NHSLothian Strategic Plan and 2020 Vision: Primary Care requirements to make it work

Our ‘2020 Vision’

“Our vision is that by 2020 everyone is able to live longer healthier lives at home, or in a homely setting.

We will have a healthcare system where we have integrated health and social care, a focus on prevention, anticipation and supported self-management. When hospital treatment is required, and cannot be provided in a community setting, day case treatment will be the norm. Whatever the setting, care will be provided to the highest standards of quality and safety, with the person at the centre of all decisions. There will be a focus on ensuring that people get back into their home or community environment as soon as appropriate, with minimal risk of re-admission”. Scottish Government

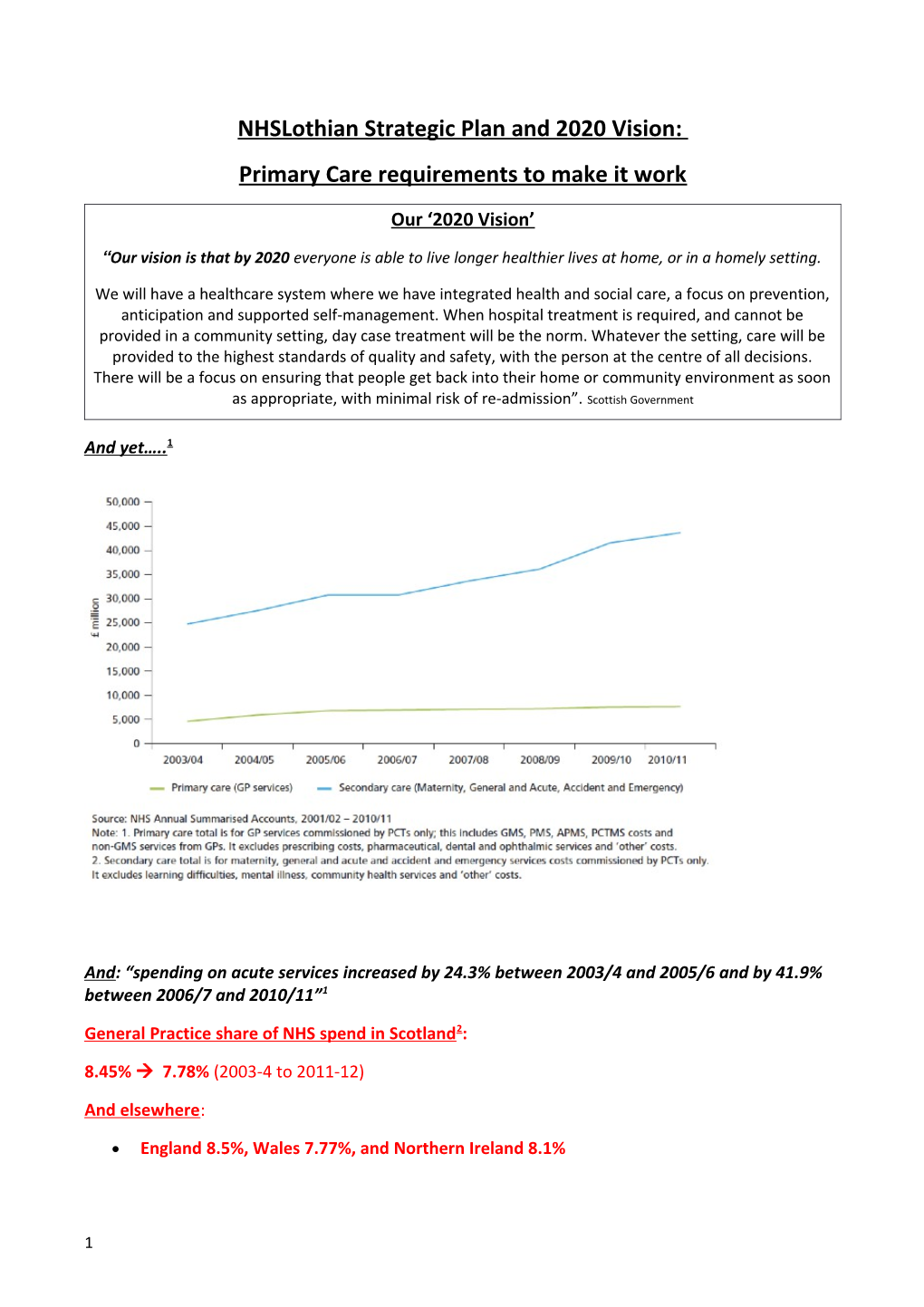

And yet….. 1

And: “spending on acute services increased by 24.3% between 2003/4 and 2005/6 and by 41.9% between 2006/7 and 2010/11”1

General Practice share of NHS spend in Scotland 2:

8.45% 7.78% (2003-4 to 2011-12)

And elsewhere:

England 8.5%, Wales 7.77%, and Northern Ireland 8.1%

1 UK overall: 8.4% Objectives for primary care

Emergency measures for rapid expansion of General Practice in view of the current severe lack of capacity and destabilisation;

Establish infrastructure to support 2020Vision, which will require amongst other developments, and as a minimum: 10% more GPs; 10 more practices; increase in the GP share of NHS funding to the 11% recommended by the RCGP, more community nurses and other support staff; single point of contact available 8am to 7pm Monday to Friday for admissions avoidance (including transport arrangements); expansion of enhanced service funding, including those to support increased community based medical care of vulnerable and multi-morbid patients (General Practice ‘Intensive Care Units’); resource weighting to at least cover the additional workload associated with deprivation; improved IT;

Resourcing LUCS in line with its workload and supporting development of innovative schemes to support out-of-hours working;

Improve integration with H&SC Partnerships;

Improve joint working with secondary care, including at locality level;

Develop a new workforce to undertake current secondary care work in the community and absorb that associated with new ways of outpatient working;

Maximise quality and efficiency by fully supporting GP clinical leadership roles in prescribing, referrals and admissions management & clinical investigation workstreams. Some of this work should help facilitate disinvestment. Implementation: 20 requirements for 2020 Vision

This is a summary with fuller detail in the appendices. Some of this DOES appear in the Strategic Plan, particularly the appendices, but is acknowledged here too.

1. 2020 Vision requires - above all - more GP hours in Lothian. GPs are already working in the way outlined by the strategic plan – expert generalists at: efficiency (and already far down that curve…) rapid diagnosis, risk assessment, managing uncertainty, team working (with a central ‘directing’ and hub role and crucially maintaining long-term relationships and stability), using community facilities, integrated care, prescribing, LTCs, palliative care, record keeping, IT, patient knowledge, holistic care, communication skills, teaching, training and public health implementation. For £70.00 per patient per year, GPs provide high quality records, prescriptions, unlimited consultations, house calls, nurse time and telephone calls, at a fraction of the cost of a single outpatient appointment3. Extensive American- based reviews suggest that an increase of one GP per 10,000 population is associated with an average reduction of 49 fewer deaths per 10,000 p.a.1 Mental health is another area where GPs are the key deliverers of care - and this, above all, requires adequate and therapeutic GP time and space. Increasing evidence supports psychological therapies, and yet there remains a chronic under-provision of formal mental health services. That ‘there is no health without mental health’ is supported by the evidence: we know that co-morbidity is a huge determinant of mortality and morbidity (including admissions – see 15) and there are few pharmacological or technological short cuts to aiding recovery.

