North Augusta Middle Lesson Plan LITERACY

Teacher: _MODE______

Grade/ Subject: ___Art 6-8______

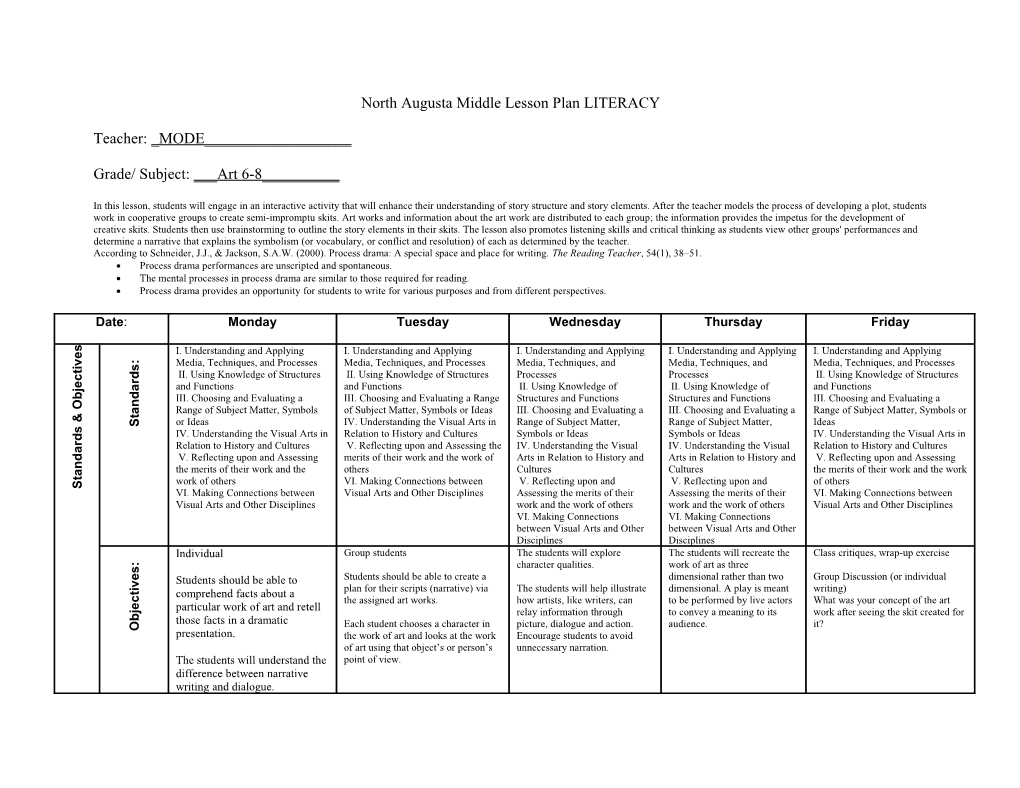

In this lesson, students will engage in an interactive activity that will enhance their understanding of story structure and story elements. After the teacher models the process of developing a plot, students work in cooperative groups to create semi-impromptu skits. Art works and information about the art work are distributed to each group; the information provides the impetus for the development of creative skits. Students then use brainstorming to outline the story elements in their skits. The lesson also promotes listening skills and critical thinking as students view other groups' performances and determine a narrative that explains the symbolism (or vocabulary, or conflict and resolution) of each as determined by the teacher. According to Schneider, J.J., & Jackson, S.A.W. (2000). Process drama: A special space and place for writing. The Reading Teacher, 54(1), 38–51. Process drama performances are unscripted and spontaneous. The mental processes in process drama are similar to those required for reading. Process drama provides an opportunity for students to write for various purposes and from different perspectives.

Date: Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday

s I. Understanding and Applying I. Understanding and Applying I. Understanding and Applying I. Understanding and Applying I. Understanding and Applying e : v Media, Techniques, and Processes Media, Techniques, and Processes Media, Techniques, and Media, Techniques, and Media, Techniques, and Processes i s t

d II. Using Knowledge of Structures II. Using Knowledge of Structures Processes Processes II. Using Knowledge of Structures c r e a j and Functions and Functions II. Using Knowledge of II. Using Knowledge of and Functions d b III. Choosing and Evaluating a III. Choosing and Evaluating a Range Structures and Functions Structures and Functions III. Choosing and Evaluating a n O

a Range of Subject Matter, Symbols of Subject Matter, Symbols or Ideas III. Choosing and Evaluating a III. Choosing and Evaluating a Range of Subject Matter, Symbols or t &

S or Ideas IV. Understanding the Visual Arts in Range of Subject Matter, Range of Subject Matter, Ideas s IV. Understanding the Visual Arts in Relation to History and Cultures Symbols or Ideas Symbols or Ideas IV. Understanding the Visual Arts in d r Relation to History and Cultures V. Reflecting upon and Assessing the IV. Understanding the Visual IV. Understanding the Visual Relation to History and Cultures a

d V. Reflecting upon and Assessing merits of their work and the work of Arts in Relation to History and Arts in Relation to History and V. Reflecting upon and Assessing n the merits of their work and the others Cultures Cultures the merits of their work and the work a t work of others VI. Making Connections between V. Reflecting upon and V. Reflecting upon and of others S VI. Making Connections between Visual Arts and Other Disciplines Assessing the merits of their Assessing the merits of their VI. Making Connections between Visual Arts and Other Disciplines work and the work of others work and the work of others Visual Arts and Other Disciplines VI. Making Connections VI. Making Connections between Visual Arts and Other between Visual Arts and Other Disciplines Disciplines Individual Group students The students will explore The students will recreate the Class critiques, wrap-up exercise

