Chapter Six

Basic Needs, Structural Adjustment and The End of the Cold War

The economy was in disarray. It would be a big success just to get production back to where it was twenty years ago.1

Wonderful people. Terrible government. The African Story.2

[House Foreign Affairs] Chairman Zablocki’s forecast will be put to the test this week when the House takes up the aid appropriation in a climate that many observers regard as the most hostile toward overseas spending in the 30-year history of the aid program.3

The truth is that, whether it likes it or not, USAID is just another of the federal government’s engines for redistributing revenue among the citizenry…. The result is a racial spoils system.4

We aid other countries with whom our relationships may be more nearly correct than cordial, because we believe that it is in our interests to maintain friendly contacts with their governments and their people and to keep them from going behind the Iron Curtain.5

The Search for New Models

Agriculture, Food Aid and Rural Development

Food aid has long been a part of the foreign aid process and historically food has been used as a tool to influence foreign policy.6 The Green Revolution, which dates back to the early 1940s, by focusing on miracle grains through capital intensive measures, defined U.S. foreign aid in agricultural terms in a way that has benefited U.S. farmers and agribusiness.7 With the Green Revolution, the United States had a model for agriculture that was based upon “[y]ears of high power extension work and agricultural education in the literate United States [but which] made good farmers out of only a small fraction of our farm population.”8

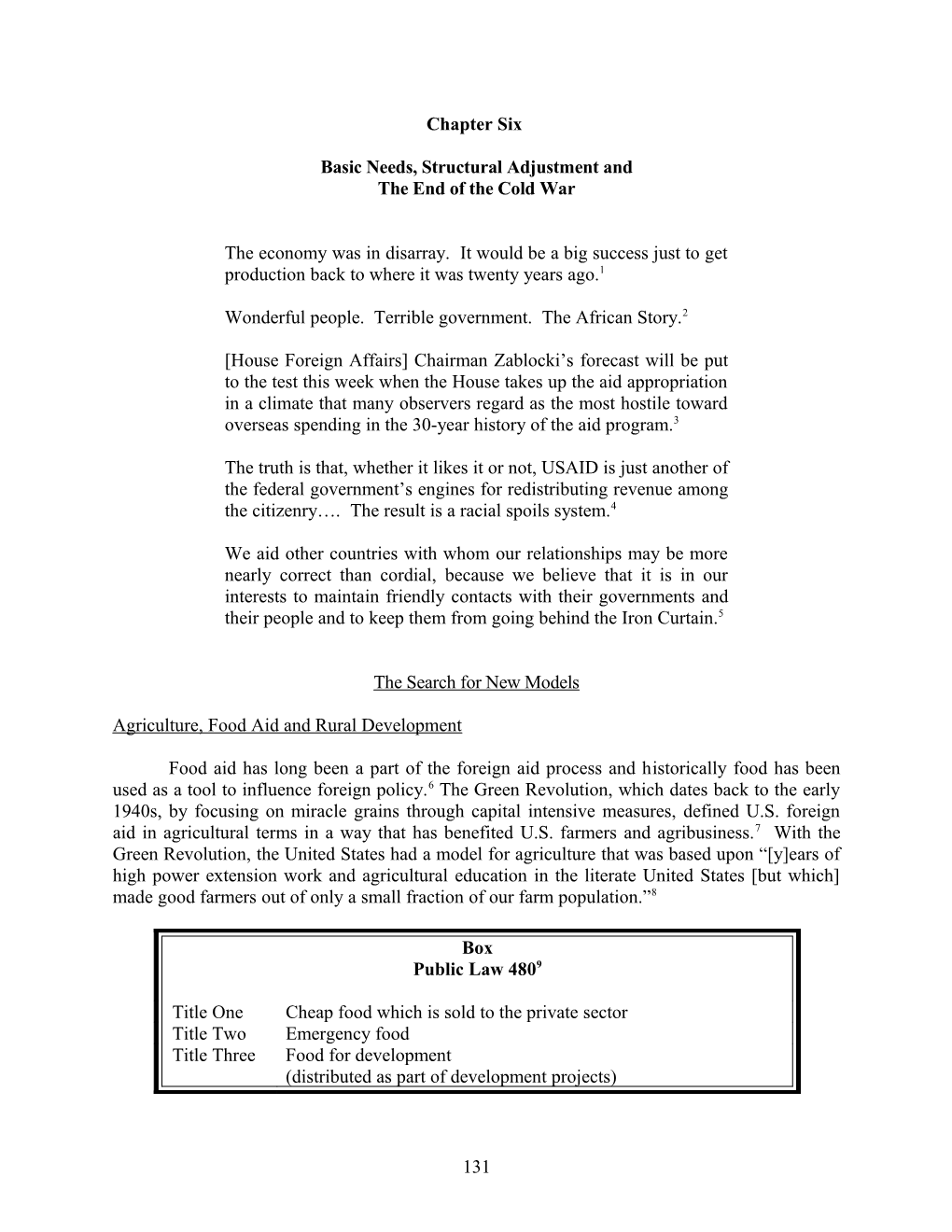

Box Public Law 4809

Title One Cheap food which is sold to the private sector Title Two Emergency food Title Three Food for development (distributed as part of development projects)

131 In 1954, with the passage of Public Law 480, (highlighted above) food became a major component of U.S. foreign aid policy and of domestic subsidies for agriculture. In the first ten years of its foreign aid program, the U.S. distributed American agricultural commodities worth 1.5 billion dollars.10 Table 6.1 shows the pattern of U.S. agricultural commodities distribution between 1954 and 1958. Food assistance, as a companion to agricultural development policy, originated as a mechanism to dispose of U.S. domestic farm surplus, but a secondary intention was also to create future markets for commercial American agricultural exports.11

From the beginning of the post-war period, there were few interest groups in support of foreign aid. Agricultural lobbyists such as the Land Grant Universities and the Farm Bureau Federation were partial exceptions.12 Support for PL 480 was particularly widespread within the American agricultural lobby and agribusiness. A 1957 assessment of foreign aid explained the nature of subsidies from a domestic perspective in this way:

It seems certain that, had large purchases for foreign aid not been made during these years, governmental expenditures under the price-support legislation would have increased markedly, and large stocks would have been acquired.13

Over time, it became increasingly clear that the long term provision of food aid to Less Developed Countries (LDCs) may have been be destructive to the agricultural economy of the recipient country.14 Much concern about foreign aid by the end of the 1950s and beyond focused on the negative impact food aid had on economic growth and agricultural productivity.15 Despite this caution, however, increased capacity in the area of food production in LDCs should be considered an area of at least partial success in terms of foreign aid.

