Hopkinson2019.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What to Make of Manny Pacquiao-Antonio Margarito?

What to make of Manny Pacquiao-Antonio Margarito? The Friday before last, Team Mayweather handed Bob Arum and Top Rank a bunch of lemons. Instead of trying to make lemonade, Arum passed the lemons off to boxing fans in the form of Manny Pacquiao vs. Antonio Margarito. Now it’s up to the boxing community to determine what to do with them. During his now-infamous conference call, Arum made it clear that his intentions were to pursue fights with possible opponents other than Mayweather, specifically Miguel Cotto or Margarito. Less than two weeks later the “Tijuana Tornado” emerged as the next opponent for the Filipino Congressman. In fighting Pacquiao (51-3, 38 KO) on November 13, Margarito (38-6, 27 KO) is receiving a “hand-wrapped” gift from Arum and Top Rank. In taking care of his own, Arum is granting Margarito what will most likely amount to the biggest pay day of his career. He is awarding “Tony” the chance of a lifetime simply for fighting under the Top Rank banner. During his conference call, responding to an inquiry about a potential Pacquiao-Tim Bradley fight, Arum immediately dismissed the possibility. “Tim Bradley is a tremendous fighter and he’s a great young man,” Arum said. “But the problem with a guy like Tim Bradley is that even though you and I know what a superb fighter he is, the public really doesn’t know.” He continued, “The other promoters don’t really promote their fighters. They take money from HBO or Showtime or a little Indian casino and they think they’re doing the kid a big service. -

Joshua Clottey Heads to Australia for Showdown with Anthony Mundine on April 2

JOSHUA CLOTTEY HEADS TO AUSTRALIA FOR SHOWDOWN WITH ANTHONY MUNDINE ON APRIL 2 NEW YORK: (March 6, 2014) Former world champion Joshua “The Grand Master” Clottey will head to Newcastle, Australia on APRIL 2 to clash with former two time WBA Champion and local favorite Anthony “the man” Mundine in a twelve round junior middleweight clash, it was confirmed today by Joe DeGuardia, Founder and President of Star Boxing. “It’s an excellent opportunity for Joshua, and we are glad that after extended negotiations with Brendan Bourke from BOXA Promotions this fight is officially on.” said DeGuardia. “He’s been training since his last victory in September looking for a big fight and Mundine presents a high risk/high reward type of fight. A win over Mundine will put him right back on track for a major fight in the United States.” “As a promoter we take pride in consistently providing our fighters with the best opportunities as we’ve also done most recently with world champion Demetrius Andrade, Chris Algieri and Delvin Rodriguez among others.” Sporting a record of 37-4-0 (22KO’s), Clottey comes off a ten- round shutout decision over Los Angeles based veteran Dashon Johnson on September 14, 2013 at The Paramount in Huntington, New York as part of Star Boxing’s acclaimed , “Rockin’ Fights” series. “I am now fighting at my best weight, 154 pounds, and Anthony Mundine is one stop on my road to the world championship” stated Clottey. With an outstanding fourteen-year career that includes wins over former world champions Zab Judah and Diego Corrales, Clottey is perhaps best known to New York City area boxing fans for his war for the ages with Puerto Rican superstar Miguel Cotto on June 13, 2009 at Madison Square Garden. -

He's Not Mayweather, but Joshua Clottey Might Be Good Enough

He’s not Mayweather, but Joshua Clottey might be good enough Timing and circumstances haven’t been kind to Joshua Clottey. He isn’t Floyd Mayweather, Jr., the welterweight everybody wanted to see against Manny Pacquiao on March 13. Instead, Clottey has been cast as the substitute, which to a cynical public only means he isn’t Mayweather and he doesn’t have a chance against Pacquiao on a night when Cowboys Stadium in the Dallas metroplex might be the biggest attraction. If he doesn’t feel like last season’s Detroit Lions or St. Louis Rams, then Clottey knows what it is to have been one of those replacement players in the last NFL work stoppage. In 1987, none of those guys belonged there and that’s exactly what you hear and read these days about Clottey. Pacquiao is supposed to kick him around like the soccer ball Clottey used to chase as a kid in Ghana. Fair? I don’t think so. Then again, I’ve been wrong about these things before. I actually thought Juan Manuel Marquez was skilled, smart and tough enough to challenge Mayweather. After watching Mayweather humble Marquez through 12 one-sided rounds in September, I wondered if I had been kicked in the head one too many times. Nevertheless, I like Clottey, perhaps not enough to pick him over Pacquiao, especially without a familiar trainer in his corner. He split with Kwame Asante after his loss by split decision in June to Miguel Cotto over a reported disagreement over money. Then, Godwin Kotay, also of Ghana, was denied a U.S. -

