Functional Characterizations of Venom Phenotypes in the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus Adamanteus) and Evidence for E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Venomous Snakes of Trinidad & Tobago

Venomous Snakes of Trinidad & Tobago THERE ARE FOUR SPECIES OF DANGEROUSLY VENOMOUS SNAKES NATIVE TO TRINIDAD, AND NONE OCCUR IN TOBAGO VENOMOUS SNAKE IDENTIFICATION As a resident of Trinidad & Tobago, you should learn to identify those regional species that may pose a threat to humans. Then, by process of elimination, all others can be recognized as non-life threatening (non- venomous). Knowing the following characteristics is helpful. CORALSNAKE - Red, black, and pale, whitish rings encircle the body. The black rings are either single (bor- dered by pale, whitish rings) or in triads. Similar non-venomous species (false corals) have black rings in pairs. IF YOU ENCOUNTER A SNAKE WITH RED, BLACK, AND PALE, WHITISH RINGS, ASSUME IT IS VENOMOUS. MAPEPIRE (PIT VIPER) SPECIES - Pupils elliptical and sensory pit present between nostril and eye. HEAD NOR- MALLY TRIANGULAR, BUT BEST NOT TO RELY SOLELY ON THAT CHARACTERISTIC. MILDLY VENOMOUS SPECIES – There are a few species of snakes in Trinidad & Tobago that are not consid- ered potentially deadly, but are capable of injecting mild venom. Different people have differing reactions, so it is advisable to seek medical advice for any snakebite. Even in the absence of venom, snakebites result in puncture wounds that may become infected and need medical attention. The easiest way to recognize the four venomous species is to learn their patterns and coloration, much as you do common birds. Author: Robert A. Thomas, Ph.D. Asa Wright Nature Centre Board Member Center for Environmental Communication Loyola University New Orleans [email protected] Published by Asa Wright Nature Centre, Arima Valley, Trinidad & Tobago, West Indies Special thanks to David L. -

Distribution and Natural History of the Ecuadorian Toad-Headed Pitvipers of the Genus Bothrocophias (Squamata: Serpentes: Viperidae: Crotalinae)

©Österreichische Gesellschaft für Herpetologie e.V., Wien, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at HERPETOZOA 19 (1/2): 17-26 17 Wien, 30. Juli 2006 Distribution and natural history of the Ecuadorian Toad-headed Pitvipers of the genus Bothrocophias (Squamata: Serpentes: Viperidae: Crotalinae) Verbreitung und Naturgeschichte der ecuadorianischen Krötenkopf-Grubenottern der Gattung Bothrocophias (Squamata: Serpentes: Viperidae: Crotalinae) DIEGO F. CISNEROS-HEREDIA & MARIA OLGA BORJA & DANIEL PROANO & JEAN-MARC TOUZET KURZFASSUNG Spärlich sind die Kenntnisse über Grubenottern der Gattung Bothrocophias. Die vorliegende Arbeit enthält Informationen zu drei Bothrocophias Arten aus Ecuador: Bothrocophias campbelli (FREIRE LASCANO, 1991), B. hyoprora (AMARAL, 1935) und B. microphthalmus (COPE, 1875), einschließlich Angaben zur geographischen und vertikalen Verbreitung, zu Nachweisen in den Provinzen, sympatrischen Grubenotternarten, Aktivitätsmustern, Verhalten, Körpergröße, Fortpflanzungsbiologie, Nahrung und Lebensalter. Bothrocophias campbelli bewohnt die nördlichen, zentralen und südlichen Gebiete der pazifischen Andenabhänge Ecuadors zwischen 800 und 2000 m; Bothrocophias hyoprora kommt im nördlichen und südlichen Amazonastiefland und an den unteren östlichen Hän- gen der Anden Ecuadors zwischen 210 und 1500 m vor, Bothrocophias microphthalmus an deren Südosthängen zwischen 600 und 2350 m. Die Arbeit berichtet über den zweiten Fundortnachweis von B. campbelli in der Provinz Imbabura und den westlichsten Fundort von B. hyoprora im Tal des Nangaritza Flusses. Das ympatrische Vorkom- men von B. hyoprora und B. microphthalmus im Makuma-Gebiet, Provinz Morona-Santiago, wird bestätigt, was die bisher bekannte obere Verbreitungsgrenze von B. microphthalmus auf zumindest 600 m anhebt. Das Weiß- bauch-Mausopossum Marmosops noctivagus wird erstmals als Beutetier von B. microphthalmus beschrieben. Die neuen Daten über die Fortpflanzungsbiologie von Grubenottern der Gattung Bothrocophias umfassen Wurfgröße und Körperlänge Neugeborener bei B. -

