A Tale of Two Small-Cap Benchmarks: 10 Years Later

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monthly Economic Update

In this month’s recap: Stocks moved higher as investors looked past accelerating inflation and the Fed’s pivot on monetary policy. Monthly Economic Update Presented by Ray Lazcano, July 2021 U.S. Markets Stocks moved higher last month as investors looked past accelerating inflation and the Fed’s pivot on monetary policy. The Dow Jones Industrial Average slipped 0.07 percent, but the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index rose 2.22 percent. The Nasdaq Composite led, gaining 5.49 percent.1 Inflation Report The May Consumer Price Index came in above expectations. Prices increased by 5 percent for the year-over-year period—the fastest rate in nearly 13 years. Despite the surprise, markets rallied on the news, sending the S&P 500 to a new record close and the technology-heavy Nasdaq Composite higher.2 Fed Pivot The Fed indicated that two interest rate hikes in 2023 were likely, despite signals as recently as March 2021 that rates would remain unchanged until 2024. The Fed also raised its inflation expectations to 3.4 percent, up from its March projection of 2.4 percent. This news unsettled 3 the markets, but the shock was short-lived. News-Driven Rally In the final full week of trading, stocks rallied on the news of an agreement regarding the $1 trillion infrastructure bill and reports that banks had passed the latest Federal Reserve stress tests. Sector Scorecard 07072021-WR-3766 Industry sector performance was mixed. Gains were realized in Communication Services (+2.96 percent), Consumer Discretionary (+3.22 percent), Energy (+1.92 percent), Health Care (+1.97 percent), Real Estate (+3.28 percent), and Technology (+6.81 percent). -

Russell 2000® Index Measures the Performance of the Small-Cap US Equity Market Segment of the US Equity Universe

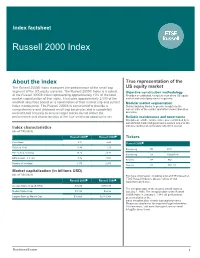

Index factsheet Russell 2000 Index About the index True representation of the The Russell 2000® Index measures the performance of the small-cap US equity market segment of the US equity universe. The Russell 2000® Index is a subset Objective construction methodology of the Russell 3000® Index representing approximately 10% of the total Provides an unbiased, complete view of the US equity market capitalization of that index. It includes approximately 2,000 of the market and underlying market segments smallest securities based on a combination of their market cap and current Modular market segmentation index membership. The Russell 2000® is constructed to provide a Distinct building blocks to provide insight into the comprehensive and unbiased small-cap barometer and is completely current state of the market and inform asset allocation reconstituted annually to ensure larger stocks do not distort the decisions performance and characteristics of the true small-cap opportunity set. Reliable maintenance and governance Disciplined, reliable maintenance process backed by a well-defined, balanced governance system ensures the Index characteristics indexes continue to accurately reflect the market (As of 7/31/2021) Russell 2000® Russell 3000® Tickers Price/Book 2.71 4.46 Russell 2000® Dividend Yield 0.99 1.26 Bloomberg PR RTY P/E Ex-Neg Earnings 19.25 24.71 Bloomberg TR RU20INTR EPS Growth - 5 Years 9.76 17.01 Reuters PR .RUT Number of Holdings 1,975 2,997 Reuters TR .RUTTU Market capitalization (in billions USD) (As of 7/31/2021) For more information, including a list of ETFs based on FTSE Russell Indexes, please call us or visit Russell 2000® Russell 3000® www.ftserussell.com Average Market Cap ($-WTD) $3.274 $478.338 The inception date of the Russell 2000® Index is Median Market Cap $1.193 $2.636 January 1, 1984. -

