PROJECT BRIEF

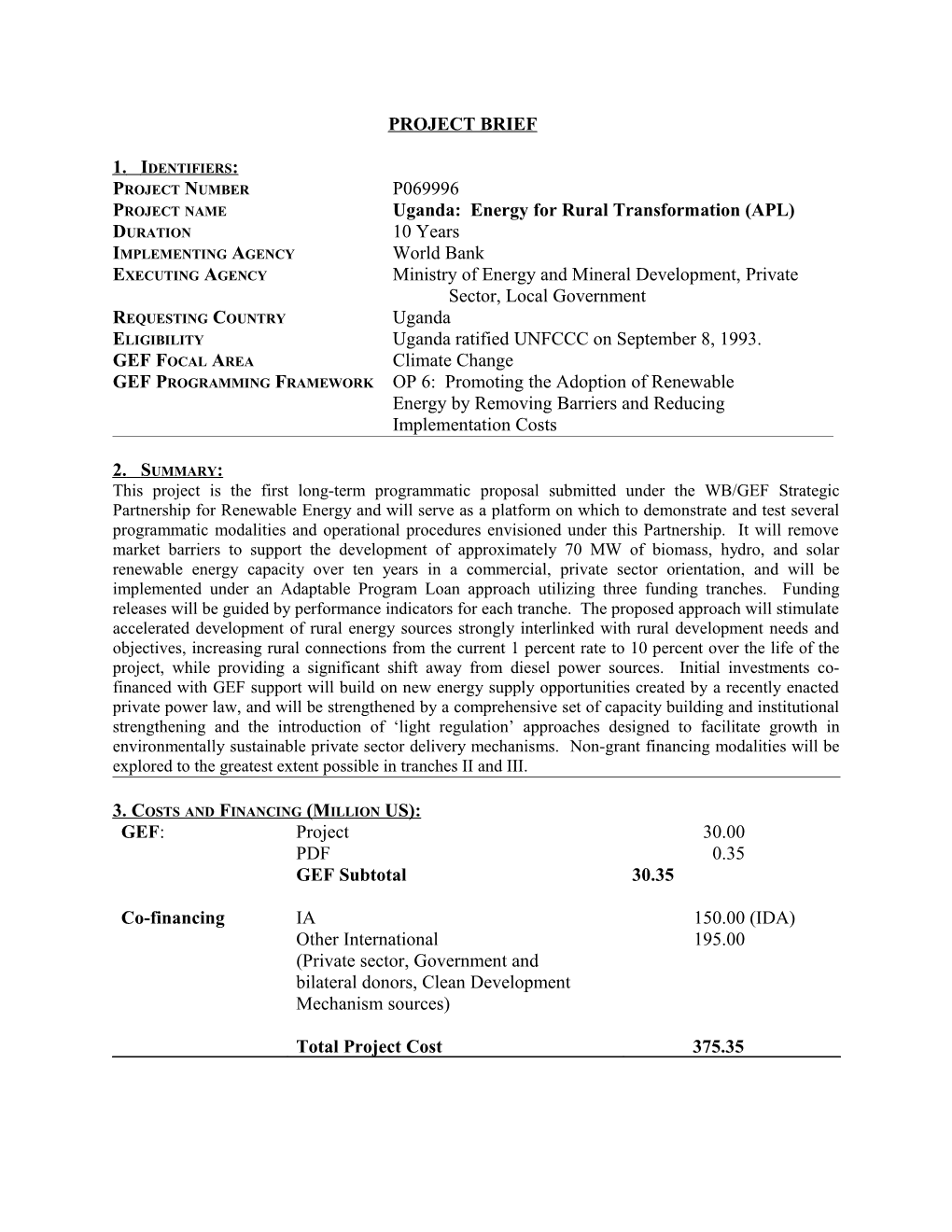

1. IDENTIFIERS: PROJECT NUMBER P069996 PROJECT NAME Uganda: Energy for Rural Transformation (APL) DURATION 10 Years IMPLEMENTING AGENCY World Bank EXECUTING AGENCY Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development, Private Sector, Local Government REQUESTING COUNTRY Uganda ELIGIBILITY Uganda ratified UNFCCC on September 8, 1993. GEF FOCAL AREA Climate Change GEF PROGRAMMING FRAMEWORK OP 6: Promoting the Adoption of Renewable Energy by Removing Barriers and Reducing Implementation Costs

2. SUMMARY: This project is the first long-term programmatic proposal submitted under the WB/GEF Strategic Partnership for Renewable Energy and will serve as a platform on which to demonstrate and test several programmatic modalities and operational procedures envisioned under this Partnership. It will remove market barriers to support the development of approximately 70 MW of biomass, hydro, and solar renewable energy capacity over ten years in a commercial, private sector orientation, and will be implemented under an Adaptable Program Loan approach utilizing three funding tranches. Funding releases will be guided by performance indicators for each tranche. The proposed approach will stimulate accelerated development of rural energy sources strongly interlinked with rural development needs and objectives, increasing rural connections from the current 1 percent rate to 10 percent over the life of the project, while providing a significant shift away from diesel power sources. Initial investments co- financed with GEF support will build on new energy supply opportunities created by a recently enacted private power law, and will be strengthened by a comprehensive set of capacity building and institutional strengthening and the introduction of ‘light regulation’ approaches designed to facilitate growth in environmentally sustainable private sector delivery mechanisms. Non-grant financing modalities will be explored to the greatest extent possible in tranches II and III.

3. COSTS AND FINANCING (MILLION US): GEF: Project 30.00 PDF 0.35 GEF Subtotal 30.35

Co-financing IA 150.00 (IDA) Other International 195.00 (Private sector, Government and bilateral donors, Clean Development Mechanism sources)

Total Project Cost 375.35 4. OPERATIONAL FOCAL POINT ENDORSEMENT: Name: C. M. Kassami Title: Deputy Secretary to the Secretary Organization: Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development Date: September 6, 1999

5. IA CONTACT: Christophe Crepin, GEF Regional Coordinator Tel. (202) 473-9727; Fax : (202) 522-3256 World Bank Group - Global Environmental Facility Strategic Partnership for Renewable Energy Background Note to Accompany the First Project Proposal

Uganda: Energy for Rural Transformation is the first project submitted under the World Bank/Global Environment Facility Strategic Partnership for Renewable Energy. This cover note summarizes some of the unique strategic features the Uganda project, as well as the larger context of future projects likely to be proposed under the Partnership and the programmatic and operational approaches anticipated for the effective processing and implementation of these initiatives.

Background

Despite the availability of GEF support for renewable energy barrier removal projects for nearly a decade, the ability of GEF and its implementing agencies to stimulate renewable energy development has remained hindered by a plethora of competing development demands and limited development capital in the client countries. To build on the valuable learning and some notable project successes that have resulted from GEF Climate Change investments, the World Bank/GEF Strategic Partnership for Renewable Energy is working to engage client countries on a long-term, systematic approach rather than on the basis of individual projects and single technologies, and in a context that is inextricably linked with the development priorities of the country. As reviewed and approved by the GEF Council in May 1999, one of the primary modalities for achieving these aims is to use Adaptable Program Loans (APLs) to more strongly establish Renewable Energy Technologies (RETs) in the Bank’s financing operations, providing phased, sustained support for the development of long-term RET programs while strengthening client country commitments to promote RETs.

