TORN IN TWO-EXHIBITION AT BOSTON PUBLIC LIBARY

150th anniversary of the American civil war (1861-1866)

-Teacher’s introduction

- Students arranged in groups

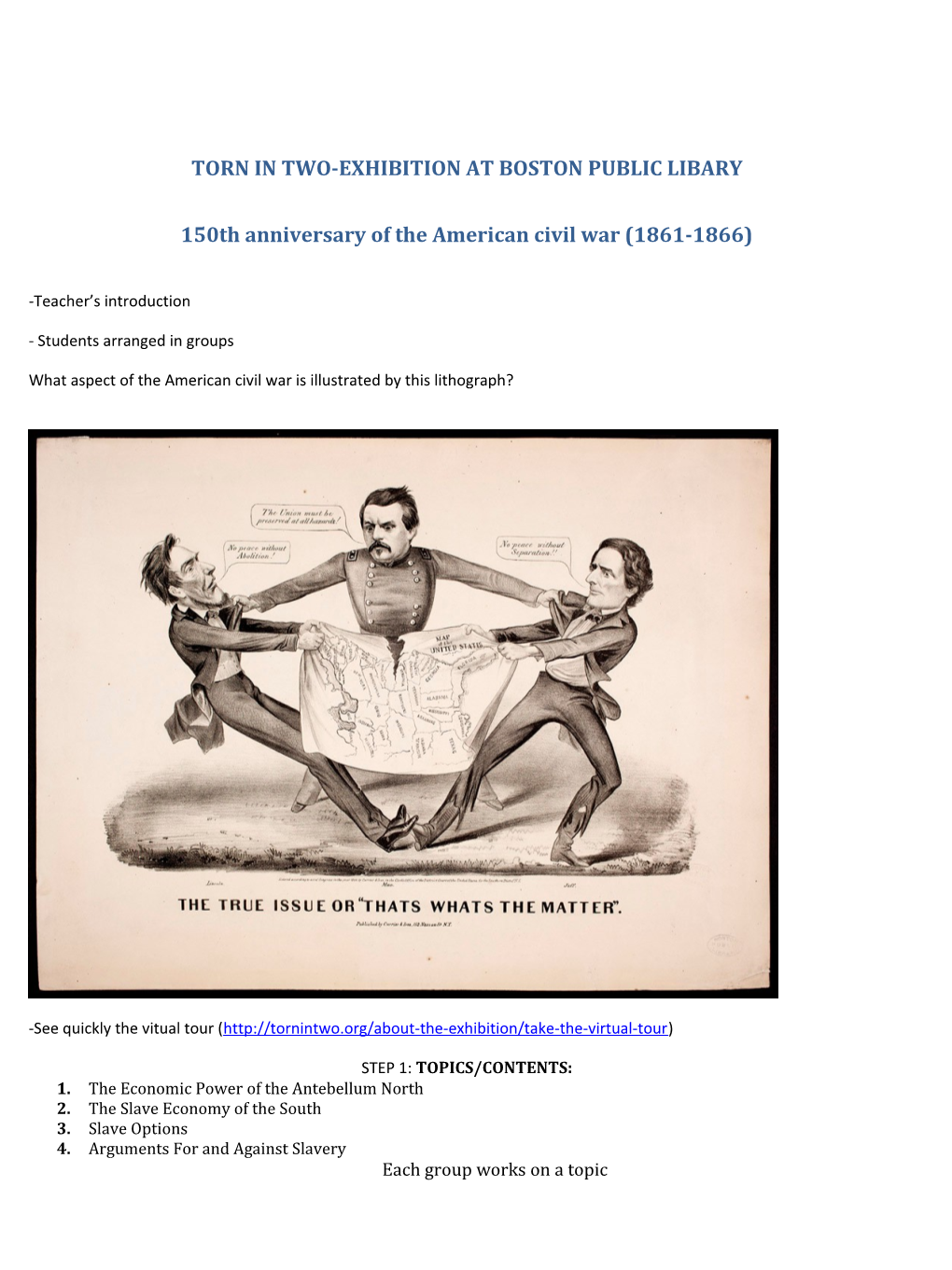

What aspect of the American civil war is illustrated by this lithograph?