Small Cap Is Active Management's Rightful Home

SMALL CAP IS ACTIVE MANAGEMENT’S RIGHTFUL HOME Recent trends show a growing willingness among investors to apply indexing’s logic farther down the market-cap ladder. But, when it comes to smaller companies, the indexing argument isn’t very convincing. Maintaining exposure to the small-cap “category” through an index-based product eliminates the chance to benefit in an area that, we contend, offers active managers with fundamentals-based strategies the most consistent and pronounced opportunity to generate excess return. PASSIVE INFLUX: FUNDS FORM THE FOUNDATION WHILE ETFS KEEP PILING ON… The Vanguard Group introduced the first index fund at the end of 1975 as a low-cost way for investors to gain exposure to the companies of the S&P 500 Index, which account for roughly 80 percent of the stock market’s total capitalization. The strategy initially attracted $11 million in assets under management. According to S&P Dow Jones Indices, more than $7.8 trillion is currently benchmarked to the S&P 500 Index, “with index assets comprising approximately $2.2 trillion of this total.” Other estimates put indexing’s reach at more than one out of every three shares outstanding among the index’s component companies. The emergence of exchange-traded funds (ETFs), the first of which was launched in 1993 to track the S&P 500 Index, only adds momentum to passive investing’s growing presence within the equity market. Since 2008, when the SEC broadened the scope of allowable ETF strategies, the number of ETFs more than doubled to 1,594 through the end of 2015. -

Calamos Small Cap Market Snapshot

DATA AS OF 6/30/2021 WHAT’S NEW MARKET PULSE A little early…Last month, I made the bold prediction that the small cap MONTH-TO-DATE RETURNS correction was over. However, in June, they lagged by another 57 basis points R 2000 VALUE RUSSELL 2000 R 2000 GROWTH (Russell 2000 less Russell 1000). Falling 10-year Treasury yields during the last few weeks spooked many investors into rotating away from small caps. -0.61 1.94 4.69 R MICROCAP VALUE RUSSELL MICROCAP R MICROCAP GROWTH Even so, I’m not wavering. Small cap fundamentals continue to be rock-solid -0.63 2.19 6.36 and valuations versus large caps continue to look inexpensive, sitting at the 22nd percentile. In each of the past three small cap cycle peaks, valuations versus YEAR-TO-DATE RETURNS large caps surpassed the 83rd percentile. Small caps have a long way to go. I R 2000 VALUE RUSSELL 2000 R 2000 GROWTH conclude with an amazing small cap fact: since 1989, when small caps were up 26.69 17.54 8.98 more than 10% during the first six months of the year (the Russell 2000 was up R MICROCAP VALUE RUSSELL MICROCAP R MICROCAP GROWTH 17.5% in 1H 21), they continued to rise in the second half of the year, on average by another 12%. Buy the dip! 35.65 29.02 20.57 Brandon M. Nelson, CFA, Calamos Senior Portfolio Manager RUSSELL 2000 GROWTH VS. RUSSELL 1000 GROWTH RUSSELL 2000 GROWTH VS. S&P 500 GROWTH 300-DAY PERFORMANCE GICS SECTOR ALLOCATIONS (NET) 60% 50% Russell 2000 Growth 50% 40% S&P 500 Growth 40% 30% 30% 20% 20% 10% 10% 0% 0% -10% -20% -30% -40% 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 Past performance is not indicative of future results. -

Investing in the Marketplace

Investing in the Marketplace Prudential Retirement When you hear people talk about “the market,” you might think Did you know... we agree on what that means. Truth is, there are many indexes that represent differing segments of the market. And these …there is even indexes don’t always move in tandem. Understanding some of an index that the key ones can help you diversify your investments to better represent the economy as a whole. purports to track The Dow Jones Industrial Average (The Dow) is one of the oldest, most investor anxiety? well-know indexes and is often used to represent the economy as a Dubbed “The Fear whole. Truth is, though, The Dow only includes 30 stocks of the world’s largest, most influential companies. Why is it called an “average?” Index,” the proper Originally, it was computed by adding up the per-share price of its stocks, and dividing by the number of companies. name of the Chicago The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index (made up of 500 of the most widely- Board Options traded U.S. stocks) is larger and more diverse than The Dow. Because it represents about 70% of the total value of the U.S. stock market, the Exchange’s index is S&P 500 is a better indication of how the U.S. marketplace is moving as a whole. the VIX Index, Sometimes referred to as the “total stock market index,” the Wilshire and measures the 5000 Index includes about 7,000 of the more than 10,000 publicly traded companies with headquarters in the U.S. -

