment in Iraq constrained its ability to project power and enforce regional security. Specifically, the difficulties of prosecuting the war in Iraq have fed the view that the American “moment” in the Middle East may be waning, or at a minimum, that the war has clipped the Americans’ wings. However, despite diminished standing in the region, the United States remains the balancer of choice, and the U.S. drawdown from Iraq may enable the United States to regain regional confidence if it proceeds smoothly. The draining effect of the war in Iraq on U.S. resources and military readiness is advanced as the principal reason behind the United States’ declining influence in the region (al-Rukabi, 2008). Despite recent improvement in the security situation in Iraq, many regional observers believe that the war in Iraq has revealed the limits of U.S. power. Similarly, the rise of Iranian influence inside Iraq and the continued development of its missile technology and nuclear program are cited as harbingers of a new regional security order, in which Iran will play an increasingly assertive role at the expense of U.S. interests (Harb, 2008). In an article in the Arab Journal of Political Science, ‘Abdullah al-Shaiji observes,

21 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

Afghanistan/Iraq

Withdrawing troops will set the stage up for a transition to soft power Grossman 10 ( Jerome, February 27, 2010., political activist and commentator, particularly on the issues of weapons of mass destruction and nuclear weapons, http://relentlessliberal.blogspot.com/2010/02/americas-soft- power.html) The United States cannot solve the problems of the world on its own, and the world cannot solve them without the United States. As the world’s only remaining superpower, America has the ability to affect the behavior of other nations through coercion, economic strength and the power of attraction. Hard power relies on coercion and raw economic power. Soft power influences others through public diplomacy, broadcasting, exchange programs, development assistance, disaster relief, exchange of ideas and culture - everything from Hollywood to Shakespeare to orchestras. In his inaugural address, President Barack Obama informed all countries, friendly and unfriendly, that there was a new attitude in the White House. He advised those countries “on the wrong side of history” that the United States “will extend a hand if you are willing to unclench your fist”. During his first year in office, Obama followed through by launching negotiations with Iran and North Korea on their nuclear programs, searching for common ground with Russia on arms control and missile defense, and softening economic sanctions against Cuba. The jury is still out on whether the Obama initiatives will bear fruit, but it is a start and a welcome improvement from the George W. Bush reliance on hard power. But much more must be done to translate Obama’s effective rhetoric into a softening of policy, a softening more likely to increase the security of America and the rest of the world. If President Obama were to withdraw American troops from Iraq and Afghanistan, then reduce the enormous US military budget, close some of the 761 US military bases in 147 countries, he would set the stage for America to inspire and lead the world by using the panoply of its soft power.

22 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

***unilateralism***

23 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

Unilateralism 1nc

Increasing soft power decreases unilateralism Jaime Coronado (Department of Latin American and Iberian Studies, University of Guadalajara ) 2005“Between Soft Power and a Hard Place: Dilemnas of the Bush Doctrine for Inter-American Relations, Journal of Developing Societies, http://jds.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/21/3-4/321, Multilateralism and diplomacy are weakened while unilateralism and coercion are strengthened. The official declaration regarding the existence of an ‘Axis of Evil’ represented by the countries the US ruling elite considers is supporting, financing or not sufficiently fighting against terrorism creates the possibility of an expanding set of targets and enemies list. The Bush administration challenged all countries to define themselves around support for US actions in the post 9/11 scenario, by restating unambiguously the Karl Schmidt ‘friend-foe’ principle: ‘Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists.’ Congruent with the neo-conservative pre-9/11 proto- doctrines discussed above (Wolfowitz, Kristol, Kagan, Rice), the US government declared that it could unilaterally perform ‘preventive strikes’ in case it perceived its security being in danger. The administration passed over the UN Security Council and unilaterally invaded Iraq, alleging an imminent threat posed by non-existent weapons of mass destruction, and subsequently attempted to legitimize its intervention by summoning a multilateral occupation force and calling the UN to get involved. The Bush administration confirmed its opposition to the International Criminal Court and lobbied for bilateral agreements to provide immunity to its citizens, including its officials and security forces. Thus, it reinforced its disdainful position towards international legal regimes, a stand it had already taken when it decided to withdraw from the Anti- Ballistic Missile Treaty and not to ratify the Kyoto Protocol. This unilateralism even extended to the WTO on the issue of steel imports, though it eventually relented under economic pressure .

