Outside Reading: Pop Culture

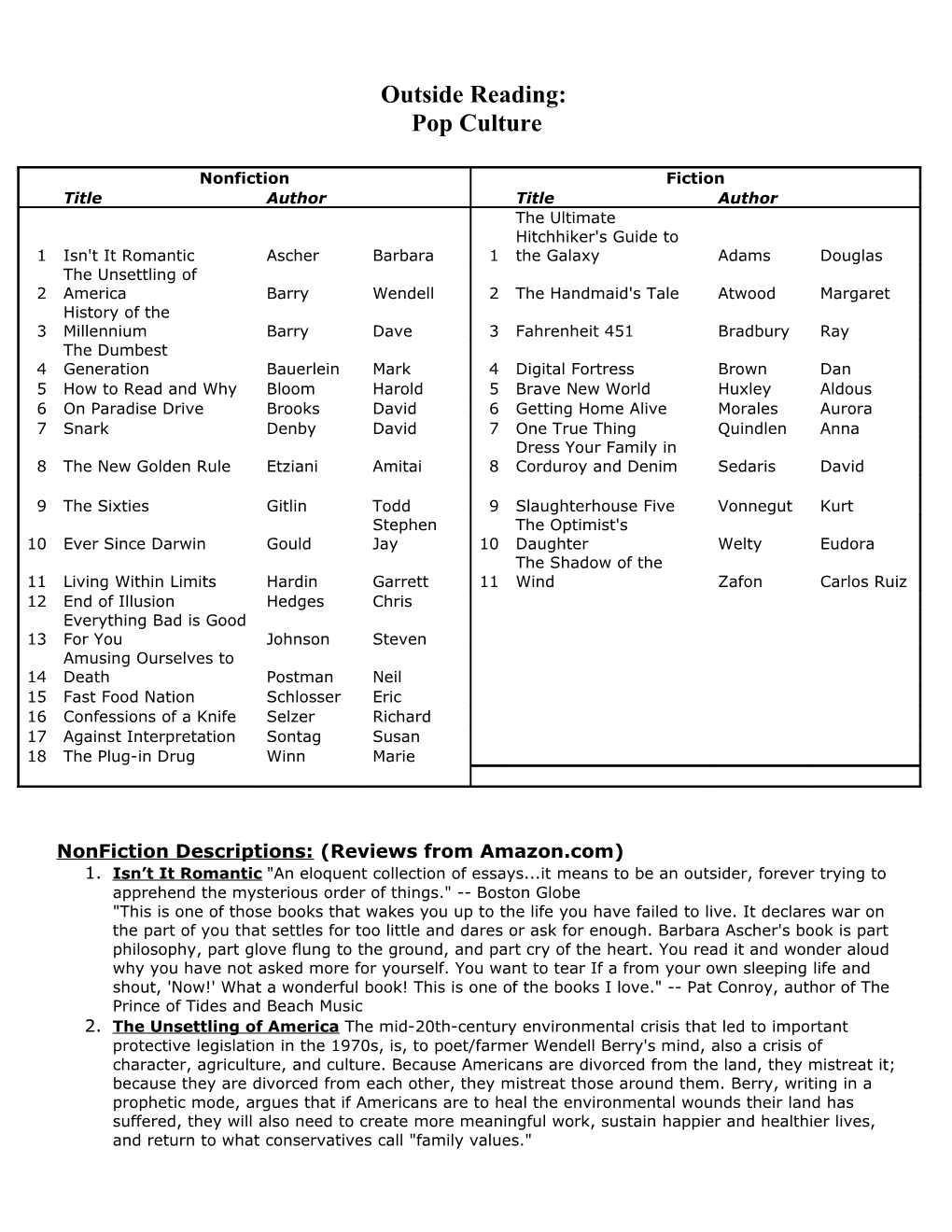

Nonfiction Fiction Title Author Title Author The Ultimate Hitchhiker's Guide to 1 Isn't It Romantic Ascher Barbara 1 the Galaxy Adams Douglas The Unsettling of 2 America Barry Wendell 2 The Handmaid's Tale Atwood Margaret History of the 3 Millennium Barry Dave 3 Fahrenheit 451 Bradbury Ray The Dumbest 4 Generation Bauerlein Mark 4 Digital Fortress Brown Dan 5 How to Read and Why Bloom Harold 5 Brave New World Huxley Aldous 6 On Paradise Drive Brooks David 6 Getting Home Alive Morales Aurora 7 Snark Denby David 7 One True Thing Quindlen Anna Dress Your Family in 8 The New Golden Rule Etziani Amitai 8 Corduroy and Denim Sedaris David

9 The Sixties Gitlin Todd 9 Slaughterhouse Five Vonnegut Kurt Stephen The Optimist's 10 Ever Since Darwin Gould Jay 10 Daughter Welty Eudora The Shadow of the 11 Living Within Limits Hardin Garrett 11 Wind Zafon Carlos Ruiz 12 End of Illusion Hedges Chris Everything Bad is Good 13 For You Johnson Steven Amusing Ourselves to 14 Death Postman Neil 15 Fast Food Nation Schlosser Eric 16 Confessions of a Knife Selzer Richard 17 Against Interpretation Sontag Susan 18 The Plug-in Drug Winn Marie

NonFiction Descriptions: (Reviews from Amazon.com) 1. Isn’t It Romantic "An eloquent collection of essays...it means to be an outsider, forever trying to apprehend the mysterious order of things." -- Boston Globe "This is one of those books that wakes you up to the life you have failed to live. It declares war on the part of you that settles for too little and dares or ask for enough. Barbara Ascher's book is part philosophy, part glove flung to the ground, and part cry of the heart. You read it and wonder aloud why you have not asked more for yourself. You want to tear If a from your own sleeping life and shout, 'Now!' What a wonderful book! This is one of the books I love." -- Pat Conroy, author of The Prince of Tides and Beach Music 2. The Unsettling of America The mid-20th-century environmental crisis that led to important protective legislation in the 1970s, is, to poet/farmer Wendell Berry's mind, also a crisis of character, agriculture, and culture. Because Americans are divorced from the land, they mistreat it; because they are divorced from each other, they mistreat those around them. Berry, writing in a prophetic mode, argues that if Americans are to heal the environmental wounds their land has suffered, they will also need to create more meaningful work, sustain happier and healthier lives, and return to what conservatives call "family values." 3. History of the Millennium Humorist Barry offers a look at the new millennium thus far in this collection of the annual reviews that Barry offers through his newspaper columns. It consists of month-to-month commentary on the most outrageous events of the year—Janet Jackson's wardrobe malfunction, the "heck of a job" done by Michael Brown during Hurricane Katrina, the failure to find WMDs in Iraq—all delivered with Barry's hilarious look at the absurdities of American life. The book includes 32 line drawings that add to the fun, as well as a bonus look at history during the first millennium, from 1000 through 1999. Barry fans and readers looking for a lighter perspective on the history of world events will enjoy this book. Bush, Vanessa 4. The Dumbest Generation It’s an irony so commonplace it’s become almost trite: despite the information superhighway, despite a world of knowledge at their fingertips, the younger generation today is less informed, less literate, and more self-absorbed than any that has preceded it. But why? According to the author, an English professor at Emory University, there are plenty of reasons. The immediacy and intimacy of social-networking sites have focused young people’s Internet use on themselves and their friends. The material they’re studying in school (such as the Civil War or The Great Gatsby) seems boring because it isn’t happening right this second and isn’t about them. They’re using the Internet not as a learning tool but as a communications tool: instant messaging, e-mail, chat, blogs. And the language of Internet communication, with its peculiar spelling, grammar, and punctuation, actually encourages illiteracy by making it socially acceptable. It wouldn’t be going too far to call this book the Why Johnny Can’t Read for the digital age. Some will disagree vehemently; others will nod sagely, muttering that they knew it all along. 