Users/Apple/Documents/WORK /Unit44/2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Million M2: When Will the State Recover Them?

issue number 158 |September 2015 SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT IN LEBANON HEFTY COST AND UNSOLVED CRISIS POSTPONING THE RELEASE OF LEBANON’S ARMY COMMANDER THE MONTHLY INTERVIEWS NABIL ZANTOUT www.monthlymagazine.com Published by Information International sal GENERAL MANAGER AT IBC USURPATION OF COASTAL PUBLIC PROPERTY 5 MILLION M2: WHEN WILL THE STATE RECOVER THEM? Lebanon 5,000LL | Saudi Arabia 15SR | UAE 15DHR | Jordan 2JD| Syria 75SYP | Iraq 3,500IQD | Kuwait 1.5KD | Qatar 15QR | Bahrain 2BD | Oman 2OR | Yemen 15YRI | Egypt 10EP | Europe 5Euros September INDEX 2015 4 USURPATION OF COASTAL PUBLIC PROPERTY 5 MILLION M2: WHEN WILL THE STATE RECOVER THEM? 16 2013 CENTRAL INSPECTION REPORT 19 SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT IN LEBANON HEFTY COST AND UNSOLVED CRISIS 22 POSTPONING THE RELEASE OF LEBANON’S ARMY COMMANDER 24 JAL EL-DIB: BETWEEN THE TUNNEL AND THE BRIDGE 25 PARLIAMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN: QONUNCHILIK PALATASI P: 28 P: 16 26 RASHID BAYDOUN (1889-1971) 28 INTERVIEW: NABIL ZANTOUT GENERAL MANAGER AT IBC 31 INJAZ LEBANON 33 POPULAR CULTURE 34 DEBUNKING MYTH#97: SHOULD WE BRUSH OUR TEETH IMMEDIATELY AFTER EATING? 35 MUST-READ BOOKS: DAR SADER- IN BEIRUT... A THOUGHT SPARKED UP 36 MUST-READ CHILDREN’S BOOK: THE BANANA P: 19 37 LEBANON FAMILIES: QARQOUTI FAMILIES 38 DISCOVER LEBANON: SMAR JBEIL 39 DISCOVER THE WORLD: NAURU 40 JULY 2015 HIGHLIGHTS 49 REAL ESTATE PRICES - JULY 2015 44 THIS MONTH IN HISTORY- LEBANON 50 DID YOU KNOW THAT?: 2014 FIFA WORLD CIVIL WAR DIARIES CUP THE ZGHARTA-TRIPOLI FRONT 40 YEARS AGO 50 RAFIC HARIRI INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT 47 THIS MONTH IN HISTORY- ARAB WORLD - JORDAN TRAFFIC - JULY 2015 BLACK SEPTEMBER EVENTS 51 LEBANON’S STATS 48 TERRORIST GROUPS PRETENDING TO STAND FOR ISLAM (8) ANSAR AL-SHARIA’A: ORIGINATING FROM LIBYA AND ESPOUSING ISLAMIC SHARIA’A |EDITORIAL Iskandar Riachi Below are excerpts from chapter 40 of Iskandar Riachi’s book Before and After, which was published in Lebanon in the 1950s. -