Controversy dogged food policy from the beginning since, “[a]mong those benefits are cash sales for American farmers, reductions in vast U.S. farm surpluses and building future potential abroad for U.S. farm products.”16 The focus of the criticism was on the domestic impact of food aid in the U.S. in terms of food subsidies and protectionism that would keep LDC agricultural production out of the U.S market. According to a recent New York Times article, “The criticism has nothing to do with famine relief, but with American farmers selling their subsidized grain below cost to the rising middle class overseas, much like countries that the United States accuses of dumping their under priced steel here.”17

Beyond food production, however the impact of rural development efforts in LDCs from the mid-1950s to the end of the 1960s was minimal. Nor were development conditions much improved in urban areas. In the post-war period, to its critics, such as John Perkins, the U.S. literally had the power to decide who lived and who died when famine struck in Asia, Africa and Latin America.18

The failure of rural development meant widespread migration to the cities. For those living in an LDC in the 1980s, urban employment was “better than what a rural farmer makes, but basically what a $200 a month job does is it provides a person with maybe an office, telephone (which in many countries does not work anyway), and a place of operations.”19 Part of the rural development mission, of course was to “break up the old, socially and economically self-sufficient village groups.”20 The result, as Linton recognized very early, was a “wreckage

132 [that] is due to fundamental incompatibility between stable, closely integrated folk cultures and an ever-changing machine civilization….”21

Table 6.1

U.S. Exports and Foreign Aid Expenditures, Agricultural Commodities FY 1954-58 (in billion dollars)22

U.S. Agricultural Exports Mutual Security Program (MSP) MSP Expenditures Under MSP Expenditures as Commercial for U.S. Fiscal Year Total Government % of Total Exports Agriculture Programs1 Agriculture Exports Commodities 1954 2.9 2.3 0.6 0.3 10.3 1955 3.1 2.2 0.9 0.5 16.1 1956 3.5 2.1 1.4 0.4 11.4 1957 4.7 2.8 1.9 0.4 8.5 1958 4.0 2.8 1.2 0.2 5.0 1 Including P.L. 480 Programs

The Shift to Basic Needs

The World Bank program for reducing absolute poverty came to include what was called meeting basic needs. By the mid-1970s, the issue of food aid and development had become a central focus of the debate over what was to be called “integrated” rural development, the combination of technical assistance to farmers with the delivery of social services to rural villages. Integrated rural development was a center point to the basic needs approach advocated by the World Bank under Robert McNamara.

Basic needs was the creation of Robert McNamara’s World Bank but was readily accepted as a priority by USAID. Within a few years, stimulated by Robert McNamara’s World Bank and Congressional mandates, the priorities changed again and efforts were redirected towards problems of abject poverty and especially rural development. Robert McNamara brought his basic needs and Keynsian planning focus with him from the Defense Department when he took over as President of the World Bank in late 1967 and he “implemented a system of annual lending quotas that is still in existence.”23 Both basic needs and rural development were keystones of the MacNamara period at the World Bank.

A World Bank-wide program was launched in early 1978 to study the implications for the work of the Bank of accepting the meeting of basic needs within a relatively short period as a basic objective of national development efforts.24 President Jimmy Carter adopted basic needs and it became a keystone of his foreign aid policy. By the late 1970s, basic needs and integrated rural development had become the new order of the day for donors. Basic needs were sometimes defined differently by different people since “the content of the bundle of goods and services that

133 satisfy basic needs varies from one country to another, [although] there is a common core that includes nutrition, education, health, water and sanitation, and shelter.”25

Basic needs came out of a concern for poverty within the U.S. Congress and among development experts and a rising influence in terms of foreign aid policy within Third World nations through their calls for a New International Economic Order, the idea that the Northern Tier states were obligated to help the poor countries of the world because of past wrongs such as slavery, underdevelopment and colonialism.26 Under basic needs, the “Congress directed that future U.S. bilateral assistance focus on critical problems which affect the lives of the poor majorities: food and nutrition, population planning and health, and education and human resources development.”27

In many countries, public investment programs in basic needs, small scale agriculture and integrated rural development had been overwhelmingly the aggregation of what individual donors wanted to finance. The result was poorly designed public investments in rural industrialization and too little attention to smallholder (peasant) agriculture, too much public sector involvement in areas “where the state lacked managerial, technical, and entrepreneurial skills, and too little effort to foster grassroots development.”28

Even at the time, basic needs and integrated rural development had its critics. Speaking of integrated rural development, E. Philip Morgan has pointed out that the term was “cognitively diffuse” and involves a degree of uncertainty with respect to how it intersects with commercial agriculture. The major donor organizations found the linkages between social service delivery and technical assistance for increased productivity confusing. Specifically, donors found it difficult to program through forward and backward linkages which could displace one of the most crucial aspects of rural development, that is institution building, something which normally is not subject to tight programming.29

Critics of rural development and basic needs were skeptical. As Robert Cassen pointed out, very little of aid, even food aid, has been “directed at or had any effect [positive or negative] on the very poorest people, though these people appear to have gained indirectly from aid projects that reduced their food costs.”30 There was little progress on the production of grains throughout the developing world - potatoes in Andean South America, and fish in Southeast Asia. By 1987, “a study found that half of the completed rural-development projects financed by the World Bank in Africa failed.”31 Agriculture projects alone failed one third of the time in West Africa and half the time in East Africa. As Paul Mosley has pointed out:

The main empirical result [in examining foreign aid]…, therefore, is a negative one, namely that there appears to be no statistically significant correlation in any post-war period, either positive or negative, between inflows of development aid and the growth rate of GNP in developing countries….32

The basic needs decade ran from 1970-1980, though some components of the policy lingered on through the end of the twentieth century. By 1980, there had been a fundamental shift in development priorities to basic human needs away from the social service and rural

134 development model though concerns with agricultural development remained. After 1983, except in human or natural crisis areas, basic needs were no longer a top assistance priority.

A U.S. initiated Africa Food Security Initiative (AFSI) in the 1990s showed renewed support for some basic needs principles since “[t]he overall goal of AFSI is to reduce childhood malnutrition by increasing rural people’s incomes.”33 According to a USAID implementation report in the late 1990s:

[Early] progress in implementing the sections of the Act that USAID is required to report on, [included] the Africa Food Security Initiative…, micro-enterprise development…, development of cooperatives and producer groups…, agricultural research and extension…, and non–emergency food programs…. The common elements of all of these successful programs [were to include] a) policies that benefit farmers and rural people; b) support to farmers’ groups and cooperatives; c) support to African commercial ventures serving the needs of farmers and rural people; d) increasing access to credit, markets, and agricultural research, extension, and technology; and e) partnerships with a wide range of NGOs, cooperative development organizations, land grant universities, international agricultural centers, and private firms.34

Criticism of food policies has continued into the new century. Criticism about agricultural subsidies was renewed in 2002, when, as a New York Times report noted:

In Rome, at a United Nations conference on hunger, developing countries pointed this week to the huge new subsidies to American farmers as one of the biggest obstacles to creating vital opportunities for their own farmers and enabling them to climb out of poverty.35

The Poverty Debate

Reducing poverty is difficult. From 1948 through to the present (2007), there have been two views about the nature of poverty that are debated within the donor community. One view sees the origins of poverty as located within an LDC. It is caused by indigenous cultural norms, lack of education, poor political leadership, or poor economic and social policies. Corruption is pointed to as a central problem. For example, “[i]nternational donors say endemic fraud [in LDCs] is making it harder to justify continued aid levels.”36

The other view sees poverty as part of a malfunctioning world system. From this perspective, “[n]early half a century after colonial empires began to crumble and dozens of new countries were born with high hopes of ending dependency and deprivation, a significant number of those nations have seen growth stall and desperate poverty grow instead.”37 By the early 1990s, “the proportion of African children who weighed too little because they ate too little increased. And the amount of food Africans grew per person fell. Africans began to ask: is food aid part of the problem?”38 According to the new left, LDC poverty was

135 not the result of a temporary disequilibrium within the global economy which could be overcome by humanitarian acts such as increased foreign aid. Rather, it [was] the inevitable result of a faulty global economic structure that has frozen economically retarded societies into eternal financial and political dependence upon the rich.39

Following from this, dependency theorists concluded that the vested or class interests in LDC governments are often hostile to the development values and strategies of the social scientist called in to advise them.

The problem according to the new left was that foreign aid programs were not really designed to help poor countries or their people catch up with their rapidly growing needs. At best, foreign aid programs were little more than palliatives, band-aids applied to serious wounds. At worst, “foreign aid is a charitable red herring designed to divert the attention of Third World leadership while permitting powerful economic interests to increase their hammerlock on the global economy.”40

Of course, had poverty been easy to fix, it would have been eliminated years ago.41 Many of the significant disagreements about poverty are ethical and philosophical. One issue involves the responsibility of the international community to poverty alleviation since the search for a solution to poverty may find that it is the internal dynamics of a LDC that has to be addressed.

