Lake Texcoco's Memory Tale

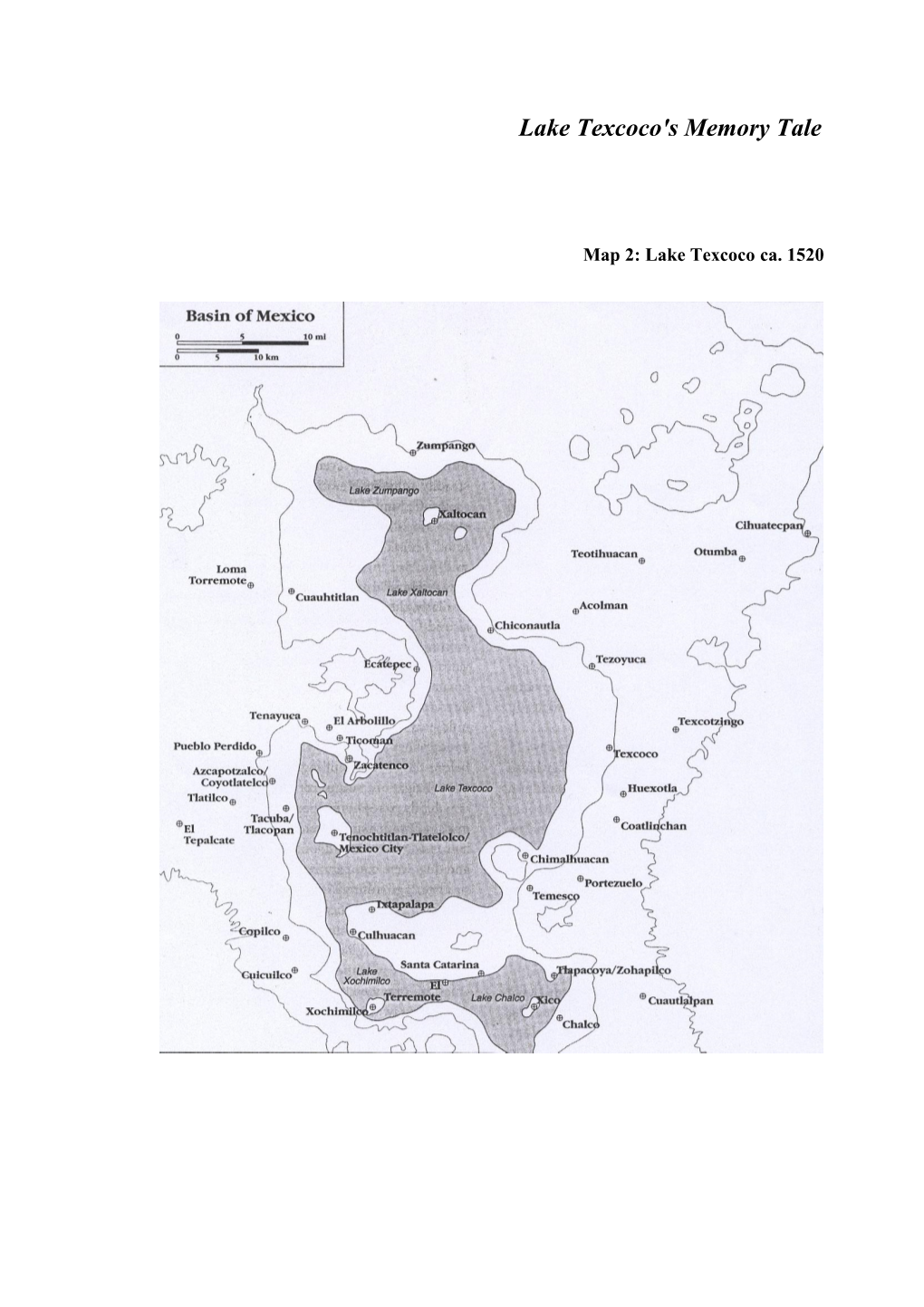

Map 2: Lake Texcoco ca. 1520 In 1520, the entire cultural schemata, upon which remembrance was based in this distinct area of

Lake Texcoco, were embedded in the cartographic histories and cadastral maps of each town and district and was heavily reinforced by oral recalling. Around Lake Texcoco, the seat of the great

