Women At War

This poster shows Uncle Sam's hand pointing through the flag. Slogans like this were used to create a sense of patriotism, necessity, and efficiency.

Trying to hold the home front together while there was a war waging abroad was not an easy task. Women were not only asked to complete the daily chores that were normally expected of them, but they were asked to go to work. Suddenly their very private lives were turned into a very public and patriotic cause. The changes that women underwent in the late 1930's and early 1940's would be felt by generations to come.

Traditionally the woman’s place was thought to be in the home. She was responsible for cooking, cleaning, taking care of the children, and looking her best. So when the war broke out, and it was clear that America would not be able to win the war without the help of their women, the "traditional" housewife and mother turned into wartime worker. A Call to Arms

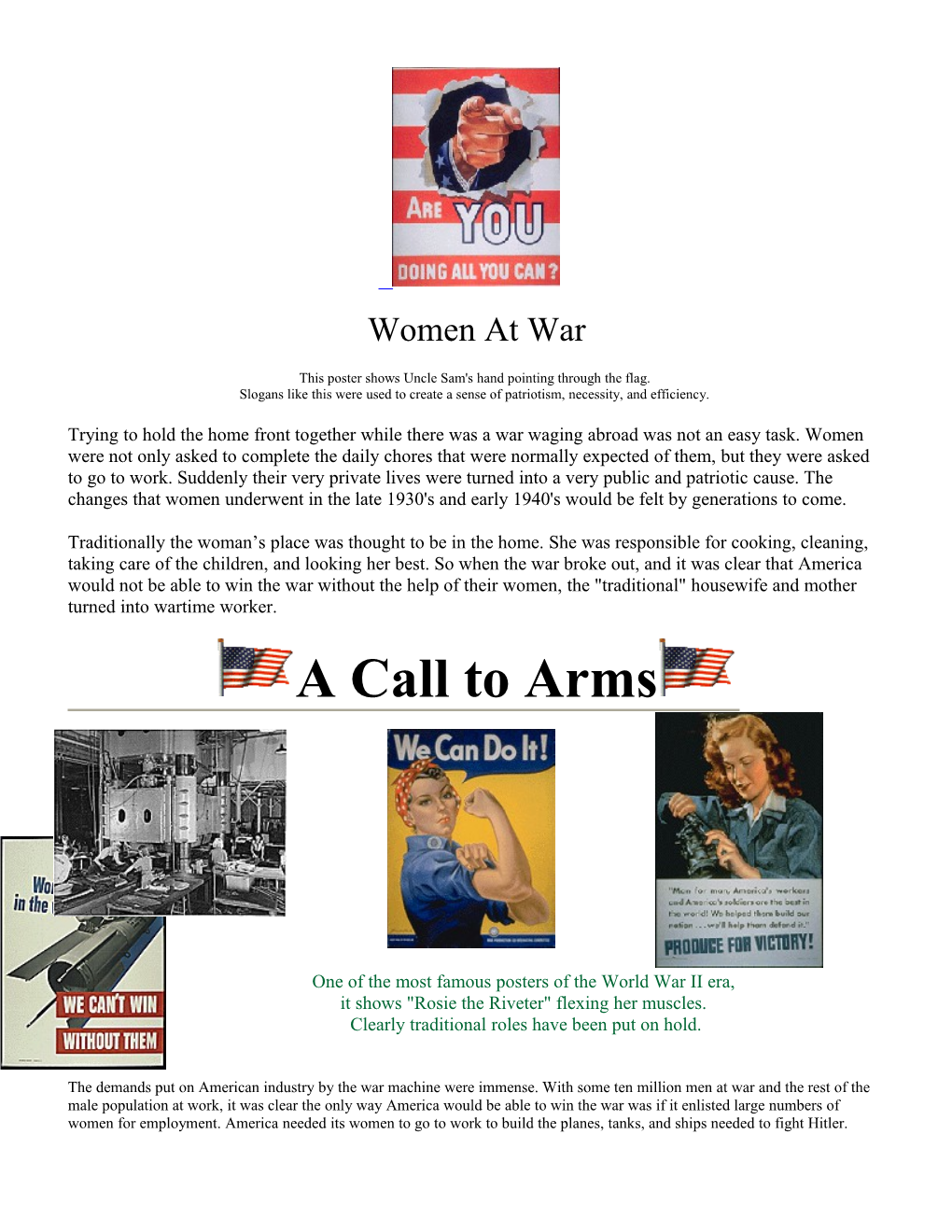

One of the most famous posters of the World War II era, it shows "Rosie the Riveter" flexing her muscles. Clearly traditional roles have been put on hold.