GPs are core to managing complexity and multi-morbidity in the community and 2020 Vision will not work without more of them. LUCS is dependent on having a big enough pool of experienced, motivated,

2 and non-exhausted GPs for its work and this is currently compromised. We already work on the right hand side of the table, but are being driven to the left by lack of resource, cut-backs, workload and fragmentation. 10% of the population consults with us weekly, an astonishing level of access, surely the highest in the world?

To an extent the challenge is process (Hannah and her ‘colleagues’ should help with that), but mainly volume and interface working – both will need to expand considerably. NHS Scotland’s route map to 2020 Vision4 makes it clear that there is an “urgent need for an expanded role for primary care and general practice in particular…is at the heart of 2020 Vision…and represents a critical prerequisite to tackling health inequalities and the challenges facing unscheduled care…”.

2. The Workforce Demographic. The evidence in the UK is: more part time working (especially younger GPs), early retirement; emigration; fewer entering General Practice; and female GPs in particular leaving the profession at a young age. Every GP costs the taxpayer half a million pounds to train. Nationally six out of ten GPs intend to retire early (particularly worrying as 40% of GPs are over 50, 22% over 553), GP training applications are 15% down in the last year and there has been no dedicated funding for new premises for over a decade. NHSL has to account for the new demographic when it considers and implements policies, particularly as the 2013 Primary Care Workforce Survey (ISD) showed that non- partners and younger GPs tended to have lower sessional commitments. In a recent South-East of Scotland survey of GP trainees (see below) only half were considering partnership in the long-term (at 10 years). NHSL has sometimes restricted measures which retain GPs – (wrongly) reducing funded Retainer sessions from 4 to 3; less generous maternity/paternity provision than almost all other Health Boards and so on. Dr Amy Small’s survey of final year GP Registrars (2014) saw a return of 31 questionnaires (62% response rate). Their expressed ambitions were:

In the next year: 8 salaried, 2 partners, 2 retainers, 28 locum;

In the next 2 years: 20 salaried, 6 partners and 1 retainer;

In the next 10 years: 4 as salaried, 15 as partners and 4 unsure;

Out of Hours work: 22 are considering, 4 definitely not and 4 unsure;

No-one planned to still be undertaking locum work in 5 years.

The view of Professor Anthea Lints (NES) is that: “Lothian, Fife & Borders fills most of its training places through the annual recruitment cycle, though in recent years there have been significant numbers of unfilled vacancies elsewhere in Scotland, particularly in the north and west. This year (2014) there were 33 unfilled GPST programmes in Scotland after recruitment was complete compared to 25 unfilled programmes in 2013. However nationally there were slightly fewer applicants for GPST programmes overall but significantly fewer (-558) applying from UK Foundation Programmes.

Increasing recruitment would not provide an immediate solution to increase the trained GP workforce. More effort needs to be made to encourage retention and re-entry. The retainer scheme continues to thrive in Lothian through support from the Health Board however lack of protected funding has hindered a more proactive approach to support post-CCT doctors returning after a career break or those who are included on the GMC GP Register but with no experience of working in the NHS. Induction and returner programmes are available locally but funding is uncertain and unreliable. Scottish Government, Health Boards and the Scotland Deanery are considering how funding could be managed sustainably and how these programmes could then be advertised more actively.

Similar strategies are being discussed in England. Returner programmes in England are educationally similar to those proposed in Scotland although entry criteria and assessments are slightly different. Assuming an

3 increased supply of "inducted" trained doctors from strategies on both sides of the border, Scottish practices who need trained GPs could offer attractive opportunities within a competitive UK market (such as flexible working hours, protected time to engage with local PBSGL groups or attend CPD events, opportunities to develop special interests within and outside practice, involvement in local health planning and in local partnerships, better conditions through working with NHS in Scotland, study leave and funding, mentoring arrangements)” 3. GP Sustainability. This is integral to maintaining the workforce. Lothian now has to do everything it can to make Lothian a good place to work on all fronts – to maintain our GP headcount we have to compete to be more attractive than elsewhere, including to retainers, returners and the newly-qualified, and advertise those advantages to the world. The strategy needs to state explicitly that we need to make working in Lothian appealing to GPs, and support GP functions in order to do this. This is on a background of Scottish GP contractors earning almost £20 000 p.a. less than their English counterparts and considerably less than their Welsh and Northern Irish colleagues. However, Lothian does offer benefits: a high quality medical environment both in primary and secondary care; the Scottish - rather than English - infrastructure and approach, including none of the CCG, CQC, private primary care provision and other difficulties of the NHS down south, and a helpful and interactive PCCO. NHS Lothian is currently unique in Scotland in continuing to offer comprehensive Occupational Health provision to practices: we have just been informed of the withdrawal of this service, which is not helpful in terms of enhancing recruitment. Yet all these mean very little if the daily workload of a GP is overwhelming and increasingly impossible, with ongoing erosion of any semblance of an adequate work-life balance. We need to reverse the downward spiral of morale and promote a positive vision of General Practice within Lothian and the press, develop better premises, good relationships and improved working with secondary care. We know from healthcare evidence that the locus of control is critical to individual wellbeing, another reason to establish new mechanisms for agreeing, and managing, the current unresourced secondary care workload (which GPs find very dispiriting), as well as that associated with 2020 Vision.

4. 10 new practice premises with funding for all the practice expansion/development identified by the LEGUP (List Extension Growth Uplift) consultation and in the Premises Paper (Edinburgh ). An equivalent is now required for the other areas of Lothian, where greater populations expansions than Edinburgh are anticipated. In 2010-2020 it is predicted that the over- 65s will increase by between a quarter and a third in each of West-, Mid- and East-Lothian. LEGUP brings inequity (non-LEGUP practices under huge pressure are registering new patients without added resource) and risk to practices (if they cannot maintain patient numbers), but is arguably efficient – allowing practices to essentially expand with a minimal additional spend. This has ‘natural limits’ and the Board should be attempting to maximise - rather than restrict - LEGUP payments to make use of this mechanism whilst it remains feasible. Its lifespan is pretty short as there is a ceiling to GP efficiencies and practices are finding it increasingly difficult to recruit staff. Primary care builds, including new practices, need to be better defined in the Plan – in line with secondary care ones- or we fear that they won’t take place. Our view is that many of the secondary care spends outlined in the Strategic Plan are not affordable - page 46 of the Strategic Plan states: “The large funding gap in the years 2016-2019 is due to large capital schemes”.

