"Comparatives" in English and Japanese Emi Mukai (09/27/05) HH’s comments on sections 1, 2 and 4.

1. Introduction The sentences in (0) can be translated into (0), and t and thus they have been widely regarded as ""comparatives" in Japanese which are parallel to (0) and yori is analyzed as the Japanese counterpart of than; see . (Kikuchi 1987, 2002, Ishii 1991, 1999 among others); especially in these analyses, yori is analyzed as the counterpart of than.

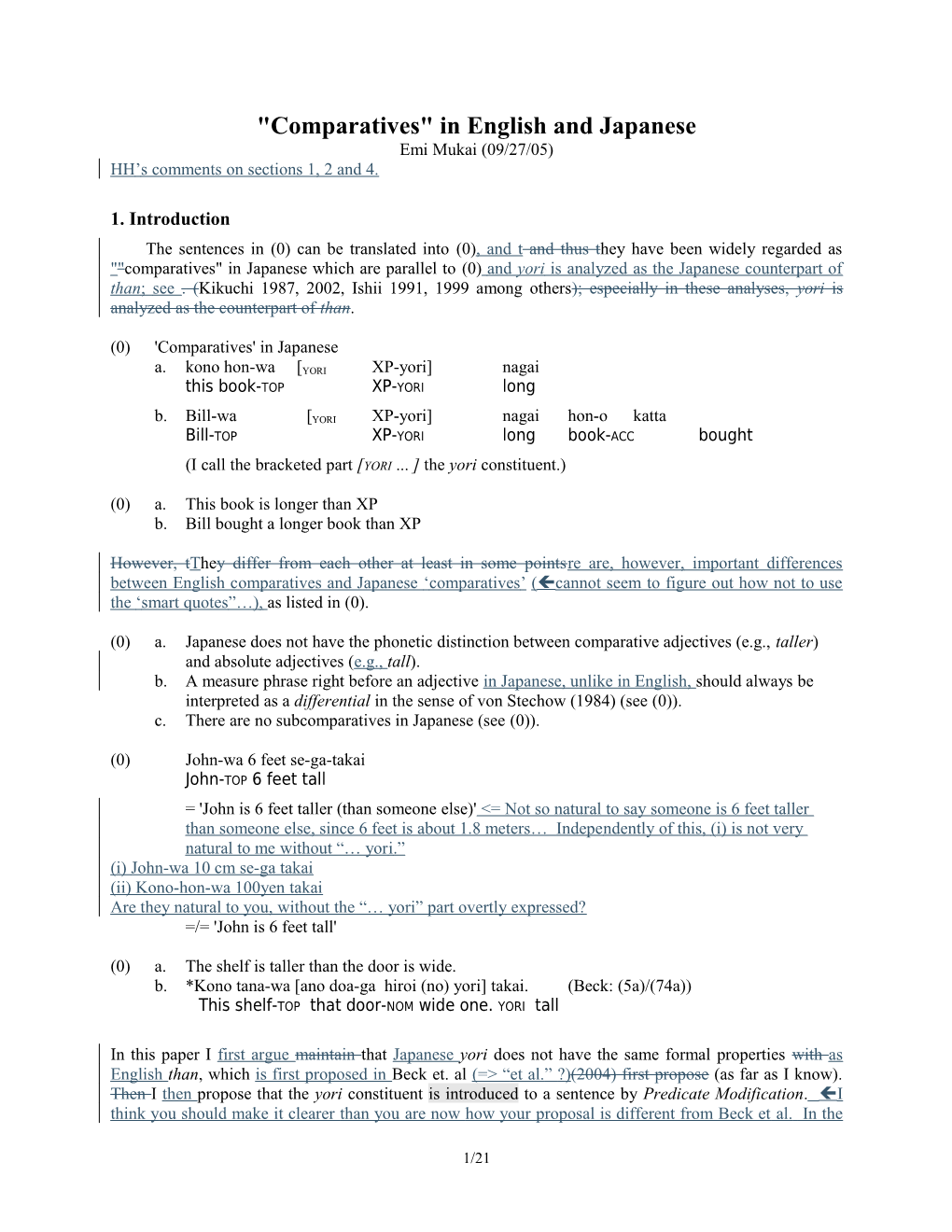

(0) 'Comparatives' in Japanese

a. kono hon-wa [YORI XP-yori] nagai this book-TOP XP-YORI long

b. Bill-wa [YORI XP-yori] nagai hon-o katta Bill-TOP XP-YORI long book-ACC bought

(I call the bracketed part [YORI ... ] the yori constituent.)

(0) a. This book is longer than XP b. Bill bought a longer book than XP

However, tThey differ from each other at least in some pointsre are, however, important differences between English comparatives and Japanese ‘comparatives’ (cannot seem to figure out how not to use the ‘smart quotes”…), as listed in (0).

(0) a. Japanese does not have the phonetic distinction between comparative adjectives (e.g., taller) and absolute adjectives (e.g., tall). b. A measure phrase right before an adjective in Japanese, unlike in English, should always be interpreted as a differential in the sense of von Stechow (1984) (see (0)). c. There are no subcomparatives in Japanese (see (0)).

