2011 Christchurch earthquake From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 2011 Christchurch earthquake

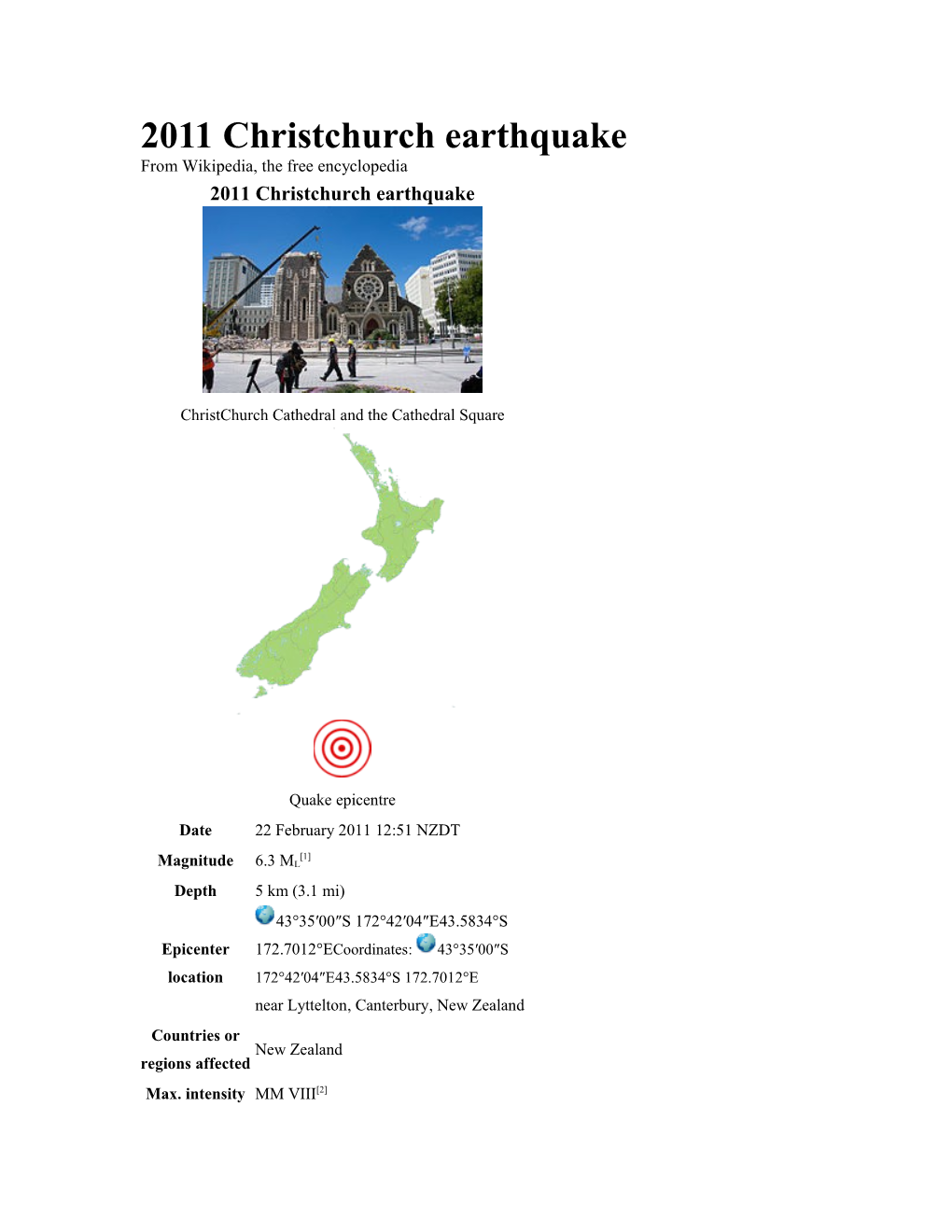

ChristChurch Cathedral and the Cathedral Square

Quake epicentre Date 22 February 2011 12:51 NZDT

[1] Magnitude 6.3 ML Depth 5 km (3.1 mi) 43°35′00″S 172°42′04″E43.5834°S Epicenter 172.7012°ECoordinates: 43°35′00″S location 172°42′04″E43.5834°S 172.7012°E near Lyttelton, Canterbury, New Zealand Countries or New Zealand regions affected Max. intensity MM VIII[2] Peak ground 1.88g (city); 2.2g (epicentre)[3] acceleration 3.5 m (11 ft) tsunami waves in Tasman Tsunami Lake, following quake-triggered glacier calving from Tasman Glacier[4][5] 166 confirmed dead (7 March)[6][7] Casualties About 200 missing (7 March)[7] 1500–2000 injured, 164 seriously[8]

The 2011 Christchurch earthquake (also known as the 2011 Canterbury earthquake and the Lyttelton earthquake) was a 6.3-magnitude earthquake[1] that struck the Canterbury region in New Zealand's South Island at 12:51 pm on 22 February 2011 local time (23:51 21 February UTC),[1][9] causing widespread damage and multiple fatalities. The earthquake was centred 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) west of the town of Lyttelton, and 10 kilometres (6 mi) south-east of the centre of Christchurch, New Zealand's second-most populous city.[1] It followed nearly six months after the 7.1 magnitude 2010 Canterbury earthquake that caused significant damage to the region but no direct fatalities.