The Uganda Rural Energy for Development proposal is for a $375 million IDA and donor- suported project which will include $30 million in GEF resources to remove market barriers in development of approximately 70 MW of biomass, hydro, and solar renewable energy capacity in a commercial, private sector orientation. The project will be implemented under an APL approach utilizing three funding tranches over ten years. The proposed approach will stimulate accelerated development of rural energy sources strongly interlinked with rural development needs and objectives, increasing rural connections from the current 1% rate to 10% over the life of the project, while providing a significant shift away from diesel power sources. Initial investments co-financed with GEF support will build on new energy supply opportunities created by a recently enacted private power law, and will be strengthened by a comprehensive set of capacity building and institutional strengthening and the introduction of ‘light regulation’ approaches designed to facilitate growth in environmentally sustainable private sector delivery mechanisms. Specific quantifiable indicators for each of the three tranches include: Quantitative Project Objectives

Under the APL approach, the triggers for proceeding to Tranche II are linked to the accomplishment of the objectives of Tranche I. These triggers (with additional detail to be developed during project appraisal and PAD documents for each tranche) will be clarified in terms of the calculated baseline and related milestones for each of the different phases at the time of submission for CEO approval and will be based on the following (with specific GEF related triggers presented in italics):

Triggers for Phase II

Establishment of regulatory system, RE Fund, wheeling system and procedures, and a workable intermediation mechanism for commercial finance Construction of renewable energy power generation facilities in the range of 20-25 MW, with a GEF share in total cost of about 20-25%, and the rest of the financing to come from a combination of Bank and commercial financing, but not from other external CDM-type sources; Sales of solar pv systems: about 7,000-10,000 household systems and 125-175 institutional systems, with a GEF share in total cost of about 20-25%, and the rest of the financing from a combination of Bank and commercial financing (but not from external CDM-type sources); Finalization of long-term renewable energy capacity building strategy and action plan, including financing of recurrent costs of renewable energy projects, and other evidence of Government commitment to renewable energy (to be discussed with Government)

Triggers for Phase III

Ttriggers for Phase III would be linked to the accomplishment of the objectives of Phase II. The Phase III triggers, with additional details to be developed during PAD preparation, represent many of the same factors as the Phase II triggers, but at a higher level of development (GEF related triggers are presented in italics):

Fully operational regulatory system, RE Fund, wheeling system and procedures, Fully functioning main grid rural extensification and independent grid system programs, and sales of solar pv systems, Establishment of regional best practice level capacity to promote and undertake renewable energy development; Construction of additional renewable energy power generation facilities in the range of 20- 25 MW, with a GEF share in total cost of about 15-20%, and the rest of the financing to come from a combination of Bank and commercial financing (but not from external CDM- type sources), with another about 10 MW not supported by GEF, Sales of solar pv systems: about 50,000-75,000 household systems and 200-300 institutional systems, with a GEF share of about 15-20%, and the rest of the financing to come from a combination of Bank and commercial financing, but not from CDM-type sources)

2 1. Project components (Tranche 1): Indicative Bank- % of GEF- % of Component Sector Costs % of financing Bank- financing GEF- (US$M) Total (US$M) financing (US$M) financing Grid-based Energy 39 52 17 44 7 58 Distribution/Generation Independent Grid Systems Energy 28 37 8.6 30 0.5 4 Solar PV Systems Rural 2.5 3 1 40 1 8 Pilots Energy/Rural 0.5 1 0.4 90 Technical Assistance Energy/Rural/ 5 7 3 60 3.50 30 Financial Phase 1 Total 75 30 40 12 16

Project components (Tranches 2 and 3) Indicative Bank- % of GEF- % of Component Sector Costs % of financing Bank- financing GEF- (US$M) Total (US$M) financing (US$M) financing Grid-based Distribution/Generation Energy 9 50 Independent Grid Systems Energy 4 22 Solar PV Systems Rural 2 11 Pilots Energy/Rural Technical Assistance Energy/ 3 33 Rural/ Financial Phase 2 and 3 Total 300 120 18 6

These indicative targets will be confirmed during appraisal, and parallel WB targets for long- term operation of the APL. The baseline existing at the beginning of each trance will be clarified to the extent possible with this information incorporated into targets and triggers for the appropriate tranche. Because of the practical difficulties of forecasting 4-7 years in the future, and to retain the flexibility provided by the APL mechanisms, targets for tranches two and three may require some adjustment during appraisal. Similarly, additional details on co-financing will be developed during appraisal and PAD development for each tranche. Regardless of the ultimate source of such co-financing (World Bank, bi-lateral, private, or other), the objective will be to provide funds at the level closest to commercial terms as possible. Investments in the 2nd and 3rd tranches will also pursue financing from emerging Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) sources, but in no event will GEF funds be combined with CDM financing.

Specific GOU commitments (including agreements to provide specific policies related to RE), will be confirmed in a Letter of Development Policy to be developed during appraisal as the foundation of their objectives and agreements under the Adaptable Program Loan (APL) arrangement with the World Bank. This Letter will confirm the specific benchmarks for program progress at various stages of implementation required for release of subsequent tranches of funds (including GEF co-financing). Any significant deviation from these indicators will either require a delay in the release of the next tranche, or consideration by Council to approve significant changes in the targets, to be determined by the GEF CEO.

The calculated value of the cost of carbon of about $ 46 per ton carbon is based strictly on the supported investments, and does not take account of any multiplier effects or “programmatic

3 effect” which will occur, not just in Uganda but also in the neighboring countries of Tanzania, Kenya, Sudan and Democratic Republic of Congo, particularly from the solar PV component. As this is the first project in the region to support the systematic development of a number of renewable energy technologies, it is expected that the multiplier effect will be in the range of 2 or 3, resulting in a long-term GEF cost of $15-23 per ton of carbon. These multiplier effects will be considered as additional indicators related to tranche release and will be addressed to the degree possible in the relevant PAD document.

Consistency with Strategic Partnership Principles

This proposal, as the first project to be presented under the World Bank/GEF Strategic Partnership for Renewable Energy, represents a watershed for the GEF, WBG, and client country relationship in terms of initiating a variety of project modalities designed to encourage long-term renewable energy development pathways in the developing world. It is consistent with several of the Strategic Partnership modalities endorsed by the GEF Council at their May 1999 meeting:

A long-term programmatic approach focussed on sustainable private sector participation - The proposed project is targeted at building effective bridges to private sector market development and financing capabilities to ensure commercial sustainability. In contrast to the ex-ante definition of the entire project and a linear implementation path, this project is approached through an 10-year APL implemented in three tranches of approximately 3 years each, and combines long-term ‘stretch’ targets with a relatively high level of flexibility as a means to achieving credible programmatic goals. The APL approach provides phased and sustained implementation support on a scale and time capable of shifting sector direction rather than simply providing a technology demonstration, while providing multiple entry points for private sector players to encourage investment in market development and permit a logical maturation of commercial delivery and finance mechanisms. The proposed Uganda project proposes specific investment levels in a well defined set of first tranche sub-projects. Subsequent tranches propose indicative investment levels across an expanding set of similar sub- projects. The actual investment levels for subsequent tranches (and corresponding GEF co- financing) will be determined by continued progress in meeting targets for earlier tranches.

