Report of the Interdisciplinary Advisory Council 2013-2014

The Interdisciplinary Advisory Council (IAC) is chaired by Carolyn Haynes, associate provost, and it includes representatives from each academic division and the University Libraries: Bob Applebaum, Michael Bailey-Van Kuren, H. Louise Davis, Peg Faimon, Tim Greenlee, Katie Johnson, Kate Kuvalanka, Chris Myers, Glenn Platt, and Jen Waller. During the 2013-2014 academic year, the IAC met ten times. Below are the Council mission, goals and progress steps since the data of the last report (November 2012). Council Mission The Interdisciplinary Advisory Council works with faculty members and administrators from Miami University’s six academic divisions to instigate and facilitate interdisciplinary research, collaboration, and instruction. The IAC is additionally responsible for: Advancing greater understanding of interdisciplinarity among faculty, students, staff and external partners;

Promoting interdisciplinary approaches to the curriculum, pedagogy and scholarship, and actively seeking new partners interested in interdisciplinary endeavors;

Providing a forum for faculty and administrators interested in interdisciplinary activities to network, share ideas and collaborate on projects of mutual interest

Collaborating with deans, department chairs and program directors to overcome obstacles to interdisciplinary teaching and scholarship

Forging structural changes to advance and generate interdisciplinary collaborations and activities, including new appointments, promotion, and tenure guidelines, rewards and recognition, evaluation and assessment processes, appropriate data collection, hiring procedures, and resource allocations.

Partnering with the university development office to create strategies for interdisciplinary program fundraising.

Advocating interdisciplinary programs to the Miami community and external organizations.

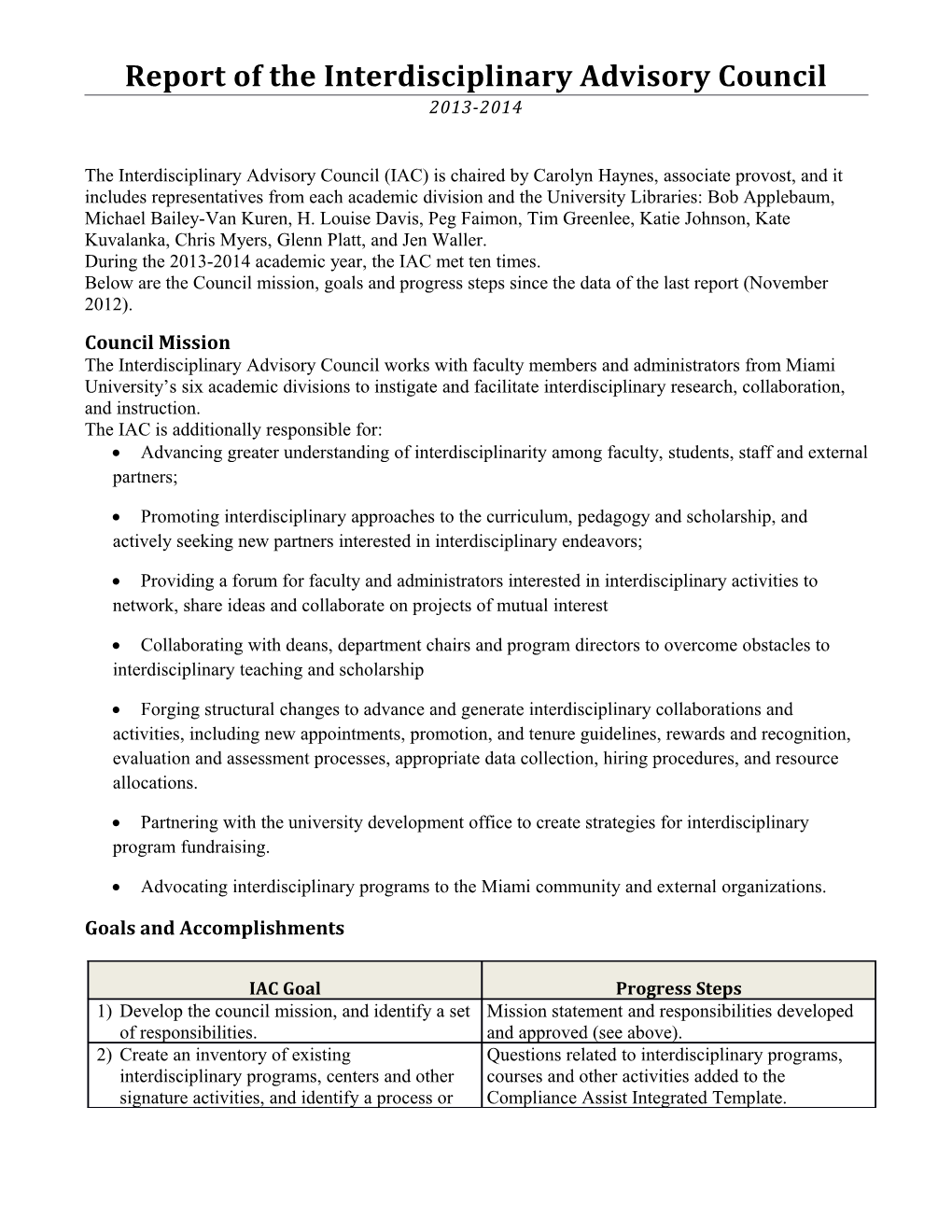

Goals and Accomplishments

IAC Goal Progress Steps 1) Develop the council mission, and identify a set Mission statement and responsibilities developed of responsibilities. and approved (see above). 2) Create an inventory of existing Questions related to interdisciplinary programs, interdisciplinary programs, centers and other courses and other activities added to the signature activities, and identify a process or Compliance Assist Integrated Template. 2

processes for accurately recording the divisional, departmental and individual faculty contributions for interdisciplinary courses. 3) Communicate with the Miami Plan Redesign Two IAC members served on the Miami Plan Team and the leadership of the Top 25 Redesign team , and one member served on the initiative about the possibility of including Liberal Education Council. They were able to interdisciplinary learning in the new general encourage the inclusion of the integrative learning education program and existing foundation competency as well as a new experiential learning courses. requirement in the new Miami Plan redesign effort. 4) Develop a consistent policy for the cross- New guidelines developed, vetted with listing of courses and procedures for interdisciplinary program directors, revised, and developing new subject codes or prefixes for approved by Academic Policy Committee, COAD courses. and Senate in fall 2013. See Appendix A. 5) Define the various models of team-teaching, Team-teaching guidelines developed, shared with and develop a rubric or some other mechanism interdisciplinary program directors, revised, and for appropriately assessing and recognizing the shared with individual deans. Revised guidelines contributions of instructors engaged in team were submitted to and approved by COAD in fall teaching. 2013. See Appendix B. 6) Create a website for interdisciplinary teaching, Purpose, goals, and intended audience for website learning, and research at Miami. developed; content and site was launched in October 2013. See: www.miamioh.edu/oue 7) Launch “i-Network” which is aimed at faculty Kick-off event held in November 2013 with over and administrators interested in 40 faculty members in attendance. A list of ideas, interdisciplinary teaching, learning and barriers, and suggested steps for improving scholarship. interdisciplinary learning at Miami was developed. See Appendix C for summary of ideas generated at the event. 8) Hold workshop for new and continuing Workshop held in February 2014. See Appendix faculty to introduce them to resources for D for workshop agenda. interdisciplinary teaching and research and to forge cross-departmental and cross-divisional partnerships. 9) Create suggestions for supporting Four documents drafted in spring 2014: interdisciplinary faculty which can be used by Suggestions for supporting department chairs and deans. interdisciplinary tenure track faculty; Suggestions for supporting interdisciplinary senior faculty; Suggestions for supporting interdisciplinary LCPL faculty; Suggestions for publishing and evaluating interdisciplinary scholarship. See Appendices E-H. 3

