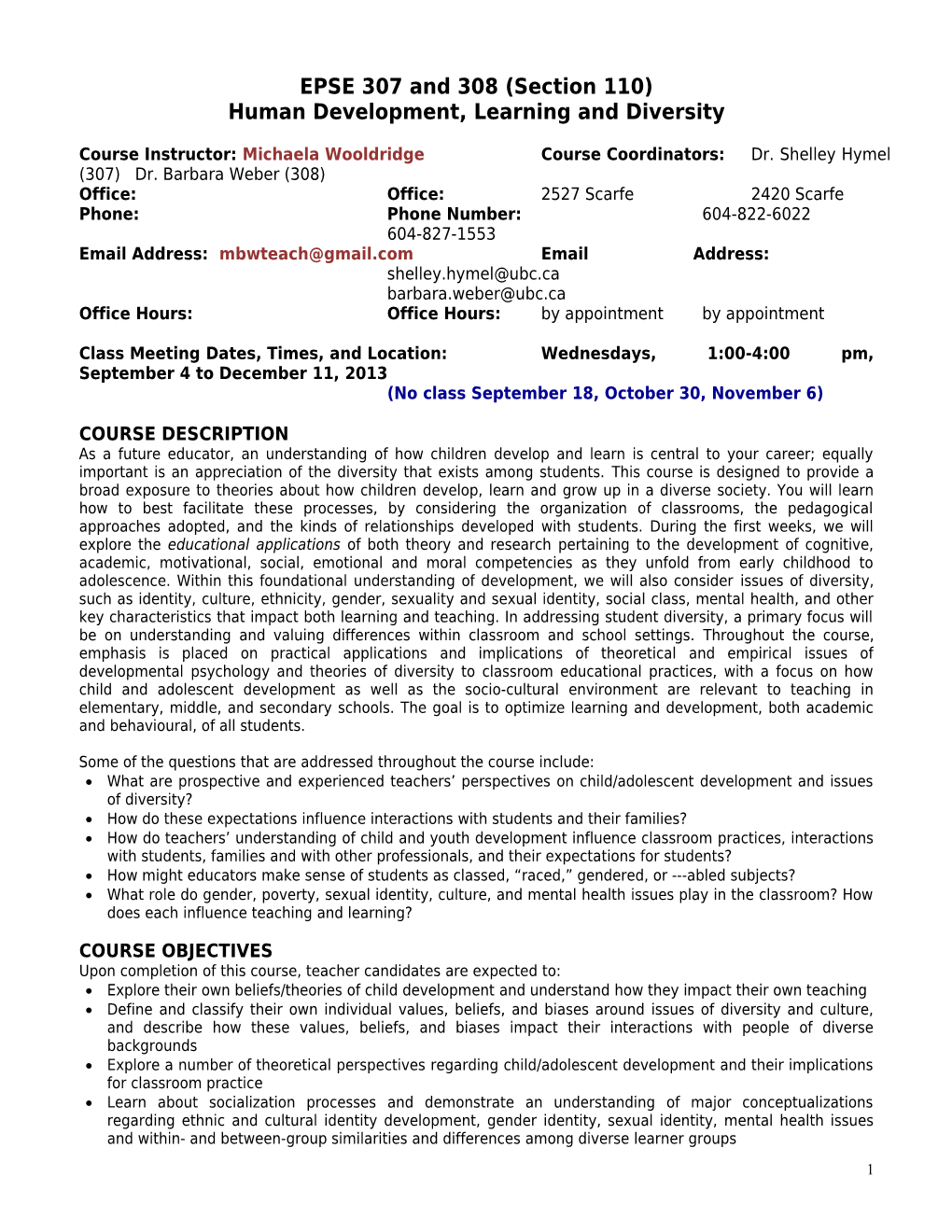

EPSE 307 and 308 (Section 110) Human Development, Learning and Diversity

Course Instructor: Michaela Wooldridge Course Coordinators: Dr. Shelley Hymel (307) Dr. Barbara Weber (308) Office: Office: 2527 Scarfe 2420 Scarfe Phone: Phone Number: 604-822-6022 604-827-1553 Email Address: [email protected] Email Address: [email protected] [email protected] Office Hours: Office Hours: by appointment by appointment

Class Meeting Dates, Times, and Location: Wednesdays, 1:00-4:00 pm, September 4 to December 11, 2013 (No class September 18, October 30, November 6)