Triple Alliance rulers, people referred to what they recalled of what were the most dominant emblems, cultural forms, and patterns in Chichimeca heritage, inscribed upon the lienzos. What one is able to identify here “cultural grammars, which are analogous to the grammars of linguistics” -- is firmly embedded their environmental existence and cultural experience and, obviously, in direct relationships with the Lake (huey atezcatl): the aquatic foodstuffs; the reeds/rushes (tollin); mats, which are also depicted in expressions such as, aiopaniehuatl (“That which is on the damp side”), tolnahuac (“near the tules”) or, atlan (“next to the water”). The canoes (acalli); the muddy earth; the

.canals (teapiaztli); the bridges (quappantli), the salt works, and the drains

The mid-sixteenth century map of Alonso de Santa Cruz shows Cuitlahuac as an island situated between Lake Xochimilco and Lake Chalco in a marsh, which is traversed by canals and causeways.

Its peoples were named as chinampatlaca (“floating island dwellers”). ahuxotl [ Salix bonplandiana= willow tree] was planted around the chinampa [floating gardens] in Xochimilco, Chalco and

Texcoco, as natural limits; tollin was used there for diverse purposes as well as in commerce, was regarded as an integral part of the town’s cherished heritage [pialoni], and served also for the purpose of dividing the Lake among its various owners [atlixeliahian= “where the water is divided”].1 Fresh rushes were used as matting to cover the ground during ceremonies,2 in the same manner as pine needles that were spread on the ground in the post-conquest native churches. One also finds in native pictograms the glyph of tolpetlac, meaning, “en el petate del tule” (On the Reed Mat). The visual recalling of all these components, translated and imparted through the process of memorability, and

.utilized as mnemonics, often appears throughout the various Lake Texcoco’s lawsuits, below Furthermore, the essence of these towns’ collective memory of their common heritage concerned the alliances established, their common fate, the lands divided among them, the boundaries set and the rulers who had dominated the area prior to the Spaniards. Around Lake Texcoco, during the first two decades after the conquest, Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco divided among them an island occupying about four square miles in Lake Texcoco. Each share contained subdivisions of different sizes with subordinate calpolli scattered about on the shores of the Lake, and on the surrounding hills.3 Notions of political and religious acknowledgment of subordination and superiority, were enacted and re- enacted in commemorative performances for at least for the next one hundred years following the

Tlatelolco subjugation by Tenochtitlan (in 1473). Around 1523, commemoration among all those towns was prominently based upon what was to be found in, perhaps, one of the most significant canonical records of boundary-making decorum of the pre-Columbian era that survived after the

Spanish conquest. The cartographic history of the Lake was utilized by the last Aztec Emperor,

Cuauhtemoc, to make public in 1523 the royal decree over the division of the lake. The pictorial antecedents of this manuscript were still in the possession of the Mexica royal court, at the time of the conquest, and related the division of the lake among the various barrios [tlaxilacalme] of

4.Tlatelolco and Tenochtitlan

The 1528 Manuscript

The manuscript, which is entitled Cédula dada por el emperador Quauhtemotzin para el reparto de la laguna grande de Tescuco is composed of three cartographic “maps”, or histories [annals], executed under the impact of more ancient “maps”, originating from as early as 1361. They were originally painted on maguey paper, and then copied on European paper; they were 31 cm high and

43 cm long. Numerous notes in Nahuatl appeared on the three copies in the manner of topographical plans with measurements, as well as the names of Aztec princes and other personalities who had inherited some of these lands on the shores of the lake. Adjoining was the Spanish translation of

1704, by Manuel Mancio, an interpreter at the court of the Audiencia of Mexico; the translation was placed within the framework of evidence submitted in the pending lawsuit between the inhabitants of

Santiago Tlatelolco, with don Lúcas de Santiago, a native from the barrio of La Concepción, and the inhabitants of San Sebástian. The 1704 lawsuit concerned lands, ciénega (marsh) and the lake. The

.original decree is located at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, in the Aubin collection

Figure 2 Ordenanza del Señor Cuauhtemoc, ca. 1528

The manuscript was designed in the nature of a title-deed or an exposition of the towns’ rights over the lake, accompanied by cadastral maps of the historical divisions that were made throughout the preceding generations. With the goal of establishing solid grounds for remembrance, this canonic narrative shifts back in memory to the story of the foundation of the town of Tlatelolco, around 1360, and then moves to the state of things, as they were right after the conquest. In 1523, following