Appendix A: Cross-Listing Courses Policy

Rationale A cross-listed course is the same course catalogued under two or more prefixes (also known as subject codes). Cross-listing of courses can provide faculty an opportunity to collaborate across disciplinary and departmental lines, and it offers students the opportunity to engage in multidisciplinary, cross- disciplinary and interdisciplinary learning. Cross-listing may also benefit departments and programs through the sharing of resources and ideas. Although Miami University has been cross-listing courses for many years, no policy or procedures have been articulated to guide the creation and implementation of cross-listing. In this document, we offer suggested guidelines for cross-listing courses which we hope will sustain its key benefits yet also address some of its limitations. Below are some of the challenges currently faced with cross-listing courses: 1. Not only has the number of cross-listed courses increased over time, but the various types of cross-listings have increased. For example, although the majority of courses carry two prefixes, other cross-listed courses have accumulated many more prefixes. One course, for example, holds ten different prefixes. In courses when there are numerous prefixes, some of the cross- listed portions of the course have few or no students. To complicate the situation further, some cross-listed courses carry not only different prefixes but also different numbers, including different levels of numbers, such as a 200-level course cross-listed with a 300-level course. This situation is confusing for students and cumbersome for book-keeping purposes. Courses with different numbers diminish the message that different course levels signify different levels of learning. 2. Because Banner only allows one portion of the cross-listed course (one prefix and number) when students register, courses can appear full when they are not. Similarly, courses can appear under- enrolled when they are not. This situation is confusing for students and challenging for administrators who must handle queries relating to the enrollments of a cross-listed course. 3. With the addition of each prefix, the complexities of encoding the degree audit add significant administrative workload for academic administrators, both within the academic divisions and the Office of the Registrar. Significant time and energy are expended to: build each new course in Banner; reconfigure the degree paths of all affected majors, minors, and thematic sequences; set enrollment caps for each cross-listed section; and align the schedules from all participating departments and programs. As the University continues to reduce the size of its staff and faculty, the need to advance efficiency is even more imperative. These challenges have propelled us to consider ways of improving the way that we cross-list courses. A new set of recommended guidelines for cross-listing may also be benefited by two initiatives that are underway. First, Miami is moving to the Responsibility Centered Management (RCM) budgeting approach. Under RCM, cross-listing and departmental designations of courses in general are not as relevant because the RCM revenue-generation formula for courses is based upon the divisional location of the instructor’s salary line and the division where the enrolled student’s “first or primary” major is located. It is not based upon the departmental subject or designation(s) of the course. Thus, departments may not feel a need to have their subject code or prefix tied to as many courses as possible, since resources are not dependent upon the subject code of the course. Second, in the past, departments and programs may have wanted their prefix or subject code attached to a course because it would make the course more visible to students when they registered for courses. Beginning in 2013-2014, Miami students will have access to a new interactive degree-planning software 4 program, called u.Direct, which will enable them to more readily plan their path to graduation and to see all of the possible courses (and descriptions of those courses) for meeting different degree requirements on a term-by-term basis. u.Direct enables students to see major related courses, courses outside of their home department as well as their relevance to their degree plans much more easily and all on one screen.

Recommended Guidelines for Cross-Listing Courses The goal of this proposal to provide guidance for the cross-listing of courses and to address the challenges articulated above. Cross-listing should be done more purposefully and sparingly to indicate a true overlap of disciplinary foundations. Since Responsibility Centered Management policies imply that cross-listing no longer has resource implications, the following policy is advanced both to clarify the interdisciplinary nature of course content and to simplify the registration process. 1. Students may only earn credit for the same course under one prefix. If the course is repeatable for credit, students may only retake the course under the same prefix as the previous attempt. Students may sign up under any prefix of a cross-listed course (except if it is being repeated for credit), but they may be advised according to academic program requirements (where applicable).

2. Cross-listed courses and proposals must be identical in title, prerequisites, description, credits, grading practice, meeting times and days, and number of times a course may be taken for credit. When possible the cross-listed courses should carry the same course number.

3. Permanent courses should not be cross-listed with special topics or temporary courses under other prefixes.

4. Cross-listed courses should only be cross-listed with courses at the same level. For example, MTH 2XX should not be cross-listed with PHY 3XX. The cross-listing of 400/500 courses is an obvious exception.

5. Each course description in the Bulletin and on u.Direct should end with: "Cross-listed with [prefix]."

There will be a limit of three or fewer prefixes for cross-listed courses.1 Exceptions to the three-prefix limit will be made in unique circumstances where the petitioners can offer a compelling reason for additional prefixes beyond three. For example, the foundations of four disciplines are all represented in a significant part the course content and a rationale for why an existing or new single prefix (see below) would not be appropriate. The litmus test for this exception is whether the course would have been offered in each of the cross-listing programs, as written, without any participation from the other

1 A review of currently cross-listed courses indicates that 70% of cross-listed courses presently have only two prefixes. Of the remaining 30%, a significant majority of those cross-listings were either from: a) the biological sciences which recently merged to create a single prefix; b) graduate/undergraduate cross-listing (which is exempt from this policy); or c) honors or other “modifiers” (which do not apply to this policy). We also reviewed the cross-listing policies and practices of 30 other universities. Over 80% limit the number of prefixes to two, and the remaining institutions limit cross-listing prefixes to three. 5 programs. The University Registrar, in consultation with the Office of the Provost and the Interdisciplinary Advisory Council, will review petition requests.

In general, new and existing interdisciplinary programs are encouraged to create (if they don’t have one) and use (if they have one) their own subject code on courses they offer, rather than cross-list. (See proposed guidelines for creating subject codes or prefixes.) Courses that are not part of an academic program but have contributions from more than two departments or program may use the divisional prefix (e.g., CAS, EHS, EAS, BUS, SCA) if they are drawing from perspectives within the division. For courses that are not part of any academic program and draw from departments and programs in different schools or colleges, a new university-level prefix (such as MUI) should be created and used for that purpose. Cross-listed courses, including, but not limited to those with more than three prefixes, are encouraged to adopt the university prefix for ease of course registration and for clarification of the unique university-wide content.

Note: These guidelines will be instituted in AY2014-2015 to provide time for departments and programs to work with the Registrar to adjust existing course prefixes and numbers accordingly and to alter appropriate University publications and websites. 6

Appendix B: MODELS OF TEAM-TEACHING Katie Johnson and Peg Faimon on behalf of the Interdisciplinary Advisory Council Revised March 29, 2013 Interdisciplinary, team-taught courses have for some time been lauded for their innovation and efficacy. Scholars such as Carolyn Haynes, William Newell, Julie Klein, and Tanya Augsburg, among others, have shown the power of advancing knowledge with team-taught pedagogies.i Given that research has compellingly demonstrated that both students and faculty benefit from team-teaching, we recommend that Miami supports team-teaching in various modes. The paths to interdisciplinary collaboration and team teaching are many, as James Davis notes in Interdisciplinary Courses and Team Teaching.ii Indeed, there is a continuum of collaboration in team teaching that involves various levels of engagement in the planning, content integration, teaching, and evaluation of courses. To that end, we have identified eight possible models for team teaching, but there certainly could be more. We offer this document as a way to invite campus-wide pedagogical innovation. Suggestions for assessment and support can be found on the attached grid. 1) Connected Team-Taught Courses in which two or more faculty teach two or more different course numbers (e.g. Highwire Brand Studio, ART 453 & MKT 442) at the same time and in the same room for the entire semester. The faculty and students collaborate on the same content/project(s) for the entire semester, and the faculty collaboratively design and teach the course content and evaluate student work.

2) Partially Connected Team-Taught Courses in which two or more faculty teach two or more different course numbers [OR the same course numbers] that work together for a portion of the semester. This arrangement may involve, for instance, a unit where classes come together to work on a project or study a related topic.

3) Conventional Team-Taught Courses where two or more faculty teach the same course number (IMS 440 or WST 301) together for the entire semester. The course is collaboratively designed, taught, and graded, and both instructors are physically present in the classroom for the entire term. The instructors collaborate on all of the work for the course.

4) Relay-Race Team-Taught Courses in which two or more faculty teach the same course, but they are not physically in the classroom together at the same time. Instead, one instructor hands off leading the course to another, much like passing a baton in a relay- race. Faculty still must coordinate their content to make sure it is cohesive and complementary within the structure of the course, but they do not actually share the teaching or grading.