: character qualities. work of art as three s

e Students should be able to Students should be able to create a dimensional rather than two Group Discussion (or individual v

i plan for their scripts (narrative) via The students will help illustrate dimensional. A play is meant writing) t comprehend facts about a c the assigned art works. how artists, like writers, can to be performed by live actors What was your concept of the art

e particular work of art and retell j relay information through to convey a meaning to its work after seeing the skit created for b those facts in a dramatic Each student chooses a character in picture, dialogue and action. audience. it? O presentation. the work of art and looks at the work Encourage students to avoid of art using that object’s or person’s unnecessary narration. The students will understand the point of view. difference between narrative writing and dialogue. Essential Question(s) Essential Question:ALL WHATDIDEssential IT MEAN?? of concepts How the VI. utilize STEAM? did I change art could same differentwork? I this dothe or Whatif V. would I figures. /or events to current yourhistorical and or and AsIevents arts,compare civilizations, situation IV. throughthe learn people processesideas. to support useyour thinking constructive your and examples III. Explain art in How the room? functionII. doI effectively vocabulary. principlesUse Ielements art? How of the and appropriate I. use did EQ: Closure, Lesson SummaryBell Ringer, Guided Practice, Independent Practice, Lesson Activities for DO-NOW timefor checklist start of a prompts Create Clean-up STANDARD: VA1 Closure/Reflection: (See Learningobjective Objective) and lesson the Discuss storytelling, etc.) symbolism, pattern, lesson. (Shape, of focus the Discuss the element Practice: Independent project assessmentthe and for activities, objectives, define Instructor will VA5 STANDARD: Guided Instruction: Friday. and on Monday due assigned All sketches are instructor. by the determined sketches as individual work on studentwill Each manner. orderly in willan arrive Students STANDARD: VA1 Do Now:

VA2, VA4, VA3, Friday and on Monday due assigned All sketches are instructor. by the determined sketches as individual work on studentwill Each manner. orderly in willan arrive Students STANDARD: VA1 Do Now: solution? Does anyonehave achallenging. Share something wasGROUP: that Clean-up STANDARD: VA1 Closure/Reflection: view. of person’s point or of using object’s work that art and work looks the the art of at a character studentchooses inEach art works. assigned the via (narrative) scripts for plan their able should to a create be Students Practice: Independent project assessmentthe and for activities, objectives, define Instructor will VA5 STANDARD: Guided Instruction: .

VA2, VA4, VA3, Monday andFriday.Monday due sketches are on All assigned instructor. bythe determined as sketches work onwill individual student orderly Each manner. in willan arrive Students STANDARD: VA1 Do Now: addressed beforeaddressed performance. items needto that be minutes checklist last of a Create Clean-up STANDARD: VA1 Closure/Reflection met. are criteria all skit, that the ensuring Practice dialog. a create skills, Using storytelling skit. toin cover the points outlineof an major Create worksheets. the provided information in the skit utilizing semi-impromptu groups,students a create In Practice: Independent project assessmentthe and for activities, objectives, define Instructor will VA5 STANDARD: Guided Instruction:

VA2, VA4, VA3, : assigned on Monday andFriday. on Monday due assigned All sketches are instructor. the determined sketches as by individual work on studentwill Each manner. orderly in willan arrive Students STANDARD: VA1 Do Now: COMMENT for one of the of COMMENT for one groups. Leave a Lot: Parking KIND Clean-up STANDARD: VA1 Closure/Reflection: closerart look at Begin a expectations Review audience etiquette. Review Practice: Independent project assessmentthe and for activities, objectives, define Instructor will STANDARD: Guided Instruction:

VA2, VA4, VA3, VA5 you previously. didn’tknow of art one that about the works you learned that Share something OUT THETICKET DOOR: Clean-up STANDARD: VA1 Closure/Reflection: gains for personal critique Formative Practice: Independent project assessmentthe and for activities, objectives, define Instructor will VA5 STANDARD: Guided Instruction: dueand Friday. on Monday assigned sketches are All instructor. by the determined sketches as on individual work studentwill Each manner. orderly in willan arrive Students STANDARD: VA1 Do Now:

VA2, VA4, VA3,

Homework/ Assessment STEAM CoDnifnfercetniotniastion Strategy(s)Small Group Task Extension self-assessment, self-assessment, Student Summative: thinking deeper evoke to of line questioning initiating student, with Discussion Formative: Assessment: Mathematics Art + Engineering Art + Technology Art + Science Art + Connection: STEAM environment. 4) Learning and 3) Product, 2) Process, 1) Content, Differentiation: Groups Cooperative Small GroupTask: of project (Rubric)of Diagnostic: assessment Teacher Making newcolors Making color Creating Proportional colormixes Digital recordingoflesson