At least 166 people have been confirmed dead as of 7 March 2011,[6][7] with the final death toll expected to be over 200,[10] making the earthquake the second-deadliest natural disaster recorded in New Zealand (after the 1931 Hawke's Bay earthquake). Prime Minister John Key stated that 22 February "may well be New Zealand's darkest day". Nationals from more than 20 countries are among those missing.[11] The New Zealand Government declared a national state of emergency.

JPMorgan Chase & Co investment analysts estimated that the earthquake could cost insurers US$12 billion (NZ$16 billion[12]).[13]

.

Geology Earthquake intensity map

The 6.3 quake was part of a series of earthquakes and aftershocks in the region following the 7.1-magnitude 4 September 2010 Canterbury earthquake. While New Zealand's GNS Science describe it as "technically an aftershock" of the earlier event, other seismologists, including those from USA and Geoscience Australia, consider it a separate event, given its location on a separate fault system.[14][15] It occurred on a single faultline, which appears to have no underground connection to the four-part Greendale fault responsible for the September quake.[16] It has generated a significant series of its own aftershocks, many of which are considered big for a 6.3 quake.[17] Over 200 aftershocks were experienced in the first week, the largest measuring magnitude 5.9, occurring just under 2 hours after the main shock.[18]

Initial reports suggest the earthquake occurred at a depth of 5 kilometres (3 mi); further analysis of seismic data might result in a revision of that depth.[17] Early reports suggested that it occurred on a previously unknown faultline running 17 km east-west from Taylor's Mistake to Halswell, at depths of 3–12 km,[19] but the Institute of Professional Engineers have since stated that "GNS Science believe that the earthquake arose from the rupture of an 8 x 8 km fault running east-northeast at a depth of 1-2 km depth beneath the southern edge of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary and dipping southwards at an angle of about 65 degrees from the horizontal beneath the Port Hills.[20] Although the rupture was subsurface (ie. did not break the surface), satellite images indicate the net displacement of the land south of the fault was 50 cm westwards and upwards; the land movement would have been greater during the quake.[16] Land movement is varied around the area horizontally - in both east and west directions - and vertically; the Port Hills have been raised by 40 cm.[21]

The quake was a "strike-slip event with oblique motion" - mostly horizontal movement with some vertical movement - [22] with reverse thrust (ie. vertical movement upwards).[3] The vertical acceleration was far greater than the horizontal acceleration.[22] The intensity felt in Christchurch was MM VIII.[2] The peak ground acceleration (PGA) in the Christchurch area exceeded 1.8g (i.e. 1.8 times the acceleration of gravity),[23] with the highest recording 2.2g, at Heathcote Valley Primary School,[3] a shaking intensity equivalent to MM X+.[24] This is the highest PGA ever recorded in New Zealand; the highest reading during the September 2010 event was 1.26g, recorded near Darfield.[23] The PGA is also one of the greatest ever recorded in the world,[25] and was unusually high for a 6.3 quake.[17] The central business district (CBD) experienced PGAs in the range of [26] 0.574 and 0.802 g. In contrast, the 7.0 Mw 2010 Haiti earthquake had an estimated PGA of 0.5g.[25] The acceleration occurred mainly in a vertical direction,[22] with eyewitness accounts of people being tossed into the air.[25] The force of the quake was "statistically unlikely" to occur more than once in 1000 years, according to one seismic engineer, with a PGA greater than many modern buildings were designed to withstand.[27] New Zealand building codes require a building with a 50-year design life to withstand predicted loads of a 500-year event; initial reports by GNS Science suggest ground motion "considerably exceeded even 2500-year design motions”.[28] By comparison, the 2010 quake - in which damage was predominately to pre-1970s buildings - exerted 65% of the design loading on buildings.[27] The acceleration experienced in February 2011 would "totally flatten" most world cities, causing massive loss of life; in Christchurch, New Zealand's stringent building codes limited the disaster.[15]

It is also likely that "seismic lensing" contributed to the ground effect, with the seismic waves rebounding off the hard basalt of the Port Hills back into the city.[19] Geologists reported liquefaction was worse than the 2010 quake.[22] The quake also caused significant landslips and rockfalls on the Port Hills.[22]

