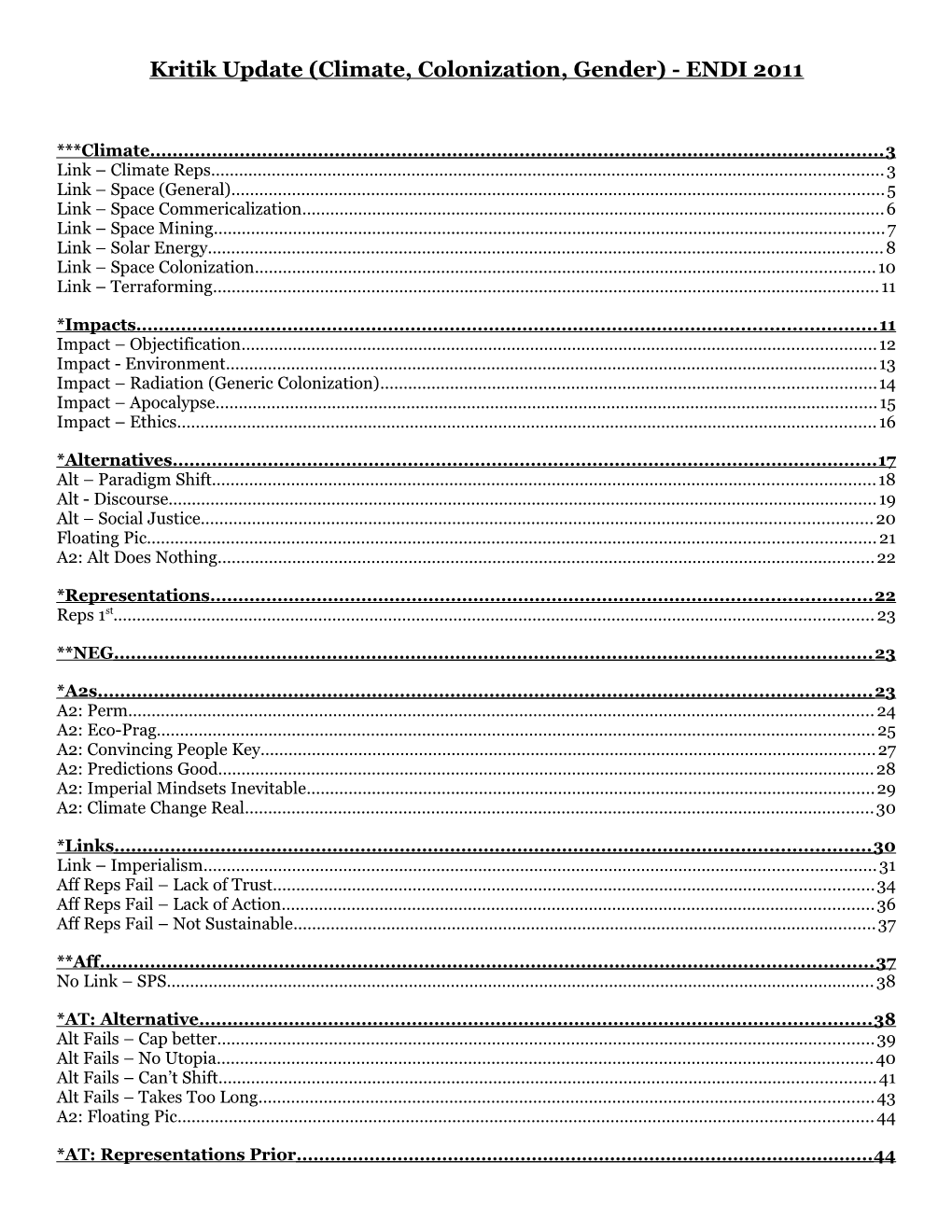

Kritik Update (Climate, Colonization, Gender) - ENDI 2011

***Climate ...... 3 Link – Climate Reps...... 3 Link – Space (General)...... 5 Link – Space Commericalization...... 6 Link – Space Mining...... 7 Link – Solar Energy...... 8 Link – Space Colonization...... 10 Link – Terraforming...... 11

*Impacts ...... 11 Impact – Objectification...... 12 Impact - Environment...... 13 Impact – Radiation (Generic Colonization)...... 14 Impact – Apocalypse...... 15 Impact – Ethics...... 16

*Alternatives ...... 17 Alt – Paradigm Shift...... 18 Alt - Discourse...... 19 Alt – Social Justice...... 20 Floating Pic...... 21 A2: Alt Does Nothing...... 22

*Representations ...... 22 Reps 1st...... 23

**NEG ...... 23

*A2s ...... 23 A2: Perm...... 24 A2: Eco-Prag...... 25 A2: Convincing People Key...... 27 A2: Predictions Good...... 28 A2: Imperial Mindsets Inevitable...... 29 A2: Climate Change Real...... 30

*Links ...... 30 Link – Imperialism...... 31 Aff Reps Fail – Lack of Trust...... 34 Aff Reps Fail – Lack of Action...... 36 Aff Reps Fail – Not Sustainable...... 37

**Aff ...... 37 No Link – SPS...... 38

*AT: Alternative ...... 38 Alt Fails – Cap better...... 39 Alt Fails – No Utopia...... 40 Alt Fails – Can’t Shift...... 41 Alt Fails – Takes Too Long...... 43 A2: Floating Pic...... 44

*AT: Representations Prior ...... 44 A2: Reps 1st...... 45 Our Reps Good – environment...... 46

*Other ...... 47 Dickens & Ormrod Indict...... 48 Climate Discourse Good...... 49 Climate Change Real...... 50 A2: Root Cause...... 51 Perm...... 52

***Colonization ...... 53

**Neg ...... 53

*1nc ...... 53

*A2s ...... 55 A2: Perm...... 56

*Links ...... 56 Link – Generic...... 57 Link – Rhetoric...... 58 Link – Colonization...... 59 Link – Exploration...... 61 Link – SPS...... 63 Link – Space Mining...... 64 Link – Hegemony...... 65 Link – Machines...... 66

*Impacts ...... 66 Impact – Environment...... 67 Impact – Abandonment...... 69 Impact – Extinction...... 70 Impact – Awareness...... 71 Impact Turns Case...... 72 Impact Turns Warming...... 73

**Aff ...... 73

*Link Debate ...... 74 No Link...... 75 No Link – Double Bind...... 76

*Other ...... 76 A2: Value To Life...... 77 Climate Science True...... 78 Rhetoric Inevitable...... 79

***Surveillance ...... 79

**Neg ...... 80

*Links ...... 81 Link – Monitoring...... 82 Link – Climate Research...... 83 Link – Data Collection...... 84

*Impacts ...... 84 Impact – Value to Life...... 85 Impact – Environment...... 86 Impact – Lack of Boundaries...... 88

*Alts ...... 88 Alt – New Thinking...... 89

***Gender ...... 90

**Neg ...... 91

*Links ...... 92 Link – Development...... 93 Link – Technology...... 94 Link – Science...... 95 Link – Climate...... 99 Link – Risk Analysis...... 101

*Impacts ...... 102 Impact – Value to Life...... 103 Impact – Social Division...... 104

*Alts ...... 104 Alt – Re-thinking...... 105 Alt – Critical Sociology...... 106 Alt – Change Risk Analysis...... 107 Alt – Public Involvement...... 109

*Representations ...... 110 Reps Shape Reality...... 111

*A2s ...... 111 A2: Females in NASA...... 112

*Links ...... 112 Link – NASA...... 113 Link – Human Space-flight...... 115 Link – Space NMD...... 117 Link – Star Wars Performance...... 118

**Aff ...... 118

*Other ...... 119 A2: Eco-Fem...... 120

***Science ...... 121

**Neg ...... 122

*A2s ...... 123 A2: Need Realism...... 124

**Aff ...... 124

*Alt Debate ...... 125 Alt Fails – Need Institutions...... 126

*Other ...... 126 Author Indicts...... 127

***Public Health ...... 128

**Public-Health/Disease Links ...... 128

***Climate Link – Climate Reps

Apocalyptic framing of climate change eliminates political response in favor technological management. Their framing prevents changes in distribution and consumption required to cope with climate change.