From Four Sites in Southern Amazonia, with A

Bol. Mus. Para. Emílio Goeldi. Cienc. Nat., Belém, v. 4, n. 2, p. 99-118, maio-ago. 2009 Squamata (Reptilia) from four sites in southern Amazonia, with a biogeographic analysis of Amazonian lizards Squamata (Reptilia) de quatro localidades da Amazônia meridional, com uma análise biogeográfica dos lagartos amazônicos Teresa Cristina Sauer Avila-PiresI Laurie Joseph VittII Shawn Scott SartoriusIII Peter Andrew ZaniIV Abstract: We studied the squamate fauna from four sites in southern Amazonia of Brazil. We also summarized data on lizard faunas for nine other well-studied areas in Amazonia to make pairwise comparisons among sites. The Biogeographic Similarity Coefficient for each pair of sites was calculated and plotted against the geographic distance between the sites. A Parsimony Analysis of Endemicity was performed comparing all sites. A total of 114 species has been recorded in the four studied sites, of which 45 are lizards, three amphisbaenians, and 66 snakes. The two sites between the Xingu and Madeira rivers were the poorest in number of species, those in western Amazonia, between the Madeira and Juruá Rivers, were the richest. Biogeographic analyses corroborated the existence of a well-defined separation between a western and an eastern lizard fauna. The western fauna contains two groups, which occupy respectively the areas of endemism known as Napo (west) and Inambari (southwest). Relationships among these western localities varied, except between the two northernmost localities, Iquitos and Santa Cecilia, which grouped together in all five area cladograms obtained. No variation existed in the area cladogram between eastern Amazonia sites. The easternmost localities grouped with Guianan localities, and they all grouped with localities more to the west, south of the Amazon River. -

Phylogenetic Relationships Within Bothrops Neuwiedi Group

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 71 (2014) 1–14 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Phylogenetic relationships within Bothrops neuwiedi group (Serpentes, Squamata): Geographically highly-structured lineages, evidence of introgressive hybridization and Neogene/Quaternary diversification ⇑ Taís Machado a, , Vinícius X. Silva b, Maria José de J. Silva a a Laboratório de Ecologia e Evolução, Instituto Butantan, Av. Dr. Vital Brazil, 1500, São Paulo, SP 05503-000, Brazil b Coleção Herpetológica Alfred Russel Wallace, Instituto de Ciências da Natureza, Universidade Federal de Alfenas, Rua Gabriel Monteiro da Silva, 700, Alfenas, MG 37130-000, Brazil article info abstract Article history: Eight current species of snakes of the Bothrops neuwiedi group are widespread in South American open Received 8 November 2012 biomes from northeastern Brazil to southeastern Argentina. In this paper, 140 samples from 93 different Revised 3 October 2013 localities were used to investigate species boundaries and to provide a hypothesis of phylogenetic rela- Accepted 5 October 2013 tionships among the members of this group based on 1122 bp of cyt b and ND4 from mitochondrial DNA Available online 17 October 2013 and also investigate the patterns and processes occurring in the evolutionary history of the group. Com- bined data recovered the B. neuwiedi group as a highly supported monophyletic group in maximum par- Keywords: simony, maximum likelihood and Bayesian analyses, as well as four major clades (Northeast I, Northeast Mitochondrial DNA II, East–West, West-South) highly-structured geographically. Monophyly was recovered only for B. pubes- Incomplete lineage sorting Hybrid zone cens. -