Completion 2) Process, 2) Process, 1) Content, Differentiation: Groups Cooperative Small GroupTask: of project (Rubric)of Diagnostic: assessment Teacher self-assessment, Student Summative: thinking deeper evoke to of line questioning initiating student, with Discussion Formative: Assessment: Mathematics Art + Engineering Art + Technology Art + Science Art + Connection: STEAM environment. 4) Learning and 3) Product, Making newcolors Making color Creating Proportional colormixes Digital recordingoflesson

Completion 2) Process, 2) Process, 1) Content, Differentiation: Peer Pairing Small GroupTask: n of (Rubric)of project n Diagnostic: assessment Teacher self-assessment, Student Summative: thinking deeper evoke to of line questioning initiating student, with Discussion Formative: Assessment: Symmetry Mathematics Art + Engineering Art + waysinnovative Technology Art + Science Art + Connection: STEAM environment. 4) Learning and 3) Product, Making newcolors Making PrismIsaac Newton, Measurement, Using oldtoolsin

Completio 2) Process, 2) Process, 1) Content, Differentiation: Groups Cooperative Small GroupTask: project (Rubric) project Diagnostic: assessment Teacher assessment, Student self- Summative: thinking deeper evoke to questioning ofline initiating student, withDiscussion Formative: Assessment: symmetry Mathematics Art + ways Engineering Art + Technology Art + Science Art + Connection: STEAM environment. 4) Learning and 3) Product, Using old toolsininnovative Using old Floral anatomy Proportions, measurements, Proportions, measurements, SmartBoard usage

Completion ofCompletion of project (Rubric)of Diagnostic: assessment Teacher self-assessment, Student Summative: thinking deeper evoke to of line questioning initiating student, with Discussion Formative: Assessment: symmetry measurements, Mathematics Art + waysinnovative Engineering Art + Technology Art + Science Art + Connection: STEAM environment. 4) Learning and 3) Product, 2) Process, 1) Content, Differentiation: discussion Small group Small GroupTask: Using old toolsin Using old Floral Anatomy Proportions, SmartBoard usage

Completion

Comments: tome. and areconcepts that new tolearnabout more ideas I dowhateverI need to do seeright.if I’m informationcheckand to conclusionsabout makeinferences drawand I usemy own knowledgeto are. informationI’mstudying important parts of the I whatcan thetell most 4 General General CriticalThinkingRubric Vocabulary:Creativity, imagination, symbolism, character profile,

Parent Contacts Parent letters gohome Parent letters me. areconcepts that new to aboutmore ideas and make I aneffort learn to checkto I’m seeif right. information, I and usually inferences about conclusions makeand usewhat II know to draw information. important most about can usually I tell whatis 3 Parent letters gohome Parent letters me. conceptsthat are new to and learnmore about ideas Ifsomeone reminds I me, forthem. reasons I dohave not good information,sometimesbut inferencesabout help, With make I unimportant details. ideasmixed upwith SometimesI importantget 2 opinion. cannot explainI my findbother to more. out andinformation donot alreadywhat I about know am I with usually happy inferences. have I difficultymaking and important whatisn’t. differencebetween what’s usually can’t I tell the 1 Collaboration Rubric

Traits 4 3 2 1 Contribution I contribute I share many ideas and I contribute I choose not to to Group consistently and contribute relevant inconsistently to the participate actively to the group information group I do not complete my discussions I encourage other I complete my assigned assigned tasks I accept and perform members to share their tasks with I get in the way of the all of the tasks ideas encouragement goal setting process I take on I help the I balance my listening I contribute I delay the group from group set goals and speaking sporadically in setting meeting goals I help direct the group I’m concerned about our goals in meeting our goals others’ feelings and I have trouble in ideas meeting goals Cooperation I share many ideas and I share ideas when I share ideas I don’t like to share my with Group contribute relevant encouraged occasionally when ideas information I allow all members to encouraged I do not contribute to I encourage other share I allow sharing by most group discussions members to share their I can listen to others group members I interrupt when others ideas I show sensitivity to I listen to others are sharing I balance my listening other people’s feelings sometimes I do not listen to others and speaking and ideas I consider other I’m not considerate of I’m concerned about people’s feelings and others’ feelings and others’ feelings and ideas sometimes ideas ideas Comments (Teacher)

Comments (Student) Differentiation:

Direct Instruction Structured Overview Explicit Teaching Mastery Lecture Drill and Practice Compare and Contrast Didactic Questions Demonstrations

Indirect Instruction Problem Solving Case Studies Inquiry Reading for Meaning Reflective Discussion Concept Formation

Common Essential Learning Communication Critical and Creative Thinking Independent Learning Technological Literacy Personal and Social Values and skills

Interactive Instruction Role Playing Brainstorming Peer Practice Discussion Cooperative Learning Groups Problem Solving Circle of Knowledge Tutorial Groups Resources Human Manipulatives Print Non-Print ( e.g., software, video) Technology Other Subject Areas