5. New secondary care nurses and HCAs in the community to perform bloods, ECGs, BPs, surgical wound care and so on delegated to GPs by hospitals. Currently GPs undertake 100-150 chemotherapy bloods daily, thousands of PSAs and many other tasks requested by secondary care: 4,000+ pre-op MRSA swabs are required in Lothian for cataract surgery alone (GPs already do some unresourced) and many could be done closer to home, reducing hospital-based care. Such work currently has a DOUBLE cost for GPs – who have to organise the test itself, but often also inform secondary care of the result, or check that it is being managed. (NB: There are very significant clinical governance issues relating to this too - particularly round PSAs). This workforce may also be needed to undertake DMARD work if that is not fully funded in the enhanced service. We need an agreed Charter of joint working, which should also

4 improve quality, reduce risk and enhance working relationships. We now reluctantly accept that we have to contemplate a deadline after which GPs will no longer undertake tests for secondary care, in order to maintain clinical safety. Such an agreement will also be required to progress work round any data sharing, and the Clinical Portal.

6. A six month rapid needs appraisal. Practices (& the PCCO) can readily submit: ACPs, patients over 65, 75, 85, patients on palliative care register, housebound, care homes, health inequalities and so on. Some of this work is already underway and partly as a QOF Quality Improvement Data set.

7. New community staff: We need to establish safe levels of community staffing for a defined and expanding workload. This should include new community palliative care nurses on the basis of thousand patients over 65; new practice-attached community nurses per thousand over 75 (>65 for practices with 35% of patients in SMD 1stquintile, reflecting the evidence base) to undertake holistic multidisciplinary care with chronic disease support. This is crucial for improved Support for Self-Management (SSM). The ‘Primary Care Strategy Demand, Capacity and Access’ appendix clearly outlines the pressures of the increasing population and that community nurse provision has FALLEN in relation to this, and this fall is even more severe as patient complexity has increased and there is a documented rise in deaths at home (terminal care is extremely costly in District Nurse time). More community nurses will be needed for the rises in dementia (70% in the next 20 years), multi-morbidity (associated with the 22% increase in >75 by 2020) and cancer (20.5% increase estimated in Lothian by 2020). Also needed is community nurse support for care homes (and perhaps other work too) to act as first point of contact for problems, including those presenting out-of-hours, in order to safeguard GP capacity. We also need more HVs, particularly in view of the impractical and unnecessary ‘named person’ scheme, and more community midwives, especially in areas of deprivation.

8. Care Home Standard Operating Procedure. Drs Carl Bickler and Nigel Williams have offered to do this.

9. Out of Hours. LUCS needs significantly more GPs to be sustainable, very much mirroring the in-hours requirements. See appendix 3 (Dr Sian Tucker).

10. Full funding of enhanced services – our principal current mechanism for significant resource transfer. We have currently limited, or no, funding for DMARDs, vLARC and the new Diabetes ES proposal. We need assurance of further resource subsequently – tackling diabetes in the middle years was identified by the Strategy as an effective intervention, but remains unfunded. We need realistic resource for the ES for elderly-frail-multimorbidity-housebound and Care home work. The second of the Government’s ‘triple aims’ is to improve the health of the population and the Committee has already objected to the anticipated withdrawal of the Alcohol enhanced service. Of note, too, is that we have some excellent innovators in Lothian, who provide potential models for new work, including round dementia and health inequalities (eg. Dr Patricia Donald’s 17c work; David White’s Headroom Project).

11. Integration has to change how we work but we still lack the evidence base for money saved: the early analysis is that it does change approaches to patient care but does not necessarily reduce costs5. The

5 much-quoted Nairn model did not save money but did move patients from secondary to primary care and provides an evidence base and mechanism for this6.

12. Primary-secondary care working. There is extensive room for improvement and expansion. There have been multiple secondary care-led attempts to rationalise referrals in particular. The King’s Fund has clearly outlined that systems change will not be effective using this model, and requires instead the active participation of all those involved. The 2011 Audit Scotland national Review of Community Health Partnerships7 advocated change, noting that GPs indirectly commit significant NHS resources, but are not fully involved in decisions about how resources are used. ‘Teams without Walls’8 the joint RCGP, RCP and RC Paediatrics & Child Health document also outlines the benefits of joint approaches to services planning. Entirely new systems workstreams with resourced GPs at their centre will be needed to take this work forward. (See appendix 2).

13. IT. This has generally transformed our work for the better, but is also slow and often poor. GPs have identified packages and systems which would help both clinical and backroom functions in terms of time and efficiency savings but are told funding is not available for these. Investment would free up some capacity – particularly ‘backroom’ - and be much more efficient than alternative proposals round systems sharing. The GP Sub-Committee is about to review data sharing arrangements and continues to collaborate positively with the Integrated Resource Framework and SPIRE. Every Care Home needs a terminal with web access to allow GPs, DNs and LUCS to use Vision 360 and the Clinical Portal and this should be part of the Care Home SOP.

14. Prescribing. The LJF is an extremely cost-effective resource – and GPs have saved huge amounts of money through its use and judicious prescribing. These efficiencies need to be fully implemented in secondary care and every effort made to maintain and develop the LJF itself. Not including premises, prescribing is the 2nd biggest NHS cost after staff (£132million p.a. in Lothian primary care). In order to save money we need a routine Community Pharmacy presence in practices. See Appendix 2.

15. Laboratory tests. There is a proven track record in Lothian of a joint primary-secondary care group (PLIG) saving NHSL substantial money over the years through reductions and rationalisation of laboratory testing. This group has also improved quality and safety round test ordering and understanding, so crucial to good clinical management. ALL its guidance is produced with an evidence base, agreement between primary care, secondary care clinicians and senior laboratory staff and approved by the GP Sub- Committee. There is considerable capacity for further savings – in terms of rationalising tests (saves GP workload too in terms of processing results) and introducing new tests which potentially save referrals and admissions. The laboratories are keen to do more, but unfortunately it has not been possible to fund a post of a GP session a week to take forward this important work which would save money, support quality, facilitate transfer of work from secondary to primary care. Three years on, we still do not have funding for BNP, a test which NICE claims substantial cost savings as it allows primary care to readily exclude heart failure without a referral for a cardiac echo, and may prevent admissions. This does not auger well for effective change more generally.

16. Health Inequalities. NHSL does not resource this work to any meaningful scale in primary care – and yet poorer populations generate a very disproportionate morbidity and workload for both practices and

6 secondary care. The Audit Scotland report, ‘Health Inequalities in Scotland’9outlined that there were some improvements but:

the health inequalities due to deprivation (the biggest driver) remain and are significant

healthy life expectancy has not improved (18 years between worst and best): the Strategic Plan itself states that that people living in the most affluent communities in Lothian can expect to live 21 years longer than people living in the most deprived communities)

the life expectancy gap for women is increasing (7.5 years between worst and best; the equivalent for men is 11 years);

average life expectancy in Scotland is lower than the UK averages (and most of Western Europe) for both men and women.

