TECHNICAL NOTES

______U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION SERVICE BIOLOGY – 23 OLYMPIA, WASHINGTON MAY 2003

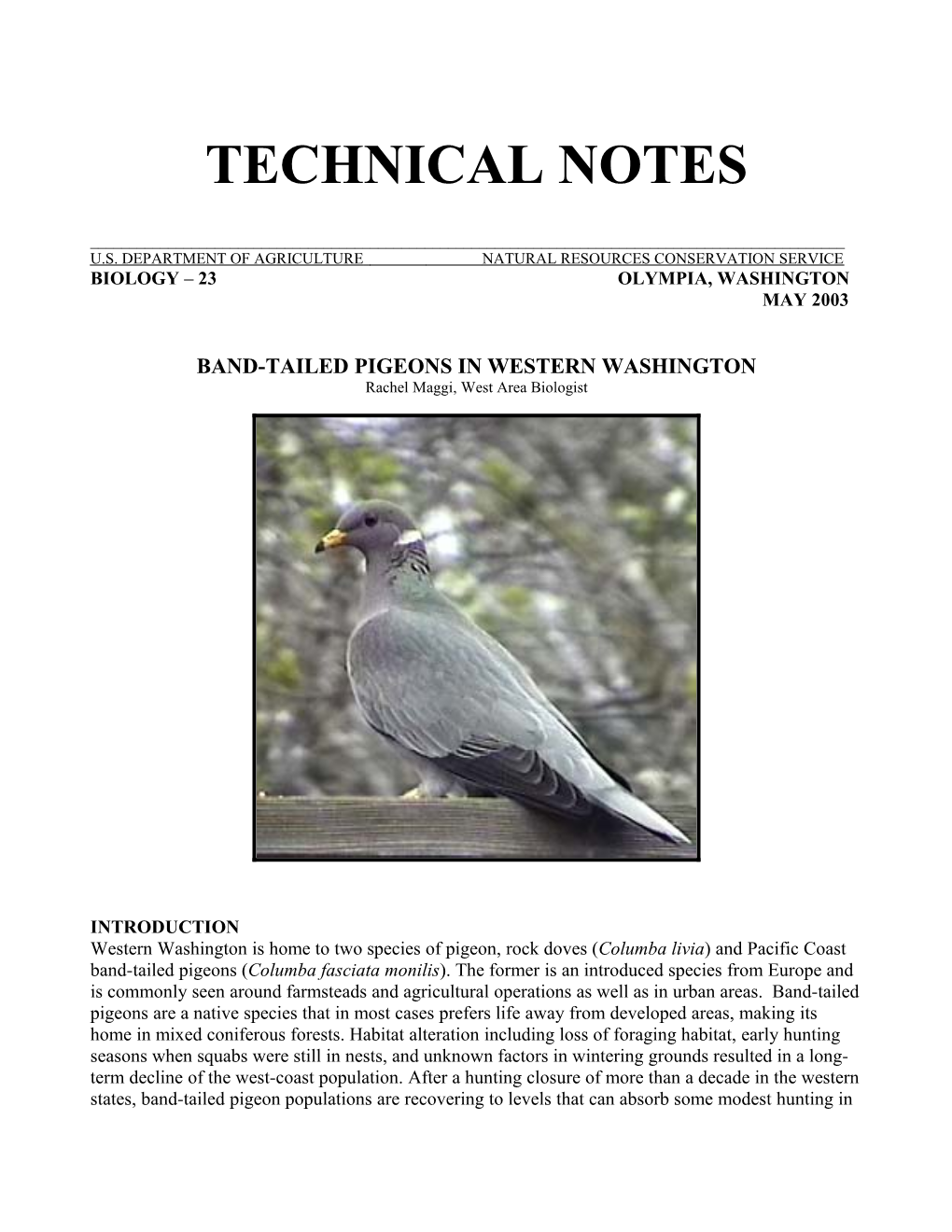

BAND-TAILED PIGEONS IN WESTERN WASHINGTON Rachel Maggi, West Area Biologist

INTRODUCTION Western Washington is home to two species of pigeon, rock doves (Columba livia) and Pacific Coast band-tailed pigeons (Columba fasciata monilis). The former is an introduced species from Europe and is commonly seen around farmsteads and agricultural operations as well as in urban areas. Band-tailed pigeons are a native species that in most cases prefers life away from developed areas, making its home in mixed coniferous forests. Habitat alteration including loss of foraging habitat, early hunting seasons when squabs were still in nests, and unknown factors in wintering grounds resulted in a long- term decline of the west-coast population. After a hunting closure of more than a decade in the western states, band-tailed pigeon populations are recovering to levels that can absorb some modest hunting in modified seasons. Much work needs to be done in the realm of habitat protection, enhancement, and creation to assure the recovery continues. By restoring and enhancing forested areas used by band-tails, landowners will also be improving habitat characteristics favored by a variety of other forest wildlife species.