World Boxing Association Gilberto Mendoza

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF APRIL 2 009 th TH Based on results held from April 9 , 2008 to May 14 , 2009 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN Edificio Ocean Business Plaza, Ave. BARTOLOME TORRALBA (SPAIN) JOSE OLIVER GOMEZ E-mail: [email protected] Aquilino de la Guardia con Calle 47, JOSE EMILIO GRAGLIA (ARGENTINA) Oficina 1405, Piso 14 VICE CHAIRMAN ALAN KIM (KOREA) Cdad. de Panamá, Panamá GONZALO LOPEZ SILVERO (USA) Phone: + (507) 340-6425 GEORGE MARTINEZ E-mail: [email protected] MEDIA ADVISORS E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.wbaonline.com SEBASTIAN CONTURSI (ARGENTINA) HEAV YWEIGHT (Over 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) CRUISERWEIGHT (200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) LIGHT HEAVYWEIGHT (175 Lbs / 79.38 Kgs) World Champion:RUSLAN CHAGAEV (*) UZB World Champion: GUILLERMO JONES PAN World Champion: HUGO H. GARAY ARG Won Title: 09-27-08 World Champion: NICOLAY VALUEV RUS Won Title: 07-03-08 Won Title: 08-30-08 Last Mandatory: Last Mandatory: 11-22-08 Last Mandatory: Last Defen se: Last Defense: 11-22-08 Last Defense: 12-20- 08 WBC:VITALY KLITSCHKO- IBF:WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO WBC:GIACOBBE FRAGOMENI- WBO: VICTOR RAMIREZ WBC: ADRIAN DIACONU - IBF: CHAD DAWSON WBO: WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO IBF: TOMASZ ADAMEK WBO: ZSOLT ERDEI 1. KALI MEEHAN AUS 1. VALERY BRUDOV (OC) RUS 1. JURGEN BRAHMER (EBU) GER 2. TARAS BIDENKO UKR 2. GRIGORY DROZD (PABA) RUS 2. VYACHESLAV UZELKOV (WBA I/C) UKR 3. JOHN RUIZ (OC) USA 3. FRANCISCO PALACIOS (LAC) P.R. 3. ALEKSY KUZIEMSKI (EBA) POL 4. KEVIN JOHNSON USA 4. FIRAT ARSLAN GER 4. -

WBC International Championships

Dear Don José … I will be missing you and I will never forget how much you did for the world of boxing and for me. Mauro Betti The Committee decided to review each weight class and, when possible, declare some titles vacant. The hope is to avoid the stagnation of activities and, on the contrary, ensure to the boxing community a constant activity and the possibility for other boxers to fight for this prestigious belt. The following situation is now up to WEDNESDAY 9 November 2016: Heavy Dillian WHYTE Jamaica Silver Heavy Andrey Rudenko Ukraine Cruiser Constantin Bejenaru Moldova, based in NY USA Lightheavy Joe Smith Jr. USA … great defence on the line next December. Silver LHweight: Sergey Ekimov Russia Supermiddle Michael Rocky Fielding Great Britain Silver Supermiddle Avni Yildirim Turkey Middle Craig CUNNINGHAM Great Britain Silver Middleweight Marcus Morrison GB Superwelter vacant Sergio Garcia relinquished it Welter Sam EGGINGTON Great Britain Superlight Title vacant Cletus Seldin fighting for the vacant belt. Silver 140 Lbs Aik Shakhnazaryan (Armenia-Russia) Light Sean DODD, GB Successful title defence last October 15 Silver 135 Lbs Dante Jardon México Superfeather Martin Joseph Ward GB Silver 130 Lbs Jhonny Gonzalez México Feather Josh WARRINGTON GB Superbantam Sean DAVIS Great Britain Bantam Ryan BURNETT Northern Ireland Superfly Vacant title bout next Friday in the Philippines. Fly Title vacant Lightfly Vacant title bout next week in the Philippines. Minimum Title vacant Mauro Betti WBC Vice President Chairman of WBC International Championships Committee Member of Ratings Committee WBC Board of Governors Rome, Italy Private Phone +39.06.5124160 [email protected] Skype: mauro.betti This rule is absolutely sacred to the Committee WBC International Heavy weight Dillian WHYTE Jamaica WBC # 13 WBC International Heavy weight SILVER champion Ukraine’s Andryi Rudenko won the vacant WBC International Silver belt at Heavyweight last May 6 in Odessa, Ukraine, when he stopped in seven rounds USA’s Mike MOLLO. -