Although smaller in magnitude than the 2010 quake, the earthquake was more damaging and deadly for a number of reasons. The epicentre was closer to Christchurch, and shallower at 5 kilometres (3 mi) underground, whereas the September quake was measured at 10 kilometres (6 mi) deep. The February earthquake occurred during lunchtime on a weekday when the CBD was busy, and many buildings were already weakened from the previous quakes.[29][30] The PGA was extremely high, and simultaneous vertical and horizontal ground movement was "almost impossible" for buildings to survive intact.[22] Liquefaction was significantly greater than that of the 2010 quake, which required the removal of over 30,000 tonnes.[31] By 4 March, over 218,000 tonnes had been removed following the 22 February event, with an estimated 60,000 tonnes remaining.[32] The increased liquefaction caused significant ground movement, undermining many foundations and destroying infrastructure, damage which "may be the greatest ever recorded anywhere in a modern city".[20]

While both the 2010 and 2011 earthquakes occurred on "blind" or unknown faults, New Zealand's Earthquake Commission had, in a 1991 report, predicted moderate earthquakes in Canterbury with the likelihood of associated liquefaction.[15][33] Emergency management In the immediate moments following the quake, rescue and response was offered by ordinary citizens and those emergency services on duty. Although communication was initially difficult, and it took many hours for a full picture of the devastation to be obtained, a full emergency management structure was in place within two hours, with national coordination operated from the National Crisis Management Centre bunker in the Beehive in Wellington.[34] Regional emergency operations command was established in the Christchurch Art Gallery, a modern earthquake-proofed building in the centre of the city which had sustained only minor damage.[35] As per the protocols of New Zealand's Coordinated Incident Management System and the Civil Defence Emergency Management Act, the Civil Defence became lead agency, with - John Hamilton as National Controller - supported by New Zealand Police, Fire Service, Defence Force and many other agencies and organisations.[36] One experienced international USAR team member described the response as "the best-organised emergency" he had witnessed.[37] On 23 February the Minister of Civil Defence, John Carter declared the situation a national state of emergency,[38] the country's first for a civil defence emergency (the only other one was for the 1951 waterfront dispute).[39]

The Government response was immediate and significant, with many departments and ministries involved. Cabinet Minister Gerry Brownlee 's regular portfolios were distributed amongst other cabinet ministers, so he could focus solely on earthquake recovery.[40] After a brief sitting, when a National Emergency was declared, Parliament was adjourned until 8 March so cabinet could work on earthquake recovery.[41] Prime Minister John Key and other ministers regularly visited Christchurch, supporting Christchurch mayor Bob Parker, who was heavily involved in the emergency management and became the face of the city, despite his own injuries and family concerns.[42]

Police

Christchurch Police were supplemented by staff and resources from around the country, along with a 300-strong contingent of Australian Police, who were sworn in as New Zealand Police on their arrival, bringing the total officers in the city to 1200.[43] Alongside their regular policing duties, Police provided security cordons, organised evacuations, supported search and rescue teams, missing persons and family liaison, and organised media briefings and tours of the affected areas. They also provided forensic analysis and evidence gathering at fatalities,and Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) teams, working closely with pathologists, forensic dentists and scientists, and the coroner at the emergency mortuary established at Burnham Military Camp.[44] They were aided by DVI teams from Australia, UK, Thailand[45] Taiwan and Israel.[44] They follow international best practice for victim identification after disasters - which is extremely thorough to insure correct identification - and have assistance from the Interpol DVI chair.[46][47]

New Zealand Police requested 300 police from Australia for non-rescue tasks such as traffic control, general policing duties and to prevent looting. The contingent was formed by 200 from the New South Wales Police Force,[48] 50 from the Australian Federal Police[49] and others from Queensland, Victoria and South Australia state police forces.[50] In total, 323 Australian police, including DVI officers, were sent.[51][52] Following their arrival on 25 February, they were briefed on New Zealand law and procedure and the emergency regulations before being sworn in with New Zealand policing powers.[50] Many of them received standing ovations from appreciative locals as they walked through Christchurch Airport upon arrival.[53] While serving in New Zealand, the Australian officers would not carry guns, since New Zealand police are a routinely unarmed force; the officers would instead be equipped with standard New Zealand issue batons and capsicum spray.[53][54] It was the first time large numbers of Australian police have assisted in New Zealand.[52]

Search and rescue

A Japanese search and rescue team approaches the ruins of the CTV building.

