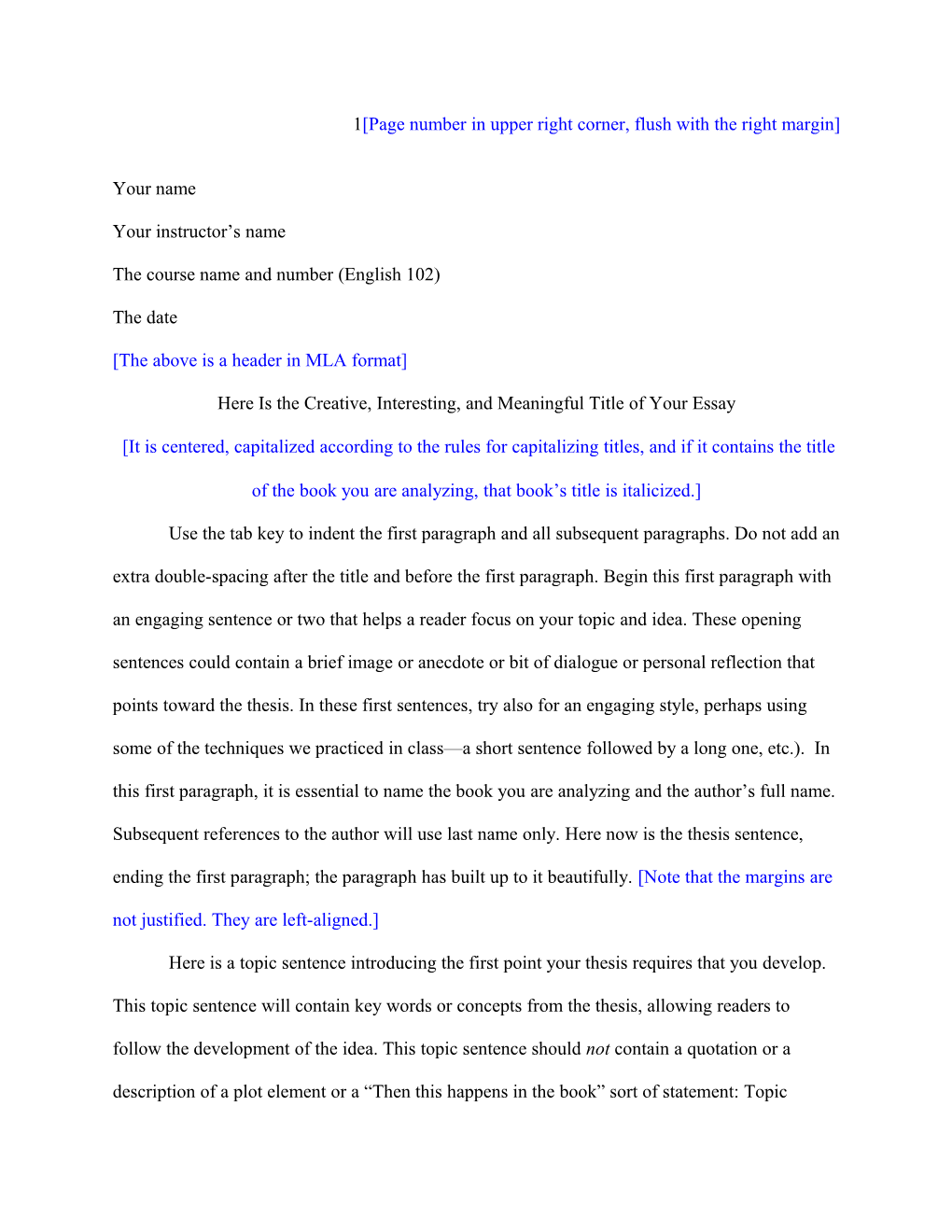

1[Page number in upper right corner, flush with the right margin]

Your name

Your instructor’s name

The course name and number (English 102)

The date

[The above is a header in MLA format]

Here Is the Creative, Interesting, and Meaningful Title of Your Essay

[It is centered, capitalized according to the rules for capitalizing titles, and if it contains the title

of the book you are analyzing, that book’s title is italicized.]

Use the tab key to indent the first paragraph and all subsequent paragraphs. Do not add an extra double-spacing after the title and before the first paragraph. Begin this first paragraph with an engaging sentence or two that helps a reader focus on your topic and idea. These opening sentences could contain a brief image or anecdote or bit of dialogue or personal reflection that points toward the thesis. In these first sentences, try also for an engaging style, perhaps using some of the techniques we practiced in class—a short sentence followed by a long one, etc.). In this first paragraph, it is essential to name the book you are analyzing and the author’s full name.

Subsequent references to the author will use last name only. Here now is the thesis sentence, ending the first paragraph; the paragraph has built up to it beautifully. [Note that the margins are not justified. They are left-aligned.]

Here is a topic sentence introducing the first point your thesis requires that you develop.

This topic sentence will contain key words or concepts from the thesis, allowing readers to follow the development of the idea. This topic sentence should not contain a quotation or a description of a plot element or a “Then this happens in the book” sort of statement: Topic 2[Page number in upper right corner, flush with the right margin] sentences tell us what the paragraph is going to be about. Though they might set a reader up for receiving illustrations and evidence from the text, they don’t contain that evidence. After this topic sentence, the paragraph illustrates its point with examples / illustrations / quotations / paraphrases from the text. It introduces each of these examples clearly, showing how it connects to the point in the topic sentence. Include parenthetical page citations (Tenenbaum 100) for all references to the text—not just quotations, but also summary and paraphrase. After every quotation or reference to the text are several sentences of your own explanations and analysis:

What do you make of this example? How does it illustrate the specific point in the paragraph’s topic sentence? Explain your reasoning. Avoid simply repeating in your own words what the text reference already says. Sometimes these interpretations and explanations are blended into the sentences with the references to the text. Now we come to the end of the paragraph. If it has been very long and detailed, it might need a brief recap of its overall point. But if it’s a short paragraph, it won’t need that. Consider whether you need a sentence that bridges to the next paragraph.