5. How to Read and Why Bloom is never heavy, since his vision quest contains a healthy love of irony--Jedediah Purdy, take note: "Strip irony away from reading, and it loses at once all discipline and all surprise." And this supreme critic makes us want to equal his reading prowess because he writes as well as he reads; his epigrams are equal to his opinions. He is also a master allusionist and quoter. His section on Hedda Gabler is preceded by three extraordinary statements, two from Ibsen, who insists, "There must be a troll in what I write." Who would not want to proceed? Of course, Bloom can also accomplish his goal by sheer obstinacy. As far as he is concerned, Don Quixote may have been the first novel but it remains to this day the best one. Is he perhaps tweaking us into reading this gigantic masterwork by such bald overstatement? Bloom knows full well that a prophet should stop at nothing to get his belief and love across, and throughout How to Read and Why he is as unstinting as the visionary company he adores. 6. On Paradise Drive For readers who are feeling glum about America and its place in the world, or those who despairingly look at our culture's cookie cutter, strip mall consumerism and flash-bang glitter, Brooks (Bobos in Paradise) offers a balm with his latest pseudo-sociological treatise. More a way to look at what he sees as America's problems (e.g., our thirst for enormous gas guzzlers and super-sized soft drinks) with optimism than a series of suggestions of how to fix them, this book by the New York Times op-ed columnist tells readers it's okay to consume, consume, consume-so long as they look toward the future while doing so. At times playful and sarcastic (though less funny than intended), the book jumps from statistical analysis to cultural observation to defense of Bush's foreign policy, all without much of a mooring in essential context or factual citation. This is deceptive optimism; one long essay insisting our society's problems are not so big, provided we talk about them in the right way. 7. Snark In this highly entertaining essay, Denby traces the history of snark through the ages, starting with its invention as personal insult in the drinking clubs of ancient Athens, tracking its development all the way to the age of the Internet, where it has become the sole purpose and style of many media, political, and celebrity Web sites. Snark releases the anguish of the dispossessed, envious, and frightened; it flows when a dying class of the powerful struggles to keep the barbarians outside the gates, or, alternately, when those outsiders want to take over the halls of the powerful and expel the office-holders. Snark was behind the London-based magazine Private Eye, launched amid the dying embers of the British empire in 1961; it was also central to the career-hungry, New York-based magazine Spy. It has flourished over the years in the works of everyone from the startling Roman poet Juvenal to Alexander Pope to Tom Wolfe to a million commenters snarling at other people behind handles. Thanks to the grand dame of snark, it has a prominent place twice a week on the opinion page of the New York Times. 