The New Zealand Fire Service coordinated search and rescue, particularly the Urban Search and Rescue (USAR) teams from New Zealand and Australia, UK, USA, Japan, Taiwan, China and Singapore, totalling 150 personnel from New Zealand and 429 from overseas.[37] They also responded to fires, serious structural damage reports, and land slips working with structural engineers, seismologists and geologists, as well as construction workers, crane and digger operators and demolition experts.

A team of 72 urban search and rescue specialists from New South Wales, Australia was sent to Christchurch on a RAAF C-130 Hercules, arriving 12 hours after the quake, with another team of 70 (along with three sniffer dogs) from Queensland sent the following day.[55] A team of 55 Urban Search and Rescue from the Singapore Civil Defence Force were sent.[56] The United States sent Urban Search and Rescue California Task Force 2, a 74-member heavy rescue team consisting of firefighters and paramedics from the Los Angeles County Fire Department, doctors, engineers and 26 tons of pre-packaged rescue equipment.[57][58] Japan sent 70 search-and-rescue personnel including specialists from the coastguard, police and fire fighting service, as well as three sniffer dogs.[59] The United Kingdom sent a 53 strong search and rescue team including 9 Welsh firefighters who had assisted the rescue effort during the 2010 Haiti Earthquake.[60] Taiwan sent a 22-member team from the National Fire Agency, along with 2 tons of specialist search and rescue equipment.[61][62] China sent a 10-member specialist rescue team.[63]

Defence forces The New Zealand Defence Force - staging their largest operation on New Zealand soil[64]- provided logistics, equipment, transport, airbridges, evacuations, supply and equipment shipments, survey of the Port and harbour, and support to the agencies, including meals; they assisted the Police with security, and provided humanitarian aid particularly to Lyttleton, which was isolated from the city in the first days. [65] Over 1400 Army, Navy and Air Force personnel were involved,[66] and Territorials (Army Reserve) were called up.[67] They were supplemented by 116 soldiers from the Singapore Army, in Christchurch for a training exercise at the time of the earthquake, who assisted in the cordon of the city.[56][68]

The Royal New Zealand Air Force provided an air bridge between Christchurch and Wellington using a Boeing 757 and two C-130 Hercules, bringing in emergency crews and equipment and evacuating North Island residents and tourists out of Christchurch. The crew of the Navy ship Canterbury, in Lyttelton harbour at the time of the earthquake, provided meals for 1,000 people left homeless in that town,[citation needed] and accommodation for a small number of locals.[69] The Royal Australian Air Force also assisted with air lifts. On one of their journeys, a RAAF Hercules sustained minor damage in an aftershock.[70]

The army also operated desalination plants to provide water to the eastern suburbs.[71]

Medical response

St John Ambulance provided and coordinated emergency medical response, and triage stations immediately following the quake, as well as medics to support USAR teams. The Canterbury District Health Board coordinated health and medical support across the city, cancelling elective surgery and outpatients, and evacuating existing patients from the hospitals to other centres to increase capacity. They managed primary care facilities (pharmacies and general practice) to ensure city-wide coverage, and organised evacuations from damaged aged care and disabled care facilities to other regions. They were supported by medical staff from around New Zealand, and Australia, particularly the Australian field hospital brought in within days. Public Health issues (such as contamination and infection control) were also managed by the Health Board.

Australia's foreign minister Kevin Rudd told Sky News that New Zealand's Foreign Affairs Minister Murray McCully had asked for further help from Australia. He said Australia was also sending counsellors over and a disaster medical assistance team comprising 23 emergency and surgical personnel.[72] A field hospital providing 75 beds arrived 24 February.[55] Set up in the badly-affected eastern suburbs, it was equipped to provide triage, emergency care, maternity, dentistry and isolation tents for gastroenteritis, and also provide primary care since most general practices in the area were unable to open.[73]

Humanitarian and welfare Humanitarian support and welfare were provided by various agencies, in particular the New Zealand Red Cross and the Salvation Army. Welfare Centres and support networks were established throughout the city. Government Departments, such as WINZ and Housing New Zealand established contact with as many people as possible and provided grants and assistance. Many church and community-led projects also became established. The scale of the disaster meant many people went some days without official contact, so neighbourhoods and streets were encouraged to attend to those around them. Official visitation teams were organised by Civil Defence, with aim of visiting every household; the teams, which assessed homes and welfare needs, and passed on official information, included structural engineers or assessors from EQC. LandSAR assisted with the patrols. [74]