(0) John-wa 6 feet se-ga-takai John-TOP 6 feet tall = 'John is 6 feet taller (than someone else)' <= Not so natural to say someone is 6 feet taller than someone else, since 6 feet is about 1.8 meters… Independently of this, (i) is not very natural to me without “… yori.” (i) John-wa 10 cm se-ga takai (ii) Kono-hon-wa 100yen takai Are they natural to you, without the “… yori” part overtly expressed? =/= 'John is 6 feet tall'

(0) a. The shelf is taller than the door is wide. b. *Kono tana-wa [ano doa-ga hiroi (no) yori] takai. (Beck: (5a)/(74a)) This shelf-TOP that door-NOM wide one. YORI tall

In this paper I first argue maintain that Japanese yori does not have the same formal properties with as English than, which is first proposed in Beck et. al (=> “et al.” ?)(2004) first propose (as far as I know). Then I then propose that the yori constituent is introduced to a sentence by Predicate Modification. I think you should make it clearer than you are now how your proposal is different from Beck et al. In the

1/21 final version of the paper, more should be included than this at the end of section 1.

2. Previous analyses ---English 2.1. The standard analysis of English comparatives (Bresnan 1973; von Stechow 1984; Heim 2000 among others)

Let us first briefly review the standard analysis of English comparativesbriefly. First of all, it has been widely analyzed agreed that an adjectives are is a two-place predicate and; they it are is a functions from a degrees to the a set of individuals (

(0) [[Adjective]] = d. x. x is Adjective to d (e.g., [[tall]] = d. x. x is tall to d)

Adjectives then take DegPs as their first argument; i.e., [the combination of them <= Is this okay?] is done through Functional Application.

(0) Functional Application (FA) (Heim & Kratzer 1998: 44: (3)) If is a branching node, {, } is the set of 's daughters, and [[]] is a function whose domain contains [[]], then [[]] = [[]]([[]]).

Under the analysis, whether adjectives are realized as comparative (taller) or as absolute (tall) depends on what the first argument of the adjectives, DegP, are is like. In the case of the former, the DegP is headed by the degree morpheme (er/more/less etc.). In the latter case, the DegP is POS ( Indicate what “POS” stands for. “positive”?) operator (see (0)).

(0) 3 John e 3 is AP

POS

(0) [[POS]] = P

The semantics of degree morpheme er is as in (0a), which contains the maximality operator in (0b).

(0) a. [[er]] = D'

max: = D

In addition to (0a), the degree morpheme er has the second semantic specification as shown in (0) tooas

1 Hackl (2000: 49) cites von Stechow (1984), Rullmann (1995), Heim (2000), and Schwarzschild & Wilkinson (200x) for the assumption that a maximality operator is "part of the meaning of the comparative operator." (Ibid.)

2/21 well, which is used when comparative adjectives are followed by a differential.

(0) [[er]] = D'

The than clause involves the degree abstraction at LF, and the whole than clause undergoes extraction at PF. In sum, the sentences in (0) are analyzed as in (0), (0), (0) and (0), respectively, under the standard analysis.

(0) a. John is tall. b. John is 6 feet tall. c. John is taller than Bill is. d. John is 1 inch taller than Bill is.

(0) John is tall (=(0a)) a. Before Spell-Out & PF b. LF 3 3 John e 3 POS

POS1

t1 d

c. [[John is POS tall]] = [[POS]] ([[1]] ([[John is t1 tall]]) ) = P. d[P(d)=1 and d>ds] (d1. John is d1-tall) = d[d. John is d-tall (d)=1 and d>ds] =d[John is d-tall and d>ds] (where ds is the standard degree which is contextually identified.) d. John is tall is true iff there exists the unique d such that John is d-tall and d exceeds the

standard degree ds.

(0) John is 6 feet tall (=(0b)) a. Before Spell-Out & PF & LF 3 John e 3 is AP 3 DegP tall

b. [[John is 6 feet tall]] = [[tall]] ([[6 feet]]) ([[John]]) = d. x. x is d-tall (6 feet) (John) = John is 6 feet tall c. John is 6 feet tall is true iff John is tall to 6 feet.

3/21 (0) John is taller than Bill is (=(0c)) a. Before Spell-Out b. PF 3 3 CP/PP John e 3 John e 3 6 is AP is AP than Bill is 3 3

c. LF

3

than Op1 Bill is t1-tall 3 DegP tall

t2 d

d. [[John is taller than Bill is]]= [[er]] ([[than Op1 Bill is t1 tall]]) ([[2](John is t2 tall]])) = [[er]] (d1. Bill is d1-tall) (d2. John is d2-tall) = max(d2. John is d2-tall) > max(d1. Bill is d1-tall) e. John is taller than Bill is is true iff the degree d2 such that John is d2-tall exceeds the degree d1 such that Bill is tall.