-See quickly the vitual tour (http://tornintwo.org/about-the-exhibition/take-the-virtual-tour)

STEP 1: TOPICS/CONTENTS: 1. The Economic Power of the Antebellum North 2. The Slave Economy of the South 3. Slave Options 4. Arguments For and Against Slavery Each group works on a topic Group 1: The Economic Power of the Antebellum North

By the 1850s, there was a great deal of wealth in the Northern and Mid‐Western states. There was also the

promise of much more wealth, as the slogan of the newly formed Republican Party promised: Free Soil, Free Labor, and Free Men. But the fate of the Western territories was hotly contested and it would be the horrific events of the Civil War that would determine their status. What was the situation of these Northen States on the eve of succession?

1. Analyse the Map of Freedom and Slavery (http://maps.bpl.org/details_14346). What do the Red and Blue states represent? Why are the Yellow areas the most important when this map was made in 1856? What do the data at the bottom reveal of :

. Value of land (include farms, livestock, acres of improved land) . Educational Information (include newspaper circulation, library volumes) . Manufacturing Capital . Transportation information (include railroad and canal miles)

You may present your results in a graph, chart or other visual medium.

2. Now discuss the value of transportation to manufacturing and look at the 1859 Railroad Map (http://maps.bpl.org/details_14344). What differences do you notice between the North and South? How does this affect economic growth? How will this affect the development of the war?

3. Now read carefully the notes from Wikipedia in the other file about the antebellum period.

4. Choose a speaker and report to the class the results of the discussion (point 1,2,3) Group 2: The Slave Economy of the South

There was a great deal of wealth in the South. If history is about choices, the planter aristocracy committed the South to an agricultural society in which wealth was tied to the land and a forced system of labor. The stark reality that such a small number of individuals that affected so many is worth exploring.

Read carefully the people’s identities of James Harrison, Tilly Johnson, Rebecca Parrish and Isaiah Wilkes (http://www.tornintwo.org/about-the-exhibition/take-the-virtual-tour) and find out the plantation owners’ view/s on slavery and war. Opposingly, point out the slaves’ views on their condition and on the war. Choose a speaker and report to the class.

Group 3: Slave options

To make sense of the history of the Civil War and slavery, our approach is to access this topic through this notion of choice. Who was making the decisions? How did so few people decide the destiny of so many? It is also imperative to recognize the power of the seemingly powerless to make choices about that which they could, to take chances, to control those aspects of their lives that they could.

1.Ask and answer each other these questions:

What does it mean to be free? What choices do you get to make in your life? What happens to people who do not get to make choices? Might they decide to take the law into their own hands (to act alone)?

Be ready to report the results.

1. Now create a chart with several columns. Label the first column ME. The next column could be for Amos, a 14 year old slave in 1850 South Carolina. The third could be for Mrs. Jones, the wife of Amos’ owner. You can read the texts below (“SLAVE LIFE”) for reference.

Answer YES or NO to the following: a. Do you go to school? b. Do you live with your family? c. Are you allowed to read? d.When you grow up, could you be President of your country? e. When you grow up, will you be allowed to get married? f. When you grow up, will you buy a house? G. Can you vote?

ME AMOS MRS JONES SLAVE LIFE

The African American slave society in the antebellum South (1807--1860) was unique among New World slave systems. In the United States, the slave population not only sustained itself; it expanded exponentially. In other New World nations, slave populations were maintained by continuous importation from Africa. In the American South, however, the slave population grew through natural increase--that is, slave mothers had children who also became slaves. As a result, the vast majority of African Americans in slavery in the United States after 1810 were not African captives but native-born Americans, some of whose ancestors had been in this country nearly as long as the oldest white families. Slaves were denied even their original African names and made to accept whatever names their master imposed upon them. Masters had to evolve a system of rewards and punishments to maintain control over their more numerous slaves. As in any brutal system of unpaid labor, punishment was used more often than reward. As historian Kenneth Stampp has written, the slave owners strategy in handling their slaves was "to make them stand in fear!" A plantation, however, was not an extermination camp; it was a profit-making enterprise, and blacks had to be given certain rights and privileges to maximize their productivity. They were also valuable pieces of "property." To abuse them too harshly would diminish their value.