Banks in Lebanon

932-933.qxd 14/01/2011 09:13 Õ Page 2 AL BAYAN BUSINESS GUIDE USEFUL NUMBERS Airport International Calls (100) Ports - Information (1) 628000-629065/6 Beirut (1) 580211/2/3/4/5/6 - 581400 - ADMINISTRATION (1) 629125/130 Internal Security Forces (112) Byblos (9) 540054 - Customs (1) 629160 Chika (6) 820101 National Defense (1701) (1702) Jounieh (9) 640038 Civil Defence (125) Saida (7) 752221 Tripoli (6) 600789 Complaints & Review (119) Ogero (1515) Tyr (7) 741596 Consumer Services Protection (1739) Police (160) Water Beirut (1) 386761/2 Red Cross (140) Dbaye (4) 542988- 543471 Electricity (145) (1707) Barouk (5) 554283 Telephone Repairs (113) Jounieh (9) 915055/6 Fire Department (175) Metn (1) 899416 Saida (7) 721271 General Security (1717) VAT (1710) Tripoli (6) 601276 Tyr (7) 740194 Information (120) Weather (1718) Zahle (8) 800235/722 ASSOCIATIONS, SYNDICATES & OTHER ORGANIZATIONS - MARBLE AND CEMENT (1)331220 KESRWAN (9)926135 BEIRUT - PAPER & PACKAGING (1)443106 NORTH METN (4)926072-920414 - PHARMACIES (1)425651-426041 - ACCOUNTANTS (1)616013/131- (3)366161 SOUTH METN (5)436766 - PLASTIC PRODUCERS (1)434126 - ACTORS (1)383407 - LAWYERS - PORT EMPLOYEES (1) 581284 - ADVERTISING (1)894545 - PRESS (1)865519-800351 ALEY (5)554278 - AUDITOR (1)322075 BAABDA (5)920616-924183 - ARTIST (1)383401 - R.D.C.L. (BUSINESSMEN) (1)320450 DAIR AL KAMAR (5)510244 - BANKS (1)970500 - READY WEAR (3)879707-(3)236999 - CARS DRIVERS (1)300448 - RESTAURANTS & CAFE (1)363040 JBEIL (9)541640 - CHEMICAL (1)499851/46 - TELEVISIONS (5)429740 JDEIDET EL METN (1)892548 - CONTRACTORS (5)454769 - TEXTILLES (5)450077-456151 JOUNIEH (9)915051-930750 - TOURISM JOURNALISTS (1)349251 - DENTISTS (1)611222/555 - SOCKS (9)906135 - TRADERS (1)347997-345735 - DOCTORS (1)610710 - TANNERS (9)911600 - ENGINEERS (1)850111 - TRADERS & IND. -

Community Development Unit

Council for Development and Reconstruction Economic and Social Fund for Development (ESFD) Project Community Development Unit Formulation of a Strategy for Social Development in Lebanon Beirut December 2005 LBN/B7-4100/IB/99/0225/S06/0803 Formulation of a Strategy for Social Development in Lebanon Council for Development and Reconstruction Economic and Social Fund for Development (ESFD) Project Table of Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms 1. Executive Summary ………………………………………………………. 1 1.1. Definition of Social Development ……………………… .… 1 1.2. Goal and targets for Social Development ………………………. 1 1.3. Status of Social Development Indicators and Strategy Outline….. 2 1.4. Poverty Mapping, Rural Periphery and Vulnerable Groups………. 3 1.5. Strategy Outline ……………………………………………………… 4 2. Definition of Social Development in Lebanon ………………………… 6 2.1. International Definitions ……………………………………………... 6 2.1.1. The World Bank Concept of Social Development …………. 6 2.1.2. The World Summit Concept of Social Development ………. 6 2.1.3. UNDP Focus on Social Development and Poverty Eradication……………………………………………………………... 7 2.1.4. The European Commission (EC) Concept of Social Development……………………………………………………… 7 2.1.5. New Development Concepts, Goals and Targets ……….. 8 2.2 Historic Context in Lebanon …………………………………………. 9 2.2.1 After Independence: The unfinished transition from a rural economy to a modern competitive economy ……………… 9 2.2.2. Social Consequences after the War ………………………. 10 2.2.3. Postwar Economic and Social Policies …………………… 11 2.3 Definition of Social Development in the Lebanese Context ……... 13 2.3.1. Extensive Traditional Definition ……………………………. 13 2.3.2. Focused and Dynamic Definition of Social Development in the Lebanese Context …………………………………….. 13 2.3.3. Balanced Development ………………………………………. -