The demands put on American industry by the war machine were immense. With some ten million men at war and the rest of the male population at work, it was clear the only way America would be able to win the war was if it enlisted large numbers of women for employment. America needed its women to go to work to build the planes, tanks, and ships needed to fight Hitler. World War II, more so than any other war, was a war based on production, and so it was time to bring American women into industry.

So the government teamed up with industry, the media, and women's organizations in an effort to urge them to join the labor force because telling women it was their "patriotic duty" to go to work. But patriotism was not the only incentive that the War Manpower Commission used to lure women into the workforce. Many recruitment programs used the idea of increased economic prosperity to attract women into the workforce. In fact some posters went so far as to glamorize war work, as well as stress the importance women working in non-traditional jobs.

Still much of the propaganda of the time used emotional appeal paired with patriotism. Women were constantly being reminded that their husbands, sons, and brothers were in danger because they were not receiving the supplies they needed. Slogans such as "Victory is in Your Hands," "We can do it!" and "Women the war needs you!" were all used to convince women that their country's need were more important than their individual comfort.

As a result of the propaganda American women, whether they were motivated by patriotism, economic benefits, independence, social interaction, or necessity, joined the workforce at never before seen rates. In July 1944, when the war was at it's peak over 19-million women were employed in the United States, more than ever before.

Applying for a job was not necessarily as easy as it appeared to be. While their boys were fighting for equality and human rights abroad, American women were getting discriminated against at home. Though women were turning out for jobs at alarming rates, many employers refused to hire them (even though they had unmet labor requirements.) Some employers out rightly refused to higher women, while others set ridiculously low quotas for women, and still some agreed to employee women, yet they refused to offer them jobs previously "assigned to men." These practices left women feeling very confused as to how America wanted its women to behave. Most people believed that men should be the sole bread winner in the family, and as a result women were among the last hired in the early stages of the war.

Though several million women were hired, they were not necessarily treated the same as their male counterparts. In 1942, the National War Labor Board (NWLB) attempted to erase some of the long-standing inequalities in women's pay, when they decided to employ an equal pay principle. According to the NWLB, women would be paid the same as men for the same or comparable work. However, these standards were seldom enforced. Most employers thought that the traditional women's pay scale was acceptable, and some reasoned there was no need to make women's pay comparable to men's because women's work was easier. But this was far from the case. Women who joined the labor force as a result of World War II were often referred to as "production soldiers." Their standard work week was 48 hours, though many women frequently worked overtime, Sunday was their only day off, and most vacations and holidays were cancelled

Though a popular example of a wartime woman worker "Rosie" did more than just "rivet." Women of all ages operated large cranes which were used to move heavy tanks and artillery. Some women loaded and fired machine guns and other weapons to make sure they worked. Other women operated hydraulic presses, while some worked as volunteer fire fighters. Some women who formerly worked as saleswomen, maids, or waitresses, took over more essential jobs such as welders, riveters, drill press operators, and taxi cab drivers. Women found themselves in participating in every aspect of the war industry from making military clothing to building fighter jets, American women worked day and night.

Posters encouraged all citizens to participate in the war effort in every possible way -- growing, conserving, saving, and producing.