Risk-Adjusted Return Monitor Summary & Views

a global macro investment newsletter by Neil Azous Morning Edition | October 12, 2018 Risk-Adjusted Return Monitor CROSS-ASSET FOREX FIXED INCOME EQUITIES COMMODITIES THEMATIC PAIRS India SENSEX EUR/CNY UK 5-Yr Gilt India SENSEX Soybean China Exposure EU Cyclicals vs Defensives Saudi Tadawul USD/TWD South Korea 10-Yr Saudi Tadawul Gold None EU Domestic vs EM Exposure * Highlights the largest overnight positive and negative risk-adjusted returns across 160+ market proxies Summary & Views Contents These Are Not The Droids You Are Looking For Summary & Views Top Observations . The Pedestrian View Tracking Portfolio . Our View – Mutual Funds Economic Data . Our View – Hedge Funds . Our View – Global Macro . Financial Conditions Tracking Portfolio Admin – Schedule Tracking Portfolio Twitter @sbstimestamp The next edition of Sight Beyond Sight will be delivered on Monday. Bloomberg MCRO <go> Any updates to the tracking portfolio will be sent via Twitter (@sbstimestamp) or Bloomberg (MCRO<go>). Links Subscribe Now! Newsroom View Archive Permissions/Reprints Connect Twitter @neilazous These Are Not The Droids You Are Looking For The Pedestrian View This is the 23rd correction greater than 5% in the S&P 500 Index (SPX) since the March 2009 low. The average correction is -9.3% and the median correction is -8.4%. The average VIX peak is 32.1 and median peak is 30.3. From the high-to-low, the S&P 500 fell 7.8%, and the VIX peaked at 28.84. Add in the drawdowns in other benchmarks – Russell 2000 Index (RTY) -11.29% and NASDAQ-100 Index (NDX) - 10.49% – and the dozens of intra-day indicators showing extremes, and it is easier to understand that the correction is largely complete. -

Mr. Alp Eroglu International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) Calle Oquendo 12 28006 Madrid Spain

1301 Second Avenue tel 206-505-7877 www.russell.com Seattle, WA 98101 fax 206-505-3495 toll-free 800-426-7969 Mr. Alp Eroglu International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) Calle Oquendo 12 28006 Madrid Spain RE: IOSCO FINANCIAL BENCHMARKS CONSULTATION REPORT Dear Mr. Eroglu: Frank Russell Company (d/b/a “Russell Investments” or “Russell”) fully supports IOSCO’s principles and goals outlined in the Financial Benchmarks Consultation Report (the “Report”), although Russell respectfully suggests several alternative approaches in its response below that Russell believes will better achieve those goals, strengthen markets and protect investors without unduly burdening index providers. Russell is continuously raising the industry standard for index construction and methodology. The Report’s goals accord with Russell’s bedrock principles: • Index providers’ design standards must be objective and sound; • Indices must provide a faithful and unbiased barometer of the market they represent; • Index methodologies should be transparent and readily available free of charge; • Index providers’ operations should be governed by an appropriate governance structure; and • Index providers’ internal controls should promote efficient and sound index operations. These are all principles deeply ingrained in Russell’s heritage, practiced daily and they guide Russell as the premier provider of indices and multi-asset solutions. Russell is a leader in constructing and maintaining securities indices and is the publisher of the Russell Indexes. Russell operates through subsidiaries worldwide and is a subsidiary of The Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company. The Russell Indexes are constructed to provide a comprehensive and unbiased barometer of the market segment they represent. All of the Russell Indexes are reconstituted periodically, but not less frequently than annually or more frequently than monthly, to ensure new and growing equities and fixed income securities are reflected in its indices. -