Promoting Peace and Reconciliation in Lebanon Through Art

22 September 24, 2017 Culture Promoting peace and reconciliation in Lebanon through art Samar Kadi in southern Lebanon, which was occupied by Israel for more than 20 years. Beirut “I go to these places, put the canvases on the floor to let them hat if her art could absorb the energy of the space. I help bring recon- hold healing ceremonies, which is ciliation and peace a process of meditation, chanting to her violence- and sacred sound followed with a plagued country? fire ceremony from objects of the WIs it possible for Beirut, which has land as a symbolism of purification long been linked to war and vio- and releasing. With the ashes, I cre- lence, to become the peace capi- ate ink on site and that’s what I use tal of the world? With these ques- to paint with,” el-Khalil said. tions in mind, Lebanese artist Zena With a piece of cloth, usually a el-Khalil set out on a five-year pro- veil or a koufieh (Palestinian scarf), Absorbing energy. “Grand Hotel Sofar.” Ash, ink and pigment on canvas. (Courtesy of Zena el- Khalil) ject that culminated in a 40-day the artist strikes the canvases hard, exhibition titled “Sacred Catastro- creating imprints. phe: Healing Lebanon.” “No two paintings are ever the they pass… It is literally a forest sense of well-being and healing. If you don’t know what love is, you The display, including paintings, same, because the energy of each of remembrance. The issue of the Workshops, events, lectures and cannot give it to others… Only by sculptures and an installation, space is so different and it directs missing is a delicate political issue. -

Updated Master Plan for the Closure and Rehabilitation

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. UPDATED MASTER PLAN FOR THE CLOSURE AND REHABILITATION OF UNCONTROLLED DUMPSITES THROUGHOUT THE COUNTRY OF LEBANON Volume A JUNE 2017 Copyright © 2017 All rights reserved for United Nations Development Programme and the Ministry of Environment UNDP is the UN's global development network, advocating for change and connecting countries to knowledge, experience and resources to help people build a better life. We are on the ground in nearly 170 countries, working with them on their own solutions to global and national development challenges. As they develop local capacity, they draw on the people of UNDP and our wide range of partners. Disclaimer The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of its authors, and do not necessarily reect the opinion of the Ministry of Environment or the United Nations Development Programme, who will not accept any liability derived from its use. This study can be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Please give credit where it is due. UPDATED MASTER PLAN FOR THE CLOSURE AND REHABILITATION OF UNCONTROLLED DUMPSITES THROUGHOUT THE COUNTRY OF LEBANON Volume A JUNE 2017 Consultant (This page has been intentionally left blank) UPDATED MASTER PLAN FOR THE CLOSURE AND REHABILITATION OF UNCONTROLLED DUMPSITES MOE-UNDP UPDATED MASTER PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................................... v List of Tables .............................................................................................................................................. -

15 Places You Need to Visit to Escape Beirut's Heat! It's Super Hot out There!

15 places you need to visit to escape Beirut's heat! It's super hot out there! Grace H. · 1 week ago 0 shares When the temperature peaks, you know it's time to hit the road and visit the day3a (village)! Visit these places when you need to escape Beirut's unbearable heat! Faraya @ptk_lebanonembedded via Faraya is a small village, but a major ski destination! Restaurants, pubs, and resorts attract tourists and locals from nearby regions in summer! Chouf @anna_purplechillembedded via Chouf is a historical region in Lebanon. It is home to the 19th century Beiteddine Palace which is the President's official summer residence. While you're there, make sure to visit Moussa Castle which contains figurines that portray scenes of the village life. It also features artifacts, gemstones, clothing, and 32,000 weapons. It’s a heritage museum where you can go back in time. Read more. Bcharre @ragheb02embedded via Bcharre is a breathtaking town in Northern Lebanon. With an altitude of 1,500 meters and a population of just 24,000 people, Bcharre has quite a rich history. It is the birthplace of the famous poet Gibran Khalil Gibran. Bcharre was also the site of a Phoenician settlement in the ancient times. It is also the home of Qadisha Valley which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Zahle @livelovezahlehembedded via Zahle is full of beautiful sceneries, exciting places to visit and delicious food to try! The Berdawni Promenade is one of the top attractions of Zahle! Located along the river, the walk is filled with restaurants and cafes. -