Bothrocophias Hyoprora

ISSN 1809-127X (online edition) © 2011 Check List and Authors Chec List Open Access | Freely available at www.checklist.org.br Journal of species lists and distribution N Bothrocophias hyoprora ISTRIBUTIO Squamata, Serpentes, Viperidae, D (Amaral, 1935): Distribution extension in the state of * RAPHIC G Acre, northern Brazil EO G Paulo Sérgio Bernarde , Everton de Souza do Amaral and Marcus Augusto Damasceno do Vale N O [email protected] Universidade Federal do Acre, Campus Floresta, Centro Multidisciplinar, Laboratório de Herpetologia. CEP 69980-000. Cruzeiro do Sul, AC, Brazil. * Corresponding author. E-mail: OTES N Abstract: The Amazonian toadheaded pitviper Bothrocophias hyoprora (Amaral, 1935) is known from Brazil (states of Amazonas and Rondônia), Colombia, eastern Equador, Peru, and Bolivia. We report the first record of this species from the state of Acre (Brazil) in the Serra do Divisor National Park. This record extends the species distribution in 540 km to the southwest of Tabatinga, state of Amazonas, which was the nearest record of this species in Brazilian Amazon. The genus Bothrocophias (Gutberlet and Campbell 2001) comprises five species occurring in northwestern South America in mesic forests such as lowland rainforest and wet montaneB. hyoprora forests, includingand B. microphthalmus cloud forest (Campbell (Cope, and Lamar 2004). Two species of this genusBothrocophias are recorded fromhyoprora Brazil: B. microphthalmus by 1876) (Campbell and Lamar 2004). can be distinguished from the presence of a more upturned snout (vs. less upturned), having most of the subcaudals undivided (vs. most divided), and having a tendencyBothrocophias towards fewer hyoprora ventrals (118–143 lowvs. 137–168) elevation (Campbellequatorial forestsand Lamar of the 2004). -

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: VIPERIDAE Bothro S

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: VIPERIDAE Catalogue of American Amphbians and Reptiles. Powell, R, and R.D. Wittenberg. 1998. Bothrops caribbaeus. Bothro s caribbaeus (Garman) gint Lucia Laneeherd Bothrops subscutatus Gray 1842:47. Type locality, "Demerara." Holotype not designated, but is (G. Underwood, in litt., 8.V111.92, to J.D. Lazell, Jr.: P.J. Stafford, in litt., 26.V11.98), British Museum (Natural History) (BMNH) 1946.1.19.59, an adult female, collected by E. Sabine, date of collection un- known, but likely early 1930s (not examined by authors). Itlcertae sedis (see Nomenclatural History). Bothrops Sabinii Gray 1842:47. Type locality, "Demerara." . - . Syntypes not designated, but are (G. Underwood, in litt., 25 krn 8.VIII.92, to J.D. Lazell, Jr.; P.J. Stafford, in litt.. 26.VII.98). BMNH 1946.1.18.65, a subadult female, 1946.1.19.65. an adult female, 1946.1.19.66, a subadult male, all collected by E. Sabine, dates of collection utiknown (not examined by au- Map. Range of Borhrops caribbaeus (modified from Lazell 1964 and thors). Incertae sedis (see Nomenclatural History). Schwm. and Henderson 1991): the restricted type locality is niarked Bothrops cinereus Gray 1842:47. Type locality, "America," al- with a circle. dots indicate s. though Gray ( 1849) indicated "South America." Holotype not designated, but is (P.J. Stafford, in litt., 26.V11.98), BMNH 1946.1.18.77, a subadult female, collected by E. MacLeay, date of collection unknown, but likely before 1937; the origi- nal label is missing from this bottle (not examined by au- thors). Incertae seclis (see Nomenclatural History). -

Lachesis Stenophrys) in a European Zoo

The Herpetological Bulletin 151, 2020: 24-27 SHORT NOTE https://doi.org/10.33256/hb151.2427 First report of reproduction in captivity of the Central American bushmaster (Lachesis stenophrys) in a European zoo ÁLVARO CAMINA1*, NICOLÁS SALINAS, IGNACIO GARCIA-DELGADO1, BORJA BAUTISTA1,2, GUILLERMO RODRIGUEZ1, RUBÉN ARMENDARIZ1, LORENZO DI IENNO2, ALICIA ANGOSTO3, RUBÉN HERRANZ4 & GREIVIN CORRALES5 1Grupo Atrox, Parque Temático de la Naturaleza Faunia Avenida de las Comunidades, 28 28032 Madrid, Spain 2Mastervet Mirasierra, Calle de Nuria, 57, 28034 Madrid, Spain 3Alicia Angosto Ecografía Veterinaria, Mallorca, Spain 4Zoopinto, Camino de San Antón, 6, 28320 Pinto, Madrid, Spain 5Instituto Clodomiro Picado, Sección Serpentario, Facultad de Microbiología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] he Central American bushmaster (Lachesis stenophrys) T(Fig.1) is a large species of pit viper. The males are a little longer than the females, averaging of 2-2.10 m and 1.9-2.05 m respectively (Solórzano, 2004). The species lives along the Caribbean versant of Nicaragua to western and central Panama (Campbell & Lamar, 2004), and in Costa Rica is found in tropical wet and subtropical rainforest on the Caribbean versant (Corrales et al., 2014) where the rainfall is very high (3500-6000 mm annual range). Although it can be found at altitudes of 100-700 m its preferences are thought to be 200- 400 m (Ripa, 2002). Lachesis spp. are the only pit vipers on the American continent that lay eggs instead of giving birth to live young (Campbell & Lamar, 2004; Solórzano, 2004). The eggs are deposited in subterranean cavities and the shelters of Figure 1. -