Other ambiguities revolved around what basic needs were essential to be provided. According to Thomas W. Pogge, a philosophy professor at Columbia University and a long standing critic of the World Bank’s poverty, “If you want to have an absolute income poverty line, you have to start out with some sort of idea about what the important needs or requirements or capabilities of human beings are.”42

Despite the definition and standards defined by the international donor community, there are wide divisions as to how to measure poverty. In part the disputes are methodological. The World Bank often uses a formula based on one U.S. dollar per day as a minimum. According to Daniel Altman, “The dollar-a-day threshold is based on what a single dollar buys at 1990 prices, and it is adjusted for differences in prices among less-developed countries. Just how that is done, though, is a subject of contention.”43 To its critics, the World Bank based its calculations on things that most poor people could never afford to buy. The alternative to the World Bank approach is what has been called the prioritization. The argument here is that any measure should place the greatest weight on the economic plight of the very poorest people.44

Among policy analysts there is currently a search for a middle position. If that middle position is found, according to one observer, “Something more momentous may result, perhaps an alliance between liberals and conservatives to launch a fresh assault on global poverty using less softheaded approaches than in the past.”45 From this perspective, the message is, “Don’t think about just food, but think about what you want people to be able to do in life…and if they can’t do that, you call them poor.”46 The middle position calls for selectivity, “the idea that aid should be showered on countries that are adopting sound policies and taking steps to improve the rule of law, but withheld from others, especially ones that are making little effort to tackle

136 corruption.”47 It is the selectivity argument that would later be adopted in the Millennium Challenge Account.

Policy Reforms and Structural Adjustment

Ronald Reagan and a New Foreign Policy Agenda

When President Reagan came to power in January of 1981, he brought a new set of values to international affairs and grabbed onto a set of policy reform issues that would define his Presidency internationally. The Cold War remained an important component of Ronald Reagan’s foreign aid policy. The Reagan view of intervention was linked to historical views of manifest destiny and visions of an American “Empire” at the end of the Cold War and beyond and U.S. policy towards Central America epitomized the problem. However, the nature of LDC debt was equally troubling to the new Republican administration.

By the early 1980s the internal origins thesis of poverty would become the dominant view of poverty relief within the donor community. During the Reagan administration, “John Williamson, a senior fellow at the Institute for International Economics in Washington, coined the term Washington Consensus to describe a shift in America foreign aid policy that had occurred.”48 The internal origins of poverty thesis had become a part of the Washington Consensus. It was a short step from there to a focus on policy reform and international financial stability.

Box The Search for Orthodoxy

“[William] Bowdler was an accomplished professional diplomat who had been in the Foreign Service for 30 years. Before taking over the Latin American policy job, he had served under Republican and Democratic presidents as ambassador to El Salvador, Guatemala and South Africa and as the State Department’s director of intelligence and research. By traditional Foreign Service standards, those credentials would have entitled Bowdler to a major ambassadorial appointment from the new administration. Instead, within 24 hours of President Reagan’s inaugural, Bowdler was told to empty his desk and leave, that there was no longer a place for him in the Foreign Service. It was the opening move of a purge; in the next few months the Reagan team at the State Department swept aside virtually every career diplomat who had been involved in planning and directing the Carter administration’s Central American policies.”49

During the first four years of the Reagan administration, focus shifted to Central America and anti-communist proxy wars in Africa. Both a rhetoric and a reality can be seen in even a cursory examination of Reagan’s foreign aid policy. In his rhetorical stance Reagan distanced himself from previous administrations creating a kind of prophetic dualism based on

137 unilateralism in his foreign aid and foreign policy assumptions. In reality however Judith Hoover described his policies as one of “technocratic realism.”50 The focus on policy reform demonstrated that realism.

The Reagan administration to his critics, “personified the arrogance of unaccountable power and the calamity of Cold War intrigue in marginal nations across the Third World….”51 According to Judith Hoover, “In terms of fear appeals and motivational appeals, this period is marked by a tendency to combine concern over destruction of authority symbols within Nicaragua such as ‘the church’ with chastisement directed toward those who ‘were showing less of a commitment to freedom than the Soviet Union was showing against it.’”52

Throughout the Cold War, there were elements of unilateralism in U.S. foreign policy and the Reagan years saw a surge in unilateral behavior that would be the basis of post- September 11 responses to international relationships. There were several components to Ronald Reagan’s foreign aid policy. These included a return to support for economic growth, particularly in Asia, a new emphasis on democracy and governance, except where Cold War concerns required support for authoritarian rulers, and a concern for access to energy and other natural resources.

While decrying the waste of foreign aid, it was under Reagan that USAID set up a security assistance social fund for LDCs. Much foreign aid, under President Reagan and his successors, was directed at middle income Asian countries which had good opportunities for success. As Stephen Greenhouse notes, “Not surprisingly, the lion’s share of new investments has gone to some referred to as ‘middle class’ countries - like South Korea, Mexico and Argentina - many of which were avoided by private investors a few years ago because of their debt crises and economic policies.”53

In the 1980s, the U.S. also began to shape its foreign aid programs in order to encourage energy efficiency, renewable energy and natural resource management.54 Its overseas face however did not always complement its energy and environmental policy at home and the idealism of environmental protection did not mesh well with the hard operational assumptions of structural adjustment. Democracy also was said to be a part of the new foreign aid process and in some places it was an important, even a moral imperative. President Reagan labeled democracy a moral imperative. The failure of democracy could lead to conflict, and ultimately the likelihood of millions of refugees.55 In reality, however, during the Reagan administration, democracy and governance took second place to economic reforms and the free market.

More than anything else, however, the Reagan administration would reshape foreign aid towards the problem of international debt. Three sets of inter-related reforms were developed: structural adjustment, conditionality in assistance, and policy reform and privatization. It is to these developments that we now turn.

The Problem of Debt, Structural Adjustment and Privatization

138 Debt was a critical factor in the international development debate as early as the 1960s. As one close observer put it, “When the 1960s are compared as a whole with the 1950s, if one uses aggregate balance of payments statistics, the main accomplishment of this increase in development loans and grants appears to be a tidying up of the Brazilian foreign debt.”56 By 1970, the “debt burden of many developing countries [was] an urgent problem. It was foreseen, but not faced, a decade ago.”57 Ten years later LDC debt was the development problem addressed by donors.

By 1980, debt crushed many LDC economies and debt management dealt a crippling blow to many LDC states particularly in Africa. As Weatherby, et. al point out, “Africa spends four times as much servicing debt as it does on health and education. The region also pays out more in interest on the debt than it receives in trade and other flows.”58 Indebtedness has made foreign aid to many countries close to meaningless. There were almost no prospects of escape from debt.59

The year 1981 is an important one in foreign aid terms. By 1981, the year Robert McNamara stepped down as President of the World Bank, international development policy was being defined by the regime of structural adjustment and public sector reform in many African, Central American and Southeast Asian states. After this year donors focused almost exclusively on the impact of debt on LDCs. The island republic of Jamaica became one of the first countries in the world to come under what came to be called “structural adjustment.” The solution to external debt was ironic, however, since what the donors had come up with was more borrowing.

Under structural adjustment, LDCs would have their loans adjusted and then be allowed by international organizations to borrow more money after the debt relief package had been signed than before they came under structural adjustment. This would allow them to pay back northern tier loans. In most collapsed states, not only was the debt crisis extremely severe but also much of the foreign aid money never got to the source. Foreign aid monies designed to structurally adjust LDC institutions often disappeared to overseas creditors and contractors.

