Examining the Proper Role of Judicial Review in the Federal Regulatory Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sen. Ben Sasse (R-NE)

Sen. Ben Sasse (R-NE) Official Photo Navy League Advocates in State 27 Previous Contacts 6 Grassroots Actions Since July 2020 0 Address Room 107, Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510-2709 Next Election Term Before Politics 2026 2nd term Education, Public Official Education Education Yale University (CT) Ph.D. 2004 Yale University (CT) M.Phil Education Past Military Service Yale University (CT) M.A. None Bio Sen. Ben Sasse is a 2nd term Senator in the US Congress who represents Nebraska and received 67.4% of the vote in his last election. He is a member of the Judiciary, Budget, Intelligence, and Finance committees.He works most frequently on Health (14 bills), Crime and Law Enforcement (12 bills), Civil Rights and Liberties, Minority Issues (12 bills), Law (10 bills), and Civil actions and liability (8 bills). He has sponsored 37 bills in his last six year(s) in office, voting with his party 89.7% of the time, getting 5.41% of his bills out of committee, and 0.0% of his sponsored bills enacted.Sen. Sasse most frequently cosponsors Sea Service Installations in State: Co-Sponsored Bills We Support No bills for this official. Powered by Quorum Sen. Ben Sasse (R-NE) Committees Senate Committee on Finance Senate Committee on Budget Senate Committee on the Judiciary Senate Select Committee on Intelligence Subcommittees Senate Subcommittee on Federal Courts, Oversight,... Senate Subcommittee on Human Rights and the Law Senate Subcommittee on International Trade,... Senate Subcommittee on Privacy, Technology, and the... Senate Subcommittee on Social Security, Pensions,... Senate Subcommittee on Taxation and IRS Oversight Senate Subcommittee on the Constitution Committees Senate Committee on Finance Chairs: Sen. -

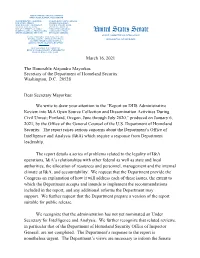

SSCI Senators to DHS Mayorkas Re

MARK R. WARNER, VIRGINIA, CHAIRMAN MARCO RUBIO, FLORIDA, VICE CHAIRMAN DIANNE FEINSTEIN, CALIFORNIA RICHARD BURR, NORTH CAROLINA RON WYDEN, OREGON JAMES E. RISCH, IDAHO MARTIN HEINRICH, NEW MEXICO SUSAN M. COLLINS, MAINE ANGUS S. KING, JR., MAINE ROY BLUNT, MISSOURI MICHAEL F. BENNET, COLORADO TOM COTTON, ARKANSAS ROBERT P. CASEY, JR., PENNSYLVANIA JOHN CORNYN, TEXAS United States Senate KIRSTEN GILLIBRAND, NEW YORK BEN SASSE, NEBRASKA SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE CHARLES SCHUMER, NEW YORK, EX OFFICIO MITCH MCCONNELL, KENTUCKY, EX OFFICIO WASHINGTON, DC 20510–6475 JACK REED, RHODE ISLAND, EX OFFICIO JAMES M. INHOFE, OKLAHOMA, EX OFFICIO MICHAEL CASEY, STAFF DIRECTOR BRIAN W. WALSH, MINORITY STAFF DIRECTOR KELSEY S. BAILEY, CHIEF CLERK March 16, 2021 The Honorable Alejandro Mayorkas Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security Washington, D.C. 20528 Dear Secretary Mayorkas: We write to draw your attention to the “Report on DHS Administrative Review into I&A Open Source Collection and Dissemination Activities During Civil Unrest; Portland, Oregon, June through July 2020,” produced on January 6, 2021, by the Office of the General Counsel of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. The report raises serious concerns about the Department’s Office of Intelligence and Analysis (I&A) which require a response from Department leadership. The report details a series of problems related to the legality of I&A operations, I&A’s relationships with other federal as well as state and local authorities, the allocation of resources and personnel, management and the internal climate at I&A, and accountability. We request that the Department provide the Congress an explanation of how it will address each of these issues, the extent to which the Department accepts and intends to implement the recommendations included in the report, and any additional reforms the Department may support. -

