Review Materials AP EURO

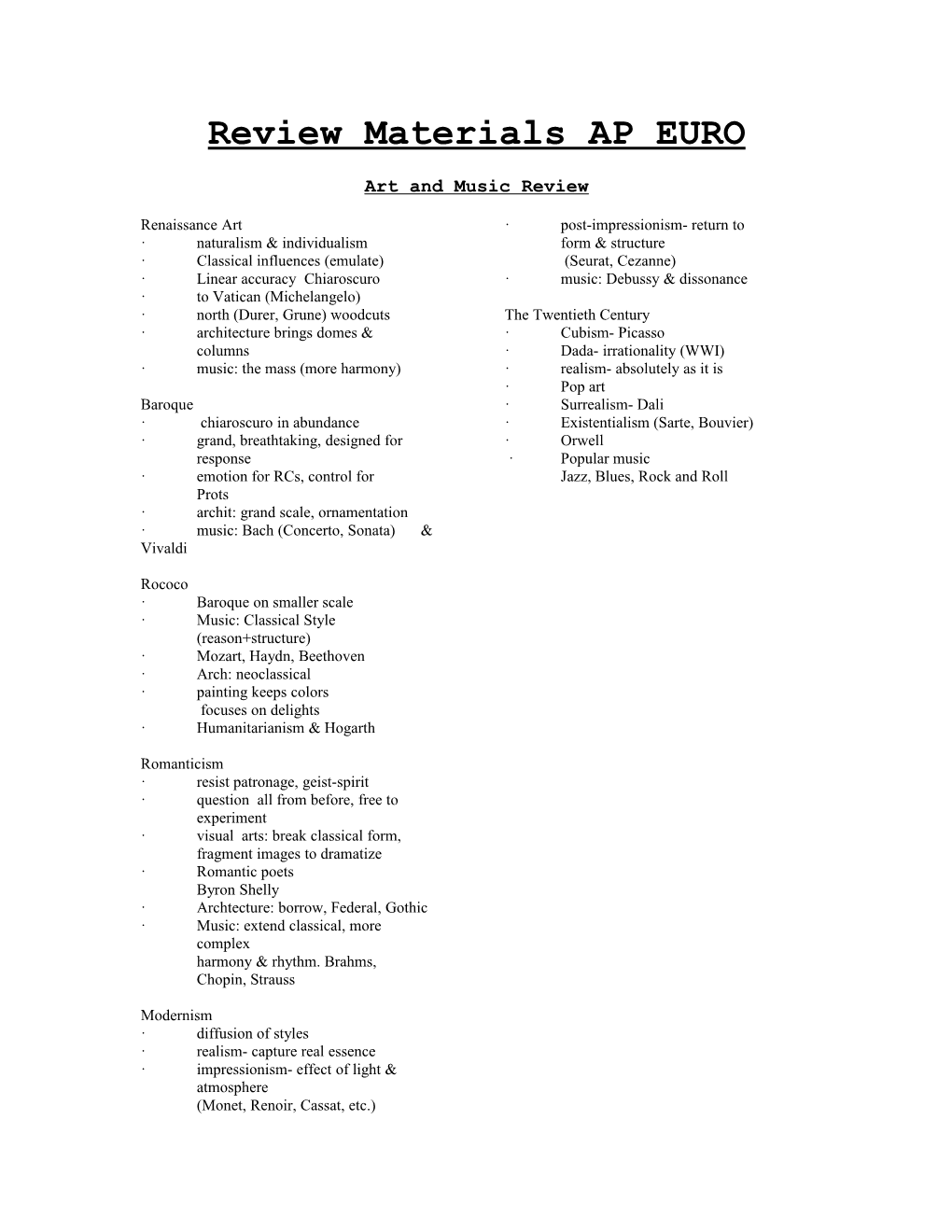

Art and Music Review

Renaissance Art · post-impressionism- return to · naturalism & individualism form & structure · Classical influences (emulate) (Seurat, Cezanne) · Linear accuracy Chiaroscuro · music: Debussy & dissonance · to Vatican (Michelangelo) · north (Durer, Grune) woodcuts The Twentieth Century · architecture brings domes & · Cubism- Picasso columns · Dada- irrationality (WWI) · music: the mass (more harmony) · realism- absolutely as it is · Pop art Baroque · Surrealism- Dali · chiaroscuro in abundance · Existentialism (Sarte, Bouvier) · grand, breathtaking, designed for · Orwell response · Popular music · emotion for RCs, control for Jazz, Blues, Rock and Roll Prots · archit: grand scale, ornamentation · music: Bach (Concerto, Sonata) & Vivaldi

Rococo · Baroque on smaller scale · Music: Classical Style (reason+structure) · Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven · Arch: neoclassical · painting keeps colors focuses on delights · Humanitarianism & Hogarth

Romanticism · resist patronage, geist-spirit · question all from before, free to experiment · visual arts: break classical form, fragment images to dramatize · Romantic poets Byron Shelly · Archtecture: borrow, Federal, Gothic · Music: extend classical, more complex harmony & rhythm. Brahms, Chopin, Strauss

Modernism · diffusion of styles · realism- capture real essence · impressionism- effect of light & atmosphere (Monet, Renoir, Cassat, etc.) Authors

CERVANTES SAAVEDRA, Miguel de Born: September 29, 1547Died: April 23, 1616

It was while in prison, however that Cervantes first conceived of the allegorical story of the adventures of Don Quixote, an idealistic gentleman obsessed with chivalrous deeds, and his realistic companion Sancho Panza. In 1605, the year when the first part of the story, The History of the Valorous and Wittie Knight-Errant Quixote of the Mancha, was published, Cervantes was living in poverty with his sisters, his niece and his illegitimate daughter Isabel Saavedra in Valladolid. Unfortunately while the story and its subsequent second part were immensely popular at the times of their publication and ever since, Cervantes did not ever profit significantly from the text, partly from poor management.

Don Quixote is deemed by many to be the first modern novel, holding a position of significant influence on ensuing prose fiction. Its enduring themes have since inspired, and have been represented in, operas, poems, films, a ballet and a modern day American musical (Man of La Mancha), as well as in the artwork of Honore Daumier and Gustave Dore. In print it has appeared in all modern languages, in over 700 editions.

In 1613 Cervantes published Novelas Ejemplares, a collection of short stories, followed by the second part of Don Quixote in 1615. His last work, Persiles y Sigismunda, another allegorical novel in whose prologue he foreshadows his own death, was finished just four days before he died in Madrid.

DICKENS, CharlesBorn: February 7, 1812Died: June 9 1870, in Gadshill, London, England

Charles Dickens, who often used the pseudonym Boz, was the most popular English novelist and short- story writer of all time. His novels reflect his own experiences as a poor child in London and Kent. Because his father was imprisoned for debts, Dickens was forced into work at the age of nine. Although he attended school for two years, he was mostly self-educated. His work is heavily influenced by the works of his favourite authors, Henry Fielding and Tobias Smollett. He also loved to read Gothic novels.

With the success of Sketches by Boz, published in 1836, he married Catherine Hogarth. The couple stayed together for twenty-two years and had ten children. However, they eventually separated over Dickens' relationship with actress Ellen Ternan.

Like Sketches by Boz, Dickens continued to write a monthly series of comic vignettes with the Pickwick Papers. Critics feel that, because the works were published as a series, Dickens' work is less coherent than it might have been if he had been allowed to write his texts as more unifed entities.

With Dombey and Son and Oliver Twist, Dickens' style began to move away from comedy toward darker themes. He was one of the first to experiment with the use of symbolism to heighten narrative (for example, foggy streets were used to foreshadow an ominous event).

The most emphasis, however, has been placed on the works that Dickens wrote in the late period, such as Hard Times in 1854, Tale of Two Cities in 1859, and Great Expectations in 1861. At this time, Dickens' had developed his own unique style and was a master at depicting the human condition.

During his life, Dickens remained involved in humanitarian causes. He was involved in many charities and advocated the abolition of slavery. A stroke caused his death in 1870 and he was buried at Westminster Abbey. DOSTOEVSKY, Fyodor Mikhailovich)Born: November 11, 1821 Died: February 9, 1881

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevesky was born in Moscow to impoverished parents. While his father was descended from the Russian nobility and his mother was from a wealthy merchant family, the political upheaval in Russia had reduced them to the economic status of the working class.

