ADMINISTRATIVE PROCESS SPRING 2006 Julien Morissette

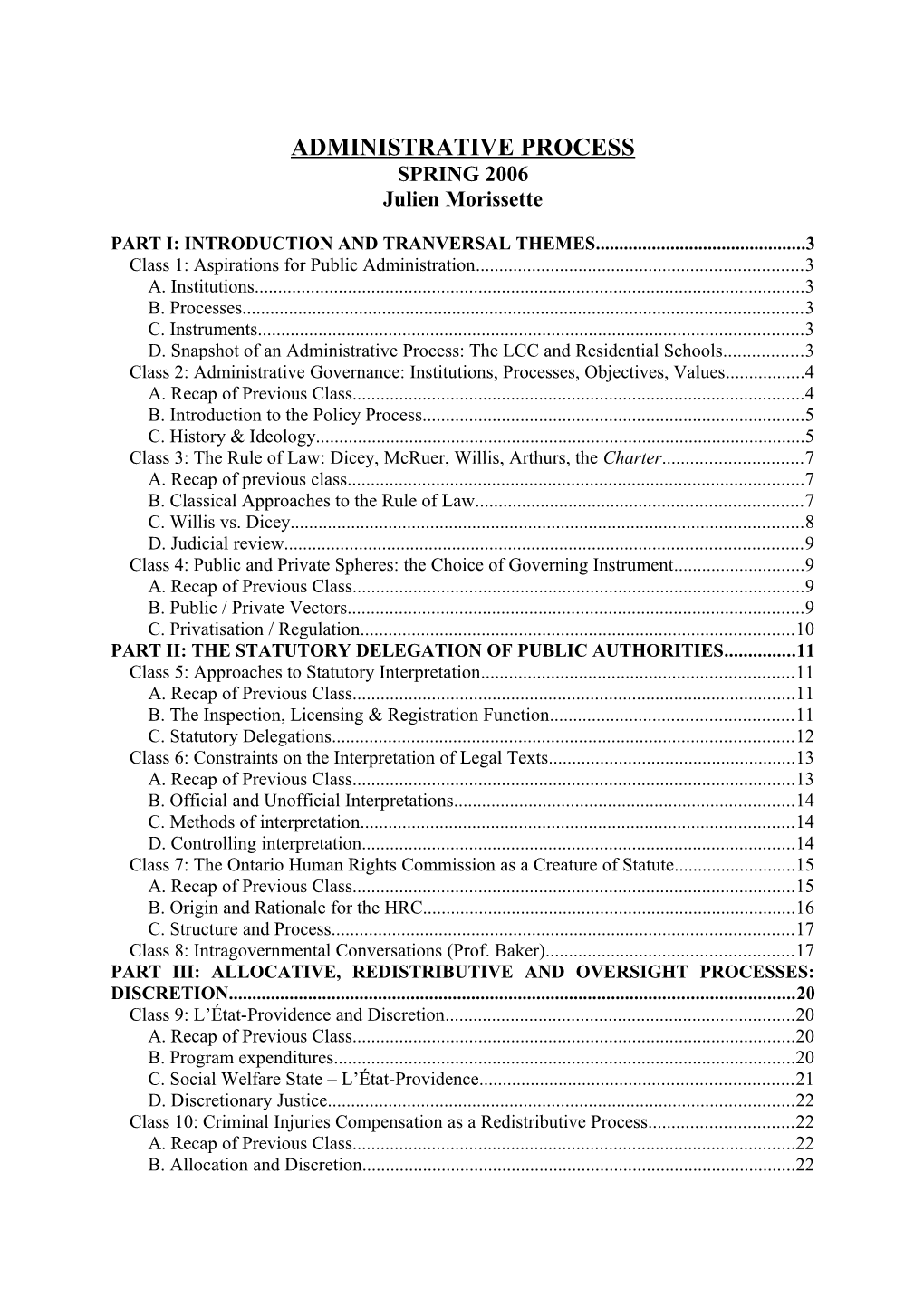

PART I: INTRODUCTION AND TRANVERSAL THEMES...... 3 Class 1: Aspirations for Public Administration...... 3 A. Institutions...... 3 B. Processes...... 3 C. Instruments...... 3 D. Snapshot of an Administrative Process: The LCC and Residential Schools...... 3 Class 2: Administrative Governance: Institutions, Processes, Objectives, Values...... 4 A. Recap of Previous Class...... 4 B. Introduction to the Policy Process...... 5 C. History & Ideology...... 5 Class 3: The Rule of Law: Dicey, McRuer, Willis, Arthurs, the Charter...... 7 A. Recap of previous class...... 7 B. Classical Approaches to the Rule of Law...... 7 C. Willis vs. Dicey...... 8 D. Judicial review...... 9 Class 4: Public and Private Spheres: the Choice of Governing Instrument...... 9 A. Recap of Previous Class...... 9 B. Public / Private Vectors...... 9 C. Privatisation / Regulation...... 10 PART II: THE STATUTORY DELEGATION OF PUBLIC AUTHORITIES...... 11 Class 5: Approaches to Statutory Interpretation...... 11 A. Recap of Previous Class...... 11 B. The Inspection, Licensing & Registration Function...... 11 C. Statutory Delegations...... 12 Class 6: Constraints on the Interpretation of Legal Texts...... 13 A. Recap of Previous Class...... 13 B. Official and Unofficial Interpretations...... 14 C. Methods of interpretation...... 14 D. Controlling interpretation...... 14 Class 7: The Ontario Human Rights Commission as a Creature of Statute...... 15 A. Recap of Previous Class...... 15 B. Origin and Rationale for the HRC...... 16 C. Structure and Process...... 17 Class 8: Intragovernmental Conversations (Prof. Baker)...... 17 PART III: ALLOCATIVE, REDISTRIBUTIVE AND OVERSIGHT PROCESSES: DISCRETION...... 20 Class 9: L’État-Providence and Discretion...... 20 A. Recap of Previous Class...... 20 B. Program expenditures...... 20 C. Social Welfare State – L’État-Providence...... 21 D. Discretionary Justice...... 22 Class 10: Criminal Injuries Compensation as a Redistributive Process...... 22 A. Recap of Previous Class...... 22 B. Allocation and Discretion...... 22 2

C. Victim Services and Moral Hazard...... 23 D. Problem: Saskatchewan Victims of Crime Act...... 23 Class 11: The Public Protector: Formal and Informal Accountability...... 24 A. Recap of Previous Class...... 24 B. Why an Ombudsman?...... 25 C. Character of the Institution...... 25 D. Outcomes, Process, Qualities...... 25 E. List of Alternatives...... 26 F. Maladministration...... 26 PART IV: ALLOCATIVE, REDISTRIBUTIVE AND OVERSIGHT PROCESSES: DISCRETION...... 26 Class 12: Statutory Instruments and Regulation: Ex ante Oversight...... 26 A. Recap of Previous Class...... 26 B. Nature of Normativity...... 27 C. Kinds of Legislation...... 28 D. Why Delegated Legislation?...... 28 D. Statutory Instruments & Regulations...... 28 Class 13: Ex post Review of Micro-legislation...... 29 A. Recap of Previous Class...... 29 B. Ex Ante Controls...... 29 C. Ex Post Controls...... 30 D. Exercise on Regulation-Making Powers...... 30 Class 14: The CRTC as a Policy Hybrid...... 31 A. Recap of Previous Class...... 31 B. Theories of Regulation...... 31 Class 15: The CRTC as Government in Miniature...... 32 A. Recap of Previous Class...... 32 B. Policy Process of the CRTC...... 33 C. Independence & Accountability...... 33 PART V: GOVERNMENTAL ENTERPRISES: PRIVATIZATION, PARTNERSHIPS, OUTSOURCING...... 34 Class 16: Crown Corporations: The Mission and Mandate of the CBC...... 34 A. Recap of Previous Class...... 34 B. Historical Contingency...... 34 C. Owning and Operating...... 35 D. Purposes and Justifications for Crown Corporations...... 35 Class 17: The Rise and Fall of Petro-Canada...... 36 A. Recap of Previous Class...... 36 B. Why Public Ownership?...... 36 C. Why Privatise?...... 37 Class 18: Public-Private Partnerships; Voluntary Associations...... 38 A. Recap of Previous Class...... 38 B. Public-Private Vectors...... 39 C. Why the State?...... 39 PART VI: CONCLUSION AND GENERAL REVIEW...... 40 Class 19: Aspirations for Public Administration Revisited...... 40 A. Recap of Previous Class...... 40 B. Synopsis of the Class...... 40 C. Case Study: Recreational Drugs...... 41 D. Conclusion...... 42 3 4

May 8th, 2006

PART I: INTRODUCTION AND TRANVERSAL THEMES

Class 1: Aspirations for Public Administration

Law is the endeavour of symbolizing human conduct governed by rules. Administrative law is about institutions, instruments, processes and values through which public policy is translated into law.