Erik SWYNGEDOUW Geography @ Manchester ’10 “Apocalypse Forever?: Post-political populism and the spectre of climate change” Theory, Culture, and Society 27 (2-3) p. 216-219

The Desire for the Apocalypse and the Fetishization of CO2 It is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism. (Jameson, 2003: 73) We shall start from the attractions of the apocalyptic imaginaries that infuse the climate change debate and through which much of the public concern with the climate change argument is sustained. The distinct millennialist discourse around the climate has co-produced a widespread consensus that the earth and many of its component parts are in an ecological bind that may short-circuit human and non-human life in the not too distant future if urgent and immediate action to retrofit nature to a more benign equilibrium is postponed for much longer. Irrespective of the particular views of Nature held by different individuals and social groups, consensus has emerged over the seriousness of the environmental condition and the precariousness of our socio-ecological balance (Swyngedouw, forthcoming). BP has rebranded itself as ‘Beyond Petroleum’ to certify its environmental credentials, Shell plays a more eco-sensitive tune, eco-activists of various political or ideological stripes and colours engage in direct action in the name of saving the planet, New Age post-materialists join the chorus that laments the irreversible decline of ecological amenities, eminent scientists enter the public domain to warn of pending ecological catastrophe, politicians try to outmanoeuvre each other in brandishing the ecological banner, and a wide range of policy initiatives and practices, performed under the motif of ‘sustainability’, are discussed, conceived and implemented at all geographical scales. Al Gore’s evangelical film An Inconvenient Truth won him the Nobel Peace price, surely one of the most telling illustrations of how eco - logical matters are elevated to the terrain of a global humanitarian cause (see also Giddens, 2009). While there is certainly no agreement on what exactly Nature is and how to relate to it, there is a virtually unchallenged consensus over the need to be more ‘environmentally’ sustainable if disaster is to be avoided; a climatic sustainability that centres around stabilizing the CO2 content in the atmosphere (Boykoff et al., forthcoming). This consensual framing is itself sustained by a particular scientific discourse.1 The complex translation and articulation between what Bruno Latour (2004) would call matters of fact versus matters of concern has been thoroughly short-circuited. The changing atmospheric composition, marked by increasing levels of CO2 and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, is largely caused by anthropogenic activity, primarily (although not exclusively) as a result of the burning of fossilized or captured CO2 (in the form of oil, gas, coal, wood) and the disappearance of CO2 sinks and their associated capture processes (through deforestation for example). These undisputed matters of fact are, without proper political intermediation, translated into matters of concern. The latter, of course, are eminently political in nature. Yet, in the climate change debate, the political nature of matters of concern is disavowed to the extent that the facts in themselves are elevated, through a short-circuiting procedure, on to the terrain of the political, where climate change is framed as a global humanitarian cause. The matters of concern are thereby relegated to a terrain beyond dispute, to one that does not permit dissensus or disagreement. Scientific expertise becomes the foundation and guarantee for properly constituted politics/ policies. In this consensual setting, environmental problems are generally staged as universally threatening to the survival of humankind, announcing the premature termination of civilization as we know it and sustained by what Mike Davis (1999) aptly called ‘ecologies of fear’. The discursive matrix through which the contemporary meaning of the environmental condition is woven is one quilted systematically by the continuous invocation of fear and danger, the spectre of ecological annihilation or at least seriously distressed socio-ecological conditions for many people in the near future. ‘Fear’ is indeed the crucial node through which much of the current environmental narrative is woven, and continues to feed the concern with ‘sustainability’. This cultivation of ‘ecologies of fear’, in turn, is sustained in part by a particular set of phantasmagorical imaginaries (Katz, 1995). The apocalyptic imaginary of a world without water, or at least with endemic water shortages, ravaged by hurricanes whose intensity is amplified by climate change; pictures of scorched land as global warming shifts the geopluvial regime and the spatial variability of droughts and floods; icebergs that disintegrate around the poles as ice melts into the sea, causing the sea level to rise; alarming reductions in biodiversity as species disappear or are threatened by extinction; post-apocalyptic images of waste lands reminiscent of the silent ecologies of the region around Chernobyl; the threat of peak-oil that, without proper management and technologically innovative foresight, would return society to a Stone Age existence; the devastation of wildfires, tsunamis, diseases like SARS, avian flu, Ebola or HIV, all these imaginaries of a Nature out of synch, destabilized, threatening and out ofcontrol are paralleled by equally disturbing images of a society that continues piling up waste, pumping CO2 into the atmosphere, deforesting the earth, etc. This is a process that Neil Smith appropriately refers to as ‘nature-washing’ (2008: 245). In sum, our ecological predicament is sutured by millennial fears, sustained by an apocalyptic rhetoric and representational tactics, and by a series of performative gestures signalling an overwhelming, mind-boggling danger, one that threatens to undermine the very coordinates of our everyday lives and routines, and may shake up the foundations of all we took and take for granted. Table 1 exemplifies some of the imaginaries that are continuously invoked. Of course, apocalyptic imaginaries have been around for a long time as an integral part of Western thought, first of Christianity and later emerging as the underbelly of fast-forwarding technological modernization and its associated doomsday thinkers. However, present-day millennialism preaches an apocalypse without the promise of redemption. Saint John’s biblical apocalypse, for example, found its redemption in God’s infinite love. The proliferation of modern apocalyptic imaginaries also held up the promise of redemption: the horsemen of the apocalypse, whether riding under the name of the proletariat, technology or capitalism, could be tamed with appropriate political and social revolutions. As Martin Jay argued, while traditional apocalyptic versions still held out the hope for redemption, for a ‘second coming’, for the promise of a ‘new dawn’, environmental apocalyptic imaginaries are ‘leaving behind any hope of rebirth or renewal . . . in favour of an unquenchable fascination with being on the verge of an end that never comes’ (1994: 33). The emergence of newforms of millennialism around the environmental nexus is of a particular kind that promises neither redemption nor realization. As Klaus Scherpe (1987) insists, this is not simply apocalypse now, but apocalypse forever. It is a vision that does not suggest, prefigure or expect the necessity of an event that will alter history. Derrida (referring to the nuclear threat in the 1980s) sums this up most succinctly: . . . here, precisely, is announced – as promise or as threat – an apocalypse without apocalypse, an apocalypse without vision, without truth, without revelation . . . without message and without destination, without sender and without decidable addressee . . . an apocalypse beyond good and evil. (1992: 66) The environmentally apocalyptic future, forever postponed, neither promises redemption nor does it possess a name; it is pure negativity. The attractions of such an apocalyptic imaginary are related to a series of characteristics. In contrast to standard left arguments about the apocalyptic dynamics of unbridled capitalism (Mike Davis is a great exemplar of this; see Davis, 1999, 2002), I would argue that sustaining and nurturing apocalyptic imaginaries is an integral and vital part of the new cultural politics of capitalism (Boltanski and Chiapello, 2007) for which the management of fear is a central leitmotif (Badiou, 2007). At the symbolic level, apocalyptic imaginaries are extraordinarily powerful in disavowing or displacing social conflict and antagonisms. As such, apocalyptic imaginations are decidedly populist and foreclose a proper political framing. Or, in other words, the presentation of climate change as a global humanitarian cause produces a thoroughly depoliticized imaginary, one that does not revolve around choosing one trajectory rather than another, one that is not articulated with specific political programs or socio-ecological project or revolutions. It is this sort of mobilization without political issue that led Alain Badiou to state that ‘ecology is the new opium for the masses’, whereby the nurturing of the promise of a more benign retrofitted climate exhausts the horizon of our aspirations and imaginations (Badiou, 2008; Žižek, 2008). We have to make sure that radical techno- managerial and socio-cultural transformations, organized within the horizons of a capitalist order that is beyond dispute, are initiated that retrofit the climate (Swyngedouw, forthcoming). In other words, we have to change radically, but within the contours of the existing state of the situation – ‘the partition of the sensible’ in Rancière’s (1998) words, so that nothing really has to change.