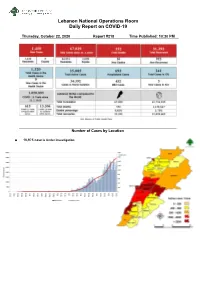

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19 Thursday, October 22, 2020 Report #218 Time Published: 10:30 PM Number of Cases by Location • 10,975 case is Under investigation Beirut 60 Chouf 43 Kesrwen 98 Matn 151 Ashrafieh 9 Anout 1 Ashkout 1 Ein Alaq 1 Ein Al Mreisseh 1 Barja 6 Ajaltoun 2 Ein Aar 1 Basta Al Fawka 1 Barouk 1 Oqaybeh 1 Antelias 3 Borj Abi Haidar 2 Baqaata 1 Aramoun 1 Baabdat 3 Hamra 1 Chhim 6 Adra & Ether 1 Bouchrieh 1 Mar Elias 3 Damour 1 Adma 1 Beit Shabab 2 Mazraa 3 Jiyyeh 2 Adonis 3 Beit Mery 1 Mseitbeh 2 Ketermaya 2 Aintoura 1 Bekfaya 2 Raouche 1 Naameh 5 Ballouneh 3 Borj Hammoud 9 Ras Beirut 1 Niha 3 Fatqa 1 Bqennaya 1 Sanayeh 2 Wady Al Zayne 1 Bouar 2 Broummana 2 Tallet El Drouz 1 Werdanieh 1 Ghazir 3 Bsalim 1 Tallet Al Khayat 1 Rmeileh 1 Ghbaleh 1 Bteghrine 1 Tariq Jdeedeh 4 Saadiyat 1 Ghodras 2 Byaqout 1 Zarif 1 Sibline 1 Ghosta 3 Dbayyeh 3 Others 27 Zaarourieh 1 Hrajel 1 Dekwene 12 Baabda 101 Others 9 Ghadir 2 Dhour Shweir 1 Ein El Rimmaneh 8 Hasbaya 6 Haret Sakher 6 Deek Al Mahdy 2 Baabda 4 Hasbaya 1 Kaslik 3 Fanar 4 Bir Hassan 1 Others 5 Sahel Alma 7 Horch Tabet 1 Borj Al Brajneh 17 Byblos 25 Sarba 5 Jal El Dib 3 Botchay 1 Blat 1 Kfardebian 1 Jdeidet El Metn 2 Chiah 6 Halat 1 Kfarhbab 1 Mansourieh 2 Forn Al Shebbak 3 Jeddayel 1 Kfour 3 Aoukar 3 Ghobeiry 3 Monsef 1 Qlei'aat 1 Mazraet Yashouh 3 Hadat 12 Ras Osta 1 Raasheen 2 Monteverde 2 Haret Hreik 5 Others 20 Safra 2 Mteileb 3 Hazmieh 4 Jezzine 12 Sehaileh 1 Nabay 1 Loueizy 1 Baysour 1 Tabarja 6 Naqqash 3 Jnah 2 Ein Majdoleen 1 Zouk Michael 1 Qanbt -