Child in the well story… Insurance companies and governments function much on the same way, the idea is to make informed choices – based on the big picture, not just individual problems. Schipol fly in the urinal story… Sometimes, commanding or ‘bribing’ is not necessary to achieve the desired behaviour.

A. Institutions

State Non-State International Parliament, courts, Crown universities (close to the UN, WTO, NATO, NAFTA corporations, departments, State, also RMC), religious arbitrators, ICC, MSF, ILO, PMO-PCO, police, tribunals, institutions, charitable orga- Mercosur, IBRD, ADB, statutory agencies (munici- nisations, private corpora- Catholic church, Al-Qaida palities, health boards, tions, unions, partnerships, airport corporations), GG, local NGOs or quasi-NGOs army, Indian Act bands dependent on the State (quangos), political parties, clubs, family

B. Processes

We will exclude some things, such as terror. A non-exhaustive list: voting, consultation, lobbying, adjudication, negotiation, contract, arbitration / mediation, markets, conflict, revelation / education / indoctrination, money, bequeathing, command / orders, deliberate resort to chance, practice / custom.

C. Instruments

Making rules, taxing, subsidizing… These may also be looked at as processes or even institutions. The three above categories are simply different angles to look at the institution of government.

D. Snapshot of an Administrative Process: The LCC and Residential Schools

Issue (2a): How to deal with claims of residential school victims without being bankrupted by lawsuits? What kind of answer should be given? Former public policy (2d): Assimilation (hindsight), education, economies of scale (residential) for education, understanding of dominant culture, little supervision, many unqualified / authoritarian / predatory teachers, evangelization, etc. Those looking for the story told in a certain way: department of justice, churches, aboriginal leadership. 5

What you get from a civil trial: money, publicity, perhaps a moral judgement.

To define the system, the LCC has to tentatively figure out its objectives. It needs to find the facts (objectives are defined by these and colour them in a certain way) through evidence (documentary sources, personal accounts) found by independent or in-house researchers, polls, self-reporting, public inquiries, police / CSIS investigations, parliamentary committees, NGOs. On this long list, the government picked the LCC. Why? Get it out of the Department of Justice, which both heightened the profile and provided independence. There was also a wish for a legal response.

Once the LCC has the mandate, what do you do? Many options were explored: ex gratia payments, ombudsman, injury compensation board, TRC… The three retained options were TRC, redress programs, community-based initiatives (the abused tend to become abusers). Compensation to individual survivors was ranked second-last on the ‘hope’ list compiled by the LCC. If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail, if all you have is torts, everything looks like a tort claim. On top of the list was public acknowledgement, followed by apology, wrongdoers taking responsibility, help / counselling to move on. Ranking of those things that cost money: prevention, healing communities, public memorial, individual compensation.

Not everyone was happy with the report. Outside government and aboriginal lawyers, other abuse survivors, some lawyers, churches were at least somewhat unhappy. The most opposed group was the teacher’s union, it sued the LCC. There was a perception that every single residential school teacher was an abuser.

May 9th, 2006

Class 2: Administrative Governance: Institutions, Processes, Objectives, Values

A. Recap of Previous Class

The theme of this class is diversity, multiplicity or goals, tools, processes, actors, instruments. Public policy is a never-ending adjustment to circumstance. There is no such thing as ‘getting it right’, the most one can hope for is working to policy instruments that reduce the distance between efficacy and effectivity, basically desired effects without side effects. The cure should be better than the illness. Most of what an LRC and an LCC do is find solutions to problems coming from yesterday’s solutions (cf. Lord Mansfield on the CL).

The terrain on which one operates changes constantly. Ex.: When medicare was set up in the 1960’s, the assumption was that 60-65% of the cost would be spent on doctors and nurses in medical practice. By 1985, 80% of expenditures where elsewhere: hospitals, testing procedures, drugs. In 2005, only about 15% is spent on doctors and 30% on drugs. This means the institutions may have to be rethought. Another ex.: Sometimes a policy instrument is created for a purpose and one discovers it works very well for something else that was unforeseen. The classic ex. in Canada is the ‘baby-bonus’ or family allowances established in 1947. The initial reason was to encourage consumption, with increased production and more jobs for 400,000 demobilized soldiers (not so much to ensure that children were not in poverty, or to help the mother to whom the cheque was made out, or to encourage natality). The government also created the CMHC to make housing more accessible and increase 6 purchases at the same time. The baby bonus was similar Keynesian economics, just like guaranteed mortgages. By the 1960’s, the baby bonus became a part of the welfare State, as education, medicare, CPP... Arguments against the claw-back in the 1980’s were in terms of family policy.

Administrative law is the translation of public policy in processes and institutions to achieve outcomes. One challenge is that we often lose sight of what we are trying to do. Three sub-points on this question: - Administrative law is about the management of public goods in a manner that… o Promotes and reinforces society’s values. o Enhances human agency / freedom. o Achieves efficiency. Much of the policy debate is to balance these three goals. Many people in Canada think that equality is a value of society. We know however that the quest for equality translates into a diminution of agency. See the challenges to HRCs. - Allocation of benefit and burden. o Legitimacy (formal, tradition--charisma--legal-rational à la Weber, the foundation of political authority is outside law in a narrow sense, the question is what is the formal source of authority / substantive, such as expertise, age, experience, fulfils a need, experimentation, flexibility). o Procedurally fair. o Substantially just. - Is the benefit from structuring activity higher than costs of restricting freedom? In a liberal democracy, the presumption is that action is permitted, subject to some constraints. But the deep paradox of freedom is that if we were totally free, we could not do anything (say we decide that any word means anything…).

The “We” in “We the people” represented men who owned land, i.e. 4-5% of the population. Does that mean that the American State and its institutions illegitimate? There are many presuppositions about human beings, behaviour, etc., “otherwise you’d just have a big army”.

B. Introduction to the Policy Process

How should States go through the business of implementing public policy? See Peters’ and Icilis’ articles. There is normally a presenting issue (ex. factories closing down), few public policies appear ex nihilo. In the case of residential schools, the issue was litigation and potential huge liability. Once this appears, one must look at the policy problem (ex. lack of competitiveness) of which this issue is an instantiation. One must then look at background considerations (ex. higher labour costs, payroll taxes, little R&D). Then comes the range of options (ex. FTA, manufacture sales tax was replaced with the GST [net effect estimated to be 200,000 jobs], UI became EI to subsidize seasonal employment, retraining and parental leave) and weighing advantages and disadvantages of each. Finally, there is a balancing of redress for the past (in the US, 80% of farm subsidies go to 5 companies!) and re- imagining the future.

C. History & Ideology

Much of what we are doing assumes that we are in Canada, in 2006. Peters outlines the importance of ideology for guiding public policy. From the 1950’s onwards, political theorists puzzled to the existence of red Tories in Canada, with no parallel in the US. Another ex. is the 7 significant presence of labour / socialist movements in Canada since at least the 1920’s with few significant parallels in the US.

Using a simplified political diagram to represent Canada…

neo-con. Hierarchy facist whig tory

Individuals Organic

liberal socialist libertarian Egalitarianism communist

Historically, each cell has been represented and still is. Whereas in the US, the right side of the diagram is almost completely absent. One of the classic explanations is the “fragment theory” of Louis Hartz. He hypothesized that the moment a new State is founded and there is a break from the colonial power will give a clue on the dominant ideology. The US revolution was against toryism. Tories were exported to Canada in what is now Ontario, aided and abetted by the ultramontane structure in Quebec. In the 19th C., the US debate was whig (Hamilton) / liberal (Jefferson), in Canada it was tory (MacDonald) / liberal (MacKenzie). Political ideologies often spawn their opposite, toryism spawned socialism in Canada. Red tories are generally tories but who see government as a positive actor in the economy (conservatives created most Crown corporations).

Childcare for: - Tories => State franchising, institutions such as private schools. - Socialists => Public institution such as public schools. - Liberals => Private daycares, with a tax credit. - Whig => Private daycares, ‘means tested’, with vouchers for low incomes.