A few years ago, I showed my sixth graders The Gulf Stream by Winslow Homer. It's an epic painting of a young black sailor in a small broken boat, surrounded by flailing sharks, huge swells, and a massive storm in the distance. I asked my students the simple question, "What's happening?" The responses ranged from "He's a slave trying to escape" to "He's a fisherman lost at sea." The common theme with the responses, though, was the tone -- most students were very concerned for his welfare. "That boat looks rickety. I think he’s going to get eaten by the sharks," was a common refrain. Then a very quiet, shy girl raised her hand. "It's OK, he'll be fine," she said. "The ship will save him." The room got quiet as everyone stared intently at the painting. I looked closely at it. "What ship?" I responded. The young girl walked up to the image and pointed to the top left corner. Sure enough, faded in the smoky distance was a ship. This revelation changed the tone and content of the conversation that followed. Some thought it was the ship that would save him. Others thought it was the ship that cast him off to his death. Would the storm, sharks, or ship get him? The best part of this intense debate was hearing the divergent, creative responses. Some students even argued. The written story produced as a result of analyzing this image was powerful. Since this experience, I have developed strategies that harness the power of observation, analysis, and writing through my art lessons. Children naturally connect thoughts, words, and images long before they master the skill of writing. This act of capturing meaning in multiple symbol systems and then vacillating from one medium to another is called transmediation. While using art in the classroom, students transfer this visual content, and then add new ideas and information from their personal experiences to create newly invented narratives. Using this three-step process of observe, interpret, and create helps kids generate ideas, organize thoughts, and communicate effectively. It’s Alive Step 1: Observe Asking students to look carefully and observe the image is fundamental to deep, thoughtful imagination and fact collecting. Keep this in mind when choosing art to use in class. Look for images with: Many details: If it is a simple image, there's not much to analyze. Characters: There should be people or animals in the image to write about. Colors: Find colors that convey a mood. Spatial relationships: How do the background and foreground relate? Lead your students through the image. "I like it" is not the answer we are looking for. Ask questions that guide the conversation. Encourage divergent answers and challenge them. Try these questions: What characters do you see? Do they remind you of anything? What colors do you see? How do those colors make you feel? What images within the artwork do you see? How are they made? Do you see any unusual textures? What do they represent? What is the focal point of the image? How did the artist bring your attention to the focal point? How did the artist create the illusion of space in the image? If you were living in the picture and could look all around you, what would you see? If you were living in the picture, what would you smell? What would you hear? Keep your questions open-ended, and record what students say so that they'll have a reference for later. Identify and challenge assumptions. At this point, we are not looking for inferences or judgments, just observations.

Step 2: Make Inferences by Analyzing Art Once they have discussed what they see, students then answer the question, "What is happening?" They must infer their answers from the image and give specific reasons for their interpretations. For example, while looking at The Gulf Stream, one student said, "The storm already passed and is on its way out. You can tell because the small boat the man is on has been ripped apart and the mast is broken." That is what we are looking for in their answers: rational thoughts based on inferences from data in the picture. No two responses will be exactly the same, but they can all be correct as long as the student can coherently defend his or her answer with details from the image. When children express their opinions based on logic and these details, they are analyzing art and using critical thinking skills. Here are some tips to model a mature conversation about art: Give adequate wait time. We are often so rushed that we don't give children time to think and reflect. Ask students to listen to, think about, and react to the ideas of others. Your questions should be short and to the point. Highlight specific details to look at while analyzing art (characters, facial expressions, objects, time of day, weather, colors, etc.). Explain literal vs. symbolic meaning (a spider's web can be just that, or it can symbolize a trap). Step 3: Create After thoughtful observation and discussion, students are abuzz with ideas. For all of the following writing activities, they must use details from the image to support their ideas. Here are just a few of the many ways we can react to art: For Younger Students: Describe time of day and mood of scene. Describe a character in detail with a character sketch. Characters may be people, animals, or inanimate objects. Write a story based on this image. Give students specific vocabulary that they must incorporate into their story. For Older Students: Write down the possible meaning of the image, trade with a partner, and persuade your partner to believe that your story is the correct one based on details in the image. Identify characters and their motives. Who are they and what do they want? Explain how you know based on details. Pretend that you are in the image, and describe what you see, smell, feel, and hear. Describe the details that are just outside of the image, the ones we can’t see. Introduce dialogue into your story. What are they saying? Sequence the events of the story. What happened five minutes before this scene, what is happening now, and what happens five minutes later? How do you know? Create from the perspective of one of the characters in the image. Explain who is the protagonist and antagonist. What is their conflict?

Thinking and Communicating We don’t know what the future holds for our students, but we do know that they will have to think critically, make connections, and communicate clearly. Art can help students do that. Fareed Zakaria said, "It is the act of writing that forces me to think through them [ideas] and sort them out." Art can be that link to helping students organize their ideas and produce coherent, thoughtful writing. As you consider teaching writing through art, “What if children were introduced to key qualities of good writing in the context of illustrations?”

This question led to the research behind In Pictures and In Words by Kate Wood Ray. Also refer to Beth Olshansky's PictureWriting.org website. Jan Van Eyck's Arnolfini "Wedding" Portrait

"...[M]eaning is neither found nor given, but that it takes shape arbitrarily, and that it is dependent upon associations and circumstances that scholars, artists, and viewers all bring to their engagement with paintings. It is not constructed by any one of them alone, although each of us is responsible for the orchestration of our own responses..." (Linda Seidel, Jan Van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait: Stories of an Icon, Cambridge University Press, 1993, p. 14).