DE LA HOYA Vs. MAYWEATHER SUPER FIGHT MAY 5 at MGM GRAND in LAS VEGAS

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 20, 2006 DE LA HOYA vs. MAYWEATHER SUPER FIGHT MAY 5 AT MGM GRAND IN LAS VEGAS MGM Grand Garden Arena To Host Championship Title Bout LAS VEGAS – It will be an unprecedented super fight between two boxing superstars and former Olympians. It will be an event poised to shatter records many believe would never be broken. Golden Boy Promotions is pleased to announce six-division world champion Oscar De La Hoya will meet unbeaten, four-division world champion Floyd Mayweather Saturday, May 5 at MGM Grand in Las Vegas, Nev., in the biggest fight to hit the sport in decades. “This is what boxing is all about and fighting Floyd Mayweather is the type of fight that truly gets me motivated to go through a hard training camp and make the sacrifices I have to make to be the best,” said Oscar De La Hoya. “We’ve talked about it, the press and the fans have asked for it, and now we’re going to put it all on the line and fight. I can’t wait for May 5.” Floyd Mayweather followed by saying, “I’m excited to get this opportunity to once again show why I’m pound-for-pound the best in the world and to add another title to my collection. I respect everything Oscar has accomplished in this sport, but this time he’s in over his head.” Considering the pedigree of both De La Hoya and Mayweather, legitimate superstars with world- class credentials, this bout already is drawing comparisons to mega events of the past such as Leonard- Hearns, Hagler-Hearns, Ali-Frazier and De La Hoya-Trinidad. -