The report states that “Primary care is the main focus of most efforts to reduce health inequalities”, and refers to the Equally Well advice that: “NHS action to reduce health inequalities starts with primary care, where more than 90% of patient contacts take place”. It is not clear to us (or to the Audit Scotland) where the £170million (2011-12) allocated to Boards for this work was spent, nor that there has been implementation of the report’s recommendations for Boards to “review the distribution of primary care services to ensure that needs associated with higher levels of deprivation are adequately resourced”.

We know that highly deprived practices contribute disproportionately to admissions and referrals. Using Scottish data, in a large retrospective cohort study, Payne et al10 demonstrated that 20% of adult patients with ≥4 physical health conditions had at least one unplanned hospital admission during the study year. Socioeconomic deprivation was an independent risk factor for this, doubling rates of both unplanned and ‘potentially preventable unplanned’ admissions (using the standard NHS Scotland definitions for the latter) between the most - and least - deprived quintiles. Mental health co-morbidity increased the risk yet further and those with both accounted for almost half of all potentially preventable unplanned admissions. Those patients suffering the triple whammy of multimorbidity, mental ill-health and being in the most deprived quintile had 51 times the odds of a potentially preventable unplanned admission. The trends in Lothian are equally clear and referred to in the Strategic Plan:

Our excellent practice level deprivation data potentially provides a highly effective avenue for targeting resource on a need- and evidence- basis, and it would be entirely feasible to construct an enhanced service for the practices serving the most deprived populations. Stewart Mercer is able to provide

7 further evidence of the cost-effectiveness of practice-based targeted ‘Care Plus’ interventions. The Headroom Project may give some pointers for change, or the 17C pilot focussed on families and based on GPs at the Deep End proposals. However the inequalities gap is widening, is likely to be made worse by austerity (yet another source of increased GP workload11) and the draft Health Inequalities Strategy does not address this either. The ‘GPs at the Deep End’ group notes that there are 11% more WTE GPs in the more affluent, than more deprived, half of the population. It has produced a prototype Enhanced Service for highly deprived practices (summarised in the Strategic Plan’s second appendix) following 5 years of deliberations of the evidence12. We recommend this is implemented in the 9 practices in Lothian whose population in the top SMD quintile exceeds 40%.

17. Expectations . The public needs to know that the NHS has to rely on them increasingly to deal with the ‘little things’ so that it can deliver the ‘big things’. This requires that the public be informed at a national and Lothian level – and not only by their GP – that if they have a minor condition or need advice, or want a particular form of treatment which is at the ‘want’ rather than ‘need’ end of the spectrum they may not get it. And we do NOT universally need - nor should expect to get -a GP routine appointment in 48 hours (or at all for some things). We all have to be willing to accept brief advice, and understand that there is now LIMITED GP RESOURCE which needs to focus on the ill, vulnerable and dying, and public health priorities.

There needs to be a radical shift in the expectations of institutions too, including employers. GPs find it very difficult to make a patient living in poverty on a minimum wage pay for a private sick line requested by their employer, but the true cost is an unnecessary GP consultation and a demeaning of the patient. Employers, Councils (and hospitals!) need to be aware that every time they ask for an unjustified fit note or letter, they are essentially depriving another patient in need of an appointment (and payment for such work is irrelevant where there are not the GPs to do it). The Scottish Government also has to: 1. Stop campaigns without a public health evidence base that increase workload without proven benefits. 2. Not make promises about healthcare without fully discussing capacity and their wisdom with the medical profession first (including General Practice and Public Health). 3. Take a lead with its population in understanding that the NHS is there for need not want – whilst keeping healthcare services empathic and supportive. Some of the most effective disinvestments have been nationally-led, eg that benign skin lesions with no other medical significance will not be removed or the fall in service requirements as a result of the ban on smoking in enclosed public places.

Supported Self-Management (SSM) needs to be publicised nationally for its role in chronic disease care – over 2 million Scots live with long term conditions, the 30% of the population which accounts for 70% of the spend1. There is more that can be done round prescribing, too, facilitated by a shift from a demand- led service. Polypharmacy reviews offer an effective way of stopping treatments in the elderly with appropriate evidence and basis for discussion13- but again are time-consuming (GP time) and require a change in public awareness, including of the limits to medicine.

Both NHSL and the Scottish Government need to be much more brave and transparent about taking this forward. We should all support the Board in an open approach with Scottish Government – that we can no longer promise to deliver further transfers of care into the community without paying heed to the RCGP call for more resource including the 50:50 balance of hospital/GP training posts, and implementation of the College’s recommendation that General Practice receive 11% of the NHS budget. To save the NHS we need governments to accept that it is there to provide the best possible care to the many, not the few, within the confines of a fixed resource.

18. Intermediate Care. We have supported moves to extend ‘Step Down’ and similar initiatives, but NHS Lothian may have under-invested in other forms of intermediate care. The Faculty of Sport and Exercise Medicine (UK) is an intercollegiate faculty the Royal Colleges of Surgeons (Edinburgh) and Physicians

8 (London). Their 2014 NHS Information Document gives commissioning advice14. Various MSK projects are described which have resulted in reductions in orthopaedic referrals by a quarter to a half, a substantial increase in ‘efficiency’ in orthopaedic outpatient surgical conversion rates (in some cases to almost 100%), reduction in scanning costs and physiotherapy waiting times, and high patient satisfaction rates. Such services also support General Practice where MSK conditions can account for upto 30% of primary care consultations. Tayside has used this approach in an integrated MSK service. Lothian has two musculoskeletal clinics but has not rolled out this approach further. However GPs with a Special Interest in some other settings have not been thought to necessarily save costs1.

19. What can we stop? Disinvestment - see appendix 2.

20. We need a new universal approach: that the right thing to do is made the path of least resistance for everyone:

Easier for a GP to arrange a package of care to keep a patient at home - than admit…(even at 6pm on a Friday night…)

Easier for all doctors to prescribe an LJF-recommended drug for a particular indication - than any other…

Easier for secondary care to arrange for a community blood test – than get a GP to do it…

Easier to e-mail a specialty or speak to a consultant - than refer a patient unnecessarily…

Easier for a patient to speak to a member of the practice clinical team when indicated – than turn up at A&E…

Easier to get a patient seen by a hospital team in daytime hours – than admit overnight due to delayed transport …

Easier to prescribe exercise - than a tablet…

Easier to refer to the third sector – than give an antidepressant…

Easier to give a leaflet on inappropriate antibiotics – in the top five most common languages spoken in Lothian – than prescribe for a sore throat…

Easier for a community nurse to refer directly to podiatry – than to a GP to do…

Easier to do an electronic X-ray referral – than a paper one…

References.