8. The New Golden Rule A leading communitarian thinker, sociologist Etzioni contends Americans have overemphasized individual rights in recent years. In his searching treatise, he seeks to restore an equilibrium between personal liberty and the common good, urging the diverse strands of America's social fabric to come together, to commit to a core of shared values that will help renew the family, schools and public institutions. Arguing that rights and responsibilities go hand in hand, he champions the two-parent family, national service involving voluntary participation in agencies such as the Peace Corps and Vista, a nationally standardized public school curriculum, community courts as alternatives to the official judicial system, schools as character-building agents and devolving federal functions to voluntary associations and other community bodies. Challenging liberals and conservatives alike, Etzioni, a professor at George Washington University, cuts through a welter of issues, from bicultural education to curbing alcohol abuse, in this timely contribution to the debate over what constitutes a good society. 9. The Sixties The author was elected president of Students for a Democratic Society in 1963, and he brings an insider's perspective to bear on the turbulent whirl of political, social, and sexual rebellion we now call "the sixties." Gitlin does a nice job of integrating his first-person recollections with a broader history that ranges from the roots of 1960s revolt in 1950s affluence and complacency to the movement's apocalyptic collapse in the early 1970s--a victim of its own excesses as well as governmental persecution. His lucid summary of the complex strands that intertwined to form the counterculture is essential basic reading for those who don't know the difference between the Diggers and the Yippies. 10. Ever Since Darwin This popular anthology offers an introduction to the wonders and depths of evolutionary biology. "A remarkable achievement by any measure . . . One is hard pressed to single out past writers who could wear the sobriquet of natural history essayist with such distinction."--Chicago Tribune. 11. Living Within Limits "We fail to mandate economic sanity," writes Garrett Hardin, "because our brains are addled by...compassion." With such startling assertions, Hardin has cut a swathe through the field of ecology for decades, winning a reputation as a fearless and original thinker. A prominent biologist, ecological philosopher, and keen student of human population control, Hardin now offers the finest summation of his work to date, with an eloquent argument for accepting the limits of the earth's resources--and the hard choices we must make to live within them. 12. Empire of Illusion Pulitzer prize–winner Chris Hedges charts the dramatic and disturbing rise of a post-literate society that craves fantasy, ecstasy and illusion. Chris Hedges argues that we now live in two societies: One, the minority, functions in a print- based, literate world, that can cope with complexity and can separate illusion from truth. The other, a growing majority, is retreating from a reality-based world into one of false certainty and magic. In this “other society,” serious film and theatre, as well as newspapers and books, are being pushed to the margins. 13. Everything Bad is Good For You Worried about how much time your children spend playing video games? Don't be, advises Johnson—not only are they learning valuable problem- solving skills, they'd probably do better on an IQ test than you or your parents could at their age. Go ahead and let them watch more television, too, since even reality shows can function as "elaborately staged group psychology experiments" to stimulate rather than pacify the brain. With the same winning combination of personal revelation and friendly scientific explanation he displayed in last year's Mind Wide Open, Johnson shatters the conventional wisdom about pop culture as pabulum, showing how video games, television shows and movies have become increasingly complex. Furthermore, he says, consumers are drawn specifically to those products that require the most mental engagement, from small children who can't get enough of their favorite Disney DVDs to adults who find new layers of meaning with each repeated viewing of Seinfeld. Johnson lays out a strong case that what we do for fun is just as educational in its way as what we study in the classroom (although it's still worthwhile to encourage good reading habits, too). 