The goal of structural adjustment policies was to open up a country’s domestic economy and move it away from indigenous, import substitution commodities and towards imported goods.60 According to James Baker, then U.S. Treasury Secretary, structural adjustment policies allowed debtor LDCs to grow out of debt, “helped by new finance from the World Bank and commercial banks.”61 Specifically, structural adjustment called “for reforming the ‘Washington Consensus,’ in a way that tethered development money to structural adjustment ‘conditionalities’ including market deregulation, privatization of state-owned enterprises, reduction of the size of government and trade liberalization by the recipient nations.”62 The way that foreign aid loans were used was important. According to Robert Cassen:

Aid receipts were once thought to be associated with reduced domestic savings, but some recent research which distinguished aid for consumption from that used for investments - as most other studies failed to do - found that countries with higher investment-aid receipts did achieve relatively high domestic savings rates.63

139 During the 1980s, rather than training public managers and supporting government programs, as was the case a decade before, donors were training business managers and entrepreneurs, and supporting regional and national business councils as well as organs of civil society. Yet often they were using the same bag of tricks that had been used to support public sector activities since the 1960s. In both the public and the private sectors, management skills continued to be the weak link in the development policy chain. What transformed the picture under structural adjustment was “dividing countries according to the quality of their economic policies.”64 Changes in these economic policies became a second component of the Reagan foreign aid revolution. It is to these policies that we now turn.

Structural adjustment consisted of some seven reforms including 1) fiscal discipline, 2) reordering and reducing public expenditures, 3) tax reform, 4) trade liberalization, 5) liberalization of foreign investment, 6) privatization and 7) deregulation.65 Under structural adjustment reforms, what was needed to complete “the top down reforms [was] a new class structure with an empowered and diverse bourgeoisie made up of business men and women.”66 From this middle class perspective, the “control of the government or the state must therefore be, and is, a fundamental issue in [debates about] the orthodoxy of ‘dependence’ analysis.”67 Structural adjustment, particularly as it is practiced by the U.S. was based on conditionalities.

The United States uses three types of policy-related conditions - conditions precedent, covenants, and prior actions. A “condition precedent” is action that the United States requires a recipient government to take before assistance funds are disbursed. A “covenant” is an action that the United States requires a recipient government to take before, during or after assistance is provided, but is not tied to the disbursement of the funds. A “prior action” is an understanding between the United States and a recipient government (but is not written into any formal agreements) on actions the host government will take prior to the disbursement of U.S. funds.68

After 1981 what came to be called structural adjustment defined foreign aid policy for almost all donors. Structural adjustment meant that neo-orthodox versions of free market capitalism had become the global norm in foreign aid. It was assumed that foreign aid would be given to countries that were both well governed and had adopted market-oriented economic policies may provide a boost to their development. By the mid-1980s, USAID in particular focused on the following issues in setting structural conditions for foreign aid:

1. Changes in interest rates which may discourage savings and result in the misallocation of scarce credit, or create excessive demand which requires administrative rationing;

2. Divestiture of state-owned enterprises to encourage private sector initiative and competition, improve efficiency, and thereby lessen demands on public resources;

3. Exchange-rate policy reforms to encourage exports, eliminate incentives for smuggling and capital flight, and remove other distortions that allocate resources inefficiently;

140 4. The revision of tax structures which inhibit growth;

5. The promotion of export diversification and expansion; and

6. The reduction and/or elimination of government subsidies.69

Advocates of policy reform assumed that they were essential components of foreign aid and that foreign aid would have “a big impact only after countries have made substantial progress in reforming their policies and institutions.”70 The assumption was that direct attempts to improve living standards through aid have had some success but can only be fully implemented in a context of policy reform. There were complications however. In the late 1980s, according to Stanley Hoffman, numerous LDCs continued

to face the problem of the debt…; here what [was] needed, in the short term, [was] extensive relief measures that [would] allow developing countries to concentrate on exports and to afford imports, rather than having to spend their resources on servicing their debt.71

It was up to the multilateral organizations and large bilateral donors to set conditions for debt servicing adjustments. According to Frank Conahan, “The United States frequently conditioned its balance-of-payments assistance in recipient countries by requiring them to obtain and/or comply with [International Monetary] Fund programs.”72

To advocates of structural adjustment in the Reagan administration, central planning, whether in the tropics or in northern tier socialist countries, had impoverished millions of people throughout the twentieth century.73 In policy terms, structural adjustment redefined the way that LDCs were to look at development. The questions were familiar: What, we ask ourselves, should we strive for? “Regrettably,” according to one critic of the Reagan Reforms, “it has long been a convenient notion to identify development merely with economic growth.”74 As one of the architects of privatization has put it:

For developing countries to achieve rapid growth in today’s global economy, they must embrace private, rather than state, ownership of business. They must be receptive to foreign trade, technology, ideas and investment, and they must have governments that accept the rule of law and curb corruption.75

Structural adjustment conditions imposed on debtor states were seen to be “an efficient [but streamlined] public service, a well-run legal system and clearly defined and respected property rights.”76 By the 1990s, structural adjustment conditions also included a demand for stable and democratic political institutions, decentralized governance and the acceptance of the activities of civil society organizations.

Privatization has become widely supported since 1981 as a part of structural adjustment since in “the most successful countries, the value of encouraging private initiative has been amply demonstrated.”77 According to one USAID official in the early 1980s, “It is time to shift to an emphasis on working through the private sector, both profit and non-profit.”78

141 Weakening LDC state structures became a part of policy reform process. According to the privatization lobby, “As we are now seeing in Eastern Europe and have seen in the past in Mexico, Spain, Asia and elsewhere, political weakness leads to fundamental reform.”79 Privatization has been central to that reform process.

At a policy level, the U.S. placed a high priority on the development and implementation by the LDC of effective and efficient economic policies that promoted an open economic system as well as self-sustaining economic growth. The U.S. and its European partners opposed inappropriate subsidies, price and wage controls, as well as prohibitive tariffs, overvalued exchange rates, and interest rate ceilings. Of particular concern was interference with market solutions which would impede economic performance. Unfortunately, the U.S. and its donor partners did not always practice what they preached particularly when it came to subsidies and free trade.

The relationship between political stability and economic development was symbiotic.80 The question asked by some critics was should countries that had bad policies simply be left to their fate? According to advocates of non-governmental organizations, by no means should they be abandoned. Donors should still help by spreading knowledge of a technological or institutional sort through the intercession of NGOs.81 In addition, social support projects should be and are given to NGOs in this situation but no money should to be given to the corrupt state. Beyond this, however, there should be no support directed at state structures prior to the implementation of a policy reform process.

Privatization became an increasing part of the foreign aid process in the 1980s both because of its ideological compatibility with structural adjustment and also because of the impact of domestic U.S. personnel ceilings under Ronald Reagan. The delegation of authority for foreign aid to international and national private sector for-profit and non-profit organizations and their representatives created a number of opportunities for policy reform advisers to play multiple, sometimes conflicting, and ambiguous roles. As a result, they are thus able to facilitate, frustrate, or even damage the processes of development and nation-building. While undertaking activities that serve their personal and/or their professional interests, such advisors may inadvertently undermine key developmental goals of developing nations and organizations that they supposedly serve

Critics, and there were many, suggested that the victims of structural adjustment were the poor and, perhaps, elements of the middle class. As Frank Conahan has put it, “Reductions in government spending usually result in cutbacks in expenditures for power plants, roads, education, and other infrastructure investment. Complementary private-sector investment, which was dependent on this public investment, may also be cut.”82

The carrot offered for policy reforms and donor conditions was the somewhat limited Heavily Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) program which came out of structural adjustment.83 HIPC and social and municipal funds targeted at the delivery of services were meant to address the hardships imposed by policy reform are widely referred to in the World Bank as structural adjustment with a human face. The HIPC program was designed to allow LDCs to use debt

142 payments for economic and social development activities thus reducing their debt obligations. This being noted, it is important to keep in mind that the debt burden of poor countries came about because of lending by the IMF, the World Bank, bilateral donors and most importantly private banks.84 At the same time, self-serving aid or misinformed donor agents often gave LDC policy makers and the public false hopes since the message of structural adjustment was that the reforms advocated were a ticket to economic growth and development.