Infrastructures and support

Businesses and organisations contributed massively to the initial rescue, recovery and emergency infrastructure. Orion, Christchurch's electricity company, assisted by other companies from New Zealand worked constantly to restore power, including the erection of new over head lines to get power into the eastern suburbs; within a week power had been restored to 85% households. Generators were donated, and telephone companies established emergency communications and free calls. Water provision was worked on by companies and contractors, while Fonterra provided milk tankers to bring in water. Waste water and sewerage systems had been severely damaged, so households had to establish emergency latrines. Chemical toilets and portaloos from throughout New Zealand were brought in, with thousands more freighted from Australia and USA. Many companies assisted with transport, particularly Air New Zealand, who operated extra flights of Boeing 747 aircraft to/from Auckland and Boeing 737/Airbus A320/Boeing 777 aircraft to/from Wellington to move people and supplies in and out of Christchurch. The airline also offered flights to and from Christchurch for NZ$ 50 one way from any New Zealand, Australian and Pacific Island Airport, for Christchurch residents, and NZ$400 one way from other international destinations for affected family members.[75]

Fundraising and support efforts were established throughout the country, with many individuals, community groups and companies providing food and services to the city, for welfare and clean up. Many impromptu initiatives gained significant traction. Thousands of people helped with the cleanup efforts - involving the removal of over 200,000 tonnes of liquefaction silt - including Canterbury University's Student Volunteer Army (created after the September quake but significantly enlarged) and the Federated Farmers' "Farmy Army".[76] The "Rangiora Earthquake Express" provided over 250 tonnes of water, medical supplies, and food - including hot meals - from nearby Rangiora by helicopter and truck.[77] Casualties, damage, and other effects The effect of liquefaction in North New Brighton, Christchurch

As of 7 March, 166 people were confirmed dead in the quake.[6] While the list of missing likely includes many of those confirmed dead, 240 remain unaccounted for;[78] a figure that has not changed greatly since 24 February.[79] Police have expected the final death toll to be over 200.[10] More than 100 people may have been lost in the Canterbury Television building alone.[80] Due to the injuries sustained by some individuals, it is possible some bodies might remain unidentified, meaning that the exact death toll may never be known.[81] Between 1500 and 2000 people have been treated for minor injuries, and Christchurch Hospital alone has treated 220 major trauma cases connected to the quake.[82]

Results of liquefaction, after soil resolidifies

Rescue efforts continued for over a week, then shifted into recovery mode. The last survivor was pulled from the rubble the day after the quake.[83]

At 5 pm local time on the day of the earthquake, Radio New Zealand reported that 80% of the city had no power. Water and wastewater services have been disrupted throughout the city, with authorities urging residents to conserve water and collect rainwater. It is expected that the State of Emergency Level 3, the highest possible in a regional disaster, would last for at least five days. Medical staff from the army were deployed. Road and bridge damage occurred and hampered rescue efforts.[84] Soil liquefaction and surface flooding also occurred.[85] Road surfaces were forced up by liquefaction, and water and sand were spewing out of cracks.[86] A number of cars were crushed by falling debris.[87] In the central city, two buses were crushed by falling buildings.[88] As the earthquake hit at the lunch hour, some people on the pavements were buried by collapsed buildings.[89]

Buildings affected

ChristChurch Cathedral shortly after the 6.3-magnitude earthquake, and before the second aftershock

Buildings collapsed around Cathedral Square in central Christchurch. By the afternoon of March 3, of the 3,000 inspected buildings within the Four Avenues of the central city, 45% had been given red or yellow stickers to restrict access because of the safety problems. Many heritage buildings were given red stickers after inspections.[90] ChristChurch Cathedral lost its spire.[91][92] The spire's tip had also fallen in earthquakes in 1888 and 1901,[93] but much more fell during the 22 February earthquake. Although police initially believed up to 22 people died in the collapse of the cathedral's tower, a thorough search of the rubble confirmed no fatalities occurred there.[80][94]

Christchurch Hospital was partly evacuated due to damage in some areas,[95] but remained open throughout to treat the injured. The New Zealand defence forces were called in to assist in evacuating the central business district.[96]

The six-storey Canterbury Television (CTV) building collapsed leaving only its lift shaft standing, which caught fire. The building housed the TV station, a medical clinic and an English language school. The school - King's Education - catered to students from Japan, China, the Philippines, Thailand, Saudi Arabia, Taiwan, and Korea.[97] On 23 February, police decided that the damage was not survivable, and rescue efforts at the building were suspended. More than 100 people may have died in the building. Fire-fighting and recovery operations resumed that night,[98] later joined by a Japanese search and rescue squad. Thirteen Japanese students from the Toyama College of Foreign Languages are missing, with some feared trapped in the rubble.[99][100] 47 bodies have been recovered from the CTV building.[101]

A collapsed fish and chip shop in New Brighton, Christchurch.

