Babic & Partners

LIDC CONGRESS IN PRAGUE 11-14 OCTOBER 2012

Question A: SMEs and competition rules

Should small and medium enterprises (“SMEs”) be subject to other or specific competition rules?

National Report – Croatia

National Rapporteur: Boris Andrejaš, partner, Babic & Partners

Part I - SMEs IN CONTEXT

1. SMEs’ economic context and legal definition

1.1. Legal definitions of SMEs

Croatian competition law does not include separate legal definition of SME. However, several Croatian laws include provisions that could serve as definition of the SME. First, Croatian Act on Development Incentives for Small Economy1 defines that the undertaking belongs to the “small economy” if the following criteria are met: (i) average annual number of employees is less than 250; (ii) the undertaking is independent (i.e. generally there is no single or joint shareholding exceeding 25% from the entities that are not meeting criteria for “small economy”); and (iii) aggregate annual turnover is less than HRK 216,000,000.00 (approximately EUR 29 million) or the value of the aggregate assets is less than HRK 108,000,000.00 (approximately EUR 14.5 million).

Act on Development Incentives for Small Economy2 also clarifies the difference between (i) micro entities; (ii) small entities and (iii) medium entities falling within the “small economy”. Criteria for the micro entities are as follows: (i) average annual number of employees is less than 10; and (ii) aggregate annual turnover is less than HRK 14,000,000.00 (approximately EUR 1.8 million) or the value of the aggregate assets is less than HRK 7,000,000.00 (approximately EUR 0.9 million). Criteria for the small entities are as follows: (i) average annual number of employees is less than 50; and (ii) aggregate annual turnover is less than HRK 54,000,000.00 (approximately EUR 7.2 million) or the value of the aggregate assets is less than HRK 27,000,000.00 (approximately EUR 3.6 million). The medium entities exceed criteria for small entities but are still within the general ambits of the “small economy”.

In addition, Croatian Accountancy Act3 distinguishes its addressees (i.e. business undertakings) as (i) small, (ii) medium or (iii) large. A “small” undertaking is a company that does not exceed two of the following thresholds: (i) aggregate assets of HRK 32,500,000.00 (approximately EUR 4.3 million) (ii) gross income of HRK 65,000,000.00 (approximately

1 Act on Development Incentives for Small Economy (Official gazette, nos. 29/02 and 63/07), Article 2. 2 Act on Development Incentives for Small Economy (Official gazette, nos. 29/02 and 63/07), Article 3. 3 Accountancy Act (Official gazette, no. 109/07), Article 3. 1 EUR 8.6 million); and (iii) average annual number of employees of 50. A “medium” undertakings is a company that exceed two thresholds for the “small” undertaking but does not exceed two of the following thresholds: (i) aggregate assets of HRK 130,000,000.00 (approximately EUR 17.3 million) (ii) gross income of HRK 260,000,000.00 (approximately EUR 34.6 million); and (iii) average annual number of employees of 250.

Obviously, the definitions from the Act on Development Incentives for Small Economy and from the Accountancy Act are not harmonized and may well serve only for application of the respective statutory rules. However, they may still provide guidance on qualification of SME’s for purposes of competition law.

1.2. The economic perspective

According to data published by the Croatian Ministry of Entrepreneurship and Crafts, SMEs constitute about 99.5% of the veral economic activity and provide for about 63% of the employment in the Republic of Croatia.

1.3. Relevant cases

As indicated above (Section 1.1), there is no definition of the SME’s for purposes of application of Croatian competition law. In addition, since there are no specific rules for SME’s, the Croatian Competition Agency does not indicate in its rulings whether (i) it took into consideration the size of the entities involved and (ii) whether it considers that the parties to the proceedings enjoy some special status (e.g. due to their size). Consequently, the track record of the Croatian Competition Agency cannot be properly analyzed. In addition, it should be noted that Croatian Competition Agency has only recently been granted authority to levy fines for violations of the competition law (Section 8).

On the other hand, there is no available jurisprudence on private antitrust enforcement before Croatian courts.