Now, without (what corresponds to er) in JP, and if there is nothing in Japanese that introduces the maximality operator, we never get anything like the third line of (0d), with the maximality operator? Well, a more basic question should be: do we ever get type

(i) a. Do we have something of type d and/or of type

(0) John is 1 inch taller than Bill is (=(0d))

4/21 a. Before Spell-Out b. PF 3 3 CP/PP John e 3 John e 3 6 is AP is AP than Bill is 3 3

c. LF

3

than Op1 Bill is t1 tall 3 DegP tall

t2 d

d. [[John is 1 inch taller than Bill is]]

= [[er]] ([[than Op1 Bill is t1 tall]]) ([[1 inch]]) ([[2](John is d2-tall]]) ) = [[er]] (d1. Bill is d1-tall) (1 inch) (d2. John is d2-tall) = max(d2. John is d2-tall) max(d1. Bill is d1-tall) = 1 inch e. John is 1 inch taller than Bill is is true iff the degree d2 such that John is d2-tall minus the degree d1 such that Bill is d1-tall equal 1 inch.

2.2. Type-shifting operation for a measure phrase (Hackl 2000)

The than phrase sometimes contains a measure phrase alone, as in (0).

(0) John is taller than 6 feet.

For such a type Hackl (2000) proposes "a type shifting operation similar to Partee's (1987) BE operation which maps an individual to its corresponding singleton." (Hackl 2000: 50) In short, "there are two interpretations of measure phrases as given in [(0)]." (Ibid)

(0) (=Hackl 2000: chap. 1, (65)) a. [[six feet]] = 6'

b. [[six feetBE]] = d. Dd. d = 6'

With the this assumption, the sentence in (0) is combined in the way as indicated in (0a). (0b) is its truth condition.

5/21 (0) a. [[John is taller than 6 feet]]

= [[er]] ([[than 6 feet]]) ([[i]]([[John is ti tall]]) = [[er]] (d. d=6') (di. John is di-tall) = max(di. John is di-tall) > max(d. d=6') = the unique d1 such that John is d1-tall > the unique d2 such that d2=6' b. John is taller than 6 feet is true iff the degree d1 such that John is d1-tall exceeds 6 feet.

While the investigation of the validity of the claim above is not in the scope of my paper, it seems to be the case that the second interpretation of a measure phrase (=(0b)) is needed (though it is not explicitly mentioned in Hackl (2000)) when we think of consider a sentence with a measure phrase being as a predicate (see as in (0a)).

(0) a. John's height is 6 feet. b. [[John's height is 6 feet]] = [[6 feet]]([[John's height]]) = d. d=6' (John's height) = John's height = 6' Well, actually to account for (i), under the general approach adopted here, you will have to say something extra, to begin with, I suppose.

(i) John is 6 feet.

As in (0b), John's height is 6 feet is true iff the degree expressing John's height is a member of the set of being 6 feet.

3. Various analyses for Japanese yori constructions 3.1. Analysis 1

---Following the standard analysis. ---Treating the yori constituent as parallel to the than clause. (Kikuchi 1987, 2002, Ishii 1991, 1999, Nakanishi 2004). ---The soundless er is assumed.

Problem for analysis 1 --- (0b) and (0c) are left unsolved. (0) b. A measure phrase right before an adjective should always be interpreted as a differential (see (0)) c. There are no subcomparatives in Japanese (see (0)).

3.2. Analysis 2 (Analysis 1 + Schwarzschild (to appear))

Schwarzschild's idea: The measure phrase before an adjective should be interpreted as a differential as a default.

(0) John-wa 6 feet se-ga-takai John-TOP 6 feet tall = 'John is 6 feet taller (than someone else)' =/= 'John is 6 feet tall'

6/21 Problem for analysis 2 --- (0c) is still problematic.

3.3. Analysis 3 (Kikuchi 2002)

3-1 Absolute adjectives (regardless of with or without a measure phrase (i.e., tall in John is (6 feet) tall)) are different from comparative adjectives (taller). 3-2 Japanese only has comparative adjectives.

Problem for analysis 3 --- (0c) is still left unsolved.

3.4. Analysis 4: Treating the yori constituent as parallel to compared to in English (Beck et. al (2004))

4-1 The yori constituent is not the counterpart of the than clause. Rather, it is parallel to compared to.

(0) a. Compared to XP, this book is {long/longer}. b. Compared to XP, John bought a {long/longer} book.

4-2 Adjectives can still be of type

4-3 The combination between the yori constituent and the rest of the sentence are done in Pragmatics.

4-4 The compliment of yori should always be individuals. The yori constituent in (0c) is corresponding to free relatives such as 'what Bill bought', though it appears to be an IP on the surface.

(0) a. John-wa [YORI ano hon-yori] nagai hon-o katta John-TOP that book-YORI long book-ACC bought

b. John-wa [YORI Bill-ga katta no-yori] nagai hon-o katta John-TOP Bill-NOM bought one-YORI long book-ACC bought

c. John-wa [YORI Bill-ga katta-yori] nagai hon-o katta John-TOP Bill-NOM bought-YORI long book-ACC bought

Japanese subcomparatives such as in (0b) are unacceptable since it is difficult to nominalize the complement of yori in these cases. Since than can take IP as its complement, any sentence containing the than clause in (0a) can be acceptable even if the IP cannot be nominalized as in (0).