1. RCGP: Patients, Doctors and the NHS in 2022 – Compendium of Evidence.

2. ‘Under Pressure: The Funding of patient care in General Practice’. Deloitte, commissioned by the RCGP. April 2014.

3. British Medical Association figures 2014, quoted by Dr Chaand Nagpaul, Chair, General Practitioners Committee.

9 4. ‘A Route Map to the 2020 Vision for Health and Social Care’ NHS Scotland.

5. Financial benefits of integration: a case of wishful thinking? Vize, Richard. BMJ 2014; 348:g3661.

6. Anticipatory Care Planning and Integration: A primary care pilot study aimed at reducing unplanned hospitalisation. Baker et al, Brit J. of GP Feb 2012.

7. Review of Community Health Partnerships. Audit Scotland. June 2011.

8. ‘Teams without Walls. The value of medical innovation and leadership’. 2008. Report of a Working Party of the Royal College of Physicians, the Royal College of General Practitioners and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health.

9. ‘Health Inequalities in Scotland’. Audit Scotland December 2012.

10. ‘The effect of physical multimorbidity, mental health conditions and socioeconomic deprivation on unplanned admissions to hospital: a retrospective cohort study. Pane et al, CMAJ 2013.

11. ‘GPs’ workload climbs as government austerity agenda bites. G Lacobucci. BMJ 2014;349:g4300 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4300 (Published 2 July 2014)

12. ‘What can NHS Scotland do to prevent and reduce Health Inequalities? Proposals from GPs at the Deep End’. March 2013. 13. ‘Polypharmacy Guidance October 2012’; NHS Scotland. Developed by The Model of Care Polypharmacy Working Group; Quality and Efficiency Support Team; Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates. 14. ‘Sport and Exercise Medicine’. A Fresh Approach in Practice. A NHS Information Document. (Faculty of Sport and Exercise Medicine UK), 2014.

10 Appendix One: General Practice - national and local overview

The National Picture.

General Practice offers the NHS huge advantages. It provides global cover, personalised, high quality care, is extremely cost effective and is equitable. Nineteen of every twenty contacts with GPs are also concluded in General Practice. GPs are able to manage demand, partly as they know their patients well and have access to their lifelong records, but also as they are skilled in rapid assessment, risk management and dealing with uncertainty. Every day sixteen times more people attend their GP Surgery than A&E, and the number of GP consultations per annum has increased by forty million in the last five years1: GPs have seen a greater rise in workload than any other sector. Yet this has been accompanied by a fall in funding nationally, with a £450 million reduction in the last three years: Scottish and Welsh GPS fare worst in terms of the % allocation of the NHS budget. It is increasingly recognised that General Practice is facing a ‘perfect storm’ crisis of rising work load, a reducing workforce, inadequate premises and the lowest GP morale of a decade. GPs have been treated with hostility in the press, with little acknowledgement of their role as highly committed, overworked public servants - whose suicide rate remains twice that of the general population.

2020 Vision aims to bring patients back into the community, but increasingly the ten minute consultation - always pressured - is completely insufficient for dealing with expectation and multimorbidity. The pioneering work done in Scotland initially by Professor Howie and more recently by Professors Phil Cotton and Stewart Mercer (with their emphasis on the longer ‘CARE’ consultation, empathy and self-management) gives an evidence base for the value of longer appointments, which remain beyond reach for almost all. ‘Co-creation’ of health using SSM techniques requires longer appointments, although these are more productive and significantly reduce the secondary care footprint2. Yet GPs can see over forty patients a day in some practices: in England this is rising to sixty. And what has expanded in tandem is telephone calls, house calls, repeat prescribing and multidisciplinary work. Currently 340 million patients see their GPs each year, compared with 21 million in A&E - itself under pressure. A mere 6 % transfer of consultations from General Practice to A&E is estimated to double A&E attendances1. This must be a risk in Lothian as practices close to new registrations.

New approaches to General Practice are being considered, but we know from international comparisons, well described by the late Barbara Starfield (John Hopkins) that the crucial spend in terms of improving health outcomes is on effective personalised longitudinal care. Tele-health does bring advantages, as does new internet-based programmes, but the 2010 ONS survey demonstrated that 60% of UK adults over 65 had never used the internet, and technology can widen health inequalities for those with poor health literacy (who already have poorer health status and undergo more hospital admissions)3. Telephone triage approaches have also been advocated by some: 12% of GP consultations are already telephone ones, and a recent RCT has assessed systematic telephone triage approaches4. The results showed a marked reduction in face-to face consultations with a GP but there was an overall statistically significant increase in GP workload due to an increased mean numbers of GP telephone consultations per patient by ten times in the triage groups (and a slight increase in face-to-face consultations with a nurse). Costs were not reduced. However the authors suggested that there was likely to be a continued role for such approaches and recommended further research as their trial was not able to determine outcomes round safety or effect on attendances elsewhere. Some in Lothian have found the ‘Patient Access’ approach useful whereby all patients receive a phonecall from the GP, but early reports (PCFG Feb 2013) were that this changed which patients were seen (and how), but did not reduce the overall requirement for GPs. A recent RCGP article has also outlined that patient access is a complex issue and that there is no single intervention which will ‘solve’ the problem 5.

GPs are core to the solution, and this is well acknowledged in the Strategic Plan. The NHS puts not only secondary care services, but its very existence at risk, if it ignores the prospect of severely limited - or no - GP access. Yet there is scant detail in the Plan of the funding required to maintain GP services.

11 Premises.

The BMA has published its findings from a premises survey (England and Scotland, released August 2014). The findings were that:

Almost two-fifths of all responding practices do not consider their current premises adequate for the provision of basic general practice service, and almost seven in ten feel their premises restrict their ability to offer additional or enhanced services

Over one-third do not have sufficient space to provide GP training

Over half feel their premises restrict patient access to primary care, preventing them from offering an adequate range of appointments

Almost four in five are unable to host a full primary care team (district nurses, health visitors, midwives etc) due to lack of space

Over half have not seen any significant refurbishment or development to their premises in the past 10 years

Over three in five have been prevented from undertaking any refurbishment or development due to lack of funding

More than half either do not believe (41 per cent) or are not sure (13 per cent) that they can expand to meet current or future needs

Six out of ten practices feel unable to relocate to new premises due to funding constraints.

“Six in 10 in Scotland say they believe ‘hot-desking’ or sharing consulting rooms is restricting the number of appointments their practices can provide. GPs are concerned it damages the overall delivery of services” – a higher percentage than in England, and a significant threat to the viability of 2020 Vision. Of note, was that nearly one in two practices state that their premises could be suitably adapted or extended to provide greater capacity for their patients' needs and the BMA considered this a very cost-effective investment.

