Contracts I - Wilmarth (2002) -modified Box outline

Is There A Contract? I. Mutual Assent A. Objective Theory – In evaluating whether a contract exists, the test is objective, NOT subjective. 1. Is There Mutual Assent? - A true interpretation of an offer or acceptance IS NOT what the party making it thought it meant or intended it to mean, but what a reasonable person in the parties’ position would have thought it meant. a. Ray v. Eurice Bros. – A party is bound to a signed document which he has read with the capacity to understand it absent fraud, duress, and mutual mistake. Hand’s “20 Bishops” example b. Park 100 v. Kartes – A contract is invalid if the acceptance was obtained by fraud.

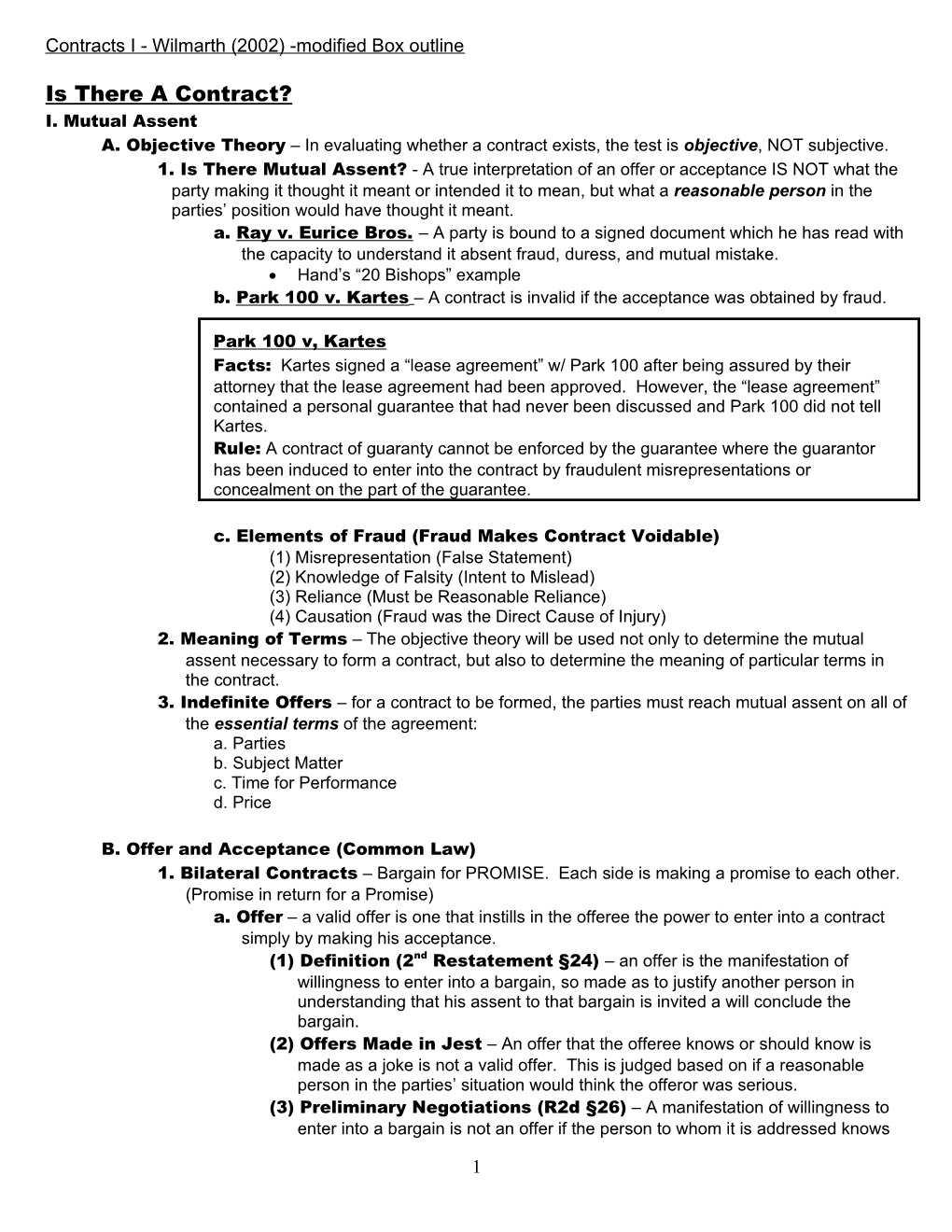

Park 100 v, Kartes Facts: Kartes signed a “lease agreement” w/ Park 100 after being assured by their attorney that the lease agreement had been approved. However, the “lease agreement” contained a personal guarantee that had never been discussed and Park 100 did not tell Kartes. Rule: A contract of guaranty cannot be enforced by the guarantee where the guarantor has been induced to enter into the contract by fraudulent misrepresentations or concealment on the part of the guarantee.

c. Elements of Fraud (Fraud Makes Contract Voidable) (1) Misrepresentation (False Statement) (2) Knowledge of Falsity (Intent to Mislead) (3) Reliance (Must be Reasonable Reliance) (4) Causation (Fraud was the Direct Cause of Injury) 2. Meaning of Terms – The objective theory will be used not only to determine the mutual assent necessary to form a contract, but also to determine the meaning of particular terms in the contract. 3. Indefinite Offers – for a contract to be formed, the parties must reach mutual assent on all of the essential terms of the agreement: a. Parties b. Subject Matter c. Time for Performance d. Price

B. Offer and Acceptance (Common Law) 1. Bilateral Contracts – Bargain for PROMISE. Each side is making a promise to each other. (Promise in return for a Promise) a. Offer – a valid offer is one that instills in the offeree the power to enter into a contract simply by making his acceptance. (1) Definition (2nd Restatement §24) – an offer is the manifestation of willingness to enter into a bargain, so made as to justify another person in understanding that his assent to that bargain is invited a will conclude the bargain. (2) Offers Made in Jest – An offer that the offeree knows or should know is made as a joke is not a valid offer. This is judged based on if a reasonable person in the parties’ situation would think the offeror was serious. (3) Preliminary Negotiations (R2d §26) – A manifestation of willingness to enter into a bargain is not an offer if the person to whom it is addressed knows

1 or has reason to know that the person making it does not intend to conclude a bargain until he has made a further manifestation of assent. (a) Solicitation for Bids – a solicitation for bids is NOT an offer, it is simply preliminary negotiations. (b) Statement of Future Intent – an announcement by a person that he intends to contract in the future will not usually be considered an offer. (4) Price Quotations – Look at the following factors to determine if a price quotation is an offer. (a) Quantity – In order for a price quote to be an offer it MUST state a clear QUANTITY. (b) Addressee – In order for a price quote to be an offer it MUST be addressed to a particular person. (c) Terms – If the quote specifically states that it is ONLY a “quote” then it is unlikely to be considered an offer. (d) Need for Further Expression of Assent – If the quote says that all sales need to be approved, or uses similar language indicating that the person does not have the power to close the deal, it is NOT an offer. (5) Advertisements - In general, advertisements are not considered offers but there are some exceptions. (a) Specific Terms or Promises – If the advertisement contains words expressing a commitment to sell a particular number of units or to sell them in a particular manner, there may be an offer. (b) Conditional Offers – Some J/D consider “first come first served,” provisions in advertisements to constitute an offer. (6) Example – Lonergan v. Scolnick

Lonergan v. Scolnick Facts: placed an ad advertising the sale of property, inquired about the land and sent a form letter indicating the price and where the land could be found. inquired again asking for a description of the land and about an escrow agent, and replied that he had better act fast. (First come, first served implication) Rule: Before a contract can be formed, there must be a meeting of the minds of the parties as to a definite offer and acceptance. Comments: The court felt that the newspaper ad and the form letter were not offers b/c they were open to a number of people and weren’t specific to . Also, they felt that even though the last letter could have been seen as a conditional offer (first come, first serve), since wasn’t the first, he has no binding contract. b. Acceptance – in order for an acceptance to be valid, it must be made to someone intended by the offeror to have the right to accept and it must become effective during the time in which the offeree still has the power to accept. (1) Definition (R2d §50) – Acceptance of an offer is a manifestation of assent to the offer made by the offeree in a manner invited or required by the offer. a. With Bilateral Contracts, the offeree must take every step required to MAKE THE PROMISE in order to accept the offer. (2) Mailbox Rule (R2d §63) – The acceptance of an offer is made when it is placed in the mail, regardless of whether the offeror receives the acceptance or not. a. Offeror can get around the mailbox rule by stating in the offer that an acceptance is not valid until they receive it.