(0) a. The shelf is taller than [the door is wide]. b. *Kono tana-wa [ano doa-ga hiroi (no) yori] takai. (Beck: (5a)/(74a)) This shelf-TOP that door-NOM wide one. YORI tall

(0) *the one that the door is wide

Problems for analysis 4 1. (0b) is unsolved. 2. (The combination of this analysis and Schwarzschild (to appear) might seem perfect, but...) It is quite unclear how the yori constituent and the rest of the sentence are combined in the

7/21 syntactic and semantic structures under the analysis. 3. The nominalized version of (0b) is still unacceptable.

(0) *Kono tana-wa [ano doa-no hirosa yori] takai This shelf-TOP that door-GEN width YORI tall 'This shelf is taller than the width of that shelf.'

4. Proposals 4.1. English than clauses

I propose that there is only one type of Adjectives, which is of type

(0) [[Adjective]] = x. x is Adjective

[The meaning of gradability comes from functional category #. It takes an adjective as its first argument and the combination of # and an adjective is of type

(0)

The functional category # then takes Degree phrase (DegP) as its second argument (in its specifier position). This idea is also suggested in the lecture by Roumi Pancheva (Spring 2005).

(0) #P (cf. Roumi Pancheva lecture note 5, (11)) 3 DegP 3 # A

I simply follow the standard analysis as for in regard to the rest of the assumption without any further discussion. Therefore, the only difference between the analysis proposed here and the standard analysis is that [the gradable meaning is introduced by # in the former while it is part of the meaning of adjectives from the beginning in the latter <= Redo.]. [John is tall is ambiguous in my analysis; one has the meaning of the comparison with the standard degree (=(0a)), and the other has the meaning of John's having the properties of tallness (=(0b)). <= State or maybe repeat? how this is different from the standard analysis. You can, for example, refer to the standard analysis of (0a) introduced above.

(0) a. 2 b. 2 John 2 John 2 is 2 is tall POS 2 # tall

4.2. Japanese yori constructions

8/21 A general question: We have sentences like (i).

(i) John-wa Bill-to kuraberuto/kurabete ookii.

What semantics would you give to sentences like this? It seems, at least at first sight, that the meaning of (i) is very close to, if not identical to, that of (ii).

(ii) John-wa Bill-yori ookii.

This can be taken as (indirect) support for the proposal made in Beck et al. re. Japanese. What about English? I wonder if (iii) and (iv) mean the same thing in the same way (i) and (ii) seem to.

(iii) John is big, {if we compare him to Bill/comparing him to Bill/compared to Bill}. (iv) John is bigger than Bill.

Now consider (v).

(v) a. John sings more beautifully than Bill. b. John sings beautifully, if we compare him to Bill.

It seems that (v-a) clearly compared two degrees, the degrees to which J and B sing beautifully. In contrast, (v-b) does not seem to express such comparison of two degrees. What (v-b) expresses seems to be like (vi) instead.

(vi) If we take Bill as the standard cut-off point, the manner in which John sings can be categorized as 'beautifully'.

So, in (v-b), Bill is serving as (the individual who provides) the standard degree that the POS operator refers to.

Now consider (vii).

(vii) a. John-wa Bill-to {kuraberuto/kurabete} zyoozuni (uta-o) utau. b. John-wa Bill-yori zyoozuni (uta-o) utau.

Although I was not able to tell any clear meaning difference between (i) and (ii), I seem to detect some difference between (vii-a) and (vii-b). (vii-b) clearly has the sense of comparison, which we can suppose comes from the semantics of 'yori'. (vii-a), on the other hand, is more like (vi), especially with " kuraberuto." (I am not so sure about the "kurabete" version. But maybe it is the same as the other version…)

So, after all, the JP 'comparatives' do compare things, it seems, unlike what I understand Beck et al. argue.

One might think that the assumption of # above is trivial. However, it becomes important when we think of consider (or turn to) yori constructions in Japanese/. I propose that Japanese does not have the functional category #, with adopting the thesis in (0), which is first pursued by Fukui 1986 (and Kuroda 1988 in effect), and adopted in works such as Ueyama 1998 and Hoji 2003.

(0) There are no 'active functional categories' in Japanese (in the terms of Fukui 1986).

9/21 I guess you may need to say something to explain to the reader what is meant by ‘active (as opposed to inactive) functional categories’… It then follows that we do not have the combination of # and Adjective in Japanese (i.e., a constituent of type

(0) The properties of the yori constituent (i.e., “… yori”) a. The Its head of it is yori, which is of type

(0) [[YORI]] = y. x. x {is (different) from/exceeds} y.

(0) PP

[The other => Another?] difference diversity between Beck et. al's (2004) analysis and mine comes to the surface emerges when we think of consider the first argument of yori more deeplyclosely. on the one hand, mMy proposal is that the constituent before yori in (0b) is not restricted to a relative clause [but it can be allowed if only it is a complex NP, and that the IP-like constituent in (0c) involves the ellipsis of the head noun no, which is called a functional noun, and the entire constituent is again a complex NP <= Redo.].2 That is, the constituent in (0b) and that in (0c) are exactly the same with each other except for the PF omission deletion of no in the case of (0c). On the other hand, Beck et. aAl., on the other hand, propose that the constituent before yori in the case of (0b) is always a relative clause headed by the functional noun no which is parallel to the one in English, as shown in (0), and that the apparent IP constituent right before yori in (0c) is an individual with the form of free relatives as in (0). As presented now, the difference between the two analyses is not given as clearly as it should.

