As the Roman Republic expanded, it reached a point where the central government in Rome could not effectively rule the distant provinces. Communications and transportation were especially problematic given the vast extent of the Empire. News of invasion, revolt, natural disaster, or epidemic outbreak was carried by ship or mounted postal service, often requiring much time to reach Rome and for Rome's orders to be realized in the province of origin. For this reason, provincial governors had ultimate control in the name of the Roman Republic. Prior to the establishment of the Empire, the territories of the Roman Republic had been divided among the members of the Second Triumvirate: Mark Antony, Octavian and Lepidus: 1. Antony received the provinces in the East: modern Greece, Albania and the coast of Croatia, and Asia (roughly modern Turkey), Syria, and Cyprus. These lands had previously been conquered by Alexander the Great; thus, much of the aristocracy was of Greek origin. The whole region, especially the major cities, had been largely assimilated into Greek culture, Greek often serving as the lingua franca. 2. Octavian obtained the Roman provinces of the West: Italia (modern Italy), Gaul (modern France), Gallia Belgica (parts of modern Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg), and Hispania (modern Spain and Portugal). These lands also included Greek and Carthaginian colonies in the coastal areas, though Celtic tribes such as Gauls and Celtiberians were culturally dominant. 3. Lepidus received the minor province of Africa (roughly modern Tunisia). Octavian soon took Africa from Lepidus, while adding Sicilia (modern Sicily) to his holdings. Upon the defeat of Mark Antony, a victorious Octavian controlled a united Roman Empire. While the Roman Empire featured many distinct cultures, all were often said to experience gradual Romanization.