Dostoevesky's father worked at a hospital for the poor, and consequently the family, including Dostoevesky's four brothers and two sisters, lived on the hospital grounds. With sickness and death around him, Dostoevesky developed a familiarity with human suffering that may have prepared him for the tragedies he would experience throughout his life.

Dostoevesky's first novel, Poor Folk, was published in 1846 and at this time, he began to associate with a secret revolutionary group called the Petrashevski Circle. As a result, he was arrested and imprisoned for conspiracy. He was imprisoned for four years and spent another four years in the Siberian Army before being released. The physical hardships and poor living conditions contributed to his problems with epilepsy which would continue to plague him for the rest of his life.

The novel Crime and Punishment was published in 1866. It was immediately popular and Dostoevesky's fame spread quickly throughout Russia. However, it wasn't until the book's translation into English, after his death, that he achieved much of a reputation outside of Russia. Crime and Punishment, a story of sin, suffering and redemption, was Dostoevesky's first successful novel since his imprisonment and it reflected his changed attitudes. The liberal attitudes of youth had been replaced by the more conservative attitudes of the middle-aged.

Dostoevesky's last work, and also one of his greatest, was The Brothers Karamazov. Within the context of a tragedy, the story includes tales of prophecy, abstract philosophical discussions, and psychological analysis of human nature. Following the style of Crime and Punishment, The Brothers Karamazov is occasionally wordy and rarely offers solutions but perpetually raises disturbing questions.

Much of Dostoevesky's writing focuses on the topic of morality, and frequently, within the context of crime, explores acts of transgression or an investigation of the religious experience. While he never completely resolved the questions his writing raised, he professed the belief that a person, guilty of an evil act, could be cleansed through suffering.

GOETHE, Johann Wolfgang vonBorn: August 28, 1749, Died: March 22, 1832

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was a poet, dramatist, philosopher, scientist and a leader of the German intellectual renaissance of the late eighteenth century. He is noted for his ability to understand human individuality and expresses a modern view of humanity's relationships.

Goethe's most noted work is Faust, which he published only a year before his death. Based on the legends of a wandering magician, Faust is an enduring work that attempts to understand the existence of man. The work has been translated numerous times, but the most influential were the translations completed by the English poet Carlyle. Through Carlyle, Goethe influenced a generation of Victorian writers.

HUGO, VictorBorn: February 26, 1802, Died: May 22, 1885, in Paris

Victor Hugo was a prolific French poet, novelist, and playwright. He is noted for his contributions to romantic movement. In France, he is best remembered for his poetry while in North America, he is remembered for his novels.

With the success in 1831 of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Hugo became a prominent social figure in France, was elected to the French Academy in 1841, and was raised to the Chamber of Peers in 1845. Over time, he gradually shifted his political views away from Napoleon's side. He produced little during this time, due to his active political life and the shock over the drowning deaths of his daughter and son-in-law.

Because of his opposition to Napolean, Hugo was exiled for nineteen years when Napolean obtained power in 1851. He spent most of his time in the Channel Islands, taking both his family and his mistress, Juliette, with him. During the exile, he was extremely productive, publishing both poetry and three novels. The best known of these novels is Les Misérables, which sold over seven million copies by the end of the century. His wife died in 1868. Hugo returned to Paris in 1870 and continued an active life until his death in 1885.

JOYCE, James Augustine AloysiusBorn: February 2, 1882 Died: January 13, 1941,

It was the 1922 publication of his next work, Ulysses, however, which brought Joyce international fame. In this text based on the themes of Homer's Odyssey, Joyce further developed his characteristic use of symbols and 'stream of consciousness' writing which he had used in his earlier book Portrait. This technique, which involved 'recording' all the thoughts and feelings of a character, was a significant development for realist fiction and character portrayal. The book follows a day in the life of two characters who eventually meet. Ulysses received a widely varied and at times violent reception; while some felt the book depicted a rather squalid existence in Dublin, others felt the book explored fundamental human feelings and experiences.

Joyce continued writing and published two more collections of verse (Pomes Penyeach and Collected Poems) before his last and most complex work, Finnegan's Wake, was published in 1939. He furthered his experimentation with language in this book, attempting to represent in fiction a cyclical theory of history. Joyce died in 1941 in Zurich, where after living in Paris for twenty years, he had moved when Germans invaded France during World War II.

KEATS, JohnBorn: October 29 (or 31), 1795 Died: February 23, 1821

Keats is widely regarded as the most talented of the immortal English romantic poets. Of all the words he wrote, the most ironic exist in his epitaph: "Here lies one whose name was writ in water."

Once again his schoolmate, Clarke, helped Keats in the capital. Clarke showed Keats' verses to Leigh Hunt, the influential publisher and editor. Hunt was known for championing young authors and introduced Keats and his contemporary, Shelley, to the public. Keats' first important poem, On First Looking into Chapman's Homer was published in Leigh Hunt's newspaper, The Examiner, in 1815.

However, the association with Hunt proved detrimental. The reviews of Keats' first anthology, Poems published in 1817, labeled his poetry as Cockney. In fact the entire circle of young poets Hunt was promoting was unfavorably portrayed as members of the Cockney School, indicating the lower class from which they came. Keats' poetry eventually won over many of these critics but his humble background was an impediment he would constantly struggle with for the rest of his career.

After the publication of his first book, which was considered to be promising, but immature, he settled on the Isle of Wight and began work on Endymion, published in 1818. It is considered the most classical of Keats' work. It displays many of the traits of Greek art in a time of its a renaissance in England.

Following Endymion, Keats explored the Scottish highlands on foot, accompanied by his friend Charles Armitage Brown. That summer Keats developed tuberculosis. He may have come in contact with the disease from his brother Tom who died late in 1818.

After Tom's death, and his other brother George and his wife had moved to America, Keats went to live with Brown at Hampstead and began work on Hyperion. During his stay at Hampstead Keats succumbed to advanced stages of tuberculosis and love. As Dante was inspired by Beatrice Portinari, Keats was inspired by Fanny Brawne. The seventeen year old beauty lived nearby, and continues to live in his love poems such as The Eve of St. Agnes, La Belle Dame sans Merci, and the ode To a Nightingale. His passion spawned other poems such as On a Grecian Urn, To Psyche, and On Melancholy.

In February 1820 he realized he was dying and published his final work, Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems. In September, he sailed for Rome with his friend and artist, Joseph Severn. He died there and was buried in the Roman Protestant cemetery. KIPLING, RudyardBorn: December 30, 1865 Died: January 18, 1936

Kipling was a British journalist and author who is best known for his tales of adventure. He was the first Englishman awarded the Nobel Prize for literature.

His first publication, Departmental Ditties in 1886, was consumed chiefly in England by an audience eager for impressions of the savage Indian subcontinent as viewed from a distance. With the release of Plain Tales From the Hills in 1888 he seemed destined for greatness. The Light that Failed, published in 1890, was also successful, and Kim, published in 1901, is generally considered his masterpiece.

Kipling's India has often been called England's India. Through his writings he expressed optimistic notions of colonialism. He believed the responsibility of England was to oversee under- developed countries. He justified for many what has been called the "white man's burden," and showed how it could be efficiently implemented with dignity.

He was a prolific and consistent writer pouring out works for young audiences such as The Jungle Books in 1894 and 1895, Captains Courageous in 1897, and The Just-So Stories in 1902. Rather than categorizing his work it is more useful to regard Kipling's talent as lying in his ability to master a number of genres.

He received many honors such as the doctor of law degree from McGill University in 1899, the doctorate of letters from Oxford in 1907, and from Cambridge a year later. Further, in 1907 he became the first Englishman to win the Nobel Prize for literature. It confirmed his greatness was recognized beyond the confines of the English- speaking world.

MILTON, JohnBorn: December 9, 1608 Died: November 8, 1674

John Milton is considered by some the greatest English writer after Shakespeare. He worked during the transition between the Elizabethan and Jacobite periods.

Following his graduation with a master of arts in 1632, Milton spent several years living with his parents. During this time, he attacked the clergy in Lycidas and met Galileo while traveling through Italy. In 1643, he married Mary Powell. They separated within a few weeks, but reconciled years later. Together, they had three children before Powell's death in 1652. Several essays resulted from his marital problems, including The Doctrine And Discipline Of Divorce.

Milton was actively involved in the government. He wrote propaganda pieces against King Charles I and became a translator of diplomatic correspondence for Oliver Cromwell. He married Katherine Woodcock in 1656 and, after Katherine's death, Elizabeth Minshull in 1663.