2 What I call a relative clause contains an empty pronoun interpreted as equal to the head noun of the clause, while the head noun of what I call a complex NP and an empty pronoun inside xxx (if any) does not have to be interpreted as equal. In this sense, the former is defined as one type a sub-case of the latter. (Though I am not sure that this way of calling them is the standard way or not, I use those terms in this paper.) <= Google-search under “pure complex NP.” You may get something about how the terms have been used in the literature. Fukui in his paper in the late 1980s called (i) a pure complex NP, distinguishing it from (ii) (which he called a relative clause construction or something). (i) John-ga kita koto (ii) John-ga kaita hon Don’t remember whether he called (iii) an instance the former. (iii) sakana-ga yakeru nioi

10/21 (0) a. [[John-ga kaita] no yori] John-NOM wrote f.n. YORI

b. [[[John-ga kaita]] no] => [[Opi [John-ga ei kaita]] no] c. THEC(x. ronbun (x) & John wrote x) <=relative clause (Cf. Beck: (47a), (52) & (53))

(0) a. [[John-ga kaita] yori] John-NOM wrote YORI

b. [John-ga kaita] => [Opi [John-ga ei kaita]] c. max(x. John wrote x) <=free relative (Cf. Beck: (34) & (72))

Beck et. al's analysis may be compatible with the fact that we can indeed have a relative clause right before yori as shown in (0).

(0) Mary-wa [[[John-ga ec kaita] ronbun] yori] nagai ronbun-o kaita (Beck: (45b)) Mary-top John-nom wrote paper YORI long paper-acc wrote 'Compared to the paper that John wrote, Mary wrote a long paper.' (Intended reading) 'Mary wrote a longer paper than the paper that John wrote.'

However, as has been pointed out already in Kikuchi 1987, Ishii 1991 and Ueyama 2004 (and probably others as well), the empty element inside the constituent before yori is not always be equal to the noun before yori.

(0) a. ... [[[Mary-ga ec kaita] peeji suu] yori] ... Mary-NOM wrote page number YORI (Intended meaning) ' ... than the amount number of the pages such that Mary wrote something ...' b. *Mary-ga peeji suu-o kaita Mary-NOM page number-ACC wrote

If we followed Beck et. al and assumed (i) that no were is always the head of a relative clause in the case like (0b) and (ii) that there were is always a soundless head noun corresponding to a head of a free relative in the case like (0c), then it would be mysterious why the sentence in (0b) is not acceptable. Now let us go into the issue how the yori constituent is combined with the rest of the sentence. I propose that the yori constituent is an adjunct adjoininedg to AP, and the gradable meaning is the consequence of Predicate Modification between the AP and the yori constituent. I need to ask you about (0)… (0) Predicate Modification (PM) (=Heim & Kratzer 1998: 65, (6))

If is a branching node, {, } is the set of 's daughters, and [[]] and [[]] are both in D

[[]] = x De. [[]](x) = [[]](x) = 1

The sentence in (0a), for example, has the structure in (0b) and the meaning is computed in Semantics as shown in (0c) under the analysis being pursued here.

(0) a. kono hon-wa [YORI LGB-yori] nagai this book-TOP LGB-YORI long (Intended meaning) 'This book is longer than LGB.'

11/21 b. IP t 3 NP e I' | 3 kono hon-wa AP

c. [[LGB yori nagai]] ([[kono hon]]) LGB YORI long this book

= x De. [y. y is long](x) & y. y exceeds LGB](x)(this book)

= x De. [x is long & x exceeds LGB](this book) = this book is long & this book exceeds LGB.3

That is, Japanese sentences do not have the comparative meaning unless they have the yori constituent. <= What would you say about (i)? (i) Kono hon-wa motto nagai. Would you say that (i) contains a phonologically null “… yori” phrase? (0) a. Kono hon-wa nagai This book-TOP long 'This book is long.' b. [[nagai]] ([[kono hon]]) = x. x is long (this book) = this book is long (=this book has the property of being long.)

We have seen the cases of 'comparative adjectives as a predicate' so far. The same lines of analysis go to the cases of 'comparative attributive adjectives' in (0).

(0) a. John bought a more expensive book than Bill did. b. John-wa Bill-ga katta yori takai hon-o katta John-TOP Bill-NOM bought YORI expensive book-ACC bought (Intended meaning) 'John bought a more expensive book than Bill bought.'

[(0a) is analyzed as parallel to (0a) under the previous analyses. <= Why do you start discussing (0) and (0) before you have even introduced them?] However, they have the meaning difference as shown in (0d) and (0f) under the analysis pursued here.

(0) a. John bought a more expensive book than Bill did.

3 Strictly speaking, this is not (quite?) the interpretation of what Japanese native speakers get from the sentence in (0a) (the same remark goes to (0f)). We will come back return to this issue in section 4.3.