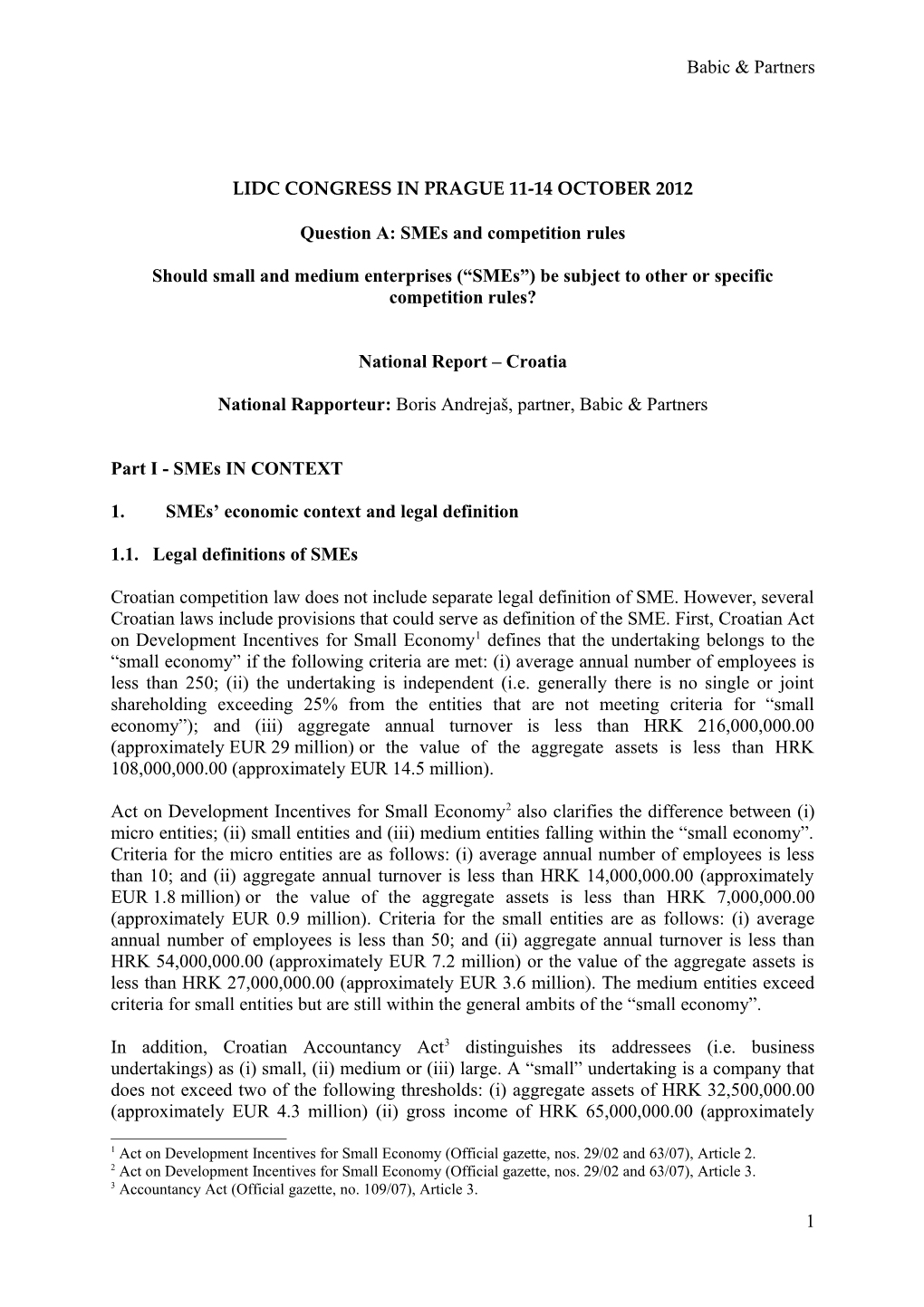

In this context, it should be noted that Table 1.1 below contains the decisions of the Competition Agency in the proceedings against the companies that could possibly qualify as “small economy” within the meaning of Act on Development Incentives for Small Economy.4 Based on the available data, we believe that the legal assessment of the Competition Agency has not been influenced by the economic dimension of the SMEs.