Popular Names for Bushmaster (Lachesis Muta) and Lancehead

Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical Journal of the Brazilian Society of Tropical Medicine Vol.:52:e-20180140, 2019 doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0140-2018 Short Communication Popular names for bushmaster (Lachesis muta) and lancehead (Bothrops atrox) snakes in the Alto Juruá region: repercussions for clinical-epidemiological diagnosis and surveillance Ageane Mota da Siva[1, 2], Wuelton Marcelo Monteiro[3, 4] and Paulo Sérgio Bernarde[2,5] [1]. Instituto Federal do Acre, Campus de Cruzeiro do Sul, Cruzeiro do Sul, AC, Brasil. [2]. Programa de Pós-Graduação Bionorte – Universidade Federal do Acre – UFAC, Rio Branco, Acre, Brasil. [3]. Fundação de Medicina Tropical Dr. Heitor Vieira Dourado, Manaus, AM, Brasil. [4]. Universidade do Estado do Amazonas, Manaus, AM, Brasil. [5]. Laboratório de Herpetologia, Centro Multidisciplinar, Campus Floresta, Universidade Federal do Acre, Cruzeiro do Sul, AC, Brasil. Abstract Introduction: The popular names “surucucu” and “jararaca” have been used in literature for Lachesis muta and Bothrops atrox snakes, respectively. We present the popular names reported by patients who suffered snakebites in the Alto Juruá region. Methods: Fifty-seven (76%) patients saw the snakes that caused the envenomations and were asked about their popular names and sizes. Results: The snakes Bothrops atrox, referred to as “jararaca,” were recognized as being mainly juveniles (80.7%) and “surucucu” as mainly adults (81.8%). Conclusions: The name “surucucu” is used in the Alto Juruá region for the snake B. atrox, mainly for adult specimens. Keywords: Snakebites. Ophidism. Venomous snakes. Amazonia. State of Acre. The bushmaster (Lachesis muta) is the largest venomous The rarity of this species is also reflected in the few existing snake in South America, at over three meters in length. -

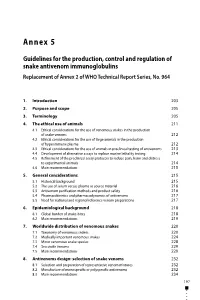

Guidelines for the Production, Control and Regulation of Snake Antivenom Immunoglobulins Replacement of Annex 2 of WHO Technical Report Series, No

Annex 5 Guidelines for the production, control and regulation of snake antivenom immunoglobulins Replacement of Annex 2 of WHO Technical Report Series, No. 964 1. Introduction 203 2. Purpose and scope 205 3. Terminology 205 4. The ethical use of animals 211 4.1 Ethical considerations for the use of venomous snakes in the production of snake venoms 212 4.2 Ethical considerations for the use of large animals in the production of hyperimmune plasma 212 4.3 Ethical considerations for the use of animals in preclinical testing of antivenoms 213 4.4 Development of alternative assays to replace murine lethality testing 214 4.5 Refinement of the preclinical assay protocols to reduce pain, harm and distress to experimental animals 214 4.6 Main recommendations 215 5. General considerations 215 5.1 Historical background 215 5.2 The use of serum versus plasma as source material 216 5.3 Antivenom purification methods and product safety 216 5.4 Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antivenoms 217 5.5 Need for national and regional reference venom preparations 217 6. Epidemiological background 218 6.1 Global burden of snake-bites 218 6.2 Main recommendations 219 7. Worldwide distribution of venomous snakes 220 7.1 Taxonomy of venomous snakes 220 7.2 Medically important venomous snakes 224 7.3 Minor venomous snake species 228 7.4 Sea snake venoms 229 7.5 Main recommendations 229 8. Antivenoms design: selection of snake venoms 232 8.1 Selection and preparation of representative venom mixtures 232 8.2 Manufacture of monospecific or polyspecific antivenoms 232 8.3 Main recommendations 234 197 WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization Sixty-seventh report 9. -

Timber Rattlesnakes Are More Likely to Select Sites That Are Located Near Areas in Which They Have Had Previous Feeding Experiences