Seidel reminds us in the quotation above that we should not understand our role as a passive one in which we simply reflect the "found" or "given" meaning of a work of art. Instead we need to take an active stance in relationship to the work and make or construct our own understanding of the meaning of a work of art. Seidel describes the role of the art historian as a narrator or story teller. This will be the stance I want us take in considering one of the major examples of Northern Renaissance art, Jan van Eyck's so- called Arnolfini Wedding Portrait.

In preparation for our class discussion, I want you to begin to create your own story about the painting. Consider the following gallery of details and try to explain how they fit into your story.

Ordinance with the Seal of Duke Philip the Good, June 20, 1434. Stadsarchief, Bruges. Politieke Charters, no. 987.

The following excerpt is from Gardner's Art Through the Ages (pp. 576-578). It gives you a standard textbook account of the painting:

The intersection of the secular and religious in Flemish painting also surfaces in Jan van Eyck's double portrait Giovanni Arnolfini and His Bride. Van Eyck depicts the Lucca financier (who had established himself in Bruges as an agent of the Medici family) and his betrothed in a Flemish bedchamber that is simultaneously mundane and charged with the spiritual. As in the Mérode Altarpiece , almost every object portrayed conveys the event's sanctity, specifically, the holiness of matrimony. Arnolfini and his bride, Giovanna Cenami, hand in hand, take the marriage vows. The cast-aside clogs indicate this event is taking place on holy ground. The little dog symbolizes fidelity (the common canine name Fido originated from the Latin fido, "to trust"). Behind the pair, the curtains of the marriage bed have been opened. The bedpost's finial (crowning ornament) is a tiny statue of Saint Margaret, patron saint of childbirth. From the finial hangs a whisk broom, symbolic of domestic care. The oranges on the chest below the window may refer to fertility, and the all-seeing eye of God seems to be referred to twice. It is symbolized once by the single candle burning in the left rear holder of the ornate chandelier and again by the mirror, where viewers see the entire room reflected. The small medallions set into the mirror's frame show tiny scenes from the Passion of Christ and represent God's ever- present promise of salvation for the figures reflected on the mirror's convex surface.

Van Eyck enhanced the documentary nature of this painting by exquisitely painting each object. He carefully distinguished textures and depicted the light from the window on the left reflecting off various surfaces. The artist augmented the scene's credibility by including the convex mirror, because viewers can see not only the principals, Arnolfini and his wife, but also two persons who look into the room through the door. One of these must be the artist himself, as the florid inscription above the mirror, "Johannes de Eyck fuit hic," announces he was present. The picture's purpose, then, seems to have been to record and sanctify this marriage. Although this has been the traditional interpretation of this image, some scholars recently have taken issue with this reading, suggesting that Arnolfini is conferring legal privileges on his wife to conduct business in his absence. Despite the lingering questions about the precise purpose of Giovanni Arnolfini and his Bride, the painting provides viewers today with great insight into both van Eyck's remarkable skill and Flemish life in the fifteenth century. Characters:

An early sixteenth century inventory record apparently referring to the London painting identifies the man in the painting as: "Arnoult-fin." This appears to be a French version of the Italian name Arnolfini. There were several members of this family from Lucca in northern Europe during this period. In cities like Paris and Bruges there were colonies of Italian merchant families during this period. These families were actively engaged in the cloth industry and other luxury materials catering to the needs of the nobility of northern Europe. Many of these families also became involved with banking. Antonius Sanderus in the seventeenth century provides us with a view of the so-called Bourse or financial neighborhood in Bruges. The dominant buildings identified in the illustration are the Domus Florentinorum and the Domus Genuensium, or the Florentine and Genoese houses. The account records of northern European princes have frequent entries recording loans given by these Italian merchants to help support the need for liquid capital to support the princely households. The Arnolfini referred to in the inventory is most likely Giovanni di Arrigo Arnolfini who was born in Lucca about 1400. He appears to have settled in Bruges by 1421. An entry in the Bruges Archives for July 1 of that year records that Giovanni made a large sale of silks and hats. By at least 1423, Giovanni was engaged in transactions with the duke. There was a large payment that year from the duke for a series of six tapestries with scenes of Notre Dame. These were intended as a present to the Pope. There is a record from 1446 listing a loan by Giovanni to Philip the Good. Perhaps in exchange for the loan, Philip gave Giovanni the right to collect tariffs on goods imported from England that entered through Gravelines for a period of six years. This lucrative privilege was renewed for another six years. In 1461, Giovanni became a councillor and chamberlain to the duke, and he was knighted in 1462. Louis XI of France appointed Arnolfini a councillor and Governor of Finance of Normandy. Giovanni died in 1472 and was buried in the chapel of the Lucchese merchants at the Augustinian church in Bruges, where he and his wife had endowed daily and anniversary masses in their name. Giovanni married Giovanna Cenami the daughter of one of the most prominent Lucchese families established in northern Europe. Giovanna's grandmother was the niece of Dino Rapondi who along with his three brothers were close financial advisors and bankers for the Dukes Philip the Bold, John the Fearless, and Philip the Good of Burgundy at the end of the fourteenth century and the beginning of the fifteenth century. In 1432 when the last of the four Rapondi brothers died, Philip the Good had a special mass sung for them. Marriage alliances like that between the Cenami and Rapondi families were not private but public matters with the futures of the families' businesses inextricably linked. For Giovanni Arnolfini marrying into such a prominent family as the Cenamis was undoubtedly a significant boost to his financial fortunes. Unfortunately, we do not know which year they were married. So while not certain, the identification of the couple as Giovanni Arnolfini and Giovanna Cenami seems likely.