Key Committees 2021

Key Committees 2021 Senate Committee on Appropriations Visit: appropriations.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Patrick J. Leahy, VT, Chairman Richard C. Shelby, AL, Ranking Member* Patty Murray, WA* Mitch McConnell, KY Dianne Feinstein, CA Susan M. Collins, ME Richard J. Durbin, IL* Lisa Murkowski, AK Jack Reed, RI* Lindsey Graham, SC* Jon Tester, MT Roy Blunt, MO* Jeanne Shaheen, NH* Jerry Moran, KS* Jeff Merkley, OR* John Hoeven, ND Christopher Coons, DE John Boozman, AR Brian Schatz, HI* Shelley Moore Capito, WV* Tammy Baldwin, WI* John Kennedy, LA* Christopher Murphy, CT* Cindy Hyde-Smith, MS* Joe Manchin, WV* Mike Braun, IN Chris Van Hollen, MD Bill Hagerty, TN Martin Heinrich, NM Marco Rubio, FL* * Indicates member of Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee, which funds IMLS - Final committee membership rosters may still be being set “Key Committees 2021” - continued: Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Visit: help.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Patty Murray, WA, Chairman Richard Burr, NC, Ranking Member Bernie Sanders, VT Rand Paul, KY Robert P. Casey, Jr PA Susan Collins, ME Tammy Baldwin, WI Bill Cassidy, M.D. LA Christopher Murphy, CT Lisa Murkowski, AK Tim Kaine, VA Mike Braun, IN Margaret Wood Hassan, NH Roger Marshall, KS Tina Smith, MN Tim Scott, SC Jacky Rosen, NV Mitt Romney, UT Ben Ray Lujan, NM Tommy Tuberville, AL John Hickenlooper, CO Jerry Moran, KS “Key Committees 2021” - continued: Senate Committee on Finance Visit: finance.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Ron Wyden, OR, Chairman Mike Crapo, ID, Ranking Member Debbie Stabenow, MI Chuck Grassley, IA Maria Cantwell, WA John Cornyn, TX Robert Menendez, NJ John Thune, SD Thomas R. -

CALENDAR of BUSINESS Wednesday, January 6, 2021

SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES ONE HUNDRED SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS CONVENED JANUARY 3, 2021 FIRST SESSION ! " DAYS OF SESSION 2 SECOND SESSION ! " CALENDAR OF BUSINESS Wednesday, January 6, 2021 SENATE CONVENES AT 12:30 P.M. PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF JULIE E. ADAMS, SECRETARY OF THE SENATE By JOHN J. MERLINO, LEGISLATIVE CLERK www.SenateCalendar.gov 19–015 2 UNANIMOUS CONSENT AGREEMENTS 3 SSS2021 SSS JANUARY JULY Sun M Tu W Th F Sat Sun M Tu W Th F Sat 1 2 1 2 3 3 4 5 —–6 7 8 9 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 31 FEBRUARY AUGUST 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 28 29 30 31 MARCH SEPTEMBER 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 28 29 30 31 26 27 28 29 30 APRIL OCTOBER 1 2 3 1 2 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 25 26 27 28 29 30 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 MAY NOVEMBER 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 28 29 30 30 31 JUNE DECEMBER 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 27 28 29 30 26 27 28 29 30 31 JANUARY Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Days Senate met during First Session, One Hundred Seventeenth Congress, are marked (—–). -

Mcconnell Announces Senate Republican Committee Assignments for the 117Th Congress