Increase in GEF resources with significant leveraging - The project proposes ambitious, long-term targets (with a GEF contribution proposed that is the highest for the World Bank’s operations in the sub- Saharan Africa region). It provides significant (over 11: 1) leveraging of GEF resources, particularly for the investment components, where the GEF incremental costs are expected to decline over time – this leveraging ratio is significantly higher than the range of 3:1 or 4:1 leveraging suggested in the WB/GEF Strategic Partnership proposal approved by Council. Program Co-financing Partners for financing include a number of bilateral donors, such as Denmark, Sweden, and Norway; in terms of preparation, they include a number of NGOs, such as ActionAid and Acord; and in terms of consultation, they include associations such as Uganda Renewable Energy Association and Uganda Manufacturers Association. By increasing the scale and tenure of projects to where they can be seen as contributing to a larger country- based rural development strategy, the APL approach is key to engaging the country government overall (not simply a subset of renewable energy ‘converts’) and in accessing significant co-financing from other bilateral donors.

Adherence to established principles of incremental costs – The project has a strong basis in strategic use of incremental cost financial support to overcome barriers to the programmatic use

4 of renewable energy technologies, using GEF support to build policy support and market activity over time to respond to sector needs and create new opportunities for systematic use of renewables. In the case of Uganda, this support will be delivered initially via ‘smart subsidies’ as a first step in stimulating private sector power entrepreneurs to invest in a wide spectrum of renewable energy sources – as opposed to diesel – to be provided to customers on a commercial basis. GEF support will be coupled with technical assistance for ‘light regulation’ that is more appropriate for these smaller private power operations and ongoing technical assistance to replicate lessons from initial applications further into the rural areas.

This project will demonstrate a practical context for rural energy and development efforts, ensuring a continued pace in rural energy services that unfortunately are often dealt a setback following initial utility privatization efforts. The use of GEF funds in this project reflects the fact that there is no single “quick-fix” but a continuum of efforts that will require less concessional incremental cost support over time, permitting a gradual transition from grant support through approaches such as non-grant contingent financing, ultimately resulting in the emergence of an RE sector on commercial par with conventional energy technologies.

For Uganda, the contrast with the baseline (which in the absence of this project will result in limited rural development and an off-grid energy path supported primarily by diesel generators) is striking. While there will be significant local benefits in terms of cleaner energy supply and local economic development, the GEF incremental cost element addresses only the additional cost of removing the initial investment risks related to shifting to renewable technologies; thus the incremental costs are those over and above the willingness of customers to pay for energy services.

Subsequent tranche investments will be formulated to minimize the GEF incremental cost element required to stimulate and maintain local entrepreneurial interest in pursuing RE projects. Non-grant financing options, including contingent arrangements or partial risk guarantees for renewable energy power generation will be considered and promoted in this context, and for the Uganda project are likely to be most relevant for mini-hydro, wind and geothermal resources. Such arrangements will be explored in view of the level of market, financial, perceived, and other risks that remain at the time when these future investments are considered. The overall viability of contingent financing and specific level of investment requirements that can be shifted to contingent arrangements will be a function of the pace of barrier removal efforts and the level of competition offered by other conventional energy sources in relation to prevailing Ugandan costs for RE sources. The final form and total cost of the contingent grant financing required to leverage adequate support from other financing sources will be determined through negotiations with private power entrants.

A Country Driven Process - Renewable energy is widely viewed in Uganda as a local, indigenous resource, a particularly important consideration for a land-locked country that is now heavily reliant on imported energy sources, transported long distances over land. To minimize the risks of supply interruptions and price volatility, Uganda recognizes that additional efforts are required to encourage development of indigenous energy resources where they are available and economic. For this reason, the Government has forcefully declined to consider thermal-based main-grid power generation, even in the current period when there is a severe shortage of power. Uganda has already taken the significant first step in their passage six months ago of private power legislation that will encourage rapid development of additional power resources. Further, in Uganda, key measures related to power sector reform, such as a

5 new Electricity Act, have already been enacted, and they provide a level playing field for renewable energy.

The project represents a true partnership with Uganda, providing a dedicated line of investment capital as targets continue to be met under a long-term performance-oriented framework. By integrating the renewable energy focus of the project so strongly with Uganda’s rural development objectives (and by association, with the WBG’s poverty alleviation agenda), the Partnership heightens the country’s commitment and facilitates a pursuit of global benefits that would otherwise not be economically possible. This project makes it clear that GEF resources should not be used simply to make a country client indifferent to the use of renewable energy, but should highlight the unique qualities that renewable energy technologies and markets can offer for inter-linked rural and commercial development. In subsequent tranches, the country role is expected to be more firmly established through the use of in- country intermediaries that can assist in the identification, appraisal, and implementation of sub-projects and work with the Rural Energy Fund to be established under the project to make continued investments.

Lessons for Continued Implementation of the WB/GEF Strategic Partnership

Preparation of the Uganda project has shown that it takes additional time and resources to complete the institutional and policy arrangements necessary to support larger and relatively complex project, and to forge relationships with a broader set of stakeholders. While this will likely continue to be true for additional Strategic Partnership proposals, the availability of GEF- approved model for a Strategic Partnership project will also provide significant opportunities to promote the Strategic Partnership concepts among client countries and World Bank task managers. At the same time, continued progress with the Uganda project will also provide GEF and the World Bank important practical experience on the development of and agreement on operational criteria and common program principles that will be required for future Strategic Partnership projects. These include:

The use of APL performance triggers for release of subsequent tranches based on approval by the WB Regional Vice-President and the GEF CEO. Specific targets for later tranches for projects will be brought into closer focus during project appraisal, but due to the scale and time-frame of APL investments, some uncertainty on the pace of barrier removal and market development will always remain, and a re-assessment of incremental costs will have to be performed as early tranches reach conclusion and transition to the next. It is anticipated that initial Bank Board and GEF Council approval of Strategic Partnership projects will define the basic parameters of projects, permitting management approval on a practical and timely basis. Projects that take a slower than expected pace will simply not proceed to the next tranche. Additional review by Bank management or the GEF Council will only be required when project fundamentals change significantly or were not foreseen in initial project analysis.

Development of comprehensive Monitoring and Evaluation plans specifically tailored to the larger scale of Strategic Partnership projects and some of the uncertainties introduced by multiple APL tranches plans will be required to: a) measure and verify forecasted benefits and impacts; b) guide the release of funding tranches based on performance, and c) promote widespread replication in other markets.

In this (and most future) Strategic Partnership approaches, mainstream financing is expected to cover the bulk of investment costs, and verification of the long-term availability of such funding for long-term and widespread program replication will be expected in the preparation

6 and analysis of Strategic Partnership proposals. As part of barrier removal efforts, the increased initial transaction costs and economic costs of market aggregation may continue to be covered (as they are under current GEF operational procedures) as long as there are prospects for the activity to be economically viable by the end of the intervention. GEF may also help to facilitate the set-up dedicated credit lines, vendor financing, insurance and leasing programs and other mainstream financing mechanisms to enable access to finance. It is expected that GEF’s long term financing role of such projects may include sharing part of perceived technology performance and other risks through contingent financing arrangements (guarantees, loans, contingent grants), particularly in later tranches of programs where initial barrier removal efforts have been successful, and where contingent financing may be useful in facilitating a transition to commercial financing.

Future projects will attempt to more clearly define the use of GEF resources in the context of "holistic" energy interventions and representing a high level of country commitment to promote ‘clean energy’ and simultaneously address other parameters such as energy efficiency, sector policy, etc. as part of the partnership approach.

Other important programmatic modalities envisioned for the Strategic Partnership, such as the use of long-term technology support tactics (such as the Non-fossil Fuel Obligation [NFFO], Energy Feed Law price support, or Renewable Energy Portfolio Standards) will likely be addressed through larger, country-based initiatives (such as the China Renewable Energy Market Expansion Program now being developed). The other specific approach suggested under the initial SP proposal, the Flexible Decision Authority envisioned for use by the International Finance Corporation (IFC), remains the subject of discussions between IFC and the GEF Secretariat.