Economic development and policy reforms depended upon a country’s institutional and political characteristics.85 LDCs may have relatively good macro-economic policies as a result of structural adjustment but ineffective public service delivery and democratic governance mechanisms. If there was a will to correct this problem, then assistance was possible. In such circumstances, assistance should be directed at the creation of an effective public sector. Public sector development was often difficult. When it was not possible, it was suggested that “donors should be more willing to cut back financing to countries with persistently low-quality public sectors.”86

Towards the End of the Century

George Herbert Walker Bush, and William Jefferson Clinton: The End of the Cold War

In looking back it is clear that by 1966 the Soviet Union had declined as a military and an economic power and the United States was de facto the single super power in the world.87 By that time, the U.S. had developed a strategy of what Stillman and Pfaff have called globalism, a form of interventionism based on the assumption that any crisis can be solved.88 The source of crisis at the end of the Cold War would be violence and social disruption. The administrations of George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton, despite their policy differences, provide a bridge of multilateralism in foreign aid and foreign policy which ran from the collapse of the Soviet Union down to September 11, 2001.

Throughout much of the Cold War, the solution to the problem of international competition with the Soviet Union was seen to be a kind of social reform and foreign aid that would align LDC countries to the West.89 However, as Stillman and Pfaff have correctly pointed out, both isolation and globalism (interventionism) shared a “moral fervor that is fundamentally theological in its origins.”90 Emotionally and morally the U.S. has remained largely an isolated nation, despite its alliances, throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty-first.91 Interventionism and particularly unilateralism is fundamentally isolationist in its interaction with the world.92

The year 1980 is a marker in terms of international development. By that year, the Soviet block had lost its position as a significant alternative aid donor, dropping to eight percent of the total global aid budget, from 31 percent in 1961.93 According to Edward Horesh, with the end of the Cold War, it was “now possible to focus and prioritize on the substantive issues of development, without the previous concern of the major powers for consolidation of their political-ideological camps. This concern often clouded the intent, as well as content of development assistance.”94 As the Cold War receded, predominance in foreign aid and technical

143 assistance policy and implementation began to move from government programs to the non- profit and private sector.

Though Soviet power was diminished by 1985, it still defined U.S. foreign aid policy under both Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. The reason for U.S. foreign aid failures during this period, according to John Montgomery, was that policy makers “were unwilling or unable to keep track of the consequences of their decisions that had characterized their performance in…previous encounters with large-scale foreign policy operations.”95 By the end of the Cold War, “aid fatigue was palpable at…annual IMF/World Bank meeting[s]…. Nobody should be surprised that the pressure to cut aid budgets has emerged so soon after the absorption of communist countries into the capitalist order.”96

With the collapse of communism in 1989, a “whole spectrum of American opinion, from Richard Nixon leftwards, [was] is in agreement that Russia must be helped. But wait: help means money. And where, in these deficit-cutting times, is America supposed to find that?”97 The problem for the new Bush administration was where to find the money.

To some critics, George Herbert Walker Bush had all the makings of a foreign policy president. His people were “exceptional, such a contrast to the ‘stand tall’ and ‘how we are neglected’ stuff that Reagan and others spread.”98 As Stanley Hoffman put it in 1989:

Also, the new thinking [in the Bush administration] corresponds to a realistic reading by many Soviet leaders and experts of an international system in which the traditional Soviet mode of behavior - the attempt to impose political control and ideological conformity on others by force - yields limited results, often at exorbitant cost; in which the arms race and the logic of “absolute security” lead only to a higher, more expensive plateau of stalemate and to new forms of insecurity; and in which, in particular, the contest with the United States for influence in the Third World has turned out to be extraordinarily unrewarding.99

There was little aid to Eastern Europe (on a governmental level) or to the Soviet Union prior to 1989. It was in Eastern and Central Europe that the Bush administration had the chance to define new policies at the end of the Cold War. According to Steven Greenhouse:

Mr. Gorbachev implored the industrial nations for extensive aid, but they turned him down, saying his reforms were too half-hearted. Many Sovietologists said the West’s failure to give Mr. Gorbachev billions in aid that he could proudly take back to Moscow was an important factor behind his downfall.100

The failure to support Gorbachev with international assistance may have been a big mistake.

Foreign aid to Eastern Europe began in earnest under the first Bush administration. In 1989, “[t]he Bush Administration asked Congress for $455 million in aid for Poland and Hungary over three years. The House of Representatives voted…to provide $837.5 million to the two countries over three years.”101 As the Eastern European challenge developed, “[c]aught between limited resources and philanthropic instincts, Congress [was] preparing a re-

144 examination of foreign aid programs, but most lawmakers [were] unwilling to deal with a choice as stark as the one…presented.”102

By 1991, a majority in Congress opposed a Marshall Plan style approach to Eastern Europe. Thinking at the time was “with the traditional, anti-communist rationale behind much of U.S. assistance fast losing relevance…the government needs to rethink the goals and criteria for overseas aid or face a taxpayer revolt against the $15 billion annual bill.”103 The neglect was particularly devastating in the post-Soviet Union period to what came to be called the Commonwealth of Independent States.

For Bush, the priority in Eastern and Central Europe was clear. He put it this way in 1992, “To this end, I would like to announce today a plan to support democracy in the states of the former Soviet Union.”104 In 1992, according to Stephen Greenhouse, “The leaders of seven industrial democracies announced a $24 billion, one-year program today to help propel Russia toward democracy, including a contribution from the United States of nearly $4.5 billion.”105

Interest in foreign aid to Eastern and Central Europe was short lived. Ultimately, it was the European Union and a number of individual European countries that defined the future of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union (though for the latter it was much too little too late). The usual combination of aid, policy reform, trade and investment, combined with carrot and stick policies drew Eastern and Central Europe, outside of the Balkans, toward the European Union.

By the end of the 1980s, there was very little consensus within the U.S. that foreign aid was a high priority. However, three specific changes had occurred among American foreign aid policy circles:

1. Critics of aid began to question the basic assumptions of foreign aid and technical assistance, arguing that aid was structurally destructive. Loans in particular, were seen to have a negative impact on LDCs as leaders mortgaged the future of their countries to international institutions.

2. U.S. aid was shrinking rapidly as a percentage of governmental expenditure per capita. In many LDCs the U.S. mission played a minor role compared to European bilaterals and international organizations.

3. Finally, in order to get around personnel ceilings, USAID had dramatically reduced its technical human resources in country and turned to contractors and increasingly grant recipients to deliver services. The U.S. had begun to drop out of international development activities and contract out what was left.106

As the millennium approached, both policy elites and the U.S. public had disengaged from world affairs and become increasingly interested in U.S. domestic affairs, drugs, crime, and the legal and moral shortcomings of American celebrities, “sex, drugs and rock and role” as the old song said.107 As Tim Weiner has noted, “Foreign aid dropped off sharply after the cold war ended.”108 In terms of foreign policy and foreign aid, it was assumed that the “only consistent

145 factor [was] that invariably it is the United States that sets the tone.”109 Later U.S. involvement in Southwest Asia was based on that policy.110

There had been a number of attempts to define a new foreign policy during the first Bush administration. On January 29, 1991, the Director of USAID, Dr. Ronald Roskens, invited three foreign aid specialists to chair three teams that would plan and shape the restructuring of the Agency for International Development.111 Bush’s loss in the 1992 elections cut that process short, however, and little came out of these deliberations. The U.S. and the other industrialized countries transferred fewer donor resources to official development assistance in 1993 than in any previous year since 1973. Further cuts took place in 1994 and 1995.112 It would be left to a new Democratic administration to grapple with foreign aid issues.