The Lothian Picture

Premises.

The Premises annex of the Strategic Plan outlines that “across Lothian, 38 practices have been identified as requiring premises solutions to current capacity, compliance or quality issues and to address the future population growth”. This represents around a third of Lothian practices.

NHS Lothian now has a huge Primary Care deficit to make up: in ten years there was not a single new GP Practice despite massive increases in population and medical complexity. NHSLothian has paid for an entirely new Royal Infirmary (£183million using the costly and inefficient PFI funding mechanism), a new Birth Centre (£2.8 million), with explicit plans for a new Cancer Centre, Hospital for Sick Children and new Psychiatry Hospital. There have been some new GP builds, but to re-house existing practices which were in premises essentially not fit for purpose. The ‘Population and Premises Plan’ is to be welcomed – particularly as the original stance of no new practices has been dropped subsequently (Note though that the updated recommendations do not appear in the Strategic Plan appendix). This will still be inadequate, and does not extend outwith Edinburgh, where some of the biggest population rises are anticipated. It has taken 18 months to agree to a minimal capital spend of £200,000 for minor upgrades and this has still not been implemented – and yet likely represents one of the best value-for-money interventions NHSL could make: the rationing approach to Primary Care funding remains regressive.

12 Workforce.

The Health Board may decide to spend more on General Practice, but there may not be the GPs to fill these places. The current chronic and acute stresses on General Practice mean that even the most resilient and committed of GPs are now considering leaving, simply as the notion that it is worthwhile being a personal doctor to someone in need is being destroyed by the pressure of unremitting and unaddressed demand. If we have reached a position of irreversible GP decline, the Health Board will need to consider alternative facilities for managing patients who are unable to register with a practice. This inevitably will increase the secondary care footprint as the evidence around general practice, which is now extensive, is that not only do GPs manage complexity and morbidity very well, but that continuity of care reduces admissions 11.

NHS Lothian now has the poorest record of practices unable to register new patients in the whole of Scotland, a legacy of its underinvestment in primary care. There are large parts of Edinburgh, where patients cannot register locally, and anecdotally have to try up to three practices before they find one prepared to accept them. NHS Lothian needs to consider telling its population that GP practices are not readily accessible for some, so that practice teams are not penalised further by having to manage the understandable upset following this.

Since 2000, GP list sizes in Edinburgh have grown by 35,596 patients. Only a third of this growth was facilitated by new builds and these were new premises for existing practices, rather than new ones. The remaining 24,000 people have been absorbed by practices increasing their list sizes. A worry must be that very large list sizes lead to reduced patient continuity of care. With the expansion of complex care of the elderly and, in particular, palliative care in the community, there is a risk that moving to inappropriately large practices may bring hazards in terms of GP retention and continuity of care for patients.

Scotland has not embraced the ‘mega-practice’ approach of some in England, but rather retained its partner-rich practices which some argue bring more stability and long-term commitment. International comparisons show that primary care models with large numbers of salaried GPs lacking ‘ownership’ of practices, partnership or work, tend to eventually lead to a demoralised, low quality service. English GPs are exiting in their droves, and unfortunately we are beginning to see this in Scotland too.

In June 2014:

19 practices in Lothian had declared themselves ‘open but full’, ie unable to take on new registrations;

A further 3 would only accept ten new patients per week, which is so minimal as to be the equivalent;

Another 10 have restrictions on registrations, some fairly severe;

This essentially means that around a quarter of Lothian practices either will not register, or accept very restricted numbers of, new patients;

Inevitably, this has knock-on effects for neighbouring practices, simultaneously widening and deepening the area of crisis.

This calamity is unprecedented in Lothian. Just £200,000 is to be shared amongst 8 Edinburgh practices (with a further £25,000 for one mid-Lothian practice) to increase their list sizes, less than the cost of a small Edinburgh flat. Initial discussions were run on a high-trust, high-transparency co-operative model: 32 Edinburgh practices expressed an interest in LEGUP, but instead of maximising every opportunity to invest, particularly as its viability is short-lived, the LEGUP funds have been capped and the vast majority of interested practices rejected. Some of these remain in dire straits. Although we have major reservations

13 about LEGUP money, it is worrying that in the face of a primary care evolving disaster, limited amounts of money should be further restricted.

Finally, the GP out-of-hours service finds itself in an equivalent situation, and also requires a marked increase in GP hours for it to remain viable. The continued tendency in planning discussions is to consider the GP footprint in secondary care, but the focus increasingly needs to be on the sheer survival of primary care itself. There are practices in the UK which are now considering closing permanently, as the partnership believes that it is simply no longer worth it. Again, using international comparisons, it is very difficult to establish a primary care service anew, and we need to ensure that we do not lose - at any cost - the one that we have.

References.

1. British Medical Association figures 2014, quoted by Dr Chaand Nagpaul, Chair, General Practitioners Committee.

2. Care Planning. Improving the Lives of People with Long Term Conditions. Nigel Mathers et al. Clinical Innovation and Research Centre 2011 (RCGP publication).

3. ‘Engaging Patients in Healthcare’; Angela Coulter; 2011.

4. Telephone triage for management of same-day consultation requests in general practice (the ESTEEM trial): a cluster-randomised controlled trial and cost-consequence analysis. Campbell et al. The Lancet 10.1016/50140-6736 (14) 61058-8. August 4, 2014.

5. ‘Telephone Triage in-hours: does it work?’ Stephen Gillam. Editorial, British Journal of GP; July 2014, 327-8.

6.

14 Appendix two – Disinvestment and Primary-Secondary Care Working.

What can we stop? – disinvestment.

1. No further secondary care builds– instead insist that hospitals adopt the historical (and largely continued) approach of primary care, which is to adapt existing buildings. Savings would fund the entire primary care resource shift and the required £40m p.a. savings. Builds could be anticipated once Lothian funding increases again.

2. Shift secondary care tasks to a new workforce. This could save secondary as well as primary care work: the RIE Lipid Clinic has done extensive work on this and can significantly reduce face to face appointments if the patient could have a blood test and BP check done elsewhere (see Appendix 4). Clearly it is inappropriate for GPs to take this on but it does justify new secondary care nurse/HCA staff in the community. The lack of this provision is essentially blocking progress in several out-patient programmes, including a virtual Inflammatory Bowel Disease clinic. A clinic appointment costs around £180 but as Lothian has the 4th highest DNA rate in Scotland (10% in Nov 2012), the real cost is presumably higher?

3. Refhelp and referrals management: ‘ Minding the gap’. The National Patient Safety programme suggests that over 50% of adverse patient events occur at the interfaces of care1. It is important that the new initiatives for primary-secondary care working are supported, including face-to-face meetings between clinicians in line with Tim Davison’s vision of strengthening the ‘DGH function’ of hospitals. But more crucially, Refhelp is currently an arbitrary collection of policies and procedures, some not evidence-based and many not agreed with the GP community, the main users of the resource. ‘Nothing about me without me’ applies to GPs too! This has to be rapidly addressed, and the ideal would be a structure analogous to the Lothian Joint Formulary, with better support and input and agreement from both primary and secondary care clinicians.