Woman Fight the War from Home Not all women were asked to join the workforce. Infact, Paul McNutt, the Chairman of the War Manpower Commission, issued a 1942 directive which stated, "no women responsible for the care of young children should be encouraged or compelled to seek employment which deprives their children of essential care until all other sources of supply are exhausted." This directive paired with the fact that there was much public resistance to the idea of working mothers, contributed to the low rate of women aged 25 to 34 that participated in the labor force. These women who elected not to go to work contributed to the war effort in a different way. Suddenly as a result of the war much of the supplies that a housewife used to complete her everyday chores were gone. A 1940's housewife could not buy a staple like sugar at the grocery store, because the sugar cane supply was significantly diminished. What sugar was left was vital to the war effort, because it makes molasses; molasses makes ethyl alcohol; and alcohol makes the powder which fires guns and serves as Torpedo fuel, dynamite and other chemicals desperately needed by the American military. The availability of this product to the American people was very limited and as a result it was considered a "rationed" item. This meant that a housewife could only purchase so much of it at a time, assuming of course that she could find it at the store to begin with.

Other items that women needed to ration were silk, nylon, rayon, cotton, and wool. All of these materials were in high demand because they made parachutes, aircraft and military clothing, tents, and even gunpowder bags. Food items that were rationed were coffee, tea, butter, and meat. As a result, housewives had to drive around to several different markets to find the supplies that they needed to create a well balanced meal. This too created a problem given the fact that gasoline was rationed as well.

Another obstacle that the early 1940's housewife ran into was the shortage of steel. In 1943 civilians were only allotted 15% of the nation’s steel production. This caused the rationing of such items as bottled, canned, dried, and frozen vegetables, as well as canned fruits, juices, and soups. Women who lived in big cities felt this squeeze more than ever, while women who lived on farms and in small towns were able to garden and preserve their own supply of fresh produce. So in an effort to help the war effort, the government promoted "Victory Gardens." These were small gardens that family could have in their back yard which produced tomatoes, lettuce, and beans and other produce that would normally be found in the grocery store.

The left poster suggests that a woman should both work and be a mother, once again demonstrating the mixed

As evident by the above section, being a housewife during the war was not easy. These women were still expected to keep house, dress, and cook as they had before the war started, however they had to do so with very limited resources. It seemed like every time they turned around another product was being rationed, and it was their job to learn how to deal with it. Women became excellent troops of the war effort in their own homes for they did, for the most part, what they were told to do by the U.S. federal government. Impart the rationing system was so successful because of the great strides made by American women

Rosie the Riveter:

The Typical Life of a Wartime Working Wife and Mother

In order for women to fulfill both their function as a wife and mother and their duty to country, some women took night jobs. The typical day for a wartime woman who had a night job is explained by Doris Weatherford in her book American Women and World War II. She uses the example of a woman named Alma, who because she worked nights would often times get home just as her children were getting ready to leave for school. Immediately she would send her children off to school, then she would eat breakfast, clean the mess in the kitchen, and then finally go to bed around 10 am. She would get about an hour and a half of sleep before the alarm went off to tell her that her kids would be home for lunch. When they got home she would feed them, and send them off again. After that it was back to bed until 3 pm, when they arrived home again. Once the children were home for the day she would clean the house, do the laundry (if there was time), and then cook dinner with the limited amount of supplies available to her. The family would eat when her husband got home around 6pm, and after she cleaned the kitchen she would take a nap until she needed to leave for work at 10pm. The average woman who worked nights and still took care of her family averaged about five to six hours of sleep a day, but they were never consecutive.

And despite of all of the responsibilities and burdens women endured during the war years, housework was almost never shared. Most men did not lift a finger to help their wives, because they felt that they were in fact doing their share by allowing their wives to work. Most of the accounts of Rosie the Riveter suggested that despite her daily struggles, she asked for nothing and continued to meet her family responsibilities, as well as the new responsibilities dictated to her as a wartime worker. By the end of 1943, one-third of women war workers were mothers of children living at home. For these women, life was very arduous, because the balancing act between one's home and one's job was more difficult then than it is now. The reason for this is that housework in the 1940's was far more laborious than it is today. This was the era of cooking from scratch and washing dishes by hand. Washing clothes in the 1940's consisted of wringer washing machines, a tub of rinse water, and an outdoor clothes line. Clothes dryers or dry cleaners did not exist, and housewives starched and pressed clothes by themselves. In some cases women had to devote a whole day to doing laundry because it was such a tedious task. In addition to this burden, Banks were only open in the mid-day hours, and so women who worked jobs during the day had a difficult time keeping their financial obligations in order. There were also very few grocery stores that stayed open at night to accommodate women who worked. Wartime working women, often times, devoted their Sunday's off to cleaning and catching up from what they could not complete during the week. Because of the fact that some women had a hard time completing such tasks as going to the grocery store and bank some women literally had to quit their jobs in order to fulfill their job to their family.