How has the presence of tories and socialists in Canada influenced public policy? This takes us into history. Policy analysts say that Canada has lived through two national policy cycles and is embarking on a third: - Post-1870 depression MacDonaldian NP with infrastructure building, immigration and high tariffs [a revisionist theory said Canada was built as a hinterland for the Montreal commercial elite], all Canadian liberals were opposed. This was the exoskeleton of Canada. Aligned with this was creation of Crown corporations, with a load of political clientelism (CP rail, Bell Canada were created by friends of the Conservatives…). - Post-1929 realisation that charities could only do so much, the Rowell Sirois report of the late 1930’s was the blueprint for the welfare State, creation of Crown corporations, etc. The instruments changed: regulatory State, agencies, bureaucracies, tax & spend. Attempts to use the first NP (Petro-Canada) turned out to be a dead end. This was the ‘lifeblood’ of Canada. - Post-1978-82 (second oil shock), a new cycle seems to have started. The instruments are clear, but the goals and values much less so. Instruments: Charter, FTA, NAFTA, GST, de-regulation, privatisation, Meech Lake, balanced budget… What conception of society do these instruments reflect? Politically liberal, State as business corporation, (sub- and exo-)urbanisation. 8

Just because one is a whig or a liberal, even if government has a role in some field, ideology will shape policy instruments: childcare or early childhood education?

May 10th, 2006

Class 3: The Rule of Law: Dicey, McRuer, Willis, Arthurs, the Charter

A. Recap of previous class

How can the GST, NAFTA or the Charter be governing instruments? Taxation (mostly its design) can be a response to a problem, just like creation of an agency to control employment. The assumption of the Charter is to offload significant political decisions onto the courts, which will create standards that will become applicable across the regime.

This touches upon the practice of law, even if this is usually associated with civil servants or policy analysts: creating systems of rules in M&E, tax planning, etc. Law can be practiced proactively through instrument design.

B. Classical Approaches to the Rule of Law

Reading texts from the early 20th C., such as Dicey’s, requires contexts. Asking the standard questions:

- Who and when? Alfred Dicey was a constitutional law professor / scholar at Oxford and part of the landed gentry. Under assault at that time is his ‘cosmology’, the welfare State is being created. In 1881, non-land owners got the right to vote. The primary resistance was the House of Lords, which lost its veto capacity in 1911. The next ‘bet’ was the courts. The articulation of the constitutional doctrine was embedded in the politics of the time. Dicey claims history as a basis “since the Norman Conquest” without justification.

- Where? The UK. These theories did not emerge in the US (“We the People”, not “Me the King”) or France (natural law, the French revolution grounded sovereignty in the ‘bottom’), although these countries had their own rule of law theories.

- What? First, ordinary law (statutes, common law) applied by ordinary courts. Extraordinary law are discretionary powers, regulations / delegated legislation. Extraordinary courts are tribunals (vs. KB, Chancery, Admiralty, Probate, Ecclesiastical… which were merged in the 19th C. but were a ‘foundational principle’). Second, no one is above the law (unlike French droit administratif [supremacy of public law] which, purportedly does not exist in the UK, no distinction between public and private law, no specific law that applies to public officials, Dicey later recanted on this distinction). Third, citizens are protected by the discovery remedies (mandamus, quo warranto, certiorari… see the Magna Carta which says “if X happen you can do Y”) as opposed to abstract propositions in constitutional documents (France and the US at the time, now Canada). All three of these were wrong in their particulars but right in their general principles.

- Why? Urbanization, wage labour, rise of unions, workers compensation, consumption goods, rental of housing, automobiles. For every one of these perceived changes there 9

was a remedy: zoning, rent control, consumer protection, workers’ compensation, permission of unions, regulation of highway traffic, etc. Three private law principles were attacked: o Freedom of contract. o Fault-based liability. o Private property. Legislative jurisdiction was being ‘chewed up’. This gives a completely different face to the idea of rule of law than the way this idea is understood today (connected to a conservative political agenda? seen as inherent to democratic legal order).

In Dicey’s cosmology, the problem was too much government, delegated legislation, discretion to unelected official, power to non-judicial decision-makers, social engineering.

C. Willis vs. Dicey

There were three moments in the 20th C. when Dicey’s concerns came to the fore: original exposition, 1930’s when the British Parliament was trying to deal with the depression (Lord Hewart and Laski!), 1960’s (McRuer, judge, Willis, professor at U of T and Dalhousie). In 1962, a police investigation in Ontario on some criminal activity determined there was organized crime in Ontario, the AG of the time, Fred Cass (Leslie Frost government), decided to propose amendments to the police act: suspected members of the mafia could be held incommunicado once arrested for 48 hours. There was a huge debate so Leslie Frost ask McRuer CJO to run a commission of inquiry. There was a five volume report after 5-6 years (1968-70), which strongly echoed Dicey. This was the centre of much activity to ‘rein in government’.

What are the principle concerns Willis has What would have McRuer answered? with McRuer? Rights-based approach is biased. Legal questions, for which judges and lawyers are most qualified. Lawyers’ and judges’ perspective (not civil Rights-based approach upholds individual servants’). rights. Out of touch with the present. In touch with principles / values if not facts (not good just because it is). Ideological approach. The question is not empirical. Unitary, one-size fits all approach. One law for all citizens.

In five volumes, there not a single case study! There are a lot of theoretical concerns about the bad things civil servants could do, but no real examples. The McRuer Report is a case of idealized version of courts, worst practical view of government. Practice always looks bad when compared with theory…

It’s hard to compare the well-paid, high educated status of a judge with the lowest paid, scantily educated clerk at some border crossing. One would expect judges to perform better. How can the administrative State be improved? Training and education is fundamental. Increasing pay and job satisfaction attracts more qualified candidates. Procedural safeguards can become unmanageable (mass adjudication… 24,000 trucks crossing the Ambassador Bridge every day, 500,000 lanlord-tenant decisions in Ontario yearly). Twenty to one, the biggest complaint against public administration is “pig headed civil servants who won’t bend the rules” – not enough discretion instead of too much! 10

Why does Parliament enact privative clauses? Concerns about expertise, costs, avoidance, biases of judges, etc. are sometime legitimate. A lot of bodies are created to push a certain policy agenda. “Law is just politics by another name, two forms of politics being balanced: rule of law and agenda of the day”. We live in a political democracy, not a judocracy.

D. Judicial review

The Constitution is a basis for challenges (mostly separation of powers and Charter). If the statute passes, the next thing down is challenging the decision on the basis of due process (bias, natural justice, reasons), jurisdiction (if power to do X, say that the body did Y; this turns out to be trickier than it seems), abuse of discretion (irrelevant considerations, improper purpose, Duplessis told Archambault to yank the permit, sub-delegation, didn’t look at case’s merits but applied policy). This is almost a right of appeal.

The ordinary control of administrative action works very much like s. 7 of the Charter. But there is no s. 33 in administrative law unless it is directly invoked by Parliament. Today, the Diceyan rule of law has transmogrified into control of exercise of discretion and jurisdiction. In the final instance, there is no immunity to judicial review.

May 11th, 2006

Class 4: Public and Private Spheres: the Choice of Governing Instrument

A. Recap of Previous Class

Three main ideas were covered. First, many considerations get reduced to single dichotomies, but apparently simple distinctions (pro- or anti-judicial review) actually cover a lot of ground. Second, the way the “rule of law” idea was employed was driven by history and social circumstances. Today, international entrepreneurs are the major proponents of the “rule of law”… Third, the idea that the world divides into law, constrained authority, rational justification vs. politics, unconstrained authority, consequentialist reasoning is unfounded.

CL grants no right of appeal from tribunals. However, superior courts define the border of their jurisdiction under statute and the Constitution. This is the basis of judicial review. Privative clauses attempt to limit courts’ ability to judge borderline issues. Remember that there is no such thing as an ironclad privative clause. Decisions like Crevier have held that judicial review is constitutionally guaranteed. Obviously, there is a problem of conflict of interest for superior courts.

B. Public / Private Vectors

What is public, what is private? What is public law, what is private law?