Syria Refugee Response

SYRIA REFUGEE RESPONSE Distribution of MoPH network and UNHCR Health Brochure Selected PHC as of 6 October, 2016 Akkar Governorate, Akkar District - Number of syrian refugees : 99,048 Legend !( Moph Network Moph Network !< and UNHCR Dayret Nahr Health El-Kabir 1,439 Brochure ") UNHCR Health Brochure Machta Hammoud Non under 2,246 MoPH network 30221 ! or under 30123 35516_31_001 35249_31_001 IMC No partner Wadi Khaled health center UNHCR Health Al Aaboudiyeh Governmental center !< AAridet Sammaqiye !( 713 Aaouaainat Khalsa Brochure Cheikh Hokr Hokr Dibbabiye Aakkar 1 30216 Zennad Jouret Janine Ed-Dahri 67 Kfar 6 35512_31_001 6 Srar 13 !( Aamayer Kharnoubet Noun No partner 13,361 Barcha Khirbet Er Aakkar 8 Alaaransa charity center Most Vulnerable Massaaoudiye 7 Aarme Mounjez Remmane 386 Noura ! 29 25 13 Qachlaq Et-Tahta 35512-40-01 Localities Tall Chir 28 17 Hmayra No partner Cheikh Kneisset Hmairine Aamaret Fraydes ! 105 1,317 Srar Aakkar Cheikhlar Wadi Khaled SDC Qarha Zennad Aakkar Tall El-Baykat 108 7 Rmah 62 Aandqet !< Aakkar 257 Mighraq 33 Bire 462 Most Mzeihme Ouadi 49 401 17 44 Aakkar 11 El-Haour Kouachra 168 Baghdadi Vulnerable Haytla 636 1,780 Qsair Hnaider 30226 !( Darine 10 Aamriyet Aakkar 1,002 35229_31_001 124 Aakkar 35 Mazraat 2nd Most No partner Tall Aabbas Saadine Alkaram charity center - Massoudieh Ech-Charqi 566 En-Nahriye Kneisset Tleil Barde 958 878 Hnaider Vulnerable !< 798 35416-40-01 4 Ghazayle 1,502 30122 38 No partner ! 35231_31_001 Bire Qleiaat Aain Ez-Zeit Kafr Khirbet ")!( IMC Aain 3rd Most Aakkar Hayssa Saidnaya -

A GLANCE at the WILD FLORA of MOUNT HERMON LEBANON - Beirut Arab University - Research Center for Environment and Development

Beirut Arab University Digital Commons @ BAU University Books Book Gallery 2017 A GLANCE AT THE WILD FLORA OF MOUNT HERMON LEBANON - Beirut Arab University - Research Center for Environment and Development Safaa Baydoun Beirut Arab University, Lebanon, [email protected] Nelly Apostolides Arnold Beirut Arab University, Holy Spirit of Kaslik, Saint Joseph University, Lebanon, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bau.edu.lb/university_books Part of the Biosecurity Commons, and the Plant Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Baydoun, Safaa and Arnold, Nelly Apostolides, "A GLANCE AT THE WILD FLORA OF MOUNT HERMON LEBANON - Beirut Arab University - Research Center for Environment and Development" (2017). University Books. 2. https://digitalcommons.bau.edu.lb/university_books/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Book Gallery at Digital Commons @ BAU. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Books by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ BAU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A GLANCE AT THE Authors Nelly Arnold Safaa Baydoun WILD FLORA Editing and Organizing OF Technical Office Research Center for Environment and Development MOUNT Designing Meralda M. Hamdan HERMON Publisher LEBANON Beirut Arab University, 2017 www.bau.edu.lb TABLE OF CONTENTS Forward 9 Authors 11 Acknowledgment 13 Mount Hermon 15 Lithology 15 Vegetation 17 Ecosystem Services 19 Epigraphy, Archaeology and Religious Heritage 19 Abbreviations 19 Floristic Species -