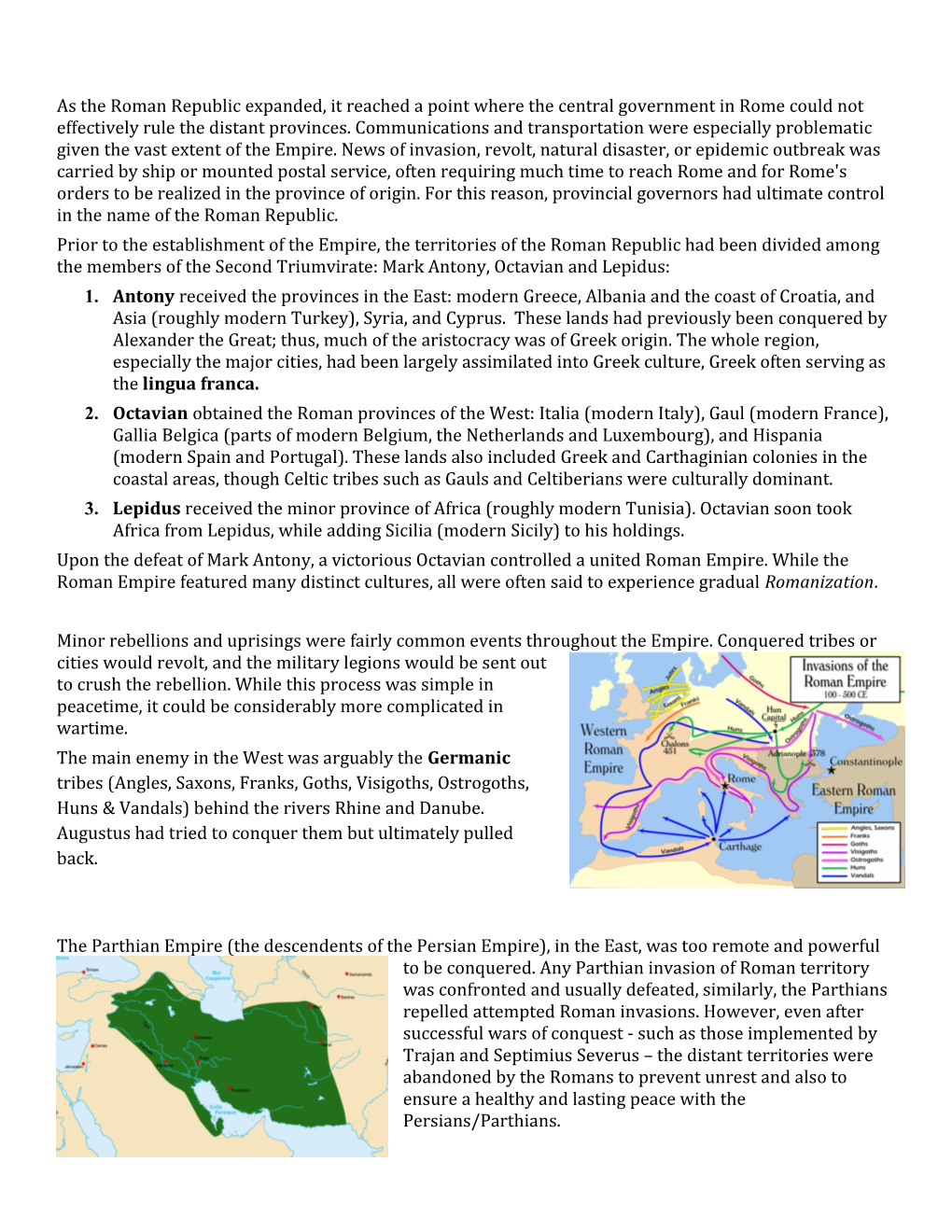

Minor rebellions and uprisings were fairly common events throughout the Empire. Conquered tribes or cities would revolt, and the military legions would be sent out to crush the rebellion. While this process was simple in peacetime, it could be considerably more complicated in wartime. The main enemy in the West was arguably the Germanic tribes (Angles, Saxons, Franks, Goths, Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Huns & Vandals) behind the rivers Rhine and Danube. Augustus had tried to conquer them but ultimately pulled back.

The Parthian Empire (the descendents of the Persian Empire), in the East, was too remote and powerful to be conquered. Any Parthian invasion of Roman territory was confronted and usually defeated, similarly, the Parthians repelled attempted Roman invasions. However, even after successful wars of conquest - such as those implemented by Trajan and Septimius Severus – the distant territories were abandoned by the Romans to prevent unrest and also to ensure a healthy and lasting peace with the Persians/Parthians. Controlling the western border of Rome was reasonably easy because it was relatively close and also because of the disunity between the Germanic tribes, however, controlling both frontiers altogether during wartime was difficult. If the emperor was near the border in the East, chances were high that an ambitious general would rebel in the West and vice- versa. This wartime opportunism plagued many ruling emperors and indeed paved the road to power for several future emperors.

The Crisis of the Third Century (235–284 AD) was a period in which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed under the combined pressures of invasion, civil war, plague, and economic depression. The Crisis began with the assassination of Emperor Alexander Severus at the hands of his own troops, initiating a fifty-year period in which 20–25 individuals claimed the title of Emperor, mostly prominent Roman Army generals, and assumed imperial power over all or part of the Empire.

The external borders were mostly stable during the Crisis of the Third Century, although, between the death of the emperor Aurelian in 275 and the accession of Diocletian ten years later, at least eight emperors or would-be emperors were killed, many assassinated by their own troops. Hence, Rome was in a state of fragility.

Under Diocletian, the political division of the Roman Empire began. In 285, he promoted Maximian to the rank of Augustus (or Emperor) and gave him control of the Western regions of the Empire. In 293, Galerius and Constantius were appointed as Diocletian and Maximian’s subordinates (called Caesars), creating the First Tetrarchy. This system effectively divided the Empire into four major regions and created separate capitals besides Rome as a way to avoid the civil unrest that had marked the 3rd century. In the West, the capitals were: Maximian's Mediolanum (now Milan, Italy) and Constantius' Trier. In the East, the capitals were Sirmium and Nicomedia.

Early Life Flavius Valerius Constantinus, the future emperor Constantine, was born at Naissus (modern day Serbia) on 27 February of 271, 272, or 273. His father was a military officer named Constantius, and his mother a woman of humble background named Helena (later St. Helena). There is good reason to think that Constantius and Helena lived in concubinage rather than in legally recognized marriage. Upon the retirement of Diocletian and Maximian on 1 May 305 Constantius succeeded to the rank of Augustus.

Ascension to Emperor The system of the Tetrarchy quickly ran aground when the Western Roman Empire's Constantius died unexpectedly in 306, and his son Constantine the Great was proclaimed Augustus (Emperor) of the West by the Roman military legions in Britain. A crisis followed as several individuals attempted to rule the Western half.

At the same time the Senate and the Praetorian Guard in Rome had allied themselves with Maxentius, the son of Maximian. In October 306 they proclaimed him emperor. Open hostilities between the two rivals broke out in 312, whereupon Constantine was victorious in battle for control of the Western Roman Empire. The battle became known as the Battle at the Milvian Bridge, a stone bridge across the Tiber River. Constantine is said to have had a vision the preceding night telling him that he would win under a certain sign that included the appearance of a cross set against the sun and certain words in Greek that translate into Latin as: in hoc signo vinces 'you will win under this sign.' This sign and the following victory are credited with convincing Constantine to convert to Christianity, which he did, but not immediately. As the Roman Empire got bigger and new lands and people were taken into it, the conquered people added their Gods or religion to the Roman Pantheon (the name for the multitude of Roman gods). One such new religion was Christianity.