Private law Public law Public social activity Private social activity Tort, Contract, Property, Criminal, Constitutional, army, police, transportation, family, private property, Wills & Estates, Family, Maritime, Public natural resources, religion, personal Equity & Trusts, Secured International, communications, streets, associations, business, Transactions, Private Environmental, Aboriginal, weather, public health, home, sexuality, “other International Law, Space, International elections for political office, social norms” 11

Remedies, Restitution, Sale, Development, Tax, social norms, international Real Estate Transactions Administrative, Securities organizations, social Regulation, Labour welfare, basic education

At different times and in different societies categories migrate and fields of law migrate. There are also many borderline cases: public torts, zoning, expropriation, chartered corporations… There are many migratory phenomenons. Public => private : governments should act as corporations to become more efficient, tradeable emission permits, four times as many security guards as there are peace officers, ‘streets’ in shopping malls, ‘private’ parks (McGill!), gated communities, private industrial parks, voucher education and healthcare, private tolled highways, private sewer and water companies… Private => public: corporations should act as governments to become more accountable, contracting out of government services, non-smoking by-laws in restaurants, domestic abuse, child abuse and welfare, workplace discrimination legislation, former torts handled by public law regimes (labour, automobiles…), politicized religious fundamentalism…

Hayek’s cosmology Private Public Non-State State Individual Collective Freedom, Autonomy, Rights Interests Market Politics Courts (adjudication) Courts (“any reasonable factors”) Corrective or commutative justice Distributive or allocative justice

In corrective justice, the status and relative economic entitlement of the parties is irrelevant, only the nature of the transaction is important. Our first inclination is to think that private law is adjudication done by courts, public law administrative law done by government. What about the Régie du logement or Small Claims Court which are administrative bodies doing adjudication? Or courts making a decision based on “just circumstances” (ex. alimony) or allocating public resources (CRTC could do auctions for frequencies)?

Frequently, public goods have to be allocated. One needs a good to distribute, a class of beneficiaries and some criterion for allocation for distributive justice. This is completely different from corrective justice. Yet punitive, moral or treble damages in torts have a strong redistributive component. Restorative justice is also an interesting case between corrective and allocative justice (unjust in Aristotle’s framework, as there were only ‘2 kinds’ of justice).

C. Privatisation / Regulation

When we start looking at case studies, we will see that private / public activity or law are not the only distinctions. But many debates in agencies have to do with mix and match between allocative and distributive justice. As a government, how does one know which one to pick? The only answer is that a team should be built to be greater than the sum of its parts. Every action also has collateral effects, which must be considered. Public policy is more than interest groups fighting in parliaments to carve up the body politic. Sometimes privatizing works for the public good. These phenomena have to be studied in details, beyond ideology.

May 15th, 2006 12

PART II: THE STATUTORY DELEGATION OF PUBLIC AUTHORITIES

Class 5: Approaches to Statutory Interpretation

A. Recap of Previous Class

First, what we normally think of as private and public law does not necessarily track what we imagine to be private and public space. It flows from that a number of things associates with private law (contracts, torts, property…) are in fact regulatory positions. Certain types of conduct shall not be subject to supervening government regulation. For ex., only certain types of harm lead to extra-contractual liability: regulatory position that only certain types of wrongs deserve compensation. Same thing for contracts: not every agreement is enforceable. In private law, there is in fact much regulation: recognizing something as property or not, imposing good faith in contract, public order, etc. The Legislature has the same choices to make when it decides to have a Chief Apiarist or to enable the sale of genetic material. “Even the absence of law is law whenever Parliament is enabled to act. The quantity of regulation is a constant, the only thing that changes is who, what, when, how?” - Macdonald.

In 1968, Parliament took away the offence of buggery for consenting acts between adults in private, by amending the Criminal Code. This was a regulatory choice, the State ‘moved out’. There is a different between this type of choice and recognizing same-sex marriage. This is a public act, it is not a private one: deregulation in the private sphere, regulation in the public sphere. Sorting is difficult… There is a huge range of possibilities for a State that wants to do something.

B. The Inspection, Licensing & Registration Function

The Apiary Inspection Act (NB) is both short and simple. It also is in the category most common for statutes: inspection, licensing and registration.

Every province had such an act at one time, today all provinces do except Alberta and Ontario (repealed in the late 1990’s). In these two provinces, there are officials in the Ministry of Agriculture in charge of the file. They receive their powers from the Ministry of Agriculture Act. The lack of a specific statute does not mean there is no governmental presence.

There is no preamble to the statute, it doesn’t say what its purpose is. Possible purposes: - Standardization of industry practice. - Controlling apiary diseases. - Health and quality control. There is no attempt to protect public health or control market entry / quantities in this statute.

It doesn’t appear any voter lobbied for this. Honey producers, hive and queen traders, basically the bee-keeping industry were behind this act. They are a powerful lobby: every US state has a similar structure.

Reasons behind this… 13

Reason Truth Advertisement Public trust X Protecting one’s bees X X Protect the bee market X Shift cost on government X Limited expertise X

What other regulatory strategies are open to address bee “health” concerns? The authority could be delegated to a trade association (self-regulation, such as law societies). Markets can discipline, for the future through publicity and for the past through contract or tort (causation problem – could use market share liability, tantamount to insurance or loss-spreading here). There could be an insurance scheme. Or outsourcing to a private company as opposed to self- regulation (in some sense, mandatory insurance does that). Another option is nationalizing the industry (ex. northern cod). The last option is criminal law (certainty of detection is a deterrent, unlike the potential sanction).

C. Statutory Delegations

A statute is an instrument by which public authority can be delegated to a person. This ‘person’ may be a private person, a specific official, an employee of a Department, a self- regulating association, a company… It was only starting in the 17th C. that the Crown’s power to delegate came to be regulated by statute rather than a part of the royal prerogative. Many things that ministers do are not directly given by statutes. For ex., few statutes say that the Minister of Finance has the power to prepare the budget. In this course, we will look almost exclusively at statutory authority (including delegated legislation).

What does a statute do? One should not be deceived by the title, Red Tape Reduction Act…

How (generic register)? The AIA is an inspection, licensing & registration statute, not criminal law or setting up some agency. The AIA provides for a regime of inspection, a registration scheme, establishes a hierarchy of authority, creates prohibitions, gives a power to quarantine and destroy property, labels actors, outlines powers and duties, creates fines and penalties, operates a publicity regime (sign). The most significant ones are underlined.

Who? Hammer Nail Minister (s. 1,2) Bee-keepers (s. 1, 3) Provincial Apiarist (s. 2) Other people (s. 5, 10) Lieutenant-Governor in Council (s. 14) Queen bee-keepers (s. 11) Crown in right of NB (s. 13.1) Sprayers of blooming trees (s. 12) Judge (s. 7) Renters for pollination (s. 14(c)) Court of competent jurisdiction (s. 8.3) Importer (regulation) Implied: police, bailiff, prosecutor

Who runs the operation? The office of the Provincial Apiarist. He is responsible to the Minister, who appoints the Provincial Apiarist and the inspectors. He may fire inspectors upon recommendation of the Provincial Apiarist (at pleasure appointment, can’t be sued for dismissing). 14

Who has the powers? We’ll divide powers in two. First, management powers (Minister, Lieutenant Governor in Council and PA). Even a simple statute like this contains management powers. Often, most of a statute is a list of management powers… Second, powers vis-à-vis bees. The inspector has power of quarantine, seizure, destruction (s. 8) and also to inspect (s. 6). The PA can quarantine imports (s. 4). The inspector recommends moving bees to portable frames, but the PA decides (s. 9). The PA compels an annual report (s. 3(2)).

What are the processes? Inspection is the main one. But there is also a process of publicity, process of signage (s. 3.1), certification to import bees (regulation), registration of bee- keepers, filing of a return. There are many self-reporting processes.

What are the prohibitions? Can’t spray arsenic on fruit blossom, can’t ship candy if the honey hasn’t been boiled for less than 30 minutes, can’t ship an infected queen, can’t sell or transfer infected bees, can’t possess infected equipment. These are regulatory offences, not crimes (see 91(27) CA 1867). Several offences are absolute liability (confused case law on provincial offences). The punishments are stated in a list, which refers to the Provincial Offences Procedure Act. For ex., breaching s. 4 (category F offence) involves a fine of $240- $5120 or a maximum of $7620 for repeat offenders (s. 56-57). S. 58 says that offences committed for personal gain or to avoid regulation, the judge may impose the fine s/he deems fit. This is a standard feature of regulatory offences. It is the provincial court, criminal division that deals with these offences (“assembly-line justice”). There are very few prosecutions under these statutes, only scofflaws usually (other compliance attempts made first).

May 16th, 2006

Class 6: Constraints on the Interpretation of Legal Texts

A. Recap of Previous Class

As we look at the AIA, our assumption is that the delegate is a government official or another person given the role. But a number of provincial statutes appoint judges as administrative officials (persona designata). A common situation is line fences acts: land registrars appoint provincial judges as “fence viewers” in fence maintenance disputes. In those cases, judges don’t have the usual immunities (ex. can’t sue a judge for performing a judicial function, can sue him for negligently acting as a statutory designate). There is a phenomenon of “borrowing” of judges as they are seen as impartial. As an aside, this cannot be done constitutionally in the US (although done with Jackson, prosecutor at Nuremberg, and Warren, who headed the Kennedy assassination inquiry).

Each province has something like a Pregnant Mares Urine Farms Act (urine used to culture penicillin). In the AIA, the target is the health of the bees, not public health (can boil the honey). For penicillin, the rationale is more public health. In neither case was monopoly a motive.