Scientific framing of climate change stalls social change. We need to develop and alternative frame to respond to climate change. Brian Wynne, Research Director of the Centre for the Study of Environmental Change (CSEC) at the University of Lancaster, 10 Theory, Culture, and Society, “Strange Weather, Again : Climate Science as Political Art, 2010, Volume 27 P. 289-306 [Marcus]

Significantly, we can note the open-endedly experimental nature of this original commitment – (paraphrasing) ‘is long-term climate prediction a scientifically do-able problem?’ (Clarke and Fujimura, 1994). This is not unlike many other such large and ambitiously open-ended scientific research commitments. However, it is also notable how the original meaning of the intellectual enterprise changes in light of the large and long-term organization and the proliferating commitments involved, which were at the original moment of commitment unknown and unknowable. With the scientific modelling which became the central currency of the later IPCC and its definitive global scientific advice to policy leaders, media and civil society networks, pragmatic commitments and choices were necessarily made along the way. The original perfectly explicit founding question, ‘Is long-term climate prediction scientifically do-able?’, has been answered by default, and is no longer explicitly posed. Yet neither has it been deliberately and directly resolved as the attention has necessarily switched to more detailed technical questions. Strictly speaking, we still do not know the answer. In one sense the answer seems to be positive – after all, long-term climate prediction is ‘being done’ and, moreover, momentous, even unprecedentedly ambitious attempted political authority is being invested in a positive answer to that question. But these predictions can claim authority to predict credibly and reliably only in very complex and indirect ways – effectively only by default of evident failure. As Douglas (1971) suggested, like any other science these attempts at long-term prediction cannot require assent, as if a universal intellectual necessity. This is especially so when normative ‘requirements’ are woven into and confused with the propositional assertions about future climate-states and their causes. Indeed what it would mean to demonstrate the answer – do-able or not? yes or no? – is itself negotiable. Is the key aim to show the future effect on climate (which variables and scales?) of human-emitted greenhouse gas increases? Or of the aggregate of these and natural changes? How might excluded but credible factors like abrupt discontinuous changes from known positive climate feedbacks (which are omitted from existing models) influence the perceived validity and success or failure of IPCC long-term predictions? Ultimately these scientific frames of meaning and ‘demonstration’ depend partly on broader human frames of meaning, such as whether we attach significance to multiple independent possible influences on observed climate changes, both slow and relatively abrupt ones, or only those for which human society is responsible. If the relative importance of the human contributions compared with the non-human ones is unknown, perhaps unknowable, do we then still assume responsibility for our part, or fatalistically declare that there can be no human responsibility if sun-spots and other factors way beyond human agency are also influencing climate? Link – Space (General)

Using space as a “means to an end” re-entrenches its exploitation. Peter DICKENS Lecturer Sociology @ Cambridge AND James ORMROD, Lecturer in sociology at University of Brighton, 07 “Outer Space and Internal Nature: Towards a Sociology of the Universe” Sociology 41 (4) p. 143 [Marcus]

Our point is that ‘the heavens’ are now being envisaged, at least by dominant social orders, in a form very similar to Earthly nature. They too are being made into Baconian objects, as means towards ends. They exist to be used, to be lived in, to be worked on and to be domesticated and dominated by society. Such a view has long been prevalent in human society, especially Western society. But now that access to outer space is becoming feasible the same values and orientation are being extended to outer space by extremely influential classes of people. The exploitation of space continues apace. Mary-Ann Elliott, for example, is a ‘space broker’ working in this sector. She has recently announced that ‘over the last five years we’ve grown 1061 per cent’. Jim Benson is another space broker. ‘Natural resources in space’, he informs us, ‘are on a first come first served basis’ (ABC Australia 2005). Link – Space Commericalization Space commercialization supports a flawed US profit only mindset. Peter DICKENS Lecturer Sociology @ Cambridge AND James ORMROD, Lecturer in sociology at University of Brighton, 07 “Outer Space and Internal Nature: Towards a Sociology of the Universe” Sociology 41 (4) p. 144 [Marcus]

Private corporations have always been used to make and maintain space activities funded by the US government, but there is a trend towards increasing private sector participation, especially through new competition schemes. This process is part of a much more general trend that has been experienced by almost all societies since the 1980s. Now, as we have seen, it is being extended to the military and to surveillance. Previously state-run activities are being contracted out to the private sector. But, furthermore, space activities are now being envisaged as profitable in themselves, and so space activity is now becoming increasingly commercialized as well as privatized. This is another stage of Luxemburg’s restless search for further profits or of what Harvey (2003) calls ‘accumulation by dispossession’. Using outer space as a source of raw materials is one suggestion under very active consideration. Harnessing the Sun’s rays with solar panels in space and beaming the energy to electricity grids via Earth-bound receivers is another kind of outer spatial fix under discussion, though it is not seen as profitable within the next twenty years. In the more distant future humanization will further encroach on its ‘outside’, making planets into zones appropriated for the further expansion of capitalism. Link – Space Mining

The idea that we can mine outer space for minerals is based on a flawed world approach. Peter DICKENS Lecturer Sociology @ Cambridge AND James ORMROD, Lecturer in sociology at University of Brighton, 07 “Outer Space and Internal Nature: Towards a Sociology of the Universe” Sociology 41 (4) p. 144 [Marcus]

Outer space is now increasingly envisaged as providing inputs to the Earthly production process. It is, for example, seen as an unlimited source of metals for human use. Private companies have also been established working on the research and design for asteroidal and lunar mines. This is discussed in a number of books elaborating the commercial potential of outer space (e.g. Lewis 1996; Zubrin 1999; Hudgins 2002). The expansion of industry into space has been referred to by Harry G. Stine (1975) as the ‘third industrial revolution’ and by Krafft Ehricke (1972) as ‘the benign industrial revolution’ (as there were supposedly no environmental issues associated with it). Asteroids are receiving special attention (Lewis 1996). The Moon might seem an obvious first target for the acquisition and mining of resources, but asteroids are currently seen as a better bet thanks to their metallic density. They have three hundred times as much free metal as an equal mass taken from the Moon. Metals found on the Moon are just the dispersed debris from asteroids. In the mid-1990s the market value of metals in the smallest known asteroid, known as 3554 Amun, was about $20 trillion. This included $8 trillion worth of iron and nickel, $6 trillion worth of cobalt, and about $6 trillion in platinum-group metals (ibid.). As and when it is possible to launch thousands of people into orbit and build giant solar power satellites, Lewis argues, it should be possible to retrieve this and mine other asteroids to supply Earth with all the metals society will ever need. Extracting valuable helium-3 from the Moon is another possibility. One metric ton of helium-3 is worth $3 million, and one million tons could be obtained from the Moon. This has led Lawrence Joseph to question in a New York Times article whether the Moon could become the Persian Gulf of the twenty-first century (cited in Gagnon 2006). Needless to say, we need to remain cautious in accepting these highly optimistic forecasts. Even the most enthusiastic pro-space activists see materials in space as useful only for building in space. The cost of returning materials to Earth would add so much to the cost of extracting them that this would never be financially viable. Research is also being conducted, however, into the production of fuel for further humanization from space materials (Zubrin and Wagner 1996). NASA has recently given the chemical engineer Jonathan Whitlow a grant of nearly $50,000 to develop computer models that could lead to the production of propellant from the lunar regolith or rock mantle (SPX 2004). The issue of ownership of means of production is again vitally important here. United Nations legislation and the most optimistic proponents of space exploitation assume that space resources are infinite and there will be enough for everyone to own plenty of space. Considering the immensity of space as a whole, this is of course true. But it is overlooked that the nearer parts of space are those which are most profitable and viable to exploit. In reality, the part of space that is not yet owned and exploited will always become further and further from the Earth, and as this happens investors will need to be increasingly wealthy to afford to exploit it. Link – Solar Energy

Giant technological projects like SPS foreclose our social relations that guide energy usage. Trying to maintain more of the same encourages environmental degradation.