Cuauhtemoc’s statute (ordenanza), Charles V of Spain recognized don Diego de Mendoza

Imauhyantzin, Cuauhtemoc’s son, as a direct heir to Motecuhzoma’s property. That included Lake

Ecátepec, San Cristóbal Ecatepec, Tacuba, Chontalpa, Meztitlan, Juchipila, Jalisco, Chalco Atenco,

Cozcatlan, Tenamutla, Teposcolula, Ayacapan, Tezcamacoyo and Chilapan, as well as the permanent government of the towns of Santiago Tlatelolco and Chilapan.5 In 1560, don Diego had undergone a process of residencia in Santiago Tlatelolco before don Estéban de Guzmán, after a native qualified judge from Xochimilco, interrogated his acts of expropriating lands back in 1557.6 The figure of the judge appears in the Códice de Tlatelolco (folio 7, for the years 1558-9), on the right side of this page, on the bottom.7 In the Chimalpahin Codex, we get an account of the judge’s term of office in

Tenochtitlan; it began in June 1554 and ended in January 1557.8 The Códice was what don Diego had undertaken to produce in order to justify his acts. The pictorial, cartographic version was of the former rulers, the major religious and political institutions, the wars won, the succession of the rule, and the lands owned by his forefathers. In what followed, don Luis de Velasco reinstated him as the governor of Santiago Tlatelolco and made him the proprietor of the lands, part of which was contested in the 1572 litigation by don Juan Luis Cozcatzin. The Tenochca Emperor’s address is in the form of a legacy left by his distant ancestors, of their customs and instructions, which he was now ready to pass on to his people, so as to be able to cope better with the rapidly changing circumstances.9 He calls upon his people to cherish this historical heritage, to preserve its values, to provide for local necessities, and resist any future encroachment of the Lake.10 The style contained here is an amalgam of the reverential speech-style huehuehtlahtolli [“words of the elders”], combined with Nahua traditional forms of royal instructions, land claims, recitations, as well as oral histories enacted in performances of songs. Not a few of them remained during the early 1520s and 1530s basically traditional, and orally-transmitted texts that were thereafter fitted into Spanish-Christian contexts after the conquest.11 Their process of change into the new contexts, nevertheless, did not

.shatter the ongoing process of imparting and disseminating such cultural, cognitive schemata

Intertwining conquests

One of the songs in the Cantares Mexicanos, “A Song of Green Places”, describes the historic bloody journey, back in 1363, of the Mexica, through Tepaneca lands and their forced settlement, as

Azcapotzalco’s vassals, across the lake, in Tenochtitlan-Tlatelolco. As in Cuauhtemoc’s address, the overall mood is gloomy, deeply pessimistic and grim. The obvious function of the historic recalling of those ancient times is to reenact and combine the circumstances of captivity, anguish and humiliation under the Azcapotzalco rule socially memorialized, with the later state of the Spanish conquest, thus, it was closer to what had already been experienced in the past. Episodes from the distant past are also closely interwoven and identified with episodes of the present, and the traumatic

:fate reflected in both becomes one

Where do we go, where do we go to die, do we yet have life? Is there yet a place of pleasure, yet a“ pleasure land, O Life Giver? Delicious flowers, songs, perhaps, are only here on earth. Let them be

12 ”!our riches, let them be our garment. Ah, with this be well-pleased

:Cuauhtemoc’s address to his people begins in a similar manner

Here we inscribe and allocate [where] we are seated, according to the manner in which we are“ located, [by] The great Lake, its color [is that] of a tiger’s skin, its waves are like-silver, and it shines like gold, so fragrant and odorous. Where we found our town of Tlatelolco, where we rest and where we are engaged in the building of our town, [the endeavor of which] had cost us, the

Mexicans, many hardships, to make it come true. Formally established, we should never lack anything in our homeland, in Tlatelolco, nor should one be able to take away [from us our lands] or

13”…ever desire them Then the author moves to highlight the oral way by which memory of this local history was traditionally recorded and communicated among the elders of the town, and then passed on to the

:next generations [huehue cuicatl= “old men’s song”]. This part merits our special attention

