Pohl 1

Analysis of Cedar Fire Information and Evacuation Failure

Jason R. Pohl

Colorado State University

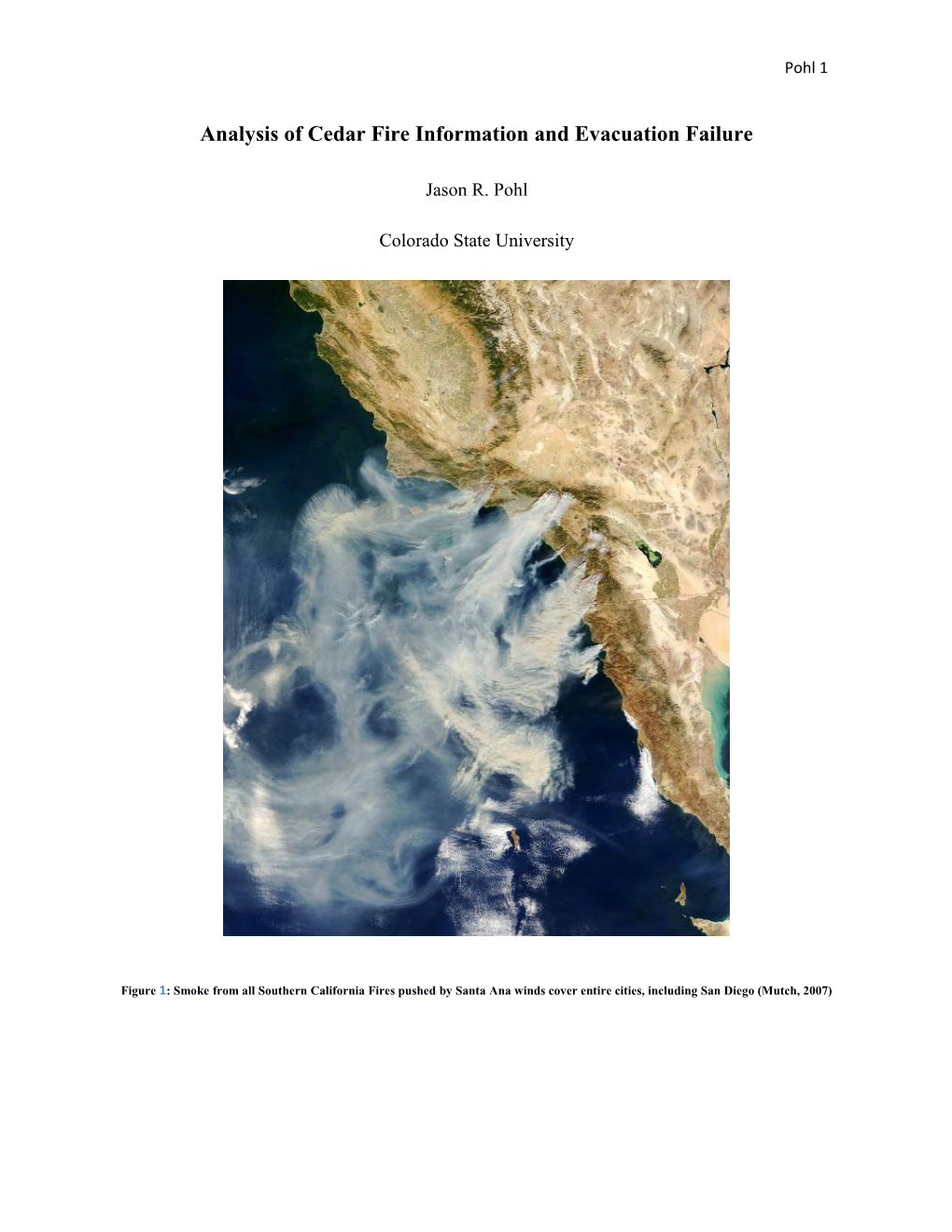

Figure 1: Smoke from all Southern California Fires pushed by Santa Ana winds cover entire cities, including San Diego (Mutch, 2007) Pohl 2

Abstract

Purpose –This article will explore the 2003 Cedar Fire in San Diego County, which became the largest fire in California history, and it will show that there were major problems in the evacuation of citizens, especially in rural areas. These problems can be rooted in two areas: information breakdown and the lack of resources for livestock owners/those with special circumstances.