Proposed Strategic Partnership Operations and Approval Approach

Assessment of APL projects will be based on GEF's usual standards, with each tranche viewed as separate but inter-linked projects. Approvals for continuing GEF support of an APL under the Strategic Partnership are proposed to be based on established procedures of delegated authority to the GEF CEO, and would be based on verification of compliance with agreed performance milestones. Specifically the following steps are proposed: a) Approval of tranche releases would be based on the project meeting minimum accomplishments and trigger points described on an indicative basis in the PCD and in greater detail in the Project Appraisal Document (PAD) developed for each tranche. The World Bank will keep the GEF Secretariat advised through upstream discussions during PAD development, and will provide a programmatic report to the Secretariat at the completion of each tranche. b) GEF approvals will parallel the rolling review process used by the WB for the APL. Based on the PAD approved by the WB Regional Vice-President for proceeding to the next tranche of the APL, the WB would request GEF CEO approval for GEF co-financing. b) On the basis of this information, the GEF CEO will determine the adequacy of accomplishments of the previous tranche and approve release of the next tranche. The CEO and

7 Secretariat may request clarification of performance indicators if required. d) The GEF CEO will provide an information document to Council based on these three elements, indicating to Council that program performance fell within acceptable margins and conformed with minimum indicators expressed (for that tranche), and signalling CEO approval of the next tranche. If there are significant deviations from originally agreed targets, Council would be invited to review the relevant PAD containing specific responses to the changing project circumstances that have caused the deviation before CEO endorsement.

8 A: Program Purpose and Project Development Objective 1. Program purpose and program phasing: (see Annex 1) While Uganda’s economy has consistently registered high economic performance, delivering an average annual increase in per capita income increase of 3.6 percent over the last decade, development in rural areas has lagged well behind urban areas. While the high growth performance has propelled rises in living standards – the population below the poverty line fell from 56 percent in 1992/93 to 44 percent in 1996/97 -- poverty remains pervasive and extensive. Much of Uganda’s rural population has not yet received or seen the benefits of commonplace modern goods and services, and local growth prospects are constrained by a lack of, inter alia, adequate physical infrastructure.

The purpose of the proposed long-term program is to develop Uganda’s rural energy sector so that it makes a due contribution to bringing about rural transformation, i.e., this sector facilitates a significant change in the quality of life of rural households as well as the productivity of rural enterprises. For this to happen, the rural energy sector would have to selectively build and exploit synergies between cross-sectoral assets, recognizing the significant linkages between such assets and therefore between the strategies to building and benefiting from them, (see section B3, Strategic choices), while avoiding unnecessary inter-sectoral linkages that may spread implementation difficulties in one sector to other sectors also.

Uganda is well-endowed with renewable energy resources, whose development could contribute to environmental protection as well as rural transformation, but little progress has been made so far in utilizing these resources (with the notable exception of large-scale hydroelectric power generation on the Nile). The global purpose of the proposed long-term program is to contribute to global environment protection by reducing greenhouse gas emissions; it is expected that the development of renewable energy would also make a significant contribution to rural transformation.

Phasing: It is proposed that the ten-year APL be divided into three tranches, roughly equal in terms of time. At present, Uganda lacks both the capacity and an appropriate institutional framework for the type of commercially oriented rural and renewable energy development envisaged in this APL, and upon which a large-scale program can be built. Hence, the overall approach is that the first phase would start small in terms of investment, while in parallel building the necessary capacity as well as the institutional and policy framework. The pace of investments would pick up in the second and third phases.

The phased approach of an APL provides an effective instrument to ensure that a robust policy and institutional foundation is in place, upon which a large scale program can be built, once the significant risks are dealt with. The phasing strategy to achieve the development objectives of the proposed program is:

First phase: Development of requisite framework and limited investments

The central objective of the first phase is to put in place “on-the-ground” a functioning conducive environment for commercially oriented service delivery and small-scale renewable energy power generation by private enterprises, which can effectively support scale-up of

1 electricity access to underserved areas and on a sustainable basis. The focus would be to mitigate the main barriers, which relate to:

(i) regulation: plug the remaining gaps of a lack of detailed designs and implementation modalities of the applicable rules and procedures, consistent with the Electricity Act of 1999; agreement about this has been already reached with the Government (see section B2b),

(ii) financing: establish efficient and effective intermediation mechanisms for commercial financing (long-term debt, working capital) for private sector enterprises and for transfer of grants (Rural Electrification Fund – see section B2b), and

(iii) technical assistance and capacity building appropriately targeted to the relevant public sector institutions (central and local, including LC5 and LC3 levels), to commercial institutions, and business development services to private sector enterprises, in support of their respective roles in the policy setting, promotion, financing, regulation, service provision, and monitoring/evaluation of commercially-oriented rural electrification (see section B4).

While the above three barriers are also broadly applicable to renewable energy, some additional issues related mainly to renewable energy would also be covered in the first phase. In particular, a specific regulatory issue is the establishment of the contractual framework and rules/obligations for wheeling power over the main rid for third party sales, related pricing, penalties/remedies for non-performance, etc. (see section B2, Government strategy). The technical assistance and capacity building would be in line with the principles of the Global Environment facility (GEF)-World Bank Strategic Partnership for Renewable Energy: (i) develop a strategy and implementation plan for building the capacity of in-country intermediaries to identify, develop, appraise and move towards financial closure renewable energy investments, (ii) prepare a renewable energy resource information collection and dissemination system that provides reliable data that enables interested private sector investors to initiate their own assessment of potential projects; and (iii) activities to help reduce the gap in solar photovoltaic product prices, quality and range by moving Uganda in the direction of international best practices, as applicable to Uganda.

The first phase would start small in terms of investment, treating each sub-project on a case-by-case basis, to test (and refine, as necessary) and prove the readiness of business models and associated support systems for commercially oriented rural electrification and for meeting essential community needs, for scaled-up delivery in subsequent phases. In parallel, the first phase would begin awareness campaigns, especially at the regional (LC3) level about the program’s relevance to the communities and how they can participate.

Finally, the first phase of the APL will provide the opportunity of conducting a few and highly selective pilots with high likelihood of exploiting cross-sectoral synergies, with a view to getting them ready for increasing broader and deeper penetration in subsequent phases.

2 Second phase: Accelerating/building momentum for investment and continuing capacity building

The central objectives of the second phase1 would be to:

(i) accelerate investments and increase the regional coverage by shifting from the case-by-case approach of the first phase to processing sub-projects through the institutional framework, with continuing business development assistance, including making available generic packages, which individual entrepreneurs would tailor to their particular situation, of proven, low-cost technologies, workable financing modalities, and guidelines for community participation/acceptance developed in the first phase,

(ii) fine tune and strengthen the institutional framework in light of any difficulties encountered by sub-project developers, and increase the extent of decentralization in terms of responsibilities for program support and management, monitoring, and expansion,

(iii) Mainstreaming of successful pilots, with any necessary adjustments, undertaken in the first phase, and implement fresh pilots that reflect fresh opportunities as well as the experience with earlier pilots.

The activities specific to renewable energy would follow from those initiated in the first phase, and would consist of building in-country capabilities, resource data dissemination, and continuing dissemination and promotion of international best practices.