Rattlesnake Viperidae Family Crotalus and Sistrulus Maureen De Leon Herpetology November 29, 2007 Dr. Jennifer Dever Introduction When most humans hear any rattling sound in nature, one thing comes to mind: there is a rattlesnake nearby. Flee for safety! Rattlesnakes, Crotalus and Sistrulus, are infamously perceived as evil predators that crave a bite of human flesh. Interestingly enough, human nature and societal influence have given all snakes the reputation of being dangerous, harmful, and poisonous predators. In 1998, Rubio brings about evidence of human fear and common misperceptions resulting in the persecution and even death of more snakes than any other living creature. While some religious cultures regard some members of Serpentes as figures of worship, most cultures treat them as enemies or weapons. For instance, during the late 1980’s crack cocaine epidemic, a suspected house in Colorado was raided. As a result, a stash was discovered being guarded vigilantly by nothing other than the large Western Diamondback Rattlesnake. Congruent with the belief that rattlesnakes are harmful predators, Crotalus and Sistrulus have developed specific adaptations contributing to their overall success of prey capturing and survival. Nevertheless, some prey counteract with defense mechanisms, which then cause rattlesnakes to retreat. Their unique characteristics, sensory adaptations and abilities to tackle environmental pressures have made rattlesnakes interesting creatures for herpetologists to study. History Rattlesnakes are known as members of the Viperidae family and Crotalinae subfamily, also commonly known as pit-vipers. The Crotalinae subfamily accounts for the rattlesnake and approximately fifteen other genra distributed widely in America and southern Asia (Stafford, 2000). In fact, herpetologists hypothesized Viperidae snakes to have originated in Africa and later migrating to Asia, specifically parts of India (Douglas et.al, 2006). -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Revista de Biología Tropical ISSN: 0034-7744 ISSN: 2215-2075 Universidad de Costa Rica Solórzano, Alejandro; Sasa, Mahmood Redescription of the snake Lachesis melanocephala (Squamata: Viperidae): Designation of a neotype, natural history, and conservation status Revista de Biología Tropical, vol. 68, no. 4, 2020, October-, pp. 1387-1400 Universidad de Costa Rica DOI: https://doi.org/10.15517/RBT.V68I4.42359 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44966323031 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative ISSN Printed: 0034-7744 ISSN digital: 2215-2075 Redescription of the snake Lachesis melanocephala (Squamata: Viperidae): Designation of a neotype, natural history, and conservation status Alejandro Solórzano1* & Mahmood Sasa2 1. Museo de Zoología, Universidad de Costa Rica, Ciudad Universitaria Rodrigo Facio, San Pedro de Montes de Oca, San José, Costa Rica; [email protected] 2. Instituto Clodomiro Picado y Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, Ciudad Universitaria Rodrigo Facio, San Pedro de Montes de Oca, San José, Costa Rica; [email protected] * Correspondance Received 18-VI-2020. Corrected 18-VIII-2020. Accepted 11-IX-2020. ABSTRACT. Introduction: The Black-headed Bushmaster (Lachesis melanocephala) is a large venomous snake that inhabits tropical moist forest, wet forest, montane and premontane wet forest in Southwestern Costa Rica and extreme Western Panama. Objective: We assign a neotype for the species due to the loss of the original holotype and update the information on its geographical distribution, natural history, and conservation status. -

Species Description Taxonomy Distribution

Bushmaster Species Description Bushmasters are one of the largest vipers in the world. They are the longest vipers; while Gabon Vipers and Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnakes are the heaviest vipers in the world. There have been reports of bushmasters measuring up to 14 feet but it is more likely that 12 feet is the maximum length. Bushmasters are sexually dimorphic in size with males reaching larger sizes. Photo: Brian Eisele Bushmasters are incredibly beautiful snakes with a pinkish tan, orangish tan, reddish brown or yellowish color with a series of dark markings down the back. Younger snakes usually have a darker ground color and lighter marking on their back relative to adult animals. Overall, there is a great deal of variation in color within and among bushmaster species. However, there are some color differences such as melanocephal; having a very dark head. In addition, bushmasters found in Central America often have wider heads with blunter snouts while bushmasters in the Amazon, especially those in the Guiana Shield have a narrower lancehead shape to the head. The middorsal scales or scales that run down the middle of the back have raised knoblike keels. The keels get smaller as you go towards the tail. Bushmaster’s fangs can be over two inches long and rival the Gabon Viper for longest fang length in snakes. Taxonomy The bushmaster was first described by F. M. Daudin in 1803 and the genus name came from one of the Three Fates in Greek Mythology. Lachesis is a goddess that measures the thread of life or how long each person will live.