4. Emergency admissions. This is by far the biggest ‘footprint’ associated with General Practice outwith the surgery1:

15 Scotland - Contracted and Non contracted services (including health community)

£2,500,000,000 PMS Expenditure Wider Community Health Footprint in Services Expenditure Secondary Care

£2,000,000,000

£1,500,000,000

£1,000,000,000

£500,000,000

y h s d y

£0 s e d g s P s n t g g s g r s f t c l n n F i n m t e n ) o n P n e i G n e i n n r a i i o a i s o

u t h w i t

O c i i n s . H s t e e e i e i t i b r l i o s t S r s d s i e t s g v i Q A n r H i . a a s s l s s u r b r

m i i i a s i m c l e ( e e

a M e V e y a e ) e n N p i e o

s t i a m r s L t t m b D i y r L H t s S i t c y

h e m (

l i d

d s u t d o n P g t i r m n e c P y i l y l i v d E d t n e t u A o l s b A c e i d r r O n i P l a i

i

G c h t e u s a i n d e t u n y o A e m v h d s l c M i F e s v r w i u

n u c i S r e a n H C m d c d m e e y a n D r t n e e a m D

m , c a o i S t m e N a n h

S H n A H R m C n o m g r o a n r u t l o e o e O C B E e c d P h C m C i O t e m r c i m O c E o D A C

Reducing emergency admissions requires intensive GP work, much of which cannot be delegated, and which is outlined in right hand column of the table in the Strategic Plan. GPs are key to managing uncertainty, chaos, the diagnostic process, decisions round admission and prescribing: their long-term relationship with the patient, and their role as custodians of the lifelong record are critical underpinnings to that process. Health service interventions to address health inequalities can also reduce admissions. We also know that consultation skills and relationships are crucial to concordance, health service use, self-management and the emotional and psychological care of patients.

Continuity of care has been shown to reduce admissions: “Continuity of care is important clinically as well as financially and plays a major role in reducing hospital admission as well as improving quality of care. A study examining the impact of continuity found that a 1% increase in the proportion of patients able to see a particular doctor was associated with a reduction of 7.6 elective admissions per year in the average-sized practice for 2006–07 and 3.1 elective admissions for 2007–08. This equates to considerable cost savings across a whole practice of £20,000 per year for a 1% increase in continuity and a saving of £2,641 per hospital admission”.2

Supported Self-Management is a complex process requiring patient ‘activation’ and a committed, trained primary care team with skilled GP input, but has been shown to reduce hospital admissions, days in hospital, outpatient visits, A&E attendances and medication expenditure3. In international comparisons the UK has very low levels of this sort on patient involvement, possibly due to a traditional reliance on our formal healthcare system4. As our starting point is a Primary Care deficit, shrinking the emergency admission footprint will only be achieved if there are more GP feet, both in and out of hours. …

5. Prescribing. Prescribing costs are second only to workforce costs in the health budget and savings can have a significant impact on overall health spending. Lothian doctors are the most efficient

16 prescribers in Scotland. Audit Scotland identified that GP prescriptions rose by a third in the seven years prior to 2011/12. This was attributed to the ageing population, development of QOF, a rise in clinical guidelines and new initiatives such as health checks. The report found that more than 900,000 patients aged over 50 are taking four or more different drugs. Yet spending on GP-prescribed drugs fell by £120m, or 11%, during this time, in part due to prescribing quality initiatives and excellent GP work.

It is possible to rationalise prescribing further but only if NHSLothian:

Continues to support and further invest in the excellent Lothian Joint Formulary;

Addresses specialist non-compliance with the LJF including facilitating formulary prescribing by junior doctors through appropriate IT, currently not available to them;

Campaigns nationally for improvements to our IT prescribing. Vision in particular is poor on safety, efficiency and flexibility;

Engages with the public to explain that in terms of prescribing we need to move from demand to need. This requires a very strong national publicity campaign (along the lines of Detecting Cancer Early) round minor illness. Patients need to know that we no longer prescribe antibiotics for uncomplicated sore throats, sore ears, coughs, flu and chest infections in healthy people; and ALL clinical sectors should give the same message and practice the same approach;

Notes that active approaches to prescribing management take considerable clinician time. One measure to free up GP time (and support quality) is to fund community pharmacists to take on work within practices. They could deal with queries, prescribing audits, medicines reviews, polypharmacy work as well as clinical work round hypertension, diabetes and other LTCs;

Recognises that it IS possible to reduce prescribing for those in the last years of life, particularly now that so much of our long-term prescribing relates to risk reduction. Scotland is a research world-leader in this area, because of the work of Professor Bruce Guthrie and his colleagues, and polypharmacy reviews are a strong element of our Scottish QOF. The excellent SG guidance outlines the process for this5– but again this work is time-consuming and requires significant GP input: community pharmacy time helps, but GPs are still required for consultation work with patients and their carers, and prescribing change. The primary impetus for polypharmacy work is to improve the patient’s health and life experience which require differing approaches according to age, function and illness. Yet it is estimated that nationally (and just looking at drug costs alone) stopping 2 drugs over the course of one year in those >65 on drugs from 10 or more BNF sections would save over £5.5 million5.

Identifies that substantial prescribing costs relate to adverse events – particularly AKI (acute kidney injury). It is estimated that 5-17% of all admissions relate to adverse drug reactions (ADRs)5, and these are rising, because of polypharmacy, the ageing population and particular drug combinations (eg ACE inhibitors and metformin which are highly effective but can prove dangerous with acute illness or poor patient understanding). Avoidance of ADRs– yet again - requires more GP input and monitoring, but is potentially another area of considerable saving.

6. Addressing Health Inequalities. The Strategic Plan demonstrates the relationship between poverty and admissions, and recent Scottish work has shown that a practice-based intervention is cost-effective

17 (admissions and prescribing savings) in terms accepted by NICE. The continued failure to implement primary care health service interventions therefore supports inequality.

7. Other approaches. The RCGP Compendium of Evidence6 makes other suggestions for NHS savings. Patient Decisions Aids are thought to have the potential of reducing costs for elective surgery and renal dialysis (with an estimated national reduction of costs of £100million p.a.) but require more GPs, spending longer with their patients with enhanced training in their use and care planning. It is thought however that this would be cost-effective.

8. Intermediate Care: see main document

9. Laboratory Testing: see main document

10. Expectations: see main document

Finally, and most importantly, much disinvestment is not needed – and many services are already pared down to a minimum. Examples such as podiatry and dietetics may seem marginal, but are crucial to maintaining the health of people with diabetes (amongst others), with massive potential savings ‘downstream’. We need more, and wise, primary care investment.