Design/Approach – A review of several comprehensive post-event documents that illustrate what happened on both a macroscopic level as well as a personal level was used.

Additional statistics from various agencies will further our understanding of how powerful this event became. Additional first-hand recollections from newspaper reports and interviews will be used to truly comprehend what disadvantaged populations endured, all to demonstrate that changes need to occur.

Findings – The agencies in charge of managing these disasters were unprepared for such a rapidly spreading fire in almost all regards, and the windy conditions, extended drought, and rural origin of the fire made it difficult to combat. Residents in upscale neighbors were unprepared for wildfires to enter city limits, and those in rural areas were unprepared for the magnitude of this event, complicating evacuation protocol.

Limitations – Quality data from multiple sources make this a well-researched article.

Originality – I experienced this event from a rural environment and provide a personal portrayal of what happened. Many heard about the multi-million dollar homes destroyed in the city, but few learned of the destruction on the rural communities. Pohl 3

Introduction

The 2003 Cedar fire scorched over 270,000 acres, destroyed nearly 5,000 structures including 2,232 homes, and ultimately cost over 2 billion dollars (Mutch, 2007). 14 lives were lost, and the impact of this fire storm can be seen in all aspects of life even today in San Diego

County. I grew up in the San Diego backcountry in one of the small towns that pepper the remote, ranch-filled, normally peaceful mountains. When the evacuation orders finally came days into the already massive inferno, I experienced what true chaos looked like in all forms for all people. I saw many who stayed behind, unaware of how bad this would truly become, and I saw many who freed their animals in hopes that they would find safety somewhere. I witnessed clogged roads, packed parking lots, and utter desperation for resources including information about what was happening at people’s empty homes.

While I was fortunate and did not lose my home, property, or a loved one, thousands of others did lose something. Many had to rebuild their entire lives from the ground up. For the lives of those who lived in the rural areas of the county, the evacuation process and the entire event was much more difficult. Due to communication failures from evacuation leaders, disaster managers, and the media, many in both rural and urban areas were left guessing what to do.

Further, those in rural areas often were void of resources for themselves and their animals to safely flee their homes. There is no reason either of these situations should have been present, even though the magnitude of this event was so unprecedented.

Information Breakdown Pohl 4

The Cedar Fire was unlike anything the county of San Diego or the State of California had ever seen. The fire ripped through the brittle chaparral and marched towards the city, covering over 28 miles in just 14 hours, mostly during the night when many people slept (Mutch,

2007). Winds reached upwards of 50 miles per hour, and pushed the flames from the chaparral areas of the mountain to the urban, densely populated San Diego city limits. Fires are common in the rural areas of the county, and many who resided in the populated areas were not expecting to be impacted by this event because they rarely were in the past.

Many were awoken suddenly to the sounds of Sherriff’s horns, warning of the imminent threat. They were forced to make “a crazed dash for their lives” (Mutch, 2007), and many were overcome by the massive flames in their cars. Several, including Diane McLean near the Barona

Indian Reservation, awoke to the smell of smoke, saw the flames, and quickly called relatives, who also called friends, until entire neighborhoods were warned. There were no formal warnings by officials. Instead, communities acted together to warn each other, though many lost their lives in this beginning stage of the week long ordeal (Mutch, 2007). Pohl 5

Figure 2: The enormous fire's rapid spread through the county. (Bowman, 2004 and Mutch, 2007)

Even if many were able to flee the horrific scenario that was unfolding, there was still the issue of where to go. People were not told anything about the situation and just tried to get away. This chaotic scene was not just in one area, but, as seen in the diagram, occurred on an enormous scale.

Those in the rural areas of the inferno fared no better. Though population density is significantly decreased, the number of escape routes was also minimal. For those that needed to flee quickly, there was widespread confusion about what roads were accessible, burned over, and dead ends. Figure 2 depicts fire cover combined with major roadways, and it is clear that the evacuation process for this event would have to be much different than previous conflagrations. Pohl 6

As day broke and the reality became real and images of the smoke, flames, and destruction flooded newsrooms such as that of ABC 10, and residents realized what was occurring. However, as was my case and thousands others, electricity went out soon after. With information limited to personal interactions, chaos quickly devoured the backcountry.