The beginnings of Christianity are very blurry, as far as historical fact is concerned. The birth date of Jesus himself is uncertain. Many point to the year 4 BC as the most likely date for Christ's birth, and yet that remains very uncertain. The year of his death is also not clearly established. It is assumed it took place between AD 26 and AD 36 (most likely though between AD 30 and AD 36), during the reign of Pontius Pilate as prefect of Judaea (similar to a governor).

Historically speaking, Jesus of Nazareth was a charismatic Jewish leader and religious teacher. Evidence of Jesus' life and effect in Palestine is very patchy. He was clearly not one of the militant Jewish radicals (called zealots), although eventually the Roman rulers did perceive him as a security risk. Roman power appointed the priests who were in charge of the religious sites of Palestine. And Jesus openly denounced these priests

This indirect threat to Roman power, together with the Roman perception that Jesus was claiming to be the 'King of the Jews', was the reason for his condemnation. The Roman apparatus saw itself merely dealing with a minor problem which otherwise might have grown into a greater threat to their authority. So in essence, the reason for Jesus' crucifixion was politically motivated. However, his death was hardly noticed by Roman historians.

Jesus' death should have dealt a fatal blow to the memory of his teachings, were it not have been for the determination of his followers. The most effective of these followers in spreading the new religious teachings was Paul of Tarsus, generally known as Saint Paul. St Paul, who held Roman citizenship, is famed for his missionary voyages which took him from Palestine into the empire (Syria, Turkey, Greece and Italy) to spread his new religion to the non- Jews (for until then Christianity was generally understood to be a Jewish sect). The Roman authorities hesitated for a long time over how to deal with this new cult. They largely appreciated this new religion as subversive and potentially dangerous. For Christianity, with its insistence on only one god, seemed to threaten the principle of religious toleration which had guaranteed (religious) peace for so long among the people of the empire. Most of all Christianity clashed with the official state religion of the empire, for Christians refused to perform Caesar worship. This, in the Roman mindset, demonstrated their disloyalty to their rulers. Persecution of the Christians began with Nero's bloody repression in the summer of AD 64. During this time, Rome suffered a terrible fire that burned for six days and seven nights consuming almost three quarters of the city. The people accused the Emperor Nero for the devastation claiming he set the fire for his own amusement. In order to deflect these accusations and calm the people, Nero laid blame for the fire on the Christians. The emperor ordered the arrest of a few members of the sect who, under torture, accused others until the entire Christian populace was implicated and became fair game for retribution. As many of the religious sect that could be found were rounded up and put to death in the most horrific manner for the amusement of the citizens of Rome. The ghastly way the victims were put to death aroused sympathy among many Romans, although most felt their execution justified. The first real recognition Christianity, other than Nero's slaughter, was an inquiry by Emperor Domitian who supposedly, upon hearing that the Christians refused to perform Caesar worship, sent investigators to Galilee to inquire on his family, about fifty years after the crucifixion. They found some poor smallholders, including the great-nephew of Jesus, interrogated them and then released them without charge. The fact however that the Roman emperor should take interest in this sect proves that by this time the Christians no longer merely represented an obscure little sect. Towards the end of the first century the Christians appeared to sever all their ties with the Judaism and established itself independently. With this separation form Judaism, Christianity emerged as a largely unknown religion to the Roman authorities. And Roman ignorance of this new cult bred suspicion. Rumors abounded about secretive Christian rituals: rumors of child sacrifice, incest and cannibalism. Major revolts of the Jews in Judaea in the early second century led to great resentment of the Jews and of the Christians, who were still largely understood by the Romans to be a Jewish sect. The repressions which followed for both Christians and Jews were severe. During the second century AD Christians were persecuted for their beliefs largely because these did not allow them to give the reverence to the images of the gods and of the emperor. Also their act of worship violated the law of Trajan, forbidding meetings of secret societies. To the government, it was civil disobedience. The Christians themselves meanwhile thought such edicts suppressed their freedom of worship. However, despite such differences, with Emperor Trajan a period of toleration appeared to set in.

But with the reign of Diocletian things would change. Towards the end of his long reign, Diocletian became ever more concerned about the high positions held by many Christians in Roman society and, particularly, the army. On a visit to the Oracle of Apollo, he was advised by the pagan oracle to halt the rise of the Christians. And so on 23 February AD 303, on the Roman day of the gods of boundaries, the terminalia, Diocletian enacted what was to become perhaps the greatest persecution of Christians under Roman rule.