The incoming Clinton administration in 1993 faced a “U.S. development assistance program that was in disarray.”113 The Clinton administration defined five broad areas of emphasis for its development assistance: health and population control, environment, democracy and governance, humanitarian relief and economic growth. Support for education in developing countries was downplayed during the Clinton years. Despite the emphasis on reinventing government in domestic policy, there is little evidence that the Clinton approaches had “any impact on the complexities of [foreign aid] programming” or on the U.S. Agency for International Development, in organizational terms.114

At the end of the Cold War, according to Madeleine Albright, there was increasing danger that the United States would take on the role of “world policemen.”115 This appeared to occur in Somalia in 1992 when the U.S. led United Nations humanitarian intervention directly resulted in a war between the United States and one of the clan factions in Mogadishu. 116 The reaction to the failures in Somalia was immediate. Michael Moren pointed out, “The military, the NGOs, and quite a few journalists have now invested heavily in the idea that the world after the Cold War will be one of chaos and violence. In their forecasts it is possible to sense a degree of excitement.”117

The Clinton administration’s approach to foreign policy was hesitant and conservative. Structurally, under Clinton in more than one case, what started as a humanitarian intervention by donors later led to full scale peace keeping interventions (Somalia, Kosovo, and Bosnia are three examples). The Clinton administration was hesitant about peace keeping because it feared being bogged down as in Vietnam, which until Iraq was classic example of a type of intervention feared by American Presidents. The lessons of foreign policy crises of course are hard to learn. Each case is different. As former Secretary of State Albright has noted, “Tragically, the lessons we thought we had just learned in Somalia simply did not apply in Rwanda.”118 Each country, she went on, “has its own history, culture, and language; [and] its own pantheon of heroes and adversaries.…”119

Clinton in foreign aid policy as in domestic policy was a cutback President. In 1993, the “Agency for International Development announced…that 21 missions serving 35 countries and territories would be phased out over the next three years as part of a program of cutbacks.” 120 Clinton operated on continuing resolutions in foreign aid for most of his two terms. The Clinton administration talked a good game however. As Stephen Hook, has put it:

146 Under the Clinton administration, USAID rapidly aligned its objectives with those of the United Nations and other international organizations, pledging to use future aid flows to promote sustainable development and democracy in the development world.121

It is important to keep in mind that there was nothing very unusual about not passing the bill to authorize foreign aid. In 1994, Congress had not approved a foreign aid bill since 1985 though it went on to pass less conspicuous continuing resolutions and appropriations bills to spend the aid money in any event.122

Domestically, foreign aid was under attack throughout the Clinton administration. Well into the first term of the President Clinton:

Secretary of State Warren Christopher warned…of “a new generation of isolationism” emerging in Congress and said the State Department could not sustain more budget cuts without seriously undercutting American foreign policy around the world. In a speech that was part valedictory and part call to action as he prepares to step down next week, Mr. Christopher said a steady decline in foreign-affairs spending had already forced the United States to close consulates and even embassies and to shortchange efforts in some parts of the world in order to address immediate crises in others.123

Although the Clinton administration had made humanitarian intervention a centerpiece of its foreign policy promises, “it [did] a poor job of delivering emergency aid to the people who need[ed] it.”124 According to an article in the New York Times:

Mr. Clinton argues that welfare has to be seen as a “second chance,” rather than a way of life, and promises to stop welfare checks after two years if recipients do not accept training or jobs. In the U.S. at least, foreign aid is perceived in a similar light: it makes sense as an emergency response to disasters but not as a permanent crutch.125

The Clinton administration did continue and expand foreign assistance to Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, as the concept of a transitional country developed. According to Peter Baker:

However, the situation appeared to reflect long-brewing resentment over the presence of a U.S. aid program initially designed to help developing countries [in Africa and Asia]. While many communities across this vast country welcome the Peace Corps volunteers, some officials grumble that Russia is treated as if it were simply another impoverished Third World backwater and that the American volunteers are ill-prepared for their assignments in this former superpower.126

Privatization and democratization were somewhat naively welcomed by Western leaders and publics alike as two key components of success attained by Russia during the 1990s.127

147 According to Eugene Rumer, “Advisers funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) were deployed throughout key Russian government agencies, while nongovernmental organizations funded by USAID offered democracy-building advice to political parties and local governments.”128

By 1997, Eastern Europe came back to haunt U.S. policy makers. On May 20, 1997, USAID, suspended a fourteen million dollar contract with Harvard University. The money was supposed to aid financial-market development in Russia.129 According to the New York Times, “The agency suspended the grants, the last part of a $57 million contract with the Harvard Institute for International Development, after an investigation uncovered what the officials described as evidence that the advisers, Andrei Shleifer and Jonathan Hay, had misused the money.”130

Two developments illustrated the vulnerability of Clinton’s foreign aid policy at the beginning of his second term. First, “[a] day after Mr. Clinton presented a budget that included a modest increase in spending on foreign aid, [the new Secretary of State Madeline Albright] also argued that after four years of a declining foreign-affairs budget, the United States was ‘steadily and unilaterally disarming ourselves.’”131 Secondly, “Mr. Clinton want[ed] to reinstitute a practice, known as tied aid, whereby the U.S. would give development aid to poor countries on condition that they purchase U.S. goods.”132

By 1999, foreign aid, which amounted to much less than one percent of the Federal budget, had been in freefall for fifteen years.133 In that year, Congress authorized some $13.5 billion in expenditures for overseas assistance an amount that remained stable through the millennium down to September 11, 2001. In 2002 the $10 billion American aid budget remained the lowest among rich nations as a percentage of the total economy.134 Nor was there any “agreement to devote major new funding to international debt reduction efforts, beyond covering $1 billion in shortfalls in the current program.”135

During the Presidency of Bill Clinton, the overall foreign-aid budget declined from $14.1 billion in 1993 when he took office to $13.5 billion in 1999. The decline was all the more dramatic after factoring in inflation. The USAID support staff was cut during the same period by about a third, down to 7,000 including both Foreign Service and domestic civil servants.

Conclusion

Overall, as the millennium approached, U.S. interest in foreign aid was waning. Except for a few bankrupt African countries, USAID no longer represented a significant transfer of resources to LDCs relative to the size of their economy.136 By the end of the twentieth century, the path to apathy about international development was clear.

Throughout much of the developing world, as Stephen Hook points out, “a continuous tension existed between the humanitarian functions of U.S. foreign aid in improving social welfare conditions in LDCs and the narrower imperatives of U.S. self-interest.”137 For much of the public however neither was very interesting compared to the O.J. Simpson trial.

148 During the 2000 Presidential campaign, foreign aid had reached its nadir. Candidate Bush not only would attack nation-building and overseas assistance, but there was almost a pride in his supporters’ discovery that Bush did not have a clue as to the names of key foreign leaders who he would be dealing with, such as the President of Pakistan. September 11, 2001 would change all of that. We will turn to those developments in the last two chapters of this book.

149 Endnote

150 1 Robert Klitgaard, Tropical Gangsters: One Man’s Experience with Development and Decadence in Deepest Africa (New York: Basic Books, 1990), p. 48.

