Training Manual. I Had the Opportunity to Discuss These Processes with the Training Director and Have Questions Answered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, et al. For Consent to Assignment of Licenses of ) BALH-20070627ACN ) BALH-20070627ACO, et al. Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; ) BAL-20070906ADP CC Licenses, LLC; AMFM Radio ) BALH-20070906ADQ Licenses, LLC; Citicasters Licenses, LP; ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; and ) Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. ) Federal Communications Commission ERRATUM Released: January 30, 2008 By the Media Bureau: On January 24, 2008, the Commission released a Memorandum Opinion and Order(MO&O),FCC 08-3, in the above-captioned proceeding. -

2018 ANNUAL REPORT BOARD of DIRECTORS 2017-2018 Chairman Robert M

2018 ANNUAL REPORT BOARD OF DIRECTORS 2017-2018 Chairman Robert M. Boyd, Virginia Beach Chairman Elect Cyrus W. Grandy V, Norfolk Secretary Naomi Muellner, Virginia Beach Executive Director Robert W. Cross, Norfolk Members at Large Clay H. Barr, Norfolk Alan G. Bartel, Virginia Beach Lisa F. Chandler, Norfolk David M. Delpierre, Norfolk Leslie E. Doyle, Norfolk John Field, Courtland Paul D. Fraim, Norfolk Martha Goode, New York City Howard Gordon, Virginia Beach Susan Hirschbiel, Virginia Beach James A. Hixon, Virginia Beach Connie Jacobson, Norfolk Maurice A. Jones, Norfolk James M. LaVier III, Virginia Beach John P. Matson, Virginia Beach Merrick McCabe, Virginia Beach Pat Richardson, Virginia Beach Thomas V. Rueger, Virginia Beach Burrell Saunders, Norfolk Bert Schmidt, Norfolk André-Michel Schub, New York City Simon H. Scott, Norfolk Lauren Sparks, Virginia Beach Wayne F. Wilbanks, Norfolk STAFF Executive Director/Perry Artistic Director Robert W. Cross General Manager J. Scott Jackson ADMINISTRATION Volunteer Coordinator: Sandy Miller Associate Director of Programming: Kimberly Schuette Pops Programming Manager: Rudi Schlegel Executive Assistant: Kelly Loer Executive Assistant: Tracy Uriegas Special Projects: JoAnn Cross Office Coordinator: Mary Hasan Front Desk Assistants: Kathleen Apelt, Leslie Rainey, Charlina Spruill Courier: Wesley Smith BOX OFFICE Director of Ticketing: Kari Esther Pincus Box Office Supervisor: Jeffrey Gallo Associates: Whitney Edwards, Chris George, Kylie Joiner, Scherry MacCartney, Sandra Wirth DEVELOPMENT -

WHRO-TV, WHRO-FM, WHRV Diversity Policy 2014

WHRO-TV, WHRO-FM, WHRV-FM DIVERSITY POLICY Statement of Commitment to Diversity WHRO Public Media establishes the policy to promote diversity in our workforce, management and boards, including our community advisory boards and governing boards. Board Resolution was adopted by the WHRO Governing Board September 11, 2012. The integrity of our work is strengthened by incorporating the diversity of demography, culture, and beliefs in our communities and the nation into our work and our content. We look to the full diversity of our community as we ascertain needs and interest to which we might respond. We assure that people with different backgrounds, perspectives, and experience are heard and seen as both sources and subjects of our programming and are invited to participate in our activities. We seek to create content and activities that reach and serve a diversity of people, recognizing that different programming attracts people with different values, beliefs, lifestyles, and demography. We treat the subjects of our programming with respect. We include points of view that may not be widely shared and individual and groups that are infrequently heard or seen outside their own communities. WHRO Public Media Diversity Goals • It is our policy to provide equal employment opportunity to all qualified individuals without regard to race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, physical ability, marital status, veteran status, and national and geographic origin in all personnel actions including recruitment, evaluation, selection, promotion, compensation, training and termination. • It is our policy to communicate our equal employment policy and employment needs to sources of qualified applicants, without regard to race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, religion, socio-economic status, physical ability, marital status, veteran status, and national and geographic origin and to solicit their recruitment assistance on a continuing basis. -