5) Splash Team Teaching with Lead Faculty with Supplemental Instructors in which one or more “lead” faculty has primary responsibility for teaching the course, and supplemental faculty teach one or two class sessions and/or act as support or resource instructors for such targeted activities as critiques, workshops, or juries. 7

6) On and Off Multiple Sections. In this case, multiple instructors teach multiple sections of the same course, and they might come together for parts of the course to share guest speakers, presentations, or projects.

7) Team Teaching with a Faculty from Another Institution. In this case, you might have various arrangements, depending on the needs and situation.

8) Nontraditional Team Teaching which may occur outside the classroom, in learning communities, in spaces and places not yet imagined. For example, Miami could initiate a learning experience like Evergreen College’s “Fields of Study,” which are team-taught, interdisciplinary “programs” in Coordinated Study that last an entire semester. http://admissions.evergreen.edu/curriculum i See, for example: Augsburg, Tanya. Becoming interdisciplinary: An introduction to interdisciplinary studies. Kendall/Hunt Pub., 2006; Haynes, Carolyn, ed. Innovations in Interdisciplinary Teaching. Westport, CT: Oryx/Greenwood Press, 2003; Klein, Julie T. Interdisciplinarity: History, Theory, and Practice. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1990; Newell, William H. , “Powerful pedagogies.” In Reinventing Ourselves: Interdisciplinary Education, Collaborative Learning, and Experimentation in Higher Education, ed. B.L. Smith and J. McCann, 196–211. Bolton, MA: Anker Press, 2001.

ii Davis, James. R. 1995. Interdisciplinary courses and team teaching: New arrangements for learning. Phoenix, AZ: Anker.

Appendix C: i-Network Kickoff Meeting November 4, 2013; 5:30 – 7:00 pm; Marcum Conference Center The Interdisciplinary Advisory Council hosted a kick-off reception and event for all faculty interested in pursuing interdisciplinary teaching and learning opportunities. Participants were asked to discuss the following three topics in small groups: 1. What is your vision for a highly integrative, interdisciplinary learning environment? What are the key elements? 2. What do you see as some of the challenges and barriers that we face which might prevent or impede this vision? 3. What are some next steps that the IAC could take to move toward this vision? Below is a summary of the responses generated to the above questions.

Vision of a Highly Integrative, Interdisciplinary University Flexible and open spaces for shared learning and collaborations; problem-based spaces that are not controlled by a program or department Mutual respect and understanding across divisions, departments, disciplines, fields Ongoing interdisciplinary conversations Broad perspectives, such as being in the Grand Canyon and not focusing only on the bug you are crushing Willingness to look outward Focus on coordinated, flexible, integrative learning versus traditional silos Promotion of studio model learning Advancement of student-centered learning over teacher-centered learning Faculty offices not assigned by department or discipline but by interest area; or randomly assigned faculty offices to encourage unexpected results Open lines of communication “Idea Kitchens” that are open to all Technology leveraged to advance cross-disciplinary inquiries and communications More focus on integrative learning and less focus on specialization of knowledge Interdisciplinary scholarship, experiential learning, and risk-taking are encouraged and rewarded. Faculty café time or faculty club; gathering spaces that allow cohesion Finding time for building networks and relationships and experimenting with new ways of thinking Playfulness and happenstance Students navigate multiple disciplinary cultures every semester Culture where we embrace borrowing, stealing, appropriating ideas Coordinated studies and open time blocks for learning Learning communities Problem-based networks Focus on methodologies rather than disciplines and departments Cross-divisional partnerships and work Cross-listing Heterogeneous learning outcomes Team teaching across disciplines Integrative projects that are experiential, research-oriented, community based Self-defined degree paths Students are exposed and excited by interdisciplinary thinking early in their undergraduate experience Multiple models of liberal education

Barriers & Challenges Physical spaces that isolate students and faculty by department or division Few clear rewards for interdisciplinary activity Exam based culture and standardized assessment instruments Fear of change and the unknown Inadequate funding and resources RCM budgeting model that can be divisive and breed “silos” and turf wars among divisions Over emphasis of budgetary matters over intellectual ideas Inability to see connections among global understanding, interdisciplinary studies and community/service learning Worries about one’s ability to do interdisciplinarity: Can we teach interdisciplinary courses without knowing interdisciplinary theory? How easy is it to teach interdisciplinary skills and outcomes? What does the map toward interdisciplinarity look like? Is it too difficult to foster interdisciplinary work among undergraduates since they don’t have the disciplinary knowledge base yet? Miami Plan does not encourage interdisciplinarity; CAS requirements also do not encourage interdisciplinarity Parents, students, employers may not see relationship of interdisciplinarity to employment and professional success Lots of myths surround interdisciplinarity. For example, some people think that one person cannot be interdisciplinary or that interdisciplinarity can only be done via team teaching. Mental and Physical Silos Finding balance between depth of learning (disciplines) and breadth (interdisciplinarity) University system privileges uniformity Professional accreditation (e.g., ABET) privileges disciplinarity Scaling interdisciplinarity is challenging Different discourses among departments, disciplines make finding common ground challenging We are in the “habit” of disciplinary thinking and ways of operating The competing perceptions that interdisciplinarity always leads to cost-saving or that it is too costly The idea that interdisciplinarity is opposed to disciplinarity when in fact the relationship is synergistic Doing good interdisciplinary work is time-consuming and can be more difficult for faculty Faculty workload is high, leaving little time for experimentation

Next Steps Create incentives in the form of rewards and recognition for faculty, programs and “frontier” or pioneering activities—e.g., team-teaching, interdisciplinary projects, newly designed pioneering interdisciplinary courses Create “safe zones” that allow or even encourage risks and failure, such as new evaluation mechanisms that reward risk-taking and innovation Find ways to ease cross-divisional enrollment barriers Facilitate teaching and research clusters of faculty; clusters could focus on common themes, rather than disciplines Create grants for interdisciplinary work Advocate for physical spaces that encourage interdisciplinary learning—perhaps in the library Review P&T and merit evaluation criteria, and revise to support interdisciplinary work. For example, create a committee of “experts” who understand interdisciplinary work and who can provide external reviews on P&T dossiers Create an option for team office suites where faculty may be grouped for a period of time by a common interest area. Educate faculty on interdisciplinarity and its relationship to other pedagogical and curricular approaches. Work toward a more common understanding of interdisciplinary (term is often used too loosely and confused with other terms such as multidisciplinarity, transdisciplinarity, cross-disciplinarity, etc.); promote the idea of interdisciplinarity as a means to addressing questions or solving problems rather than an end in itself Set up Intra-Miami Google or Facebook Group Provost and Provost could send messages about importance of interdisciplinarity Design exciting interdisciplinary programs which are attractive to students Establish problem-based networks Launch faculty cluster hires around themes, common interests Encourage or require interdisciplinary and team-taught capstones and first-year seminars Review teaching evaluations and revise to encourage interdisciplinarity, risk-taking, creativity Dedicate part of e-news to faculty ideas to encourage connections Set aside one time period when no classes are held to foster common activities and collaborations Revise activity reports to include categories related to interdisciplinarity, risk-taking, etc. Incorporate intentional interdisciplinary learning in Miami Plan (team teaching, etc.) Clearly explain RCM and its implications for interdisciplinarity to faculty so that people are informed Hold more networking events to develop strategic partnerships

Appendix D: Agenda for Workshop on Interdisciplinary Teaching & Scholarship for New Faculty February 6, 2014; Marcum Conference Center, 5:00-7:00 pm

5:00 pm Meet & Greet 5:20 pm Welcome Brief Explanation of IAC and Introduction of Members (Carolyn Haynes) Overview of Goals of the Workshop Promotion & tenure and interdisciplinarity (Kimberly Hamlin) 5:50 pm Interdisciplinary Teaching or Research Activity Guidelines

Interdisciplinary Teaching Activity Your group will engage in some boundary-crossing curricular brainstorming. Try to suspend your particular teaching concerns and to involve yourself in some intellectual bridge-building with your colleagues. Your group should appoint one person to serve as a facilitator who will act as the “scribe” and “timekeeper.”