EDUCATION Slaves were legally denied the foundation of European education--the knowledge to read and write. Nonetheless, thousands of slaves acquired those skills, usually through voluntary or unintentional help from their young masters and mistresses as they were learning their lessons.

Slave Marriages

Most slave-owners encouraged their slaves to marry. It was believed that married men was less likely to be rebellious or to run away. Some masters favoured marriage for religious reasons and it was in the interests of plantation owners for women to have children. Child-bearing started around the age of thirteen, and by twenty the women slaves would be expected to have four or five children. To encourage childbearing some plantation owners promised women slaves their freedom after they had produced fifteen children. Several slaves recorded in their autobiographies that they were reluctant to marry women from the same plantation.

As John Anderson explained: "I did not want to marry a girl belonging to my own place, because I knew I could not bear to see her ill-treated." A study of slave records by the Freedmen's Bureau of 2,888 slave marriages in Mississippi (1,225), Tennessee (1,123) and Louisiana (540), revealed that over 32 per cent of marriages were dissolved by masters as a result of slaves being sold away from the family home.

FEMALE EDUCATION

Formal education for girls historically has been secondary to that for boys. In colonial America girls learned to read and write at dame schools. They could attend the master's schools for boys when there was room, usually during the summer when most of the boys were working. By the end of the 19th century, however, the number of women students had increased greatly. Higher education particularly was broadened by the rise of women's colleges and the admission of women to regular colleges and universities. In 1870 an estimated one fifth of resident college and university students were women.

THE LEGAL STATUS OF WOMEN During the early history of the United States, a man virtually owned his wife and children as he did his material possessions. If a poor man chose to send his children to the poorhouse, the mother was legally defenseless to object. Some communities, however, modified the common law to allow women to act as lawyers in the courts, to sue for property, and to own property in their own names if their husbands agreed.

Equity law, which developed in England, emphasized the principle of equal rights rather than tradition. Equity law had a liberalizing effect upon the legal rights of women in the United States. For instance, a woman could sue her husband. Mississippi in 1839, followed by New York in 1848 and Massachusetts in 1854, passed laws allowing married women to own property separate from their husbands. In divorce law, however, generally the divorced husband kept legal control of both children and property.

Conclusions: ……………………………………………………………

2. Consider the Identities from the Torn in Two exhibition (people), in particular Becky Robbins, Rebecca Parrish, James Harrison, Thomas Williams. Each of you chooses an identity.

Answer these questions that would have been pertinent to an antebellum audience: a.Would you return a runaway slave? b.. Did you vote for Lincoln? c. Would you have voted for secession?

Conclusions:…………………………

3. Look at the Slave Owner chart with your Students. Who was actually making the choices in the United States South during the antebellum period? What did freedom mean? Under what circumstances do people have control over their lives? The lives of others? When is it OK to break the rules? The law?

Slave Owner Chart (based on 1850 census data)

Number of Slaves Owned Number of Slave Owners 1 68,820

between 1‐5 105, 683

between 5‐10 80, 765

between 10‐20 54,595

between 20‐50 29,733 between 50‐100 6,196

between 100‐200 1,479

between 200-300 187

between 300-500 56

between 500-1000 9

more than 1000 2 Lesson 4: Arguments for and against slavery

To modern sensibilities, slavery in the antebellum period is more than harsh. It is almost inconceivable that so many Americans supported this brutal system of forced labor. Close inspection reveals how few contemporaries believed that it should be abolished outright.

1. Begin with a discussion about property rights. How are they protected by law now? Under what conditions does the government have the right to take an individual’s property? What is the meaning of “Eminent Domain”?

2. Now discuss the antebellum period and slavery. As harsh as it may be to hear, slaves were property and to many Americans during those years, that was not a subject of debate, except to confirm that it was wrong to take someone’s property.

There were of course those who believed that slavery was a moral outrage. Read excerpts from Douglass and

Howe (Frederick Douglass, “A Few Facts and Personal Observations of Slavery”: An Address

Delivered in Ayr, Scotland on March 24, 1846 http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/douglass/support7.html )and complete the Student Sheet.