Other suggestions include:

Reduce the massive and duplicate bureaucracy endured by all Community nursing teams;

Automatic electronic script transfer to chemists;

Reuse of unopened drugs;

Implementation aspects of NICE Guidelines where they have been shown to be cost-effective (3 obvious omissions in Lothian are BNP, full LARC provision and earlier referral of those with varicose veins).

Perhaps we should have a GP competition to think of more?

References

18 1. Board Primary Care Leads Discussion paper: A Collaborative Approach to delivering General Medical Services in Scotland (2013). Establishing a route to the 2020 vision for General Practice.

2. RCGP: Patients, Doctors and the NHS in 2022 – Compendium of Evidence. 3. Care Planning. Improving the Lives of People with Long Term Conditions. Nigel Mathers et al. Clinical Innovation and Research Centre 2011 (RCGP publication).

4. ‘Engaging Patients in Healthcare’; Angela Coulter; 2011. 5. ‘Polypharmacy Guidance October 2012’; NHS Scotland. Developed by The Model of Care Polypharmacy Working Group; Quality and Efficiency Support Team; Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates. 6. RCGP: Patients, Doctors and the NHS in 2022 – Compendium of Evidence.

19 Appendix 3: Out of Hours – Dr Sian Tucker

LUCS was initially established in 2004 to provide urgent non-emergency primary medical services to the population of NHS Lothian when their own GP practices were closed. Over the last ten years there has been a gradual increase in workload, coupled with a change in the expectations of what services LUCS will provide. There is also a national and local shortage of GPs able and willing to work within the out-of-hours environment. LUCS is facing the same challenges as in-hours GPs, namely an increasing population in general, but in particular increasing numbers of frail elderly multi-morbid patients being looked after in the community. Despite the current workforce and workload challenges, LUCS performed very well in the 2014 patient experience survey achieving an overall rating 2% above the Scottish average. The cost per patient contact in LUCS for 2012/2013 was £67.92 which is the lowest for any Board in Scotland and a reduction from £71.17 in 2010/11.

During the out-of-hours period, LUCS provides the only senior clinical decision-makers working within the community and has now become a focal point of contact for all healthcare and other service staff working out of hours.

LUCS therefore currently provides: Cover for NHS Lothian continuing care facilities; Telephone advice to a number of different professional groups out of hours (including community pharmacists, paramedics, social workers, police, laboratories, minor injuries units, care homes); Increased workload with complex frail elderly patients; Primary medical care to patients redirected from emergency departments; Palliative care in the community as more patients choosing to die at home, and a strategic intention that these numbers expand further.

In March 2014 a review of LUCS was commissioned, and will report in September 2014. The interim LUCS Improvement Plan and draft review report have influenced the strategic direction of LUCS to ensure it can provide robust safe efficient patient care in the future.

I have laid out the priorities identified by the review and by the Service to ensure the continued excellent work of LUCS below:

Premises-ensure LUCS has appropriate accommodation at each of its 5 sites to carry out its work.

Workforce-ensure recruitment and retention of appropriately trained GPs and Emergency Nurse Practitioners (ENPs). This will involve improving terms and conditions for staff including a ring- fenced study leave budget and career progression pathways. It will also involve a realignment of the workforce to ensure that staffing and opening hours at each base are in line with patient demand.

Community support-provide out of hours community support to facilitate GPs to do what only GPs can do, ensuring best use of resources. This would include increased palliative care support to provide care for the increasing number of patient who wish to die at home. It would also involve increased community resources to deal with the increasing number of complex frail elderly now being managed within the community.

LUCS management- increase the current clinical and service management team to ensure robust clinical governance and advice available throughout the 118 hours per week that LUCS works.

20 National out-of-hours’ indicators- increased clinical management will facilitate reporting and learning from the new Health Improvement Scotland indicators. This will co-ordinate with our quality improvement team and improve patient access and safety.

Public expectations- communication with the public to educate and inform them how best to access appropriate healthcare and ensure they contact and access the right service for their medical need in a timely manner. This may be pharmacy, optometry, dentist or primary or secondary care.

Increased engagement with Health and Social Care partnerships- to enable clinicians to access social care for patients in a timely manner, where this is required to avoid inappropriate attendance and admission to hospital. To understand and support (where possible) their development of services to manage the increasing numbers of frail elderly within the community. This is in line with 20/20 vision of patients being managed at home or in a homely setting.

Community hospitals- ensure that the 15 community hospitals within Lothian have the appropriate level of medical input, including at weekends, evenings and public holidays

Professional to Professional telephone line- continue to support this excellent and essential resource to provide clinical advice to professionals within the community. This should be extended to in-hours so that the service can be provided 24/7 when needed.

Relationship with secondary care-this is essential to ensure patients are treated in the area most appropriate for their medical needs. There is a flow of patients from LUCS to the Emergency Departments in Lothian and also a flow of patients from the EDs to LUCS where primary care is a more suitable venue to manage the patient. LUCS also interacts with other secondary care specialities and this dialogue must be maintained for the benefit of patients.

NHS24, SAS and National Out-of-Hours. LUCS has regular meetings with all three group mentioned. NHS24 and SAS are essential components of the patient pathway and continued feedback on how all services can improve is an important part of the LUCS clinical management job. The National Out of Hours Group has close links with the above partners and with the Scottish Government and again the learning here is vital for the Service.

Dr Sian Tucker Clinical Director LUCS

21 Appendix 4 : Lipid Clinic Proposals with thanks to Dr Sara Jenks.

This would involve patients with confirmed familial hypercholesterolaemia with good lipid levels being kept under virtual review by the clinic - by attending their practice for blood tests once a year. The results would then be reviewed and managed in secondary care (see attached flow diagram – next page - which shows exactly how this clinic would work).

There are several reasons why we at the lipid clinic are keen for the introduction of this clinic:

1. It will help us best utilise our clinic resources. Due to the increase in genetic testing for FH more patients are being diagnosed each year and our clinic numbers and waiting times are increasing. There are no additional resources for the clinic available and if we cannot set up this virtual clinic it is likely that we will have to discharge many of our more stable patients back to primary care for long- term follow-up with yearly lipid levels. This will result in an initial increase in primary care work load and if there is no system in place to remind patients to attend for their yearly lipid check many patients will be lost to follow-up. In untreated men with FH half will have an MI before the age of 50 and it is therefore important that these patients are properly followed-up.

2. It will benefit patients with well controlled FH as all we do at their OPA is check their blood tests and many patients have indicated that they would prefer to attend their practice for blood tests and be seen in a ‘virtual way’. It is also a more sustainable way of keeping them under longterm follow-up which will hopefully ensure that they receive the best possible longterm care and they will be able to contact the lipid clinic team should they wish to arrange a telephone consult or a standard OPA.

22 23