2 (3) Qualified Acceptance/Counter Offers (R2d §59) – Any return of an offer where changes are made IS NOT an acceptance; it constitutes a counter offer that must then be accepted by the original offeror. (4) Option Contracts – When Bilateral Offers have a stated time period (e.g. “Offer open until Friday at 5pm”), they create a revocable option where the offeror can still revoke the offer at any time before the offer is accepted. (The mailbox rule applies to acceptance). However, after Friday at 5pm, the offeree no longer has the power to accept the offer. If the offeree provides consideration to the offeror to ensure that the contract is open until Friday at 5pm, the offer becomes irrevocable until Friday at 5pm, AND, the mailbox rule no longer applies to acceptance, the offer is only accepted when the offeror RECIEVES the acceptance (R2d §63(b)) (5) Terminating Power of Acceptance (R2d §36) – the offeror’s power of acceptance can be terminated by: (a) Rejection (§38) or Counter Offer (§39) - if offeree rejects an offer or makes a counter offer (see above), he can no longer accept once the rejection or counter offer is received by the offeror (§40). (b) Lapse of Time – If the offeror did not set a time limit, a “reasonable” time limit will be implied. (c) Revocation – Offeree loses the power of acceptance if the offer is revoked before it is accepted. (Offer is not revoked until offeree receives the revocation) (d) Death or Incapacity – The power to accept is ended upon the death or incapacity of the offeror or offeree c. Revocation – An offer can only be revoked if the revocation is communicated to the offeree before the offer is accepted. A revocation is only considered valid when it is received by the offeree. d. Example – Normile v. Miller Normile v. Miller Facts: made an offer to and responded w/ changed terms. The offer was revoked before had accepted, but the time period stated on the original offer had not run yet. Rule: If a seller rejects a purchase offer by making a counteroffer, which is not accepted, the prospective purchaser does not have the power to accept the counteroffer after receiving notice of the counteroffer’s revocation. Comments: This case illustrates that a conditional acceptance = a counteroffer which can be revoked by the offeror at any time before it is accepted by the offeree. 2. Unilateral Contracts – Bargain for PERFORMANCE. Not a mutual promise, a promise of a reward is offered in exchange for performance. a. Offer – An offer to enter into a unilateral contract is made when one party makes a promise to do something if the other party performs a certain act, however the offeree is under no duty to perform that act and they may decide whether or not to do so. b. Acceptance – A unilateral contract offer is accepted only by full performance by the offeree. c. Revocation (1) Classical Theory – under the classical theory of contract law, an offer for a unilateral contract could be revoked at any point prior to full performance. (Brooklyn Bridge Example) Petterson v. Patberg Facts: made a unilateral offer to that if a mortgage was paid by a certain time then there would be a discount on the mortgage. made the first required payment and made arrangements to acquire the rest of the $. When went to to pay the $, revoked the offer before could pay. 3 Rule: An offer to enter into a unilateral contract may be withdrawn at any time prior to the full performance of the act requested to be done. Comments: In the Restatement 2d, part performance makes the offer irrevocable, but actual performance is required, preparation to perform is not enough although this may constitute detrimental reliance for a PE claim. (2) Restatement 2d §45 – Part Performance – According to the Restatement, once the offeree begins the invited performance, the offer becomes a binding option contract, which makes the offer temporarily irrevocable. a. Actual performance is required; preparation to perform isn’t enough, although this may be enough for a PE claim (detrimental reliance).

b. The completion of the performance still must be made w/in the terms of the contract for the offeree to have officially accepted the contract. 3. Silence as Acceptance (R2d §69) – Silence can be an acceptance when: a. Offeree takes the benefit of services w/ reasonable opportunity to reject them and w/ reason to know that they were offered in the expectation of compensation. (1-sided modifications don’t count) b. Offeror has stated or given reason that silence will constitute assent. c. Offeree should know that silence means acceptance due to prior dealings. Cook v. Coldwell Banker Facts: CB made a bonus offer to employees that was accepted by performance (unilateral offer). They later changed the period of the bonus and then said that was not entitled to the bonus b/c she quit before the end of the new bonus period (but before the end of the old bonus period). Rule: In the context of an offer for a unilateral contract, the offer may not be revoked when the offeree has accepted the offer by substantial performance. Comments: The second bonus offer was a revocation of the first bonus offer and the court ruled that the first bonus offer could not have been revoked w/o express assent b/c had made substantial performance, which made the first offer a binding option contract. Her silence did not indicate an acceptance to the second offer (above factors were not met). 4. Employee Handbooks as Contracts – Employee handbooks are generally considered to be unilateral offers, which are accepted when the employee works knowing about the handbook. a. Best Offer – in general, the employees are entitled to the best offer from a handbook while they were working unless they expressly consented to any changes in the handbook. Duldalo v. St. Mary of Nazareth Hospital Facts: alleged that St. Mary’s breached the promises set out in the employee handbook barring termination of permanent employees w/o progressive disciplinary procedures. Rule: And employee handbook or other policy statement creates enforceable contractual rights if the traditional requirements for contract formation are present. Comments: Employee handbooks are now considered to be binding statement of the rights and duties of both the employees and the employer. 5. Authority – in order for an offer to be valid and enforceable upon acceptance, the offeror must have the authority to make the offer. a. Three Types of Authority (1) Actual – there is a written document giving the offeror authority to make the offer.

4 (2) Actual Implied – If something has become a custom or a form of conduct that shows that a person usually has authority, you can assume that the person has authority in that situation. (3) Apparent – If someone makes it apparent to others that someone has authority, they can reasonably assume that the person has the authority, even if they don’t.

II. Consideration – in order for a promise to be enforceable, there must be consideration. A. Bargain Element – to constitute consideration, a performance or a return promise must be bargained for. (R2d §71(1)) 1. Definition (R2d §71(2)) – A performance or return promise is bargained for if it is sought by the promisor in exchange for his promise and is given by the promisee in exchange for that promise. 2. The Following may Constitute Consideration (R2d §71(3)) a. An act other than a promise b. A forbearance of a LEGAL right c. The creation, modification or destruction of a legal relationship d. Signed legal waiver 3. Who Gives/Receives Consideration? – the performance or return promise may be given by the promisee or some other person to the promisor or some other person. 4. Motive or Inducement (R2d §81) – Mixed motive is allowed. If the primary motive is to make a gift, it doesn’t matter as long as there is some sort of compensation involved as well. (e.g. Aunt gives $3000 promissory note as a gift, but also asks for a silver dollar for her collection.)

B. Benefit/Detriment Test – to determine if there is adequate consideration, look and see if the promisee does something that is a benefit to the promisor or does something that is a detriment to him. 1. Pre-Existing Duty (R2d §73) – If the acts performed by the promisee that provide a benefit to the promisor are things that the promisee is already required to do by law, then they do not constitute adequate consideration. 2. Forbearance of Rights – In some cases, giving up rights can be a detriment to the promisee, but only if the promisee is giving up LEGAL RIGHTS. If what they are giving up is something that they’re not allowed to do anyway, then it does not constitute adequate consideration. Hamer v. Sidway Facts: Uncle promised to give his nephew $5000 on his 21st birthday if he would forbear from the use of liquor, tobacco, swearing, or playing cards or billiards form money until his 21st birthday. Rule: In general, a waiver of any legal right at the request of another party is sufficient consideration for a promise. Comments: In this case the court found that the uncle truly wanted his nephew to refrain from these things and it was therefore a benefit to him as well.

3. Conditional Gifts – conditions that must be met can sometimes constitute consideration if they are something that the promisor truly wants. a. Condition Must Benefit Promisor – in Plowman v. Indian Refining Co., ’s claimed that having to go pick up their checks was consideration for getting the payments but the court said that got no benefit from them picking up the checks, nor did they get a detriment (if anything, ’s got a benefit), so it was just a conditional gift and did not constitute consideration. b. Altruistic Pleasure – altruistic pleasure is not enough of a benefit to the promisor to constitute adequate consideration. (e.g. Rich guy telling a bum that if he walks around the corner to the store he can buy a coat on the rich guy’s credit is not consideration b/c 5 rich guy is indifferent as to whether the bum walks to the store or not. ) (However, Scrooge’s actions could be considered to be enforceable due to consideration b/c he benefited from doing good.) 4. Settlement of Claims (R2d §74) a. Valid Claims - If the promisee gives up valid claims or defenses against the promisor, this constitutes adequate consideration. b. Invalid Claims – Giving up invalid claims or defenses CAN constitute consideration ONLY when the promisee honestly believes that the claims are valid. c. Waivers – The execution of a written waiver to claims or defenses that is made by someone who had NO DUTY to do so constitutes consideration IF IT IS BARGAINED FOR, even if the promisee wouldn’t have asserted the claim or thought the claim was invalid.