Student Sheet

Read Federick Douglass’ speech (1846) and answer the following questions:

1.How does Douglass describe slavery? 3.What happened to his family? 4.How did he learn to read and write? 5.Why was learning to read both dangerous and crucial? 6. How does he describe his job as a free worker in New Bedford? 7. How are abolitionists presented? 7. How does he invoke religion in his message? 8. Do you think this was an effective strategy at that time? Why or why not? 9. 2.How does he make his individual story a criticism of the entire slave system?

FROM Ayr (Scot.) Advertiser, 26 March 1846. Reprinted in John Blassingame et al., eds., The Frederick Douglass Papers: Series One—Speeches, Debates, and Interviews, vol. 1 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), p. 195.

I am here to-night to let you know the wrongs, the miseries, and the stripes of three millions of human beings for whom the Saviour died and though time would fail me to give all the details of the horrid system by which they are held, I yet hope to place before you sufficient acts to enlist your sympathies in their behalf. Having last night directed attention to the relations of master and slave, and to the perversion of Christianity by the slave-holders, I now wish to state a few facts which have come under my own experience.

I was born a slave. My master's name is Thomas Auld. Besides me, he had other relations of our family whom he counted as his own property, and at this moment I have four sisters and one brother in the same state of degradation and bondage from which I myself have happily escaped. I have a grandmother who has reared twelve children, all of whom have been driven to the Southern slave market and sold; and now she is left desolate and forlorn, groping her way in the dark, without one to give her a cup of water in her declining moments. Thus does slavery break asunder the parental and domestic ties; the mother is separated from her children—the husband from the wife—and the brother from the sister; while all are driven about, like beasts of burden, at the will of their oppressors. And yet among this class are to be found individuals of the most exalted virtue—true and honourable to each other, while uniting in hatred of those who call themselves their masters, and sometimes even living as man and wife,—joined no doubt by Him whose tie no one can break asunder, though unacknowledged by their heartless taskmasters.

I owe my liberty and my learning all to stealth ; and, in order to give you some idea of the manner in which I learned to read, I must communicate a little of my history. When seven years old, I was sent by my master to his son- in-law's, and there had the fortune to find a kind and tender-hearted mistress. She was newly married, and her family never having kept slaves, I was treated by her with great lenity. She taught me my letters, and continued to instruct me till she learned that by so doing she was breaking the laws—for in America the crime of teaching a slave is punishable, in some parts, with death for the second offence. Her husband found out what she had been engaged in, and stopped her, at the same time saying that this was the very way to render slaves unmanageable,—which is indeed the true philosophy of all slaveholding. She did stop, but my master's words sunk into my heart, young as I was, and the opposition thus given to my progress only incited me the more in the pursuit of education. I obtained a primer— applied to boys on the street, when sent on messages, to instruct me,—stealthily embraced every opportunity of advancement, till in four years I could in some measure read the Scriptures, and many a time have these hands (holding them up) lifted from the street the soiled and waste leaf, cleaned and dried it, and then pored over it till I had mastered its contents.

When somewhat grown up, I was put into the ship-yard to pick oakum, boil pitch, and otherwise assist the carpenters. Here I learned the first rudiments of writing, by observing the marks which the workmen made on the wood, when fitting it for any particular part of the ship.. Many a time have the children in the street taken the chalk from me, with the contemptuous sneer, "can a nigger write?" and displayed their superior powers, gratifying at once their own vanity and my most earnest wishes. About this time I fell in with some old copy books of my young master, and by writing on the spaces betwixt the lines, soon rendered myself pretty expert at penmanship. By similar means I acquired a knowledge of figures, and learned the multiplication table, Thus persevering, I at length acquired, unknown to my master, a considerable knowledge of the English language, writing, and arithmetic, and it was just as he said, for the more learning and information I picked up, the more did I become convinced that I was held unjustly in slavery.

I looked on my cruel taskmasters with the utmost horror, and shuddered at the very presence of men who had robbed me of father, mother, and friends,—who had stripped me of every right which God had given to me—and who would, if they had been able, have crushed every aspiration after freedom in my bosom. I determined to be free, and from the age of ten years, was continually planning means to snap my chain; but it was not till I was twenty years old that I succeeded in what I had long toiled for. The means of my escape I have never revealed, lest I should disclose to the cruel slaveholder what may be of use to his victims.