The six-storey PGC House[102] on Cambridge Terrace, headquarters of Pyne Gould Corporation, collapsed, and thirty of the building's two hundred workers were still believed to be trapped within as night fell. On Wednesday morning, 22 hours after the quake, a survivor was pulled from the rubble.[103] The reinforced concrete building had been constructed in 1963–64.[104]

On 28 February 2011, the Prime Minister announced that there would be an inquiry into the collapse of buildings that had been signed off as safe after the 4 September earthquake "to provide answers to people about why so many people lost their lives."[105] [106]

On 23 February, Hotel Grand Chancellor, Christchurch's tallest hotel, was reported to be on the verge of collapse.[107] The 26-storey building was displaced by half a metre in the quake and had dropped by 1 metre on one side. The building was thought to be irreparably damaged and have the potential to bring down other buildings if it falls. An area of a two-block radius had been cleared around the hotel.[108][109] As of 7 March, the building has been stabilised, but debate is still continuing about exactly what will happen to the Hotel Grand Chancellor, though it is generally considered that the building will be brought down in a controlled manner so that further work can be done with the buildings nearby, which were cordoned off due to the likelihood of collapse of the hotel.[110]

Oxford Terrace Baptist Church was one of many churches damaged by the quake. The historic Canterbury Provincial Council Buildings were severely damaged, with the Stone Chamber completely collapsing.[30][111]

The Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament was also severely damaged with the towers falling and a decision made to remove the dome because the supporting structure was weakened.[112][113] Several other churches have been seriously damaged, including: Knox Presbyterian Church, St Luke's Anglican Church, Durham Street Methodist Church, St Paul's-Trinity-Pacific Presbyterian Church, Oxford Terrace Baptist Church and Holy Trinity, Lyttelton. Sydenham Heritage Church and the Beckenham Baptist Church were heavily damaged and then demolished days after the earthquake.[114] Concrete block construction fared badly, leaving many modern iconic buildings damaged.[115]

Suburbs

On 7 March, Prime Minister John Key said that around 10,000 houses would need to be demolished, and liquefaction damage meant that some parts of Christchurch could not be rebuilt on.[116]

Lyttelton

Buildings in Lyttelton sustained widespread damage, with a fire officer reporting that 60% of the buildings in the main street had been severely damaged.[117] No lives were believed to be lost in the town,[118] but two people died on local walking tracks after being hit by rockfalls.[119] The town's historic Timeball Station was extensively damaged, adding to damage from the preceding earthquake in September 2010. The New Zealand Historic Places Trust is planning to dismantle it, with the possibility of reconstruction.[120]

Sumner

Landslides occurred in Sumner, crushing buildings.[121][122] Parts of Sumner were evacuated during the night of 22 February after cracks were noticed on a nearby hillside. [123] Three deaths were reported in the Sumner area, according to the Sumner Chief Fire Officer.[124] The Shag Rock, a notable landmark, was reduced to half of its former height. [125]

Redcliffs

In contrast to the September 2010 earthquake, Redcliffs and the surrounding hills suffered severe damage. The cliff behind Redcliffs School collapsed on to the houses below.[126]. Large boulders were found on the lawns of damaged houses.[127]

Twelve streets in Redcliffs were evacuated on Thursday night (24 February) after the cliffs and hills surrounding Redcliffs were deemed unstable.[128] Residents were allowed back on Monday night (28 February).[129]

Beyond Christchurch Around 30 million tonnes (33 ST) of ice tumbled off the Tasman Glacier into the Tasman Lake, some 200 kilometres (120 mi) from the epicentre, hitting tour boats with tsunami waves 3.5 metres (11 ft) high.[130]

By the evening of 22 February, KiwiRail reported that the TranzAlpine service was terminating at Greymouth and the TranzCoastal terminating at Picton.[85] These two services were cancelled until 4 March, to allow for personnel resources to be transferred to repairing track and related infrastructure, and moving essential freight into Christchurch.[131] KiwiRail also delayed the 14 March departure of its Interislander ferry Aratere to Singapore for a 30-metre extension and refit prior to the 2011 Rugby World Cup. With extra passenger and freight movements over Cook Strait following the earthquake, the company wouldn't be able to cope with just two ships operating on a reduced schedule too soon after the earthquake, so pushed back the departure to the end of April.[132]

New Zealand and American research operations in Antarctica have been badly affected by the earthquake, which occurred close to the end of the summer season. Christchurch acts as the major supply and transportation base for both Scott Base and McMurdo Sound research stations, and would normally be the initial destination for scientists returning from the summer season (the bases operate with reduced numbers in the dark Antarctic winter). The problems are exacerbated by the unusual break-up of sheet ice which is normally used for runways in the Antarctic.[133] The earthquake was felt as far away as Scott Base.[134] Several researchers linked to US Antarctic Research are among those missing in Christchurch as a result of the earthquake.[135]

The quake was felt as far north as Tauranga[136] and as far south as Invercargill, where the 111 emergency network was rendered out of service.[137]

Owners and pets

Animal welfare agencies reported that many pets were lost or distressed following the earthquake.[138][139] SPCA rescue manager Blair Hillyard said his 12-strong team assisted urban search and rescue teams that encountered aggressive dogs while conducting house- to-house checks. The team also worked with animals in areas where humans had been evacuated and distributed animal food and veterinary supplies to families in need.