Third phase: Rapid scale-up and consolidation of institution build-up

1 At this time, the details of the activities in the second third phases are less sharp than for the first phase, and would be further developed during the course of project preparation as well during the first and second phase of project implementation.

3 The central objective of the third phase would be to shift the focus to exponential growth in investments so as to reach the Government’s long-term targets for rural electrification and renewable energy development, with rural transformation f 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 4444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444

4 555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555 555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555 555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555 555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555 555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555 555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555 555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555 555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555 555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555 555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555 555555555555555555555555555555P)2, which the Bank supports, fully integrates poverty issues in the national development strategy and obviates the need for a separate plan for the poor. The PEAP articulates the Government’s priorities for the purposes of resource allocation, and provides a framework for donors, including Bank support. The PEAP rests on two two key strategies, as follows:

Increasing household income by facilitating rapid and labor-intensive economic expansion by development of requisite economic infrastructure including roads, electricity, rural market infrastructure and provision of rural credit and financial services, and maintenance of an enabling policy framework for private sector and community participation.

Improving the quality of life of the poor through better access and quality of primary health care, water and sanitation, primary education, as well as preserving the environment.

The proposed ERT program is consistent with this strategy.

1b. GEF Operational Program addressed by the project:

The proposed project is one of the first to be proposed under the newly-established GEF/World Bank Strategic Partnership for Renewable Energy. The project is fully consistent with the GEF Operational Program 6: Promoting renewable energy by removing barriers and reducing implementation costs.

2. Main sector issues and Government strategy: Uganda faces three primary challenges in the energy sector.

2a. Power sector reforms and capacity additions on the main grid

Poor performance of power sector. At present, the power sector’s performance is poor. The Uganda Electricity Board (UEB),3 which no longer has a legal monopoly in the power sector 2 The Government, with the Bank’s assistance, is currently revising the PEAP. It is expected that the revised PEAP will constitute the Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP) for Uganda. 3 UEB was established in 1948 as an independent institution charged with the responsibility to generate, transmit, distribute and supply electricity within Uganda and other countries in the region. UEB is a public

5 after the enactment of the Electricity Act of 1999, still continues to undertake generation, transmission and distribution activities in the country4. UEB suffers from poor financial performance, operating inefficiency, low productivity and inadequate funds for required investments.

By normal standards, UEB is close to insolvency. It has not been able to generate an adequate cash flow from its present average retail tariff of about 6.7 ¢/kWh. In 1998, it billed the equivalent of about $64 million for electricity consumption, but collected only $38 million.

Uganda is experiencing daily power shortages of around 80 MW, which is significant, given Uganda’s main grid installed capacity of about 180 MW. System losses, both technical and non-technical are currently estimated at around 35%. Poor collection is also a concern since revenues are collected on about 80% of electricity billed. This results in UEB realizing only around 50% of the value of all electricity generated in the system. UEB’s accounts receivables are currently equivalent to about nine months’ billings, but with 50% being due for more than one year. Though being addressed by the new management team, non-technical (or commercial) losses due to illegal connections and non-payment of utility bills continue to remain serious problems. Various factors such as an inadequate billing system inaccuracies and the existence of unmetered supply have exacerbated the problem. The public sector, which consumes roughly about 10% of the electricity, is a significant defaulter on its payment obligations to UEB.

Ongoing and planned reform efforts. The Government has embarked on a reform program for the sector which includes: (i) establishing new electricity legislation and an independent regulatory regime to promote a commercially oriented private sector-operated industry structure, (ii) unbundling generation, transmission and distribution activities, and (iii) creating incentives for competition and private sector investment. The reform program has been motivated by the critical need to improve the performance of the power sector and attract much needed investment.

In February 1999, the Bank Group brought together key decision-makers within the Government and its advisers to discuss the need for progress on implementing a comprehensive sector reform program5.

enterprise 100% owned by the Government of the Republic of Uganda, and is funded by government equity, debt and accumulated reserves. Its policies are determined by the Board of Directors, who are appointed by the Minister of Energy and Mineral Development. The day to day running of UEB is executed by the Managing Director (the chief executive officer) together with a management team appointed by the Board of Directors 4 These include the 180 MW Owen Falls Power Station and the 1 MW Maziba hydro power station, some isolated diesels, an interconnected 132 kV and 66 kV transmission network, a 33 kV sub-transmission network, and a distribution network at voltages of 11 kV and below. 5 This was done as part of the effort to support the IFC-sponsored Bujagali project.

6 Reform Event Reform Event: Revised Target Review London Economics Study & agree with WBG on Reform Agenda April 1999 (actual) Cabinet Approval of the Reform Agenda June 1999 (actual) Parliamentary Approval of Legal / Regulatory Framework (i.e., Electricity November 1999 (actual) Law) Hiring of Privatization Consultants February 2000 Appointment of Regulator April 2000 Request for Proposal for Privatization of Distribution October 2000 Successful Awarding of Concession for the Privatization of Distribution April 2001 Successful Private Sector operations in Distribution July 2001

Capacity additions. The UEB grid-connected electricity generation capacity is currently around 183 MW generating roughly 1,200 GWh. Most of this generation is through the 45-year old Owen Falls hydroelectric plant on the Victoria Nile with additional generation from a 1 MW hydro power station at Maziba and isolated diesel generators. The on-going Power III project provides for the civil works for Units 11 through 15 and 80MW (Units 11 & 12) generating capacity at the Owen Falls Extension facility which is expected to be commissioned in mid-2000 (total estimated cost of around $280 million). At the completion of the Power III project, based on reasonable long-term system planning expectations, both Owen Falls facilities together are expected to generate on an average around 240 MW of power and 1,600 GWh of energy. NORAD and SIDA are financing Unit 13 (40 MW) at the Owen Falls Extension. This unit is under construction and will be commissioned by end-2000.

The Government has expressed interest in an IDA-financed Power IV project under which one or two additional turbines (Units 14 and/or 15) would be installed at Owen Falls Extension. This would provide a further 40-80MW installed capacity that could be commissioned by end-2002, at the earliest. Under a run-of-river operation regime, the usefulness of Unit 14 has been established, while studies are underway for Unit 15.

The proposed Bujagali project would add an installed capacity of 200MW (with the option of an additional 50MW); upon commissioning, the Bujagali project will almost double the size of Uganda’s generation capacity. In view of the likelihood that there may be surplus generation capacity when Bujugali comes online, the Government is looking to secure additional electricity sales through incremental exports6 to Kenya and Tanzania. While the incremental 6 UEB currently exports 30 MW to Kenya, 7 MW to Tanzania and 1 MW to Rwanda. The Kenya power export contract (Kenya-Uganda Electricity Agreement) expired in mid-October 1999. However, exports have continued under the now-lapsed contract terms and a new export arrangement is expected to be completed soon. The Kenyan export sales contract provided for a guaranteed minimum supply of 10 MW during the ‘Day’ (5 AM to 6 PM) and a guaranteed minimum of 30 MW at ‘Night’ (11 PM to 5 AM) to Kenya. No supply was guaranteed

7 exports to Kenya will not require additional transmission infrastructure, exports to Tanzania will require a 300 km high-voltage transmission line; the concession to build this transmission line has already been awarded to an Ugandan entity that in turn has had preliminary discussions with AfDB on potential financing.

The table below summarizes the existing and planned generation expansion options in Uganda, and compares the installed capacity with estimated domestic requirements at the time of commissioning.