Baehr v. Penn-O-Tex Facts: found out that had taken over a gas station where rent was due to . promised that the rent would be paid and said that his forbearance to sue constituted consideration to make the promise enforceable. Rule: While forbearance to bring suit is deemed consideration, there must be some showing that the forbearance was bargained for and was not merely conveniently granted unilaterally by one party. Comments: The court found no forbearance b/c Pennotex did not ask to forbear, and they felt like really only waited to sue until it was convenient for him. possibly could have made a restitution claim against b/c they benefited from his stations w/o paying.

5. Nominal or Sham Consideration – Purely nominal consideration (like giving someone $3000 in return for $1) is usually an indication that there was no bargain at all and that it was a gift.

Dougherty v. Salt Facts: ’s aunt gave him a promissory note promising to pay him $3000 either before her death or on her death for “value received.” Rule: A note that is not supported by consideration is unenforceable. Comments: The court found that previous services did not constitute consideration and that the “value received” note was sham or nominal consideration. The aunt was simply making a gratuitous gift which is not enforceable.

C. Past Consideration – When a promise is made in consideration for past services or benefits previously received the consideration is not sufficient to bind a promisor to the promise. However, in some cases the promisee may have a promissory restitution claim against the promisee.

Plowman v. Indian Refining Co. Facts: ’s were told that they would receive ½ of their salary w/o working and there was a dispute as to how long this was supposed to continue. The payments were stopped and the ’s sought to enforce the agreement saying that their many years of service and having to go pick up their checks was consideration. Rule: Past services are not sufficient consideration to support the enforceability of a contract to provide continuing payments to former employees.

6 Comments: The court also felt that going to pick up the checks was a condition on a gift that did not benefit the promisor so therefore it was not consideration.

D. Inadequate Consideration (R2d §79) – Once it has been determined that adequate consideration exists, there are no additional requirements. The exchange does not have to be equivalent and there does not have to be “mutuality of obligation”. Mere inadequacy of consideration DOES NOT void a contract.

Batsakis v. Demotsis Facts: loaned 500,000 drachmae (equal to $25 in American money) in return for a promissory note to pay $2,000 in American money. Rule: Mere inadequacy of consideration does not void a contract. Comments: Inadequacy of consideration may provide evidence for proving fraud, duress or undue influence, but it does not, in and of itself, void a contract.

7 Obligation in the Absence of Exchange Promissory Estoppel Looks FORWARD to a future benefit and DETRIMENTAL RELIANCE on that FUTURE BENEFIT (Look at DETRIMENT to ) Promissory Restitution Looks BACKWARD to a past benefit and gives compensation for that PAST BENEFIT (Look at BENEFIT to )

I. Promissory Estoppel: Protection of Unbargained-for Reliance - must show that they relied upon ’s promise to their detriment. A. Detrimental Reliance – in order to apply PE to enforce a promise w/o consideration, MUST PROVE DETRIMENTAL RELIANCE!!! 1. Restatement Definitions a. Option Contracts (R2d §87(2)) – a bilateral offer can become a binding option contract, even w/o consideration, if the offeror should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance of a substantial character on the part of the offeree before acceptance and this does in fact occur. b. Promises Inducing Action or Forbearance (R2d §90(1)) – a promise that the promisor should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance on the part of the promisee or a 3rd person and which does induce such action or forbearance is binding even w/o consideration. c. Avoiding Injustice – both §87(2) and §90(1) say that the offer or promise will only become binding in these situations only if injustice can be avoided by enforcement of the offer or promise. d. Elements of PE in 2nd Restatement §90 (1) Unilateral Promise (2) Reasonably FOS Reliance by Promisee (3) Detrimental Reliance (4) Injustice can ONLY be Avoided by Enforcement 2. Promises Within the Family – It is difficult, in many cases, to enforce promises w/in the family under traditional contract rules (mutual assent and consideration) because they are usually gratuitous promises. However, promises w/in the family can be enforced if it can be proven that the promisee detrimentally relied upon the promise. a. FOS/Reasonable Reliance (Ricketts v. Scothorn) – when a person reasonably relies upon a promise to their detriment, if the reliance was FOS, the promise is enforceable, even if it was gratuitous.

Ricketts v Scothorn Facts: ’s grandfather promised to pay her $2000 @ 6% interest a year so she wouldn’t have to work. She was not required to stop working, it was her choice, but she did stop working for some time in reliance on the promise. When her grandfather died, his executor () refused to enforce the promise. Rule: A gratuitous promise is enforceable if it is reasonably relied upon by the promisee to their detriment and this reliance is FOS. Comments: This court does not actually use promissory estoppel; they say that they are stretching equitable estoppel and tried to say that they were enforcing misrepresentations when they were actually enforcing a promise

b. Oral Promises Inducing Actions (Greiner v. Greiner) – Oral promises resulting in the genuine assumption of a promise that induces considerable actions are enforceable if injustice can only be avoided by the enforcement of the promise.

8 Greiner v. Greiner Facts: offered her son an 80-acre tract of land if he moved back to this land that was owned by her. moved his family, gave up his old house, and made substantial improvements on the land. His mother had made statements saying she wanted to give him the deed to the land, which she later rescinded, and he sued. Rule: Promises reasonably inducing definite and substantial actions are binding if injustice can be avoided only by the enforcement of the promise. Comments: In this case, there was no written promise to give the deed to the land, but the court felt that it was sufficiently promised and that relied upon this promise to his detriment by moving his family and spending time & money to make improvements to the land.

c. Promises Implied by Conduct (Wright v. Newman) – Voluntary conduct can imply a promise to care for another that is binding if relied upon to their detriment.

Wright v. Newman Facts: had been living w/ for 10 years and had been caring for her and her two children, one of which was not his. ’s actions had implied his promise to take care of them. When they separated, sued for child support for both children. Rule: A promise to which the promisor should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance on the part of the promisee or a 3rd person and which does induce such action or forbearance is binding if injustice can be avoided only by the enforcement of the promise. Comments: In this case, the promise to provide support was implied by his act of listing himself as the father on the birth certificate of the child and his continued actions for 10 years.

3. Charitable Subscriptions – Promissory Estoppel provided courts with a way to enforce charitable gifts that were obviously gratuitous and w/o consideration. a. Cardozo and the Allegheny College Opinion – When a promisor requires ANYTHING in exchange for a charitable gift there is consideration. (1) PE v. Consideration – in this case, there were strong facts for PE and a weak rule (PE wasn’t really acknowledged in NY yet although Cardozo seems to think that it was), but there was really no detrimental reliance. With consideration, there was a strong rule but weak facts and Cardozo stretches the idea of consideration to fit this case.

(2) Introducing PE – Cardozo introduces the idea of PE and what is required for it in order to influence future decisions although his decision in Allegheny College is based on consideration rather than PE. Allegheny College Facts: Mary Johnston made a pledge to give Allegheny College $5000 that was payable w/in 30 days of her death to be used for ministry students under a fund in her name. She gave them $1000 of the pledge before her death, and on her death the Bank refused to give Allegheny College the rest of the $. Rule: When the promisor requires that the promisee do anything in exchange for the promise there is adequate consideration present when dealing w/ charitable contributions. Comments: Cardozo raised the issue of PE w/ the detriment being that AC was limited in their freedom to use this money, but he decided the case on the basis that the $1000 deposit created a binding bilateral agreement required them to start a fund in her name.

9 b. Promissory Estoppel Recognized and Applied (Congregation Kadimah Toras-Moshe v. DeLeo) – PE is allowed to enforce charitable gifts if ’s can prove reasonable detrimental reliance.

Congregation Kadimah Toras-Moshe v. DeLeo Facts: ’s husband had promised, in front of witnesses to give the congregation $25,000 and his wife would not pay after his death. Rule: Promissory Estoppel can only apply to charitable pledges when there has been substantial detrimental reliance on the promise, a hope or expectation, even if well founded, is not equivalent to either legal detriment or reliance. Comments: They also said that there could be no consideration under Cardozo’s analysis b/c there was no discussion or indication of how the money was to be used.

4. Commercial Context – The doctrine of PE has been applied to commercial situations where employers make promises to pay pensions or when at-will jobs are promised. a. Pensions – In situations where the promise of a pension is made under terms allowing the employee to retire, the doctrine of PE has been used to enforce these promises when there is detrimental reliance. Detrimental reliance can include retiring before necessary and giving up salary, not looking for other employment, etc. Katz v. Danny Dare Facts: was offered a pension (after 13 months of negotiation) and then decided to retire. After 3 years said that he had to come back to work in order to receive the pension $. Rule: The application of the doctrine of PE does not require the relinquishment of a legal interest. Comments: In this case, the court found that detrimentally relied on the pension $ by giving up his full salary and not looking for another job.

***In Hayes v. Plantations, it was found that PE didn’t apply to situations where pensions were promised after retirement b/c the retirement was not in reliance on the pension$***

b. At-Will Jobs – Courts generally hold that when someone is promised an at-will job, the employer is not free to withdraw the promised job when the person has detrimentally relied on the promise by quitting their previous job, turning down other job offerings, moving, etc.