Health Services for Syrian Refugees in Mount Lebanon and Beirut

HEALTH SERVICES FOR SYRIAN REFUGEES IN MOUNT LEBANON AND BEIRUT What to do if you need to see a doctor or go to hospital and what you have to pay The information contained in this brochure was updated in May 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS IF YOU NEED TO SEE A DOCTOR .................................................................................... 3 IF YOU NEED TO GO TO HOSPITAL ................................................................................. 5 PREGNANT WOMEN ..................................................................................................... 7 CHRONIC DISEASES ........................................................................................................ 8 PHYSICAL OR MENTAL DISABILITIES ............................................................................ 10 TUBERCULOSIS ............................................................................................................. 11 HIV ............................................................................................................................... 11 LEISHMANIASIS ........................................................................................................... 12 VACCINATIONS FOR CHILDREN .................................................................................... 13 PHCs AND DISPENSARIES IN MOUNT LEBANON AND BEIRUT ..................................... 14 HOSPITALS IN MOUNT LEBANON AND BEIRUT ........................................................... 18 CONTACT NUMBERS AND HOTLINES OF PARTNERS ................................................... -

The Sweet Burden: Constructing and Contesting Druze Heritage and Identity in Lebanon

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-6-2016 The weetS Burden: Constructing and Contesting Druze Heritage and Identity in Lebanon Chad Kassem Radwan Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Radwan, Chad Kassem, "The wS eet Burden: Constructing and Contesting Druze Heritage and Identity in Lebanon" (2016). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6132 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Sweet Burden: Constructing and Contesting Druze Heritage and Identity in Lebanon by Chad Kassem Radwan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Kevin A. Yelvington, D.Phil Elizabeth Aranda, Ph.D. Abdelwahab Hechiche, Ph.D. Antoinette Jackson, Ph.D. John Napora, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 1, 2016 Keywords: preservation, discursive approach, educational resources, reincarnation Copyright © 2016, Chad Radwan Dedication Before having written a single word of this dissertation it was apparent that my success in this undertaking, as in any other, has always been the product of my parents, Kassem and Wafaa Radwan. Thank you for showing me the value of dedication, selflessness, and truly, truly hard work. I have always harbored a strong sense of compassion for each and every person I have had the opportunity to come across in my life and I have both of you to thank for understanding this most essential human sentiment. -

Public Transcript of the Hearing Held on 4 May 2015 in the Case Of

20150504_STL-11-01_T_T146_OFF_PUB_EN 1/104 PUBLIC Official Transcript Procedural Matters: (Open Session) Page 1 1 Special Tribunal for Lebanon 2 In the case of The Prosecutor v. Ayyash, Badreddine, Merhi, 3 Oneissi, and Sabra 4 STL-11-01 5 Presiding Judge David Re, Judge Janet Nosworthy, 6 Judge Micheline Braidy, Judge Walid Akoum, and 7 Judge Nicola Lettieri - [Trial Chamber] 8 Monday, 4 May 2015 - [Trial Hearing] 9 [Open Session] 10 --- Upon commencing at 10.06 a.m. 11 THE REGISTRAR: The Special Tribunal for Lebanon is sitting in an 12 open session in the case of the Prosecutor versus Ayyash, Badreddine, 13 Merhi, Oneissi, and Sabra, case number STL-11-01. 14 PRESIDING JUDGE RE: Good morning to everyone. This week we are 15 sitting to hear the evidence of Mr. Walid Jumblatt. Before we call the 16 witness into court, I'll take appearances starting with the Prosecution. 17 Good morning, Mr. Cameron. 18 MR. CAMERON: Good morning, Your Honour. It's Graeme Cameron for 19 the Prosecution assisted by Ms. Skye Winner. 20 MS. ABDELSATER-ABUSAMRA: Good morning, Your Honour. 21 Nada Abdelsater-Abusamra for the Legal Representative for the Victims 22 assisted by Kiat Wei Ng. Thank you. 23 MR. AOUN: Mr. President, Your Honours, good morning. Good 24 morning everyone in and around the courtroom. For today Thomas Hannis 25 and Emile Aoun and we represent the interests of Mr. Salim Ayyash. Thank Monday, 04 May 2015 STL-11-01 Interpretation serves to facilitate communication. Only the original speech is authentic. 20150504_STL-11-01_T_T146_OFF_PUB_EN 2/104 PUBLIC Official Transcript Procedural Matters: (Open Session) Page 2 1 you.