John BYRNE Center for Energy & Environmental Policy, University of Delaware ET AL ‘9 “Relocating Energy in the Social Commons” Bulletin of Science,Technology & Society 29 (2) p. 81-82

Interestingly, Tierney (and all but one of the article’s 114 commenters) missed a key aspect of the soft path critique. Lovins’ (1977) soft path calls for the “rapid development of renewable energy sources matched in scale and in energy quality to end use needs” (p. 25) By design, hard path systems supply, rather than match, needs and intentionally disregard social definitions of scale and quality in favor of technical and, when it suits, certain environmental factors. In this way, hard path strategies ignore what soft paths insist on—a significant rethinking of the social relationship to energy (Byrne & Toly, 2006). Whether the response to our energy and climate challenges should be nuclear or some other option, contemporary debates about these issues have almost entirely focused on them as technology questions. With a looming climate crisis caused in large part by the energy sector,2 one might hope that social concerns would rival technical ones. But so far, this has not been the case. Instead, technology fixes of various kinds appear to have the momentum. An unexpected ally supporting technology-based answers has emerged in middle class environmentalism. Backed by the Sierra Club and others who have partnered with renewable energy business lobbies such as the American Wind Energy Association (AWEA), mainstream environmentalism is calling for a renewable energy version of the Manhattan Project (see, e.g., AWEA, 2008; Wilson, 2008). Although the choice of technology differs, the prescriptions of Tierney and large environmental organizations agree on several points. There is consensus that a quick end to modern use of fossil fuels is necessary; the sooner, the better. As a business proposal, this naturally spells good news for the two industries. A second shared belief is that the new energy order must represent a dramatic shift to electricity, powering everything from home heating to factories and vehicles with electrons. A third component of the shared ideology is to construct the new Manhattan Project on the foundations of the modern electric grid. Ubiquitous, sophisticated, and, above all, centralized in architecture from technical design to management, the grid represents our best hope, according to the renewable energy and nuclear power proponents, for speedy, large action. Other strategies are thought to be impractical and costly if they require a different infrastructure; time and money are in short supply, precluding a solution before environmental and, now, economic calamity hits. As the two industries vie for primacy in creating a green energy system, many see a cause for celebration. Whoever wins, a low-carbon future sustained by green jobs and a green economy of consumption and production awaits. Indeed, a breathtaking confidence bubbles forth as the global financial meltdown and ecosystem collapse are both forecast to be overcome. In the hearts and minds of enthusiasts, there can be no excuse for inaction (compare AWEA, 2008 and Tucker, 2008). For all the celebration, though, there is a disconcerting feature: the energy revolution summoned by the two camps appears to proceed without serious social change. The hard path preference to supply energy rather than transform society-energy relations informs the new vision. Curiously, the leaders of the revolt are to be the same actors who built the modern (now disgraced) energy scheme. Huge electric utilities, megatechnical companies such as Siemens and General Electric (making nuclear plants and giant wind turbines), and finance mammoths like Goldman Sachs and J. P. Morgan Stanley (who have been equally prepared to underwrite nuclear and renewable energy monuments as long asthe dollar amounts are in the billions) are to save the planet, maintain economic growth, and, of course,make money. The prospect of yet another corporate-led technology revolution (alongside the “dot.com,” “information highway,” “biotechnology,” and “microelectronic” revolutions of recent times), in this instance to decarbonize the energy sector, is welcomed by some and skeptically viewed by others. Still, momentum rests with the oddly allied proponents of the new energy order. Why? Embedded in the urgent call-to-action is a shared, near-desperate sense that without a “Manhattan Project for 2009” (Wilson, 2008), collapse is certain. One might think this would lead to an expectation of social sacrifice. However, the middle class roots of the call-to- action work against such a result, shifting attention instead to technology as the source of salvation. As discussed below, the modern energy system gained and has retained political power through this promise. In combination, a curious mix of social fatalism and technological positivism define the current aspiration for an energy revolution and its search for the answer that can avert ruin . . . and yet also forego major social change.

Solar energy only is profitable and usable for the rich – the poor are essentialized. Peter DICKENS Lecturer Sociology @ Cambridge AND James ORMROD, Lecturer in sociology at University of Brighton, 07 “Outer Space and Internal Nature: Towards a Sociology of the Universe” Sociology 41 (4) p. 145 [Marcus]

Outer space is also being seen as an unlimited source of energy for industrial and domestic production. Solar panels are already allowing electricity to be generated in outer space. The International Space Station provides itself with around 80 kilowatts continuously from an acre of solar panels. The principle can in theory be extended to cover much larger satellites generating huge amounts of electrical power (Macauley and Davis 2002). A further suggestion is that this could be converted to microwaves and beamed to Earth via laser beams, providing electricity with no greenhouse gas emissions or toxic waste of any kind. A long-standing dream is for Earth’s power to be projected directly from space, ‘simultaneously providing a large profitable business and dramatically reducing pollution on Earth’ (Globus 2005). Solar panels in space are never obstructed by weather conditions and benefit from the greater intensity of the Sun outside Earth’s atmosphere. If there is a desperate demand for electricity, energy companies could stand to make substantial profits; the station receiving the laser beam would become a new Middle East! On the other hand, they would be transmitting such energy back to Earth via giant laser beams, a prospect likely to generate major risk, especially for those Earthlings near to the point of reception. The idea of using satellites for harnessing solar power was introduced by Glazer (1968), and became central to Gerard O’Neill’s space colony plans discussed below. But we need again to remain cautious. The main criticism is the expense of the electricity they would produce. There are serious questions about its profitability, at least in the short to medium term (Macauley 2000). Those who do not write off the idea completely believe that it will become profitable and viable and may actually happen fairly soon, though requiring some form of private– public partnership or World Bank funding (Collins 2000; Kassing 2000; Woodell 2000). But this will only be at the point when the unit cost of electricity produced by Earthly power sources rises above the unit cost of satellite solar power. According to many estimates this will not be until reserves on Earth are much more depleted. Only then will this particular outer spatial fix become profitable. If it were ever to happen, the energy produced would be extremely expensive and, because of the massive investment it would require, would very likely be monopolized. However, it can be argued that it will simply never be viable because it is cheaper to produce renewable energy on Earth than it would be in space. One commentator (Launius 2003) outlines the argument that equivalent electricity could be produced by covering a section of the Sahara in solar panels, and it would be a great deal cheaper, safer and easier to maintain (Collins (2000) disagrees). To Launius, outer space collectors of solar power look like an excuse for a space programme rather than a legitimate solution to energy problems. Link – Space Colonization Colonization is just another form of “humanizing” the universe Peter DICKENS Lecturer Sociology @ Cambridge AND James ORMROD, Lecturer in sociology at University of Brighton, 07 “Outer Space and Internal Nature: Towards a Sociology of the Universe” Sociology 41 (4) p. 148 [Marcus]

But it is little appreciated that the colonization of outer space has already started with the International Space Station. Here are living quarters for human beings. And here experiments are being conducted on the effects of gravity loss on human beings and other species. George W. Bush’s Space Exploration Initiative includes plans for a permanent lunar base manned in six-month shifts. Other still less exotic forms of humanization are already well in place. We have already encountered humanization in the form of militarization and, via satellites, the surveillance of society and broadcasting information and propaganda. It now seems clear that this process is to be extended, with outer space being envisaged as a source of energy and materials. In the longer term the ‘terraforming’ of nearby planets, making them into environments suitable for human beings, may be possible.