INTRODUCTIONS Move around the table and introduce yourself. Introductions should include: Name Department/Program Disciplinary/Interdisciplinary Degrees Teaching and Research Interests Other Interests (Hobbies, Side Interests)

CHOOSING A COURSE FOCUS Imagine that your group must come together to develop an interdisciplinary course that incorporates the knowledge, interests or side interests of the people at this table. See if you can come to consensus on any common theme, question, or topic that could conceivably be the organizing idea for the course. If group members’ views are widely divergent, after a few minutes, take a leap of faith and settle on one of the focal ideas with which everyone feels somewhat comfortable working in this setting.

BRAINSTORMING NEW IDEAS Note: The facilitator should write down ideas on the flip chart paper so that everyone can see them. Given an imaginary semester in which your group members were teaching collaboratively around this theme, what might you and your students do? What might be some of the subthemes and learning objectives? Assignments? Texts and/or authors? Films or videos? Field or other experiential activities? Generate as many ideas for this course as you can. Try not to pause to judge or discuss the fine points or merits of each suggestion. Resist the temptation to discuss whether such a course is feasible in our university setting. Instead generate as many ideas as you can. Interdisciplinary Research Activity Your group will engage in some boundary-crossing scholarly brainstorming. Try to suspend your particular scholarly or research concerns and to involve yourself in some intellectual bridge-building with your colleagues. Your group should appoint one person to serve as a facilitator who will act as the “scribe” and “timekeeper.”

INTRODUCTIONS Move around the table and introduce yourself. Introductions should include: Name Department/Program Disciplinary/Interdisciplinary Degrees Teaching and Research Interests Other Interests (Hobbies, Side Interests)

CHOOSING A RESEARCH FOCUS Decide as a group to generate a proposal to conduct a pioneering interdisciplinary research or creative project that draws upon the expertise and interests of the people at your table. See if you can come to consensus on any common problem, question, or topic that could conceivably be the organizing idea for the project. If group members’ views are widely divergent, after a few minutes, take a leap of faith and settle on one of the focal ideas with which everyone feels somewhat comfortable working in this setting.

BRAINSTORMING NEW IDEAS Note: The facilitator should write down ideas on the flip chart paper so that everyone can see them. What interdisciplinary question or problem would your project be addressing? Which disciplines or subdisciplines would you draw upon? What method or methods might you use to address the question or problem? Where would you go to find the data or information you need? What challenges might you face in working across these different disciplines and fields? What strategies might you use to reach common ground among the different disciplines/fields or synthesize information and knowledge? What outcomes might you anticipate from this project?

Generate as many ideas for this project as you can. Try not to pause to judge or discuss the fine points or merits of each suggestion. Resist the temptation to discuss whether such a project is feasible in our university setting. Instead generate as many ideas as you can.

6: 20 pm Sharing of Course and Project Ideas

6:40 pm Interdisciplinary Opportunities and Resources at Miami (Guest Panel) Facilitator will encourage faculty to utilize the website and brochure for additional information. Facilitator will introduce a panel consisting of administrators who can offer insights on how to become more involved in their center/program. Examples: Jim Oris to explain grant opportunities (Get similar person on regional campus) Cecilia Shore to explain CELTUA opportunities (Get similar person on regional campus) Interdisciplinary center directors (1-2) (will vary depending on campus) Interdisciplinary program directors (2-3) (will vary depending on campus)

Appendix E: Suggestions for Advancing the Success of Interdisciplinary Tenure-Track Faculty NOTE: THESE SUGGESTIONS ARE DESIGNED TO COMPLEMENT EXISTING MIAMI UNIVERSITY POLICIES AND INFORMATION. NONE OF THE SUGGESTIONS IN THIS DOCUMENT SUPERSEDE UNIVERSITY POLICIES AND PROCEDURES.

Introduction This document provides suggestions for probationary tenure-track faculty interested in pursuing interdisciplinary work and for administrators (department chairs, program directors, deans) working with faculty who are pursuing interdisciplinary teaching and research. It provides suggestions for better ensuring the professional success and retention of interdisciplinary faculty. It includes ideas for faculty who were originally hired to do interdisciplinary work as well as faculty who might have developed an interest in interdisciplinary work after being hired. Since 1997, three ad hoc committees have been developed which offered specific and similar recommendations on advancing an interdisciplinary culture at Miami University: the 1997 “Ways to Encourage Interdisciplinary Teaching”; the 2006 “Report of the First in 2009 Coordinating Council Sub-Committee on Interdisciplinarity at Miami University”; and the 2011 Interdisciplinary Enhancement Committee Report. Each report identified the barriers to interdisciplinary work, the landscape of interdisciplinary activity at Miami at the time, perspectives from various stakeholders around campus, and key recommendations for how to enhance and encourage interdisciplinarity. The cornerstone of the 2006 report was a campus-wide survey that gathered data about barriers to interdisciplinary teaching and research. An open meeting for Miami faculty and administrators, which was held in November 2013 and sponsored by the Interdisciplinary Advisory Council, also yielded similar recommendations on fostering an interdisciplinary teaching and research environment at Miami. Findings from the November 2013 meeting and the previous committee reports as well as best practices gleaned from the professional literature have shaped the recommendations and ideas embedded in this document. Interdisciplinary Studies Today Colleges and universities are experiencing a marked increase in interdisciplinary research and education. As one researcher noted, for the past ten years, “interdisciplinary programs have multiplied at a dizzying pace” (Nowacek, 2009, 493), with “over half of current general education reforms includ[ing] interdisciplinary programs or courses” (494). Likewise, the National Academy of Science, the National Academy of Engineering, the National Science Foundation, and the Institute of Medicine have extolled the benefits of interdisciplinary research and taken steps to promote its expansion (National Academies Press, 2004; see also http://www.nsf.gov/od/oia/additional_resources/interdisciplinary_research/). Similarly, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Council of Learned Societies, and the Social Science Research Council have also recently developed and prioritized prominent interdisciplinary initiatives. Understanding the Benefits and Challenges of Interdisciplinary Faculty As summarized in the table below, faculty who engage actively in interdisciplinary teaching, scholarship, and service opportunities provide significant benefits and challenges for the University. Benefits Challenges Teaching Focuses on exciting and cutting-edge subjects or topics Thematic focus can be appealing to students Team-teaching can promote faculty development, teaching excellence, and collaborations Often involves experiential learning (e.g., field experiences, service learning, collaborative learning) No or few textbooks Lack of sample syllabi or longstanding models to follow No clear body of knowledge to cover Team-teaching, due to its collaborative nature and the need for the instructors to learn new disciplines, can be more time-consuming Students and parents may not immediately perceive value Assessment methods may be unique Research Can be ground-breaking, pioneering Encourages a more holistic or comprehensive approach to learning Can appeal to major funding agencies Often involves collaborations across departments, divisions, or institutions Often involves social issues Lack of recognition by established scholars Lack of sustained funding opportunities Lack of familiarity with reputable journals and publication outlets Lack of peer reviewers and mentors Career trajectory less clear Extended start-up time Not as many honors as in disciplinary fields Can wrongly be considered less rigorous Requires time to cultivate and maintain Service Fosters community connections Builds bridges between disciplines, departments, divisions Enables faculty to become known on campus Multiple and competing demands and priorities Jointly appointed faculty serve two or more academic departments or programs; each department may not recognize the service demands required from the other Promotion & Tenure Broadens network for reviewers and for the department and University Procedures & criteria may be biased toward disciplines Reviewers may assume disciplinary norms or standards

Robert Clark, Dean of the Pratt School of Engineering at Duke University, writes, It is clear that research and teaching “at the boundaries of traditional . . . disciplines [are] yielding tremendous gains. . . The simple act of brainstorming in a group of faculty having different backgrounds is tremendously exciting and stimulating. Such groups diminish the fear associated with suggesting ideas that are outside the accepted ‘dogma’ of a particular researcher’s discipline. There is less risk of being criticized by colleagues that understand when you approach the problem with a different background and perspective. As a result, this kind of brainstorming among colleagues from different disciplines can stimulate creativity, sometimes leading to radically unique ideas or approaches.”