II. Restitution: Liability for Benefits Received – Restitution is an equity doctrine that arises when A confers a benefit on B expecting compensation. With restitution, there does not have to be an agreement OR a promise. A. Restitution in the Absence of a Promise a. In General – generally, to determine if a restitution claim exists, you need to look at the motive of the in doing what they did and if there was an unjust enrichment to . (1) Factors to Consider (a) Benefit to - was benefited by ’s services (b) Compensatory Intent – when performed the services, his intent MUST HAVE BEEN to be COMPENSATED, if his intent was purely gratuitous or charitable, then there is no claim for restitution (c) Knowledge of Compensatory Intent – a reasonable person in ’s situation should have known that expected compensation. (d) Unjust Enrichment – it is unjust/inequitable for to retain the benefit w/o compensating . 10 (2) Reasonable Person Standard – Use a reasonable person standard to determine if intended to be compensated.

Sparks v. Gustafson Facts: Gustafson managed Sparks’ property and often paid for things out of his own pocket. 2 years after Sparks died, Gustafson sued for compensation for his services. Rule: If a reasonable person would have intended to be compensated in a given situation, then there is a restitution claim by . Comments: Basically, the court said that Gustafson’s acts went above and beyond what would be expected as gratuity from a friend and therefore a reasonable person would have expected compensation. b. Saving Life or Health Without Consent (Restatement of Restitution §116) A person who has supplied things or services to another w/o being able to obtain their consent is entitled to restitution in the following circumstances: (1) Acted w/ the Intent to Charge (2) Actions Prevented Serious Bodily Harm or Pain (3) No Reason to Know That the Person Wouldn’t Have Consented if They Were Able. (If mentally competent) (4) Impossible for to Give Consent Examples (1) Doctor treating an unconscious patient is entitled to restitution b/c could not agree and a reasonable person would have agreed. (2) Violinist who plays outside a window is not entitled to restitution b/c they could have obtained consent and didn’t. c. Saving Property Without Consent (Restatement of Restitution §117) A person who has preserved things belonging to another from serious damage or destruction w/o being able to obtain their consent is entitled to restitution in the following circumstances: (1) Possession of ’s Things was Lawful (2) Situation was Not Created by ’s Breach of Duty (3) Reasonably Necessary to Render the Services Before Being Able to Obtain ’s Consent. (4) No Reason to Know Would Not Have Wanted Him to Act (5) Intent to Charge (6) Things Have Been Accepted by the Owner After Being Recovered d. Within the Family (1) Unmarried Cohabitants – Many courts that do not recognize common law marriage have allowed restitutionary claims for unjust enrichment by one of the parties when the other received benefits from them throughout their cohabitation and did not compensate them upon separation. The argument made is that even if cohabital relationships when people are unmarried are unlawful, it is unfair for one party to retain all the benefits of the relationship and the other to get nothing b/c they are equally at fault.

Watts v. Watts Facts: Upon the termination of her non-marital cohabitation w/ , sought to recover a fair proportion of their accumulated assets and property. Rule: Unmarried cohabitants may raise claims based upon unjust enrichment following the termination of their relationships where one of the parties attempts to retain an unreasonable amount of the property acquired through the efforts of both.

11 Comments: Unjust enrichment is based on proof that (1) a benefit was conferred on by , (2) knew of or appreciated the benefit, and (3) accepted the benefit under circumstances making it inequitable for to retain the benefit w/o compensating . (2) Caring For Elderly Parents a. General Rule – the general rule is that there is a presumption that any services rendered by family member to each other are presumed to be gratuitous, while services rendered b/t individuals who are not members of the same family are presumed to be for compensation.

b. Same Family Requirement – the requirement that parties are part of the same family depends on circumstances rather than just kinship. If an adult comes back home to live w/ their parent and for the purpose of rendering services of an extremely burdensome nature over a long period of time, there is no presumption of gratuity. c. Presumption is Rebuttable – this is a rebuttable presumption, but courts differ on what must establish to overcome the gratuity presumption. e. Remedies (R2d §371) a. Fair Value of Services – in cases where ’s services provided a benefit to , the remedy is usually the fair/reasonable value of their services. b. % of Wealth Increase – in some cases, the remedy determined by a % of the increase in ’s wealth due to ’s benefits to .

B. Promissory Restitution – services rendered w/ a subsequent promise of compensation that is relied upon. 1. 2nd Restatement: Promise For Benefit Received (R2d §86) – a promise made in recognition of a benefit previously received by the promisor from the promisee is binding to the extent necessary to prevent injustice. (When looking at preventing injustice, look at the benefit to rather than the detriment to ) a. Factors to Consider (1) Compensatory Intent - §86 is not applicable if the promisee intended the benefit as a gift. Promisee MUST HAVE a compensatory intent. (2) Unjust Enrichment – promisor MUST HAVE been UNJUSTLY ENRICHED or else §86 does not apply. (3) Proportionality of Benefit to Promise – the promise can only be enforced to the extent that the value promised is reasonably proportionate to the benefit received by the promisee. (e.g. promise to pay $1 million b/c someone returned your missing hamster is disproportionate) b. Moral Obligation – In general, a moral obligation does not constitute a promissory restitution claim unless receives a MATERIAL BENEFIT. (1) Moral Obligation NOT ENOUGH ( Mills v. Wyman) - MAJORITY RULE: a moral obligation IS NOT sufficient consideration to support a promissory restitution claim. (This allows courts to avoid going into the uncertain field of morality because there are so many difficulties and differences in determining what is a moral obligation as opposed to what is a legal obligation.)

Mills v. Wyman Facts: took care of ’s son w/o being requested to and promised to compensate him for the expenses arising out of the care. then later refused to pay and sued under promissory restitution. Rule: A moral obligation is insufficient as consideration for a promise.

12 Comments: This case probably would not have been decided differently under the material benefit rule b/c the benefit was to ’s adult son and not to directly so it was not material. If ’s son had been a minor, the benefit would have been sufficient b/c would have been relieving of a legal duty to care for her son.

(2) Material Benefit (Webb v. McGowin) – MINORITY RULE: a moral obligation CAN constitute sufficient consideration to support a promissory restitution claim when receives a MATERIAL BENEFIT.

Webb v. McGowin Facts: saved from severe bodily injury or death by placing himself in grave danger and subsequently suffering grave bodily harm. , in return, promised compensation and ’s executors refused to pay after ’s death 8 years later. Rule: A moral obligation is a sufficient consideration to support a subsequent promise to pay where the promisor has received a material benefit. Comments: In cases where a promise is one that most citizens would have kept, and the court feels that enforcement is just, a few courts will enforce the promise using this MATERIAL BENEFIT rule.

------

Obligation in the Absence of Complete Agreement I. Limiting the Power to Revoke: Pre-Acceptance Reliance A. General Contractor/Sub Contractor Problem – a problem arises when a sub-contractor submits a bid to a general contractor, who relies on that bid in their master bid, and then the sub- contractor realizes that there was a mistake in the bid. Can They Revoke The Bid?? 1. Consideration – Judge Hand initially said in Baird v. Gimbel Bros., that there is no consideration for the sub-contractor’s bid because the general contractor is not promising to use the sub-contractor’s bid if they receive the job. Most Courts still follow this rule, but they use PE to enforce these bids.

2. Promissory Estoppel – Since no consideration can generally be found in these cases, most courts will apply PE to protect the GC’s. a. Old Rule (Hand – Baird v. Gimbel Bros.) – Hand said that PE didn’t apply because there was no mutuality and it was unreasonable for the GC to assume that the SC intended to enter into a 1-sided obligation, so therefore it was unreasonable for GC to rely on SC’s bid.

b. Modern Rule (Traynor – Drennan v. Star Paving) – Traynor said that SC’s knew that GC’s would rely on their bids and therefore if the reliance was reasonable (if GC’s had no reason to know there was a mistake) then the SC’s bid was irrevocable until GC had a reasonable chance to notify SC of their acceptance of SC’s bid. (Follows §87(2), §90, and §45)

c. Exceptions to Modern Rule (1) If SC’s bid EXPLICITLY states that it is revocable until accepted (2) If SC’s bid is OBVIOUSLY the result of a mistake then reliance is not justified. (3) If GC uses inequitable conduct such as “bid shopping” while claiming that other bidders are bound (4) If GC uses inequitable conduct such as “bid chopping” (attempting to re- negotiate the bid w/ SC) then SC bid is void. 13 B. Option Contracts and Promissory Estoppel (R2d §87(2)) – Options with Bilateral Contracts that are revocable b/c not supported by consideration CAN BE binding under §87(2) if there is reasonable detrimental reliance by the offeree. 1. Bilateral Offers are Enforceable as Option Contracts w/o Consideration When: a. Promisor reasonably expected the promisee to rely on the promise b. Promisee reasonably relied on the promise c. Failure to enforce the promise would result in perpetuation of fraud or result in other injustice.