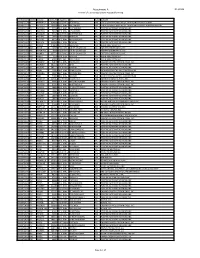

VAB Member Stations

2018 VAB Member Stations Call Letters Company City WABN-AM Appalachian Radio Group Bristol WACL-FM IHeart Media Inc. Harrisonburg WAEZ-FM Bristol Broadcasting Company Inc. Bristol WAFX-FM Saga Communications Chesapeake WAHU-TV Charlottesville Newsplex (Gray Television) Charlottesville WAKG-FM Piedmont Broadcasting Corporation Danville WAVA-FM Salem Communications Arlington WAVY-TV LIN Television Portsmouth WAXM-FM Valley Broadcasting & Communications Inc. Norton WAZR-FM IHeart Media Inc. Harrisonburg WBBC-FM Denbar Communications Inc. Blackstone WBNN-FM WKGM, Inc. Dillwyn WBOP-FM VOX Communications Group LLC Harrisonburg WBRA-TV Blue Ridge PBS Roanoke WBRG-AM/FM Tri-County Broadcasting Inc. Lynchburg WBRW-FM Cumulus Media Inc. Radford WBTJ-FM iHeart Media Richmond WBTK-AM Mount Rich Media, LLC Henrico WBTM-AM Piedmont Broadcasting Corporation Danville WCAV-TV Charlottesville Newsplex (Gray Television) Charlottesville WCDX-FM Urban 1 Inc. Richmond WCHV-AM Monticello Media Charlottesville WCNR-FM Charlottesville Radio Group (Saga Comm.) Charlottesville WCVA-AM Piedmont Communications Orange WCVE-FM Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corp. Richmond WCVE-TV Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corp. Richmond WCVW-TV Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corp. Richmond WCYB-TV / CW4 Appalachian Broadcasting Corporation Bristol WCYK-FM Monticello Media Charlottesville WDBJ-TV WDBJ Television Inc. Roanoke WDIC-AM/FM Dickenson Country Broadcasting Corp. Clintwood WEHC-FM Emory & Henry College Emory WEMC-FM WMRA-FM Harrisonburg WEMT-TV Appalachian Broadcasting Corporation Bristol WEQP-FM Equip FM Lynchburg WESR-AM/FM Eastern Shore Radio Inc. Onley 1 WFAX-AM Newcomb Broadcasting Corporation Falls Church WFIR-AM Wheeler Broadcasting Roanoke WFLO-AM/FM Colonial Broadcasting Company Inc. Farmville WFLS-FM Alpha Media Fredericksburg WFNR-AM/FM Cumulus Media Inc. -

Unforgettable Experiences Inside! Welcome

2019 ROBERT W. CROSS PERRY ARTISTIC DIRECTOR KRISTIN CHENOWETH VIRGINIA INTERNATIONAL TATTOO OLGA KERN PILOBOLUS ©Chris Nash VAFEST.ORG UNFORGETTABLE EXPERIENCES INSIDE! WELCOME Dear Friends, There is so much to celebrate in our 2019 Festival season! This season of “firsts” welcomes artists new to the Festival including Broadway star Kristin Chenoweth, cabaret legend Michael Feinstein, the phenomenal Jessica Lang Dance company, and renowned classical music artists, along with a slate of premieres, including the world premiere TICKETS ON SALE NOW! performances of new works from Dance Theatre of Harlem and Richard Alston Dance Company, The more you buy, the more you save! commissioned by the Festival through our partnership Choose 3 performances and save 10%...choose with the 2019 Commemoration, American Evolution™. GUIDE TO 2019 This season also marks an exciting new beginning for 4 or more performances and save 15%! PERFORMANCES & EVENTS our chamber music programs, with the arrival of our new Connie & Marc Jacobson Director of Chamber Music, Van Cliburn Gold Medalist Olga Kern, who has curated a brilliant chamber music series featuring Best of Broadway ..................................... 3 artists new to the Festival; one of the world’s great Chamber Music Concerts ................ 4-5 pianists, she will also perform a thrilling solo recital. Order online and choose your own seats! Coffee Concerts ....................................6-7 I’m particularly excited about our presentation — the East Coast premiere — of Shakespeare’s Antony Classical Music Series ........................ 8-9 and Cleopatra, in a production originally created VAFEST.ORG Dance Series .......................................10-12 by Shakespeare’s Globe in London; this exciting performance will feature the Virginia Symphony Vocal Series ................................................13 Orchestra conducted by JoAnn Falletta. -