Table 1.1

4 It should be noted that based on the publicly accessible data it is not possible to conclusively establish that certain company qualifies as “small economy” within the meaning of Act on Development Incentives for Small Economy. Consequently, we have prepared Table 1.1 based on our reasonable assessment and it is illustrative only. Subject matter Parties Date Decision no. (class) Procedural order on CCA vs. Consortium of 27 February UP/I 030-02/11- dismissal of the the transport operators 2012 01/050 complaint (prohibited in the area of agreement / abuse of a Međimurje county and dominant position) its municipalities Procedural order on CCA vs. Media d.o.o., 26 January UP/I 030-02/2011- dismissal of the Zagreb and Medical 2012 01/021 initiative (prohibited Intertrade d.o.o., Sveta agreement - cartel) Nedjelja Procedural order on CCA vs. Inel – 15 December UP/I 030-02/2011- dismissal of the medicinske tehnike 2011 01/048 initiative (abuse of a d.o.o., Zagreb and dominant position) Croatian National Institute for Public Health, Zagreb Procedural order on CCA vs. Discovery 15 December UP/I 030-02/2011- dismissal of the d.o.o. 2011 01/022 initiative (abuse of a dominant position) Procedural order on CCA vs. Blitz d.o.o., 01 December UP/I 030-02/2011- dismissal of the Zagreb, Blitz-Cinestar 2011 01/007 initiative (abuse of a d.o.o., Zagreb, Blitz- dominant position) Cinestar Adria d.o.o., Zagreb and Duplicato media d.o.o., Zagreb Ruling on a prohibited Auto Teskera d.o.o., 13 October UP/I 030-02/2010- agreement Velika Mlaka, 2011 01/024 Autokuća Horvat, Zagreb and Morić d.o.o., Velika Mlaka vs. Euro rent sport d.o.o., Zagreb Ruling on a prohibited CCA vs. the Office 21 July 2011 UP/I 030-02/2010- agreement - cartel Products Retailers' 01/018 Association and its members Ruling on termination CCA vs. TM ZAGREB 16 June 2011 UP/I 030-02/2010- of the proceedings d.o.o., Zagreb 01/017 (prohibited agreement) Procedural order on CCA vs. DDL d.o.o., 19 May 2011 UP/I 030-02/2011- dismissal of the Zagreb 01/001 initiative (abuse of a dominant position) Procedural order on CCA vs. I.S. d.o.o. and 07 April UP/I 030-02/2010- dismissal of the MEDIKAL 2011 01/035 initiative (abuse of a INTERTRADE d.o.o. dominant position) Ruling on dismissal of Hosni-compitel d.o.o, 24 March UP/I 030-02/2011- the request (abuse of a Sveti Ivan Žabno vs. 2011 01/009 dominant position) Nikola Andričić, owner of the craft "Andričić", Bjelovar Ruling on rejection of KINO ZADAR FILM 24 February UP/I 030-02/2008- the request (abuse of a d.d., Zadar vs. BLITZ 2011 01/080 dominant position) d.o.o., Zagreb and DUPLICATO MEDIA d.o.o., Zagreb Ruling on a prohibited Rivulus d.o.o., Odra 07 October UP/I 030-02/2008- agreement and M SAN Grupa d.d., 2010 01/061 2. Specific treatment of SMEs under competition law

2.1. The nature and scope of specific treatment for SMEs

Croatian Competition Law does not differentiate between the undertakings based on theri size and SMEs do not enjoy any special treatment. In addition, there are no programs of the Croatian Competition Agency that are specifically addressed to SMEs. However, the Competition Agency is extensively engaged in advocacy efforts targeting e.g. central and regional Chambers of Economy, special subdivisions of the Chamber of Economy (e.g. automotive industry), etc. Bearing in mind various elements (e.g. size of Croatian economy, prevailing size of the business undertakings, etc.) we believe that these advocacy programs are actually mostly used by the SMEs.

2.2. Substantive and procedural rules

SME’s do not enjoy any specific treatment under substantive or procedural rules of Croatian competition law.

2.3. Influence of size and economic power in decisions of the national competition authorities and courts

Available practice of the Competition Agency and competent courts does not reveal that size and economic power influence their decisions. The situations is of course different when substantive law provisions specifically refer to market (economic) power of the undertakings (e.g. provisions on abuse of dominant position, application of the block exemption regulations, etc.).

2.4. Specific programmes addressed to SMEs (compliance, information policies, enhancement of competition enforcement)

To the best of the author’s knowledge, there are no programs of the Croatian Competition Agency that are specifically addressed to SMEs.