Although supporting interdisciplinary research and teaching comes with challenges-- including ensuring administrative flexibility and support, seed funding, and constant exposure to faculty in other disciplines to expand the vocabulary, which can vary greatly from discipline to discipline—it is worth the effort. Considerations for Interdisciplinary Faculty The scholarship and/or teaching of interdisciplinary faculty may not fit with established norms, criteria, resources, and rewards. Interdisciplinary faculty members approach their research and teaching in different ways, and each approach has somewhat different implications.

Considerations Related to Interdisciplinary Research Interdisciplinary faculty can work on interdisciplinary questions individually, bringing together information from different fields, or they can work in teams. Their projects frequently cross departments, and often involve applied problems with unusual stakeholders, outside of the academy. Interdisciplinary work comes in a variety of forms (Rhoten and Pfirman, 2007): (1) Cross-fertilization –adapting and using ideas, approaches and information from different fields and/or disciplines. (2) Team-collaboration—collaborating in teams or networks that span different fields and/or disciplines. (3) Field-creation--creating new spheres of inquiry that sit at the intersection or edges of multiple fields and/or disciplines. (4) Problem-orientation—addressing problems that engage multiple stakeholders and missions outside of academe, for example that serve society. Collaborative interdisciplinary research can sometimes involve higher networking costs. Colleagues often have different priorities, and it takes time to learn how to cross disciplinary language barriers. Time and energy are also required for identifying potential partners, maintaining contact with them, and writing and then revising multi-authored documents. If the collaborators are not at the same institution, support for travel can be vital. Seeing collaborators at meetings and/or visiting them in their home institutions are excellent ways to maintain connections and build recognition. Travel support for interdisciplinary scholars to attend meetings of a number of disciplinary groups is also helpful. As collaborative interdisciplinary projects evolve, junior scholars need to make clear their unique contributions. Interdisciplinary research projects frequently take a long time to get established and produce results, in part because of the networking required to bridge cultures and communities, but also because finding funding for interdisciplinary research can sometimes be a challenge. While there has been increasing attention to interdisciplinary scholarship in recent years, requests for proposals for interdisciplinary research may not be as predictable as RFP’s in the traditional disciplines. Because each funding source has its own traditions, it is hard to learn how to gain entry. Interdisciplinary research, particularly research that cuts across widely divergent disciplines and fields, can be difficult to publish in recognized journals. There are fewer journals that specialize in broadly interdisciplinary research and among the ones that do, impact factors vary greatly. Ideally the junior faculty member or researcher reserves publication of major innovations for highly respected - often disciplinary - journals that count more in promotion and tenure reviews. While interdisciplinary research is often published in conference proceedings or as book chapters, because these are not usually indexed in traditional ways, they mat be more difficult for other scholars to find, and therefore cite. An excellent way to highlight the significance of the faculty member’s interdisciplinary research, as well as to build research recognition, is for junior scholars to have the opportunity to invite speakers who are doing related work to campus. This helps other faculty, researchers, and students learn how the junior faculty member’s work fits into the larger field. If junior scholars host or co-host speakers, these guest visits will also provide mentoring opportunities for them. Another option for junior scholars to gain visibility is to host a special session at a professional meeting and become involved in professional societies. Encouraging junior scholars to apply for seed grant funding for interdisciplinary work can help them learn how to interact across disciplinary boundaries and articulate the value of proposed interdisciplinary work convincingly.

Considerations Related to Interdisciplinary Teaching Interdisciplinary teaching entails the use and integration of methods, concepts, and analytical frameworks from more than one academic discipline to examine a theme, issue, question, or topic. The hallmark of interdisciplinary education is integration of knowledge and guiding principles from multiple disciplines to systematically form a more complete, and hopefully coherent, understanding of the issue under examination. Interdisciplinary teaching activities may need additional support and development, particularly when the faculty member is involved in developing new courses that span multiple disciplines—often without a standard textbook or readily available teaching resources—or when the faculty member is piloting new experimental teaching approaches. Although there is no single preferred pedagogy or teaching approach for interdisciplinary courses, most interdisciplinary faculty are learning new fields of knowledge and advancing active forms of learning such as service learning, team-teaching, inquiry-based education, learning communities, or collaborative learning, which may take time, experience and professional development to master. Because of the unique nature of interdisciplinary teaching, teaching portfolios can be a dynamic and performance-based way for interdisciplinary faculty to demonstrate the product of their teaching efforts (e.g., Goldstein, 2006; DeZure, 2010) to their colleagues. Moreover, because the learning outcomes for interdisciplinary courses can differ from those advanced in disciplinary learning contexts, assessment measures may be unique and require significant time to develop. For more information on interdisciplinary teaching and assessment, see: http://miamioh.edu/oue/interdisciplinary/index.html. Additionally, the Center for the Enhancement of Learning, Teaching, and University Assessment can provide assistance on developing teaching portfolios.

Considerations Related to Service of Interdisciplinary Faculty Interdisciplinary faculty members may have a joint academic appointment, serve as an affiliate in a program or department, or be heavily involved in a center, institute, or major interdisciplinary initiative outside of their home department. As a result, the nature and extent of service (to the department, program, division, University, profession, community) may be more expansive and different from the service record of a faculty member who works within the confines of a single discipline, department, or division. It is important to recognize that because interdisciplinary programs, centers, and institutes have few (if any) core faculty assigned to them, they largely rely on the contributions of faculty whose lines exist in other departments or divisions. Consequently, the service the faculty members offer these units may at times be substantial.

Mentoring Tenure-Track Faculty It is essential to provide adequate mentoring to all junior faculty, but especially those whose research, service, and/or teaching areas are interdisciplinary. In particular, junior faculty and their chairs or directors should identify clear goals for what is expected. For example, they should not be surprised to learn, in their fifth year, that the department does not recognize some publication venues or certain forms of teaching or service as valuable for promotion or tenure. If a faculty member is heavily involved in a center or institute, it is especially important to provide advice about how to balance work on large team projects with work that establishes a strong individual reputation. For tenure-track faculty, having a mentor who has conducted interdisciplinary research can also be very useful. Mentors may be able to provide guidance in navigating funding. Somewhat paradoxically, while acquiring funding increasingly calls for interdisciplinary collaboration, most funding still comes from agencies that are known within individual disciplines. It may be necessary to provide two (or more) mentors to ensure coverage of the different areas in which the faculty member works. When establishing a mentoring relationship, it should be clear to all whether or not the mentor has a role in evaluating the junior person. Mentoring should include liaising with the department/program and where needed with upper-level administration to assure that the strategies described above are implemented appropriately. Moreover, chairs or directors as well as faculty may wish to consult senior interdisciplinary faculty or the Interdisciplinary Advisory Council for additional guidance on best practices. Coordinating the Evaluation Process for Tenure-Track Faculty Whether an interdisciplinary faculty member holds an appointment within a single department or holds a joint appointment, challenges may arise in the promotion/tenure evaluation within the department or division. The single greatest difficulty is that faculty members may judge other faculty according to the norms and criteria of their own discipline, and departments or divisions may believe that their approaches to research or teaching are the best ones. Even when faculty members conducting the evaluation within a given department or division adopt an open-minded stance, it may be challenging for them to calibrate the metrics for impact and academic success within another discipline. For example, when evaluating tenure-track faculty, faculty in some disciplines value conference papers highly while faculty in other disciplines do not. In addition to the need to evaluate the types of research products—books, journal papers, conference papers, artifacts, and so on—it is also critical to understand the quality of each product. Which conferences are important? Which awards carry the greatest prestige? Which people are the luminaries whose review letters should be taken most seriously, and which are known to be hypercritical? Which comments in a review letter are most relevant and which omissions are significant? Finally, if a faculty member is publishing in multiple areas, it is likely that some of the referees will only have knowledge of a portion of the member’s work. When evaluating teaching, questions may arise such as: What is the appropriate grade point average for particular types of courses/fields/disciplines? What teaching approaches are considered innovative or appropriate? What sort of qualitative comments on course evaluations should be heeded or ignored? How much credit should be given to a faculty member who has team-taught or team-designed a course? To address these concerns, the following recommendations are offered: If possible, involve people from relevant disciplines or interdisciplinary fields in the annual merit review and third-year review of the interdisciplinary faculty member. Similarly, in the evaluation of scholarship in the tenure-track faculty member’s promotion and tenure dossier, involve a faculty member with expertise in the other discipline(s) or interdisciplinary fields relevant to the faculty member’s interests. If the unit selects an ad hoc promotion and tenure committee for each candidate, then an interdisciplinary faculty member external to the department/program could be member of the committee. Be sure that the outside member plays a role in selecting the referees who will write letters evaluating the candidate. Also task that member with helping to make sure that the promotion and tenure committee itself, as well any faculty who will vote on the tenure case, understand the values and norms of those other participating discipline or the other interdisciplinary field. It may be helpful to write down metrics for judging academic success. Educate the promotion and tenure committee(s) on the standards of scholarship and research methodologies in the relevant disciplines or interdisciplinary fields. Familiarize committee members with ways of evaluating scholarship outside of one’s discipline. In requesting letters of recommendation, consider including wording that specifically asks the letter-writer to evaluate the candidate on the basis of his or her own area of expertise, while recognizing that the candidate has conducted interdisciplinary research. Anticipate that the dossier and process will take longer to prepare and evaluate than purely disciplinary cases, and plan accordingly. It may take more time to develop the dossier, select the promotion and tenure or evaluation committee, select the letter-writers, and evaluate the dossier.