After my escape, I arrived at New Bedford, where I was engaged rolling oil casks on the quay, and doing anything that presented itself; yes, ladies and gentlemen, you must know that the individual who now addresses you even occupied at that time the elevated position of a chimney-sweep. (Cheers and laughter.) I must say that I worked harder then than when in slavery; but the work was pleasant, for I had an end to serve by it. I had not the mortification of seeing my wages taken by a cruel master, and spent in luxuries by him and his friends. No; I wrought for myself—I wrought for my wife, and I was contented and happy. Mr. Douglass proceeded to state the circumstances which had first led to his appearance in public. He had been requested to address an abolitionist meeting by an individual who had heard him officiate in a Methodist class, and he thus described his sensations in appearing before an audience of white men:—"I was called on to tell what I had suffered, and what I thought and knew of slavery. I hesitated—I trembled. Accustomed to consider white men as my bitterest enemies, I dared not for some time look them in the face. I found, however, what I had never seen before, that the countenances of the audience were illumined with kindness—that I was indeed among a band of brothers— and so I proceeded to tell my simple tale. It had the desired effect. The woes of slavery coming from one who had seen them—who had felt them, created an impression on the meeting which was productive of great good."

From that time he was taken under the auspices of the Abolitionist Society, and his humble labours had been blessed in the cause of his fellows. He had awakened an influence which was every day increasing, and swelling the tide which he hoped would soon beat down the prison walls of slavery. He had always, when lecturing, concealed the name of his master, and likewise changed his own, and at the same time withheld all the details of his escape, and where he had been born, suspicions were raised by the slaveholders, who were very much disturbed by his appearance in public, that he was an impostor. To counteract this he at length resolved to write his life, which he accordingly did, but this only exposed him still more to the rage of his persecutors.

Mr. Douglass at length felt that it was no longer safe to remain in America; he accordingly crossed the Atlantic.

Mr. Douglass proceeded to give some details of slavery in connection with Christianity. He said—"My master was a class-leader in a Methodist Chapel, and considered in every way, according to the standard of the place, an exemplary and pious man; yet I have seen the monster come home from his meeting, tie up my own cousin, and with his own hands apply the whip to her bare back till the warm red blood was dripping to her heels, and at the same time quoting the Scripture passage—'He that knoweth his master's will, and doeth it not, shall be beaten with many stripes!' It is quite customary to brand slaves, as the people in this country mark their cattle, but by a process the most cruel and agonising. The arm of the slave is stripped, or whatever part the instrument is to be applied to, and the branding iron, almost red hot, broils the name of the master into the quivering flesh of the wretched victim, causing the most excruciating agony. I have seen all this done by men calling themselves Christians; and not only this, but deeds of darkness too revolting to be told, and from which humanity would shudder.

Thousands are thus bored and beaten, and all done under the sanction of the majesty of LAW, and in a country, too, which boasts of her liberty! About five years ago," Mr. Douglass continued, "it was discovered that slavery had her stronghold in the church,—that under the very droppings of the sanctuary the chains and fetters of the slaves were forged, and that indeed Christianity had become so linked with slavery, that it was time for some great effort to be made to remedy the awful state of affairs. An effort was made. The churches in the northern states stood out against the accursed system, and declared that they could no longer hold fellowship with slave-tolerating bodies. Public opinion became arrayed on his side.

He said it was not against the Free Church as a Church he aimed his arguments—his prepossessions were in her favour—but against her alliance with the curse of slavery. The only remedy for the evil was to send back the money, an exclamation which he vehemently repeated time after time. He concluded by calling on the members of the Free Church to exert their influence in the cause of the poor slave.

Mr. Douglass took his seat amid prolonged applause.

Choose a speaker and report to the class

------

STEP 2: CLASS DISCUSSION

Choose an identity from the enclosed “ Torn in two exhibition – Identies” and be ready to sustain a discussion on this topic:

Was it worth fighting the civil War?

Support your opinion with ideas consistent with your identity.