3. The role of trade associations

Bearing in mind structure of Croatian economy (Section 1.2), overwhelming majority of members of Croatian trade associations (e.g. members of Croatian Chamber of Economy) are SMEs. Although there are specific policies targeting SMEs (e.g. in the context of development incentives, etc.), there are no specific competition law instruments or programs that are designed for SME’s specifically.

However, trade associations sometimes appear as complainants in the cases before Croatian Competition Agency.5 It is safe to assume that in such cases the complaint originated with SME members of the trade association which in turn serves to provide more credibility in the proceedings before the Competition Agency.

4. Policy recommendations

5 Croatian Chamber of Economy (Sector for Industry) vs. Prirodni Plin Ltd (Natural Gas LLC) of 5 April 2012, class: UP/I 030-02/2011-01/038, no. 580-05/63-2012-131. Bearing in mind structure of Croatian economy (Section 1.2) it might be worthwhile to establish special competition law rules (especially on the substantive level) for SMEs (Section 9). Introduction of such rules should be accompanied with broad advocacy programs implemented by the Croatian Competition Agency and specifically targeting SMEs.

Part II - PUBLIC ANTITRUST ENFORCEMENT AND SMES

5. Substantive and procedural rules applicable to SMEs

5.1. Introduction

Croatian competition law does not differentiate between SME’s and other undertakings. Consequently, there are no specific (different) administrative substantive rules and judicial substantive rules applicable or applied in relation to SMEs.

This also holds true for (i) general rules on administrative procedure (applicable in proceedings before Croatian Competition Agency and (ii) general litigation rules (applicable in proceedings before courts).

5.2. Safe harbours for SMEs

There are no safe harbours designed specifically for SMEs under Croatian competition law. However, certain standard instruments (e.g. de minimis rules6 or block exemption regulations7) take into account the “size” of the entities concerned. These instruments are dominantly market share based rather than turnover based.

5.3. Access to justice

SMEs enjoy all procedural rights under Croatian law and there are no specific obstacles for utilization of these rights by SMEs. In author’s opinion, access of the SME’s to justice, remedies etc. does not need to be specially facilitated. Special position of SMEs should be rather emphasised in the context of the substantive provisions (Section 9) rather than in the context of the access to justice.

This being said, there are instances in both administrative procedure and in judicial procedure that take into account legal nature (rather than size) of the entities involved (e.g. with respect to the delivery of court orders and other decisions, with respect to representation, etc.). In addition, it may be that natural persons would more easily claim benefits of certain protective mechanisms (e.g. both administrative rules and judicial rules oblige the competent court or administrative body to provide additional help/protection to unknowledgeable party).

Bearing in mind current state of development of Croatian competition law and related procedures, there might be no immediate reasons for differentiation between SMEs and other entities on the procedural level. Nevertheless, opening the possibility of collective redress in

6 Regulation on Agreements of Minor Importance (Official gazette, no. 9/11). 7 Regulation on Block Exemption for Agreements in Transport Sector (Official gazette, no. 78/11); Regulation on Block Exemption for Insurance Agreements (Official gazette, no. 78/11); Regulation on Block Exemption for Horizontal Agreements between Undertakings (Official gazette, no. 72/11); Regulation on Block Exemption for Agreements on Distribution and Servicing of Motor Vehicles (Official gazette, no. 37/11); Regulation on Block Exemption for Vertical Agreements between Undertakings (Official gazette, no. 37/11); and Regulation on Block Exemption for Technology Transfer Agreements (Official gazette, no. 9/11). the context of private enforcement (Section 11) might facilitate the procedural position of SMEs to a certain extent.

On the other hand, access to justice in Croatia may be generally impeded due to various factual (e.g. rather ineffective court control over the decisions of the Competition Agency) and legal reasons (e.g. complainants do not enjoy a party status in the proceedings before Competition Agency). However, these impediments do not target SMEs specifically and should not be remedied with “SMEs specific” actions.

6. Fundamental rights of SMEs (as infringers and victims)

Under Croatian law, differences in relation to fundamental rights arise solely from different legal nature of the undertakings (legal entity vs. natural person) and should be so maintained. It would be even worthwhile to expand efforts to alleviate these differences to the extent possible rather than to introduce new grounds for differences (e.g. based on size in relation to SMEs). By way of example, Croatian law8 affords certain personality rights (e.g. right to free market activity) to legal entities and recognizes the right of the legal entities to compensation for violations of their personality rights.9 Introduction of new differences in relation to the fundamental rights would not be feasible approach (especially if the basis for differences is “fluid” category as size) and would possible be questionable from the perspective of certain constitutional guarantees (e.g. equality).