World Boxing Council Ratings

WORLD BOXING COUNCIL R A T I N G S RATINGS AS OF OCTOBER - 2016 / CLASIFICACIONES DEL MES DE OCTUBRE - 2016 WORLD BOXING COUNCIL / CONSEJO MUNDIAL DE BOXEO COMITE DE CLASIFICACIONES / RATINGS COMMITTEE WBC Adress: Cuzco # 872, Col. Lindavista 07300 – México D.F., México Telephones: (525) 5119-5274 / 5119-5276 – Fax (525) 5119-5293 E-mail: [email protected] RATINGS RATINGS AS OF OCTOBER - 2016 / CLASIFICACIONES DEL MES DE OCTUBRE - 2016 HEAVYWEIGHT (+200 - +90.71) CHAMPION: DEONTAY WILDER (US) EMERITUS CHAMPION: VITALI KLITSCHKO (UKRAINE) WON TITLE: January 17, 2015 LAST DEFENCE: July 16, 2016 LAST COMPULSORY: January 17, 2015 WBA CHAMPION: Tyson Fury (GB) IBF CHAMPION: Anthony Joshua (GB) WBO CHAMPION: Tyson Fury (GB) Contenders: WBC SILVER CHAMPION: Johann Duhaupas (France) WBC INT. CHAMPION: Dillian Whyte (Jamaica/GB) 1 Alexander Povetkin (Russia) 2 Bermane Stiverne (Haiti/Canada) 3 Kubrat Pulev (Bulgaria) EBU 4 Joseph Parker (New Zealand) OPBF 5 Johann Duhaupas (France) SILVER 6 Andy Ruiz (Mexico) NABF 7 Bryant Jennings (US) 8 Eric Molina (US) 9 Artur Szpilka (Poland) 10 Gerald Washington (US) 11 Carlos Takam (Cameroon) 12 Mariusz Wach (Poland) 13 Dillian Whyte (Jamaica/GB) INTL/BBB C 14 Dereck Chisora (GB) * CBP/BBB of C 15 Jarrell Miller (US) * CBP/P 16 Andrzej Wawrzyk (Poland) 17 Kyotaro Fujimoto (Japan) 18 David Price (GB) 19 Chris Arreola (US) 20 Dominic Breazeale (US) 21 Andriy Rudenko (Ukraine) INTL Silver 22 Charles Martin (US) 23 Oscar Rivas (Colombia/Canada) 24 Francesco Pianeta (Italy) 25 Trevor Bryan (US) NABF Jr. 26 Hughie Fury (GB) NA = NOT AVAILABLE 27 Amir Mansour (US) 28 Andrey Fedosov (Russia) Luis Ortiz (Cuba) WBA Interim Champion 29 Travis Kauffman (US) Lucas Browne (Australia) * NA - WBA 30 Robert Helenius (Finland) Wladimir Klitschko (Ukraine) * NA - IBF 31 Alexander Ustinov (Russia) Vyacheslav Glazkov (Ukraine) * NA - 32 Arnold Gjergjaj (Switzerland) Erkan Teper (Germany) * NA - Legal 33 Alexander Dimitrenko (Russia) Fres Oquendo (P. -

NEW NYC Cotto-Margar

WBA Super Welterweight Championship MIGUEL COTTO vs. ANTONIO MARGARITO II Saturday, December 3 at Madison Square Garden Presented Live By HBO Pay-Per-View® NEW YORK (September 20, 2011) -- This time it’s personal. Three-division world champion and the Pride of Puerto Rico MIGUEL COTTO will make the second defense of his World Boxing Association (WBA) super welterweight title in the long-awaited rematch against professional rival and three-time welterweight world champion ANTONIO “The Tijuana Tornado” MARGARITO, of México, Saturday, December 3, at The Mecca of Boxing, Madison Square Garden. Cotto-Margarito II will be produced and distributed Live by HBO Pay-Per-View® beginning at 9:00 p.m. ET / 6:00 p.m. PT. Their first encounter, on July 26, 2008, was a battle of epic proportion and arguably the Fight of the Year. Cotto and Margarito boast a combined record of 74-9 (56 KOs) – a winning percentage of 89% and a victory by knockout ratio of 76% -- not to mention seven world titles between them. Promoted by Top Rank, in association with Cotto Promotions, Tornado Promotions, AT&T, Tecate and Madison Square Garden, tickets to Cotto-Margarito II, priced at $600, $400, $300, $200, $100 and $50, including applicable service charges, will go on sale Today! Tuesday, September 20, at Noon ET. They can be purchased at the Madison Square Garden box office, online at www.thegarden.com and all Ticketmaster outlets. Ticketmaster charges an additional fee. "The first fight was a classic. I have a feeling that this fight will be much more intense, an outright war. -

Boxer Died from Injuries in Fight 73 Years Ago," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 28, 2010