He became blind later in his career, but this did not stop him from writing the epic poem, Paradise Lost, which was published in 1667. This is considered the greatest epic poem in modern literature. The work was influenced by the writings of Homer and Virgil and borrowed mythical figures such as Prometheus.

For two hundred years, Paradise Lost was considered a comprehensive theological interpretation of the bible. Today, it is used as the best poetic synthesis of Christianity. Milton followed this work with two similar poems: Paradise Regained and Samson Agonistes.

Milton died of gout and was buried beside his father in St. Giles, Cripplegate.

SHELLEY, Mary WollstonecraftBorn: August 30, 1797 Died: February 1, 1851

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley is best noted for the popular and time-honored novel, Frankenstein. Although she wrote other novels, travel journals, and verse, none of her works achieved the same success as this terrifying novel.

Wollstonecraft's novel, Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus, was published about this time in 1818. Even though Wollstonecraft was only twenty at the time she wrote the novel, it was both a popular and critical success, and continues to be represented in film and theater productions. Many interpretations of the novel exist, but when viewed in terms of Wollstonecraft's life, the story depicts the cruelty of a society that persecutes outcasts. In 1822, days before Shelley's thirtieth birthday, he drowned while sailing his boat the Don Juan. Mary edited his Posthumous Poems and Poetical Works for publication in 1824 and 1839, respectively. Although her finances were secure after she received the inheritance of her father-in-law, Timothy Shelley, she did not have the strength to complete a planned project of her husband's biography.

TENNYSON, Alfred, LordBorn: August 6, 1809 Died: October 6, 1892

Lord Alfred Tennyson is recognized as a great Victorian and Romantic era poet. His style of poetry is extremely diversified. His work was influenced by the writings of Lord Byron.

His first major work, Poems, Chiefly Lyrical, was published in 1830, the same year that he joined the Spanish revolutionary army. Two years later, he published his second work, Poems, which included well-known pieces such as The Lady of Shallot. Disturbed by the death of his close friend, Arthur Hallman, Tennyson published virtually no work for the next ten years. He did, however, start working on a tribute to Hallman. In Memoriam was published in 1850 and is one of his greatest poems.

A two-volume work, Poems was published in 1842, ending his literary silence. With this publication came popularity among the public. About this time, Tennyson published The Princess, a work that advocates women's rights.

TOLSTOY, LeoBorn: August 28, 1828 Died: November 7, 1910

Tolstoy, a Russian author and moral philosopher, is considered one of the world's greatest novelists. He is known as the master of the realistic psychological novel. His doctrines of non-violence profoundly influenced Mahatma Gandhi, among others, and eventually a new sect of Christianity known as Tolstoyism evolved.

With a structure regarded by many as perfect, War and Peace combines complex characters in a turbulent historical setting. It is regarded as one of the most influential books on the Western novel because of its great technical achievements.

Tolstoy followed this with another major novel, Anna Karenina during 1873-1876. It is the story of the tragic love of Anna Karenina, and, concurrently, a philosophy of life dramatized through the happy marriage of Konstantin Levin. Anna Karenina continues on moral themes Tolstoy raised in War and Peace. In this book he breached the topic of the ultimate meaning and purpose of human existence.

His views on religion and social reform are articulated in A Confession, written from 1878-1879 and published in 1882, and What is Art? published in 1897. Tolstoy said he endured spiritual crisis in his search for an answer to the meaning of life. Eventually he turned to a form of Christian anarchism and devoted himself to social reform. He believed the role of art was to foster the moral good among humanity. In the later text he developed an aesthetic system, later known as Tolstoyism, that gave art a religious and moral function.

He continued his ethical search for truth in a number of masterpieces such as The Death of Ivan Ilyich, The Kreutzer Sonata, Master and Man, and his last great novel, The Resurrection. Never didactic, his works stand on could stand on their creative merits alone. Among his massive collection of writings he also mastered the genre of drama with the play The Power of Darkness in 1888.

The last twenty years of Tolstoy's life were acted out under the spotlight of his own ethics. After trying to live up to his own teachings and often quarreling with his wife because of them, he eventually left home after a argument and died of pneumonia two days later. A literary giant and a moral pillar he died alone in the remote railway station in Astapovo.

VERNE, JulesBorn: February 8, 1828 Died: March 24, 1905

The popularity of his first real success, Five Weeks in a Balloon, published in 1863, inspired Verne to begin writing the works that would make him the father of science fiction. His novels complemented the rising late nineteenth century fascination with science and invention. They make extraordinary predictions about future scientific or technological developments. Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, published in 1870, for example, familiarized the reader with the submarine long before such watercraft were invented. Motion pictures, helicopters, and even air conditioning are other achievements that he forecast in his books. Although often neglected by literary scholars, Jules Verne attained a tremendous following. Novels such as Journey to the Center of the Earth, published in 1864, and Around the World in Eighty Days, published in 1873, gained him worldwide popularity and, in 1892, the French government made him a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor.

WOLLSTONECRAFT, MaryBorn: April 27, 1759 Died: September 10, 1797

Upon returning to London to once again work for Johnson, Wollstonecraft became involved with the intellectual group which included Thomas Paine, William Blake, William Woodsworth and Henry Fuseli. The group also included William Godwin, whom she married in 1797. The union was a brief one however, as shortly after the birth of their daughter Mary (later to become the author of Frankenstein), Wollstonecraft died of septicemia. Her text Vindication of the Rights of Woman, however, lives on as a classic and as one of the earliest examples of feminist theory. Thinkers

Science

Copernican system, first modern European theory of planetary motion that was heliocentric, i.e., that placed the sun motionless at the center of the solar system with all the planets, including the earth, revolved around it. Copernicus developed his theory in the early 16th cent. from a study of ancient astronomical records. He retained the ancient belief that the planets move in perfect circles and therefore, like Ptolemy, he was forced to utilize epicycles to explain deviations from uniform motion (see Ptolemaic system). Thus, the Copernican system was technically only a slight improvement over the Ptolemaic system. However, making the solar system heliocentric removed the largest epicycle and explained retrograde motion in a natural way. By liberating astronomy from a geocentric viewpoint, Copernicus paved the way for Kepler's laws of planetary motion and Newton's embracing theory of universal gravitation, which describes the force that holds the planets in their orbits.

Ptolemaic system Pronounced As: tolmaik , historically the most influential of the geocentric cosmological theories, i.e., theories that placed the earth motionless at the center of the universe with all celestial bodies revolving around it (see cosmology). The system is named for the Greco-Egyptian astronomer Ptolemy (fl. 2d cent. A.D.); it dominated astronomy until the advent of the heliocentric Copernican system in the 16th cent.

Kepler's laws, three mathematical statements formulated by the German astronomer Johannes Kepler that accurately describe the revolutions of the planets around the sun. Kepler's laws opened the way for the development of celestial mechanics, i.e., the application of the laws of physics to the motions of heavenly bodies. His work shows the hallmarks of great scientific theories: simplicity and universality. Summary of Kepler's Laws The first law states that the shape of each planet's orbit is an ellipse with the sun at one focus. The sun is thus off-center in the ellipse and the planet's distance from the sun varies as the planet moves through one orbit. The second law specifies quantitatively how the speed of a planet increases as its distance from the sun decreases. If an imaginary line is drawn from the sun to the planet, the line will sweep out areas in space that are shaped like pie slices. The second law states that the area swept out in equal periods of time is the same at all points in the orbit. When the planet is far from the sun and moving slowly, the pie slice will be long and narrow; when the planet is near the sun and moving fast, the pie slice will be short and fat. The third law establishes a relation between the average distance of the planet from the sun (the semimajor axis of the ellipse) and the time to complete one revolution around the sun (the period): the ratio of the cube of the semimajor axis to the square of the period is the same for all the planets including the earth.

Galileo

Galileo Galilei) Pronounced As: galilo; gälleo gälle , 1564-1642, great Italian astronomer, mathematician, and physicist. By his persistent investigation of natural laws he laid foundations for modern experimental science, and by the construction of astronomical telescopes he greatly enlarged humanity's vision and conception of the universe. He gave a mathematical formulation to many physical laws.