COURSE DESCRIPTION As a future educator, an understanding of how children develop and learn is central to your career; equally important is an appreciation of the diversity that exists among students. This course is designed to provide a broad exposure to theories about how children develop, learn and grow up in a diverse society. You will learn how to best facilitate these processes, by considering the organization of classrooms, the pedagogical approaches adopted, and the kinds of relationships developed with students. During the first weeks, we will explore the educational applications of both theory and research pertaining to the development of cognitive, academic, motivational, social, emotional and moral competencies as they unfold from early childhood to adolescence. Within this foundational understanding of development, we will also consider issues of diversity, such as identity, culture, ethnicity, gender, sexuality and sexual identity, social class, mental health, and other key characteristics that impact both learning and teaching. In addressing student diversity, a primary focus will be on understanding and valuing differences within classroom and school settings. Throughout the course, emphasis is placed on practical applications and implications of theoretical and empirical issues of developmental psychology and theories of diversity to classroom educational practices, with a focus on how child and adolescent development as well as the socio-cultural environment are relevant to teaching in elementary, middle, and secondary schools. The goal is to optimize learning and development, both academic and behavioural, of all students.

Some of the questions that are addressed throughout the course include: What are prospective and experienced teachers’ perspectives on child/adolescent development and issues of diversity? How do these expectations influence interactions with students and their families? How do teachers’ understanding of child and youth development influence classroom practices, interactions with students, families and with other professionals, and their expectations for students? How might educators make sense of students as classed, “raced,” gendered, or ---abled subjects? What role do gender, poverty, sexual identity, culture, and mental health issues play in the classroom? How does each influence teaching and learning?

COURSE OBJECTIVES Upon completion of this course, teacher candidates are expected to: Explore their own beliefs/theories of child development and understand how they impact their own teaching Define and classify their own individual values, beliefs, and biases around issues of diversity and culture, and describe how these values, beliefs, and biases impact their interactions with people of diverse backgrounds Explore a number of theoretical perspectives regarding child/adolescent development and their implications for classroom practice Learn about socialization processes and demonstrate an understanding of major conceptualizations regarding ethnic and cultural identity development, gender identity, sexual identity, mental health issues and within- and between-group similarities and differences among diverse learner groups 1 Learn about theories of motivation and how to enhance student engagement, self-regulation, and intrinsic motivation in order to create generations of lifelong learners Learn strategies and approaches for promoting students’ social-emotional and academic success within a diverse society Demonstrate an understanding of major models of cultural sensitivity and ways in which to effectively communicate with students, parents, and colleagues with diverse backgrounds different from one’s own Apply these conceptual models to self, fellow educators, students, and families to foster understanding of the impact of diversity issues on our lives

This course contributes to the attainment of the British Columbia College of Teachers standard #3: Educators understand and apply knowledge of student growth and development.

COURSE UNIT VALUE 3 Credits, 12 Modules

COURSE MATERIALS: Specialized Course Text and Reading package available through UBC Bookstore

Textbook chapters taken from: Woolfolk, A. & Perry, N.E. (2012). Child and Adolescent Development. Pearson. McDevitt, T.M. & Ormrod, J.E. (2013). Child Development and Education. Pearson.

EXPECTATIONS AND ASSIGNMENTS

1. Attendance and Participation

Attendance and participation are essential to the experiential learning that is necessary within a professional pr ogram. Keeping up with assigned readings and participation in class activities and both large and sm all group discussions forms the basis of professional inquiry and development. Therefore, teacher can didates are expected to attend all scheduled classes, lectures and/or seminars. Teacher candidates w ho miss a significant amount of class time (more than 15% of course hours) may be required to repea t the course. If you are going to be absent, please inform the instructor by e-mail, by phone or in writi ng within 24 hours of the missed class. More than one missed class will require a doctor’s note. If a s tudent misses more than one class, the instructor must inform the Teacher Education Office and the t eacher candidate may be asked to repeat the course. Full details regarding attendance are described in the BEd Program Handbook found at: http://teach.educ.ubc.ca/publications/index.html.