True / false questions on AIA: 1-F (unless first inspection was negligent); 2-F (need approval of PA); 3-F (s. 7); 4-T (s. 12); 5-F (s. 3); 6-F (s. 5(2)); 7-F (only LG in C can make regulations); 8-F (s. 2); 9-T (broad definition of bee-keeper); 10-F (his name, s. 3.1); 11-F (s. 11(1)); 12-F (only suspension or removal). 15

B. Official and Unofficial Interpretations

A number of themes recur in Hartog’s article. Who were the addressees of the municipal ordinance forbidding pigs in NYC? Certainly the “pig lawyers”, “bourgeois lawyers”, city lawyers / prosecutors, homeless shelter lawyers. The judges were also adressees (mostly former bourgeois or city lawyers). Why isn’t the statue addressed towards pig holders? There was an assumption that pig owners didn’t pay attention or couldn’t read. Ironically, most legislation is not drafted for the people who are ‘regulated’.

What do pig lawyers tell there client? Basically that it’s OK, as there are few prosecutions and even reimbursements for seized pigs. The lawyers extrapolate from past and related experience. Was it a free for all, civil disobedience for pig owners? Hartog speculates that there were customary norms. Presumably, aggressive pigs were not appropriate.

There appears to be a conflict between the written law of NYC and the customary law of pig owners. Ironically, court verdicts favoured customary law. Influence of jurors may have played a part, but according to Macdonald it was more a common law vs. statute conflict. There may also have been a sense that pigs were useful in certain neighbourhoods without street cleaning.

Twenty years later, judges changed the interpretation and came to the conclusion that the municipal ordinance had to be followed. The interpretation was driven by the facts on the ground, the context – larger city, improvements in transportation (ship swine by railway). None of this is in the ordinance itself, but rather in judicial reasoning. A statute is always anchored in some set of pre-existing practices.

C. Methods of interpretation

That said, lawyers still have to read and interpret statutes. It often comes down to the letter / spirit and liberal / restrictive debates. “No person shall sleep on a bench in a Metro station in Montreal.” Macdonald falls asleep while waiting for a train. Or he brings a sleeping bag, puts eyeshades on but has not fallen asleep yet. Literally, the first case is an infringement and not the second. In terms of purpose, the second is but the first one isn’t. Probably neither person would be convicted: in the first case the bowtie is pleasing, in the second case offences are interpreted restrictively. Suppose that the hypothesis was not a prohibition but a benefit. Interpretation would be broad.

These rules, canons of interpretation, were devised by courts. Famous ones are: expressio unius est exclusio alterius (one mentioned excludes others), ejusdem generis (generic category). There are hundreds such maxims created by courts, but should they control the interpretation of statutory delegates and public officials?

D. Controlling interpretation

Legislatures very often try hard to get courts to interpret words in a certain way. Sometimes, legislatures tries to control interpretation within a statute: preamble articulating the spirit of a statute (s. 13, Interpretation Act), titles (Act Respecting Apportionment in the Legislature of Ontario or Fewer Politicians Act; Prevention of Unionization Act!), substantive definitions, headings. 16

Beyond internal controls, there are external controls: rules on how to read a statute (Interpretation Acts). S. 10 of the federal Interpretation Act say that the law “always speaks” and tells courts that spirit, intent and meaning in the present (read statute as applying to the present) are paramount. There also are judicial canons, which courts deem legislatures to know. One of the main constraints on interpretation is that the legislature usually says who is to interpret the statute (ex. superior court used as federal court for bankruptcy), the only limit being s. 96. The federal Parliament can create courts, it and provincial legislatures can create tribunals.

Finally, the legislature is choosing who will interpret the statute. A court will mean lawyers, who have a certain understanding of their role, a certain knowledge, a certain drive, etc. The story is different for a labour board. Is it no surprise that the Faculty of Law has the most, and the most detailed, academic regulations. The Faculty of Social Work regulations are a different story… Different patterns of understanding associate with different disciplines. Legislatures perform a sort of forum shopping.

What went wrong in Singapore? An extremely literal, contra spirit, interpretation of a statute was used. Also there are safeguards as to what can be done at a polling station, so the purpose was supposedly respected (although officers were appointed by the party in power!). Why didn’t the legislature foresee this? How much context does the legislative function require? Do we expect courts to know the context of everything? This is an impossible task. There is always a limited amount of context judges are presumed to know. But judges often need to be educated about a specific issue.

There is a belief that if the legislature gets it right, the context “will look after itself”. Parliaments appoint statutory delegates when they want something else: specialized knowledge, fact-sensitive interpretation. Nonetheless, in a constitutional democracy, courts have ultimate interpretative authority. Privative clauses are more about giving experts a first kick at the can.

May 17th, 2006

Class 7: The Ontario Human Rights Commission as a Creature of Statute

A. Recap of Previous Class

A post on WebCT had to do with the relationship between written text and interpretative communities. The “Pigs and Positivism” article was a way to show that there are normative systems that compete with formal texts. This doesn’t only exist in the realm of public law, but also in private law, ex. contracts (for ex. in manufacturing clusters). When we think about the delegation of statutory authority, there are at least 5 epistemic communities involved: - Legislature and its members when the statute was enacted. - Courts as they exist whenever any case comes before them. - Statutory delegates (ex. Provincial Apiarist). - Community of regulates (ex. bee-keepers). - General public. Each of these communities have experiences which bear on how the statute is read. There is no magical formula. Three collateral effects of this are: 1- legislatures deploy techniques to direct interpreters to what was intended by the words in a text and legislatures take into account the way courts tend to interpret statutes; 2- each community reads the text in a 17 particular way, but there can be ‘dissenters’ within any of them; 3- when the addressee of a text confronts it, this is not an exercise of literal reading, each action involves interpretation. We can’t assume any community will interpret a text in the way the legislature did (assuming it knew the meaning of what it was passing). Legal interpretation is iterative. “The system will not necessarily work the way it was designed.”

Does there have to be a hammer for there to be normativity? Is a “do not” needed to influence behaviour? Fairy tales are meant to get children to reflect, children are not just raised with a rule-book and with a ruler. Size of the group is also an important factor, the bigger the group gets, the more formal rules are needed. This doesn’t mean that there are no common values in even large groups.

“The final interpreter of legislation in Canada is the Canadian public.” - Rod Macdonald

B. Origin and Rationale for the HRC

The HRCode apparently has explicit purposes and aspirations attached to it: value- affirming agency. What lead legislatures to create HRCs? There was a lack of enforcement, previously there was just a tort system, the process was put in motion by the affected person. Courts also favoured those with most resources, not those who suffered discrimination. There was no common law on the subject, as there was insufficient judicial support for this: no tort of discrimination. Solutions that courts can provide are limited, and there must be ‘winners and losers’. Courts also can’t investigate, start education programs or look at systemic problems. Judges also came from wealthy white backgrounds, which did not predispose them to sensitivity (although MacKay J. was in that club).

Before the HRC was created, there was piecemeal legislation with the same kinds of principles. Interestingly, the grounds of discrimination varied from statute to statute and the responsible minister varied. Discrimination was not a transversal theme, it was about housing, labour, services, etc. The big change of the HRC was the consolidation in one statute with discrimination as a central theme.

Many ‘special interest groups’ were trying to advance an agenda of non-discrimination in 1950’s Ontario. Leslie Frost, who was ‘the government of Ontario’ had an important role to play in creation of the HRC. He realized that there was some political interest, but he mostly was lobbied hard.

Hunter was in favour of the HRC until the early 1970’s. By 2001, he completely changed his mind and became a pre-eminent opponent. He was the first general council of the HRC. He also drafted the Canadian Human Rights Act.

The HRC doesn’t look like the AIA. It is not called an act, but rather a code. It has the same normative status under the Constitution, but the legislature nonetheless called it a code. “Code” gives a sense of comprehensiveness, rather than a patch on the common law. It also has a preamble, which reads like a mission statement, a statement of aspiration. Over time, the original 7 sections were supplemented. Freedom from harassment was added to freedom from discrimination.

Part I is written in an affirmative way (“every person has the right to…” rather than “no person shall”). It doesn’t start with definitions, but rather with the substance; same story 18 for the Charter. The idea is to attain some semiotic advantage. Ironically, the definitions don’t sound like such universal principles. For ex., age is between 18 and 65, although a new definition just says age, ‘notwithstanding’ done in specific statute. This is not accidental, the way exceptions are managed was originally that all exceptions were in the HRC, which is now revisited.