Contributions to Physics His early studies, at the Univ. of Pisa, were in medicine, but he was soon drawn to mathematics and physics. It is said that at the age of 19, in the cathedral of Pisa, he timed the oscillations of a swinging lamp by means of his pulse beats and found the time for each swing to be the same, no matter what the amplitude of the oscillation, thus discovering the isochronal nature of the pendulum, which he verified by experiment. Galileo soon became known through his invention of a hydrostatic balance and his treatise on the center of gravity of solid bodies. While professor (1589-92) at the Univ. of Pisa, he initiated his experiments concerning the laws of bodies in motion, which brought results so contradictory to the accepted teachings of Aristotle that strong antagonism was aroused. He found that bodies do not fall with velocities proportional to their weights, but he did not arrive at the correct conclusion (that the velocity is proportional to time and independent of both weight and density) until perhaps 20 years later. The famous story in which Galileo is said to have dropped weights from the Leaning Tower of Pisa is apocryphal. The actual experiment was performed by Simon Stevin several years before Galileo's work. However, Galileo did find that the path of a projectile is a parabola, and he is credited with conclusions foreshadowing Newton's laws of motion.

Contributions to Astronomy In 1592 he began lecturing on mathematics at the Univ. of Padua, where he remained for 18 years. There, in 1609, having heard reports of a simple magnifying instrument put together by a lens-grinder in Holland, he constructed the first complete astronomical telescope. Exploring the heavens with his new aid, Galileo discovered that the moon, shining with reflected light, had an uneven, mountainous surface and that the Milky Way was made up of numerous separate stars. In 1610 he discovered the four largest satellites of Jupiter, the first satellites of a planet other than Earth to be detected. He observed and studied the oval shape of Saturn (the limitations of his telescope prevented the resolving of Saturn's rings), the phases of Venus, and the spots on the sun. His investigations confirmed his acceptance of the Copernican theory of the solar system; but he did not openly declare a doctrine so opposed to accepted beliefs until 1613, when he issued a work on sunspots. Meanwhile, in 1610, he had gone to Florence as philosopher and mathematician to Cosimo II de' Medici, grand duke of Tuscany, and as mathematician at the Univ. of Pisa.

Conflict with the Church In 1611 he visited Rome to display the telescope to the papal court. In 1616 the system of Copernicus was denounced as dangerous to faith, and Galileo, summoned to Rome, was warned not to uphold it or teach it. But in 1632 he published a work written for the nonspecialist, Dialogo … sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo [dialogue on the two chief systems of the world] (tr. 1661; rev. and ed. by Giorgio de Santillana, 1953; new tr. by Stillman Drake, 1953, rev. 1967); that work, which supported the Copernican system as opposed to the Ptolemaic, marked a turning point in scientific and philosophical thought. Again summoned to Rome, he was tried (1633) by the Inquisition and brought to the point of making an abjuration of all beliefs and writings that held the sun to be the central body and the earth a moving body revolving with the other planets about it. Since 1761, accounts of the trial have concluded with the statement that Galileo, as he arose from his knees, exclaimed sotto voce, E pur si muove [nevertheless it does move]. That statement was long considered legendary, but it was discovered written on a portrait of Galileo completed c.1640. After the Inquisition trial Galileo was sentenced to an enforced residence in Siena. He was later allowed to live in seclusion at Arcetri near Florence, and it is likely that Galileo's statement of defiance was made as he left Siena for Arcetri. In spite of infirmities and, at the last, blindness, Galileo continued the pursuit of scientific truth until his death. His last book, Dialogues Concerning Two New Sciences (tr., 3d ed. 1939, repr. 1952), which contains most of his contributions to physics, appeared in 1638. In 1979 Pope John Paul II asked that the 1633 conviction be annulled. However, since teaching the Copernican theory had been banned in 1616, it was technically possible that a new trial could find Galileo guilty; thus it was suggested that the 1616 prohibition be reversed, and this happened in 1992. The pope concluded that while 17th-century theologians based their decision on the knowledge available to them at the time, they had wronged Galileo by not recognizing the difference between a question relating to scientific investigation and one falling into the realm of doctrine of the faith.

Newton, Sir Isaac

Newton studied at Cambridge and was professor there from 1669 to 1701, succeeding his teacher Isaac Barrow as Lucasian professor of mathematics. His most important discoveries were made during the two-year period from 1664 to 1666, when the university was closed and he retired to his hometown of Woolsthorpe. At that time he discovered the law of universal gravitation, began to develop the calculus, and discovered that white light is composed of all the colors of the spectrum. These findings enabled him to make fundamental contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and theoretical and experimental physics.

The Principia Newton summarized his discoveries in terrestrial and celestial mechanics in his Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica [mathematical principles of natural philosophy] (1687), one of the greatest milestones in the history of science. In it he showed how his principle of universal gravitation provided an explanation both of falling bodies on the earth and of the motions of planets, comets, and other bodies in the heavens. The first part of the Principia is devoted to dynamics and includes Newton's three famous laws of motion; the second part to fluid motion and other topics; and the third part to the system of the world, i.e., the unification of terrestrial and celestial mechanics under the principle of gravitation and the explanation of Kepler's laws of planetary motion. Although Newton used the calculus to discover his results, he explained them in the Principia by use of older geometric methods.

Einstein, Albert

Einstein lived as a boy in Munich and Milan, continued his studies at the cantonal school at Aarau, Switzerland, and was graduated (1900) from the Federal Institute of Technology, Zürich. Later he became a Swiss citizen. He was examiner (1902-9) at the patent office, Bern. During this period he obtained his doctorate (1905) at the Univ. of Zürich, evolved the special theory of relativity, explained the photoelectric effect, and studied the motion of atoms, on which he based his explanation of Brownian movement. In 1909 his work had already attracted attention among scientists, and he was offered an adjunct professorship at the Univ. of Zürich. He resigned that position in 1910 to become full professor at the German Univ., Prague, and in 1912 he accepted the chair of theoretical physics at the Federal Institute of Technology, Zürich.

By 1913 Einstein had won international fame and was invited by the Prussian Academy of Sciences to come to Berlin as titular professor of physics and as director of theoretical physics at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. He assumed these posts in 1914 and subsequently resumed his German citizenship. For his work in theoretical physics, notably on the photoelectric effect, he received the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics. His property was confiscated (1934) by the Nazi government because he was Jewish, and he was deprived of his German citizenship. He had previously accepted (1933) a post at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, which he held until his death in 1955. An ardent pacifist, Einstein was long active in the cause of world peace; however, in 1939, at the request of a group of scientists, he wrote to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to stress the urgency of investigating the possible use of atomic energy in bombs. In 1940 he became an American citizen.

Special and General Theories of Relativity Einstein's early work on the theory of relativity (1905) dealt only with systems or observers in uniform (unaccelerated) motion with respect to one another and is referred to as the special theory of relativity; among other results, it demonstrated that two observers moving at great speed with respect to each other will disagree about measurements of length and time intervals made in each other's systems, that the speed of light is the limiting speed of all bodies having mass, and that mass and energy are equivalent. In 1911 he asserted the equivalence of gravitation and inertia, and in 1916 he completed his mathematical formulation of a general theory of relativity that included gravitation as a determiner of the curvature of a space-time continuum. He then began work on his unified field theory, which attempts to explain gravitation, electromagnetism, and subatomic phenomena in one set of laws; the successful development of such a unified theory, however, eluded Einstein.

Photons and the Quantum Theory In addition to the theory of relativity, Einstein is also known for his contributions to the development of the quantum theory. He postulated (1905) light quanta (photons), upon which he based his explanation of the photoelectric effect, and he developed the quantum theory of specific heat. Although he was one of the leading figures in the development of quantum theory, Einstein regarded it as only a temporarily useful structure. He reserved his main efforts for his unified field theory, feeling that when it was completed the quantization of energy and charge would be found to be a consequence of it. Einstein wished his theories to have that simplicity and beauty which he thought fitting for an interpretation of the universe and which he did not find in quantum theory.

Darwin, Charles Robert 1809-82, English naturalist, b. Shrewsbury; grandson of Erasmus Darwin. He firmly established the theory of organic evolution known as Darwinism. He studied medicine at Edinburgh and for the ministry at Cambridge but lost interest in both professions during the training. His interest in natural history led to his friendship with the botanist J. S. Henslow; through him came the opportunity to make a five-year cruise (1831-36) as official naturalist aboard the Beagle. This started Darwin on a career of accumulating and assimilating data that resulted in the formulation of his concept of evolution. He spent the remainder of his life carefully and methodically working over the information from his copious notes and from every other available source. Independently, A. R. Wallace had worked out a theory similar to Darwin's. Both men were exceptionally modest; they first published summaries of their ideas simultaneously in 1858. In 1859, Darwin set forth the structure of his theory and massive support for it in the superbly organized Origin of Species, supplemented and elaborated in his many later books, notably The Descent of Man (1871). Darwin also formulated a theory of the origin of coral reefs.