12/21 b. LF IP 3 DegP 3 | 1 3 | John e 3 more than Bill did I VP

t1 # AP

c. [[IP]] = [[more]] ([[than Bill did]]) ([[1]]([[John bought a t1 expensive book]]) = [[more]] (d2. Bill bought a d2-expensive book)(d1. John bought a d1-expensive book) = max(d1.John bought a d1-expensive book) > max(d2.Bill bought a d2-expensive book) d. John bought a more expensive book than Bill did is true iff the degree d1 such that John bought a d1-expensive book exceeds the degree d2 such that Bill bought a d2-expensive book.

(0) a. John-wa Bill-ga katta yori takai hon-o katta John-TOP Bill-NOM bought YORI expensive book-ACC bought (Intended meaning) 'John bought a more expensive book than Bill bought.'

b. LF IP 3 John-wa 3 John-top VP I 3 | NP3 V ta 3 | [+past] AP2 NP2 kat 3 | buy PP AP1 hon-o 3 | book-acc NP1 P takai 6 | expensive Bill-ga katta (no) yori Bill-NOM bought one YORI

c. [[AP2]] = x De. [[PP]](x) = [[AP1]](x) = 1 (by PM) = x exceeds the one that Bill bought & x is expensive d. [[NP3]] = [[AP2]](x) = [[NP2]](x) = 1 (by PM) = x exceeds the one that Bill bought & x is expensive & x is a book

13/21 e. -closure to NP3 =>[[NP3]] = x. [x exceeds the one that Bill bought & x is expensive & x is a book] f. [[IP]] = John bought x. [x exceeds the one that Bill bought & x is expensive & x is a book]4

4.3. The meaning of yori and the distinction between type e and type d

Let us look into the meaning of the yori constituent more in detail. Consider the sentence in (0).

(0) Bill-wa John-yori se-ga takai Bill-TOP John-YOR tall (Intended meaning) 'Bill is taller than John.'

Under the analysis pursued abovehere, the sentence has the structure in (0) both before Spell-Out and at LF, with the lexical specifications of tall takai ‘tall’ and YORI in (0). Recall that the yori constituent adjoins to the AP and they are combined through PM in Semantics.

(0) IP t 3

(0) a. [[tall]] = x. x is tall (See (0).) b. [[YORI]] = y. x. x {is (different) from/exceeds} y.

Though yori does not appear in our daily speech as much as kara 'from' nowadays, that yori is of a category P with the meaning from is motivated by the fact that it is used in a formal situation such as in (0a), or in a literary (or archaic) language as in (0b), where it is interpreted as from and can be replaced by kara 'from'.

(0) a. kore-yori kaigi-o hajimemasu. this:time-YORI conference-ACC start (At the beginning of a formal business meeting) '(Lit.) We start the conference from now.' b. tomo ari. enpoo-yori kitaru. friend there:is far:away-YORI come 'There is a friend who comes from far away.'

The semantic composition for (0) is done as in (0).

(0) [[Bill-TOP John-YORI tall]] = [[tall]]([[Bill]]) = [[John-YORI]]([[Bill]]) = 1 (by PM) = x [x is tall] (Bill) & x [x exceeds John] (Bill) = Bill is tall & Bill exceeds John

4 See footnote Error: Reference source not found.

14/21 However, when we consider the meaning of the sentence more deeply, we realize that the meaning in (0) does not exactly express what Japanese native speakers get for the sentence in (0) (as I have mentioned in footnote Error: Reference source not found). The Its meaning for it should rather be as in (0).5

(0) 'Bill is tall & Bill's height exceeds John's height.'

In other words, it is likely to be the case that yori is of type

(0) a. Mary is taller than Bill b. Mary is taller than Bill is => max(d. Mary is d-tall) > max(d. Bill is d-tall)

Heim (1985), Lechner (1999, 2001), Hackl (2000) Kennedy (1997) all maintain that all phrasal comparatives have an underlying clause (the reduced clause analysis). (0a) is derived from (0) under the analysis.

(0) Mary is taller than [Opi [Bill is ti tall] ] (The highlighted part will be deleted at PF.)

I will not discuss the validity of the analysis here. Rather, my concern is whether the deletion of a degree expression is needed in the case of yori constructions in Japanese. Let me us put it in a more concrete way. As shown in (0), yori can follow either an individual (a, c, e) or a degree (b, d, e, f, g or h). (The functional noun no in (0e) can be interpreted either as an individual ('one' in English) or as a degree, while that in (0f) is always taken as a degree.) The question is whether (0a) and (0c) involve the deletion of (no) nagasa '('s) length' in Syntax, or there is no syntactic operation and the meaning of the length is provided in Pragmatics.

5 The arguments of the yori appearing in sentences like (0) are (or can be?) individuals, not degrees. The difference will be compatible with my proposal (which I will introduce in section 4.4.1) that there are two types of yori.

6 [It may be the case that the distinction between d and e is not crucial in English at all in the literature, if I judge from the way that Roumi suggested to me. <= Redo.]