Diocletian and, perhaps all the more viciously, his Caesar Galerius launched a serious purge against the sect which they saw as becoming far too powerful and hence, too dangerous. In Rome, Syria, Egypt and Asia Minor (Turkey) the Christians suffered most. However, in the west, beyond the immediate grasp of the two persecutors things were far less ferocious.

The key moment in the establishment if Christianity as the predominant religion of the Roman empire, happened in AD 312 when emperor Constantine on the eve before battle against the rival emperor Maxentius had a vision of the sign of Christ (the so called chi- rho symbol) in a dream. And Constantine was to have the symbol inscribed on his helmet and ordered all his soldiers (or at least those of his bodyguard) to point it on their shields.

It was after the crushing victory he inflicted on his opponent against overwhelming odds that Constantine declared he owed his victory to the god of the Christians. However, Constantine's claim to conversion is not without controversy. There are many who see in his conversion rather the political realization of the potential power of Christianity instead of any celestial vision. Constantine had inherited a very tolerant attitude towards Christians from his father, but for the years of his rule previous to that fateful night in AD 312 there was no definite indication of any gradual conversion towards the Christian faith. Until AD 324 Constantine appeared to on purposely blur the distinction of which god it was he followed, the Christian god or pagan sun god Sol. Perhaps at this time he truly hadn't made up his mind yet. Perhaps it was just that he felt his power was not yet established enough to confront the pagan majority of the empire with a Christian ruler. However, substantial gestures were made toward the Christians very soon after the fateful Battle of the Milvian Bridge in AD 312. Already in AD 313 tax exemptions were granted to Christian clergy and money was granted to rebuild the major churches in Rome.

But once Constantine had defeated his last rival emperor Licinius in AD 324, the last of Constantine's restraint disappeared and a Christian emperor (or at least one who championed the Christian cause) ruled over the entire empire. He built a vast new basilica church on the Vatican hill, where reputedly St Peter had been martyred. Other great churches were built by Constantine, such as the great St John Lateran in Rome or the reconstruction of the great church of Nicomedia which had been destroyed by Diocletian.

Apart from building great monuments to Christianity, Constantine now also became openly hostile toward the pagans. Even pagan sacrifice itself was forbidden. Pagan temples (except those of the previous official Roman state cult) had their treasures confiscated. These treasures were largely given to the Christian churches instead. Some cults which were deemed sexually immoral by Christian standards were forbidden and their temples were razed. Gruesomely brutal laws were introduced to enforce Christian sexual morality. Constantine was evidently not an emperor who had decided to gradually educate the people of his empire to this new religion. Far more the empire was shocked into a new religious order.

The Roman Empire lasted from 27 BC - 476 AD, a period exceeding 500 years. At its most powerful the territories of the Roman Empire included lands in West and South Europe (the lands around the Mediterranean), Britain, Asia Minor, North Africa including Egypt. The Decline of the Roman Empire was due to many reasons but the major causes of the decline are detailed below. There was no specific order of the causes for the fall of the Roman Empire. Different causes occurred over its time period of over five hundred years.

When Did Rome Fall? Some say the split into an eastern and western empire governed by separate emperors caused Rome to fall. The eastern half became the Byzantine Empire, with its capital at Constantinople (modern Istanbul). The western half remained centered in Italy. Many say the Fall of Rome was an ongoing process, lasting more than a century. Since Rome still exists, it is argued that it never fell. Some prefer to say that Rome adapted rather than fell.

Why did Rome Fall? There are adherents to single factors, but more people think a combination of such factors as Christianity, decadence, lead, monetary trouble, and military problems caused the Fall of Rome. Imperial incompetence and chance could be added to the list. Even the rise of Islam is proposed as the reason for Rome's fall, by some who think the Fall of Rome happened at Constantinople in A.D. 1453. 1. Christianity Many even blame the initiation of Christianity for the decline of the Empire. Christianity made many Roman citizens into pacifists, making it more difficult to defend against the barbarian attackers. Also money used to build churches could have been used to maintain the Roman Empire.

2. Decline in Morals and Values Even during Pax Romana (A long period from Augustus to Marcus Aurelius when the Roman Empire was stable and relatively peaceful) there were 32,000 prostitutes in Rome. Emperors like Caligula and Nero became infamous for wasting money on lavish parties where guests drank and ate until they became sick. The most popular amusement was watching the gladiatorial combats in the Colosseum.

3. Public Health There were many public health and environmental problems. Many of the wealthy had water brought to their homes through lead pipes. Previously the aqueducts had even purified the water but at the end lead pipes were thought to be preferable. The wealthy death rate was very high. The continuous interaction of people at the Colosseum, the blood and death probable spread disease. Those who lived on the streets in continuous contact allowed for an uninterrupted strain of disease much like the homeless in the poorer run shelters of today. Alcohol use increased as well adding to the incompetency of the general public.