2. Example: No Reasonable Reliance (Berryman v. Kmoch)

Berryman v. Kmoch Facts: (Berryman) entered into an agreement w/ (Kmoch), a real estate agent who wrote the agreement, to sell land and the agreement said that the offer had a 120 day option which was to be supported by $10 consideration. The $10 was never paid by Kmoch (), and when wouldn’t sell the land, argued that his expenditures of time and money in attempting to attract buyers constituted consideration to support the enforceability of the option. Rule: An agreement that lacks consideration may be enforceable based on PE when the promisor reasonably expected the promisee to rely on the promise, the promisee reasonably relied on the promise, and the only way to avoid injustice is through the enforcement of the promise. Comments: In this case, the court determined that there was no reasonable reliance on the option b/c was a real estate agent, he wrote the agreement, and he KNEW that the option was not binding w/o paying the consideration.

C. Implied Promises and Promissory Estoppel (Broad Application of R2d §90) 1. Repeated Assurances and Constitute an Implied Promise – When one party repeatedly assures another party that certain things will occur, even if there is never an explicit promise made, PE can apply when one party reasonably relies on the assurances. This applies to assurances during negotiations that a contract will be made. 2. Example: Reliance on Assurances is Enough for PE (Pop’s Cones) Pop’s Cones Facts: was a TCBY franchisee and they relied upon the assurances made by Resorts Hotels () that the agreement to move their store would be finalized. Resorts repeatedly assured them that the agreement was almost finalized and encouraged them not to re-sign the lease on their old store. relied on these assurances and then sued when the agreement fell through. Rule: Assurances can constitute an implied promise, and can be enforces under PE when reasonably expects them to induce actions or forbearance by ; the assurances do induce such actions or forbearance, and the only way to avoid injustice in with the enforcement of the implied promise. 3. What Kinds of Assurances are Enforceable? – Not all assurances are considered to be enforceable under PE as implied promises. Assurances that are deemed to be simply “expressions of intention,” “opinions,” or “predictions” are not usually deemed sufficient to invoke PE. 4. Sophistication of Parties – The relative sophistication of the parties involved can also make a difference. Courts are more reluctant to stretch §90 in cases where the parties doing the negotiations were lawyers or bankers, or other sophisticated agents. Courts are more open to stretch §90 in cases where one of the parties is in a subordinate bargaining position or is the “little guy”.

D. Reliance Damages – The damages that ’s are allowed to recover in most of these cases are “reliance damages,” or basically what the gave up, spent, or lost as a result of their reliance on ’s 14 promises or assurances. (e.g. In Pop’s Cones, Pop’s received the additional cost they incurred in buying a new store location and the expenses involved in finding a new location.)

II. Binding Option Contract in the UCC: The “Firm Offer” A. “Firm Offer” (UCC §2-205) 1. An offer is not revocable under the UCC, even if there is NO CONSIDERATION, when it is: a. Made by a Merchant (§2-104 defines merchant – EXPERTISE) b. To Buy or Sell Goods (§2-105 defines goods – TANGIBLE, MOVEABLE ITEMS) c. In a Signed Writing (§1-201(39) – Any symbol made w/ an intent to authenticate) d. Gives Assurance that it will be Held Open 2. When Firm Offers are Irrevocable: a. During the Time Stated b. If no Time is Stated then for a Reasonable Time c. NEVER MORE THAN 3 MONTHS

3. Oral Offers – According to UCC §2-205, the offer MUST BE WRITTEN to constitute a firm offer. ORAL OFFERS do not qualify under the firm offer provision. However, under §1-103, common law principles can be used to invoke promissory estoppel under §87(2) or §90 w/ oral offers.

B. Acceptance Under the UCC (UCC §2-204) OLD – Acceptance can be made in any manner sufficient to show agreement INCLUDING CONDUCT.

C. Requirements Contracts – Requirements contracts are agreements where one party agrees to purchase all his required goods or services from the other party exclusively for a specified time period for a stated price. However, in the absence of a requirements contract, each sale of a product to a purchaser carries its own contractual terms that can be accepted through CONDUCT (e.g. Accepting the goods).

D. Preservation of Rights (UCC §1-207) OLD – A party can assent to a contract while reserving the right to contest the terms of the contract at a later date. (Terms such as “under protest” or “without prejudice” are sometimes used)

E. “Firm Offer” v. Restatement 2nd §87(2) and §90 – The difference b/t UCC §2-205 and §87(2) and §90 of the 2nd Restatement is that the “firm offer” rule does not require detrimental reliance of any sort to constitute a binding option.

F. Example: Mid South Packers v. Shoney’s Mid South Packers v. Shoney’s Facts: accepted meat shipments from at a price higher than it thought was appropriate and then deducted the amount from its payment of the last shipment. Part of the original agreement had stated that would inform of price increases w/ 45 days notice. Then when ordered the meat, told them that there had been a 10 cent price increase. Rule: In the absence of a requirements contract, each sale of a product to a purchaser carries its own contractual terms. Comments: This was not a requirements contract, so at best it was a firm offer that expired after the first sale b/c the next sale constituted a new contract. Each sale thereafter was therefore based on the new price, which Shoney’s paid w/o reserving the right to later contest. Therefore, Shoney’s consented to the new price by its conduct in continuing to order and receive each shipment.

III. Qualified Acceptance: The “Battle of Forms” 15 A. Common Law (“mirror image” rule) – If any terms in the acceptance differ from terms in the offer, it is not an acceptance at all but rather a counter offer. 1. “Last Shot” Problem – the mirror image rule creates the “last shot” problem where each time a term is altered, it is considered a counter offer rather than an acceptance, which causes the last “counter offer” that was exchanged to be binding if the general agreement is carried out b/c their conduct will establish acceptance. Therefore, one party can add an additional term and if the other party buys or sells goods w/o completely re-reading the contract, they are bound to the new terms. Poel (letter was counter-offer not acceptance)

B. NEW UCC §2-207 IF: 1) parties recognize existence of contract though not in records; -or- 2) contract formed by offer + acceptance; -or- 3) contract confirmed by a record that has different terms than another confirmed contract THEN (subject to parol evidence allowed in UCC §2-202) terms are those that: 1) appear in records of both parties; -and- 2) which both parties agree, whether in record or not; -and- 3) are supplidor incorporated under UCC. IV. Postponed Bargaining: The “Agreement to Agree” A. Traditional View – option contracts are not enforceable unless all the essential terms (such as price) are agreed upon or based upon an objectively verifiable source that a court can use to determine these terms. (Walker v. Keith) 1. Variation to Traditional Rule – this traditional rule is NOT A UNIVERSAL RULE, some courts do try to use reasonable measures to set essential terms such as price by making “reasonable” judgments as to value, rental, etc. based on the market or values of similar property.

B. UCC View – The UCC takes a MUCH BROADER view of Open Terms 1. Open Terms Allowed (UCC §2-204(3)) – this provision says that even though one or more terms are left open a contract for sale does not fail for indefiniteness if the parties have intended to make a contract and there is a reasonably certain basis for giving an appropriate remedy. 2. Open Price Terms (UCC §2-305) – Under the UCC, there can be a contract when the price is not settled. a. Reasonable Price at Time of Delivery – the price is set to be the reasonable price at the time of delivery if: (1) Nothing is said about the price (2)The price is left to be agreed upon and the parties fail to agree (3) The price is to be set based upon some market or other standard as set by a 3rd person and it is not set. b. Good Faith – a price to be fixed by the seller or buyer means a price for that party to fix in good faith. c. Fault – when the price is not fixed due to the fault of one party, the other party may treat the contract as cancelled or fix a reasonable price himself. d. No Intent to Be Bound – if the parties DO NOT INTEND to be bound unless the price is fixed or agreed upon, and the price is not fixed or agreed upon, there is NO CONTRACT.

C. Common Law View (2nd Restatement §33) – The common law view is somewhat like the UCC but it is stricter than the UCC because it requires reasonable certainty. 1. Reasonable Certainty Requirement – Even when the intention is to make an offer, it cannot be accepted to for a contract unless the terms of the contract are reasonably certain.

16 a. When are Terms Reasonably Certain? – The terms of a contract are reasonably certain when they provide a basis for determining the existence of a breach and for giving an appropriate remedy.

b. Open Terms – The fact that one or more terms are left open or uncertain may show that the parties did not intend to be bound. (No offer or acceptance) 2. Conservative J/D – In conservative J/D, courts WILL NOT reach out to enforce agreements. 3. Liberal J/D – In liberal J/D, courts WILL be more likely to reach out and enforce agreements by filling in open terms.