Darwinism,concept of evolution developed in the mid-19th cent. by Charles Robert Darwin. Darwin's meticulously documented observations led him to question the then current belief in special creation of each species. After years of studying and correlating the voluminous notes he had made as naturalist on H.M.S. Beagle, he was prompted by the submission (1858) of an almost identical theory by A. R. Wallace to present his evidence for the descent of all life from a common ancestral origin; his monumental Origin of Species was published in 1859. Darwin observed (as had Malthus) that although all organisms tend to reproduce in a geometrically increasing ratio, the numbers of a given species remain more or less constant. From this he deduced that there is a continuing struggle for existence, for survival. He pointed out the existence of variations-differences among members of the same species-and suggested that the variations that prove helpful to a plant or an animal in its struggle for existence better enable it to survive and reproduce. These favorable variations are thus transmitted to the offspring of the survivors and spread to the entire species over successive generations. This process he called the principle of natural selection (the expression "survival of the fittest was later coined by Herbert Spencer). In the same way, sexual selection (factors influencing the choice of mates among animals) also plays a part. In developing his theory that the origin and diversification of species results from gradual accumulation of individual modifications, Darwin was greatly influenced by Sir Charles Lyell's treatment of the doctrine of uniformitarianism. Darwin's evidence for evolution rested on the data of comparative anatomy, especially the study of homologous structures in different species and of rudimentary (vestigial) organs; of the recapitulation of past racial history in individual embryonic development; of geographical distribution, extensively documented by Wallace; of the immense variety in forms of plants and animals (to the degree that often one species is not distinct from another); and, to a lesser degree, of paleontology. As originally formulated, Darwinism did not distinguish between acquired characteristics, which are not transmissible by heredity, and genetic variations, which are inheritable. Modern knowledge of heredity-especially the concept of mutation, which provides an explanation of how variations may arise-has supplemented and modified the theory, but in its basic outline Darwinism is now universally accepted by scientists.

Bacon, Francis,

1561-1626, English philosopher, essayist, and statesman, b. London, educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, and at Gray's Inn. He was the son of Sir Nicholas Bacon, lord keeper to Queen Elizabeth I. Francis Bacon was a member of Parliament in 1584 and his opposition to Elizabeth's tax program retarded his political advancement; only the efforts of the earl of Essex led Elizabeth to accept him as an unofficial member of her Learned Council. At Essex's trial in 1601, Bacon, putting duty to the state above friendship, assumed an active part in the prosecution-a course for which many have condemned him. With the succession of James I, Bacon's fortunes improved. He was knighted in 1603, became attorney general in 1613, lord keeper in 1617, and lord chancellor in 1618; he was created Baron Verulam in 1618 and Viscount St. Albans in 1621. In 1621, accused of accepting bribes as lord chancellor, he pleaded guilty and was fined £40,000, banished from the court, disqualified from holding office, and sentenced to the Tower of London. The banishment, fine, and imprisonment were remitted. Nevertheless, his career as a public servant was ended. He spent the rest of his life writing in retirement. Bacon belongs to both philosophy and literature. He projected a large philosophical work, the Instauratio Magna, but completed only two parts, The Advancement of Learning (1605), later expanded in Latin as De Augmentis Scientiarum (1623), and the Novum Organum (1620). Bacon's contribution to philosophy was his application of the inductive method of modern science. He urged full investigation in all cases, avoiding theories based on insufficient data. He has been widely censured for being too mechanical, failing to carry his investigations to their logical ends, and not staying abreast of the scientific knowledge of his own day. In the 19th cent., Macaulay initiated a movement to restore Bacon's prestige as a scientist. Today his contributions are regarded with considerable respect. In The New Atlantis (1627) he describes a scientific utopia that found partial realization with the organization of the Royal Society in 1660. His Essays (1597-1625), largely aphoristic, are his best-known writings. They are noted for their style and for their striking observations about life.

Descartes, René

Descartes was educated in the Jesuit College at La Flèche and the Univ. of Poitiers, then entered the army of Prince Maurice of Nassau. In 1628 he retired to Holland, where he spent his time in scientific research and philosophic reflection. Even before going to Holland, Descartes had begun his great work, for the essay on algebra and the Compendium musicae probably antedate 1628. But it was with the appearance in 1637 of a group of essays that he first made a name for himself. These writings included the famous Discourse on Method and other essays on optics, meteors, and analytical geometry. In 1649 he was invited by Queen Christina to Sweden, but he was unable to endure the rigors of the northern climate and died not long after arriving in Sweden.

Elements of Cartesian Philosophy It was with the intention of extending mathematical method to all fields of human knowledge that Descartes developed his methodology, the cardinal aspect of his philosophy. He discards the authoritarian system of the scholastics and begins with universal doubt. But there is one thing that cannot be doubted: doubt itself. This is the kernel expressed in his famous phrase, Cogito, ergo sum [I think, therefore I am].

From the certainty of the existence of a thinking being, Descartes passed to the existence of God, for which he offered one proof based on St. Anselm's ontological proof and another based on the first cause that must have produced the idea of God in the thinker. Having thus arrived at the existence of God, he reaches the reality of the physical world through God, who would not deceive the thinking mind by perceptions that are illusions. Therefore, the external world, which we perceive, must exist. He thus falls back on the acceptance of what we perceive clearly and distinctly as being true, and he studies the material world to perceive connections. He views the physical world as mechanistic and entirely divorced from the mind, the only connection between the two being by intervention of God. This is almost complete dualism. The development of Descartes' philosophy is in Meditationes de prima philosophia (1641); his Principia philosophiae (1644) is also very important. His influence on philosophy was immense, and was widely felt in law and theology also. Frequently he has been called the father of modern philosophy, but his importance has been challenged in recent years with the demonstration of his great debt to the scholastics. He influenced the rationalists, and Baruch Spinoza also reflects Descartes's doctrines in some degree. The more direct followers of Descartes, the Cartesian philosophers, devoted themselves chiefly to the problem of the relation of body and soul, of matter and mind. From this came the doctrine of occasionalism, developed by Nicolas Malebranche and Arnold Geulincx.

Major Contributions to Science In science, Descartes discarded tradition and to an extent supported the same method as Francis Bacon, but with emphasis on rationalization and logic rather than upon experiences. In physical theory his doctrines were formulated as a compromise between his devotion to Roman Catholicism and his commitment to the scientific method, which met opposition in the church officials of the day. Mathematics was his greatest interest; building upon the work of others, he originated the Cartesian coordinates and Cartesian curves; he is often said to be the founder of analytical geometry. To algebra he contributed the treatment of negative roots and the convention of exponent notation. He made numerous advances in optics, such as his study of the reflection and refraction of light. He wrote a text on physiology, and he also worked in psychology; he contended that emotion was finally physiological at base and argued that the control of the physical expression of emotion would control the emotions themselves. His chief work on psychology is in his Traité des passions de l'âme (1649).

Philosophers

Machiavelli, Niccolò

A member of the impoverished branch of a distinguished family, he entered (1498) the political service of the Florentine republic and rose rapidly in importance. As defense secretary he substituted (1506) a citizens' militia for the mercenary system then prevailing in Italy. This reform sprang from his conviction, set forth in his major works, that the employment of mercenaries had largely contributed to the political weakness of Italy. Machiavelli became acquainted with power politics through his important diplomatic missions. He met Cesare Borgia twice and was sent by way of Florence to Louis XII of France (1504, 1510), to Pope Julius II (1506), and to Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I (1507).

The Medicis' return (1512) to Florence caused his dismissal; in 1513 he was briefly imprisoned and was tortured for his alleged complicity in a plot against the Medici. Machiavelli retired to his country estate, where he wrote his chief works. He humiliated himself before the Medici in a vain attempt to recover office. When, in 1527, the republic was briefly reestablished, Machiavelli was distrusted by many of the republicans, and he died thoroughly disappointed and embittered.

Principal Writings Machiavelli's best-known work, Il Principe [the prince] (1532), describes the means by which a prince may gain and maintain his power. His ideal prince (seemingly modeled on Cesare Borgia) is an amoral and calculating tyrant who would be able to establish a unified Italian state. The last chapter of the work pleads for the eventual liberation of Italy from foreign rule. Interpretations of The Prince vary: it has been viewed as sincere advice, as a plea for political office, as a detached analysis of Italian politics, as evidence of early Italian nationalism, and as political satire on Medici rule. However, the adjective Machiavellian has come to be a synonym for amoral cunning and for justification by power.