We know that the couple died childless. We should be cautious not to assume that they never had any children since they perhaps had children that predeceased them. At the same time there is no evidence that they did have children. We do have records of Giovanni having an extra-marital affair. In 1470, thus late in Giovanni's life, a woman took him to court to have returned to her jewelry he had given her. She also sought a pension and several houses that she had been promised.

An important part of our discussion about the Arnolfini portrait will be the idea of the unseen presence. Here this master of illusionistic representation calls attention to what cannot be shown directly, and that is God. There is probably also another unseen presence, and that is Philip the Good. It is unlikely that Arnolfinis or the Cenamis approached Jan van Eyck directly to paint the double portrait. Since Jan van Eyck was the court painter for Philip the Good, the Arnolfinis or the Cenamis would have at least needed the duke's permission to have van Eyck to do the painting. Jan's signature documents his role as witness to the event, and as a member of the ducal court, van Eyck was likely serving as the duke's representative. Thus his signature carries with it both personal and ducal sanction. Jean Wilson has taken this another step and understood the painting as a gift of Philip the Good to the couple (Painting in Bruges at the Close of the Middle Ages, p. 64). The painting can be seen to attest to the Arnolfini's membership in the household of the duke. A Wedding Portrait?

While most scholars agree that the painting depicts Giovanni Arnolfini and Giovanna Cenami, Erwin Panofsky's assumption that the painting is a wedding portrait has been called into question. Compare the Arnolfini painting to the following works:

Right panel of Rogier van der Weyden's Altarpiece of Master of the Tiburtine Sibyl, Scenes from the Life of the the Seven Sacraments, painted for Jean Chevrot. Virgin. Marriage of the Virgin is in the foreground.

Whether this is a wedding portrait or not it is important to see the painting in the context of the social and institutional attitudes towards marriage. Consult the excerpts from Dale Kent's essay "Women in Renaissance Florence." While not dealing with the Netherlands, the article is still relevant. Remember that the Arnolfinis and Cenamis come from Lucca which is very close to Florence.

Is she or isn't she?

I have never taught the Arnolfini Portrait without a student asking the question whether she is pregnant. Compare the dress worn by Giovanna Cenami to that worn by St. Catherine on the right wing of the Dresden triptych: Harley 4431: Christine de Pizan presenting her collected works to Isabeau de Bavière. Pierre Salmon talking with King Charles VI Dresden Triptych. (see Salmon Frontispieces)

Author Presenting Book to the Duke of Jean Miélot presenting his translation of the Traité sur l'Oraison Burgundy Dominicale to Philip the Good. Histoire de la conquete de la Toison d'Or (see Burgundian Frontispieces) (see Burgundian Frontispieces) Images of Bedrooms: Compare the Arnolfini bedchamber to that belonging to the wife of a merchant described by Christine de Pizan in her Livre de la trois vertus. An Empty Throne?

Dome of the Orthodox Baptistery in Ravenna decorated in the fifth century. Note the representation of the empty throne.

Limits of Interpretation and What is Our Share?

Linda Seidel in her Jan Van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait: Stories of an Icon (Cambridge University Press, 1993, p. 129) includes the following useful quotation to frame our consideration about how far our interpretation can go:

Few of us would disagree with the notion that viewers bring expectations of their own to an understanding of a work of art; few of us are likely to agree, however, about how little or how much autonomy a viewer enjoys in arriving at his or her own interpretation. For many, the range and nature of constraints on a given viewer's response are controversial matters. On one side are scholars, in the tradition of Panofsky, who limit the "beholder's share" by excluding from the interpretive process issues of daily life that inevitably attend it. Such individuals prefer to position art --its invention and appreciation-- above ordinary day-to-day encounters and to identify its sources and its purposes with what may be seen as privileged rather than prosaic claims. Audiences do not really matter much at all from this perspective. Other scholars, however, would argue that all meaning is lodged in a viewer's experience --though language- driven-- is not exclusively text-based, and that politics and sex have as much claim as religious or literary tracts in any interpretive strategy. Many scholars stand, knowingly or not, somewhere in between.