Dossier Preparation One of the most important factors to keep in mind in preparing materials is clarification of the significance of the individual’s work. Because the dossier will be read by many people who do not have expertise in the teaching/research area(s) of the candidate, the candidate will need to present a narrative that explains his or her development as an interdisciplinary faculty member (Austin, 2003). For example, because many reviewers of interdisciplinary faculty will not be familiar with all the journals, the dossier could be annotated with information on journal standing, and reasons for selecting that particular journal as the publication venue. Because interdisciplinary scholarship and teaching are often collaborative, the role and specific contributions of the individual in the research or team-taught course should be noted. Synthesis papers, often an important product of interdisciplinary scholars, should be clearly distinguished from reviews, as reviews may be discounted by evaluators as not being original contributions. Some interdisciplinary faculty members have complex career trajectories enabling them to bring a wealth of experience to their position. However, most positions outside the academy have lower (or no) expectations, or offer fewer opportunities, for publication. Since some reviewers focus on the number of publications after receiving the PhD as a measure of productivity, it may be useful to separate career experience into two or more categories so that the time periods when research and publication were possible are clear and that scholarly contributions other than peer-reviewed publications are also evident. The research, teaching, and service statement written by the candidate, and the chair’s letter, should also be written for a more general audience than may be the case for disciplinary scholars. The candidate’s statement is an opportunity to demonstrate an overarching plan or theme, including the candidate’s collaboration strategy. As noted earlier, teaching portfolios can be an effective way for interdisciplinary faculty to demonstrate the product of their teaching efforts to the public or to their disciplinary colleagues. Interdisciplinary student learning outcomes and assessment of student learning outcomes communicate to the students, internal colleagues, and external partners the value and purpose of the interdisciplinary teaching and learning program (e.g., Culligan and Peña-Mora, 2010). If the external reviewers are asked to address specific criteria, the CV and candidate statements should be structured so that information and explanations are easy to locate and understand. Evaluation Criteria Advancement of an individual faculty member should be dependent on demonstrating originality and independence of creative thought, having identifiable service contributions, multiple measures of teaching effectiveness, and collegiality. Typical questions asked during interim and tenure reviews are: • Does the candidate have scholarly quality of mind? • Has the candidate made an important intellectual contribution? If so, does the community recognize the candidate for it? • Is the candidate an effective teacher? • Is the candidate engaged in and contributing to the academic community? • Is the candidate on a trajectory indicating that (s)he will make significant contributions in the future? • Is it likely that the candidate will be able to support her/his research in the future through grant support? The evidence used to assess success differs from one discipline or department to another. However, some common factors do exist. These criteria typically include multiple measures of teaching effectiveness (including strong teaching evaluations), number of publications (e.g., peer-reviewed papers, book chapters, books, reports); the number of these on which the person is first author; the impact factor of the journals in which the papers are published; citations and awards received; the grants on which the person is a primary investigator or co-investigator; the relative prestige of the sources of funding; and the significance of the candidate’s service to the department/program, division, university, and profession. In interdisciplinary cases, faculty colleagues and administrators often raise an additional set of questions: • Why were the letter writers chosen from a different set of institutions than our usual set of peers? • Why are the letter writers unfamiliar with some aspects of the candidate’s scholarship? • What is the significance of this area of scholarship? • What is the standing of these journals? • What was the candidate’s contribution to multi-authored publications? • Why did the reviewers not know everyone on the comparison list? Why is the candidate not on the top of the comparison list? • Is the level of grant support and professional recognition consistent with other interdisciplinary scholars at a similar career stage? (Pfirman et al., 2005b) For example, interdisciplinary papers often focus less on innovation in disciplinary theory and methods and more on cross-disciplinary approaches and findings. The challenge is to be sure, in the review process, that evaluation of these very different types of publications is conducted according to appropriate criteria. Such criteria might include production of new interdisciplinary knowledge, development of new technologies or cross-disciplinary methods, or successful translation of technical or specialized knowledge for societal use. Disciplinary colleagues accustomed to higher productivity, citation rates, and journal standing may need an explanation of the time it takes to develop a contribution in a new field, and the difficulty of review and publication when research spans multiple disciplines. This is not to excuse sparse productivity or poor quality work, but rather to shift the emphasis of reviews towards intellectual achievement and leadership, rather than traditional metrics that may emphasize the number of publications. That said, indexes can be used in innovative ways to demonstrate interdisciplinary impact: as one example, reviewers can look at the number of subject categories (e.g. Porter et al., 2007) represented by journals with papers that cited the research. As the candidate moves forward in his/her career, up to and beyond tenure, similar evaluation criteria should ideally continue to be used in subsequent reviews.

Review Committees and External Reviewers There may be cases where it is desirable to keep the composition of the review teams, in terms of departments, disciplines, interdisciplinary fields, and even individuals, as similar as possible along the candidate’s career trajectory, in order to provide continuity in application of criteria. In most cases, it is best if the promotion and tenure process for tenure-track faculty involves review committees composed of faculty who have expertise in the faculty member’s fields and disciplines. Possibilities include: a joint committee from more than one department or a committee from one department with letters from the chair/director of others where the candidate has an affiliation. If the review will involve several departments, it is important to state from the outset what each unit’s decision-making role will be -- whether it will be independent and equal or whether one will have a subordinate, perhaps a consulting, role. Promotion and tenure committees should be made up, to the degree possible, of individuals in similar positions or with considerable experience in working with and reviewing people in similar roles. Where a sufficient pool of such individuals does not exist, the committee should include more than one person with a similar title and set of job responsibilities, even though the actual scholarly focus may be in an unrelated area as they will be familiar with the challenges of working in an interdisciplinary field. It is often also helpful to bring in an external reviewer (letter-writer) who is familiar with the state of the interdisciplinary field and the candidate’s scholarship at the time of tenure review. Outside reviewers are also increasingly used for interim reviews. It is often challenging to identify reviewers who have sufficient background to fairly assess contributions generated through interdisciplinary scholarship. In selecting external reviewers for emerging interdisciplinary fields, it is important to have both interdisciplinary scholars who work on closely related problems, as well as eminent disciplinary scholars who are aware of this area of research and are able to comment on its significance. The position announcement used when recruiting the interdisciplinary faculty member could also be included in the letter that goes out to external evaluators soliciting an evaluation. In addition, the external reviewers should be specifically asked to comment on interdisciplinary contributions and impact. This will serve as a reminder to reviewers of the differences and challenges of reviewing an interdisciplinary as compared to a disciplinary candidate. Because some interdisciplinary scholarship includes community and stakeholder interaction, reviews may also be solicited from individuals outside of the academy.