14. Amusing Ourselves to Death From the author of Teaching as a Subversive Activity comes a sustained, withering and thought-provoking attack on television and what it is doing to us. Postman's theme is the decline of the printed word and the ascendancy of the "tube" with its tendency to present everything, murder, mayhem, politics, weather as entertainment. The ultimate effect, as Postman sees it, is the shriveling of public discourse as TV degrades our conception of what constitutes news, political debate, art, even religious thought. Early chapters trace America's one-time love affair with the printed word, from colonial pamphlets to the publication of the Lincoln-Douglas debates. There's a biting analysis of TV commercials as a form of "instant therapy" based on the assumption that human problems are easily solvable. Postman goes further than other critics in demonstrating that television represents a hostile attack on literate culture. 15. Fast Food Nation On any given day, one out of four Americans opts for a quick and cheap meal at a fast-food restaurant, without giving either its speed or its thriftiness a second thought. Fast food is so ubiquitous that it now seems as American, and harmless, as apple pie. But the industry's drive for consolidation, homogenization, and speed has radically transformed America's diet, landscape, economy, and workforce, often in insidiously destructive ways. Eric Schlosser, an award-winning journalist, opens his ambitious and ultimately devastating exposé with an introduction to the iconoclasts and high school dropouts, such as Harlan Sanders and the McDonald brothers, who first applied the principles of a factory assembly line to a commercial kitchen. Quickly, however, he moves behind the counter with the overworked and underpaid teenage workers, onto the factory farms where the potatoes and beef are grown, and into the slaughterhouses run by giant meatpacking corporations. Schlosser wants you to know why those French fries taste so good (with a visit to the world's largest flavor company) and "what really lurks between those sesame-seed buns." 16. Confessions of a Knife Merging art and religion with science, these largely autobiographical essays delve deeply into the emotional territory of medicine commonly avoided by other writers. This collection, first published in 1979, utilizes the physical body as a means to explore the human mind and soul. Never hesitant to admit his own frailties, Selzer draws readers a first-hand glimpse into the medical world. 17. Against Interpretation First published in 1966, this celebrated book--Sontag's first collection of essays--quickly became a modern classic, and has had an enormous influence in America and abroad on thinking about the arts and contemporary culture. As well as the title essay and the famous "Notes on Camp," Against Interpretation includes original and provocative discussions of Sartre, Simone Weil, Godard, Beckett, science-fiction movies, psychoanalysis, and contemporary religious thinking. This edition features a new afterword by Sontag. 18. The Plug-in Drug How does the passive act of watching television and other electronic media-regardless of their content-affect a developing child's relationship to the real world? Focusing on this crucial question, Marie Winn takes a compelling look at television's impact on children and the family. Winn's classic study has been extensively updated to address the new media landscape, including new sections on: computers, video games, the VCR, the V-Chip and other control devices, TV programming for babies, television and physical health, and gaining control of your TV.