C. Structure and Process

The HRC also creates the Human Rights Commission. The fact that it was done in the same statute is a signal that enforcement would happen. It also elevates the status of the Commission. It also raises the stakes for anyone wanting to abolish it. Also, it was a strong signal that the HRC was no mainly to be interpreted by courts but rather by the Commission. Hunter quit the Commission in 1977, claiming that it had become proprietary and self- aggrandizing. In a report, it suggested a draft act that gave its structure more importance.

In 1996, the administrative body (board of inquiry) was transformed into a HR Tribunal. Boards were a “gravy train for law professors” who were not independent and had an incentive to find infringement, whereas tribunals have independent members.

S. 34 says that there are reasons the Commission may not entertain a claim: for ex., if another statute applies (labour relations), bad faith or vexatious, no jurisdiction, 6 month prescription. There is a broad discretion to proceed. About 8,000 complaints are filed yearly. It has the staff to handle about 200, but feels it has jurisdiction and grounds to proceed on about 2,000. How does it decide which 200 are to be entertained? Basically the most egregious ones, which are selected on the basis of profile, whether there are clear ‘winners’, minor ones to push existing rules.

The Commission decides how to rank the cases on the basis of internal policies. This causes the problem of adaptive behaviour. There are also a lot of judicial review applications, which end up being very costly.

May 18th, 2006

Class 8: Intragovernmental Conversations (Prof. Baker)

It is hard to even list all administrative delegates in Canada. Our case studies were chosen as somewhat representative cases of different instruments. The Ontario HRC functioned as a model for all the Commissions that followed. Much was written about it, especially by Ian Hunter.

Much rides on the interpretation of text. In Bell, everything turned around the meaning of “self-contained unit”. This highlighted the power struggle between legislature, agency and courts. The text framed arguments that could not really be made directly.

The HRC is a ‘government in miniature’. S. 29 is key: “It is the function of the Commission…”: forward rights, promote rights, affirmative action, research, revision of statutes, regulations and programs, deal with conflict situations, investigations, etc. The mandate is to shift consciousness; it is also hugely discretionary. This is very much in the realm of distributive justice – the emphasis is systemic and not adversarial. Resources are not unlimited, however. 19

Nowhere in the 48 s. of the HR Code is there a roadmap of the HR Commission. It is established by s. 27 rather than s. 1. The HRC is responsible to the Minister of Labour. It has a chair and a vice-chair, as well as employees who are civil servants. It also has a certain number of divisions, ex. ‘race relations’. S. 32 suggests that there has to be intake officers for complaints. S. 33 suggests the need for investigators, which are given broad powers. Mediators / negotiators (s. 34), boards of inquiry (s. 35), regulations made by the LG in C (s. 38) are also needed. Various functions of conventional government have been included under one roof: quasi-judicial, intake, policing, rule-making, quasi-legislation, reporting, mediation…

Hunter observed that the HRC had been around for 10 years before Bell happened. This case was the first successful application of judicial review. Nonetheless, the HRC dealt with thousands of cases in that decade. On the basis of the enabling statute, the HRC is responsible to the government for its every move.

There’s obviously a theme of institutional self-interest in Bell and even in Bhadauria: turf warfare. The pious hope of provincial legislatures was that HRCs would enjoy enough gradual success that they would eventually wither away. However, the HRC has over time committed most of its budget to treatment of individual complaints rather than to the broader, systemic mandate. Each time some complaints dropped off, the HRC heavily lobbied for extension of its jurisdiction. In 1982, harassment, sexual orientation, constructive discrimination and affirmative action were added. The HRC is now lobbying to have jurisdiction over hate literature. Some arrogance develops in agencies just like in courts. Hunter calls the HRC staff “human rights zealots”.

Bell rented the top two floors of his house. There are no locked doors between the space he occupies and the rented space, Bell said he preferred mature tenants. McKay was a black Jamaican who was told, falsely, that it was occupied. He made a complaint to the HRC. The HRC told Bell he had contravened. Bell’s lawyer made an application for a writ of prohibition claiming that the HRC exceeded its jurisdiction, which at that time was limited to “self- contained dwelling units”. These words became the central of the “who should decide struggle”. Ultimately, Bell’s freedom of contract and right to control his home was preferred.

The Globe & Mail article said in reaction to the trial judgement that Bell’s human rights were “magnificently defended”, even though the HRC’s jurisdiction was limited! Following the SCC judgement, it was said that Bell was “rescued” and that the intentions of the scheme “pave the road to hell”. It was also said that the HRC’s wide powers were “offensive to democratic principles” and civil rights. “Consciousness was not moving very fast.” - Baker. Ironically, by the time McKay lost, he had been back in Jamaica for a few years.

In good Diceyan form, the Constitution is based on two principles: parliamentary democracy and sovereignty, and rule of law. These two ideas often turn out to be difficult to harmonize and somewhat counter-balancing. In Dicey’s view, the source of individual rights was private law, public law was merely reified private law. He also advocated heavy-handed presumptions in favour of individual contract and property rights. The plain-meaning rule was a sort of non-entrenched Bill of Rights. In that respect, courts get the last word. This view allowed courts to arrogate the power to review acts of legislative delegates – this power was pretty much invented as an answer to the threats to the established order. This was the push-me-push-you phenomenon in Bell. 20

The CL provides for no right of appeal beyond superior courts. But appellate courts have the entitlement of reviewing actions of legislative delegates on basis of jurisdiction (and also natural justice).

Every time a statute is created to displace CL rules, courts are displaced. Progressively, courts have found themselves increasingly relegated to the interstices of administrative bodies. For obvious reasons, courts are not pleased. The current CJ of Ontario said in a speech that they are “autocratic, arbitrary and irresponsible bodies” and added that “security of life and property” were paramount (“The national safety is in danger”!!!). There is a sense that McKay and Bell were tokens, coincidental for an important underlying debate. Escalation in privative clause drafting was ineffective, even when the BC Labour Relations Board legislation said that “this agency has exclusive jurisdiction to determine its own jurisdiction”.

Admin pro gives the worms-eye, inside-out view of administrative action. Judicial review gives the birds-eye, outside-in view of courts’ sanctions of administrative action when something ‘goes wrong’. Late 19th C. courts decided that they could review the behaviour of any inferior governmental operator. They dressed up this newly found power in seven prerogative writs (public law equivalent of debt, detinue, trespass, etc.): certiorari, prohibition, quo warranto, mandamus, habeas corpus, declaration / injunction (Nabisco prerogative writs). Each of these writs have a special function: certiorari to quash (in the US, certiorari is exercised with respect to an inferior tribunal), prohibition to stop an action pre- emptively, quo warranto under what authority (19th C company law developed through this, special act incorporations at the time), mandamus mandate action, habeas corpus compel release, declaration and injunction as in private law. Federally, ss. 18 and 28 of the Federal Court Act talks about “applications in the nature of judicial review”; Quebec and Ontario also have reformed the writ system. Courts still often use the old language, though.

Three questions as a reviewing court: Constitutional jurisdiction to delegate the power to the agency? If yes, is the particular power asserted by the agency within the scope of delegation specified in its enabling statute? If yes, were the rules of natural justice followed (notice, audi alteram partem, counsel, written decision, etc. basically “act like a court”, procedural issues blur with substantive ones)? Roncarelli v. Duplessis says “administrative decision makers have to behave reasonably”. Nicholson says that “the process has to be fair (notice, hearing, explanation). CUPE v. NB says that “reviewing courts should defer to agencies unless their action is patently unreasonable”. Baker says that reasonability, fairness and deference applies to all administrative action. This was the 10-minute version of Judicial Review.

There are many other accountability mechanisms than courts! Cabinet, Auditor General, etc. Knee-jerk judicial review reactions should be controlled. Yet, over the last 50 years, the supervisory ability of courts has been greatly extended. The effect of many ‘modernizations’ have increased courts’ jurisdiction.

In Bell, the ‘warfare’ escalated so quickly that the HRC’s own stare decisis on the question was not even considered. Ironically, Tarnopolsky and Krever, who had decided as boards of inquiry that cases such as Bell’s were within the HRC’s jurisdiction, where appointed respectively to the OCA and the Ontario Supreme Court. Interestingly, the expression “self- contained dwelling unit” was later removed by the Ontario Legislature. In Bell, the SCC was 21 concerned that there was sort of a built-in institutional bias inside the HRC in favour of plaintiffs.

Managing human rights is not like sending out an apiary inspector. The change has to be progressive and managed. Legislative zeal can end up being counter-productive. This is a large part of Hunter’s critique. In BC, the Social Credit government abolished the HRC in the early 1980’s and replaced it by a one section statute creating a statutory tort of discrimination. Ontario still has an HRC. Quebec also does but delictual action is also possible. Different macro-instrumental choices generate different results.