D. Letters of Intent – With letters of intent, there are 3 different things the parties might mean: 1. Preliminary Terms Have Been Worked Out But We are NOT BOUND – in these cases, the parties can still walk away and they are not bound even to the terms that are written down. a. Need To State Intention Explicitly – If this is what parties mean w/ a letter of intent, they’d better SAY IT or WRITE IT DOWN because modern courts will not take this view unless it is explicitly stated. 2. Letter is a COMPLETELY BINDING Deal – in these cases, the completion of the agreement is a formality and they are bound by their signature on the letter of intent. This interpretation is most often used when all major parts of the contract are in the letter of intent and the parties have otherwise acted to infer that there is a binding contract. a. Sometimes a Jury Question – if there is competing evidence on both sides as to the intent of the parties, the question is left to the jury. Arnold Palmer v. Fuqua Facts: and entered into negotiations for to sell ’s products, wrote a memorandum of intent that said it was conditional upon its acceptance by both companies but they also made a press release confirming the agreement. Rule: When all of the main terms for an agreement are contained in a letter of intent and the actions of the parties otherwise indicate that a binding agreement has been formed then the agreement CAN be binding, if there is conflicting evidence it is a jury question. Comments: The court said in this case that it can’t be said as a matter of law that didn’t have a case, even thought ’s letter was conditional b/c of ’s actions and the substance of the letter of intent.

Pennzoil/Texaco Case Facts: Pennzoil and Getty entered into an oral agreement, which was confirmed in a memorandum of agreement that was subject to approval by the companies. Getty made a press release about their agreement w/ Pennzoil, and then entered into negotiations w/ Texaco. The merger w/ Texaco was finalized and Pennzoil sued Texaco. Rule: If the actions of the parties indicate that a binding agreement has been formed, then a jury can find that a contract existed. Comments: In this case, the court felt that the press release by Getty showed there was a deal, and they were also aware that Texaco didn’t go into this blind. Texaco knew there was a deal w/ Pennzoil and pursued the deal w/ Getty anyway and they tried to indemnify themselves of liability to Pennzoil.

3. Letter Binds the Parties to Negotiate in GOOD FAITH – in these cases, if they don’t reach a deal, they don’t have a binding agreement, but they are required to use good faith in negotiating the deal. The courts will look at whether good faith measures were used to reach a final agreement, the court can compel the parties to bargain, and damages are often awarded to the party who can prove that the other did not act in good faith. 17 ------

The Statute of Frauds I. Common Law A. Does the Contract Fall Within the SOF? (R2d §110(1)) 1. In General – the following classes of contracts are subject to the SOF unless there is a written memorandum or an applicable exception: (a) Executor/Administrator Contracts (Wills) (b) A contract to answer for the debt or duty of another (c) Marriage Agreements and Pre-Nuptial Agreements (d) Real Estate Transfers (leases, etc.) (e) A contract that is not to be performed w/in one year form the making thereof (one-year provision) 2. One Year Provision (R2d §130) – Where the promise in a contract CANNOT be fully performed w/in a year from the time the contract is made, all promises in the contract are w/in the SOF until one party completes his performance. a. Completed Performance – when one party to a contract has completed his performance, the one-year provision of the SOF does not prevent enforcement of the promises of other parties. b. Liberal Interpretation – there is a liberal interpretation of the 1-year provision. If the contract could POSSIBLY be performed in a year, even if it is unlikely, then the SOF doesn’t apply. (1) Notice Period – If there is a provision for a notice period w/in 1 year then SOF doesn’t apply. (2) Lifetime Contracts – lifetime contracts are NOT w/in the SOF b/c the person can die w/in a year. (3) Right to Terminate – If either party has the right to terminate the agreement w/in a year then SOF doesn’t apply (4) Breach of Contract –if there is NO WAY to get out of the contract w/in a year w/o BREACHING the contract then SOF applies.

B. Is There a Written Memorandum With a Signature? 1. Required Elements (R2d §131) – a contract w/in SOF is enforceable if it is evidenced by ANY WRITING, signed by or on behalf of the party to be charged, which: a. Reasonably identifies the subject matter of the contract b. Is sufficient to indicate that a contract has been made between the parties or offered by the signer. c. States with reasonable certainty the essential terms of the contract. 2. Several Writings (R2d §132) – The memorandum used to satisfy the SOF may consist of several writings if one of the writings is signed and the writings clearly indicate that they relate to the same transaction. Party being charged must have agreed to the memos unsigned by them either through express assent or conduct (e.g. allowing to work, memo coming from their office, etc.) 3. Signature (R2d §134) – The signature can be any symbol made or adopted w/ an intention to authenticate the writing as that of the signer. a. Kroger letterhead and authorized name can be = signature. b. Parma Tile automatic printing of name on a fax signature.

4. Example – Crabtree v. Elizabeth Arden Crabtree v. Elizabeth Arden

18 Facts: was hired by to be ’s sales manager. No formal contract was signed, but separate writings pieced together showed Crabtree to have been hired for a two-year term w/ pay raises after the first and second 6 months. When he did not receive his second pay raise, sued for damages from breach of contract. Rule: SOF does not require the memorandum expressing the contract to be in one document. It may be pieced together out of separate writings, connected w/ one another either expressly or by parol evidence showing they should be connected. Comments: In this case, the contract couldn’t have been performed in 1 year so SOF applied and the piecing together of the memos satisfied the SOF.

C. Is There an Exception? 1. Part Performance (Limited Exception – R2d §129) – This is a VERY NARROW exception that applies only to REAL ESTATE transfers (land) and only if you are seeking SPECIFIC PERFORMANCE and not $$$. a. Part Performance – if can show that they did something (e.g. improves land, etc.) in reliance on the promise then this can constitute part performance and equity will except the agreement from SOF it that is the only way that injustice can be avoided.

b. Still Have to Establish an Agreement – still has to show that there was an agreement in the first place. Getting around the SOF doesn’t mean you win the case, it just means that you get to MAKE YOUR CASE. 2. Promissory Estoppel (Broad Exception – R2d §139) – Applies §90 to SOF: a promise that the promisor should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance, which does induce such action or forbearance, is excepted from the SOF if injustice can be avoided only by the enforcement of the promise. a. Circumstances that Determine When Injustice is Avoided (1) Availability and Adequacy of other remedies such as cancellation and restitution (2) Definite and Substantial Character of the Action or Forbearance in Relation to the Remedy Sought (Detrimental Reliance) (3) Clear and Convincing Evidence that an Offer was made to Induce the Reliance. (Promisor had Authority) (4) The Reasonableness of the Reliance (Action or Forbearance) (5) Extent that Reliance was FOS by Promisor b. Difference Between §90 and §139 - §139 requires stronger evidence (clear and convincing evidence) than §90 (preponderance of evidence). c. Example: PE Justified – Alaska Democratic Party v. Rice - was promised a job that never materialized and there was detrimental reliance b/c she gave up a job, moved to Alaska. There were also no other alternative remedies, she had a good reason to believe that had the authority to make the promises he did b/c he was the candidate, her reliance was reasonable, and should have foreseen that would rely on his promises b/c he kept assuring her that it would work out even after the Party said he couldn’t hire her. Therefore, injustice can only be avoided by enforcement of the agreement according to §139(2). d. Example: PE Not Justified – Munoz v. Kaiser - moved to CA for a job but there was no detrimental reliance b/c he didn’t give up another job, he didn’t lose $, and he wanted to move to CA anyway.\

II. The Sale of Goods and the SOF: UCC §2-201 A. Does the Contract Fall Within the SOF? (R2d §110(2)) – the following classes of contracts are subject to the SOF under the UCC: 1. A contract for the SALE OF GOODS for the price of $500 or more. (UCC §2-201) 2. A contract for the sale of securities (UCC §8-319)

19 3. A contract for the sale of personal property not otherwise covered, where the remedy is >$5000 (UCC §1-206)

B. Signed Writing Required (R2d §2-201(1)) – a contract for the sale of goods for $500 or more is not enforceable unless there is some writing sufficient to indicate that a contract for sale has been made between the parties and signed by the party against whom enforcement is sought or by his authorized agent or broker. (Offer is ok) 1. Omission and Mistake – a writing is not insufficient to satisfy the SOF because it omits or incorrectly states a term agreed upon. 2. Quantity Required – the contract is not enforceable beyond the quantity of goods shown in the writing used to satisfy the SOF.

C. Merchants Exception– if w/in a reasonable time a writing in confirmation of the contract is received by one party and that party has reason to know of the contents of the confirmation, this confirmation is a sufficient memorandum to satisfy the signed writing requirement UNLESS the receiving party gives WRITTEN NOTICE of their OBJECTION to the contents of the confirmation w/in 10 DAYS after it is received. (Offer NOT OK) MUST SAY THERE IS NO DEAL

Bazak International v. Mast Facts: moved to dismiss ’s breach of contract action by saying that the purchase order forms that allegedly confirmed the parties’ oral agreement were not confirmatory documents under the UCC so they failed to satisfy the SOF. Rule: Annotated PO forms signed by the buyer, sent to the seller, and retained by the seller w/o objection w/in 10 days, fall w/in the merchant’s exception, satisfying the SOF writing requirement even w/o the seller’s signature.