The next paragraph begins with some sort of clear transition, or bridge, from the previous paragraph. Here are examples of useful bridge phrases: “Another example of ______is…”; “The above point is confirmed by…”; “An additional way of looking at it might be…”;

“’The second instance of this is….” After this bridging element, introduce the topic, or point of this paragraph. As with the topic sentence in the above paragraph, this one develops another aspect of the thesis, whichever one follows logically from the previous point. As with the above paragraph, after the topic, or point, come the illustrations from the text and your interpretations, analysis, exploration. Be very clear about how the example connects to the thesis. Show all the 3[Page number in upper right corner, flush with the right margin] steps of your thinking. As before, close with a recap or with an anticipation of the next paragraph.

Most paragraphs of the essay will follow the structure discussed in the meta-paragraphs; however, you might have a one-sentence paragraph now and then for making important transitions or for highlighting main points.

This paragraph illustrates how a long quotation is formatted. Your paper will mainly use short quotations so that not too many points or examples are introduced in any one chunk.

However, occasionally (perhaps once in this five-page essay) you might need to quote a slightly longer passage to fully illustrate your point. When a quotation is longer than four typed lines

(your typing, not the original book’s typing), use block format. Now here is the sentence that introduces the quotation—it contains a complete idea of your own and shows to the reader what you want them to look for in the quote presented after this colon:

This long quote is indented double the distance of a regular paragraph, so that it is

easy to distinguish. After I type it, I select it and move it to its properly indented

spot using the ruler at the top of my Word program. It is not surrounded by

quotation marks because the extra indenting alerts the reader to the fact that it is a

quotation. Because the text I’m quoting ends with a period, I’m ending this

quotation with a period. After the period comes the parenthetical page citation,

and there is no period after it. (Tenenbaum 1000)

Now in the same paragraph as that quotation include whatever analysis and explanation you need to. It’s important to have a lot to say in order to justify having such a long quotation taking up space in the paper. 4[Page number in upper right corner, flush with the right margin] As usual, here’s the transitional bridge from the previous paragraph and the topic sentence of this paragraph. This paragraph is going to refer to the required second source. The information from that source is going to help explain something about the book you’re analyzing. It will support some point or sub-point of the thesis, allowing you, perhaps, to interpret a passage more deeply. Let’s say, for example, the paper is talking about the symbolism of X in the book, and you’ve found a great scholarly article about the history of X as a symbol.

Here’s a sentence introducing the information from that source: According to

______, the author of “Article Title,” X has in the past symbolized [here’s a paraphrase or summary of what the article says X has symbolized] (page). In addition, [the author] explains that [here’s some more paraphrase and summary from the article] (page). The idea that __[something from that article]__(page) helps us see that _[connect to your own ideas about the symbolism of X in the book you’re analyzing]. Of course, the full citation for this article will be found on the works cited page, where the author’s name, last name first, in alphabetical order, will be easy to find as a reader scrolls down the hanging indent by the left margin.

Here follow several more paragraphs developing various points and sub-points of the thesis, and all these paragraphs use the structure shown above: Point, Illustration, Explanation, including any necessary transitions and bridge sentences. I will not write all of these paragraphs since this is a meta-paper and not a real one.

If the reader has been following along, at this point they probably have some questions, arguments, or alternative interpretations. This would be a good place to anticipate a reader’s objections or alternative readings and to respond to them. Show why my interpretations are apt.

Or accept that this imaginary reader might have a valid point. Perhaps that point needs to be 5[Page number in upper right corner, flush with the right margin] incorporated into the thesis in some way—maybe you can adjust it with some ifs or maybes or other qualifications.

Now, nearing the end of the essay, it’s time to present the thesis in all of its full complication. At the very beginning of this essay, the reader wasn’t ready for the full and complex version of my thesis, with all its exceptions and implications; but now, after this wonderful analysis, after you’ve explained all the steps of your thinking, they will be able to understand a very complicated idea. So here it is: It’s not a re-statement, but a fuller statement. If at this point you’re simply restating your original thesis in the same words as before, that may mean that the essay hasn’t gone anywhere; the idea hasn’t developed. In that case, perhaps the original thesis was not of the right scope or focus for this essay.

Now I’m ready to end my essay. I want to give the reader ways to take the idea further, to perhaps use it in their personal lives or in the ways they think about the world. I want my analysis to affect them emotionally. So I’m going to try to extend my idea: How does my thesis relate to the world outside the book? How might the reader apply this idea to other topics? If I have a personal reflection about the ideas in this essay, I can add it here. A nice touch also is to include an image or other reference to something in the title or first paragraph, so that the essay not only extends outward but also makes a complete circle with itself. But wait, the essay’s not over! Scroll beyond the page break below to see the works cited page. 6[Page number in upper right corner, flush with the right margin] Works Cited

[Centered, capitalized]

This is pretending to be a works cited entry. The works cited entries are organized by last name

of the author. If there is no author named, list it alphabetically by title.

Each entry uses a hanging indent. There are no extra spaces between the entries. Just continue

the regular double-spacing. Your works cited page for this essay will have two entries,

one for Crescent and the other for your additional source.

[I am not creating those entries for you here. Find the correct format by looking at the OWL

Purdue website, and if you can’t find the right format, ask me to help you.]