Post-Charter, Badhauria may have turned out different. At the time Laskin, was extremely nervous about the outcome if courts got control. Maybe Laskin is too much of a fan of administrative processes. They too are imperfect: Badhauria did complain to the HRC 6-8 times, which did not yield anything.

May 23rd, 2006

PART III: ALLOCATIVE, REDISTRIBUTIVE AND OVERSIGHT PROCESSES: DISCRETION

Class 9: L’État-Providence and Discretion

A. Recap of Previous Class

Macdonald emphasizes the background note on intragovernmental ‘conversations’. Back to the idea of accountability and review… As a matter of institutional design, how can it be ensured that a decider makes a decision to the best of his abilities and furthering the goal of the statute / regulation? One will first think of incentives and second of corrective or punitive measures. The people have to be well chosen, trained, have positive incentive and a manageable workload, knowledge has to be shared through time. Sometimes, mistakes are made, which call for review: - In house review. Reconsideration first by the same decision-maker, then up the hierarchical chain. Most large organisations have built in accountability / appeal structures. - Out house review. This doesn’t necessarily mean courts, it may be specialized administrative tribunals, Cabinet, ombudsperson, but also direct statutory appeals to courts, judicial review. - De novo review. This involves going outside the framework: media, UN HRC, MP, lobby, get Parliament to change the law. These recourses may seem very unusual, but they are actually quite standard in Western countries. This is a challenge to the rule structure, not to the application of the rules. A case like Bell is an important but rather small fraction of the whole structure of administrative accountability.

B. Program expenditures

Our introduction to this field will be the welfare regime. Most democratically elected governments get elected by spending money on sufficiently large constituencies. Realpolitik involves taxing ‘enemies’, either directly or through law (see below). Taxation and subsidy 22 are tools of regulation. Taxing wealth, consumption and income, which are either proportional or flat, continuous or one-off, aiming at different actors does not have the same effects.

In addition to across-the-board taxation, there is so-called ‘tax expenditure’. These are targeted tax exemptions to favour narrow constituencies. Ex.: GST rebates for low-income earners, deductions for RRSP contributions, income tax breaks for settling researchers in Quebec, tariffs. Frequently, they happen through contractual agreements between governments and particular people, usually businesses (one ex. is waivers of Bill 101 in Quebec for some executives!). Tax breaks for businesses are common industrial strategy.

The other side is direct expenditure, subsidy. There are both direct and indirect forms of subsidy. Direct subsidy is giving money directly, providing cheap loans, loan insurance. Indirect forms of subsidies are probably the most pervasive: State program to look after something paid for by employers elsewhere (ex. medicare), limit application of EPA or Labour Code, government procurement, exclude tort liability, affirmative action targets to obtain money (ex. universities that want money from SSHRC), create property rights (pharmaceutical patents), quotas and tariffs in some cases, etc. The idea is to externalise some costs of doing business outside of businesses (workers, government, environment). Almost every government decision can be categorized as taxation or subsidy.

The range of instruments can be plotted against the targets of government: food, shelter, health, education, child rearing, disability, employment, retirement, income support, welfare. This is most of the people-oriented social policy.

C. Social Welfare State – L’État-Providence

Imagine the Minister of Finance having an extra $100 million in coffers to spend. Possibilities are health, education, income support, welfare. Results in the class are health – 12 (40% 2003 class), education – 21 (50%), income support – 4 (10%), welfare – 6 (0%). Welfare does not belong in the list in a way, because it is narrowly focussed, whereas health, education and income support are at least designed to be universal. The facts may be different than what the design intended: universal looking legislation can produce unequal effects (efficacy / effectivity chasm), for ex. maybe education is not as universal. Macdonald’s thesis is that these programs are trickle-up / tornado up economics which disproportionately do not advantage the poor.

What is it about ‘universalistic’ programs that makes them more attractive in a Faculty of law, beyond mere self interest? One possibility is that these programs seem to have an ulterior objective: investment in better health, literacy, etc. However, the image of welfare is that it is not producing any social goal. Interestingly, all social legislation such as the Canada Health Act have preambles, not a single welfare statute does. What would have to be said about welfare for it to enter the cosmology of the other programs?

Images of welfare Job re-entry, employability Support (not tied) Shame, guilt Charity (for a good person, there is a sinner) Kaldor-Hicks efficiency (buy out the losers) Entitlement Conditional (deserving poor) Unconditional (wage) First resort Last resort Temporary, transitional (ex gratia) Permanent (interest free with clawback) 23

Deferred investment

For market-types, the justification of welfare is buying out efficiency gains. For socialists, the theory is much more redistributive (rawlsian justice, pay out losses and advantage least well- off most) – this is the idea of progressive income tax. If the dominant image of welfare was redistributive or K-H efficiency, many other understandings of welfare would not be part of public discourse. Other reasons are appearance of productivity, valuation of success and independence, etc.

D. Discretionary Justice

Judy’s story… She’s a lawyer but can’t hold a job. Her family is pressuring her to become more independent, as she lives with her mother. She moves out and applies for welfare. Which arguments could be used under s. 12 of the Alberta act? She’s tried to work. She’s a grown adult. It’s more efficient. There is a general rule. Attempt to provide social welfare on the cheap. It’s tantamount to indirect taxation. When Macdonald pled this case in Quebec, he tried all of these arguments unsuccessfully and got hostile answers. We also look at the case of the alcoholic employee not being disciplined. Ironically, discretion is exercised in this last case even if it is non-existent legally.

Rawls or Kaldor-Hicks are not in the legislation: we find charity, temporary, condititional, last resort… There is a detailed regulatory regime overlain with broad discretion and little guidance as to how to use it. Every decision involves discretion, none is automatic. The challenge is to organize the exercise of discretion. It always exists, but the outcome varies.

May 24th, 2006

Class 10: Criminal Injuries Compensation as a Redistributive Process

A. Recap of Previous Class

A good way to drive home yesterday’s lessons are to contrast student aid and welfare. How would we organise a welfare scheme if we were to adopt the student aid scheme and vice- versa?

Tax expenditures and subsidies in student aid: subsidized tuition – infrastructure – institutions, tax credit on interest on student loan, tuition deduction, room and board deduction, grants, interest-free loans, scholarships, subsidized transit, RESPs, RRSPs.

Compare this to welfare: one program and minister’s discretion. Perhaps one could re-design the welfare system in smaller compartments. Even collateral programs, such as subsidized housing, fall under minister’s discretion.

B. Allocation and Discretion

Discretion also pervades criminal injuries compensation systems. Many of the formal controls on discretion are present in CIC schemes (ex. political accountability), but the informal controls (ex. policy manuals) are simply not there, as the minister often has full discretion. To what extent building an infrastructure, such as a commission, agency or board, is more likely to create an informal normativity? 24

For present purposes, we will assume that the offender has been convicted. We can think of this from the perspective of the victim and from the perspective of the offender. A considerable shift has occurred in the last 25-30 years. Three decades ago, the victim was a mere token in a criminal trial and sentencing process, with no services or support. Beginning with criminal injuries compensation, the place of the victim got larger in the criminal nexus.

The five objectives of punishment in criminal law are deterrence, rehabilitation, retribution, prevention and denunciation (a recent add-on). The tools to do this are capital punishment, torture, corporal punishment, forced labour, stocks, solitary confinement, jail, banishment, house arrest, fines, community service, restitution, psychological therapy. The list is long. These types of activities don’t line up equally with all the principles of punishment, they mostly aim at retribution (which dominates in polls).

How many of these speak to compensation? Few, restitution (provided for in the Criminal Code) and maybe community service. Other options are tort, compensation fund (with or without moral hazard component), self-insurance. Subsidized prosecution and police work are a form of service to victims, although not compensation.

The problem with tort is that when the defendant is impecunious, that is the rationing mechanism. In insurance, it’s affordability, deductible and cap (contractual limits). For State compensation programs, it’s caps, moral hazards, (hopefully targeted) rationing of payouts (file in January!).

C. Victim Services and Moral Hazard

There is now a relatively broad range of “victim services”. The trial process has also been somewhat modified (ex. victim impact statements). There is a move from compensation as corrective justice to distributive justice. The practice, unfortunately, is that State mechanisms are drastically underfunded.

The Dalton case is there to show how courts and boards may have a different perspective on moral hazard.

D. Problem: Saskatchewan Victims of Crime Act

Committee #1: s. 14(1) (identity of decision-maker) Good to keep it from civil and criminal trials. So the question is maintaining the minister in his position or creating some board. One is more flexible, the other is theoretically less discretionary. Need to know which resources are available, what the caseload is, do a comparison of other jurisdictions.