For Immediate Release, Wednesday, February 3, 2021 Contacts: David Popp, Doug Andres Robert Steurer, Stephanie Penn McConnell Announces Senate Republican Committee Assignments for the 117th Congress Praises Senators Crapo and Tim Scott for their work on the Committee on Committees WASHINGTON, D.C. – Following the 50-50 power-sharing agreement finalized earlier today, Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) announced the Senate Republican Conference Committee Assignments for the 117th Congress. Leader McConnell once again selected Senator Mike Crapo (R-ID) to chair the Senate Republicans’ Committee on Committees, the panel responsible for committee assignments for the 117th Congress. This is the ninth consecutive Congress in which Senate leadership has asked Crapo to lead this important task among Senate Republicans. Senator Tim Scott (R-SC) assisted in the committee selection process as he did in the previous three Congresses. “I want to thank Mike and Tim for their work. They have both earned the trust of our colleagues in the Republican Conference by effectively leading these important negotiations in years past and this year was no different. Their trust and experience was especially important as we enter a power-sharing agreement with Democrats and prepare for equal representation on committees,” McConnell said. “I am very grateful for their work.” “I appreciate Leader McConnell’s continued trust in having me lead the important work of the Committee on Committees,” said Senator Crapo. “Americans elected an evenly-split Senate, and working together to achieve policy solutions will be critical in continuing to advance meaningful legislation impacting all Americans. Before the COVID-19 pandemic hit our nation, our economy was the strongest it has ever been. -

Using Activists' Pairwise Comparisons to Measure Ideology

Is John McCain more conservative than Rand Paul? Using activists' pairwise comparisons to measure ideology ∗ Daniel J. Hopkins Associate Professor University of Pennsylvania [email protected] Hans Noely Associate Professor Georgetown University [email protected] April 3, 2017 Abstract Political scientists use sophisticated measures to extract the ideology of members of Congress, notably the widely used nominate scores. These measures have known limitations, including possibly obscuring ideological positions that are not captured by roll call votes on the limited agenda presented to legislators. Meanwhile scholars often treat the ideology that is measured by these scores as known or at least knowable by voters and other political actors. It is possible that (a) nominate fails to capture something important in ideological variation or (b) that even if it does measure ideology, sophisticated voters only observe something else. We bring an alternative source of data to this subject, asking samples of highly involved activists to compare pairs of senators to one another or to compare a senator to themselves. From these pairwise comparisons, we can aggregate to a measure of ideology that is comparable to nominate. We can also evaluate the apparent ideological knowledge of our respondents. We find significant differences between nominate scores and the perceived ideology of politically sophisticated activists. ∗DRAFT: PLEASE CONSULT THE AUTHORS BEFORE CITING. Prepared for presentation at the annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association in Chicago, April 6-9, 2017. We would like to thank Michele Swers, Jonathan Ladd, and seminar participants at Texas A&M University and Georgetown University for useful comments on earlier versions of this project. -

Libertarian Party, Sample Ballot, Primary Election, May 12, 2020

Republican Party, Sample Ballot, Primary Election, May 12, 2020 Madison County, Nebraska State of Nebraska INSTRUCTIONS TO VOTERS PRESIDENTIAL TICKET CONGRESSIONAL TICKET 1. TO VOTE, YOU MUST DARKEN THE For President of the United States For Representative in Congress OVAL COMPLETELY ( ). Vote for ONE District 1 - Two Year Term 2. Use a black ink pen to mark the ballot. Vote for ONE 3. To vote for a WRITE-IN candidate, write Donald J. Trump in the name on the line provided AND Jeff Fortenberry darken the oval completely. Bill Weld 4. DO NOT CROSS OUT OR ERASE. COUNTY TICKET If you make a mistake, ask for a new UNITED STATES SENATORIAL TICKET For County Commissioner ballot. For United States Senator District 2 Six Year Term Vote for ONE Vote for ONE Eric Stinson Ben Sasse Chris Thompson Matt Innis Democratic Party, Sample Ballot, Primary Election, May 12, 2020 Madison County, Nebraska State of Nebraska PRESIDENTIAL TICKET UNITED STATES SENATORIAL TICKET CONGRESSIONAL TICKET For President of the United States For United States Senator For Representative in Congress Vote for ONE Six Year Term District 1 - Two Year Term Vote for ONE Vote for ONE Joe Biden Dennis Frank Maček Babs Ramsey Tulsi Gabbard Chris Janicek Kate Bolz Bernie Sanders Larry Marvin Elizabeth Warren Angie Philips Alisha Shelton Daniel M. Wik Andy Stock Libertarian Party, Sample Ballot, Primary Election, May 12, 2020 Madison County, Nebraska State of Nebraska PRESIDENTIAL TICKET UNITED STATES SENATORIAL TICKET CONGRESSIONAL TICKET For President of the United States For United States Senator For Representative in Congress Vote for ONE Six Year Term District 1 - Two Year Term Vote for ONE Vote for ONE Max Abramson Gene Siadek Dennis B. -