Less widely read but more indicative of Machiavelli's politics is his Discorsi sulla prima deca di Tito Livio [discourses on the first 10 books of Livy] (1531). In it Machiavelli expounded a general theory of politics and government that stressed the importance of an uncorrupted political culture and a vigorous political morality. Vaster in conception than The Prince, the Discourses shows clearly Machiavelli's republican principles, which are also reflected in his Istorie Fiorentine [history of Florence] (1532), a historical and literary masterpiece, entirely modern in concept.

Other works include Dell' arte della guerra [on the art of war] (1521), which viewed military problems in relation to politics, and numerous reports and brief works. He also wrote many poems and plays, notably the lively and ribald comedy Mandragola (1524). His correspondence has been preserved and is of great interest.

Spinoza, Baruch or Benedict Political Philosophy Politically, Spinoza and Hobbes again share assumptions about the social contract: Right derives from power, and the contract binds only as long as it is to one's advantage. The important difference between the two men is their understanding of the ends of the system: for Hobbes advantage lies in satisfying as many desires as possible, for Spinoza advantage lies in an escape from those desires through understanding. Put another way, Hobbes does not imagine a community of individuals whose desires can be consistently satisfied, so repression is always necessary; Spinoza can imagine such a community and such consistent satisfaction, so in his political and religious thought the notion of freedom, especially freedom of inquiry, is basic.

Hobbes, Thomas

Pronounced As: hobz , 1588-1679, English philosopher, grad. Magdalen College, Oxford, 1608. For many years a tutor in the Cavendish family, Hobbes took great interest in mathematics, physics, and the contemporary rationalism. On journeys to the Continent he established friendly relations with many learned men, including Galileo and Gassendi. In 1640, after his political writings had brought him into disfavor with the parliamentarians, he went to France (where he was tutor to the exiled Prince Charles). His work, however, aroused the antagonism of the English group in France, and his thorough materialism offended the churchmen, so that in 1651 he felt impelled to return to England, where he was able to live peacefully. Among his important works, which appeared in several revisions under different titles (see Sir W. Molesworth's edition of the complete works, 11 vol., 1839-45), are De Cive (1642), Leviathan (1651), De Corpore Politico (1650), De Homine (1658), and Behemoth (1680). In the Leviathan, Hobbes developed his political philosophy. He argued from a mechanistic view that life is simply the motions of the organism and that man is by nature a selfishly individualistic animal at constant war with all other men. In a state of nature, men are equal in their self-seeking and live out lives which are "nasty, brutish, and short. Fear of violent death is the principal motive which causes men to create a state by contracting to surrender their natural rights and to submit to the absolute authority of a sovereign. Although the power of the sovereign derived originally from the people-a challenge to the doctrine of the divine right of kings-the sovereign's power is absolute and not subject to the law. Temporal power is also always superior to ecclesiastical power. Though Hobbes favored a monarchy as the most efficient form of sovereignty, his theory could apply equally well to king or parliament. His political philosophy led to investigations by other political theorists, e.g., Locke, Spinoza, and Rousseau, who formulated their own radically different theories of the social contract.

Locke, John

Educated at Christ Church College, Oxford, he became (1660) a lecturer there in Greek, rhetoric, and philosophy. He studied medicine, and his acquaintance with scientific practice had a strong influence upon his philosophical thought and method. In 1666, Locke met Anthony Ashley Cooper, the future 1st earl of Shaftesbury, and soon became his friend, physician, and adviser. After 1667, Locke had minor diplomatic and civil posts, most of them through Shaftesbury. In 1675, after Shaftesbury had lost his offices, Locke left England for France, where he met French leaders in science and philosophy.

Returning to England in 1679, he soon retired to Oxford, where he stayed quietly until, suspected of radicalism by the government, he went to Holland and remained there several years (1683-89). In Holland he completed the famous Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690), which was published in complete form after his return to England at the accession of William and Mary to the English throne. In the same year he published his Two Treatises on Civil Government; part of this work justifies the Glorious Revolution of 1688, but much of it was written earlier. His fame increased, and he became known in England and on the Continent as the leading philosopher of freedom.

Philosophy In the Essay Concerning Human Understanding Locke examines the nature of the human mind and the process by which it knows the world. Repudiating the traditional doctrine of innate ideas, Locke believed that the mind is born blank, a tabula rasa upon which the world describes itself through the experience of the five senses. Knowledge arising from sensation is perfected by reflection, thus enabling humans to arrive at such ideas as space, time, and infinity.

Locke distinguished the primary qualities of things (e.g., solidity, extension, number) from their secondary qualities (e.g., color, sound). These latter qualities he held to be produced by the impact of the world on the sense organs. Behind this curtain of sensation the world itself is colorless and silent. Science is possible, Locke maintained, because the primary world affects the sense organs mechanically, thus producing ideas that faithfully represent reality. The clear, common-sense style of the Essay concealed many unexplored assumptions that the later empiricists George Berkeley and David Hume would contest, but the problems that Locke set forth have occupied philosophy in one way or another ever since.

Political Theory Locke is most renowned for his political theory. Contradicting Thomas Hobbes, Locke believed that the original state of nature was happy and characterized by reason and tolerance. In that state all people were equal and independent, and none had a right to harm another's life, health, liberty, or possessions. The state was formed by social contract because in the state of nature each was his own judge, and there was no protection against those who lived outside the law of nature. The state should be guided by natural law.

Rights of property are very important, because each person has a right to the product of his or her labor. Locke forecast the labor theory of value. The policy of governmental checks and balances, as delineated in the Constitution of the United States, was set down by Locke, as was the doctrine that revolution in some circumstances is not only a right but an obligation. At Shaftesbury's behest, he contributed to the Fundamental Constitutions for the Carolinas; the colony's proprietors, however, never implemented the document.

Ethical Theory Locke based his ethical theories upon belief in the natural goodness of humanity. The inevitable pursuit of happiness and pleasure, when conducted rationally, leads to cooperation, and in the long run private happiness and the general welfare coincide. Immediate pleasures must give way to a prudent regard for ultimate good, including reward in the afterlife. He argued for broad religious freedom in three separate essays on toleration but excepted atheism and Roman Catholicism, which he felt should be legislated against as inimical to religion and the state. In his essay The Reasonableness of Christianity (1695), he emphasized the ethical aspect of Christianity against dogma.

Rousseau, Jean Jacques

Rousseau was born at Geneva, the son of a watchmaker. His mother died shortly after his birth, and his upbringing was haphazard. At 16 he set out on a wandering, irregular life that brought him into contact (c.1628) with Louise de Warens, who became his patron and later his lover. She arranged for his trip to Turin, where he became an unenthusiastic Roman Catholic convert. After serving as a footman in a powerful family, he left Turin and spent most of the next dozen years at Chambéry, Savoy, with his patron. In 1742 he went to Paris to make his fortune with a new system of musical notation, but the venture failed. Once in Paris, however, he became an intimate of the circle of Denis Diderot (to whose Encyclopédie Rousseau contributed music articles), Melchior Grimm, and Mme d'Épinay. At this time also began his liaison with Thérèse Le Vasseur, a semiliterate servant who became his common-law wife.

In 1749, Rousseau won first prize in a contest, held by the Academy of Dijon, on the question: Has the progress of the sciences and arts contributed to the corruption or to the improvement of human conduct? Rousseau took the negative stand, contending that humanity was good by nature and had been fully corrupted by civilization. His essay made him both famous and controversial. Although it is still widely believed that all of Rousseau's philosophy was based on his call for a return to nature, this view is an oversimplification, caused by the excessive importance attached to this first essay. A second philosophical essay, Discours sur l'origine de l'inégalité des hommes (1754), is one of Rousseau's most mature and daring productions. After its publication, Rousseau returned to Geneva, reverted to Protestantism in order to regain his citizenship, and returned to Paris with the title citizen of Geneva.