6.1. Complaints

Croatian competition law does not differentiate between SMEs and other undertakings either as infringers or as victims. In this context, all fundamental and other procedural rights are equally afforded (or denied) to the SMEs. In author’s opinion, any deficiency in this respect should not be remedied by actions specifically addressing SMEs’ concerns but rather by broad legislative action that should equally benefit SMEs and all other undertakings (e.g. it might be worthwhile to amend the procedural rules on initiation of the proceedings, party status, down raids, judicial control, etc. which are included in the Croatian Competition Act.10

6.2. Access to the file

Croatian Competition Act11 provides that only parties to the proceedings may access the file of the Competition Agency. It should be noted that the complainant is not a party to the proceedings before the Competition Agency and can access the file only in very limited circumstances. Although we believe that such solution is deficient and should be amended, this deficiency is not impacting specifically SMEs and therefore should not be addressed through measures emphasising difference between the SMEs and other entities.

7. Leniency, settlements and commitment decisions for SMEs

Croatian competition law does not contain provisions that regulate position of SMEs in relation to leniency arrangements, settlements and commitment decisions.

8 Act on Obligations (Official gazette nos. 35/05 and 41/08), Article 19. 9 Act on Obligations (Official gazette nos. 35/05 and 41/08), Article 1100. 10 Competition Act (Official gazette, no. 79/09). 11 Competition Act (Official gazette, no. 79/09), Article 47. However, all these instruments (e.g. leniency) have been introduced in Croatian competition law only recently12 and enforcement practice based on them is virtually non-existent (e.g. no reported leniency decisions, only one report commitment decision). Consequently, it remains to be seen whether their application by the Competition Agency might necessitate special provisions or mechanics for SMEs.

In addition, general rules of the Croatian Competition Act on initiation of the proceedings13 may indeed require improvements (e.g. with respect to anonymous complaints, with respect to procedural rights of the complainants, etc.). However, these problematic issues are not SME specific. Consequently, at this stage it might be advisable to proceed with limited reform of the Croatian Competition Act rather than with introduction of the specific provisions dealing with position of SMEs.

8. Sanctions: different penalties for different size?

Croatian Competition Agency has only recently been granted authority to levy fines for violations of the competition law.14 Under previously applicable Competition Act15, the Competition Agency would only determine that certain entity has violated competition law while the sanctioning phase would be delegated to the competent misdemeanour court. There have been only very few sanctions imposed by the misdemeanour courts (e.g. due to operation of the statute of limitations) and the reported sanctions have been fairly low). In addition, the jurisprudence of misdemeanour courts is not readily accessible and therefore it is difficult to assess to which extent (if at all) have competent courts taken into account differences between SMEs and other economic operators.

However, it might be interesting that the largest reported fine was imposed by the misdemeanour court on the entity that might be considered as SME (the fine amounted to HRK 550,000; approximately EUR 73,000).

As of yet, there are no reported cases on fines imposed by the Competition Agency under the new Competition Act.16

9. Policy recommendations

Croatian competition law does not include any specific provisions addressed to SMEs or protecting SMEs. However, it might be worthwhile to introduce the rules protecting SMEs in specific circumstances. By way of example, the rules of the Croatian Competition Act17 are drafted along the lines of the Article 102 TFEU and there is no available practice on application of this provision on entities with substantial buyer power. Introduction of such specific rules (especially in retail sector) would draw attention of the Competition Agency to these issues and could attract significant benefits (e.g. it is often reported that various suppliers (not only SME suppliers) face significant obstacles with access to larger retail chains). Although such rules should not specifically protect SMEs only, we believe that SME producers and suppliers would ripe the greatest benefits of their introduction.