Readings Aboelela, S.W., E. Larson, S. Bakken, O. Carrasquillo, A. Formicola, S.A. Glied, J. Haas and K.M. Gebbie, 2007. Defining interdisciplinary research: Conclusions from a critical review of the literature. Health Services Research 42:1, Part I, 367 pp. http://www.blackwell- synergy.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00621.x. Boyer, E.L., 1990, Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Chamberlin, J., 2006. Uncommon ground: Interdisciplinary scholars share the benefits--and challenges--of teaching and conducting research alongside economists, historians and designers. APA Monitor on Psychology. 37(5): 26. http://www.apa.org/monitor/may06/uncommon.html. Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy (COSEPUP), 2004. Facilitating interdisciplinary research. http://www.nap.edu/openbook/0309094356/html/R1.html Creamer, E.G. and L.R. Lattuca, eds, 2005. Advancing faculty learning through interdisciplinary collaboration: New Directions for Teaching and Learning. J-B TL Single Issue Teaching and Learning. San Francisco, CA : Jossey-Bass. Choucri, N., O. de Weck and F. Moavenzadeh, 2006. Editorial: Promotion and tenure for interdisciplinary junior faculty. MIT Faculty Newsletter. Jan/Feb. 2006. http://web.mit.edu/fnl/volume/183/editorial.html. Culligan, P.J. and Peña-Mora, F., 2010. “Engineering.” IN: R. Frodeman, J.T. Klein and C. Mitcham (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity. New York, NY: Oxford Univ Press. DeZure, D., 2010. “Interdisciplinary pedagogies in higher education.” IN: R. Frodeman, J.T. Klein and C. Mitcham (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity. New York, NY: Oxford Univ Press. Eysenbach G., 2006. Citation advantage of Open Access articles. PLoS Biol 4(5): e157 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040157 Facilitating Interdisciplinary Research, 2004. Committee on Facilitating Interdisciplinary Research, National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, Institute of Medicine. The National Academies Press. Goldstein, D. S., 2006. Interdisciplinary inquiry: The aims of education. Syllabus for BIS 300F. University of Washington, 2006. http://faculty.washington.edu/davidgs/BIS300FSyl.html Holley, K. A., 2009. Interdisciplinary strategies as transformative change in higher education. Innovations in Higher Education 43(5): 331-344. Available at: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10755-009-9121-4 Klein. J. T., 2010. Creating interdisciplinary campus cultures: A model for strength and sustainability. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Klein, J. T., and Martin, P. J.S., 2012. Meeting institutional and administrative challenges of interdisciplinary teaching and learning. Conference on Interdisciplinary Teaching and Learning, Michigan State University. Available at: http://lbc.msu.edu/CITL/Klein-and-Martin-Invited- Paper.pdf NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, 2006. Interdisciplinary research. http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/interdisciplinary/. Nowacek, Rebecca S., 2009. Why is being interdisciplinary so very hard to do?: Thoughts on the perils and promise of interdisciplinary pedagogy. CCC 60(3): 493-515. Payton, A. and M.L. Zoback, 2007. Crossing boundaries, hitting barriers. Nature 445(22): 950. Pfirman, S.L., J.P. Collins, S. Lowes and A.F. Michaels, 2005a. Collaborative efforts: Promoting interdisciplinary scholars. Chronicle of Higher Education, 00095982, 2/11/2005, 51(23). Pfirman, S.L., J.P. Collins, S. Lowes and A.F. Michaels, 2005b. To thrive and prosper: Hiring, fostering and tenuring interdisciplinary scholars. Project Kaleidoscope Resource. http://www.pkal.org/documents/Pfirman_et-al_To-thrive-and-prosper.pdf Pfirman, S. and Martin, P.J.S., 2010. “Facilitating interdisciplinary scholars.” IN: R. Frodeman, J.T. Klein and C. Mitcham (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Porter, A.L., A.S. Cohen, J.D. Roessner, M. Perreault, 2007. Measuring researcher interdisciplinarity. Scientometrics, Vol. 72, No. 1 (2007) 117.147, DOI: 10.1007/s11192-007-1700-5 Preston, L., [2000]. Mentoring young faculty for success: Rewarding and encouraging involvement in cross-disciplinary research. ASEE Engineering Research Council Summit. available at

Appendix F: Suggestions for Advancing the Success of Interdisciplinary Senior Faculty NOTE: THESE SUGGESTIONS ARE DESIGNED TO COMPLEMENT EXISTING MIAMI UNIVERSITY POLICIES AND INFORMATION. NONE OF THE SUGGESTIONS IN THIS DOCUMENT SUPERSEDE UNIVERSITY POLICIES AND PROCEDURES. Introduction This document provides suggestions for senior faculty interested in pursuing interdisciplinary work and for administrators (department chairs, program directors, deans) working with senior faculty who are pursuing interdisciplinary teaching and research. It provides suggestions for better ensuring the professional success and retention of interdisciplinary faculty, including those who were originally hired to do interdisciplinary work as well as faculty who might have developed an interest in interdisciplinary work after being hired, tenured, or promoted. Since 1997, three ad hoc committees have been developed which offered specific and similar recommendations on advancing an interdisciplinary culture at Miami University: the 1997 “Ways to Encourage Interdisciplinary Teaching”; the 2006 “Report of the First in 2009 Coordinating Council Sub-Committee on Interdisciplinarity at Miami University”; and the 2011 Interdisciplinary Enhancement Committee Report. Each report identified the barriers to interdisciplinary work, the landscape of interdisciplinary activity at Miami at the time, perspectives from various stakeholders around campus, and key recommendations for how to enhance and encourage interdisciplinarity. The cornerstone of the 2006 report was a campus-wide survey that gathered data about barriers to interdisciplinary teaching and research. An open meeting for Miami faculty and administrators, which was held in November 2013 and sponsored by the Interdisciplinary Advisory Council, also yielded similar recommendations on fostering an interdisciplinary teaching and research environment at Miami. Findings from the November 2013 meeting and the previous committee reports as well as best practices gleaned from the professional literature have shaped the recommendations and ideas embedded in this document. Interdisciplinary Studies Today Colleges and universities are experiencing a marked increase in interdisciplinary research and education. As one researcher noted, for the past ten years, “interdisciplinary programs have multiplied at a dizzying pace” (Nowacek, 2009, 493), with “over half of current general education reforms includ[ing] interdisciplinary programs or courses” (494). Likewise, the National Academy of Science, the National Academy of Engineering, the National Science Foundation, and the Institute of Medicine have extolled the benefits of interdisciplinary research and taken steps to promote its expansion (National Academies Press, 2004; see also http://www.nsf.gov/od/oia/additional_resources/interdisciplinary_research/). Similarly, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Council of Learned Societies, and the Social Science Research Council have also recently developed and prioritized prominent interdisciplinary initiatives. Understanding the Benefits and Challenges of Interdisciplinary Faculty As summarized in the table below, faculty who engage actively in interdisciplinary teaching, scholarship, and service opportunities provide significant benefits and challenges for the University.