This Administrative and Professional Faculty Handbook Was Approved by the Board of Visitors on December 14, 2001

This Administrative and Professional Faculty Handbook was approved by the Board of Visitors on December 14, 2001. This handbook covers all NSU employees hired as administrative and professional faculty. Effective January 1, 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................1 History..................................................................................................................................1 Accreditation ........................................................................................................................2 University Mission ...............................................................................................................2 ADMINISTRATIVE STRUCTURE ............................................................................................3 Board of Visitors ..................................................................................................................3 President ...............................................................................................................................3 Executive Assistant to the President and Agency Legislative Liaison ................................3 Vice President for Academic Affairs ...................................................................................4 Vice President for Advancement .........................................................................................4 Vice President for Finance and Business -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

Attachment a DA 19-526 Renewal of License Applications Accepted for Filing

Attachment A DA 19-526 Renewal of License Applications Accepted for Filing File Number Service Callsign Facility ID Frequency City State Licensee 0000072254 FL WMVK-LP 124828 107.3 MHz PERRYVILLE MD STATE OF MARYLAND, MDOT, MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMN. 0000072255 FL WTTZ-LP 193908 93.5 MHz BALTIMORE MD STATE OF MARYLAND, MDOT, MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 0000072258 FX W253BH 53096 98.5 MHz BLACKSBURG VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072259 FX W247CQ 79178 97.3 MHz LYNCHBURG VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072260 FX W264CM 93126 100.7 MHz MARTINSVILLE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072261 FX W279AC 70360 103.7 MHz ROANOKE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072262 FX W243BT 86730 96.5 MHz WAYNESBORO VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072263 FX W241AL 142568 96.1 MHz MARION VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072265 FM WVRW 170948 107.7 MHz GLENVILLE WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072267 AM WESR 18385 1330 kHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072268 FM WESR-FM 18386 103.3 MHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072270 FX W289CE 157774 105.7 MHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072271 FM WOTR 1103 96.3 MHz WESTON WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072274 AM WHAW 63489 980 kHz LOST CREEK WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072285 FX W206AY 91849 89.1 MHz FRUITLAND MD CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. 0000072287 FX W284BB 141155 104.7 MHz WISE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072288 FX W295AI 142575 106.9 MHz MARION VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072293 FM WXAF 39869 90.9 MHz CHARLESTON WV SHOFAR BROADCASTING CORPORATION 0000072294 FX W204BH 92374 88.7 MHz BOONES MILL VA CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. -

EEO Public File Report for 2021

EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT FOR WHRO-TV, WHRO-FM, WHRV(FM) Norfolk, Virginia This EEO Public File Report June 1, 2020 – May 31, 2021 EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT This EEO Public File Report is filed in Station WHRO public inspection file pursuant to Section 73.2080(c) (6) of the Federal Communication’s (“FCC”) rules. During the twelve month period ending on May 31, 2021, the station filled the following full-time vacancies: Assistant to the PresiDent* Virtual Virginia E-Learning Support Specialist* Grants anD Initiatives Manager Multi MeDia Marketing ProDucer Animator Social MeDia Specialist News Director Senior StuDio Engineer NOTE: The contract with WHRO’s ATS System, ClearCompany, useD for recruiting anD tracking applicant anD hiring Data enDeD September 30, 2020. August 2020 WHRO starteD using the ATS through PayCom, the proviDer of our payroll services. It was DiscovereD several month later after several postings that there was a glitch in the system anD the positions inDicateD above with the * DiD not post to the recruitment sites built into the recruiting system which incluDes InDeeD, Resume.com, GlassDoor anD Simply HireD. The station interviewed a total of 33 applicants for all full-time vacancies during the period covered in this report. The following are the recruitment sources used during the period covered in this report and the cumulative number of interviewees referred by each: Recruitment Source Total Number of Interviewees ReferreD WHRO Career Website 7 Indeed 2 Resume.com GlassDoor Simply Hired Current 1 NABJ Career Center Virginia -