2 Paul Theroux, Dark Star Safari: Overland from Cairo to Cape Town (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2003). 3 Graham Hovey, “Foreign Aid Loses Friends in Congress,” New York Times, July 30, 1978. 4 Simon Barber, “US Foreign Aid Has Little to Do With Philanthropy,” Business Day (Johannesburg, July 7, 1992), p.6.

5 Speech by Arthur Z. Gardiner, Director United States Operations Mission in Vietnam, address given to the Saigon Rotary Club on September 22, 1960 (Washington, D.C.: Department of State and U.S. Government Printer, 1961). 6 Walter Cohen, “Herbert Hoover Feeds the World,” in Weissman, ed., The Trojan Horse, p. 151. See also Israel Yost, “The Food for Peace Arsenal,” in Weissman, ed., Trojan Horse, pp. 157-170.

7 Harry Cleaver, “Will the Green Revolution Turn Red?” in The Trojan Horse: A Radical Look at Foreign Aid, Steve Weissman , ed. (Palo Alto, CA.: Rampart Press, 1974), p. 172.

8 William Vogt, “Point Four Propaganda and Reality,” in American Perspective vol. iv. No. 2 (Spring 1950), p. 124. Article pp. 122-129.

9 The United States Economy and the Mutual Security Program. (Washington, D.C.: Department of State, April 1959).

10 James P. Grant, “Towards a More Effective Domestic Political Base for American Economic Assistance Abroad—As Seen by a Practitioner (Paper Prepared for delivery at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, New York, September 8-10, 1960.

11 Caleb Rossiter, The Bureaucratic Struggle for Control of U.S. Foreign Aid: Diplomacy vs. Development in Southern Africa (Boulder, Co.: Westview Press, 1985), p. 19.

12 H. Field Haviland, “Foreign Aid and the Policy Process: 1957,” American Political Science Review, vol. 52, no. 33 (September, 1958), p. 700.

13 Staff Report, The Foreign Aid Programs and the United States Economy, 1948-1957 (Washington, D.C.: National Planning Association, May, 1958), p. 37.

14 Stephen Browne, Beyond Aid: From Patronage to Partnership (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 1999), p. 93.

15 Joseph N. Weatherby, et. al., The Other World: Issues and Politics of the Developing World (New York: Longman, 2000), p. 318. 16 Carl Hartman, “Food for Peace Aids Donor and Recipient,” Los Angeles Times, Oct.28, 1984, p. 7.

17 Elizabeth Becker, “A New Villain in Free Trade: The Farmer on the Dole,” New York Times, (Aug. 25, 2002), p.10. 18 See Israel Yost, “The Food for Peace Arsenal” in Weissman, ed., The Trojan Horse, p. 157-169. See also John Perkins, Confessions of an Economic Hit Man (San Franciso, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2004), which though steeped in conspiracy theory is worth reading. 19 Interview, USAID official, Kinshasa, Zaire, April 1989. Author’s Research Diary. 20 Ralph Linton, “An Anthropologist Views Point Four,” American Perspective, vol. iv, no. 2 (Spring, 1950), p. 119. Article, pp. 113-121.

21 Ibid., p. 119. 22 The United States Economy and the Mutual Security Program. (Washington, D.C.: Department of State, April 1959).

23 Jack Willoughby, “Save the World. Sell the Mercedes,” Financial World, (March 3, 1992), p.44. 24 Mahbub ul Haq and Shahid Javed Burki, “Meeting Basic Needs: An Overview,” World Bank Poverty and Basic Needs Series, (Washington D.C.: World Bank, 1980), p.1. 25 Mahbub ul Haq and Shahid Javed Burki, “Meeting Basic Needs, p.6. 26 Vernon W. Ruttan, United States Development Assistance Policy: The Domestic Politics of Foreign Economic Aid (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, pp. 125-127. 27 Frank C. Conahan, “Foreign Assistance: U.S. Use of Conditions to Achieve Economic Reforms,” GAO Report to U.S. AID, (August 1986), p.8.

28 Pierre Landell-Mills, Ramgopal Agarwala, and Stanley Please, “From Crisis to Sustainable Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Finance and Development, (Johannesburg: December, 1989), p.26. 29 E. Philip Morgan, “Why Aid Fails: An Organizational Interpretation,” Public Lecture, Institute of Development Management, (July 19, 1979), p.18. 30 Robert Cassen, “The Effectiveness of Aid,” Finance & Development (Johannesburg: March 1986), p.12.

31 “Aiding Africa,” Economist, (November 25, 1989), p.47.

32 Paul Mosley, Overseas Aid: Its Defence and Reform (Brighton, UK: Wheatsheaf Books, 1987), p. 139.

33 USAID, “Implementation Report on the Africa: Seeds of Hope Act,” (Washington D.C.: August. 1999), p.6. 34 Ibid., p.5. 35 Elizabeth Becker, “Raising Farm Subsidies, U.S. Widens International Rift,” New York Times, June 25, 2002, p. 1. 36 Chris Hedges, “Up to $1 Billion Reported Stolen by Bosnia Leaders,” New York Times, (August 17, 1999), p.A6. 37 Barbara Crossette, “Givers of Foreign Aid Shifting Their Methods,” New York Times, (February 23, 1992), p.2. 38 “Let Them Eat Cash?” Economist, (April 10, 1993), p.47. 39 Sarah Jackson and Joe Kimmins, “Thunder from the Left: The Radical Critique of Development Assistance,” Communique on Development Issues, no. 4 (Washington, D.C.: Overseas Development Council, January. 1971), p.2. 40 Ibid., p.4.

41 Daniel Altman, “Does a Dollar a Day Keep Poverty Away?” New York Times, (April 26, 2003), p.A19. 42 Ibid. 43 Altman, “Does a Dollar a Day Keep Poverty Away?”, p. A19. 44 Ibid. 45 Paul Blustein, “Treasury Bonds with Bono,” Washington Post, (June 4, 2002), p.C1. 46 Altman “Does a Dollar a Day Keep Poverty Away?, p.A19. 47 Paul Blustein, “The Right Aid Formula This Time Around?” Washington Post, (March 24, 2002), p. A27. 48 Dirk Olin, “Washington Consensus,” Washington Post (May 25, 2003), pp. 21-.22.

49 John M. Goshko, “Clout and Morale Decline; Reaganites’ Raid on the Latin Bureau,” Washington Post, (April 26, 1987), p.A12. 50 Ibid., p.532. 51 Bill Berkeley, The Graves Are Not Yet Full: Race, Tribe and Power in the Heart of Africa (New York: Basic Books, 2001), p. 69.

52 Judith Hoover, “Ronald Reagan’s Failure to Secure Contra-Aid: A Post-Vietnam Shift in Foreign Policy Rhetoric,” Presidential Studies Quarterly, Vol.XXIV No.3, (Summer 1994), p.534. 53 Steven Greenhouse, “Third World Markets Gain Favor,” New York Times, Dec.17, 1993, p.C1. 54 Weatherby, et. al., The Other World, p. 44. 55 Hoover, “Ronald Reagan’s Failure to Secure Contra-Aid”, p.534. 56 Carlos F. Diaz-Alejandro, “Some Aspects of the Brazilian Experience with Foreign Aid,” Center Paper No.177, (New Haven: YaleUniversity Economic Growth Center, 1972). 57 Rudolph A. Peterson, et.al, “U.S. Foreign Assistance in the 1970s: A New Approach,” (Washington, D.C.: Report to the President from the Task Force on International Development, March 4, 1970), p.10. 58 Weatherby, et. al., The Other World, p. 191.

59 Browne, Beyond Aid, p. 71. 60 Mosley, Overseas Aid, p. 108. 61 Stephen Fidler, Financial Times, (March 22, 1989), p.922.