Unilat key leadership Dr Frank Harvey (Director of the Center for Foreign Policy Studies at Dalhousie University) August 2002 “GLOBALISM, TERRORISM and PROLIFERATION: Unilateral vs. Multilateral Approaches to Security After 9/11 and the Implications for Canada” Two final points should be noted regarding the ‘choice’ between multilateralism and unilateralism. First, policy choices are not always a matter of ‘preferences’ but rather are products of systemic pressures that push leaders in one or another direction – imperatives, not choices, explain behaviour. “People and countries might shape systems, but systems shape countries and people. It is impossible to divorce the exercise of power from the context in which it is set….A singularly unipolar political structure will produce, absolutely inevitably, a unilateralist outcome….The sole viable alternative to unilateralism is not multilateralism, but isolationism.”59 In order to protect their own security and economic imperatives after 9/11, European, Canadian and Russian leaders simply cannot afford American isolationism and will reluctantly come to support almost any U.S. foreign policy initiative (unilateral or multilateral), even while criticizing the approach in public . Second, the unilateralism-multilateralism debate often creates a false dichotomy – there are no pure unilateralists or multi-lateralists, and ones preferences are likely to vary from issue to issue, region to region, threat to threat. Historically, American foreign policy has exhibited elements of both strategies – in fact, some recent descriptions of contemporary U.S. strategy include multiple bilateralism and à la carte multilateralism. But Washington tends to receive far more criticism for its unilateral initiatives than praise for its contributions to multilateralism. This often creates an exaggerated impression that Washington prefers unilateralism even when the record is more balanced. However, when it comes to American ‘security’ after 9/11 unilateral priorities are likely to prevail for the many reasons outlined in this report. In essence, multilateralism has become a liability and a security threat. It is perceived by Washington today as “a strategy by smaller states to tie the U.S. down like Gulliver among the Lilliputians. It is no wonder that France prefers a multi-polar and multilateral world, and less developed countries see multilateralism as in their interests, because it gives them some leverage on the United States.” These states are not driven by some higher moral imperative to create a truly global order based justice and international law; they are motivated by the same fundamental imperatives that drive American foreign policy: power, security, self interest and survival.

Extinction Khalilzad, 95 Under the third option, the United States would seek to retain global leadership and to preclude the rise of a global rival or a return to multipolarity for the indefinite future. On balance, this is the best long-term guiding principle and vision. Such a vision is desirable not as an end in itself, but because a world in which the United States exercises leadership would have tremendous advantages. First, the global environment would be more open and more receptive to American values -- democracy, free markets, and the rule of law. Second, such a world would have a better chance of dealing cooperatively with the world's major problems, such as nuclear proliferation, threats of regional hegemony by renegade states, and low-level conflicts. Finally, U.S. leadership would help preclude the rise of another hostile global rival, enabling the United States and the world to avoid another global cold or hot war and all the attendant dangers, including a global nuclear exchange. U.S. leadership would therefore be more conducive to global stability than a bipolar or a multipolar balance of power system.