Planned Generation Expansion Options – Domestic Requirements Total Surplus/(Deficit) Project Source Year MW Sub-Total Low Base Existing Owen Falls + isolated 1999 183 (93) (93) Power III Owen Falls Extension 2000 80 Norad/Sida Owen Falls Extension 2000 40 303 (13) (87) Power IV + Bujagali Power IV Owen Falls Extension 2002 40* 343 (16) (74) Bujagali Bujagali Project 2005 200 543 119 18 * Unit 14 (40 MW) only.

2b. Low rural access to electricity. In Uganda today, with a population of about 22.6 million, an estimated 4.5 million households out of a total of about 4.7 million, remain “in the dark,” without access to electricity. The overwhelming majority of these unserved households are in the rural areas. Only an estimated 5% of the total population – and less than 1 percent of the rural population -- has access to grid supplied electricity; Uganda currently has one of the lowest per capita electricity consumption (44 kWh/year) in the world (India 300, China 580, USA 11,000 in 1996). About 72% of the total grid supplied electricity is consumed by 12% of the domestic population concentrated in the Kampala metropolitan area, and in the nearby towns of Entebbe and Jinja.

Adverse impact of poor performance and limited access Adverse impact of poor performance and limited access. Recent surveys indicate that the quality and adequacy of power supply is the perceived by urban enterprise managers as the most binding constraint to private investment.7 The rural areas are also seriously constrained by the lack of access to electricity; sustainable rural development and the accompanying benefits of increases in living standards will not occur without the provision of modern energy forms, and specially electricity. Yet, most rural households have little hope of getting such access, and even rural public institutions such as health and educational facilities are unable to provide essential services due to a lack of electricity.

Macro-economic growth is being seriously constrained. As Uganda is predominantly rural, rural and off-farm activities, led by small and medium enterprises, will have to be one of during peak hours (6 PM to 11 PM). Presently the bulk export tariffs to Kenya during the Day and Night are ¢8/kWh and ¢6/kWh, respectively. The governments of Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda envisage a partnership within the context of East African Co-operation for the development of electricity generation and transmission projects which is likely to further increase exports from Uganda. In total Uganda presently exports about 300 GWh with total export earnings in the order of $18-20 million, annually.

7 Reinikka, R. and J. Svennson, How Inadequate Provision of Public Infrastructure and Service Affects Private Investment, December 1999, World Bank , Policy Research Working Paper Number 2262. The survey revealed that in 1998 Ugandan private firms incurred on average about 89 days of power outages per year; as a result, as many as 77 percent of large firms, 4 percent of medium-sized firms, and 16 percent of small-sized firms owned back-up power generation facilities.

8 the main engines of rapid and broad-based economic growth. Yet, today, this potential growth is being seriously constrained by the lack of adequate investment for the provision of rural infrastructure services, of which electricity is a key component. This undermining of the growth potential of rural small and medium businesses and entrepreneurs directly constrains the generation of rural jobs and income.

Need for a paradigm shift.

Limited future impact of a restructured Uganda Electricity Board (UEB) in rural areas. UEB today has well under 200,000 customers, the majority of whom, about 128,000, are in the urban areas. At present, UEB connects well under an additional 10,000 customers per year, which implies that Uganda is losing the access race, as population growth at the rate of 2% per year which would add 90,000 or more new households per year.

Even under the best of circumstances, with a restructured UEB and its revitalized off- springs, as per present draft proposals for power sector restructuring and reform, the rural access picture is unlikely to improve perceptibly. For instance, under the optimistic assumption that the number of rural households connected to the main grid would increase at a sustained, compound annual growth rate of 15% over 2001-2010, the total number of rural households connected to the main grid would increase from about 30,000 in 2001 to about 125,000 in 2010. This would imply a rural access rate of about 3% based on the current rural population, and much lower once population growth and otherdomographic demographic changes are taken into account.

Need for a paradigm shift. The irony is that by various indicators of revealed preference, a substantial segment of the unserved rural firms and households are willing and able to pay significant sums for electricity. Some rural businesses have resorted to self-provision of electricity, at a unit cost that is far higher than would prevail in an organized, commercial delivery system. Most rural businesses and households simply make do without electricity or have devised make-shift arrangements, which are vastly inferior substitutes for electricity, again at high unit costs. It follows that a paradigm shift in the organization and approach used hitherto in rural electrification is needed to meet Uganda’s aspirations for off-farm led economic growth along with increases in the rural living standards.

Government strategy. The government has adopted, in consultation with the Bank, a commercially-oriented approach -- with the government playing the role of a market enabler -- towards rural electrification. A Rural Electrification Strategy Paper is currently under preparation by the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development, and scheduled for submission to the Cabinet shortly. The main elements of this strategy are:

(i) Level playing field for private sector participants. This implies a market/sector structure that will:

. Permit private sector entry for supply of electricity – generation, transmission, distribution/retailing – from the interconnected grid system as well as stand-alone, independent mini-grid systems. (Already provided for in the Electricity Act of 1999).

9 . Ensure fair competition for all suppliers with respect to UEB and its successors, in particular, all necessary steps will be taken to ensure that UEB does not have an unfair advantage over potential private sector participants in competing for distribution/retailing of electricity purchased in bulk from the UEB-operated grid system. (To be implemented as part of power sector reforms).

(ii) Enabling regulatory framework. There is a need for a suitable regulatory framework that has:

. Clear separation of responsibilities of: (i) planning, monitoring, policy setting, licensing and permits, establishing/promulgating regulations, (ii) compliance (“regulator”), and (iii) conflict/resolution, arbitration, and adjudication in cases where an involved party wishes to appeal a finding of the regulator. (Already provided for in the Electricity Act of 1999)

. “Light-handed regulation” procedures and processes for small, stand-alone grid- based power system systems. (Already provided for in the Electricity Act of 1999, with details still to be developed).

(iii) Cost recovery and cost-based tariffs, to facilitate private entry and local initiatives, recognizing that this will imply that consumers in different parts of the country will pay different retail tariffs, and that the tariffs for some consumers will be significantly higher than for others, even after subsidies (see below) have been provided for. In particular, there is a need for:

. Regionally differentiated retail tariffs, for all suppliers, including UEB and its successors, which vary according to the cost of service delivery. Further, the benefits of the low-cost, big hydropower resources will be allocated on a national basis, and not restricted to main grid consumers only. (Already provided for in the Electricity Act of 1999, with details still to be developed)

. Bulk-supply tariffs based upon the cost of supply at the delivery point in the main grid system. (Already provided for in the Electricity Act of 1999, with details still to be developed)

. Non-discriminatory wheeling tariff (and access) to facilitate power transactions between distribution concessionaires and third-party generators. (Already provided for in the Electricity Act of 1999, with details still to be developed)

(iv) Subsidy transfer and financing mechanism, i.e., a Rural Electrification Fund to take account of regional and other considerations, with due consideration to efficiency and sustainability under a regime of cost-based regionally-differentiated tariffs and multiple service providers in the future. In particular, the Government will design subsidy schemes and allocation procedures that:

. Follow pre-established clear, explicit rules that

10 Are transparent, i.e., avoid implicit (and operating) subsidies that frequently lead to waste and non-accountability.

Are linked to results, i.e., maintain the focus on expanding access by subsidizing the initial cost of investment rather than the cost of operation.

Provide strong cost-minimization incentives, i.e., retain the commercial orientation to reduce costs even though subsidies are being provided.

. Ensure good governance, i.e., the institutional responsibility for policy and rule setting for the REF will be clearly separated from the administration of the Fund, and an independent entity will be responsible for requisite checks and balances, monitoring performance, and ensuring compliance. (Already provided for in the Electricity Act of 1999, but some key changes are required – see section C2).