Hillyard said that the situation for animals had been "deteriorating because of time issues" and was forcing concerned animal owners to break through police cordons to search for their pets. "That is really one of the common problems of why people break the cordon. It's not to go and do burglaries ... it's to go and retrieve their pets."[140] Response

On the day of the quake, Prime Minister John Key said that 22 February "may well be New Zealand's darkest day",[141] and Mayor of Christchurch Bob Parker warned that New Zealanders are "going to be presented with statistics that are going to be bleak".[142] Key also stated that "All Civil Defence procedures have now been activated; the Civil Defence bunker at parliament is in operation here in Wellington."[143] The New Zealand Red Cross launched an appeal to raise funds to help victims.[144]

New Zealand's monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, issued a statement on the disaster, saying she was "utterly shocked" and her "thoughts were with all those affected".[145] Her son and heir to the New Zealand throne, Prince Charles, also said to New Zealand's governor- general and prime minister: "My wife and I were horrified when we heard the news early this morning... The scale of the destruction all but defies belief when we can appreciate only too well how difficult it must have been struggling to come to terms with last year's horror... Our deepest sympathy and constant thoughts are with you and all New Zealanders."[146] Other members of the Royal Family signed the condolence book at New Zealand House in London.[147][148]

RNZAF aerial survey of damage, showing flooding due to soil liquefaction in Christchurch

A national memorial service will take place in Christchurch on 18 March. Prince William will attend and tour the affected areas.[149]

Christchurch International Airport

An Air New Zealand Boeing 777 at Wellington airport carrying quake evacuees

Christchurch International Airport is located 12 km (7 mi) northwest of the city centre and was largely unaffected by the earthquake. Flight crews from the U.S. Air National Guard were at the airport, making preparations to return to America, when the quake struck and reported to their Air Wing commander that they were safe and unharmed, and that the airport had water and electricity.[150] Twenty-six members of the New York Air National Guard’s 109th Airlift Wing are currently deployed to the airport, in support of "Operation Deep Freeze" (the U.S. Air Force's military support to U.S. research operations in Antarctica).

The Christchurch-based national air traffic control organisation, Airways New Zealand, closed New Zealand airspace for a short time while they inspected their facilities.[151] Christchurch International Airport was closed to all but military and emergency traffic. [152]

International

"I know that [Australians'] thoughts are with the people of New Zealand as they grapple with this enormous tragedy in Christchurch. ... We will be doing everything we can to work with our New Zealand family, with Prime Minister Key and his emergency services personnel, his military officers, his medical people, his search and rescue teams. We will be working alongside them to give as much relief and assistance to New Zealand as we possibly can."

Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard on the earthquake.[153]

Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard offered John Key any assistance he may request. [154] The Australian Government has also pledged A$5 million (NZ$ 6.7 million[12]) to the Red Cross Appeal.[55] On the 1 March, it was announced that the New South Wales Government would be donating A$1 million (NZ$ 1.3 million[12]) to the victims of the Christchurch Earthquake.[155]

Israel, the United Nations and the European Union offered assistance.[156] Kamalesh Sharma, Commonwealth Secretary-General, sent a message of support to the Prime Minister and stated "our heart and condolences go immediately to the bereaved." He added that the "thoughts and prayers" of the Commonwealth were with the citizens of New Zealand, and Christchurch especially.[157]

Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper released a statement saying: "The thoughts and prayers of Canadians are with all those affected by the earthquake. Canada is standing by to offer any possible assistance to New Zealand in responding to this natural disaster."[158] [159]

David Cameron, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, issued a statement as well as his texting his fellow Commonwealth prime ministers. In his formal statement, he commented that the loss of life was "dreadful" and the "thoughts and prayers of the British people were with them".[160]

Ban Ki-Moon, Secretary-General of the United Nations, issued a statement on behalf of the United Nations expressing his "deep sadness" and stressed the "readiness of the United Nations to contribute to its efforts in any way needed".[157] China gave US$500,000 to the earthquake appeal, and Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao expressed his deep condolences to New Zealand.[161] Twenty Chinese students were reported missing following the quake.[162]