DESCRIPTION Standing at 14-15 ½ inches, band-tails are slightly larger than the common rock dove. The head and upper body of the bird is gray in color, with its underside grading from darker purplish-gray at the top of the breast, to near white at the tail. A black band is present across the tail feathers. Adult birds have a thin white band on the back of the neck feathers with several rows of iridescent green and purple feathers below it. The bill and feet are yellow with black tips. Male and female birds are similar in appearance. (Audubon, 1995)

RANGE Band-tailed pigeons are found in two distinct populations: one in the intermountain west with nesting from Wyoming southward and the other associated with the Pacific coast with breeding from southeastern Alaska south to Baja, California. In Washington the birds range only West of the Cascade Mountains. (Lewis et al, 2003) The majority of Washington’s birds winter from south of Redding, California through Mexico (Schroeder and Braun, 1993). Research in Oregon revealed that some birds live year round in the Pacific Northwest (Jarvis and Passmore, 1992).

LIFE HISTORY Band-tailed pigeons return to Western Washington during their breeding season (April-September) and feed heavily on the fruits of the plants listed in Table 1. (Lewis et al., 2003). Females build a loose platform nest in the fork of conifer or deciduous tree branches, typically 6-30 feet off the ground. Nesting material provided by the male is often small to medium sized twigs. One egg is laid per nesting cycle, with pairs undertaking 2-3 cycles per nesting season in most years. Both sexes share incubation responsibility. The squabs hatch within 18-20 days, and leave the nest within 30 days of hatching. (Ehrlich, et. al. 1988) The majority of nesting in Washington occurs in areas below 1000 feet in elevation.

Blue Elderberry Sambucus cerulea var. cerulea HABITAT In Washington, band-tails are most often found associated with forested habitats that are in close proximity (12-15 miles) to mineral springs, although some pigeons have been documented flying more than 50 miles each way to favored foraging sites (J. Bottorff, Washington Department of Natural Resources, personal communication, Sanders, 2000). Pigeons forage in upland forests, riparian areas, edge habitat between open farm fields and forest, and occasionally forested urban areas. High quality pigeon habitat has high species diversity in both the overstory and understory. Forests containing large numbers of mast (nuts, berries or fruits) producing trees and shrubs are preferred since they make up the majority of the birds’ diet. This is especially critical during the summer nesting season and early fall migration periods. Some food items that are most commonly consumed during the nesting and early migration season are listed in Table 1 below. The primary forage species listed in the table are of particular importance due to their high nutritive qualities, broad distribution, and availability. Band-tails will also make use of waste grain left over from fall harvest (Jarvis and Passmore, 1992) as well as other domestic plants like holly and cherries. Nesting habitat is another key component in favorable band- tailed pigeon habitat. Western Oregon birds were found to prefer Red Elderberry Sambucus racemosa closed-canopy, conifer forests with trees that are 3-10 inch dbh or 5-20 years old (Leonard, 1998).

Mineral springs are critical to band-tail pigeons because they provide mineral salts such as calcium needed for egg production. The salts are also necessary for one of the birds most peculiar adaptations, their ability to produce “crop milk” for their squabs (chicks). Adults produce this milky substance in their crops, which is then fed to their young during the first few weeks of the nestling’s life. Known mineral spring sites in Western Washington are limited. Most are found along marine shorelines and hillside slopes but several are documented in inland locations. Vegetative structure around the springs is also a key habitat component. Birds prefer tall, sturdy trees to land and perch on but have trouble

Cascara Rhamnus purshiana navigating through dense shrubbery (such as non-native blackberry and scotchbroom) located near the spring. (Pacific Flyway Council, 2001, Lewis et al., 2003)

Table 1-Preferred Native Food Plants of Band-tailed Pigeons in Western Washington Common name Scientific name Fruit Fruiting Time PRIMARY Cascara Rhamnus purshiana Yellow to red August- berries, ripening September to black Red Elderberry Sambucus racemosa Bright red May-July berries Blue Elderberry Sambucus cerulea var. Blue to blue- August- cerulea black berries September SECONDARY Wild Cherry Prunus sp. Red, purple or June-July black Salal Gaultheria shallon Reddish blue- August- dark purple September berries Serviceberry Amelanchier alnifolia Purple berries August- September Madrone Arbutus menziesii Orange to red July-September berries Red Osier Dogwood Cornus sericea Plum-like fruits August- September Oregon White Oak Quercus garryana Acorns September- October Osoberry (Indian Plum) Oemleria cerasiformis Blue-black May-June small plums Hawthorn Crataegus sp. Black-purple July-August clusters of small “apples” (Lewis et al. 2003, Leigh, 1999)

LIMITING FACTORS Some limiting factors described by Lewis et. al for WDFW (2003) that can be remedied by landowners leading to the continued and sustained recovery of band-tailed pigeons include: Degradation of and lack of accessibility to mineral springs due to habitat destruction and invasion of non-native species Protection from forestland conversion and adverse habitat modification of suitable nesting habitat Loss of mast producing shrubs from forest succession, land development, and excessive use of herbicides in foraging areas Intensive hunting, especially at mineral spring locations Outbreaks of Trichomoniasis which is known to kill band-tailed pigeons. This parasite can be transmitted through contaminated feed at backyard bird feeders. Regular cleaning of feeders can help prevent outbreaks.