SURVIVOR DD/MMM /YEA RESULT RD SURVIVOR AG CITY STATE/CTY/PROV COUNTRY WEIGHT SOURCE/REMARKS CHAMPIONSHIP PRO/ TYPE WHERE CAUSALITY/LEGAL R E AMATEUR/ Richard Teeling 14-May 1725 KO Job Dixon Covent Garden (Pest London England ND London Journal, July 3, 1725; (London) Parker's Penny Post, July 14, 1725; Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org), Richard Teeling, Pro Brain injury Ring Blows: Manslaughter Fields) killing: murder, 30th June, 1725. The Proceedings of the Old Bailey Ref: t17250630-26. Covent Garden was a major entertainment district in London. Both men were hackney coachmen. Dixon and another man, John Francis, had fought six or seven minutes. Francis tired, and quit. Dixon challenged anyone else. Teeling accepted. They briefly scuffled, and then Dixon fell and did not get up. He was carried home, where he died next day.The surgeon and apothecary opined that cause of death was either skull fracture or neck fracture. Teeling was convicted of manslaughter, and sentenced to branding. (Branding was on the thumb, with an "M" for murder. The idea was that a person could receive the benefit only once. Branding took place in the courtroom, Richard Pritchard 25-Nov 1725 KO 3 William Fenwick Moorfields London England ND Londonin front of Journal, spectators. February The practice12, 1726; did (London) not end Britishuntil the Journal, early nineteenth February 12,century.) 1726; Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org), Richard Pro Brain injury Ring Misadventure Pritchard, killing: murder, 2nd March, 1726. The Proceedings of the Old Bailey Ref: t17260302-96. The men decided to settle a quarrel with a prizefight. -

Oscar De La Hoya and Filmon TV Networks Create Two New Boxing Channels: the Ring and the Golden Boy Channel

Source : FilmOn.com 19 janv. 2016 17h40 HE Oscar De La Hoya and FilmOn TV Networks Create Two New Boxing Channels: The Ring and the Golden Boy Channel Rising stars streamed live and classic fights will reach FilmOn's 70 million monthly users around the world. First Livestream fights on The Ring will air Friday, January 29th BEVERLY HILLS, Calif., Jan. 19, 2016 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Two new boxing channels sure to draw fans of all eras of the sweet science are coming to the world's largest streaming TV service, FilmOn TV Networks, thanks to a new partnership announced today by Oscar De La Hoya, Chairman and CEO of Golden Boy Promotions, and FilmOn TV Networks CEO Alki David. Both channels will go live at the end of January and will be free as part of filmon.com's ad-supported OTT service. 10-time world champion De La Hoya's classic fights will air on the Golden Boy Channel, while Golden Boy Promotions' wildly popular monthly boxing series LA FIGHT CLUB will live stream its bi-weekly fights on The Ring, with the first kicking off at 5:30 PST on January 29th. "Past, present or future, Golden Boy Promotions has, is and always will be about pitting the best against the best," said Oscar De La Hoya, Chairman and CEO of Golden Boy Promotions. "This new partnership with FilmOn will only further showcase our mission by offering fans the best fights from today and yesterday." "Oscar De La Hoya is a universally beloved boxer who changed the sport forever," said Alki David, CEO of FilmOn TV Networks. -