1401 – Inclement Weather/Emergent Hazardous Conditions

No. 1401 Rev.: 1 Policies and Procedures Date: September 5, 2013 Subject: Inclement Weather/Emergent Hazardous Conditions 1. Purpose .................................................................................................................... 1 2. Policy ........................................................................................................................ 2 2.1. College Closings ............................................................................................... 2 2.2. Campus and Off-Campus Location Closings .................................................... 2 2.3. Closings at Non-TCC Locations ....................................................................... 3 2.4. Notification ........................................................................................................ 3 2.5. Designated Personnel ...................................................................................... 3 2.6. Academic Schedule .......................................................................................... 4 2.7. Compensation .................................................................................................. 4 2.8. Compliance ...................................................................................................... 4 3. Responsibilities ......................................................................................................... 4 4. Procedures .............................................................................................................. -

City of Newport News VPDES Permit VA 0088641

City of Newport News VPDES Permit VA 0088641 ANNUAL REPORT Period: July 1, 2013 - June 30, 2014 Department of Engineering TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE 1 Contents of Program A. Stormwater Management Program ....................................................... B. Special Conditions................................................................................. C. SWMP Effectiveness Indicators ........................................................... 2 Program Modifications Requested By Permittee ........................................................................ 2-1 Requested By DEQ ............................................................................... 2-1 3 Annual Report Annual Report Outline ......................................................................... 3-1 Implementation of Program Components ............................................. 3-2 Proposed Program Changes .................................................................. 3-6 Revision to Assessment of Controls ..................................................... 3-6 Summary of Effectiveness Indicators ................................................... 3-7 Annual Expenditures ............................................................................. 3-9 Summary of Enforcement, Inspections and Public Education ........... 3-10 Water Quality Improvements or Degradation .................................... 3-12 Cooperative or Multi-Jurisdictional Activities ................................... 3-14 Annual Nutrient Loadings ................................................................. -

Entercom Richmond Congratulates Wes Mcelroy As Virginia Sportscaster of the Year

ENTERCOM RICHMOND CONGRATULATES WES MCELROY AS VIRGINIA SPORTSCASTER OF THE YEAR RICHMOND, VA – January 20, 2018 – Entercom, the #1 creator of live, original, local audio content in the United States, announced that Wes McElroy of Fox Sports 910 has been chosen as the Virginia Sportscaster of the Year by The National Sports Media Association. "It's a real career thrill to be named Virginia Sports Broadcaster of the Year for the second time in four years,” said McElroy, who hosts mornings on Fox Sports 910 and is celebrating his 10th year on the air in Richmond. “What means the most is, it's an award voted on by my colleagues in the Virginia sports media. To have this distinguished honor from a collection of men and women that I respect is what makes this a highlight of my career." McElroy is also a co-host for the Virginia Tech IMG Sports Network, hosts the Hokies Post Game Live, is the studio host for VCU Basketball and writes the weekly column “What I learned in Sports this Week,” that appears in the Richmond Times Dispatch. Entercom owns and operates WRVA-AM, WRNL-AM, WRVQ-FM, WTVR-FM, WRXL-FM, WBTJ-FM, WRVQ-HD2 and WRXL-HD2 in Richmond. Fans can listen to WRVA-AM online via the radio.com app nationwide. Fans can also engage with the station via Facebook and Twitter. Entercom is a leading American media and entertainment company and one of the top two radio broadcasters in the country. Entercom is the nation’s unrivaled leader in news and sports radio.