“Everyone was relying on what people saw when they went for a drive down the road or hiked to the top of a nearby mountain to see what was really going on” (Greene, 2010). Some were able to listen to radio broadcasts, but, as was traditionally the case, those in unincorporated communities were often ignored, and even though the fire continued to spread, nobody really knew when and where the fire would go. “The smoke had been visible from the beginning, and then the wind shifted. Smoke made breathing difficult, and the Sherriff told everyone to get out”

(Greene 2010). Again, confusion as to what evacuation shelter to go to, where the fire was and how to get out quickly filled the communities and bogged down the traffic on roadways, as seen in Figure 3 below.

In disaster events, it is common for civilian populations to act with a herd mentality.

Further, it is reasonable to believe some knowledge of what is happening will be lost or altered Pohl 7 with person to person communication. However, traditionally, agencies in charge including the

Forest Service, Fire Departments, and the Federal Government act together to control a population in a safe and orderly fashion. Many factors contributed to the breakdown and eventual failure of this system, including the vast areas and jurisdictions covered lack of manpower and resources, civilian reentry policy, lack of funding, untrained/inexperienced commanders, and the sheer severity of this event (Bowman, 2004). Simply put, hindsight investigations show how this disaster overwhelmed not just those civilians being run from their homes but also those in charge of keeping the public informed and safe.

Figure 3: Fire Advances to Densely Populated Residential Community in Poway (Mutch, 2007)

Even though the most severe wildfire in California history did so much damage to both land, property, and lives, it “provide[d] a valuable learning experience, which cannot be replicated in the classroom” (Bowman, 2004). Many changes to policy regarding information flow have been made to better warn those in the path of the oncoming disaster. As seen in the

San Diego fires of 2009, reverse 911 calls were made to neighborhoods to warn of imminent doom, giving everyone accurate information about where to go, when to leave, and what to do. Pohl 8

This was proven effective in the Witch Fires of 2007, which were enormous in size, but minimal in lives lost (Pendray, 2007).

Additional information measures have also been made, including more detailed media broadcasts and mapping regarding how wildfires are spreading. Further, media coverage saturates the networks as events unfold, seeking to better inform not only those in the upper class areas but also anyone near the area. Emergency Management Offices have completely redrawn the maps of evacuation to fit multiple complicated scenarios and provided this information towards local governments who then notify the communities (Bowman, 2004).

Though it is encouraging to believe that changes made in wake of the Cedar Fire have eliminated chaos in evacuations and communications, it simply is not true. “Nobody told us to leave. My friend called and said there was fire near her house, so my family packed up, waited, and finally left. We drove down Highway 94 [the only way out] and had to drive through smoke and flames before we finally got somewhere safe” (Nunez, 2010). This was not for the Cedar

Fire, but actually for the Harris Fire, which happened 4 years and numerous policy changes later.

“We were lucky to get out when we did. Otherwise the smoke would have cut the engine of our car and we would have be burned right there on the road” (Nunez, 2010). If these horrific evacuation stories continue to form every time there is a fire, clearly, there is more to be done before we can say that communication processes are working.

What about those with special circumstances?

Ultimately, citizens have learned to be better prepared for these events, but sometimes there is more to being prepared then just having food, water, and a way out. Many families do not consist simply of a mother, father, and 2 children, but instead are more complex.

Additionally, rural areas of San Diego are known for their easy going, ranch style communities Pohl 9 on which may reside numerous heads of cattle, pigs, goats, sheep, and horses. These unique parts of the community were often forgotten as the event developed.

For instance, when a fire suddenly erupts and threatens the land of a cattle rancher, owners of these animals cannot simply take them all to safety. During the Cedar Fire, many people stayed to defend their animals, property, and historic homes, even if the task was too large for them to do, and this complicated the firefighting efforts, rescue efforts, and added to the massive confusion already present. Those with fewer animals and primarily horses often migrated to shopping-center parking lots where make-shift stables had been constructed. There was little relief both medically and mentally for these horses, and pandemonium quickly followed (Pendray, 2007).

There are procedures and actions being taken to help these animal lovers evacuate safely with the assurance that their pet will be. Organizations have been formed that help in evacuating the effected animals safely, free of charge for the owner, until the owner can take control again.