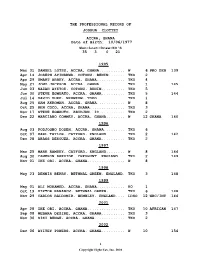

The Professional Record of Joshua Clottey

THE PROFESSIONAL RECORD OF JOSHUA CLOTTEY ACCRA, GHANA Date of Birth: 10/06/1977 Won-Lost-Draw-KO'S 35 3 0 21 1995 Mar 31 SAMUEL LOTSU, ACCRA, GHANA........... W 6 PRO DEB 139 Apr 14 JOSEPH AYINAKWA, COTONU, BENIN....... TKO 2 Apr 29 SMART ABBEY, ACCRA, GHANA............ TKO 4 May 27 JOMO JACKSON, ACCRA, GHANA........... TKO 1 145 Jun 03 NAZAH AYETOE, COTONU, BENIN.......... TKO 5 Jun 30 STEVE EGWUATO, ACCRA, GHANA.......... TKO 5 144 Jul 14 DAVID DUKE, NKOWKOW, TOGO............ TKO 1 Aug 25 SAM AKROMAH, ACCRA, GHANA............ W 8 Oct 25 REN COCO, ACCRA, GHANA............... TKO 3 Nov 17 STEVE EGWAUTO, ABIDJAN, IC........... TKO 2 Dec 22 MARCIANO COMMEY, ACCRA, GHANA........ W 12 GHANA 140 1996 Aug 03 PODJOGBO DOSEH, ACCRA, GHANA......... TKO 6 Oct 07 KARL TAYLOR, CATFORD, ENGLAND........ TKO 2 142 Dec 28 ABASS DESOUZA, ACCRA, GHANA.......... TKO 2 1997 Mar 25 MARK RAMSEY, CATFORD, ENGLAND........ W 8 144 Aug 30 CAMERON RAESIDE, CHESHUNT, ENGLAND... TKO 2 149 Nov 01 IKE OBI, ACCRA, GHANA................ W 8 1998 May 23 DENNIS BERRY, BETHNAL GREEN, ENGLAND. TKO 3 148 1999 May 01 ALI MOHAMED, ACCRA, GHANA............ KO 1 Oct 19 VIKTOR BARANOV, BETHNAL GREEN, TKO 6 148 Nov 29 CARLOS BALDOMIR, WEMBLEY, ENGLAND.... LDSQ 12 WBC/INT 144 2001 Apr 28 IKE OBI, ACCRA, GHANA................ TKO 10 AFRICAN 147 Sep 08 MEBARA DESIRE, ACCRA, GHANA.......... TKO 3 Nov 30 SIKI BENGE, ACCRA, GHANA............. TKO 2 2002 Dec 06 AYITEY POWERS, ACCRA, GHANA.......... W 10 154 1 Copyright Fight Fax, Inc. 2010 THE PROFESSIONAL RECORD OF JOSHUA CLOTTEY ACCRA, GHANA Date of Birth: 10/06/1977 Won-Lost-Draw-KO'S 35 3 0 21 2003 Nov 21 JEFFREY HILL, NY, NY................ -

World Boxing Council R a T I N G S

WORLD BOXING COUNCIL R A T I N G S RATINGS AS OF SEPTEMBER - 2016 / CLASIFICACIONES DEL MES DE SEPTIEMBRE - 2016 WORLD BOXING COUNCIL / CONSEJO MUNDIAL DE BOXEO COMITE DE CLASIFICACIONES / RATINGS COMMITTEE WBC Adress: Cuzco # 872, Col. Lindavista 07300 – México D.F., México Telephones: (525) 5119-5274 / 5119-5276 – Fax (525) 5119-5293 E-mail: [email protected] RATINGS RATINGS AS OF SEPTEMBER - 2016 / CLASIFICACIONES DEL MES DE SEPTIEMBRE - 2016 HEAVYWEIGHT (+200 - +90.71) CHAMPION: DEONTAY WILDER (US) EMERITUS CHAMPION: VITALI KLITSCHKO (UKRAINE) WON TITLE: January 17, 2015 LAST DEFENCE: July 16, 2016 LAST COMPULSORY: January 17, 2015 WBA CHAMPION: Tyson Fury (GB) IBF CHAMPION: Anthony Joshua (GB) WBO CHAMPION: Tyson Fury (GB) Contenders: WBC SILVER CHAMPION: Johann Duhaupas (France) WBC INT. CHAMPION: Dillian Whyte (Jamaica/GB) 1 Alexander Povetkin (Russia) * CBP * CLEAN BOXING PROGRAM 2 Bermane Stiverne (Haiti/Canada) 3 Kubrat Pulev (Bulgaria) EBU 4 Joseph Parker (New Zealand) OPBF 5 David Haye (GB) 6 Johann Duhaupas (France) SILVER 7 Andy Ruiz (Mexico) NABF 8 Bryant Jennings (US) 9 Malik Scott (US) 10 Eric Molina (US) 11 Gerald Washington (US) 12 Carlos Takam (Cameroon) 13 Mariusz Wach (Poland) 14 Dereck Chisora (GB) 15 Jarrell Miller (US) 16 Kyotaro Fujimoto (Japan) 17 Andrzej Wawrzyk (Poland) 18 David Price (GB) 19 Chris Arreola (US) 20 Alexander Dimitrenko (Russia) 21 Dillian Whyte (Jamaica/GB) INTL 22 Dominic Breazeale (US) 23 Andriy Rudenko (Ukraine) INTL Silver 24 Charles Martin (US) 25 Oscar Rivas (Colombia/Canada) 26 Francesco