15/21 (0) a. Barriers b. 200 peeji 200 pages c. Mary-ga kaita hon Mary-NOM wrote book d. Mary-ga kaita peeji suu Mary-NOM wrote page number LGB-wa e. Mary-ga kaita (no) yori nagai LGB-TOP Mary-NOM wrote f.n. YORI long f. kono hon-ga nagai (?no) this book-NOM long f.n. g. kono hon-ga nagai sono doai/teido this book-NOM long that degree h. kono hon-no nagasa this book-GEN length

We do not have(seem to) make any different negative predictions, but my hunch goes to the latter idea. More importantly, my analysis can only go with the latter idea; if we always have a deletion of no nagasa to get thea meaning of 'the length of X', then the subject of the sentence LGB should also be derived from LGB-no nagasa, or we would not get the meaning of 'the length of LGB exceeds the length of X'. However, the argument of an adjective should be individuals; that is, the subject of nagai is LGB, not the length of LGB. Then it is unclear how the subject can both be LGB and be LGB-no nagasa in Syntax at the same time. The issue seems related to how we treat what is called Unagi-bun. One might suspect that the problem I just mentioned would be everyone's problem just like the issue of how to treat the phrasal comparatives in English if we stick to the standard idea that yori is the counterpart of than and adjectives are of type

4.4. How the observations in (0) are explained 4.4.1. The lack of comparative-absolute distinction of adjectives in Japanese

The property in (0a) is simply because adjectives are always of type

(0) a. Japanese does not have the distinction between comparative adjectives (e.g., taller) and absolute adjectives (tall).

4.4.2. 'Differentials' in Japanese

Let us turn to (0b), which is repeated below.

(0) b. A measure phrase right before an adjective should always be interpreted as a differential (see (0)).

(0) John-wa 6 feet se-ga-takai

16/21 John-TOP 6 feet tall = 'John is 6 feet taller (than someone else)' =/= 'John is 6 feet tall'

If the current analysis is on the right track, the measure phrase in front of an adjective in Japanese (6 feet in the case of (0)) cannot be interpreted in the same way as with the interpretation of 6 feet in John is 6 feet tall, due to the lack of a constituent of type

(0) [[YORI]] = y.z.x. x exceeds y by z

My suggestion means that there are two kinds of yori in Japanese, one of which is of type

(0) a. kore-yori kaigi-o hajimemasu. this:time-YORI conference-ACC start (At the beginning of a formal business meeting) '(Lit.) We start the conference from now.' b. tomo ari. enpoo-yori kitaru. friend there:is far:away-YORI come 'There is a friend who comes from far away.'

The structure for the sentence in (0a) is as in (0b).

(0) a. Bill-wa John-yori 5cm se-ga-takai b. IP t 3 Bill-wa e 3 Bill-top AP

I propose that the structure before Spell-Out for the sentence in (0) is the one in (0b), and the yori constituent in (0) happens to be unpronounced. Incidentally, measure phrases can play a role as a predicate, as shown in (0).

(0) Bill-no se-no-takasa-wa 170cm da Bill-GEN height-TOP 170cm COPULA

17/21 (Intended meaning) 'Bill's height is 170cm.'

(As discussed/mentioned above?) For such a type, Hackl (2000) proposes "a type shifting operation similar to Partee's (1987) BE operation which maps an individual to its corresponding singleton." (Hackl 2000: 50) In short, "there are two interpretations of measure phrases as given in [(0)]." (Ibid)

(0) (=Hackl 2000: chap. 1, (65)) a. [[six feet]] = 6'

b. [[six feetBE]] = d. Dd. d = 6'

[One might suspect that my approach wrongly predict that the Japanese sentence and the English one in (0) can have the same meaning with each other, for the former could have the structure in (0) after the type shifting operation. <= Redo.]

(0) a. IP 3 John-wa3 e AP

b. [[John-wa 6 feet se-ga-takai]] = [[6 feet]](John) & [[se-ga-takai]](John) John is 6 feet & John is tall7

I propose that the effect of applying the type shifting operation to a measure phrase in Japanese comes from the meaning of copula da.

(0) a. [[da]] = y. x. x is y

In sum, ...

4.4.3. The lack of subcomparatives in Japanese

Beck et. al attributed the property in (0c) (repeated below) to their observation that it is difficult to nominalize the first complement of yori in the case of subcomparatives.

(0) c. There are no subcomparatives in Japanese (see (0)).

(0) a. The shelf is taller than the door is wide. b. *Kono tana-wa [ano doa-ga hiroi (no) yori] takai. (Beck: (5a)/(74a)) This shelf-TOP that door-NOM wide one YORI tall *the one that the door is wide

7 Once we solve the problem of how individuals are converted to degrees (see 4.3), then the first conjunct, Bill is 6 feet, will not be problematic, either.

18/21 However, the compleiment of yori with no in (0b) itself is not bad acceptable to me. MoreoverYet, (0) is still unacceptable to me.

(0) *Kono tana-wa [ano doa-no hirosa yori] takai This shelf-TOP that door-GEN width YORI tall 'This shelf is taller than the width of that shelf.'

Under the current analysis, the semantic composition is done as in (0).