Space Colonization is rooted in an imperial and gendered frame. Peter DICKENS Lecturer Sociology @ Cambridge AND James ORMROD, Lecturer in sociology at University of Brighton, 07 “Outer Space and Internal Nature: Towards a Sociology of the Universe” Sociology 41 (4) p. 150 [Marcus]

Whatever we may think of this equation between gender and types of ‘mastering’, the potential dangers of making new Earth-like planets seem obvious. Here again, humanity’s submission of the planets is being applied on a quick-fix basis and generating potential risks. The planetary engineering project rings alarm bells as the kind of ‘deadly manifestation of bigness’ that Ehrenfeld (1981) had in mind in The Arrogance of Humanism. Indeed, it is a project he cites in that book. It relies on humans’ complete confidence in their ability to master nature for the better. Ehrenfeld says of the history of humanism as he defines it: ‘we have chosen to transform our original faith in a higher authority to faith in the power of reason and human capabilities. It has proved a misplaced trust’ (1981: viii). He points to the failure of other great human projects aimed at controlling nature, though he does not seem to be implying a reversion to a mediaeval deference to religion. As a solution for Earthly problems, planetary engineering also reverberates with Beck’s theory of late modernity (1992, 1994), according to which society is characterized by escalating projects of unprecedented scale and high- consequence risk manufactured by an increasingly global social system. We return to Beck shortly. Link – Terraforming Terraforming ignores social and environmental considerations. Peter DICKENS Lecturer Sociology @ Cambridge AND James ORMROD, Lecturer in sociology at University of Brighton, 07 “Outer Space and Internal Nature: Towards a Sociology of the Universe” Sociology 41 (4) p. 148 [Marcus]

The central idea of terraforming is to enhance the capacity of a planetary environment to support human life (literally to make it Earth-like). This would entail making the surface temperature appropriate for human beings, increasing the mass of the atmosphere, making water available in liquid form, reducing ultraviolet and cosmic rays and making an atmosphere that humans could breathe. If plants are to survive, higher levels of atmospheric oxygen would be needed to enable root respiration (Fogg 1995a,b; Zubrin and Wagner 1996). Mars is usually seen as the most obvious ‘bio-compatible’ candidate for terraforming and eventual occupation by human beings. It appears to contain considerable amounts of frozen water and large quantities of carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen and oxygen. These four elements are the basis of food and water and of plastics, wood, paper and clothing, and even of rocket fuel (Zubrin and Wagner 1996). It is also the right distance from the Sun to be neither too hot nor too cold to rule out life surviving (the so-called ‘Goldilocks effect’). Making a planet such as Mars into a fully terraformed and colonized setting for human beings entails doing the opposite of what many scientists, activists and political regimes are attempting on Earth. While many individuals and governments on Earth are trying to overcome the destabilization of the climate because greenhouse gases are trapping too much of the Sun’s heat, terraformers are actively attempting to make a new greenhouse effect. What are the environmental and social implications of terraforming? These are matters almost wholly missing in the optimistic accounts of scientists and prospace advocates. There are a number of potential risks, dependent on how such planetary engineering is achieved. Perhaps most drastically and dangerously, one proposal is to terraform Mars by using war- surplus bombs.

*Impacts Impact – Objectification

Technological approaches toward solving environmental concerns lead to nature and human objectification. Ruth IRWIN Political Studies @ Auckland ‘8 “The Neoliberal State, Environmental Pragmatism, and its discontents” Environmental Politics 16: 4 p. 656-657 [Marcus]

Sandra Rosenthal and Rogene Buchholz also regard Pragmatism as the ‘radical correction of modernity’, however they seem to cope with the sceptical divide of nominalism slightly better than their co-authors. Their critique is that the modern scientific view objectifies nature and separates humanity from the natural world. Science is better understood as creative human activity, rather than the excavator of the essence of things. These are important ideas for confronting the belief that technology and science can sort out environmental problems (should they be so employed). Rosenthal and Buchholz emphasise a relational context, or organic unity, such that the individual is embedded in the locality. Biological creatures are continuous with nature, so there is no need for dualisms such as anthropocentricism/biocentrism, individual/holism, intrinsic/ instrumental and so on. They explain the rational and conscious organisation of experience to produce future value as a basis of Pragmatic ethics. Rationality and consciousness gets underlined here, to produce a ‘correctness’ of world view that only Pragmatism can provide (Rosenthal & Buchholz, in Light & Katz, 1996). Impact - Environment

An epistemological shift is necessary to solve environmental concerns. Ruth IRWIN Political Studies @ Auckland ‘8 “The Neoliberal State, Environmental Pragmatism, and its discontents” Environmental Politics 16: 4 p. 656-657 [Marcus]

If the environmentalist project is to generate action, then a genuine epistemological shift amongst the global population is required. The piecemeal pockets of revegetation, nature ‘enhancement’, isolated national parks, sustainable management, urban recycling and so on may only contribute very limited environmental ‘good’ and preserve narrow ecological niches, but at the same time, they contribute ideas towards a paradigm shift that normalises concern for ecology rather than the present atomised alienation of humanity from our surroundings. Impact – Radiation (Generic Colonization) Attempts to colonize space lead to radiation consequences on Earth. Peter Dickens Lecturer Sociology @ Cambridge, 10 Monthly Review, “The Humanization of the Cosmos—To What End?” 11/1/10, Volume 62, Issue 06 [Marcus]

Space colonization brings a number of other manufactured risks. The farther space vehicles penetrate the solar system, the more likely it is that they will be powered by nuclear, rather than solar, energy. It is not widely appreciated, for example, that the 1997 Cassini Mission to Saturn’s moons (via Jupiter and Venus) was powered by plutonium. One estimate is that if something had gone wrong while Cassini was still circling the earth, some thirty to forty million deaths could have occurred.22 No plans were in place for such an eventuality. Yet, as early as 1964, a plutonium-powered generator fell to earth, having failed to achieve orbit. Dr. John Gofman, professor of medical physics at the University of California, Berkeley, then argued that there was probably a direct link between that crash and an increase of lung cancer on Earth. Both President Obama and the Russian authorities are now arguing for generating electricity with plutonium in space, and building nuclear-propelled rockets for missions to Mars.23 Impact – Apocalypse Focus on climate change externalizes human relations and makes an apocalypse inevitable. Brian Wynne, Research Director of the Centre for the Study of Environmental Change (CSEC) at the University of Lancaster, 10 Theory, Culture, and Society, “Strange Weather, Again : Climate Science as Political Art, 2010, Volume 27 P. 289-306 [Marcus]

Passing these global issues pertaining to climate, but very far from only about climate and greenhouse gases, through the eye of the needle of GCMs and long-term climate simulation science has – with absolutely no deliberate intent so far as can be seen – produced its own global policy climate which externalizes the larger human-relational issues which contribute to the global apocalypse which is already upon us, regardless of what may happen to the climate. The moral discomforts which minority affluent world citizens feel when reminded of the grotesque poverty and desperate conditions of the majority distantly hint at this reality. Meanwhile rich-world politicians state that the only way that they can mobilize electoral support for even marginally progressive climate greenhouse gas policies is to have climate impact models which show such citizen-electors that their own self-interests are threatened, like sea-level rise inundating their local areas, or extreme weather events causing flooding to devastate their homes. Of course, self-interest will always be with us, and politics will always have to recognize its various manifestations. However, to act as if politics cannot change the moral and behavioural outlook of citizens, by identifying their more generous and relational human spirit and giving collective articulation, hope and public presence – and material policy form – to these elements of human nature, is timid, wrong, and maybe even selfdefeating in this domain. Elsewhere I have suggested that mainstream social science tends to reinforce an atomized and instrumental, rational choice self-interest model of the human subject, and while this is real for sure, it is not at all exhaustive (Wynne, 2007). Contrary dimensions of human subjectivity – intrinsically and ontologically as well as epistemically relational, responsible, and other-oriented – are also real, if also contingent. It can be seen as a responsibility of social science to bring out and encourage these realities, in a manner which is anyway unavoidably interventionist. A severe problem for this more complex and contingent, emergentrealist constructivist programme in social science is that in those many domains, such as climate, where social and human issues are interwoven with scientific-technical ones, the dominant prevailing scientific knowledge already carries tacit imaginations of human and social actors and capacities, and also (usually by default, without deliberate intent) imposes ‘the’ public meaning on the situation and its actors. These imaginaries are strongly normative, and they are typically instrumental, self-interest only visions, as with neo-classical economistic ideologies. Of course these cannot be blamed on climate science; but they do mutually reinforce themselves, in an implicit model of the science-policy order. Impact – Ethics Pro-space advocates project ideologies of Western dominance into space. The elitist narcissistic perspective of the affirmative negates ethical relations with others.