Congressional Record—Senate S3038

S3038 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE June 17, 2020 The clerk will call the roll. The bill clerk read as follows: EXECUTIVE SESSION The legislative clerk called the roll. CLOTURE MOTION Mr. DURBIN. I announce that the Senator from Massachusetts (Mr. MAR- We, the undersigned Senators, in accord- EXECUTIVE CALENDAR KEY) and the Senator from Washington ance with the provisions of rule XXII of the The PRESIDING OFFICER. Cloture (Mrs. MURRAY) are necessarily absent. Standing Rules of the Senate, do hereby having been invoked, the Senate will The PRESIDING OFFICER (Mr. move to bring to a close debate on the nomi- proceed to executive session to con- nation of Justin Reed Walker, of Kentucky, LANKFORD). Are there any other Sen- to be United States Circuit Judge for the sider the following nomination, which ators in the Chamber desiring to vote? District of Columbia Circuit. the clerk will report. The result was announced—yeas 73, Mitch McConnell, Tom Cotton, John The bill clerk read the nomination of nays 25, as follows: Boozman, Joni Ernst, Todd Young, Justin Reed Walker, of Kentucky, to be [Rollcall Vote No. 121 Leg.] Steve Daines, Cory Gardner, Jerry United States Circuit Judge for the YEAS—73 Moran, James E. Risch, Shelley Moore District of Columbia Circuit. Capito, David Perdue, Ben Sasse, Kevin Alexander Gillibrand Roberts The PRESIDING OFFICER (Mr. ROM- Cramer, Tim Scott, Lamar Alexander, Baldwin Graham Rosen NEY). The Senator from Vermont. Bennet Grassley Rubio Mike Rounds, Pat Roberts. Mr. LEAHY. Mr. President, this Blumenthal Harris Sanders The PRESIDING OFFICER. By unan- morning, the Senate narrowly invoked Blunt Hassan Schatz Booker Heinrich imous consent, the mandatory quorum cloture on the nomination of Justin Schumer Walker to the DC Circuit. -

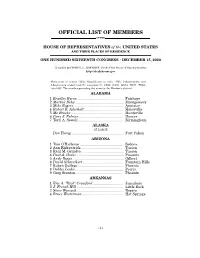

Official List of Members

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS • DECEMBER 15, 2020 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives http://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (233); Republicans in italic (195); Independents and Libertarians underlined (2); vacancies (5) CA08, CA50, GA14, NC11, TX04; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Bradley Byrne .............................................. Fairhope 2 Martha Roby ................................................ Montgomery 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................ -