(0) a. [[AP]] = [[ano doa-no hirosa yori]](x) = [[takai]](x) = 1 (by PM) = x. x exceeds the width of that shelf & x is tall b. [[IP]] = x. x exceeds the width of that shelf & x is tall ([[kono tana]]) <=A = this shelf exceeds the width of that shelf & x is tall. (Intended meaning): The height of this shelf exceeds the width of that shelf & x is tall.

I am still thinking of the solution for this issue.

5. Some issues to be solved 5.1. Compared to

(0) a. Compared to John, Bill is tall. b. Compared to John, Bill is taller.

---If we assume that the Compared to phrase is an adjunct (cf. Beck et. al (2004)), then it seems that (0) is the only possible structure for (0b). What is the semantics like? <=no specific answer yet.

(0) 3 e i t 3 3 Compared to John Bill e 3 is #P

The sentence in (0a), on the other hand, can be ambiguous under the analysis, on the surface; it may be either (0) or (0).

19/21 (0) a. IP t 3 Bill e 3 is AP

b. [[AP]] = [[tall]](x) = [[compared to John]](x) = 1 (by PM) = x is tall & x is compared to John. c. [[IP]] = Bill is tall & Bill is compared to John <= I should ask native speakers if this is compatible with their intuition.

5.2. Another possible structure for yori constructions?

(0) IP 3 r u 3 IP LGB yori 3 NP e I' 3 AP

6. Nakanishi's analysis for sugiru 'to exceed' ---Nakanishi (2004: chap. 4 & to appear) proposes that "[[sugiru]] is the same as [[too]]" (to appear: p. 6) as shown in (0) based on the parallelism in (0).

(0) a. [[too]] = D

(0) a. kono sukaato-wa naga-sugi-ru (=Nakanishi to appear: (1b)) This skirt-TOP long-exceed-PRES b. This skirt is too long.

---Furthermore, she mentions (2004: p. 223, f.n. 9) that "[she] follow[s] the traditional analysis of treating yori as than." The negative prediction is that sugiru and the yori constituent cannot co-occur. But it is not the case.

(0) a. kono sukaato-wa ano sukaato-yori naga-sugi-ru this skirt-TOP that skirt-YORI long-exceed-PRES (Lit.) 'This skirt is too longer than that skirt.' b. kono sukaato-wa ano sukaato-ga naga-sugi-ru-yori naga-sugi-ru this skirt-TOP that skirt-NOM long-exceed-PRES-YORI long-exceed-PRES

20/21 (Lit.) 'This skirt is too longer than that skirt is too long.' c. kono sukaato-wa ano sukaato-ga naga-sugi-ru yori naga-i. this skirt-TOP that skirt-NOM long-exceed-PRES-YORI long-PRES (Lit.) 'This skirt is longer than that skirt is too long.'

---On the other hand, those cast no problem on my analysis.

(0) IP t 3 this skirt-TOP e 3 VP

7. References Beck, Sigrid, Toshiko Oda and Koji Sugisaki (2004) "Variation in the Semantics of Comparison: Japanese vs. English," in Journal of East Asian Linguistics 13-4, pp. 289-344. Bresnan, Joan (1973) "Syntax of the comparative clause construction in English," in Linguistic Inquiry, 4- 3, pp.275-343. Hackl, Martin (2000) Comparative Quantifiers, Doctoral Dissertation, MIT. Heim, Irene (2000) "Degree Operators and Scope," in Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistics Theory (SALT) X, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, pp. 40-64. Ishii, Yasuo (1991) Operators and Empty Categories in Japanese, Ph.D dissertation, The University of Connecticut. Ishii, Yasuo (1999) "Decomposing Japanese Comparatives," in Proceedings of the Nanzan GLOW: The Second GLOW Meeting in Asia, pp. 159-176. Kennedy, Christopher (1997) Projecting the Adjective: The Syntax and Semantics of Gradability and Comparison, Doctoral Dissertation, University of California, Santa Cruz. Kikuchi, Akira (1987) "Comparative Deletion in Japanese," ms., Yamagata University. Kikuchi, Akira (2002) "On the Interpretation of Measure Phrases in English and Japanese," ms., Tohoku University. Lechner, Winfried (2001) "Reduced and Phrasal Comparatives," in NLLT 19-4, pp. 683-735. Nakanishi, Kimiko (2004) Domains of Measurement: Formal Properties of Non-Split/Split Quantifier Constructions, Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania. Nakanishi, Kimiko (To appear) "On Comparative Quantification in the Verbal Domain," in The Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistics Theory (SALT) XIV. Schwarzschild, Roger (2002) "The grammar of measurement," in The Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistics Theory (SALT) XII, pp. 225-245. Schwarzschild, Roger (to appear) " Measure Phrases as Modifiers of Adjective," in Recherches Linguistiques de Vincennes, 35, L'adjectif Schwarzschild, Roger & Karina Wilkinson (2002) "Quantifiers in Comparatives: A Semantics of Degree based on Intervals," in Natural Language Semantics 10, pp. 1-41. von Stechow, Arnim (1984) "Comparing Theories of Comparsion," in Journal of Semantics 3, 1-77.

21/21