Peter DICKENS Lecturer Sociology @ Cambridge AND James ORMROD “Outer Space and Internal Nature: Towards a Sociology of the Universe” Sociology 41 (4) p. 615-618

Some preliminary indications of an extreme form of this kind of self come from an ethnographic study of citizens actively promoting and advocating the extension of society into space (Ormrod, 2006). There is a ‘pro-space’ social movement, largely operating out of the USA, numbering approximately 100–150,000 members. These activists (many from the quasi-technical new middle class identified at the heart of the culture of narcissism [Sennett, 1974]) are paid- up members of one or more pro-space organizations, who meet to discuss the science and technology necessary to explore, develop and colonize the universe, as well as lobbying politicians in favour of both public and private programs aimed at accomplishing this. We now draw upon our research into the movement, not as conclusive proof of a general condition of narcissism, but merely as illustrations of how some individuals relate to the universe.1 There are strong indications that these pro-space activists are amongst those most affected by late modern narcissism. Early on in life, these activists come to project infantile unconscious phantasies (those relating to omnipotence and fusion with the infant’s ‘universe’) into conscious fantasies2 about exploring and developing space, which increasingly seem a possibility and which now achieve legitimacy largely through the ideology of the libertarian right. Those who have grown up in the ‘post-Sputnik’ era and were exposed at an early date to science fiction are particularly likely to engage in fantasies or daydreams about travelling in space, owning it, occupying it, consuming it and bringing it under personal control. Advocates talk about fantasies of bouncing up and down on the moon or playing golf on it, of mining asteroids or setting up their own colonies. These fantasies serve to protect the unconscious phantasy that they are still in the stage of infantile narcissism. Of course not all of those people growing up in late modern societies come to fantasize about space at such an early age like this, and are less single minded in their attempts to control and consume the universe, but we argue that this is nonetheless the way in which some dominant sectors of Western society relate to the universe. It is not only pro-space activists, but many well-to-do businesspeople and celebrities who are lining up to take advantage of new commercial opportunities to explore space as tourists. The promise of power over the whole universe is therefore the latest stage in the escalation of the narcissistic personality. A new kind of ‘universal man’ is in the making. Space travel and possible occupation of other planets further inflates people’s sense of omnipotence. Fromm (1976) discusses how in Western societies people experience the world (or indeed the universe) through the ‘having’ mode, whereby individuals cannot simply appreciate the things around them, but must own and consume them. For the narcissistic pro-space activist, this sentiment means that they feel a desperate need to bring the distant objects of outer space under their control: Some people will look up at the full moon and they’ll think about the beauty of it and the romance and history and whatever. I’ll think of some of those too but the primary thing on my mind is gee I wonder what it looks like up there in that particular area, gee I’d love to see that myself. I don’t want to look at it up there, I want to walk on it. (25-year-old engineering graduate interviewed at ProSpace March Storm 2004) Omnipotent daydreaming of this kind is also closely linked to the idea of regaining a sense of wholeness and integration once experienced with the mother (or ‘monad’) in the stage of primary narcissism, counterposed to a society that is fragmenting and alienating. Experiencing weightlessness and seeing the Earth from space are other common fantasies. Both represent power, the ability to ‘break the bonds of gravity’, consuming the image of the Earth (Ingold, 1993; Szersynski and Urry, 2006) or ‘possessing’ it through gazing at it (Berger, 1972). They also represent a return to unity. Weightlessness represents the freedom from restraint experienced in pre-oedipal childhood, and perhaps even a return to the womb (Bainbridge, 1976: 255). Seeing the Earth from space is an experience in which the observer witnesses a world without borders. This experience has been dubbed ‘the overview effect’ based on the reported life-changing experiences of astronauts (see White, 1987). Humans’ sense of power in the universe means our experience of the cosmos and our selves is fundamentally changing: It really presents a different perspective on your life when you can think that you can actually throw yourself into another activity and transform it, and when we have a day when we look out in the sky and we see lights on the moon, something like that or you think that I know a friend who’s on the other side of the Sun right now. You know, it just changes the nature of looking at the sky too. (46-year-old space scientist interviewed at ProSpace March Storm 2004) In the future, this form of subjectivity may well characterize more and more of Western society. A widespread cosmic narcissism of this kind might appear to have an almost spiritual nature, but the cosmic spirituality we are witnessing here is not about becoming immortal in the purity of the heavens. Rather, it is spirituality taking the form of self-worship; further aggrandizing the atomized, self-seeking, 21st-century individual (see Heelas, 1996). Indeed, the pro-space activists we interviewed are usually opposed to those who would keep outer space uncontaminated, a couple suggesting we need to confront the pre-Copernican idea of a corrupt Earth and ideal ‘Heaven’. For these cosmic narcissists, the universe is very much experienced as an object; something to be conquered, controlled and consumed as a reflection of the powers of the self. This vision is no different to the Baconian assumptions about the relationship between man and nature on Earth. This kind of thinking has its roots in Anaxagoras’ theory of a material and infinite universe, and was extended by theorists from Copernicus, through Kepler and Galileo to Newton. The idea that the universe orients around the self was quashed by Copernicus as he showed the Earth was not at the centre of the universe and that therefore neither were we (Freud, 1973: 326). However, science has offered us the promise that we can still understand and control it. Robert Zubrin, founder of the Mars Society, trumpets Kepler’s role in developing the omniscient fantasy of science (it was Kepler who first calculated the elliptical orbits of the planets around the Sun): Kepler did not describe a model of the universe that was merely appealing – he was investigating a universe whose causal relationships could be understood in terms of a nature knowable to man. In so doing, Kepler catapulted the status of humanity in the universe. Though no longer residing at the centre of the cosmos, humanity, Kepler showed, could comprehend it. Therefore […] not only was the universe within man’s intellectual reach, it was, in principle, within physical reach as well. (Zubrin with Wagner, 1996: 24) Thus Zubrin begins to lay out his plan to colonize Mars. The Universe as Object for the Exercise of Power While pro-space activists and others are daydreaming about fantastical and yet seemingly benign things to do in outer space, socially and militarily dominant institutions are actively rationalizing, humanizing and commodifying outer space for real, material, ends. The cosmos is being used as a way of extending economic empires on Earth and monitoring those individuals who are excluded from this mission. On a day-to-day level, communications satellites are being used to promote predominantly ‘Western’ cultures and ways of life. They also enable the vast capital flows so crucial to the global capitalist economy. Since the 1950s, outer space has been envisaged as ‘the new high ground’ for the worldwide exercise of military power. The ‘weaponization of space’ has been proceeding rapidly as part of the so-called ‘War on Terror’ (Langley, 2004). The American military, heavily lobbied by corporations such as Lockheed Martin, Raytheon and Boeing, is now making new ‘Star Wars’ systems. These have been under development for over 30 years but are now being adapted to root out and destroy ‘terrorists’, if necessary with the aid of ‘smart’ nuclear weapons. American government spending on the Missile Defence Program jumped by 22 percent in 2004, reaching the huge sum of $8.3 billion (Langley, 2004). The unreal and almost certainly unobtainable objective is to create a new kind of ‘pure war’ in which terrorists are surgically pinpointed and killed while local civilians remain uninjured (Virilio, 1998; Virilio and Lotringer, 1998). Meanwhile, and paralleling the weaponization of space, surveillance satellites have also been much enhanced. Although originally developed for military purposes, they are now increasingly deployed to monitor nonmilitary populations, creating a global, orbital panopticon. Workers in British warehouses are even being tagged and monitored by satellite to ensure maximum productivity (Hencke, 2005). For those elites in positions of power over the universe, as for pro-space activists, the universe is experienced as an object to be placed in the service of human wants and desires. However, for those with less privileged access to the heavens, the universe is far from being such an object – their relationship with it is more fearful and alienated than ever before. Alt – Paradigm Shift

Our alternative avoids their one-size fits all. Only a paradigm shift in our social relationship to renewables activates their critical capacity.