12 Competition Act (Official gazette, no. 79/09) in force as of 1 October 2010 and Regulation on Immunity from Fines and Reduction of Fines (Official gazette, no. 129/10). 13 Competition Act (Official gazette, no. 79/09), Article 37 et seq. 14 Competition Act (Official gazette, no. 79/09) entered into force on 1 October 2010. 15 Competition Act (Official gazette, no. 122/03). 16 Competition Act (Official gazette, no. 79/09). 17 Competition Act (Official gazette, no. 79/09), Article 13. On the other hand, bearing in mind the structure of Croatian economy and difficulties faced by SME businesses as well as proclaimed governmental support for SME entities, it might be worthwhile to consider introduction of more lenient approach toward allegedly anticompetitive behaviour of the SME entities. By way of example, it is doubtful whether even price fixing arrangement between SMEs (especially when they are faced with significant competitive pressure from larger entity) has any anticompetitive effects especially if one takes into account that merger between these entities (and merger would inevitably result in single pricing) would not be even considered by the Competition Agency (due to the lack of significant turnover). Rather, it appears that such conduct may be even precompetitive and certainly does not warrant investment of efforts and resources of the Competition Agency. In addition fines for such behaviour may have significant anticompetitive effects (e.g. even closure of business and therefore relaxing of competitive pressures). Therefore, in author’s opinion certain SME protective rules should be introduced in Croatian Competition Act.18

Part III - PRIVATE ANTITRUST ENFORCEMENT AND SMES

10. Substantive rules, procedural aspects for SMEs in civil suits

Competition Act19 and Civil Procedure Act20 do not contain any rules designed specifically to protect SMEs in private antitrust enforcing setup. Competition Act21 includes only a short reference that the competent Commercial courts are empowered to hear claims for damages arising out of a breach of the Competition Act. Croatian rules of civil procedure do not contain any specific provisions dealing with the private antitrust enforcement.

Due to these and other reasons, jurisprudence on private antitrust enforcement in Croatia is virtually non-existent.

Furthermore, there are no specific rules in the context of private antitrust enforcement addressing the possibility for a third party to bring an action before civil courts if SME does not take action and we do not believe such a solution would be feasible under general rules governing civil procedures.

Of course, SMEs could generally transfer its claim against the tortfeasor (entity violating competition law) to the third party. Third party would then have autonomous right to institute proceedings against the tortfeasor.

10.1. Obstacles

In author’s opinion, claimant bring before Croatian courts a claim for damages arising from violations of the competition law would have to overcome various procedural and substantive obstacles. Illustration of these obstacles is provided in the following paragraphs. First, it appears that rules of Croatian law on standing of the claimant might pose challenges in the competition law setting. More specifically, while rules on tortuous liability do not specifically exclude different types of claimants (e.g. direct purchasers, competitors and

18 E.g. along the lines of Article 3, German Act Against Restraints of Competition (Gesetz gegen Wettbewerbsbeschränkungen) (available at: http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/gwb/index.html). 19 Competition Act (Official gazette, no. 79/09). 20 Civil Procedure Act (Official gazette, nos. 4/77, 36/77, 6/80, 36/80, 43/82, 69/82, 58/84, 74/87, 57/89, 20/90, 27/90, 35/91, 53/91, 91/92, 112/99, 88/01, 84/08 and 123/08). 21 Competition Act (Official gazette, no. 79/09), Article 69. indirect purchasers)22 it may be difficult for (at least) certain of these categories to show all elements required for successful claim. By way of example, it may be difficult for indirect purchasers to prove causality and quantum of damages due to the fact that they will not have a direct business relationship with the infringer.

In addition, the interests of direct and indirect purchasers may be in conflict where they claim damages for the same infringement. Such claims will normally be mutually exclusive – the direct purchaser is not harmed if the overcharge was passed on to the indirect purchaser and vice versa.

The claims of direct and indirect purchasers may be brought in independent actions which may result in irreconcilable judgments. Purchasers may theoretically decide to cooperate and submit their claims as alternatives in a single action on the basis of Article 196(1) Civil Procedure Act, which provides possibility for independent litigants to participate in the same proceedings. Also, if an action by one purchaser is pending against the infringer, it is conceivable that another purchaser intervenes in support of the infringer in order to prove that the damage was not caused to the plaintiff.23

Second, the general rules on damages have not as yet been tested by the courts in the context of antitrust violations and there are no antitrust specific rules in the relevant legal provisions. It still remains to be seen what difficulties the claimants might face while proving all necessary legal requirements for an award of damages in the context of private antitrust enforcement and how such obstacles will be overcome. By way of example, as the exact quantum of damage suffered may be difficult (if not impossible) to establish, the effectiveness of the remedy will depend on the margin of approximation accepted by the first instance and especially by the higher courts.