Barack Obama, President of the United States, issued a statement from the White House Press Office on the disaster by way of an official announcement that "On behalf of the American people, Michelle and I extend our deepest condolences to the people of New Zealand and to the families and friends of the victims in Christchurch, which has suffered its second major earthquake in just six months... As our New Zealand friends move forward, may they find some comfort and strength in knowing that they will have the enduring friendship and support of many partners around the world, including the United States." The President also made a call to Prime Minister Key.[163]

Pope Benedict XVI issued an announcement on the earthquake in a statement during his Wednesday audience on 23 February, stating that he was praying for the dead and the injured victims of the devastating earthquake, and encouraging those involved in the rescue efforts, saying that,: "My thoughts turn especially to those that are being severely tested by this tragedy". He expressed concern for the "considerable loss of life and the disappearance of many people, to say nothing of the damage to buildings. Let us ask God to relieve their suffering and to support all who are involved in the rescue operations," he said, asking people to join him in praying for the people who had lost their lives.[157]

Sporting effects

New Zealand Cricket's offices were damaged by the earthquake.[164] Some matches needed to be rescheduled.[165][166] New Zealand team captain Daniel Vettori put his personal memorabilia up for auction.[167]

Economic impact

See also: Earthquake Commission

New Zealand Finance Minister, Bill English, advised that the effects of the 2011 quake were likely to be more costly than the September 2010 quake. His advice was that the 2011 earthquake was a "new event" and that EQC's reinsurance cover was already in place after the previous 2010 event. New Zealand's Earthquake Commission (EQC), a government organisation, levies policyholders to cover a major part of the earthquake risk. The EQC further limits its own risk by taking out cover with a number of large reinsurance companies, for example Munich Re.

The EQC pays out the first NZ$1.5 billion in claims, and the reinsurance companies are liable for all amounts between NZ$1.5 billion and NZ$4 billion. The EQC again covers all amounts above NZ$4 billion. EQC chief executive Ian Simpson said that the $4 billion cap for each earthquake is unlikely to be exceeded by the costs of residential building and land repairs, so $3 billion would be left in the EQC's Natural Disaster Fund after payouts.[168][169][170]

This statement appears to be in direct contrast to the statements in the EQC's official documentation, whih states that as this is "another disaster within a three year period", the 2010 Canterbury Earthquake being the first one, the EQC pays out the first NZ$1 billion in claims, and the reinsurance companies are liable for all amounts between NZ$1 billion and NZ$3.5 billion. The EQC again covers all amounts above NZ$3.5 billion.[171][172] The current EQC contract runs until June 2011.

Claims from the 2010 shock were estimated at NZ$2.75–3.5 billion. Prior to the 2010 quake, the EQC had a fund of NZ$5.93 billion according to the EQC 2010 Annual Report, with NZ$4.43 billion left prior to the 2011 quake, after taking off the NZ$1.5 billion cost.[173]

EQC cover for domestic premises entitles the holder to up to NZ$100,000 plus tax (GST) for each dwelling, with any further amount above that being paid by the policyholder's insurance company. For personal effects, EQC pays out the first NZ$20,000 plus tax. It also covers land damage within 8 metres of a home; this coverage is uncapped.[168]

Insurance Council of New Zealand chief executive Chris Ryan said Tuesday's quake would not have a major effect on residential property, given the epicentre was in the city's commercial heartland. Commercial properties are not insured by the EQC, but by private insurance companies. These insurers underwrite their commercial losses to reinsurers, who will again bear the brunt of these claims. JPMorgan Chase & Co say the total overall losses related to this earthquake may be US$12 billion. That would make it the second most costly earthquake event in history, after the 1994 California earthquake.[13][174]

Earthquake Recovery Minister Gerry Brownlee echoed that fewer claims were expected through the EQC than for 2010. In the 2010 earthquake, 180,000 claims were processed as opposed to the expected 130,000 claims for the 2011 aftershock. The total number of claims for the two events was expected to be 250,000, as Brownlee explained that many of the claims were "overlapping".[175][176]

On 2 March, John Key said he expected an interest rate cut to deal with the earthquake. The reaction to the statement sent the New Zealand dollar down.[177] Cancellation of 2011 census

The Chief Executive of Statistics New Zealand, Geoff Bascand, announced on 25 February that the national census planned for 8 March 2011 will not take place due to the disruption and displacement of people in the Canterbury region, and also the damage sustained by the Statistics Department buildings in Christchurch, which was scheduled to process much of the census. The cancellation will require an amendment to the Statistics Act 1975, which legally requires a census to be taken in 2011, and a revocation by the Governor-General. It is the third time the census has been cancelled in New Zealand; the other occasions occurred in 1931, due to the Great Depression, and in 1941 due to World War II. Most of the NZ$90 million cost of the census would be written off.[178][179]