FPIN Journal Club RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL SPEAKER NOTES

Title: Should you bypass anticoagulant “bridging” before and after surgery? Author: Kate Rowland PURL Citation: Jarrett, J, Schaffer, T, Rowland, K. PURLs: Should you bypass anticoagulant "bridging" before and after surgery? J Fam Pract. 2015 Dec;64(12):794-800. Original Article: Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Kaatz S, et al. Perioperative bridging anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:823-833.

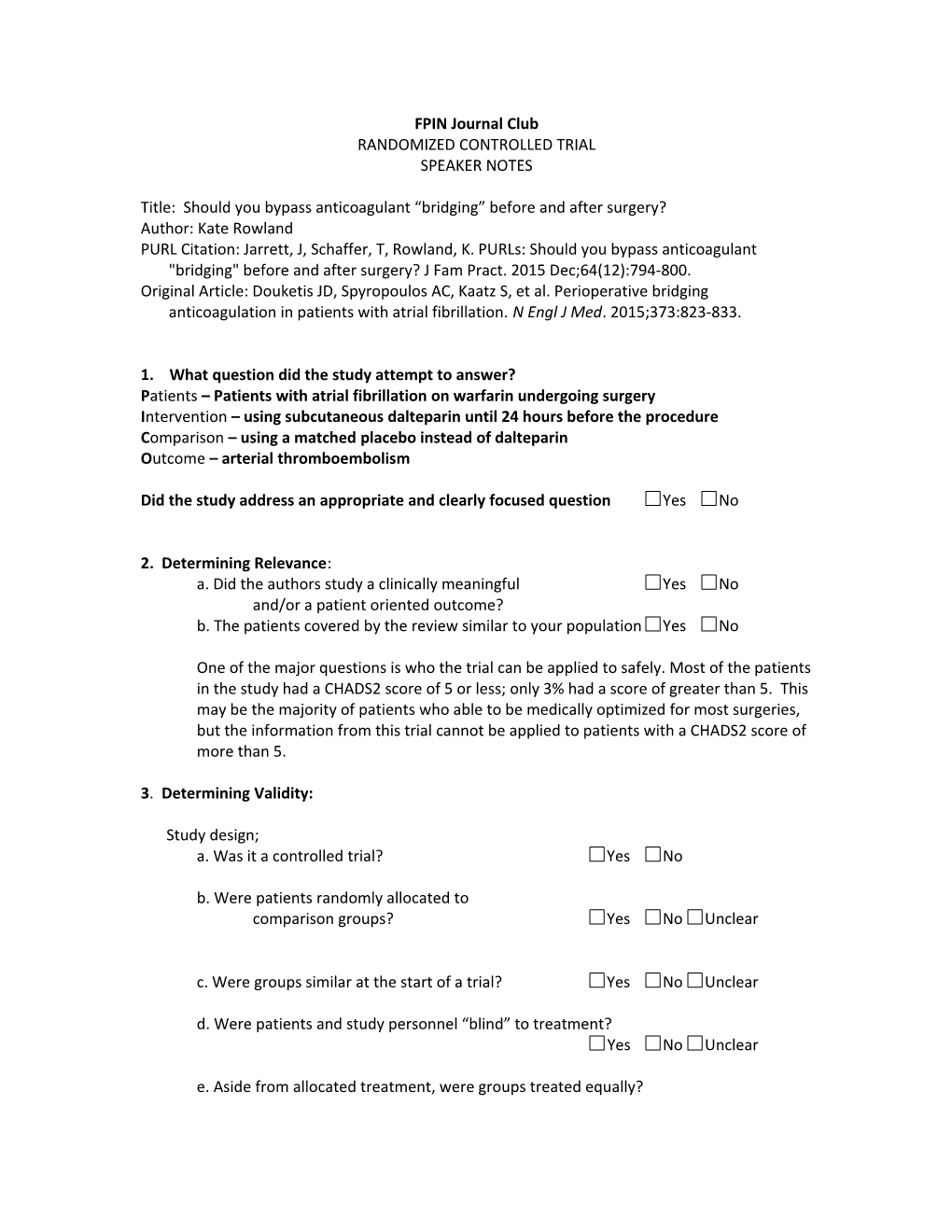

1. What question did the study attempt to answer? Patients – Patients with atrial fibrillation on warfarin undergoing surgery Intervention – using subcutaneous dalteparin until 24 hours before the procedure Comparison – using a matched placebo instead of dalteparin Outcome – arterial thromboembolism