D. Exceptions to Signed Writing Requirement – if there is no sufficient signed writing confirming the agreement but the contract is otherwise valid, it is still enforceable if: 1. Goods are specially manufactured for the buyer and they are not suitable for sale to others and the seller has made a substantial beginning of their manufacture. 2. The party against whom enforcement is being sought admits in his pleading, testimony, or otherwise that a contract for sale was made. 3. Goods which have been received and accepted OR for which payment has been made and accepted. ------

Contract Interpretation and the Parol Evidence Rule I. Principles of Interpretation A. Traditional View – used a subjective approach (“Peerless” Example an honest mistake = unenforceable contract); an actual “meeting of the minds” was required.

B. First Restatement View – used a purely external, objective approach. Drafters of the 1st Restatement felt that the subjective theory made contracts too hard to enforce and the objective theory was good b/c people should expect their words to be understood in accordance w/ their normal usage. Problem was that this caused contracts to be construed to contain interpretations that neither party meant it to have.

C. Modern Approach – the modern approach uses a modified objective approach. Two Questions: 1. Whose meaning controls the interpretation of the contract? 2. What was that party’s meaning? 20 D. Whose Meaning Prevails? – 2nd Restatement §201. 1. §201(1) – If both parties intend the same meaning, that meaning applies 2. §201(2) – If the parties attach different meanings and A knows or has reason to know that B’s meaning is different while B does not know and has no reason to know of A’s meaning then B’s meaning stands. 3. §201(3) – If the parties have different meanings and nether knows of the other’s meaning then no contract exists. Joyner v. Adams Facts: agreed to give a fixed rent for 5 years provided that developed the property w/in that time. had almost completely developed the property when the time was up with the exception of one lot where water and sewer lines had been installed but the building was not yet built. sued for $ owed in rent increases over the 5 years b/c failed to comply w/ his side of the agreement and argued that developed did not mean that the buildings had to be constructed. Rule: The determination of whether a party to a contract had knowledge of the other party’s interpretation is essential to properly enforce a disputed provision of an agreement. The contract should be enforced relative to the meaning of the innocent party; i.e. the one who did not know of the other’s meaning. Comments: In this case, the case was remanded to allow a jury trial where the jury was instructed that they needed to determine the parties’ knowledge of the other’s intentions at the time the agreement was made.

E. What was the Party’s Meaning? 1. Rules for Interpretation (R2d §202) a. §202(1) – Words and other conduct are interpreted in the light of all the circumstances, and if the principle purpose of the parties is ascertainable it is given great weight. b. §202(2) – A writing is interpreted as a whole, and all writings that are part of the same transaction are interpreted together. c. §202(3) – Unless a different intention is manifested: (1) Language is interpreted in accordance w/ its generally prevailing meaning. (2) With technical contracts, words are given their technical meaning. d. §202(4) – Course of performance is given great weight when it was agreed to w/o objection. e. §202(5) – Wherever reasonable, intentions of the parties are interpreted as consistent w/ each other and any relevant course of performance, course of dealing, or trade usage. 2. Restatement Standards of Preference in Interpretation (R2d §203) a. Reasonable > Unreasonable – An interpretation that gives terms a reasonable, lawful, and effective meaning is preferred over an interpretation that gives terms an unreasonable, unlawful or ineffective meaning. b. Weight is Given to Interpretation Sources as Follows: (1) Express Terms – Look at the terms themselves, their reasonable interpretation, and maybe introduce parol evidence. (2) Course of Performance – How they have dealt w/ each other before with this specific agreement. (3) Course of Dealing (§223) – How they have dealt w/ each other before with similar agreements. (4) Trade Usage (§222) – How other parties in the relevant trade would view these terms.

21 c. Specific Terms > General Terms – Specific Terms are given greater weight than General Language. d. Negotiated Terms > Boiler Plate – Separately Negotiated or added terms are given greater weight than standardized terms or other terms not separately negotiated. (Boilerplate terms given less weight) e. Interpretation against the Draftsman (R2d §206)

3. UCC Rules of Interpretation a. Course of Performance(§2-208) – Where the contract for sale involves repeated occasions for performance by either party w/ knowledge of the nature of performance and the opportunity for objection, any course of performance without objection shall be relevant to determining the meaning of the contract. b. Course of Dealing (§1-205) – a sequence of previous conduct between the parties to a particular transaction that can be regarded as similar enough to the current transaction to establish a common basis of understanding for interpreting their expressions and other conduct. c. Trade Usage (§1-205) – any practice or method of dealing having such regularity among the trade or vocation as to justify an expectation that it will be observed w/ respect to the contract in question. d. Consistency (§1-205) – whenever possible, express terms are to be interpreted as consistent w/ course of dealing and trade usage. 4. UCC Standards of Preference in Interpretation (UCC §2-208) a. Weight is Given to Interpretation Sources as Follows: (1) Express Terms (2) Course of Performance (3) Course of Dealing (4) Trade Usage

Frigaliment – What is Chicken? Facts: ordered a large quantity of “chicken” from , intending to buy young chicken suitable for broiling and frying, but believed, in considering the weights ordered at the prices fixed by the parties, that he order could be filled with older chicken, suitable for stewing only and terms “fowl” by . Rule: The party who seeks to interpret the terms of the contract in a sense narrower than their everyday use bears the burden of persuasion to show that interpretation, and if that party fails to support its burden, it faces dismissal of its complaint. Comments: In this case, Justice Friendly went through all the rues and preferences for interpretation and there was conflicting evidence on both sides so he decided that lost since they had the BOPersusion.

F. Adhesion Contracts (~boiler-plate contracts) 1. Modern Rule (C&J Fertilizer) – A provision of an insurance contract may not contravene the reasonable expectation of the insured. 2. Restatement Rule (R2d §211): Standardized Contracts – If the other party has reason to believe that the party manifesting assent would not have assented if they knew that the writing contained a particular term, that term is not part of the agreement.

II. The Parol Evidence Rule – Do we look just at the written contract or do we also look at extrinsic evidence? 22 A. General Purpose – The general purpose of the Parol Evidence rule is to prevent people from later reflecting on what words might have meant when they were used and using this to form a claim. (Inventive Reflection)

B. Traditional View – The classical approach to the parol evidence rule was that if a contract is complete then no parol evidence was allowed for additional provisions, but parol evidence was allowed to determine the meaning of ambiguous terms if the contract was ambiguous. MUST SHOW AMBIGUITY.

C. Modern View – Integration 1. Integration Generally (R2d §209) – where the parties reduce an agreement to a writing that reasonably appears to be a complete agreement, it is taken to be an integrated agreement unless it is established by other evidence that the writing did not constitute a final expression. (Parol Evidence can be admitted to prove an agreement was not an integration)

2. Complete Integration v. Partial Integration (R2d §210) >>>STEP 1 a. Complete Integration – a completely integrated agreement is an agreement adopted by the parties to be a complete and exclusive statement of the terms of the agreement. (e.g. MERGER CLAUSE) b. Partial Integration – an integrated agreement that is not a complete integration. (Most agreements are partial integrations) c. Judge Decision – whether an agreement is a complete or partial integration is to be determined by the court as a question preliminary to deciding interpretation of the agreement or the application of the parol evidence rule.

Taylor v. State Farm Facts: alleged that his bad faith tort claim against was not barred by a release he had signed where he gave up all contractual claims against . Rule: A judge must first consider the offered evidence and, if they find that the contract language is “reasonably susceptible” to the interpretation asserted by the party arguing for that interpretation then the evidence should be given to a jury to decide what the intention of the parties was. Comments: Basically, if there is evidence where 2 interpretations could possibly be drawn, then the evidence should be submitted to the jury to decide on the proper interpretation.

3. Integration and Parol Evidence (R2d §215, §216(1) AND UCC §2-202) >>> STEP 2 a. Complete Integration – allows parol evidence ONLY to show the meaning of terms or to suffice any of the exceptions. NO PAROL EVIDENCE OF ADDITIONAL TERMS. b. Partial Integration – allows parol evidence to show the meaning of terms and for CONSISTENT SUPPLEMENTAL TERMS, but NOT for contradictory terms. c. Non-Integration – allows parol evidence for EVERYTHING, including Consistent Supplemental Terms, Contradictory Supplemental Terms, and parol evidence to show the meaning of terms.