John BYRNE Center for Energy & Environmental Policy, University of Delaware ET AL ‘9 “Relocating Energy in the Social Commons” Bulletin of Science,Technology & Society 29 (2) p. 87-88

Paradigm Shift Shedding the institutions that created the prospect of climate change will not happen on the watch of the green titans or extra large nuclear power. The modern cornucopian political economy fueled by abundant, carbon-free energy machines will, in fact, risk the possibility of climate change continually because of the core properties of the modern institutional design. Although the abundant energy machine originated and matured in the United States and industrial Europe, the logic of unending growth built into the modern model has promoted its global spread. Today, both extra- large nuclear power and industrial-scale renewables are at the forefront of the trillion dollar clean energy technology development and transfer process envisioned for the globe (International Energy Agency, 2006). Nuclear energy is seen as offering unlimited potential for rapid development in India and China, while large-scale renewables seamlessly fit into existing international financial aid schemes. A burgeoning renewables industry boasts economic opportunities in standardization and certification for delivering green titans to developing countries. If institutional change is to occur, if energy-society relations are to be transformed, and if the threat of global warming is to be earnestly addressed, we will have to design and experiment with alternatives other than these. Given the global character of the challenge, cookie cutter counter-strategies are certain to fail. Often, outside the box alternatives may not be sensible in the modern context. Like a paradigm shift, we need ideas, and actions guided by them, which fail in one context (here, specifically, the context of energy obesity) in order hopefully to support the appearance of a new context. The concept and practice of a sustainable energy utility is offered in this spirit.11 The sustainable energy utility (SEU) involves the creation of an institution with the explicit purpose of enabling communities to reduce and eventually eliminate use of obese energy resources and reliance on obese energy organizations. It is formed as a nonprofit organization to support commons energy development and management. Unlike its for-profit contemporaries, it has no financial or other interest in commodification of energy, ecological, or social relations; its success lies wholly in the creation of shared benefits and responsibilities. The SEU is not a panacea nor is it a blueprint for fixing our energy-carbon problems. It is a strategy to change energy-ecology-society relations. It may not work, but we believe it is worth the effort to invent and pursue the possibility. There should be little doubt about the difficulty of the task. Regimes develop through the interplay of technology and society over time, rather than through prescribed programs. They alter history and then seek to prevent its change, except in ways that bolster regime power. Of specific importance here, obese utilities will not simply cede political and economic success to an antithetical institution—the SEU. That is why change is so hard to realize. Shifting a society towards a new energy regime requires diverse actors working in tandem, across all areas of regime influence. Economic models, political will, social norm development, all these things must be shifted, rather than pulled, from the current paradigm. The SEU constructs energy–ecology-society relations as phenomena of a commons governance regime. It explicitly reframes the preeminent obese energy regime organization—the energy utility—in the antithetical context of using less energy. And, when energy use is needed, it relies on renewable sources available to and therefore governable by the community of users (rather than the titan technology approach of governance by producers). In contrast to the cornucopian strategy of expanding inputs in an effort to endlessly feed the obese regime, the SEU focuses on techniques and social arrangements which can serve the aims of sustainability and equity. It combines political and economic change for the purpose of building a postmodern energy commons; that is, a form of political economy that relies on commons, rather than commodity, relations for its evolution. Specifically, it uses the ideas of a commonwealth economy and a community trust to achieve the goal of postmodern energy sustainability. The meanings of commonwealth, community trust, and commons, relevant to a SEU, are explored below.

*Alternatives Alt - Discourse

Fearful representations of climate change are ineffective at changing public mindset – we must use non-threatening discourse to induce real change O’Neill and Nicholson-Cole 09, Researches Social dimensions of Climate change at the Tyndall Centre for Climate change research. “Fear won’t do it: Promoting positive engagement with climate change through visual and iconic representations” [http://scx.sagepub.com/content/early/2009/01/07/1075547008329201.full.pdf+html] Fear-inducing representations of climate change are widely employed in the public domain. However, there is a lack of clarity in the literature about the impacts that fearful messages in climate change communications have on people’s senses of engagement with the issue and associated implications for public engagement strategies. Some literature suggests that using fearful representations of climate change may be counterproductive. The authors explore this assertion in the context of two empirical studies that investigated the role of visual, and iconic, representations of climate change for public engagement respectively. Results demonstrate that although such representations have much potential for attracting people’s attention to climate change, fear is generally an ineffective tool for motivating genuine personal engagement. Nonthreatening imagery and icons that link to individuals’ everyday emotions and concerns in the context of this macro-environmental issue tend to be the most engaging. Recommendations for constructively engaging individuals with climate change are given. Alt – Social Justice The alternative is to reject unilateral action in space while embracing social justice. Peter DICKENS Lecturer Sociology @ Cambridge AND James ORMROD, Lecturer in sociology at University of Brighton, 07 “Outer Space and Internal Nature: Towards a Sociology of the Universe” Sociology 41 (4) p. 615-618 [Marcus]

Society’s relations with the cosmos are now at a tipping point. The cosmos could be explored and used for primarily humanitarian ends and needs. Satellites could continue to be increasingly used to promote environmental sustainability and social justice. They can for example be, and indeed are being, used to track the movements of needy refugees and monitor environmental degradation with a view to its regulation (United Nations, 2003). But if this model of human interaction is to win out over the use of the universe to serve dominant military, political and economic ends then new visionaries of a human relationship with the universe are needed. In philosophical opposition to the majority of pro-space activists (though they rarely clash in reality) are a growing number of social movement organizations and networks established to contest human activity in space, including the military use of space, commercialization of space, the use of nuclear power in space and creation of space debris. Groups like the Global Network Against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space and the Institute for Cooperation in Space are at the centre of this movement. The activities and arguments of these groups, to which we are by and large sympathetic, demonstrate the ways in which our understanding and use of outer space are contested in pivotal times. Floating Pic Only in a world of the Alt can space be successfully developed. Peter Dickens Lecturer Sociology @ Cambridge, 10 Monthly Review, “The Humanization of the Cosmos—To What End?” 11/1/10, Volume 62, Issue 06 [Marcus]

Instead of indulging in over-optimistic and fantastic visions, we should take a longer, harder, and more critical look at what is happening and what is likely to happen. We can then begin taking a more measured view of space humanization, and start developing more progressive alternatives. At this point, we must return to the deeper, underlying processes which are at the heart of the capitalist economy and society, and which are generating this demand for expansion into outer space. Although the humanization of the cosmos is clearly a new and exotic development, the social relationships and mechanisms underlying space-humanization are very familiar. A2: Alt Does Nothing Our alternative doesn’t mean inaction—it means careful thinking about how and why we act.

Ruth IRWIN Political Studies @ Auckland ‘8 “The Neoliberal State, Environmental Pragmatism, and its discontents” Environmental Politics 16: 4 p. 653-654

Light argues that the antagonism towards anthropocentricism is so pervasive in environmental ethics it has become dogma. His complaint is that theories about the environment based on non-anthropocentric values (or non- Utilitarian values) are mere ‘intramural’ word-play. They do not ground the actions of most environmental activists. Instead, using the example of the Amazon Rainforest, Light notes that the environmentalist Chico Mendes was motivated to protect the Rainforest because it was the livelihood of his entire community. Light looks to American Pragmatism to sort out the theory versus practice debate. The many different theoretical approaches in environmental ethics, whether they be anthropocentric or non-anthropocentric, all seem to end up in a practical ‘convergence’ which tends towards protecting or creating ecological habitats. Bryan Norton developed this theory of ‘convergence’, arguing that in the end, if taken in their ‘pure’ form, both anthropocentric and ecocentric environmentalisms would eventually turn up the same policy results (Norton, 2005: 508). So, even the animal rights theorists such as Singer will prudently advise the humane hunting of exogenous rabbits, for example, for the larger good of the Australian Outback. While I sympathise with the desire for urgent and practical action, I do not think careful thinking requires postponing all environmental care. It is naive and even dangerous to relegate the myriad debates about Utilitarian versus intrinsic value, or anthropocentric versus non-anthropocentric, or individualist versus community aims, and even monad versus pluralist beliefs, to a ‘ convergent’ interest in environmental protection. Norton believes that nonanthropocentric ethics will turn out to converge with anthropocentric ethics because in the end both are politically contested by humans (Norton, 2005: 508). While I think his point that political dualism may collapse towards the same ends, the notion of a mature political convergence, or dialectical synthesis is not necessarily going to be the case. Clearly not all political views are interested in environmental protection. Some interest groups claim to be environmentally motivated, such as big business including ‘sustainability’ in their mission statements and advertising without any genuine attempt to alter capitalist practices in a far-reaching way. Conflicting strategies produce divergent politics that play out in the practices of activists, politicians, citizens and schoolteachers. Theoretical premises affect the organising paradigms, selfunderstanding and the actions of societies, communities, and individuals. In a global world, anthropocentric capitalism dominates the ‘view’ that the media, advertising, education, work ethic, consumerism and so forth take on the environment. As Heidegger cogently argues, everything in the modern world is enframed and understood as potential resource. So thinking our way out of these conundrums is vitally important, in both the short and long term, for realigning the relationship that humanity as a whole has with the earth in all its aspects. Diverging ideas about how the relationship between humanity and the earth can be best cared for is a constructive way forward (and impossible to annihilate) because different contexts generate different relationships. Thought is like biodiversity; difference shelters contingent possibilities for unexpected problems, monoculture fails when confronted with new disease, or new weather conditions, new predators, new constraints, and new conditions of possibility.