Did the study address an appropriate and clearly focused question Yes No

2. Determining Relevance: a. Did the authors study a clinically meaningful Yes No and/or a patient oriented outcome? b. The patients covered by the review similar to your population Yes No

One of the major questions is who the trial can be applied to safely. Most of the patients in the study had a CHADS2 score of 5 or less; only 3% had a score of greater than 5. This may be the majority of patients who able to be medically optimized for most surgeries, but the information from this trial cannot be applied to patients with a CHADS2 score of more than 5.

3. Determining Validity:

Study design; a. Was it a controlled trial? Yes No

b. Were patients randomly allocated to comparison groups? Yes No Unclear

c. Were groups similar at the start of a trial? Yes No Unclear

d. Were patients and study personnel “blind” to treatment? Yes No Unclear

e. Aside from allocated treatment, were groups treated equally? Yes No Unclear

f. Were all patients who entered the trial properly accounted for at its conclusion? Yes No Unclear

4. What are the results? a. What are the overall results of the study?

There were 4 arterial thromboembolism events (ATE) in the group that received no bridging and 3 in the group that received the dalteparin bridge. This was non-inferior and had a p=0.71 for superiority. Major bleeding occurred in 1.3% of the no- bridge group and 3.2% of the bridge group (p=0.005), suggesting a risk of harm.

b. Are the results statistically significant? Yes No c. Are the results clinically significant? Yes No d. Were there other factors that might have affected the outcome? Yes No

5. Applying the evidence: a. If the findings are valid and relevant, will this change your current practice? Yes No b. Is the change in practice something that can be done in a medical care setting of a family physician? Yes No c. Can the results be implemented? Yes No d. Are there any barrier to immediate implementation? Yes No e. How was this study funded? Funded by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute 6. Teaching Points

Considerations for implementation:

This study demonstrates one of the paradoxes of the medical literature: When an intervention that should make sense in theory does not make a difference in actual practice. It’s reasonable to think that, when you hold warfarin in a patient already predisposed to a thromboembolic event, the patient would experience higher risk for thromboembolism. Because this intuitively makes sense, we have always “bridged” anticoagulant therapy in patients when we need to hold their warfarin perioperatively. However, this study demonstrates that using a placebo anticoagulant is not inferior at preventing arterial thromboembolism. Out of 1800 patients, there were 3 arterial thromboembolic events in the group that received the dalteparin bridge and 4 arterial thromboembolic events in the group that received a placebo bridge.

Not only did the patients experience the same risk of thromboembolism, the patients who received the active bridge with dalteparin had a significantly higher risk of major bleeding, which was defined very specifically in the article is things such as bleeding requiring transfusion or hospitalization, or drop in hemoglobin of more than 2 points. This also intuitively makes sense, but we have always thought that the risk of bleeding was outweighed by the decrease in risk of thromboembolism.

Studies like these can be complicated when it comes to implementing them into practice. Because they don’t intuitively makes sense, it can be difficult to overcome the barrier of “common sense” when we are actually putting in orders perioperatively. It still makes sense that giving an anticoagulant will reduce the risk of thrombosis, even if that does not seem to be the case when studied scientifically. In fact, if this study is not applied appropriately, we will be doing harm to our patients by increasing the risk of bleeding without conferring any benefit.

It seems the right thing to do is to stop the warfarin 5 days before the surgery, and not provide any bridging dalteparin or enoxaparin. The warfarin should be started again, in the absence of any contraindication or overt bleeding, within 12-24 hours after a low risk surgery and 48-72 hours after a high risk surgery.

Another complicated point of implementation for this study is carefully choosing the patient population that applies to. As mentioned above, the patients included in the study largely had a CHADS2 score of less than or equal to 5. The results of the study cannot be applied to a patient with a CHADS2 score greater than 5 (6 or above). It may be that they have exactly the same result, but this study did not include enough of them to draw any conclusions about these patients.