D. Exceptions to the Modern Parol Evidence Rule 1. Show Integration (R2d §214(a)&(b)) – Parol evidence can ALWAYS be used to show that an agreement is non-integrated or to show that an integrated agreement is a partial or a MOST complete integration. IMPORTANT EXCEPTION 23 2. Explain Meaning (R2d §214(c)) – Parol evidence can ALWAYS be used to explain the meaning of terms. This is interpreted broadly; parol evidence can be used to qualify terms or to make exceptions to terms, but NOT to negate terms.

3. Post-Contract Agreements – Parol evidence can ALWAYS be used to show conditions of agreements that were made AFTER the written contract was made. 4. Oral Condition Precedent (R2d §217) – When parties agree orally that the performance of the agreement is subject to the occurrence of a stated condition (e.g. Company President’s Approval), the agreement is not integrated with respect to the oral condition and can be invalid for failure to complete the condition. 5. Invalidity (R2d §214(d)) – Parol Evidence can ALWAYS be used to show invalidity due to fraud, duress, undue influence, mistake, incapacity or illegality. 6. Equitable Remedies – Parol Evidence can ALWAYS be used to show grounds for equitable remedies such as granting or denying rescission, reformation, specific performance, or other remedies. 7. Collateral Agreements (R2d §216(2)) – Agreements are NOT full integrations and therefore parol evidence can be used to show consistent additional terms if these additional terms are agreed to for separate consideration or are terms that may naturally be omitted from such a contract.

E. UCC Example – Nanakuli v. Shell – Under §2-202, parol evidence of course of performance, course of dealing, and trade usage can be used to qualify terms or to make exceptions to terms, but NOT to negate terms.

Nanakuli v. Shell Facts: contended that it had not breached its contract w/ by not price protecting because the contract said that the price would be ’s posted price at the time of delivery. provided evidence of course of performance that showed had price protected twice in the performance of this contract and trade usage evidence that price protection was a common practice among the trade. Rule: Trade usage and past course of dealings between contracting parties may establish terms not specifically enumerated in the contract, so long as no conflict is created with the written terms Comments: The court found that the price protection term was so prevalent in the concrete trade that it was reasonable for to believe that it was implicitly incorporated in the contract and ’s past history of price protection supported this finding.

------

The Obligation of Good Faith and Other Implied Terms I. Overview of Implied Terms A. Classical Approach – traditionally, courts were very reluctant to put words in people’s mouths, they felt that the parties should be able to reach a bargain on their own. 1. Traditional Rule – if one party is not bound to keep performing then the contract is unenforceable. 2. Example – DuPont v. Claiborne-Reno – There was not a specified term requirement for Reno’s distribution relationship w/ DuPont and the court said that if Reno could terminate the agreement whenever he wanted then so could DuPont.

B. Modern Approach – Courts have moved away from this classical approach to the point where they allow certain implied terms in order to make an agreement enforceable. 1. Implied Promises – modern courts have taken a different approach to cases where one party is seemingly not bound to the agreement where they have found that the party has made 24 an implied promise to use reasonable/best efforts in performing the contract in exchange for the express promise by the other party and therefore the contract is enforceable. a. Exclusive Dealing (UCC§2-306(2)) – A contract for exclusive dealing imposes an implied obligation on the seller to use best faith efforts to supply the goods and an implied obligation on the buyer to use best efforts to promote their sale. b. Example – Wood v. Lady Duff Gordon – Implied Promise Allowed

Wood v. Lady Duff Gordon Facts: received an exclusive right to endorse designs w/ ’ name and to market all her fashion designs for which she would receive ½ the profits derived. broke the contract by placing her endorsement on designs w/o ’s knowledge and sued. argued that did not promise to do anything and therefore the contract was unenforceable. Rule: While an express promise may be lacking, the whole writing may be instinct w/ an obligation, an implied promise, imperfectly expressed so as to form a valid contract. Comments: This is the leading case w/ implied promises where Cardozo shows the court’s willingness to imply promises in order to avoid the illusory agreement problem and the mutuality of obligation problem. In this case, Cardozo found that ’s promise to give ½ the profits implied a promise to use reasonable efforts in selling and marketing her designs. 2. Implied Reasonable Notification Requirement – in situations where at-will contracts are involved (those which can be terminated by either party at any time), modern courts tend to imply an obligation of reasonable notice when terminating the agreement. a. Reasonable Notice Requirement (UCC §2-309) – Where a contract provides for successive performances but is indefinite in duration it is valid for a reasonable time but can be terminated at any time WITH REASONABLE NOTICE given to the other party. b. Example – Leibel v. Raynor Manufacturing Co. – Reasonable Notice Requirement Implied.

Leibel v. Raynor Manufacturing Co. Facts: terminated an exclusive distribution agreement w/ w/o giving notice and sued saying that was required to give him reasonable notice so he could sell his existing inventory. Rule: Reasonable notification is required in order to terminate an ongoing oral agreement creating a manufacturer-distributor relationship. Comments: What exactly constitutes reasonable notice is not said in UCC §2-309, it will be up to a jury to determine what is considered reasonable notice.

II. Implied Warranties A. Good Title – not stolen property and no bank loans or other attached obligations

B. Non-Infringement – not infringing on someone else’s patent, trademark, copyright, etc.

C. Merchantability – goods are (1) of standard quality base on trade practice and (2) fit for the ordinary purpose of everyday use.

D. Fitness for a Particular Use – goods are fit for a particular use. Goes beyond merchantability from a general use to a specific purpose.

E. Habitability – leases will provide safe places to live, appliances work, etc.

25 III. The Implied Obligation of Good Faith A. Definitions of Good Faith 1. UCC a. §1-203 – Every contract or duty w/in the UCC imposes an obligation of good faith in its performance or enforcement.

b. §1-201(19) – “Good Faith” means honesty in fact in the conduct or transaction Good Faith concerned. Required Under Both UCC and c. §2-103(1)(b) – “Good Faith” in the case of a merchant means honest in fact and 2nd Restatement the observance of reasonable commercial standards of fair dealing in the trade.

2. 2nd Restatement a. §205 – Every contract imposes upon each party a duty of good faith and fair dealing in its performance and its enforcement.

B. Requirements Contracts – When requirements as to how much is bought/sold are set in contracts, these are considered to be “good faith” requirements. The buyer has an obligation to buy the products and the seller has an obligation to sell the products. Usually, requirements contracts are used to require the seller to sell a certain amount. 1. Rigidity of Requirements (UCC §2-306(1)) – in general, the estimate is not the controlling standard. a. Good Faith (§2-306(1)) – whenever an estimate is made to quantify the output of the The “good faith” seller or the requirements of the buyer, this estimate means such actual output or requirement is requirements as may occur in good faith. dominant where – the exception to the buyer buys b. No Unreasonably Disproportionate Quantities (§2-306(1)) less and the the “good faith” standard is that no quantity unrxbly disproportionate to any stated “unreasonably estimate or to any normal or otherwise comparable prior output (when there is no stated disproportionate” estimate) may be tendered or demanded. requirement is c. Estimate is Center (Comment 3 to §2-306) – Comment 3 says that the estimate dominant where is the center which leads one to believe that no quantity that is unreasonably MORE or the buyer buys LESS than the estimate will be allowed. more. (1) Excess Quantities Only – however, some courts hold the unreasonably disproportionate requirement to apply only to quantities in excess of the estimate. d. Buyer Shutdown (Comment 2 to §2-306) – Comment 2 says that the buyer can shutdown if they are acting in good faith. (1) Good Faith – courts have taken this good faith requirement to mean that the buyer must have a good faith reason for requiring the shutdown. (e.g. a shutdown for lack of orders might be permissible while a shutdown merely to curtail losses would not.) 2. Example – Empire Gas Co. v. American Bakeries – Unreasonably disproportionate provision does not apply to quantities that are less than the estimate, but the buyer must act in good faith, meaning they must have a good faith reason for deciding not to buy or to buy much less than the estimate. Empire Gas Co. v. American Bakeries Facts: agreed to buy all of its propane converters from under a requirements contract containing an estimate of 3,000 >or < for the number of converters that would buy. However, later decided that it did not need any converters and therefore they bought none and sued. Rule: A buyer in a requirements contract may decide to buy less than the contract estimate, or even to buy nothing, so long as the buyer acts in good faith, but good faith requires more than mere second thoughts about the terms of the contract. 26 Comments: In §2-306(1), the “good faith” requirement is dominant where the buyer buys less and the “unreasonably disproportionate” requirement is dominant where the buyer buys more.

C. Lender Liability – Courts are split on lender liability 1. Liberal Interpretation – Some courts say that even if a note expressly says “payable on demand,” there is an implied obligation of good faith. 2. Strict Interpretation – Other courts say that the express term is determinative and the implied obligation of good faith does not apply when the lender expressly reserves the right to terminate the loan at any time.