Silver Slipper Club by Johnathan Green

Jonathan Green's art documents the way of life, the traditions, and the customs of the now vanishing Gullah community of Gardens Corner, located north of Beaufort, South Carolina, where his grandmother raised him as a child. Gullah refers to a population of African Americans living on the South Carolina and Georgia Sea Islands. Relatively isolated from the larger population of the mainland of the United States, African Americans living on these islands preserved the language and customs of their West African heritage. The Silver Slipper Club captures a moment typical of a nightclub of the same name during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Although he did not witness the scene directly, Green had heard stories about the Silver Slipper Club. Green's choice of brightly colored and large-patterned clothing echoes the liveliness and enthusiasm of a room filled with people dancing and celebrating. In his color, style, and technique, Green shows us what it might be like to step in the Silver Slipper Club. In fact, because he does not individualize his figures with facial features, he makes the Gullah community seem more universal, and he invites us to be a part of the group. The Gullah are African Americans who live in the Lowcountry region of South Carolina and Georgia, which includes both the coastal plain and the Beaufort Sea Islands. The Gullah are known for preserving more of their African linguistic and cultural heritage than any other African-American community in the United States. They speak an English-based creole language containing many African loanwords and significant influences from African languages in grammar and sentence structure; Gullah storytelling, cuisine, music, folk beliefs, crafts, farming and fishing traditions, all exhibit strong influences from West and Central African cultures. The semi-tropical climate that made the Low country such an excellent place for rice production also made it vulnerable to the spread of malaria and yellow fever. While adhering to Christian doctrine, the Gullah practice a faith immersed in communal prayer, song, and dance. Many also continue to hold traditional African beliefs. Witchcraft, which they call wudu or juju, is one example that can be traced to the country of Angola. Some Gullah believe that witches can cast a spell by putting powerful herbs or roots under a person's pillow or at a place where he or she usually walks. There are also special individuals known as "Root Doctors" that serve to protect individuals from curses and witchcraft.

Today, the Gullah people still live and practice their lifestyle in the areas that were once home to their ancestors. Despite encroachment of modern American traditions and increased expansion into their homeland, these special people continue to provide an important glimpse into South Carolina's past.

Script found in GeeChee dialect: Cum fa jayn de Gullah/Geechee famlee een sum fun and ting fa de Holy Days! Satdee, December 3, 10 &17 from 10 am-5 pm een Marion Square Park een Chastun, SC gwine be “Gullah/Geechee Day.” Cum fa support de Gullah/Geechee bizness wha dey dey. Afta hunnuh dun shop een Chastun, mek hunnuh way doung and shop wid de famlee at de Martin Luther King Park pun St. Helena Island, SC Satdee, December 10 frum 9 am ta 2 pm. E gwine be de “Holiday Craft Fair.” So, hunnuh gwine wan git een dere. Ef hunnuh ain gwine nyam pun de fry fish dey or hunnuh wan mo Gullah/Geechee ting fa naym pun, hunnuh kin tek de famlee ta “MJ’s Soul Food” pun St. Helena fa a lil bit fa nyam pun and den shop sum mo een de Corners area stores or de Welcome Center at Penn Center while hunnuh dey dey. Cap off de ednin Satdee, December 10th at “Gullah Night on de Town” at de St. Helena Branch Library pun St. Helena Island, SC at 4 pm. Cum yeddi Delores Nevil sharin frum e book fa de chillun while de chillun wok pun sum holidee crafts and ting. Queen Quet, Chieftess of the Gullah/Geechee Nation (www.QueenQuet.com) gwine crak e teet wid de famlee bout how we celebrate de Holy Days de Gullah/Geechee Way! Hunnuh kin bring a dish fa de potluck meal we gwine nyam pun.

Gernica by Pablo Picasso "My whole life as an artist has been nothing more than a continuous struggle against reaction and the death of art. In the picture I am painting — which I shall call Guernica — I am expressing my horror of the military caste which is now plundering Spain into an ocean of misery and death." Pablo Picasso

Guernica (1937) by artist Pablo Picasso is one of the most famous paintings of all time. Like so many famous works of art, the meaning of Picasso's Guernica is not immediately clear and left wide open to analysis and interpretation. What is the meaning of Guernica, the mural by Pablo Picasso? A careful analysis and interpretation of the painting reveals the importance of Spain, war, and most of all bullfighting in Picasso's Guernica. Guernica was named after a small country town in north Spain that was the target of a terror bombing exercise by the German Luftwaffe during the Spanish Civil War.

As Picasso's quote suggests, Guernica is primarily a war painting, offering a visual account of the devastating and chaotic impact of war on both men and women, in this case specifically on civilian life and communities. Picasso completed the painting of Guernica in 1937, a time of widespread political unrest not just in Spain, but worldwide. World War II would begin just a couple years later and would further decimate the European continent as a whole. In Guernica, we see several victims of the bombing--some still living, some already dead. A figure sprawled supine in the foreground of the painting appears to be a corpse and is framed on both sides by living victims with their heads thrown back, wailing in agony. The figure to the left is a mother clutching a baby who appears to have died during the bombing.