114Th Congress 161

NEBRASKA 114th Congress 161 NEBRASKA (Population 2010, 1,826,341) SENATORS DEB FISCHER, Republican, of Valentine, NE; born in Lincoln, NE, March 1, 1951; edu- cation: B.S., University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, 1988; professional: rancher; Senator in the Nebraska Unicameral, 2005–13; President of the Nebraska Association of School Boards; Commissioner on the Coordinating Commission for Post-Secondary Education; Valentine Rural High School Board of Education; awards: BILLD Fellow, Midwest Council of State Govern- ments Bowhay Institute for Legislative Leadership, 2005; NRD Farm and Ranch Conservation Award, 1999; Nebraska Association of School Boards Lifetime Achievement Award, 1999; Ne- braska Rural Community Schools Association Outstanding Board Member Award, 1998–99; Nebraska Cattlemen Environmental Stewardship Award, 1995; Rangeman’s Award, Nebraska Section Society for Range Management, 1994; NRD State Grasslands Conservation Award, 1993; Kellogg Fellow, National Center for Food and Policy Research, Resources for the Future, Washington, DC, 1991; LEAD VIII Fellow, Nebraska Leadership Program, 1988–90; religion: Presbyterian; married: Bruce Fischer; three children, three grandchildren; caucuses: vice chair, Sportsmen’s Caucus; Senate Western Caucus; Senate Rural Health Caucus; General Aviation Caucus; Republican High-Tech Task Force; National Guard Caucus; committees: Armed Serv- ices; Commerce, Science, and Transportation; Environment and Public Works; Small Business and Entrepreneurship; elected to the U.S. Senate on November 6, 2012. Office Listings http://fischer.senate.gov 454 Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 .................................................. (202) 224–6551 Chief of Staff.—Joe Hack. FAX: 228–1325 Legislative Director.—Stephen Higgins. Communications Director.—Thomas Doheny. Administrative Director.—Sherri Hupart. 11819 Miracle Hills Drive, Suite 205, Omaha, NE 68154 ...................................................... -

GUIDE to the 117Th CONGRESS

GUIDE TO THE 117th CONGRESS Table of Contents Health Professionals Serving in the 117th Congress ................................................................ 2 Congressional Schedule ......................................................................................................... 3 Office of Personnel Management (OPM) 2021 Federal Holidays ............................................. 4 Senate Balance of Power ....................................................................................................... 5 Senate Leadership ................................................................................................................. 6 Senate Committee Leadership ............................................................................................... 7 Senate Health-Related Committee Rosters ............................................................................. 8 House Balance of Power ...................................................................................................... 11 House Committee Leadership .............................................................................................. 12 House Leadership ................................................................................................................ 13 House Health-Related Committee Rosters ............................................................................ 14 Caucus Leadership and Membership .................................................................................... 18 New Members of the 117th -

116Th Congress 163

NEBRASKA 116th Congress 163 NEBRASKA (Population 2010, 1,826,341) SENATORS DEB FISCHER, Republican, of Valentine, NE; born in Lincoln, NE, March 1, 1951; edu- cation: B.S., University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, 1988; professional: rancher; Senator in the Nebraska Unicameral, 2005–13; president of the Nebraska Association of School Boards; commissioner on the Coordinating Commission for Post-Secondary Education; Valentine Rural High School Board of Education; awards: BILLD Fellow, Midwest Council of State Govern- ments Bowhay Institute for Legislative Leadership, 2005; NRD Farm and Ranch Conservation Award, 1999; Nebraska Association of School Boards Lifetime Achievement Award, 1999; Ne- braska Rural Community Schools Association Outstanding Board Member Award, 1998–99; Nebraska Cattlemen Environmental Stewardship Award, 1995; Rangeman’s Award, Nebraska Section Society for Range Management, 1994; NRD State Grasslands Conservation Award, 1993; Kellogg Fellow, National Center for Food and Policy Research, Resources for the Future, Washington, DC, 1991; LEAD VIII Fellow, Nebraska Leadership Program, 1988–90; religion: Presbyterian; married: Bruce Fischer; three children; three grandchildren; caucuses: co-chair, Sportsmen’s Caucus; National Guard Caucus; Pro-Life Caucus; Senate Western Caucus; com- mittees: Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry; Armed Services; Commerce, Science, and Trans- portation; Rules and Administration; elected to the U.S. Senate on November 6, 2012; reelected to the U.S. Senate on November 6, 2018. Office Listings https://fischer.senate.gov https://facebook.com/senatordebfischer https://twitter.com/SenatorFischer 454 Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 ................................................. (202) 224–6551 Chief of Staff.—Joe Hack. FAX: 228–1325 Legislative Director.—Emily Leviner. Communications Director.—Brianna Puccini. Administrative Director.—Sherri Hupart.