Third, it remains to be seen to what extent will the courts accept certain types of defences specific for private antitrust enforcement. General rules of Croatian law appear adequate to support at least some of these defences. By way of example, in an action for damages the defendant may claim that, even if any damage has occurred, it was passed on to the plaintiff’s customers (passing on defence). The essence of this defence is that any award on damages would result in unlawful enrichment of the plaintiff.24 Since passing on is an independent defence made in response to a claim for damages, the burden of proof that passing on has occurred is on the defendant. Also, if the plaintiff has contributed to the damage or the extent of damage, the damages are reduced in proportion to the contribution. If such proportion cannot be established, the court is to award damages taking into account the overall circumstances of each individual case.25 Fourth, it appears that the standard rules on burden of proof may provide another layer of challenges for the claimant. Croatian civil procedure is, for the most part, adversarial in style. According to the Civil Procedure Act, each party has the burden of supplying facts and

22 Generally, any natural person or legal entity has standing to sue or be sued before the Croatian courts. In specific circumstances, standing is given even to groups or associations which do not have a legal personality (Civil Procedure Act (Official gazette nos. 4/77, 36/77, 6/80, 36/80, 43/82, 69/82, 58/84, 74/87, 57/89, 20/90, 27/90, 35/91, 53/91, 91/92, 112/99, 88/01, 84/08, 123/08 and 57/11), Article 77). 23 Civil Procedure Act (Official gazette nos. 4/77, 36/77, 6/80, 36/80, 43/82, 69/82, 58/84, 74/87, 57/89, 20/90, 27/90, 35/91, 53/91, 91/92, 112/99, 88/01, 84/08 and 123/08), Article 206 et seq. 24 M. Bukovac Puvača & V. Butorac (2008), “Izvanugovorna odgovornost za štetu prouzročenu povredom pravila tržišnog natjecanja” [Liability in Tort for Infringements of Competition Law], Hrvatska pravna revija, 12: 32-54. 25 Act on Obligations (Official gazette nos. 35/05 and 41/08), Article 1092. evidence which form the bases of their claims or objections.26 The court may remind the parties of the burden of proof, when it deems appropriate.

Since the primary aim of litigation proceedings is to establish whether or not the claimant's statement of claim is founded, the burden of proof in litigation rests mainly with the claimant. To the extent that the defendant has made objections or allegations to support his defence, it is for the defendant to prove the facts on which he relies.

Fifth, it appears that the claimant may face additional challenges in production of sufficient evidence. The parties have a duty to state all facts supporting their claims and indicate the relevant evidence before the first substantive hearing. Parties may submit new facts and evidence during the substantive hearings or in the pleadings filed between such hearings, but they are liable to the other party for any cost induced thereby, unless new facts and evidence was introduced because of the actions taken by such other party.27 The court may order a party to the proceedings or a third party to produce a specific document requested by the other party.28 If either party refuses to produce the requested document or alleges that it is not in the possession of the document, the court may draw negative inferences from such behaviour.29 In Croatian civil procedure, the court does not have the authority to order wide, American-style discovery.

Sixth, even in case of follow on actions, the reliance on the decisions of the Competition Agency may be rather limited. Courts are generally bound by final and not subject to appeal decisions of the competent authorities. However, this effect is limited to the operative (dispositive) part of the administrative ruling. The rest of the ruling (e.g. statement of reasons) may have only persuasive effect. Therefore, it will depend on particular circumstances if and to what extent previous administrative ruling may be used in the subsequent litigation. In the context of private actions Competition Agency’s decisions would have the status as described above. Obviously, numerous issues of relevance for the private action would be contained only in the statement of reasons of the Agency’s decision (i.e. in its non-binding part that may be revisited by the court) and it remains to be seen to what extent the competent courts would rely on persuasiveness of the non-binding parts of the Agency’s administrative rulings (e.g. the underlying economic and legal analysis).

In addition, different evidentiary rules are applied in different types of proceedings (administrative proceedings before the Competition Agency and private actions proceedings). Therefore, evidence invoked by the parties would have to be produced anew before the litigation court irrespective of whether such evidence has been already produced in the proceedings before the Competition Agency. By way of example, a litigation court generally could not rely on the minutes of the witness testimony occurred during the administrative proceedings before the Competition Agency but would have to examine the witness.