Benefits Challenges Teaching Focuses on exciting and cutting-edge subjects or topics Thematic focus can be appealing to students Team-teaching can promote faculty development, teaching excellence, and collaborations Often involves experiential learning (e.g., field experiences, service learning, collaborative learning) No or few textbooks Lack of sample syllabi or longstanding models to follow No clear body of knowledge to cover Team-teaching, due to its collaborative nature and the need for the instructors to learn new disciplines, can be more time-consuming Students and parents may not immediately perceive value Assessment methods may be unique Research Can be ground-breaking, pioneering Encourages a more holistic or comprehensive approach to learning Can appeal to major funding agencies Often involves collaborations across departments, divisions, or institutions Often involves social issues Lack of recognition by established scholars Lack of sustained funding opportunities Lack of familiarity with reputable journals and publication outlets Lack of peer reviewers and mentors Career trajectory less clear Extended start-up time Not as many honors as in disciplinary fields Can wrongly be considered less rigorous Requires time to cultivate and maintain Service Fosters community connections Builds bridges between disciplines, departments, divisions Enables faculty to become known on campus Multiple and competing demands Jointly appointed faculty serve two or more academic departments or programs; each department may not recognize the service demands required from the other Promotion Broadens network for reviewers and for the department and University Procedures & criteria may be biased toward disciplines Reviewers may assume disciplinary norms or standards

Robert Clark, Dean of the Pratt School of Engineering at Duke University, writes, It is clear that research and teaching “at the boundaries of traditional . . . disciplines [are] yielding tremendous gains. . . The simple act of brainstorming in a group of faculty having different backgrounds is tremendously exciting and stimulating. Such groups diminish the fear associated with suggesting ideas that are outside the accepted ‘dogma’ of a particular researcher’s discipline. There is less risk of being criticized by colleagues that understand when you approach the problem with a different background and perspective. As a result, this kind of brainstorming among colleagues from different disciplines can stimulate creativity, sometimes leading to radically unique ideas or approaches.”

Although supporting interdisciplinary research and teaching comes with challenges-- including ensuring administrative flexibility and support, seed funding, and constant exposure to faculty in other disciplines to expand the vocabulary, which can vary greatly from discipline to discipline—it is worth the effort. Understanding Senior Interdisciplinary Faculty Senior faculty who are involved in interdisciplinary teaching and scholarship may have followed one of four career paths: 1. They began their careers in more traditional single disciplinary roles and fulfilled the criteria for tenure by focusing on limited areas in considerable depth. Their interest in broadening out and linking with additional disciplines occurred well into a career, perhaps when the pressures of meeting tenure criteria have passed or years of experience have exposed the scholar to new insights and concepts that reinvigorate the original research/scholarship/creativity path. Such faculty may face the same difficulties experienced by younger scholars pursuing interdisciplinary activities. These difficulties can be addressed through improved assessment and reward policies for all faculty, regardless of rank.

2. Some senior faculty members have engaged in interdisciplinary activity throughout their academic careers. In this case, the issue is appropriate assessment during annual reviews and post-tenure review. Here too, assessment and reward policies that account for the special qualities of interdisciplinary activities can be applied. However, senior scholars may also experience the decline in research/scholarship performance that can be experienced in any field, and post-tenure reviews can be used to recommend actions to reinvigorate performance. Indeed, the cross-fertilization of ideas that is a feature of interdisciplinary work may help to resolve performance issues that arise when careers become stale and lose momentum with age.

3. Some senior interdisciplinary faculty may have worked for private or non-profit sectors and come to the academy at an advanced level but without the traditional portfolio of peer reviewed publications and teaching assignments. Strategies may be developed to identify, evaluate, and reward scholarly contributions other than peer-reviewed publications. Scholarly contributions might include, for example, significant interactions with regulatory agencies that have shaped public policy adoption and implementation, with substantial societal impact. Professional teaching development through CELTUA or other venues can be offered.

4. Some senior faculty members are well positioned to take leadership positions in interdisciplinary programs. This can be through the creation and implementation of interdisciplinary projects, centers, or institutes, or through mentorship of younger scholars. Strong leadership qualities are not the norm and should be nurtured when they arise, particularly for programs and projects focused on complex interdisciplinary problems and issues. Leadership training should be considered for those assuming leadership of large centers and institutes. The reviews of such administrators also need to be attuned to the atypical complexities of administering an interdisciplinary faculty, program, and infrastructure. Considerations for Senior Interdisciplinary Faculty The research, service, and teaching of senior interdisciplinary faculty members may have somewhat unique challenges and implications.

Considerations Related to Interdisciplinary Research Associate or full professors involved in interdisciplinary scholarship may approach their research in different ways, and each approach has somewhat different implications. They can work on interdisciplinary questions individually, bringing together information from different fields, or they can work in teams. Their projects frequently cross departments, and often involve applied problems with unusual stakeholders, outside of the academy. Interdisciplinary work comes in a variety of forms (Rhoten and Pfirman, 2007): (5) Cross-fertilization –adapting and using ideas, approaches and information from different fields and/or disciplines. (6) Team-collaboration—collaborating in teams or networks that span different fields and/or disciplines. (7) Field-creation--creating new spheres of inquiry that sit at the intersection or edges of multiple fields and/or disciplines. (8) Problem-orientation—addressing problems that engage multiple stakeholders and missions outside of academe, for example that serve society. Collaborative interdisciplinary research can sometimes involve higher networking costs. Colleagues often have different priorities, and it takes time to learn how to cross disciplinary language barriers. Time and energy are also required for identifying potential partners, maintaining contact with them, and writing and then revising multi-authored documents. If the collaborators are not at the same institution, support for travel can be vital. Seeing collaborators at meetings and/or visiting them in their home institutions are excellent ways to maintain connections and build recognition. Travel support for interdisciplinary scholars to attend meetings of a number of disciplinary groups is also helpful. As collaborative interdisciplinary projects evolve, faculty need to make clear their unique contributions. Interdisciplinary research projects frequently take a long time to produce results, in part because of the networking required to bridge cultures and communities, but also because finding funding for interdisciplinary research can sometimes be a challenge. While there has been increasing attention to interdisciplinarity in recent years, requests for proposals for interdisciplinary research and scholarship may not be as predictable as RFP’s in the traditional disciplines. Interdisciplinary research, particularly research that cuts across widely divergent disciplines and fields, can be difficult to publish in recognized journals. There are fewer journals that specialize in broadly interdisciplinary research and among the ones that do, the impact factor varies greatly. While interdisciplinary research is often published in conference proceedings or as book chapters, because these are not usually indexed in traditional ways, they are more difficult for other scholars to find, and therefore cite.

Considerations Related to Interdisciplinary Teaching Interdisciplinary teaching entails the use and integration of methods, concepts, and analytical frameworks from more than one academic discipline to examine a theme, issue, question or topic. The hallmark of interdisciplinary education is integration of knowledge and guiding principles from multiple disciplines to systematically form a more complete, and hopefully coherent, understanding of the issue under examination. Interdisciplinary teaching activities may need additional support and development, particularly when the faculty member is involved in developing new courses that span multiple disciplines—often without a standard textbook or readily available teaching resources—or when the faculty member is piloting new experimental teaching approaches. Although there is no single preferred pedagogy or teaching approach for interdisciplinary courses, most interdisciplinary faculty are operating fields of knowledge that may be new to them and advancing active forms of learning such as service learning, team-teaching, inquiry-based education, learning communities, or collaborative learning, all of which may take experience and professional development to master. Because of the unique nature of interdisciplinary teaching, teaching portfolios can be a dynamic and performance-based way for interdisciplinary faculty to demonstrate the product of their teaching efforts (e.g., Goldstein, 2006; DeZure, 2010) to their colleagues. Moreover, because the learning outcomes for interdisciplinary courses can differ from those advanced in disciplinary learning contexts, assessment measures may be unique and require significant time to develop. The Center for the Enhancement of Learning, Teaching, and University Assessment can provide assistance on developing teaching portfolios. For more information on interdisciplinary teaching and assessment, see: http://miamioh.edu/oue/interdisciplinary/index.html.

Considerations Related to Service of Interdisciplinary Faculty Interdisciplinary faculty members may have a joint academic appointment, serve as an affiliate in a program or department, or be heavily involved in a center, institute, or major interdisciplinary initiative outside of their home department. As a result, the nature and extent of service (to the department, program, division, University, profession, community) may be more expansive than the service record of a faculty member who works within the confines of a single discipline or department. It is important to remember that because interdisciplinary programs, centers, and institutes have few (if any) core faculty assigned to them, they largely rely on the contributions of faculty whose lines exist in other departments or divisions. Consequently, the service the faculty members offer these units may at times be substantial.