The chaos caused by Europe's political instability is evident in Guernica's composition, with humans and animals jumbled together into a background of broken hard-edged geometric shapes, reminiscent of Cubism. The newspaper print background texture of the horse may also be a throwback to Picasso's early "Journal" Cubist artwork. While art critics enjoy analyzing the use of color in Picasso's "rose" or "blue" periods, in the mostly monochromatic painting Guernica the predominant "color" is mostly black, reminiscent perhaps of death itself. Picasso's Guernica is most likely influenced by another Spanish artist, Francisco de Goya, who often painted not only war paintings, but also bullfighting art. How does bullfighting influence the meaning of Picasso's Guernica? Guernica can be classified as a "war painting," but the painting also features many symbols--including a bull, horse, and a man with a sword--that would fit well into traditional bullfighting art, much like Picasso's own later art and sketches like Tauromaquia (1957). The bull is the unofficial national symbol of Spain, and bullfighting is a traditional pastime or spectacle sport in Spain, with this bullfighting symbolism connecting Guernica with a specifically nationalistic meaning. Rather than depicting a victorious matador bowing to the crowds before a slaughtered bull, in Guernica the bull remains stoically standing to the left side of the painting while the matador lays dead in the foreground, the sword or spear he might have used to slaughter the bull broken off in his hand. Like the fallen matador, his horse is also dying and anguished. Only the bull remains peaceful in Guernica, with the other figures and the entire composition of the painting turned toward the bull, an unlikely peaceful "center" for the war painting on the left side of the canvas. As the unofficial national symbol of Picasso's homeland and the most resilient figure in Guernica, the bull most likely is a symbol of Spain itself, the country still "standing" even after a brutal attack.

The colors of Guernica are black, white, and grey. It is an oil painting on canvas, measuring 11 feet tall by 25.6 feet wide, and is on display at the Museo Reina Sofía (Spain’s national museum) in Madrid. The work of art was completed by Picasso in June, 1937 and depicts turmoil, people and animals suffering, with buildings in disarray – torn apart by violence and mayhem. Guernica can be summarized by its individual components as follows: The encompassing scenario is set within a room where, in an empty part on the left, a wide-eyed bull looms above a woman grieving for a dead child she is holding. The middle of the painting shows a horse falling over in pain, having been pierced by a spear or lance. It is essential to bear in mind that the gaping wound in the side of the horse is the primary focus of the artwork. Two obscured visuals formed by the horse can be found in Guernica: first is human skull is superimposed on the body of the horse. Secondly, it appears that a bull is goring the horse from below. The head of the bull is formed largely by the front leg of the horse, which has its knee on the ground. The knee cap of the horse makes up the bull’s nose, and the bull’s horn jabs at the horse’s breast. The tail of the bull is formed in the shape of flame and smoke appearing in the window at far left, produced by a lighter shade of grey bordering it. Underneath the horse lies a dead mutilated soldier, the hand of his severed arm still grasping a broken sword, from which a flower springs up. In the open palm of the dead soldier is a stigmata, symbolic of the sacrifices of Jesus Christ. Above the head of the impaled horse is a light bulb which glares outward like an evil eye, it can also be likened to the single bulb hanging in a prison cell. Picasso may have also intended the symbolism of the bulb to be associated with the Spanish word for light bulb which is “bombilla”. This brings to mind the word “bomb”, which could symbolize the detrimental impact which technology can have on humanity. Towards the upper right of the horse is a fearful female figure that appears to be watching the actions in front of her. She seems to have floated through a window into the room. Her floating arm is holding a flaming lamp and the lamp is very close to the bulb, symbolizing hope – and is in opposition to the light bulb. Staggering in from the right, below the floating female figure, is a horror-struck woman who looks up vacantly into the glaring light bulb. The tongues of the grieving woman, the bull, and the horse are shaped like daggers, which suggest screaming. A bird, probably a dove, is perched on a shelf behind the bull and seems to be in panic. On the far right of the painting, a person with arms extended in sheer terror is trapped by fire from below and above. A shadowy wall that has an open door becomes the right end of the painting. Interpretations Interpretations of the symbolism of Guernica fluctuate extensively and contradict each other depending on the viewer. The list below echoes the most common interpretations and opinions of historians: The form and bearing of the figures in Guernica convey protest. The artist utilizes white, black, and grey paint to create a sorrowful atmosphere and convey suffering and disorder. The flaming structures and crumbling walls do not merely communicate the devastation of Guernica, but reveal the harmful force of war. The newspaper print used in the backdrop of the painting portrays how Picasso found out about the bombing. The light bulb in the artwork symbolizes God’s watchful eye. The broken sword close to the base of the painting signifies the defeat of the people by their conquerors. With Guernica, Picasso wanted to establish his identity and his strength as an artist when confronted with political authority and intolerable violence. But instead of being simply a political piece of art, Guernica ought to be viewed as Picasso’s statement on what art can in fact donate to the self-assertion that emancipates all humanity, and shields every person from overpowering forces like political crime, war, and death.

ANOTHER STAGE OF GUERNICA INVOLVED COLOR. Guernica is one of history’s most recognizable grayscale paintings, but at one point during the piece’s development, Picasso entertained the idea of adding color to the project. He included a red teardrop sprouting from a crying woman’s eye, as well as swatches of colored wallpaper. None of these elements made the final cut. THE PAINTING INSPIRED A PICASSO EXCHANGE WITH A GESTAPO OFFICER. Almost as famous for his biting wit as he was for his artistic prowess, Picasso once treated a German Gestapo officer to a sharp rejoinder in reference to the painting’s depiction of the atrocities of fascism and war. When asked by an officer about a photo of the painting, “Did you do that?” Picasso is said to have replied, “No, you did.”