Committee #2: s. 16 (scope of discretion) Create an actuarial formula superimposed over a consistent shopping list. Workers’ compensation regimes have actuarial tables (problem of inflation). Torts work in a very different fashion. Eligibility requirements may be reformed (moral hazard?).

Committee #3: s. 7 / 3-5 regulations (financing) Us! See sheet. Macdonald mentions the proposed taxes on beer, guns, violent movies, expropriation of profits from depiction of crime. 25

Committee #4: s. 8(1) ($25,000 cap) Does the cap meet the need of most victims? If so, discretion to occasionally go beyond it would be appropriate. If not, re-evaluation would be necessary. The purpose of compensation would have to be considered. Differentiating on the basis of crime may be done. The tort system may give some sense of what is needed (but the awards are unbearable for the public scheme, can’t have a one-size fits all).

Committee #5: s. 8(2)-(3) (classes of eligible monetary losses) Adding pain and suffering, ‘reasonable’ (rather than ‘exceptional’) counselling, don’t add economic losses ($140B of Enron!). Past decisions would be needed to determine interpretation of sections.

Committee #6: s. 13(1)-15 (filing conditions) Unreported crime is a problem. The initial frame of mind was a random mugging – it works for this but doesn’t for domestic violence. But compensation can also be seen as an incentive for reporting.

Committee #7 (offences for which compensation is payable) Currently, only criminal (no regulatory) offences are covered. Another issue is whether economic crimes should be included. An issue is also that the surcharge crimes don’t map exactly the compensable crimes (participating in a riot, setting a trap, bestiality). Could a surcharge on crime against animals be paid in to the SPCA? As of the late 1990’s, prevention and other related programs have been included in such schemes.

Committee #8 (use of the victim’s fund) Guidelines or some structure to frame the minister’s discretion would be useful. A consultative committee could also serve this function (more and more common in statutes).

May 25th, 2006

Class 11: The Public Protector: Formal and Informal Accountability

A. Recap of Previous Class

One significant implicit line of inquiry is “if you don’t know what you’re talking about, you can’t understand the statutory regime”. The assumption of law floating disconnected from fields of human endeavour is wrong. If we are to have judicial review of administrative agencies, knowledge is paramount. Specialized courts are useful for this.

There has been a significant re-think of the criminal justice process, moving away from offenders and towards victims. At the same time, there has been a great re-think of and move away from tort law (most comprehensive ex. in New Zealand, no longer any law of tort for personal injury from 1971 to 1998, now some tort law is back).

The original compensation schemes were set up in England under the royal prerogative: completely discretionary ex gratia payments by the Lord Chancellor’s office. In Canada, it is done either through boards and agencies or through a minister, provided for in a statute.

Major policy questions seen yesterday: 26

- Setting up a scheme on an ad hoc basis or as a permanent structure (agency or giving authority to a minister)? - Is compensation a price list or is it governed by general principles with discretion to the decision-maker? - Is the scheme open-ended (like torts) or capped? - What types of damage are covered – personal injury or property damage / economic loss?

B. Why an Ombudsman?

This administrative process is directed to public administration itself as a regulatory field. Why doesn’t the Public Protector Act have a preamble? Not a single similar statute in Canada has a preamble, suggesting that it is seen as in-house mechanics.

Both the appointment and the reporting make the Ombudsman a parliamentary commissioner. A 2/3 majority is required, every initial appointment in Quebec has been unanimous. Harper should have made his ‘patronage commissioner’ a parliamentary appointee. The PP can make individual reports about specific persons or structures. There is also an annual report. All of this goes to the National Assembly directly. In Ontario, the HRC has been much criticized by the Ombudsman!

C. Character of the Institution

The Ombudsman has no executive power, can’t order any action. He can only investigate, negotiate, conciliate. This involves vast discretion. There is a general public misperception of ombudsmen in Canada: many people think s/he can right all wrongs. It’s also difficult for non-lawyers to see the trichotomy of the PP: illegal action – judicial remedy and ombudsman, maladministration – no judicial review but ombudsman, I’m unhappy – no recourse. Drawing the lines between those is difficult. Ombudsmen have a large education mandate.

S. 26.1 of the Public Protector Act lists the grounds for intervention. Of the five, three (illegal, abuse of discretion, error of fact or law) give rise to judicial review, two do not (unreasonable or unjust, negligence). The language is cast very broadly because the targets of the Ombudsman are broad.

Millions of events occur annually over which the Ombudsman has jurisdiction. Obviously, the Ombudsman is not supposed to have close connection to all these decisions. Hence the exclusions: other available legal remedy, limitation period lapsed, persons bound to act judicially (courts, tribunals – separation of powers), cabinet officers or deputy ministers in political functions, within one year of event.

The design of the process is totally discretionary (s. 19(1)). It’s a ‘soft’ process (ss. 23-25) to be done first in private and through cooperation if possible. The Ombudsman is also protected by many immunities (no damages, disclosure, testimony, judicial review, ss. 30-35).

D. Outcomes, Process, Qualities

The Ombudsman’s sanction is only publicity: requests, reports and public statements. He has no power to order any redress. There are actually heavy constraints on the Ombudsman’s rhetorical power: can’t make public statements every second day. 27

Who should be picked to be Ombudsman? Should it be a lawyer, i.e. proficient in litigation, being able to recognize illegal action, knowledge of public law, commitment to deontological practice, giving legal advice, advocacy skills, self-assurance / boat-rocking, practical, representation of individual clients? By comparison, ‘good’ public servants à la Willis should be discrete, team players, focused on the system, have a different set of ethics, concerned with action rather than with jurisdiction, conciliators, negotiators. Admittedly, these are ideal types.

Where would one look first for an ombudsman? The PPA gives guidance as to what this person’s mandate is. It depends on the circumstances: public servant for new Nunavut administration, lawyer for the long-standing government of Nova Scotia. Historically, first ombudsmen were lawyers, the second were public servants, the third were lawyers, etc. The shelf life of an ombudsman is about one term, as two opposite imperatives are balanced. Do you want a person to solve a problem or fix a system? Sounds like a large law firm ‘economically hedged’ with M&A and insolvency. Maybe the reason there is no preamble in the PPA is that the purpose is uncertain.

Shopping list of quality: impartial, independent, credible, solution-oriented, good at diagnostic, moderate ego.

E. List of Alternatives

Within the public service, there are many Ombudsman-like processes: Auditor General, Privacy Commissioner, Official Languages Commissioner, Military Ombudsman, etc. All of these are public structures; also ad hoc structures, such as public inquiries (case and systemic oriented). Whistle blowing legislation, suggestion boxes, tort law, BBBs, The Fifth Estate, company ombudsmen, ISO and other private operations also have a role to play. The role of the Ombudsman will depend on what other structures exist… only one piece of the puzzle.

F. Maladministration

What is maladministration? Lack of transparency, redundancy, lack of mandate, rudeness, unresponsiveness, lack of qualification, dishonest, delay, nepotism, buck-passing (‘not my job’), lack of coordination, partisanship, red tape, inflexibility, personality problems, etc. These phenomena are everywhere. How many structures are immune? None. There are many such problems below the radar screen and much work remains in this area.

May 29th, 2006

PART IV: ALLOCATIVE, REDISTRIBUTIVE AND OVERSIGHT PROCESSES: DISCRETION

Class 12: Statutory Instruments and Regulation: Ex ante Oversight

A. Recap of Previous Class

A few issues left in the air about the PP… First, it was left unsaid why it was only in the 1960’s that this idea came up in CL jurisdictions. From the early 19th C. in Scandinavia and 28 the early 1860’s in France, equivalent ‘ombudsman’ structures existed. Rowey points out that it was assumed in a regime were the executive was responsible to Parliament that many oversight functions would be carried on by MPs. Two things undermined the MPs’ capacity to do this: party discipline, decline in ministerial responsibility (ministers no longer resign if anything goes wrong). Second, who exactly is the PP for? Even in its short existence, the institution has changed significantly. Initially, it was seen as a surrogate MP, today it is seen as also having responsibilities towards the civil service and the government. Hence the tension: fix the system or solve the problem?

B. Nature of Normativity

What is the range of institutions and processes by which, in any legal system, normativity is generated or expounded? Seen in Foundations. Macdonald suggests that four basic types of normativity exist in his Background note: textual instruments designed by institutions (ex. statutes), inferred instruments designed by institutions (ex. CL precedents), unwritten precise non-institutional rules (ex. customs, trade standards, rules of thumb), unwritten broad non- institutional rules (ex. good faith, rule of law, fundamental justice).