62 Olin, “Washington Consensus,” p.21. 63 Robert Cassen, “The Effectiveness of Aid,” Finance & Development, March 1986, p.11. 64 Ibid. 65 John Williamson “Outline of an Idea, From “Did the Washington Consensus Fail?” (delivered at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington D.C., Nov.6, 2002), quoted by Olin, “Washington Consensus,”, p.21. 66 Shoen “USAID Africa Bureau,” p.9 . 67 Gerald K. Helleiner, “Aid and Dependence in Africa: Issues for Recipients,” in The Politics of Africa: Dependence and Development ( London: Longman, 1979), p. 223. Entire article, pp. 221- 245.

68 Conahan, “Foreign Assistance, p.24. 69 Conahan, “Foreign Assistance,” p.14. 70 Martin Wolf, “Aid, hope and charity,” Financial Times, Nov. 11, 1998. The cite is Quoted from the World Bank report, Assessing Aid, published November 10, 1990. 71 Stanley Hoffmann, “What Should We Do in the World?” Atlantic Monthly, (October 1989), p.95. 72 Conahan, “Foreign Assistance, p.2. 73 William Easterly, The Elusive Quest for Growth (Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press, 2001), p. 33.

74 Wolfgang P. Teschner, “The State of Education Development in the Region,” Panel Review Meeting of Asian Development Bank (March 14-15, 1988), p.1. 75 Jeffrey D. Sachs, “When Foreign Aid Makes a Difference,” New York Times, (February 3, 1997), p.A17. 76 Browne, Beyond Aid, p. 149. 77 Peterson, et.al, “U.S. Foreign Assistance in the 1970s, p.18. 78 Shoen M.D., “USAID Africa Bureau,” p.10. 79 Ibid., p.6. 80 Steven W. Hook, National Interest and Foreign Aid (Boulder CO: Lynne Rienner, 1995). 81 “Making aid work,” Economist, (November 14, 1998), p.88. 82 Frank C. Conahan, “Foreign Assistance,” p.17.

83 Browne, Beyond Aid, p. 149.

84 Easterly, The Elusive Quest for Growth, p. 133. 85 Assessing Aid, p. 53.

86 Ibid., pp. 21-23 and p. 81.

87 Ibid., p. 76.

88 Ibid., pp. 8-9.

89 Edmund Stillman and William Pfaff, Power and Impotence: The Failure of America’s Foreign Policy (New York: Random House, 1966), p. 5 and 11.

90 Ibid., p. 15.

91 This argument was made as early as 1966 by Stillman and Pfaff, in Ibid., p. 52.

92 Ibid., p. 58.

93 Mosley, Overseas Aid, p. 31. 94 Wescott and Osman, “International Resources and Policies, p.1. 95 John D, Montgomery, Aftermath: Tarnished Outcomes of American Foreign Policy (Dover, Mass.: Auburn House Publishing Company, 1986), p. 88. 96 Michael Prowse, “The Twilight of Foreign Aid,” Financial Times, Sept.28, 1992, p.30. 97 “Kind Words, Closed Wallet,” Economist, (March 27, 1993), p.26. 98 Donald Stone, Personal Note to Louis A. Picard, February, 1988. Author’s Research Diary. 99 Stanley Hoffmann, “What Should We Do in the World?” Atlantic Monthly, (October 1989), p.91.

100 Steven Greenhouse, “Bush and Kohl Unveil Plan for 7 Nations to Contribute $24 Billion in Aid for Russia,” New York Times, (April 2, 1992), p.A1.

101 Ferdinand Protzman, “Bonn Giving Poland Aid of $1 Billion,” New York Times, (October 26, 1989), p.1. 102 Susan F. Rasky, “State Dept. Backs Dole on Foreign Aid,” New York Times, (January 17, 1990), p. 1. 103 “Foreign Aid Not Remotely Popular with Voters, Congressmen Say,” Pittsburgh Press, Nov.24, 1991, p.B5. 104 “Excerpts from Bush’s Talk on Aid: Allied Nations ‘Must Win the Peace’,” New York Times, (April 2, 1992), p.A7. 105 Greenhouse, “Bush and Kohl Unveil Plan,” p.A1. 106 Montgomery, Aftermath, p. 84.

107 Chong Guan Kwa and See Seng Tan, “The Keystone of World Order,” in What Does the World Want from America? International Perspectives on U.S. Foreign Policy Alexander T. J. Lennon, ed. (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2002), p. 18. 108 Tim Weiner, “More Entreaties in Monterrey for More Aid to the Poor,” New York Times, (March 22, 2002), p. 1. 109 Jonathan Power, “Breath of Fresh Air in Aid Policy at Last,” The Star, (Johannesburg, September 1, 1997), p.14.

110 Bob Woodward, Plan of Attack (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), p. 132. 111 “AID/W Notice; Subject: Transition Teams,” Office of the Administrator, USAID, January .29, 1991. 112 Ian Smillie, The Alms Bazaar: Altruism Under Fire-Non-Profit Organizations and International Development (London: IT Publications, 1995), p. 19.

113 Ruttan, United States Development Assistance Policies, p. 439.

114 Carol Lancaster, Aid to Africa: So Much to Do: So Little Done (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), p. 108. 115 Madeleine Albright, Madame Secretary: A Memoir (New York: Miramax Books, 2003), p. 153.

116 Mark Bowden, Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War (New York: Penguin, 2000).

117 Maren, The Road to Hell, p. 278. 118 Albright, Madame Secretary, p. 154.

119 Ibid., p. 166. 120 “U.S. Agency for Development Plans to Cut Aid to 35 Nations,” New York Times, (November 20, 1993), p.6.

121 Hook, National Interest and Foreign Aid, p. 125. 122 Leslie H. Gelb, “Foreign Aid Follies,” New York Times, (November 6, 1991), p.A15. 123 Steven Lee Myers, “Christopher Says Budget Cuts Point to ‘a New Isolationism,’” New York Times, (January16, 1997), p.A5. 124 According to an internal report, initiated by Morton H. Halperin, the director of policy planning at the State Department, and based on interviews with senior administration officials, is an unclassified document. See also Jane Perlez, “State Dept. Faults U.S. Aid For War Refugees as Inept,” New York Times, (May 9, 2000), p.A8. 125 Michael Prowse, “The Twilight of Foreign Aid,” Financial Times (Johannesburg, September 28, 1992), p.30. 126 Peter Baker, “Russia Ousting Dozens of Peace Corps Workers.” Washington Post, (Aug. 12, 2002), p. 12. 127 Eugene B. Rumer, “Not Another Soviet Union,” Washington Post (September 24, 2004), p.A25. 128 The USAID gopher allows browsing of development, project, procurement, public affairs and administrative information via gopher.info.usaid.gov. See “Information at Your Fingertips,” Front Lines, (Washington: USAID, April-May 1996), p.10. 129 “Profs in a Pickle,” Economist,(May 24, 1997), p.73. 130 Steven Lee Myers, “A.I.D. Suspends Harvard Grant, Saying Money Was Misused,” New York Times (May 20, 1997), p.A8. 131 Ibid., p.4. 132 “Linking Exports to Aid,” New York Times, (October 19, 1993), p.A14. 133 Dirk Johnson, “Increasing Foreign Aid Would Help Prevent Wars, Clinton Tells V.F.W. Convention,” New York Times, (August, 17, 1999), p.A8. 134 Elisabeth Bumiller, “Bush Proposes Doubling U.S. Support for Education in Africa,” New York Times, June 21, 2002, p. 1. 135 Karen DeYoung, and DeNeen L. Brown, “G-8 Approves an Aid Package for Africa,” Washington Post, (June 28, 2002), p.A19.

136 Lancaster, Aid to Africa, p. 29.

137 Hook, National Interest and Foreign Aid , p. 119.