Fiction Descriptions: 1. The Ultimate Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (includes all books in the series) Arthur Dent is introduced to the galaxy at large when he is rescued by an alien friend seconds before Earth's destruction. Then in The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, Arthur and his new friends travel to the end of time and discover the true reason for Earth's existence. In Life, the Universe, and Everything, the gang goes on a mission to save the entire universe. So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish recounts how Arthur finds true love and "God's Final Message to His Creation." Finally, Mostly Harmless is the story of Arthur's continuing search for home, in which he instead encounters his estranged daughter, who is on her own quest. 2. The Handmaid’s Tale In the Republic of Gilead, formerly the United States, far-right Schlafly/Falwell-type ideals have been carried to extremes in the mono-theocratic government. The resulting society is a feminist's nightmare: women are strictly controlled, unable to have jobs or money and assigned to various classes: the chaste, childless Wives; the housekeeping Marthas; and the reproductive Handmaids, who turn their offspring over to the "morally fit" Wives. The tale is told by Offred (read: "of Fred"), a Handmaid who recalls the past and tells how the chilling society came to be. This powerful, memorable novel is highly recommended for most libraries. 3. Fahrenheit 451 In Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury's classic, frightening vision of the future, firemen don't put out fires--they start them in order to burn books. Bradbury's vividly painted society holds up the appearance of happiness as the highest goal--a place where trivial information is good, and knowledge and ideas are bad. Fire Captain Beatty explains it this way, "Give the people contests they win by remembering the words to more popular songs.... Don't give them slippery stuff like philosophy or sociology to tie things up with. That way lies melancholy." 4. Digital Fortress In most thrillers, "hardware" consists of big guns, airplanes, military vehicles, and weapons that make things explode. Dan Brown has written a thriller for those of us who like our hardware with disc drives and who rate our heroes by big brainpower rather than big firepower. It's an Internet user's spy novel where the good guys and bad guys struggle over secrets somewhat more intellectual than just where the secret formula is hidden--they have to gain understanding of what the secret formula actually is. 5. Brave New World "Community, Identity, Stability" is the motto of Aldous Huxley's utopian World State. Here everyone consumes daily grams of soma, to fight depression, babies are born in laboratories, and the most popular form of entertainment is a "Feelie," a movie that stimulates the senses of sight, hearing, and touch. Though there is no violence and everyone is provided for, Bernard Marx feels something is missing and senses his relationship with a young women has the potential to be much more than the confines of their existence allow. Huxley foreshadowed many of the practices and gadgets we take for granted today--let's hope the sterility and absence of individuality he predicted aren't yet to come. 6. Getting Home Alive A mother and daughter of Puerto Rican and Jewish ancestry, the Moraleses express their radical and feminist views in diary-like poetry and prose that echo the rhetoric of the '60s. Yet the mixed origins of this pair lend an international, even universal feeling to the sentiments. They seem to speak for many women of many places and times. 7. One True Thing The book is a mother-daughter tale that has a deep feel for the way children often discover, just before it's too late, who their parents really are. "Our parents are never people to us," Ellen writes, "they're always character traits.... There is only room in the lifeboat of your life for one, and you always choose yourself, and turn your parents into whatever it takes to keep you afloat." The mercy-killing subplot isn't gripping, but the palpable sense of deepening family intimacy certainly is. 8. Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim Based on the author's descriptions, nearly every member of his family is funny, although some (like sister Tiffany, perhaps) in a tragic way. In "The Change in Me," Sedaris remembers that his mother was good at imitating people when it helped drive home her point. High-voiced, lovably plain-spoken brother Paul (aka The Rooster, Silly P) has long been a favorite character for Sedaris readers, though Paul's story takes on a serious note when his wife has a difficult pregnancy. The author doesn't shy away from embarrassing moments in his own life, either, including a childhood poker game that strays into strange, psychological territory. 9. Slaughterhouse Five Kurt Vonnegut's absurdist classic Slaughterhouse-Five introduces us to Billy Pilgrim, a man who becomes unstuck in time after he is abducted by aliens from the planet Tralfamadore. In a plot-scrambling display of virtuosity, we follow Pilgrim simultaneously through all phases of his life, concentrating on his (and Vonnegut's) shattering experience as an American prisoner of war who witnesses the firebombing of Dresden. 10. Optimist’s Daughter The optimist in question is 71-year-old Judge McKelva, who has come to a New Orleans hospital from Mount Salus, Mississippi, complaining of a "disturbance" in his vision. To his daughter, Laurel, it's as rare for him to admit "self-concern" as it is for him to be sick, and she immediately flies down from Chicago to be by his side. The subsequent operation on the judge's eye goes well, but the recovery does not. He lies still with both eyes heavily bandaged, growing ever more passive until finally--with some help from the shockingly vulgar Fay, his wife of two years--he simply dies. Together Fay and Laurel travel to Mount Salus to bury him, and the novel begins the inward spiral that leads Laurel to the moment when "all she had found had found her," when the "deepest spring in her heart had uncovered itself" and begins to flow again. 11. The Shadow of the Wind The time is the 1950s; the place, Barcelona. Daniel Sempere, the son of a widowed bookstore owner, is 10 when he discovers a novel, The Shadow of the Wind, by Julián Carax. The novel is rare, the author obscure, and rumors tell of a horribly disfigured man who has been burning every copy he can find of Carax's novels. The colorful cast of characters, the gothic turns and the straining for effect only give the book the feel of para-literature or the Hollywood version of a great 19th-century novel.