4. Political Corruption One of the most difficult problems was choosing a new emperor. Unlike Greece where transition may not have been smooth but was at least consistent, the Romans never created an effective system to determine how new emperors would be selected. The choice was always open to debate between the old emperor, the Senate, the Praetorian Guard (the emperor’s private army), and the army. Gradually, the Praetorian Guard gained complete authority to choose the new emperor, who rewarded the guard who then became more influential, perpetuating the cycle. Then in 186 A. D. the army strangled the new emperor, the practice began of selling the throne to the highest bidder. During the next 100 years, Rome had 37 different emperors - 25 of whom were removed from office by assassination. This contributed to the overall weaknesses, decline and fall of the empire.

5. Unemployment During the latter years of the empire farming was done on large estates called latifundia that were owned by wealthy men who used slave labor. A farmer who had to pay workmen could not produce goods as cheaply. Many farmers could not compete with these low prices and lost or sold their farms. This not only undermined the citizen farmer who passed his values to his family, but also filled the cities with unemployed people. At one time, the emperor was importing grain to feed more than 100,000 people in Rome alone. These people were not only a burden but also had little to do but cause trouble and contribute to an ever increasing crime rate. 6. Inflation The roman economy suffered from inflation (an increase in prices) beginning after the reign of Marcus Aurelius. Once the Romans stopped conquering new lands, the flow of gold into the Roman economy decreased. Yet much gold was being spent by the Romans to pay for luxury items. This meant that there was less gold to use in coins. As the amount of gold used in coins decreased, the coins became less valuable. To make up for this loss in value, merchants raised the prices on the goods they sold. Many people stopped using coins and began to barter to get what they needed. Eventually, salaries had to be paid in food and clothing, and taxes were collected in fruits and vegetables.

7. Urban decay Wealthy Romans lived in a domus, or house, with marble walls, floors with intricate colored tiles, and windows made of small panes of glass. Most Romans, however, were not rich, they lived in small smelly rooms in apartment houses with six or more stories called insulas. Each insula covered an entire block. At one time there were 44,000 apartment houses within the city walls of Rome. First-floor apartments were not occupied by the poor since these living quarters rented for about $100 a year. The more shaky wooden stairs a family had to climb, the cheaper the rent became. The upper apartments that the poor rented for $40 a year were hot, dirty, crowed, and dangerous. Anyone who could not pay the rent was forced to move out and live on the crime- infested streets. Because of this cities began to decay.

8. Inferior Technology Another factor that had contributed to decline and fall of the Roman Empire was that during the last 400 years of the empire, the scientific achievements of the Romans were limited almost entirely to engineering and the organization of public services. They built marvelous roads, bridges, and aqueducts. They established the first system of medicine for the benefit of the poor. But since the Romans relied so much on human and animal labor, they failed to invent many new machines or find new technology to produce goods more efficiently. They could not provide enough goods for their growing population. They were no longer conquering other civilizations and adapting their technology, they were actually losing territory they could not longer maintain with their legions.

9. Military Spending Maintaining an army to defend the border of the Empire from barbarian attacks was a constant drain on the government. Military spending left few resources for other vital activities, such as providing public housing and maintaining quality roads and aqueducts. Frustrated Romans lost their desire to defend the Empire. The empire had to begin hiring soldiers recruited from the unemployed city mobs or worse from foreign counties. Such an army was not only unreliable, but very expensive. The emperors were forced to raise taxes frequently which in turn led again to increased inflation.

10. The Final Blows For years, the well-disciplined Roman army held the barbarians of Germany back. Then in the third century A. D. the Roman soldiers were pulled back from the Rhine-Danube frontier to fight civil war in Italy. This left the Roman border open to attack. Gradually Germanic hunters and herders from the north began to overtake Roman lands in Greece and Gaul (later France). Then in 476 A. D. the Germanic general Odovacar overthrew the last of the Roman Emperors, Augustulus Romulus. From then on the western part of the Empire was ruled by Germanic chieftain. Roads and bridges were left in disrepair and fields left untilled. Pirates and bandits made travel unsafe. Cities could not be maintained without goods from the farms, trade and business began to disappear. And Rome was no more in the West. The Byzantine Empire (or Byzantium) was the Eastern Roman Empire and was centered on the capital of Constantinople. This remaining portion of the Roman Empire lasted until 1453 with the death of Constantine XI and the capture of Constantinople by Mehmed II, leader of the Ottoman Turks.