They recalled in themselves what they felt in their hearts, of the hardships and adversity that they“ had undergone, singing with great sorrow and tenderness a sonorous song; the elders, and ancestors of Tlatelolco played their instrument, the teponastli, coated with silver, and enameled with precious

14”.stones

What immediately comes to mind is, clearly, the familiar style resonated and inspired by the

Cantares mexicanos . The narrative then goes on to address the times when the territory was finally pacified, political differences were settled and government and authority were properly established

[omosonglalique= “have been established”] in Tlatelolco by the chosen ruling dynasty.15 One major historical factor related to this narration is that, in 1473, Tlatelolco was finally subjugated by the

Tenochca, and it had lost its independent status of tlatocayotl, of being ruled by its own ruler.

Cuahutemóc relates how back in the year Four Reed (1431), his Chichimeca ancestors left as a bequest a pictorial illustration delineating the lake and assigning land and water to the fishermen of

Tlatelolco.16 On this lienzo, the most prominent historical figures who ruled over Tlatelolco are depicted. This legacy left by the Chichimeca forefathers [que ansí lo dejaron puesto los viejos ancianos antiguos], of the limits and the different uses of the Lake was guarded as well as and transmitted by the local fishermen to the local rulers by way of “guidance”.17 The fishermen

(michpipilo, in Nahuatl), were fishermen of canes/reeds, who also enjoyed the status of “owners of the lands”. They allocated the space for various activities, such as fishing and the cultivation of reeds, and they guarded the limits against foreign invasions.18 Cuhautemoc possibly refers to the Lake’s partition made in 1435 by Itzcoatl, after he finally broke the power of the western Tepanecas, back in

19.5 Flint, 1432, with the approval of Cuauhtlatoa, the then ruler of Tlatelolco, who is mentioned here One could, perhaps, juxtapose such a representation with parallel representations of the Chichimec ancestors that appear in the late colonial, indigenous, Techialoyan paintings. For example, the early eighteenth-century Techialoyan Códice de San Pedro Tototepec [foja 6 recto], as well as the Códices de Tzictepec, Tepotzotlan, Ocoyacac and Tetelpan, and the first part of the Códice Garcia Granados, vividly depict these Chichimeca ancestors [achcocoli; yacanpantli] and their mythological leader,

Xolotl. They appear in a semi-nude form, wearing leather loincloths, long hair, and are equipped with bows and arrows. This closely resembles what Chimalpococa describes in his Historia Chichimeca:

Sólo cuero tenían por vestidura. Sólo con heno ellos se cubrían. And in Nahuatl: zan eua tlaquemitl. zan pachtli in quimoqetiaya.20 They appear to be frozen in time, forever to be memorized [ypanpa zemicac machiztitoz= “and forever it will be explained”; or, ah ypanpa zemicac machiztitoz yn itzinpeucan= “and forever it will be transmitted ever since its origins”], as was in the original dictated by the ancient records, such as the Códice Xolotl. 21 All of them also refer to the independent histories

[annals] of the rulers of Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco ever since their origins, as independent rulers, the empowerment of Tlatelolco by the Tenochca in 1473, and the end of their joint dependency around 1560. The final division of the Lake was thereafter established between the great rulers of

Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco, and Texcoco’s rights and jurisdiction were apparently discontinued, as it is explained. Cuahutemóc describes how he saw to it that three special guardians were to be positioned on top of the tallest mountains surrounding the lake, Coyote and Albarrada, at the site called Tzapinco. Their duty was to watch over the boundary line [nenemi coaxochtli] dividing the

.territory between Texcoco and Tlatelolco, so that there would not occur any intrusion across

These data could well be interpreted here as innate models or constructs upon which memory was collectively imparted through the process of memorability; within them, also, one can clearly identify particular sites/apparatuses inserted within the text, that play the role of “memory beacons”. One of such memory beacons were the techialoyan, that is, an “observation tower,” built on the shore of