What Every Investor Needs to Know About Investing Internationally

STRATEGIC GLOBAL ADVISORS, LLC What Every Investor Needs to Know About Investing Internationally In this report, you will discover what every investor needs to know about international investing and the common myths that keep investors from investing abroad. Investors who are serious about diversification will diversify not only across stocks and industries but also across countries. Investors may find more, and often better, investment opportunities when they broaden their investments worldwide rather than when they limit themselves to only one country. Are You Ignoring Over Half of the World’s Investment Opportunities? The United States’ share of the global marketplace, in terms of total market capitalization, is 42%. If U.S. investors wanted to benchmark the globe, their portfolios would have approximately a 58% exposure to foreign markets. The U.S. market share is shrinking as China, India and other emerging markets continue to grow. Share of Global Marketplace 7 YEARS AGO TODAY THE AMERICAS THE AMERICAS UK EX-US UK EX-US 14% 3% 9% 7% ASIA PACIFIC JAPAN ASIA PACIFIC EX-JAPAN 8% EX-JAPAN JAPAN 4% 11% 10% EUROPE EX-UK EUROPE EX-UK 18% 18% AFRICA/ASIA/M.E. US 1% 52% AFRICA/ASIA/M.E. US 3% 42% As of June 30, 2002. As of June 30, 2009. Source: MSCI ACWI Index, see disclosures for Index definition. Source: MSCI ACWI Index, see disclosures for Index definition. Do You Suffer From “Home Bias”?1 If you answer yes to any of the following questions, you may have a case of investor “home bias.” • Do you prefer to hold stocks that are located geographically close to you? • Do you prefer to invest in companies that use your native tongue in company reports and whose CEO shares your cultural background? • Do you tend to buy telecom stocks that are located in your state, rather than a different state? The tendency to invest locally occurs when investors know more about local industries and companies. -

Daily-Market-Update Page 1 Date 16-Nov-2020

Daily-Market-Update Page 1 Date 16-Nov-2020 Overnight/Asia NEWS Asian stocks and U.S. futures climbed on Monday, buoyed by positive sentiment on regional trade and signs of opposition to a national American lockdown despite surging virus cases. The dollar retreated. The Asian benchmark was on track for a record close, with Japan and South Korea outperforming. A slew of Asia-Pacific nations on Sunday signed the world’s largest regional free-trade agreement, encompassing nearly a third of the world’s population and gross domestic product. In Australia, share trading was paused due to a market data issue. S&P 500 futures extended last week’s advance after advisers to President-elect Joe Biden said they opposed a nationwide U.S. lockdown. Oil pushed higher and Treasuries were steady. On Friday, both the S&P 500 and the Russell 2000 Index of small caps rallied to all-time highs. The tech-heavy Nasdaq 100 underperformed amid the rotation to economically sensitive industries. Global stocks have recovered to pre-pandemic highs after optimism about a vaccine last week drove a rotation into value and cyclical sectors, and more defensive industries underperformed. Still, concerns about a sustainable economic recovery persist amid a flare-up in cases around the world. China remains a bright spot. Data showed the country’s economic recovery strengthened in October, with consumer spending picking up steadily and industrial production and investment rising faster than expected. The nation’s central bank added funds to the financial system to support growth. The pandemic continues to escalate in regions such as Europe and the U.S. -

ETF/ETN Monthly Report Jan-2015

issue month ETF/ETN Monthly Report Jan-2015 ◆Market Summary ETF/ETN trading in December remained strong, with one new ETF listing. ■ In December 2014, trading in the ETF/ETN market continued near record highs, with monthly trading value of approximately JPY 3.9 trillion and daily average trading value of about JPY 188 billion. ■ Activity in the Simplex WTI ETF (1671) grew sharply, as it rose to 18th in trading value. Other ETFs and ETNs tracking oil sector indices also saw significant gains. ■ NEXT NOTES S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats Net Total Return Index ETN (2044), listed in November 2014, was ranked 20th overall again. ◆Trading Value - Monthly(Auction) (Dec-2014) Total(JPY) Daily Average (JPY) ◆Trading days:21 Month on Month 3,940,493,727,840 187,642,558,469 -15.34% ◆Rankings ETF 163 ● Monthly trading value (Dec-2014) ETN 27 Monthly Trading Value, Fund # Code Name Underlying index/commodity Category Monthly Change (%) Value (unit: JPY 1,000) Administrator 1 1570 NEXT FUNDS Nikkei 225 Leveraged Index Exchange Traded Fund Nikkei 225 Leveraged Index Domestic Stock Indices 2,590,240,484 -13.11% Nomura AM 2 1321 Nikkei 225 Exchange Traded Fund Nikkei 225 Domestic Stock Indices 253,902,243 -30.77% Nomura AM 3 1579 Nikkei 225 Bull 2x ETF Nikkei 225 Leveraged Index Leveraged / Inverse Index 171,281,433 -11.30% Simplex AM 4 1357 NEXT FUNDS Nikkei 225 Double Inverse Index Exchange Traded Fund Nikkei 225 Double Inverse Index Leveraged / Inverse Index 163,756,627 -11.59% Nomura AM 5 1568 TOPIX Bull 2x ETF TOPIX Leveraged (2x) Index Leveraged / -