2c. Renewable energy resource potential is under-utilized. Apart from large-scale hydropower schemes, only a small fraction of Uganda’s renewable energy resource potential – which includes (i) power generation from a variety of sources such as biomass residues, small hydro, wind, and geothermal and (ii) solar energy for stand-alone photovoltaic systems – has been tapped to date. While several small/mini-hydro and biomass projects have been proposed in the past several years, their development has been constrained by a number of factors including: i) a widely held belief that only UEB was permitted to sell power; ii) lack of access to long-term financing; iii) undeveloped local capacity for planning and implementing such projects. The prospects of utilizing solar energy have been given a boost by the ongoing UNDP-GEF Uganda Pilot Project for Photovoltaic Rural Electrification.

Government strategy. The government has adopted, in consultation with the Bank, a strategy to establish a regulatory and investment climate within Uganda that promotes private sector led, commercially-oriented development of these resources. In addition, the Government will seek financial support from various multilateral, primarily GEF and Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) sources, and bilateral agencies that are interested in supporting renewable energy.

3. Sector issues to be addressed by the project and strategic choices: The two sector issues to be directly addressed by the project are the low rural electricity access and the under-utilization of the renewable energy resource potential. In general, the key design features and details of this project would be coordinated with the activities and policies related to power sector reforms and capacity additions; in particular, there are three links that would have to be closely coordinated:

UEB operates several isolated systems in rural areas, based on local generation, that are not connected to the main grid. Many of these systems are unlikely to be attractive to potential private sector firms that would otherwise be interested in becoming distribution concessionaires, once the restructuring of UEB is complete. Hence, the disposition of these rural UEB assets and the continued provision of power in these areas will be coordinated with the overall sector reform process.

11 The addition of any renewable energy based power generation capacity on the main grid would be coordinated with the overall planned capacity expansion plan. In particular, while there is a generation capacity shortage at present, this may turn into a surplus when Bujugali comes online, and any capacity additions must take account of this.

The design and details of the Rural Electrification Fund (REF) would be coordinated with the overall sector reform process, for two reasons. One, some of the resources for the REF would come from levies imposed on the main grid. Second, it is vital to have a clear and transparent specification of the geographical areas that would qualify for subsidies from the REF.

Strategic choices. The first strategic choice made by this project is to stretch the project’s boundaries to focus on rural transformation, rather than the energy sector itself, and, further, set ambitious targets within this context. In particular, the proposed project will establish links with (i) physical capital, via investment sectors, such as telecommunications/computers/Internet,8 water9, and small and medium enterprises (see section D3, Lessons learned), and (ii) human capital, via social sectors such as health (see below) and education to enhance the quality and effectiveness of their service delivery. The basis for these links will be their need for and efficient use of adequate and reliable supplies of energy; most of these links will be tested in the form of pilots in the first phase of the APL. The alternative of a less ambitious, internally-focused rural electrification project does not offer good prospects of a significant development impact, at a time when it is clear that, in the past, even successful projects, particularly rural electrification projects10, have often failed to make a noticeable difference in rural lives. For instance, while it will take a considerable, sustained effort on a number of fronts to reach the project’s targets, they are not ambitious to the extent that at the end of the project, the vast majority of the rural population would still be left without the benefits of electricity.

8 An initial field visit in which a telecommunications mission joined the project team has already led to plans to establish a Multipurpose Community Telecenter (MCT) -- at Kisizi (see Annex 3) where expanded power supply is proposed to be made available under this project -- that would provide communications, information, multimedia, and computing functions at a common center to help address a variety of community problems and needs. Given the urgent needs of this community for improved communications, immediate steps are being undertaken to integrate this site into the larger satellite-based communications network being piloted by the Ministry of Education in cooperation with the World Links for Development Program, as well as a range of potential international and private sector partners. The plans are that the grant-financed pilot MCT would become operational independent of and even prior to the finalization of this project. Based on the experience with this and another pilot in the first phase, a strategy for scale-up and implementation would be developed. 9 Discussions have been initiated with the proponents of a successful Development Marketplace 2000 proposal related to a low-cost method of disinfecting water at the household level in rural areas; this method requires a reliable power supply. The proposal includes a pilot in Latin America; it is now being explored whether a pilot (based on this and/or other suitable technologies) could be tested in Uganda. This would fit in well with one if the findings of the Uganda Participatory Poverty Assessment: “In discussions concerning water, local people focused predominantly on the need for clean drinking water for people and livestock, although rivers, lakes and swamps were also seen as important.”

10 “The overall record of rural electrification (R.E.) has been satisfactory. Nevertheless, the reestimated economic returns have proven considerably lower than planned and a whole range of expected indirect and external benefits have not materialized, especially with respect to industrial growth.” Rural Electrification in Asia: A Review of Bank Experience, OED, World Bank, June 30, 1994, Report No. 13291.

12 A second strategic choice is to promote rural electrification in a commercially-oriented manner, under which the investment, operational and consumption decisions at the margin -- “the last dollar”-- are made on an unsubsidized basis, while affordability and equity considerations are tackled by an appropriate subsidy transfer and financing mechanism (see section B2b, points (iii) and (iv) of Government strategy). This is the only option that offers good prospects of meeting the project’s targets. The alternative of State-led rural electrification with subsidies provided through a national uniform tariff has proved to be non-workable in most countries, and is a non-starter in Uganda, given UEB’s poor past and current performance. On the other hand, the option of totally commercial rural electrification, i.e., with no subsidies, would be unlikely to attract potential service providers, given the risks and high initial costs arising from the lack of any experience with such an endeavor, and would be unlikely to accelerate rural electricity access significantly, given the limited affordability.

A third strategic choice is neutrality and flexibility with respect to regional location, business models, supply modalities and technology. In particular, the project will be national in scope, support multiple business models, including public-private joint ventures, and utilize a broad set of supply options, ranging from relatively large (for rural areas) stand-alone mini-grids to small solar photovoltaic systems11. While this does increase the complexity of project design and implementation, a narrower range of supply options would be unlikely to accelerate and scale-up rural electricity access, thus reducing the impact of the project. At the same time, the project’s approach will be to look for and define workable entry points and growth trajectories for each option in order to mitigate implementation difficulties. A fourth strategic choice is to explicitly focus on the needs of rural enterprises and public institutions, and not just on rural households. In particular, the program would determine, in conjunction with health and education sector authorities, the energy needs, as well as the priority attached to them, of rural health and educational facilities, and formulate plans to meet them in a cost-effective manner, so that the poorer segments of the rural population are able to receive some indirect benefits from this program. For instance, in Uganda, rural trading centers (see below) include clusters of enterprises, many of which wish to improve their productivity, that have an ability to pay significant amounts for electricity, and can form the critical mass of demand required for setting up an independent grid, which could then serve nearby households and public institutions on relatively affordable terms.

11 While the program will not directly support battery-charging stations to serve individual household who use automotive batteries to power some lights and/or radio/TV, it is expected that such enterprises will spring up around trading centers and other clusters that become electrified.

13 In most cases, rural public institutions would be unable to pay the full cost of energy supplies; particularly, the user fees they collect are often inadequate to cover even their essential operating costs. At the same time, the commercial orientation of this program requires that the energy providers recover their costs, and do not provide energy to any consumers at reduced prices with implicit cross-subsidies. This “affordability gap” would be covered by devising sustainable financing plans consisting of local contributions, government funds, and grant support from bilateral donors.