Mothers who joined the workforce while their husbands were away or mothers who had small children not yet in school had an even bigger burden to bare due to the lack of child care facilities available to them. Section B of article IV of Paul Mc Nutt's 1942 War Manpower Commission directive stated that, "If any such women are unable to arrange for satisfactory care of their children...adequate facilities should be provided...Such facilities should be developed as community projects and not under the auspices of individual employers or employer groups."

However, cities did not know how to handle such a dilemma and instead of forcing industry to deal with the problem, the burden was shifted to state and local governments. Though the Landam Act, a federally subsidized child care system, attempted to deal with these problems it fell short. At the programs peak it only had about 3,000 child care facilities, which cared for about 130,000 children. The government simply could not develop a comprehensive system for dealing with the large number of mothers going to work. With so much else to do, childcare facilities were not regarded as high priority, and as a result some women quit their jobs to take care of their families.

There was a small faction of women however, that were against America's participation in the war. They called themselves the Mother's Movement and they were comprised of anywhere from five to six million. They were devout Protestants who aligned themselves with the ideals of the Women's Christian Temperance Union. Though they were not a particularly strong force they did conduct some demonstrations as well as publish some articles professing their beliefs.

The Effects of the War on Women

When America achieved victory in August of 1945 millions of people celebrated. The war was finally over and millions of men would finally be able to return to their homes. However, when the fighting stopped, the war machine, which had mobilized millions of women to work, ceased. No longer was there a need for women to leave their husband and children to work eight hours in a factory, they could once again stay at home and take care of their families. But for some women this just wasn't enough anymore.

The development of wartime economy had given women more freedom than they had ever had before. Though they did face some discrimination in the workforce it was minimal compared to that which they were privy to in pre-world war II times. For the first time, women were able to experience some sort of social and economic mobility. Suddenly women were faced with choices, and by exercising these choices they were able to explore their own individuality and independence. With the war over and the break up of the war machine women who were urged to go to work to support their country were now in jeopardy of losing their jobs.

But the future of women's place in the workforce did not depend solely on the state of the post war economy, in fact much of it would depend on the women themselves. For the past three years women were subjected to long hours, little benefits, low-cost and low-quality child care facilities, not to mention almost unprecedented physical demands, it was possible, that for many women losing their job was a blessing. The fact was that only time would tell how women would react to the postwar period.

Another factor in deciding the postwar place for women in the workforce was public opinion. Many people just assumed that American women would just return to their homes voluntarily. More still viewed the American homemaker turned "production soldier" would understand that her position was as temporary as a soldiers. They reasoned that millions of men were asked to leave their job to become soldiers, and when the war was over they were expected to return home to work.

The fact of the matter is that there was no one typically feminine response to the postwar era. The choices that women made and the reasons why they made them were as unique and individual as they were themselves. Some women were glad when the war ended because that meant that they could go back to the home where they felt they belonged. Other women returned home not because they wanted to, but because their husband and much of the American society believed they should. Still other women left their jobs, because the return of their soldiers meant the ability to resume pre-war plans (i.e. marriage or pregnancy.)

Yet there were some women who elected to stay at work. They enjoyed their newfound independence, and the income they had brought in was either important to their own livelihood, in the event that they were single, or their families

One thing is for certain the effects of World War II would be felt for years to come. Women had experienced new opportunities, a sense of independence, and were experiencing their own individuality. Though some of the women that continued to work after the war did receive wage cuts and some even received demotions, they had made progress. The war allowed women to make decisions, and it gave them a chance to fight for their rights. There is no doubt that the consequences of the World War II (the discrimination, job cuts, and wage inequalities) led to the development of many of the civil rights movements of the 1950's.