Lake Texcoco as a strategic structure from which the waters were watched. The depiction of the site is compatible with what is entailed in the Códice Tchialoyan de San Antonio la Isla. 22 This part, containing sixteen folios, ends up with a depiction of King Cuauhtémoc, seated on a icpalli [back mat], with a banner behind him and, in the middle, are nine heads/ figures of the fishermen for whom the “map” was made. The following part, which possibly pertains to the early eighteenth century and is very similar in content to the Techialoyans, is an “explanation of the map”, as was told by the elders of the town of Santa Catalina. It begins with: “Here we are adjusting and marking the boundaries of the Lake, that belong to us, that which were left and granted to us our ancestors, and that Quauhtlatohuatzin, the first king of Tlatelolco, assigned to them…” Reading the source one gets a clear sense of how, by the eighteenth century, such narrative containing separate pieces of the past, pertaining to three different eras, could eventually be taken over by the people of Santa Catalina and be interwoven and maintained to make a whole, coherent schema, based upon both pictorial and oral accounts and testimony. Their own account comes to an end with the assertion that, “there they had

23.”left the depiction of hands pointing towards where our boundary markers are placed

Around the Lake Texcoco area, what also becomes a major essence that heavily impressed upon memory restructuring, in its collective form is, nevertheless, the conflictive, ambivalent relationships forming between former dependents and allies.24 In the aftermath of the conquest, the entire area came, naturally, under ongoing power contests and trials of re-appropriation. Former, dependent districts mentioned in the Tlatelolco-Ecatepec lawsuit, as those of Acalhuacan, Coatitlan, and

Tolpelac were originally subjects of Tlatelolco. In 1531, its governor and nobility were still trying to re-appropriate these places after they had been placed by Cortés (in 1527) under the encomienda granted to Leonor de Motecuhzoma. How fragile and shaky was the situation and power-balance in major areas around Tenochtitlan, even ten years after the conquest, is attested in the Anales de

Cuauhtitlan; according to these, Chiconahutla and Ecatepec, although tributaries of Motecuhzoma

[tequihuaque= “tributaries”] remained under their own tlatoani until the Spanish conquest, and the local rulers in Chiconahutla and in Ecatepec were, Tlaltecatl and Paintzin, respectively.25 As the early lawsuits conducted between Tlatelolco and its ex-dependencies indicate, the lords of Tlatelolco, in effect, continued to ignore Leonor's rule, and compelled the local lords and inhabitants to remain loyal to them only, and to refrain from rendering tributes or services to either Leonor or to Christóbal

.de Valderrama, the ex-visitador general of the Royal Council of the Indies in Spain

Conclusion

The attitude of the indigenous elite in Tlatelolco toward the Spanish conquest vis-à-vis the previous

Tenochca conquest of their ethnic state (back in 1473), as in the above case of the former Coixca province in the State of Guerrero, shows a strong presence of cognitive schemata that serve as coping mechanisms. They helped the local elders in Tlatelolco to reconcile these different conquests into a coherent plot of the past that attempts to overcome fragmentation and chaos. How these local elders associate these different conquests with each other, as well as their different symbolisms and power representations in order to establish a seemingly coherent plot of the past that should overcome fragmentation and chaos is what these constructs are all about. How to deal with the similarities and differences between various conquests and subordinations lied, in this case as in others, in the context of major verbal components that, when linked, established repeated patterns and thus created schemata. That is, when connected, they are inseparable from the cognitive constructs utilized to deal with the transformations that took place under colonial rule. The “task” faced by the native witnesses was essentially to consolidate and re-build entire schemata out of the new-old modes of rulership.

One should further note that in their own litigation the lords of Tlatelolco emphasize their autonomy from Motecuhzoma, and their rule separate from that of the greater Tenochtitlan. Almost ten years after the conquest. The lords of Tlatelolco were in effect ignoring Leonor de Motecuhzoma's rule, compelling the local lords and inhabitants to remain loyal only to them and to refrain from rendering tribute and services to Leonor and Christóbal de Valderrama. They were subject to His Majesty only, not to any other encomendero. In the past, they claimed, they had rendered a particular service to

Motecuhzoma as his vassals, but were never part of his patrimony. As the rest of the inhabitants of

26.Mexico, they had also recognized Motecuhzoma's rule and jurisdiction, but not over their lands

In the course of the hearings, the legal representative of the town of Ecatepec, based his rhetoric upon conceptual essences taken from the Salamanca debates on the "Just War". The time in question was thus divided between the “time of the pagans” and the “time of the Christians”; he thus emphasized that, "what had been justified in pagan times could no longer be accepted under the permissible post-