An unelectrified trading center in Uganda; the bulk of Uganda’s estimated 2,000 trading centers – whose numbers are rising with economic growth – are unelectrified.

A fifth strategic choice adopted by this project is to work in partnership with other donors. This is not only consistent with the Comprehensive Development Framework (CDF) approach but also has particular relevance for Uganda, where bilateral and multilateral donors have been and are planning to provide significant support to the energy sector, including for rural electrification. The alternative arrangement of the Bank and the donors functioning essentially independently of each other, even with some amount of coordination, offers little beyond a slowly evolving status quo with limited development impact.

A sixth strategic choice is to promote rural energy and renewable energy in tandem. While it is possible, in principle, to separate the two12, in Uganda there are significant linkages between renewable energy and rural transformation. To start with, the promotion of solar photovoltaic systems for rural areas is now a well-established practice in projects sponsored by the Bank as well as other agencies, and in Uganda, the ongoing UNDP-GEF project has already made a start in this direction. Further, many rural areas of Uganda have mini-hydro, coffee hulls, wind and other renewable resources that could be used to generate the power for independent mini-grid systems. The proposed project is expected to be one of the first under (i) the GEF/World Bank Renewable Energy Strategic Partnership, under which GEF would use the APL instrument, and (ii) Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) sources as international trade in greenhouse gas emissions develops.

Finally, the project’s activities will be coordinated with the national strategy to combat HIV/AIDS, which is now viewed as a national problem, and not just as a health sector problem. Discussions have been initiated with the Ministry of Health and the National AIDS Commission regarding the manner in which this project, which is expected to have a significant rural outreach, can serve as an agent of the

12 This separation has been done in some of the Bank’s projects in Asia.

14 national HIV/AIDS strategy. At this point, apart from the strengthening of rural health and educational facilities by providing them with energy services, there appear to be two channels for cooperation. First, the project teams could act as the “arms/legs and eyes/ears” for the national strategy13, spreading the messages and materials provided by the national authorities during the course of meetings and discussions in the rural areas as well as at headquarters, while providing feedback about reactions and suggestions. Second, the service providers participating in this project could as act as channels for disseminating HIV/AIDS materials provided by the national authorities.

Risk implication of strategic choices. A risk implication of these strategic choices is that the proposed project may be too large and too complex, given Uganda’s limited absorptive capacity, particularly in this sector, and may face above-average implementation problems and delays for the project. This issue is discussed later in section F Sustainability and Risks.

4. Program description and performance triggers for subsequent loans:

The program will consist of two broad components: capacity building/technical assistance and investment.

The overall objective of the capacity building/technical assistance component will be the creation and/or strengthening of the organizations and institutions involved in the implementation of the project to operate these facilities and resources in a sustainable manner, beyond project completion. The capacity areas covered would be the policy setting, promotion, financing, regulation, service provision, and monitoring/evaluation of commercially-oriented rural electrification and renewable energy development; the agencies covered would include central and local authorities, private sector enterprises, including rural small and medium enterprises, and NGOs/CBOs.

To this end, while the project will make full use of national resources and strengthen them as necessary, it is also recognized that external financial and human resources would also have a key role to play in this component, particularly in the first two phases of the APL, within the framework of a long-term capacity development plan that will serve as an operational roadmap for sustainability. The scope and magnitude of this component will be determined by: (i) an overall assessment of capacity needs, and (ii) formulation of the overall approach of the capacity building plan; these activities will be initiated during pre-appraisal and which will determine the scope and magnitude of investments for this purpose. These efforts will take account of the concepts embodied in the rapidly growing literature related to social capital theory, which will be particularly relevant in the context of increased networking and transparency within the communities benefiting from the project, and on account of the links between the communities and the outside world by way of communication and information.

The capacity assessment will be instrumental in setting the scope, objectives and targets for capacity development. It will indicate what benchmarks are to be used in planning the strengthening of institutional capacities and what level of resources (including TA) are required

13 An initial effort on this account by mission members did not encounter any negative reactions or resistance. Further, the management of one of the sugar mills planning to participate in the ERT program accepted the suggestion enthusiastically, and is planning to display official HIV/AIDS posters in not only the participating sugar mill but also all other facilities that they manage.

15 to attain such benchmarks. These would specified in the context of local management implementation plans, to be developed by the producers, regulators, managers and users of the new energy sources. The monitoring and evaluation plan will also assess cross-sectoral outcomes and synergies resulting from the availability of new services ( e.g. health, education, training, income generation , etc).

The preliminary indications, based on field visits by Bank energy sector missions, are that:

Some of the technical assistance would take the form of introducing and mainstreaming suitable international best practices, particularly those that would reduce the cost of service provision and improving the quality of service offered;

A significant effort is required to increase the capacity of district and lower level authorities, particularly with respect to “light-handed” regulation and promotion of this project, and that these activities should be coordinated with other planned or ongoing district-level capacity building programs.

There will a specific focus on capacity building for renewable energy, as called for in the GEF/World Bank Strategic Partnership for Renewable Energy.

The investment program would consist of four sub-components:

Sub-component 1: Main grid related power distribution and generation. The power distribution would be to presently unserved rural areas that would be connected to the main grid, with the power supply to come from the large-scale hydropower plants. It is expected that the private sector distribution concession areas, arising from sector reforms, would be narrowly defined in terms of the physical distance from the existing grid. Thus, the extension of the main grid to rural areas and the consumers would be supported under this sub- component. In keeping with the objective of renewable energy development, there would be additional power generation from small, renewable energy resources, such as sugar mills, that are close, or already connected, to the main grid. In the long run, the sale of this power would be to third-party customers via wheeling through the main grid, i.e., in the long run, there would be no power purchase agreement between the generator and the main grid, which would merely serve, for a fee, as the “highway” over which power is transported from the generator to a third-party customer. However, in the short run until the Bujugali project comes online, there would likely be a power purchase agreement between the main grid and the renewable energy power generators; further, after Bujugali comes online, there would likely be a transition period during which the renewable energy generators would have some assurance of the sales of their power, after which the long run wheeling mechanism would be utilized.

Sub-component 2: Independent grid systems for relatively concentrated isolated areas with a potential for the use of electricity by rural enterprises. This sub-component would support relatively larger systems that may require some transmission (such as in the West Nile region) and smaller systems, such as those located in rural trading centers, that require only generation and distribution facilities. It is expected that a significant part of the power generation would be

16 from renewable energy resources.

Sub-component 3: Individual/institutional solar PV systems, for relatively dispersed areas where even small independent grid systems are not viable.

Sub-component 4: Pilots for scale up in later tranches. In the first phase, this would include: (i) energy efficiency in use of traditional woodfuels by rural SMEs and public institutions for which a pilot would be prepared in conjunction with ongoing research sponsored by the U.K. Department for International Development (DFID), (ii) provision of telecommunications and connectivity, for which one pilot may be implemented outside this project, and one within the first tranche of this project, and (iii) low-cost household water disinfecting, which requires adequate supplies of electricity, based on a winning proposal in the Development Marketplace 2000 and/or other similar technologies.

The first tranche of the APL would include investments in all of the above sub-components. The various sub-projects identified so far on a preliminary basis for inclusion in the first tranche are described in Annex 3.

Triggers for Phase II

The overall approach is that the triggers for Phase II would be linked to the accomplishment of the objectives of Phase I (see section A1). The triggers, with the details to be developed during project preparation, would be based on (GEF related triggers are presented in italics):