Mme d'Épinay lent him a cottage, the Hermitage, on her estate at Montmorency. But Rousseau began to quarrel with Mme d'Épinay, Diderot, and Grimm, all of whom he accused of complicity in a sordid plot against him, and left the Hermitage to become the guest of the tolerant duc de Luxembourg, whose château was also at Montmorency. There he finished his novel, Julie, ou La Nouvelle Héloïse (1761), written in part under the influence of his love for Mme d'Houdetot, the sister-in-law of Mme d'Épinay; his Lettre à d'Alembert sur les spectacles (1758), a diatribe against the suggestion that Geneva would be better off for having a theater; his Du contrat social (1762); and his Émile (1762), which offended both the French and Genevan ecclesiastic authorities and was burned at Paris and at Geneva.

Rousseau, with the connivance of highly placed friends, escaped, however, to the Swiss canton of Neuchâtel, then a Prussian possession. His house was stoned, and Rousseau fled once more, this time to the canton of Bern, settling on the small island of Saint-Pierre, in the Lake of Biel. In 1765 he was expelled from Bern and accepted the invitation of David Hume to live at his house in England; there he began to write the first part of his Confessions, but after a year he quarreled violently with Hume, whom he believed to be in league with Diderot and Grimm, and returned to France (1767). His suspicion of people deepened and became a persecution mania.

After wandering through the provinces, he finally settled (1770) at Paris, where he lived in a garret and copied music. The French authorities left him undisturbed, while curious foreigners flocked to see the famous man and be insulted by him. At the same time he went from salon to salon, reading his Confessions aloud. In his last years he began Rêveries du promeneur solitaire, descriptions of nature and his feeling about it, which was unfinished at the time of his death. Shortly before his death Rousseau moved to the house of a protector at Ermenonville, near Paris, where he died. In 1794 his remains were transferred to the Panthéon in Paris.

Rousseau's Thought Few people have equaled Rousseau's influence in politics, literature, and education. His political thought is contained in Du contrat social, but it must be supplemented by other works, notably the Discours sur l'origine de l'inégalité and his drafts of constitutions for Corsica and for Poland. Rousseau is fundamentally a moralist rather than a metaphysician. As a moralist, he is also, unavoidably, a political theorist. His thought begins with the assumption that we are by nature good, and with the observation that in society we are not good. The fall of humanity was, for Rousseau, a social occurrence. But human nature does not go backward, and we never return to the times of innocence and equality, when we have once departed from them.

Although he locates the cause of our deformity in society, Rousseau is not a primitivist. In Émile and Du contrat social, he proposed, on an individual and a social level, what might be done. What was new and important about his educational philosophy, as outlined in Émile, was its rejection of the traditional ideal: education was not seen to be the imparting of all things to be known to the uncouth child; rather it was seen as the drawing out of what is already there, the fostering of what is native. Rousseau's educational proposal is highly artificial, the process is carefully timed and controlled, but with the end of allowing the free development of human potential.

Similarly, with regard to the social order, Rousseau's aim is freedom, which again does not involve a retreat to primitivism but perfect submission of the individual to what he termed the general will. The general will is what rational people would choose for the common good. Freedom, then, is obedience to a self-imposed law of reason, self-imposed because imposed by the natural laws of humanity's being. The purpose of civil law and government, of whatever form, is to bring about a coincidence of the general will and the wishes of the people. Society gives government its sovereignty when it forms the social contract to achieve liberty and well- being as a group. While this sovereignty may be delegated in various ways (as in a monarchy, a republic, or a democracy) it cannot be transferred and resides ultimately with society as a whole, with the people, who can withdraw it when necessary.

Rousseau's political philosophy assumes that there really is a common good, and that the general will is not merely an ideal, but can, under the right conditions, be actual. And it is under such conditions, with the rule of the general will, that Rousseau sees our full development taking place, when the advantages of a state of nature would be combined with the advantages of social life. Because he had such faith in the existence of the common good and the rightness of the general will, Rousseau was extreme in the sanctions he was willing to allow for its achievement: If anyone, after publicly recognizing these dogmas, behaves as if he does not believe them, let him be punished by death: He has committed the worst of all crimes, that of lying before the law. Finally, Rousseau advocates a civil religion. Rousseau's thought sometimes rings of Calvinist Geneva, even though he reacted against its vision of humanity and had his books burned by its ecclesiastic authorities.

In its time his epistolary novel Héloïse was immensely popular, but it is scarcely read today, while the Confessions remains widely read. Proposing to describe not only his life, but also his innermost thought and feelings, hiding nothing be it ever so shameful, Rousseau followed the model of St. Augustine's Confession, but he created a new, intensely personal style of autobiography. The Héloïse, Émile, the Confessions, and the Rêveries all transfer to the domain of literature Rousseau's longing for a closeness with nature.

His sensitive awareness apprehended the subtle influences of landscape, trees, water, birds, and other aspects of nature on the shifting state of the human soul. Rousseau was the father of Romantic sensibility; the trend existed before him, but he was the first to give it full expression. Rousseau's style, in all his writings, is always personal, sometimes bizarre, sometimes rhetorical, sometimes bitterly sarcastic, sometimes deliberately plebeian, and often animated by a tender and musical quality unequaled in French prose. Although self-taught, he possessed a thorough knowledge of musical theory, but his compositions exerted no direct influence on music.

Influence Rousseau's influence on posterity has been equaled by only a few, and it is by no means spent. His influence on German and English romanticism-and thus, indirectly, on romanticism in general-is difficult to overestimate. In addition, men as diverse as Immanuel Kant, Johann Goethe, Maximilien de Robespierre, Johann Pestalozzi, and Leo Tolstoy have been his disciples. His doctrine of popular sovereignty had a profound impact on French revolutionary thought. Although he did not advocate collective ownership, his ideas also had their effect on socialist thought. It is probably more correct to say that he anticipated rather than influenced many insights of modern social psychology.

Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm

Pronounced As: frdrikh vilhelm nch , 1844-1900, German philosopher, b. Röcken, Prussia. The son of a clergyman, Nietzsche studied Greek and Latin at Bonn and Leipzig and was appointed to the chair of classical philology at Basel in 1869. In his early years he was friendly with the composer Richard Wagner, although later he was to turn against him. Nervous disturbances and eye trouble forced Nietzsche to leave Basel in 1879; he moved from place to place in a vain effort to improve his health until 1889, when he became hopelessly insane. Nietzsche was not a systematic philosopher but rather a moralist who passionately rejected Western bourgeois civilization. He regarded Christian civilization as decadent, and in place of its "slave morality he looked to the superman, the creator of a new heroic morality that would consciously affirm life and the life values. That superman would represent the highest passion and creativity and would live at a level of experience beyond the conventional standards of good and evil. His creative "will to power would set him off from "the herd of inferior humanity. Nietzsche's thought had widespread influence but was of particular importance in Germany. Apologists for Nazism seized on much of his writing as a philosophical justification for their doctrines, but most scholars regard this as a perversion of Nietzsche's thought. Among his most famous works are The Birth of Tragedy (1872, tr. 1910); Thus Spake Zarathustra (1883-91, tr. 1909, 1930), and Beyond Good and Evil (1886, tr. 1907).

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich

Educated in theology at Tübingen, Hegel was a private tutor at Bern and Frankfurt. In 1801 he became privatdocent [tutor] and in 1805 professor at the Univ. of Jena. While considered a follower of Schelling, he was developing his own system, which he first presented in Phenomenology of Mind (1807). During the Napoleonic occupation Hegel edited (1807-8) a newspaper, which he left to become rector (1808-16) of a Gymnasium at Nuremberg. He then returned to professorships at Heidelberg (1816-18) and Berlin (1818-31), where he became famous.

In his lectures at Berlin he set forth the system elaborated in his books. Chief among these were Science of Logic (1812-16); Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences (1817), an outline of his whole philosophy; and Philosophy of Right (1821). He also wrote books on ethics, aesthetics, history, and religion. His interests were wide, and all were incorporated into his unified philosophy.

The Hegelian Dialectic Hegel's absolute idealism envisaged a world-soul that develops out of, and is known through, the dialectical logic. In this development, known as the Hegelian dialectic, one concept (thesis) inevitably generates its opposite (antithesis), and the interaction of these leads to a new concept (synthesis). This in turn becomes the thesis of a new triad. Hegel regarded Kant's study of categories as incomplete. The idea of being is fundamental, but it evokes its antithesis, not being. However, these two are not mutually exclusive, for they necessarily produce the synthesis, becoming. Hence activity is basic, progress is rational, and logic is the basis of the world process.