Also, a network of those who can accommodate large animals has been formed, specifically in rural areas, and in the event of an evacuation, people can quickly find a place for their pets.

Additional medical support is now almost always present on these make-shift horse communities. Trained animal owners and breeders can volunteer their time to assist with the stress the animals are facing, greatly reducing the amount of suffering the animals face (Pendray,

2007).

If people have the option of moving their animals somewhere safe quickly and easily, rather than letting them go to fend for themselves, not only animal lives be saved, but human lives will be able to evacuate, easing the firefighting efforts and reducing the amount of destruction. Pohl 10

An additional group that is often overlooked in the post-disaster evaluation is the elderly.

In any fire event, as previously discussed, communication is essential in minimizing the loss of life. Over recent decades, the United States has seen a drastic rise in elderly individuals living alone. These increases in solitary living further complicate evacuation processes in all disasters.

Many elderly individuals simply do not have the access to information beyond what people tell them and what they see on television, and this can be detrimental to the evacuation process.

(Klinenber, 2003). As seen during the Cedar Fire, many in rural areas felt they had seen fires before and felt they could tough it out, even when the electricity failed, cutting off their primary source of information: the television. (Mutch, 2007)

Instead of packing like many others, these isolated people often stayed at home until a relative or emergency official came to their rescue, and this complicated the entire scheme of the evacuation process. Resources were tied up trying to save these people who could not leave by themselves (Mutch, 2007).

Another aspect is how much an elderly person can do physically, and as seen during the

2003 fires, several deaths were caused by heart attacks as people attempted to flee the oncoming disaster. There were at least 6 reported deaths caused by heart attacks among those 65 years of age and above. It has been determined that all of these people were trying to load their vehicles and escape, and the stress of the situation actually caused their heart failure (Mutch, 2007). There is no reason for this. All it would have taken is for a younger person to help the elderly load their car, but instead a life was lost.

As a result, many updated networks linking the elderly to more youthful neighbors have been formed. With these increased social ties and an increased sense of community, those who may be frail and confused when similar disasters are occurring will have people to help them Pohl 11 quickly. I witnessed first-hand the community partnerships that formed after this event, and neighbors actually warning and helping others before evacuating. This is the most promising method outreach towards society’s aged population, and if they are able to receive adequate information and assistance, the entire process will run much smoother.

Conclusion

Wildfires are becoming more prevalent in the lives Southern California residents, but the

2003 Cedar Fire that ravaged a majority of San Diego County was different. Because it spread so incredibly fast and caught everyone off-guard, it demonstrated just how quickly standard operating procedures can fail. This failure, while costly, did provide a spectacular learning experience for those in evacuation and prevention, Emergency Responders, and everyday citizens (Bowman, 2004). This system failure can be attributed to a variety of things, ranging from weather patterns at the time to procedural dilemmas facing managers, and much has been done to remedy the problems involving communication and information transfer for the future events.

Further, a lot has been said about the evacuation process as a whole, but little has been done to explain the situations the elderly and those with outlying circumstances based on animals face in firestorms such as the one in 2003. These groups often have a lack of information and resource during the disaster, and do not have the means to act in the necessary manner.

A lot has been learned from largest wildfire in California history. Rebuilding continues to this day, and procedures are still being instituted as populations increase and the risk of a future fire increases. Clearly, there is still more to be done if organizers plan to prevent similar events from ravishing the landscape and decimating the communities and lives of thousands. Pohl 12

Figure 4: One of the many neighborhoods that were decimated due to the Cedar Fire. (Bowman, 2004) Reference List

Bowman, J. (2004) Cedar Fire 2003 After Action Report. City of San Diego Fire Rescue Department. Final Report.

Nunez, E. Interviewed by Pohl, J. (23 March, 2010) 9pm.

Greene, M. Interviewed by Pohl, J. (20 March, 2010) 4pm.

Klineber, E. (2003). A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago. University of Chicago Press.

Mutch, R. (2007) FACES: The Story of the Victims of Southern California’s 2003 Fire Siege. Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center.

Pendray, J. (2009) “San Diego Braces for Santa Ana Fires; Communications, Evacuation plans tweaked,” The Washington Times. 5 September, 2009. p 1.