24 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

2nc unilateralism link

Soft power destroys US unilateralism – this evidence is reverse causal Joseph Nye (Dean at Harvard) une 13 2002 International Herald Tribune Many American allies say they resent the excessive unilateralism of the Bush administration's foreign policy. Ironically, in the 2000 election campaign, candidate George W. Bush aptly made the best case for a multilateral approach: "If we are an arrogant nation, they'll view us that way, but if we're a humble nation, they'll respect us." International rules bind America and limit its freedom of action, but they serve U.S. interests by binding others as well. And opportunities for foreigners to raise their voice and influence American policies constitute an important incentive for alliance. U.S. membership in a web of multilateral institutions ranging from the United Nations to NATO reduces U.S. policy autonomy. But, seen in the light of a constitutional bargain, the multilateralism of U.S. preeminence reduces the incentives for constructing alliances against America. Multilateralism is a matter of degree, and not all multilateral arrangements are good. Like other countries, the United States should occasionally use unilateral tactics. So how to choose? No country can rule out unilateral action in cases that involve vital survival interests. Self-defense is permitted under Article 51 of the UN Charter. Bush's military action in Afghanistan was largely unilateral, but was carried out against a backdrop of support from NATO allies and UN resolutions. Even when survival is not at stake, unilateral tactics sometimes help lead others to compromises that advance multilateral interests. During the Reagan administration, trade legislation that threatened unilateral sanctions if others did not negotiate helped create conditions that prodded other countries to move forward with the World Trade Organization and its dispute settlements mechanism. Some multilateral initiatives are recipes for inaction, or are contrary to American values. For example, the "new international information order" proposed by Unesco in the 1970s would have helped authoritarian governments to restrict freedom of the press. More recently, Russia and China prevented Security Council authorization of intervention to stop the human rights violations in Kosovo in 1999. Ultimately the United States decided to go ahead without Security Council approval. Even then the American intervention was not purely unilateral but carried out with strong support from allies in NATO. Some transnational issues are inherently multilateral and cannot be managed without the help of other countries. Climate change is a perfect example. The United States is the largest source of greenhouse gases, but three-quarters of the sources originate outside its borders. Without cooperation, the problem is beyond American control. The same is true of a long list of items: the spread of infectious diseases, the stability of global financial markets, the international trade system, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, narcotics trafficking, international crime syndicates, transnational terrorism. In addition, multilateralism is a means to get others to share the burden of providing public goods. Sharing also helps foster commitment to common values. Even militarily, the United States should rarely intervene alone. (Polls show that two-thirds of Americans prefer multilateral actions.) It pays a minority share of UN and NATO peacekeeping operations, and the legitimacy of a multilateral umbrella reduces collateral political costs. In choosing between multilateral and unilateral tactics, Washington should consider the effects of the decision on U.S. soft power, which can be destroyed by excessive unilateralism and arrogance. In balancing whether to use multilateral or unilateral tactics, or to adhere to or refuse to go along with particular multilateral initiatives, Americans have to consider how to explain their actions to others and what the effects will be on their soft power. In short, American foreign policy should have a general preference for multilateralism, but not all multilateralism. At times, America will have to go it alone. When it does so in pursuit of public goods which benefit others as well as Americans, the nature of the ends may substitute for the means in making U.S. power acceptable in the eyes of others. If America first makes an effort to consult others and try a multilateral approach, its occasional unilateral tactics are more likely to be forgiven. But if it succumbs to the unilateralist temptation too easily, it invites the criticisms that the Bush administration now faces. Moreover, America will often fail because of the intrinsically multilateral nature of transnational issues in a global age, and there will be costly effects on U.S. soft power.

Soft power causes coalitions – kills unilateralism Joseph Nye (Dean at Harvard) April 14 2002 “This is No Time for Unilateralism”, Op-Ed, Boston Globe And many of these transnational issues cannot be solved unilaterally or by theuse of military power.The good news for Americans is that the United States will likely remainthe world''s single most powerful country well into this new century. While potential coalitions to check American power could be created, it is unlikely that they would become firm alliances unless the United States handles its hard coercive power in an overbearing unilateral manner that undermines our attractive or soft power. As the German editor Joseph Joffe has written, "unlike centuries past,when war was the great arbiter, today the most interesting types ofpower do not come out of the barrel of a gun . . . Today there is a muchbigger payoff in `getting others to want what you want,'' and that has todo with cultural attraction and ideology and agenda setting . . ."On these measures, China, Russia, Japan, and even Western Europecannot match the influence of the United States. The United States could squander this soft power by heavy-handed unilateralism. The bad news for Americans in this three-dimensional power game of the21st century is that there are more and more things outside the control ofeven a superpower, such as international financial stability, controlling thespread of infectious diseases, cyber-crime and terrorism.Although the United States does well on the traditional measures, there isincreasingly more going on in the world that those measures fail tocapture. We must mobilize international coalitions to address sharedthreats and challenges.America needs the help and respect of other nations. We will be in troubleif our unilateralism prevents us from getting it.

25 MGW 2010 Soft power bad Petit/Grove Lab Never Again

2nc proliferation impact