Quarterly Economic Update Andrew Van Erp Preferred Planning Associates

QUARTERLY ECONOMIC UPDATE ANDREW VAN ERP PREFERRED PLANNING ASSOCIATES In this Q4 recap: waves of volatility hit Wall Street, trade pacts and disputes make headlines, oil takes a plunge, and the economy continues to perform well. Andrew Van Erp Quarterly Economic Update 513.529.6094 (Office) 513.678.6406 (Mobile) [email protected] A review of Q4 2018, Presented by Andrew Van Erp THE QUARTER IN BRIEF Wall Street saw many ups and downs in the last three months of 2018. The fourth quarter concluded with bulls and bears vying for control of the market and with the S&P 500 suffering a 13.97%, three-month loss. The Federal Reserve sent conflicting signals about its implementation of monetary policy normalization, to the frustration of investors. No real progress was made in resolving the U.S.-China trade war, and the Brexit appeared to reach a standstill. The price of oil dropped sharply. The housing market gained a bit of momentum as home prices and mortgage rates both declined. The quarter was quite newsworthy, but its major headlines raised some troubling questions about the direction of the markets. 1 Annual DOMESTIC ECONOMIC HEALTH Bill Consolidation On the whole, the economy looked quite good in the fall. Consumer spending increased Loan Special! 0.8% for October and 0.4% for November, with retail sales up 1.1% in the tenth month of the year and 0.2% in the eleventh. Retailers benefited from a great holiday sales season: Lower Your on an annualized basis, consumer purchases made between November 1 and December Monthly 24 were up 5.1% compared to the same period in 2017. -

Calamos Small Cap Market Snapshot

DATA AS OF 4/30/2021 WHAT’S NEW MARKET PULSE Two-month pullback…During April, small caps struggled for the second month in MONTH-TO-DATE RETURNS a row, trailing large caps by 328 basis points (Russell 2000 less Russell 1000). R 2000 VALUE RUSSELL 2000 R 2000 GROWTH Most of the small cap damage was done in the first half of the month—things 2.02 2.10 2.18 stabilized in the second half. R MICROCAP VALUE RUSSELL MICROCAP R MICROCAP GROWTH Despite the recent sluggishness, we continue to think we are in the early stages 1.10 0.26 -0.89 of a multiyear run of outperformance for small caps. From a macro perspective, YEAR-TO-DATE RETURNS small caps tend to perform well during periods like now with rising economic growth and rising inflation. From a micro perspective, fundamentals remain R 2000 VALUE RUSSELL 2000 R 2000 GROWTH extremely strong and long-term forward valuations vs. large caps have now 23.62 15.07 7.16 pulled back to the 30th percentile, a likely attractive entry point. Additionally, R MICROCAP VALUE RUSSELL MICROCAP R MICROCAP GROWTH given the rising likelihood for higher capital gains taxes, we expect to hear about 30.86 24.21 15.82 more merger and acquisition (M&A) activity, which could disproportionately benefit small cap companies looking to sell out prior to the potential tax hike. Brandon M. Nelson, CFA, Calamos Senior Portfolio Manager RUSSELL 2000 GROWTH VS. RUSSELL 1000 GROWTH RUSSELL 2000 GROWTH VS. S&P 500 GROWTH 300-DAY PERFORMANCE GICS SECTOR ALLOCATIONS (NET) 60% 50% 50% Russell 2000 Growth 40% 40% S&P 500 Growth 30% 30% 20% 20% 10% 0% 10% -10% 0% -20% -30% -40% 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 Past performance is not indicative of future results.