".conquest circumstances. No rule, once an acceptable norm, could now be taken for granted Also, Mundy, “Mapping the Aztec Capital: The 1524 Nuremberg Map of Tenochtitlan, Its Sources and 1

.Meanings.” Imago Mundi 50 (1998): 11-33

.The Essential Codex Mendoza (F. Berdan, ed.,), 147 2

.Gerhard, A Guide to the Historical Geography of New Spain, 182 3

Cédula dada por el emperador Quauhtemotzin para el reparto de la laguna grande de Tescuco en 1523 4

.((Biblioteca Aportación Histórica. México D.F. Editores Vargas Rea, 1943

.Ordenanza del Emperador Carlos V, 1592...,” AGN Tierras, vol. 3, exp. 1“ 5

.Perla Valle, Códice de Tlatelolco,estudio preliminario, (INAH-UNA, Puebla, 1994), fols. 1 and 8 6

.Còdice de Tlatelolco 7

.Codex Chimalpahin, Vol. 2, 41 8 selos dejo a los hijos esto para que sepan como alcanzaron esta tierra los antiguos nuestros … 9

.antepasados y abuelos nuestros

.Cédula dada por el emperador Quauhtemotzin, fol. 16 10

See, for example, on the Nahua sacred drama, Louise M. Burkhart, Holy Wednesday, A Nahua Drama 11 from Early Colonial Mexico (University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 1996); on the pre-Columbian sacred hymns of the the various indigenous groups in Mexico see, Miguel León-Portilla, Pre-Columbian

Literatures of Mexico (University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1969), Chapter 2; John Bierhorst, trans. and

.(ed., Cantares Mexicanos: Songs of the Aztecs (Stanford University Press, Stanford, 1985

.A Song of Green Places”, Cantares mexicanos, 347“ 12

Aquí ponemos y asentamos en la forma que hallamos la Laguna grande como atigrada,: sus olas como 13 plata y brillante como el oro tan fragante y oloroso, donde fundamos nuestro pueblo de Tlaltelulco donde descansamos o hacemos nuestra fundación del pueblo que nos ha costado muchísimos trabajos para deberlo de alcanzar nosotros los Mexicanos, y para ponerlo formalmente a que nunca falte esta nuestra patria aquí

.en Tlaltelulco y que nadien pueda quitarselos ni codiciarselos nunca se acordaron en sí lo que en su corazón sentían por los trabajos y desdichas que havían padecido, “ 14 cantaron con gran tristeza y tenura un sonoro canto lo viejos antiguos de Tlaltelulco tocaron su instrumento

”.engarasado de plata, y esmaltado en ricas piedras, el que llaman teponastli

Y en este tiempo pusieron o eligieron el que ha de ser Señor de ellos, o el que los havía de governar, y 15

.entonces sosegraron sus corazones los mexicanos. Cédula dada por el emperador Quauhtemotzin, fol. 14

Que fué en el año que reinaban las cuatro cañas, que los antiguos tenían por su calendario, que viene a … 16

.ser el de mil cuatrocientos y treinta y un años y nos llevaron los pescadores en sus canoas, y les fuimos enseñando y apuntando con el dedo de la … 17

.mano

See, the use of this term and its pictorial associations in, Nadine Béligand, Códice de San Antonio 18

Techialoyan A701Manuscrito Pictográfico de San Antonio la Isla, (Estado de México, Institúto Mexiquense

.de Cultura, México, 1993), 52

.Códice de Tlatelolco, 33 19

.Chimalpococa, Historia Chichimeca (México, 1950), 28 20

In the Códice Cozcatzin, fol. 3v, one gets a very similar account to that of the above, possibly based upon 21

.one common, oral and pictorial source. Even the style and wording are almost the same

.Códice de San Antonio Techialoyan A701, ibid 22

.Ibid., fol. 17 23

The close marriage ties between the two lineages of Ecatepec (Ehecatepec) and Tenochtitlan formed an 24 integral part of this complexity. See, the “Various High Tenochca and Tlatelolca Lineages”, Codex

Chimalpahin, (Vol. 2, 101, 101; P. Carrasco, “The Territorial Structure of the Aztec Empire”, in Harvey

.(edit.), Land and Politics, 100

.Anales de Cuauhtitlan, fol. 83 25

.AGI Justicia, leg. 125, fol. 1289r 26