10.2. Best practices

26 Civil Procedure Act (Official gazette nos. 4/77, 36/77, 6/80, 36/80, 43/82, 69/82, 58/84, 74/87, 57/89, 20/90, 27/90, 35/91, 53/91, 91/92, 112/99, 88/01, 84/08, 123/08 and 57/11), Article 7. 27 Civil Procedure Act (Official gazette nos. 4/77, 36/77, 6/80, 36/80, 43/82, 69/82, 58/84, 74/87, 57/89, 20/90, 27/90, 35/91, 53/91, 91/92, 112/99, 88/01, 84/08, 123/08 and 57/11), Article 299. 28 Civil Procedure Act (Official gazette nos. 4/77, 36/77, 6/80, 36/80, 43/82, 69/82, 58/84, 74/87, 57/89, 20/90, 27/90, 35/91, 53/91, 91/92, 112/99, 88/01, 84/08, 123/08 and 57/11), Articles 233 and 234. 29 Civil Procedure Act (Official gazette nos. 4/77, 36/77, 6/80, 36/80, 43/82, 69/82, 58/84, 74/87, 57/89, 20/90, 27/90, 35/91, 53/91, 91/92, 112/99, 88/01, 84/08, 123/08 and 57/11), Article 233(5). Due to the overall lack of jurisprudence and appropriate legislative solutions, there are no best practices addressing private antitrust enforcement in general or in specific SMEs setting.

11. Collective redress

Various types of collective actions as known in different jurisdictions are not available under Croatian procedural rules. This holds true also for competition cases.30

On the other hand, it would be possible that numerous claimants appear in the same private action as co-litigants provided that they satisfy requirements set by the Civil Procedure Act. In this context, they would generally have to prove that their claims arise from substantially the same factual and legal background and that the same court is competent for their claims (e.g. various customers of the dominant undertaking). However, they would be treated as separate parties to the same proceedings (e.g. it may be that some succeed in proving all requirements for the tortfeasor’s liability while others do not).

Right to collective redress could help to improve the rights of the SME’s. Such collective approach might mitigate typical obstacles that are faced by SMEs (e.g. underfunding, access to top legal advice, etc.) and might increase the occurrence of private enforcement actions.

12. The role of trade associations (standing)

Trade associations do not enjoy any special position under Croatian competition law. However, they do appear as complainants in the proceedings before Competition Agency31 and thus arguably facilitate the position of their SME members.

In addition, Croatian litigation rules (that would be applicable in cases of private antitrust enforcement) do not specifically address standing of the trade associations. Provided that the trade associations could show sufficient legal interest (e.g. on the basis of assignment of the victims’ claims or otherwise), they could support their members in private antitrust enforcement proceedings.

13. Policy Recommendations

Specific rules should be introduced to address the possible challenges with private antitrust enforcement. The purpose of these rules would be to facilitate the position of claimants in such actions (e.g. by reversing or relaxing the burden of proof, by using appropriate presumptions (e.g. on quantum of damages), etc.), by providing clear rules on (i) claimants and their standing; (ii) defences allowed to the defendants, etc. However, these rules should address the issues common to all possible claimants and not specifically SMEs.

Part IV. CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

The structure of the Croatian economy (Section 1.2) might warrant special treatment of the SMEs under competition law. However, in author’s opinion this special treatment could be

30 Consumer Protection Act (Official gazette nos. 79/07, 125/07, 79/09 and 89/09) opens a possibility for collective redress for violations of consumer's rights (Article 131). The authority to institute appropriate proceedings is awarded to inter alia, consumer’s association. However, it appears that this mechanism would not cover competition cases and certainly could not result in award of damages. 31Croatian Chamber of Economy (Sector for Industry) vs. Prirodni Plin Ltd (Natural Gas LLC) of 5 April 2012, class: UP/I 030-02/2011-01/038, no. 580-05/63-2012-131 emphasises solely in specific substantive law rules (Section B 5). Introduction of special provisions addressing position of the SMEs in other areas (e.g. procedures before Croatian Competition Agency, private antitrust enforcement, fundamental rights, etc.) might be counterproductive since noted deficiencies should be addressed by broader reform (e.g. in case of rules governing procedures before Croatian Competition Agency) or premature since relevant practice is virtually non-existent (e.g. in leniency programs).