*Representations Reps 1 st

Mindset shift is a prerequisite to learning about climate change. Brian Wynne, Research Director of the Centre for the Study of Environmental Change (CSEC) at the University of Lancaster, 10 Theory, Culture, and Society, “Strange Weather, Again : Climate Science as Political Art, 2010, Volume 27 P. 289-306 [Marcus]

While the political controversies invested in global climate science have raged back and forth, over whether human-induced climate change is real and threatening or not, a different perspective on this question of the social construction of scientific knowledge and meaning has been largely ignored. This is whether IPCC as the key scientific authority here may have understated the risks, and may also have in effect obscured the crucial commonsense question of error costs. The furore generated on the eve of the December 2009 Copenhagen climate summit by the leaked emails from the University of East Anglia (UEA) Climate Research Unit, a leading global scientific IPCC contributor, was effectively a tale of ‘social construction means error and falsehood’ – either incompetence or dishonesty, or both, as social explanations of that falsehood. However, a less superficial examination when science is facing such hideous natural and social system complexities indicates (a) that whatever human failings prevailed in the specific language and perhaps practice of the UEA scientists, the forms of validation of IPCC scientific conclusions and judgements are far more substantial, multi-dimensional and robust than can be seriously damaged by one such allegedly illegitimate specific instance; and (b) the dominant institutional social construction of the scientific knowledge and its meaning for policy can be seen to have been operating in the opposite sense to that of falsification and denial – in other words, to have constructed a representation of future climate change and its human causes which presents it as reassuringly gradual: in terms of rate and scale, within the bounds of policy manageability using existing cultural habits and institutional instruments; and requiring no more radical re-thinking of, for example, the powerful normatively-weighted cultural narratives of capitalist consumer modernity and its self-affirming (and other-excluding) particular and parochial imaginaries of ‘progress’, rationality, policy and knowledge. Thus, for example, when Simon Shackley and I were researching climate modelling in the 1990s, we conducted ethnographic research at the UK Hadley Centre for Climate Modelling and Prediction, and in addition interviewed leading IPCC scientists, there and internationally.

**NEG A2: Perm Turn: the permutation is more of the same, not pragmatic learning. Harnessing renewables into the dominant system appropriates environmental and atmospheric commons for imperialism.

John BYRNE Center for Energy & Environmental Policy, University of Delaware ET AL ‘9 “Relocating Energy in the Social Commons” Bulletin of Science,Technology & Society 29 (2) p. 86-87

A final problem specific to an extra-large green energy project is the distinctive environmental alienation it can produce. The march of commodification is spurred by the green titans as they seek to enter historic commons areas such as mountain passes, pasture lands, coastal areas, and the oceans, in order to collect renewable energy. Although it is not possible to formally privatize the wind or solar radiation (for example), the extensive technological lattices created to harvest renewable energy on a grand scale functionally preempt commons management of these resources.10 Previous efforts to harness the kinetic energy of flowing waters should have taught the designers of the mega-green energy program and their environmental allies that environmental and social effects will be massive and will preempt commons-based, society-nature relations. Instead of learning this lesson, the technophilic awe that inspired earlier energy obesity now emboldens efforts to tame the winds, waters, and sunlight— the final frontiers of he society-nature commons—all to serve the revised modern ideal of endless, but low- to no- carbon emitting, economic growth. Their permutation creates theoretical monoculture. It cultivates attention only to the immediate and ignores the importance of theoretical frameworks for approaching environmental issues.

*A2s A2: Eco-Prag Turn: eco-pragmatism is anti-practical—it only caters to the american middle class. voting negative is the only way to ensure that critical questions about global equity and imperialism get priority.

Ruth IRWIN Political Studies @ Auckland ‘8 “The Neoliberal State, Environmental Pragmatism, and its discontents” Environmental Politics 16: 4 p. 656-657

Light is intrigued by the need to ‘convince people’ to pursue environmental ends. Unfortunately this is the only element of interest in his essay, ‘The case for a practical pluralism’, which is a superficial skate over what is for him familiar terrain. He does little to explain the various forms of pluralism apparently advocated by the authors he surveys. He blithely avoids any engagement with ‘deconstructive poststructuralist differance’ (Light, 2002b: 15) by naming and shaming it as moral relativism. Relativism entails abandoning the view that there are some moral stances better than others that could guide our ethical claims about how we should treat nature. If we admit relativism then, one could argue, we would give up on attempts to form a moral response to the cultural justifications put forward to defend the abuse or destruction of other animals, species or ecosystems. Relativism entails that ethics is relative to different cultural traditions. (Light, 2002b: 7) Light maintains a North American faith in the ‘normative force’ of American cultural superiority. This criticism of relativism neglects the emphasis on critique, where evaluation based on mutual respect for differing viewpoints can still come to an ethical decision – but quite possibly not a consensus. ‘Pragmatic’ resignation to Western prejudice avoids the hard ‘development’ questions about uneven global wealth distribution, skewed global economic and environmental policy. Avoiding theory results in ignoring the absorption of old liberal and more recent environmental terms, such as ‘choice’, ‘freedom’, ‘equality’, ‘sustainability’ into the neoliberal lexicon and its resultant policy initiatives that are being implemented in nations around the planet. Ignoring theory is to ignore what is actually going on. A2: Convincing People Key We have an oppoturnity for a sea-change that voting affirmative quashes. Voting negative builds a positive radical vision instead of their conservative pessimism.

Ruth IRWIN Political Studies @ Auckland ‘8 “The Neoliberal State, Environmental Pragmatism, and its discontents” Environmental Politics 16: 4 p. 656-657

Misgivings aside, it is effectively the educational project that engages Light. I agree that ‘convincing people’ is central to the protection of the environment. But it is important not to underestimate the potential for human society to change. Light’s pluralism is based on a despondent view that the American status quo is insurmountable: ‘when possible we should work within the traditional moral psychologies and ethical theories that most people already have and direct them, where we can, at the same environmental ends’ (Light, 2002b: 15). This social conservatism is combined with a very modern sense of urgency – an urgency to avert impending doom immediately. ‘Given the environmental crisis we face, how could we afford the sorts of delays seemingly implicit in such talk of ‘‘cultural experiments’’?’ (Light, 2002a: 7). This feeling of crisis dominated popular psychology of environmental books in the late 1980s. Books like James Lovelock’s (1979) Gaia Hypothesis, Schumacher’s (1973) Small is Beautiful and many others gave voice to the widespread misgivings of the Cold War’s nuclear proliferation, together with growing but largely disbelieved body of evidence about global warming. At the same time, the realisation that fossil fuels might become exhausted, Ehrlich’s exponential population estimates, and mounting numbers of species extinctions and habitat destruction contributes to the discourse of crisis. By now the majority of people in every nation have become somewhat familiar with the discourse of environmental crisis. I think Light underestimates the significance of this familiarity. The general acceptance that there is a massive, global, environmental problem is providing the conditions for a ‘ sea change’ in the ways humanity interacts with the earth. If we are merely pragmatic and remain with the traditional common sense ideas, then we will not be ‘urgently’ helping environmental protection and enhancement to take place. We will be inhibiting the potential for a dramatic and irreversible change, a recognition of the anomalies not described by the modern, Idealist view of nature, an epistemological shift, for which the world is increasingly ready. A2: Predictions Good Climate should be viewed in the realm of objective truths, not predictive claims. Brian Wynne, Research Director of the Centre for the Study of Environmental Change (CSEC) at the University of Lancaster, 10 Theory, Culture, and Society, “Strange Weather, Again : Climate Science as Political Art, 2010, Volume 27 P. 289-306 [Marcus]