HABITAT RESTORATION AND ENHANCEMENT ACTIVITIES

Objective #1: Preserve habitat in and around known mineral spring sites. Method: 1. Preserve large trees used for perching around the springs. 2. Ensure spring accessibility to birds by removal of dense vegetation within and immediately around the seeps and springs. This may be necessary to provide unhampered access to the mineral-laden waters.

Objective #2: Encourage growth of mast producing trees and shrubs Method:

Existing Habitat Type Methods Practices Forest areas composed of a single tree Thin or remove clumps of the existing 490-Forest Site Preparation species (i.e. Douglas fir saplings, red species and interplant with species 612-Tree/Shrub Establishment alder, vine maple, etc.). listed in Table 1. Planting rate should 644-Wetland Wildlife Habitat be 250-300 mast producing species per Management acre. Underplanting may require 645-Upland Wildlife Habitat overstory thinning in some situations Management to assure adequate sunlight is available 660-Tree/Shrub Pruning for planted mast-producing shrubs. 666-Forest Stand Improvement Bareroot seedlings or direct seeding can be utilized.

Forest stands with mixed species 1. Underplant the stand with species 490-Forest Site Preparation overstory and limited understory from Table 1. Seeding rates should 612-Tree/Shrub Establishment diversity. be 250-300 stems per acre. This 660-Tree/Shrub Pruning may require overstory thinning in 644-Wetland Wildlife Habitat some situations to assure adequate Management sunlight is available for planted 645-Upland Wildlife Habitat mast-producing shrubs. Management 2. Create small clearings within the 666-Forest Stand Improvement forest landscape. Clearings can range from 0.25-1 acre in size. Seeding rate is 500 stems per acre. Landowners can also utilize existing clearings (roadsides, logging landing areas, etc.) for establishment of the mast producing plants.

Open farmland setting Plant hedgerows and field borders 382-Fence composed of species from Table 1. 386-Field Border Consider planting a diversity of plants 391-Riparian Forest Buffer that will continue to provide fruit 472-Use Exclusion throughout the breeding season (April- 490-Forest Site Preparation September). See Table 1 for fruiting 422-Hedgerow Planting season of the preferred plants. 612-Tree/Shrub Establishment Livestock should be excluded from 644-Wetland Wildlife Habitat these areas. Management 645-Upland Wildlife Habitat Management 666-Forest Stand Improvement

Objective #3: Incorporate mast producing trees and shrubs in o other conservation practices Method: When planning vegetative practices that will improve other resource concerns such as streambank erosion, wind erosion, and riparian buffer enhancement, include species from Table 1 in the planting plan. 1. Plants preferred by band-tailed pigeons can be incorporated into NRCS conservation practices listed in the FOTG. REFERENCES

Audubon, J. National Audubon Society field Guide to North American Birds, West Region. Miklos D.F. Udvardy. Revised by John Farrand, Jr. 1995. Alfred A. Knopf, New York. 822 pp.

Ehrlich, P. R., D.S. Dobkin, and D.W. Wheye. 1988. The Birder’s Handbook: A Field Guide to the Natural History of North American Birds. Simon & Schuster Inc., New York. 785 pps.

Jarvis, R.L., and M.F. Passmore. 1992. Ecology of band-tailed pigeons in Oregon. Biological Report, 6, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C.

Leigh, Michael. 1999. Grow Your Own Native Landscape: A Guide to Identifying, Propagating & Landscaping with Western Washington Native Plants. Washington State University Cooperative Extension. 116 pps.

Leonard, J.P. 1998. Nesting and foraging ecology of the band-tailed pigeon in western Oregon. Ph.D. Dissertation, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA.

Lewis, J.C, M. Tirhi, and D. Kraege. 2003. Band-tailed pigeon (Columba fasciata). In E.M. Larson, N. Nordstorm, and J. Azerrad, editors. Management Recommendations for Washington’s Priority Species, Volume IV: Birds [online]. Available http://www.wa.gov/wdfw/hab/phs/vol4/band pigeon.pdf.

Pacific Flyway Council. 1983. Pacific Coast band-tailed pigeon management plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, Oregon, USA.

Sanders, T.A. 2000. Habitat availability, dietary mineral supplement, and measuring abundance of band-tailed pigeons in western Oregon. Ph.D. Dissertation, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA.

Schroeder, M.A., and C.E. Braun. 1993.Movement and philopatry of band-tailed pigeons captured in Colorado. Journal of Wildlife Management 57:103-112. PERSONAL COMMUNICATIONS Jim Bottorff, Forest Stewardship Wildlife Biologist Habitat Management Division Washington Department of Natural Resources Olympia, Washington