Nature and the State The study of nature and mind reveal reason as it realizes itself in cosmology and history. The world process is the absolute, the active principle that does not transcend reality but exists through and in it. The universe develops by a self- creating plan, proceeding from astral bodies to the world, from the mineral kingdom to the vegetable, from the vegetable kingdom to the animal. In society the same progress can be discovered; human activities lead to property, which leads to law.

Out of the relationship between the individual and law develops the synthesis of ethics, where both the interdependence and the freedom of individuals interact to produce the state. The state thus is a totality above all individuals, and since it is a unit, its highest development is rule by monarchy. Such a state is an embodiment of the absolute idea. In his study of history, Hegel reviewed the history of states that held sway over lesser peoples until a higher representative of the absolute evolved. Though much of his development was questionable, the concept of the conflict of cultures stimulated historical analysis. Aesthetics and Religion Hegel considered art a closer approach to the absolute than government. In the history of art he distinguished three periods-the Oriental, the Greek, and the romantic. He believed that the modern romantic form of art cannot encompass the magnitude of the Christian ideal. Hegel taught that religion moved from worship of nature through a series of stages to Christianity, where Christ represents the union of God and humanity, of spirit and matter. Philosophy goes beyond religion as it enables humankind to comprehend the entire historical unfolding of the absolute.

Influence Hegel has influenced many subsequent philosophies-post-Hegelian idealism, the existentialism of Kierkegaard and Sartre, the socialism of Marx and Lasalle, and the instrumentalism of Dewey. His theory of the state was the guiding force of the group known as the Young Hegelians, who sought the unification of Germany. His lectures on philosophy, religion, aesthetics, and history were collected in eight volumes after his death.

Kant, Immanuel

Kant was educated in his native city, tutored in several families, and after 1755 lectured at the Univ. of Königsberg in philosophy and various sciences. He became professor of logic and metaphysics in 1770 and achieved wide renown through his writings and teachings. His early work, reflecting his studies of Christian Wolff and G. W. Leibniz, was followed by a period of great development culminating in the Kritik der reinen Vernunft (1781, tr. Critique of Pure Reason). This work inaugurated his so-called critical period- the period of his major writings. The more important among these writings were Prolegomena zu einer jeden künftigen Metaphysik (1783, tr. Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics), Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten (1785, tr. Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals), Kritik der praktischen Vernunft (1788, tr. Critique of Practical Reason), and Kritik der Urteilskraft (1790, tr. Critique of Judgment). His Religion innerhalb der Grenzen der blossen Vernunft (1793, tr. Religion within the Limits of Reason Alone) provoked a government order to desist from further publications on religion.

Philosophy According to Kant, his reading of David Hume awakened him from his dogmatic slumber and set him on the road to becoming the critical philosopher, whose position can be seen as a synthesis of the Leibniz-Wolffian rationalism and the Humean skepticism. Kant termed his basic insight into the nature of knowledge the Copernican revolution in philosophy.

Instead of assuming that our ideas, to be true, must conform to an external reality independent of our knowing, Kant proposed that objective reality is known only insofar as it conforms to the essential structure of the knowing mind. He maintained that objects of experience-phenomena-may be known, but that things lying beyond the realm of possible experience-noumena, or things-in- themselves-are unknowable, although their existence is a necessary presupposition. Phenomena that can be perceived in the pure forms of sensibility, space, and time must, if they are to be understood, possess the characteristics that constitute our categories of understanding. Those categories, which include causality and substance, are the source of the structure of phenomenal experience.

The scientist, therefore, may be sure only that the natural events observed are knowable in terms of the categories. Our field of knowledge, thus emancipated from Humean skepticism, is nevertheless limited to the world of phenomena. All theoretical attempts to know things-in-themselves are bound to fail. This inevitable failure is the theme of the portion of the Critique of Pure Reason entitled the Transcendental Dialectic. Here Kant shows that the three great problems of metaphysics-God, freedom, and immortality- are insoluble by speculative thought. Their existence can be neither affirmed nor denied on theoretical grounds, nor can they be scientifically demonstrated, but Kant shows the necessity of a belief in their existence in his moral philosophy.

Kant's ethics centers in his categorical imperative (or moral law)-Act as if the maxim from which you act were to become through your will a universal law. This law has its source in the autonomy of a rational being, and it is the formula for an absolutely good will. However, since we are all members of two worlds, the sensible and the intelligible, we do not infallibly act in accordance with this law but, on the contrary, almost always act according to inclination. Thus what is objectively necessary, i.e., to will in conformity to the law, is subjectively contingent; and for this reason the moral law confronts us as an ought.

In the Critique of Practical Reason Kant went on to state that morality requires the belief in the existence of God, freedom, and immortality, because without their existence there can be no morality. In the Critique of Judgment Kant applied his critical method to aesthetic and teleological judgments. The chief purpose of this work was to find a bridge between the sensible and the intelligible worlds, which are sharply distinguished in his theoretical and practical philosophy. This bridge is found in the concepts of beauty and purposiveness that suggest at least the possibility of an ultimate union of the two realms.

Freud, Sigmund froid, 1856-1939, Austrian psychiatrist, founder of psychoanalysis. Born in Moravia, he lived most of his life in Vienna, receiving his medical degree from the Univ. of Vienna in 1881.

His medical career began with an apprenticeship (1885-86) under J. M. Charcot in Paris, and soon after his return to Vienna he began his famous collaboration with Josef Breuer on the use of hypnosis in the treatment of hysteria. Their paper, On the Psychical Mechanism of Hysterical Phenomena (1893, tr. 1909), more fully developed in Studien über Hysterie (1895), marked the beginnings of psychoanalysis in the discovery that the symptoms of hysterical patients-directly traceable to psychic trauma in earlier life- represent undischarged emotional energy (conversion; see hysteria). The therapy, called the cathartic method, consisted of having the patient recall and reproduce the forgotten scenes while under hypnosis. The work was poorly received by the medical profession, and the two men soon separated over Freud's growing conviction that the undefined energy causing conversion was sexual in nature.

Freud then rejected hypnosis and devised a technique called free association (see association), which would allow emotionally charged material that the individual had repressed in the unconscious to emerge to conscious recognition. Further works, The Interpretation of Dreams (1900, tr.1913), The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1904, tr.1914), and Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905, tr. 1910), increased the bitter antagonism toward Freud, and he worked alone until 1906, when he was joined by the Swiss psychiatrists Eugen Bleuler and C. G. Jung, the Austrian Alfred Adler, and others.

In 1908, Bleuler, Freud, and Jung founded the journal Jahrbuch für psychoanalytische und psychopathologische Forschungen, and in 1909 the movement first received public recognition when Freud and Jung were invited to give a series of lectures at Clark Univ. in Worcester, Mass. In 1910 the International Psychoanalytical Association was formed with Jung as president, but the harmony of the movement was short-lived: between 1911 and 1913 both Jung and Adler resigned, forming their own schools in protest against Freud's emphasis on infantile sexuality and the Oedipus complex. Although these men, and others who broke away later, objected to Freudian theories, the basic structure of psychoanalysis as the study of unconscious mental processes is still Freudian. Disagreement lies largely in the degree of emphasis placed on concepts largely originated by Freud.

He considered his last contribution to psychoanalytic theory to be The Ego and the Id (1923, tr. 1927), after which he reverted to earlier cultural preoccupations. Totem and Taboo (1913, tr. 1918), an investigation of the origins of religion and morality, and Moses and Monotheism (1939, tr. 1939) are the result of his application of psychoanalytic theory to cultural problems. With the National Socialist occupation of Austria, Freud fled (1938) to England, where he died the following year.

Freudian theory has had wide impact, influencing fields as diverse as anthropology, education, art, and literary criticism. His daughter, Anna Freud, was a major proponent of psychoanalysis, developing in particular the Freudian concept of the defense mechanism. Other works include A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis (1910, tr. 1920) and New Introductory Lectures on Psycho-analysis (1933).

Religious Leaders

Luther, Martin

Luther was educated at the cathedral school at Eisenach and at the Univ. of Erfurt (1501-5). In 1505 he completed his master's examination and began the study of law. Several months later, after what seems to have been a sudden religious experience, he entered a monastery of the Augustinian friars at Erfurt. There, devoutly attentive to the rigid discipline of the order, he began an intensive study of Scripture and was ordained a priest in 1507. In 1508 he was sent to the Univ. of Wittenberg to study and to lecture on Aristotle. In 1510, Luther was sent to Rome on business for his order, and there he was shocked by the spiritual laxity apparent in high ecclesiastical places.