Participation also includes that you will submit brief reflections on readings, and prepare to facilitate class discus sions when readings are shared among the students. Reading reflections will be one page maximum i n length following the “Quote, Reflection, Question” format, and will be submitted online prior to clas s. When facilitating class discussions, you you are expected to critically reflect on, respond to, and en gage your colleagues in a discussion of one of several topics or readings (TBA). Facilitation of class di scussions include (a) explaining very briefly the main thesis or premise of the text or theory, (b) givin g one or two examples of the relationships that can you establish between this article/theory and you r own experiences attending school or your current practicum experience and (c) developing 2-3 que stions that you would like to discuss with the group. The main focus should be on creating a critical p erspective that engages your colleagues in a whole class discussion and deep reflection, which will m ake the reading/theory meaningful for your practice as a future teacher.

2. “Theory to Practice” Project: Creating Developmentally Appropriate Lessons ( 30 % of final mark)

Following from our exploration of theories of learning and the development of intelligence, cognitive and academic competencies, you are asked to create a developmentally-appropriate lesson plan with an engaging activity that can be utilized in a classroom. The focus of the lesson plan is up to you, but the lesson plan must be designed for a particular grade level and grounded in developmental principles as addressed in the first segment of this course.

2 Specifically, your task is to develop a lesson plan that you think would provide an appropriate learning experience for students at a particular age or grade level. The description of your plan must be specific enough for other people to reproduce your activity, so please keep in mind that you are writing for a “naïve reader” (think substitute teacher) who likely does not have the same background as you and may require more information in order to understand the goals and activities you have identified for your lesson. Importantly, for this course, you will also need to provide a theoretical rationale for how your lesson maximizes student learning at this particular age/grade, using developmental theories and concepts covered during the course. Your ability to consider multiple theories or aspects of development is needed for top marks. The lesson plan should include at least three parts:

(a) Identify the grade level or age targeted for this lesson and identify the focus, content, and objectives you hope to accomplish and what you expect students will learn, (b) Describe the activities planned and your anticipated goals, and what you will do to help students reach these objectives, based on your understanding of developmental theory/research, and (c) Provide an addendum to the lesson plan that specifies the theoretical rationale for your decisions about both what you decided to teach and how you decided to teach.

Your lesson plan should be about 1-2 pages (Times New Roman, single-spaced, 12-point font) and is due on October 23, 2013.

3. Practicum Observation ( 30 % of final mark)

Attending the 2-week Practicum provides an excellent opportunity to observe and study concrete cases of children’s developmental needs and learning processes (e.g., motivation, intelligence, social-emotional needs, cognitive, emotional and moral development). You will also experience the complex problems, misunderstandings, but also positive opportunities that can arise from diversity in the classroom (e.g., gender, sexual identity, culture, race, poverty, mental health). For this assignment, you will use those experiences for deeper reflection. This assignment is designed as an initial effort to apply the theories that you learn in this class to the educational practices that you observe. You will be asked to choose one topic or focus from this course and follow a set of guidelines for your observation during the two weeks of practicum.

In the observation guidelines you will be asked to: a. Describe exactly what you observed (participants, situation, circumstances, location and time, emotional quality, etc.), b. Describe how this was handled by the other children and/or the classroom teacher, c. Analyze how the incident can be considered in terms of a theory that you learned during the class and reflect on whether or not you/another person reacted as the theory suggested: How did the situation actually played out (what did the teacher or the other children do)? How might you have reacted differently? d. Reflect upon what the theory didn’t talk about or answer, or whether (in retrospect) other theoretical considerations were warranted or might have been more applicable or useful and why. e. Elaborate on further thoughts, open questions or idea on that incident.

Your observation report should be 1-2 pages (New Times Roman, single-spaced, 12 fonts) and due on November 13, 2013.

4. Auto-Geography (40 % of final mark)

According to McGregor (2004, p. 1), “We teach who we are.” The purpose of this assignment is for teacher candidates to locate themselves in an intersectional landscape: to reflect on your identity in relation to your family, your particular experience of intersectionality, the intersections that constitute your local community, and how these connect you to global communities. There is a historical and developmental aspect to this auto- geography: in order to understand your present location, you’ll need to get grounded in your past experience, and this will enable you to articulate your expectations for your future experiences as an educator as well. As educators, we continually reflect on and make meaning of our own privileges, biases and standpoints as a method for learning from our students about their diverse experiences, identities, circumstances, and backgrounds. While this assignment is designed as an auto-geographic experience for teacher candidates, like all of the assignments and experiences in this course, it can also be transformed in age-appropriate ways for use

3 with future students to enable them to locate themselves and reflect on their own complex identities and diverse experiences in society.

This assignment has three parts: (a) finding and/or creating artifacts, (b) a dialogue, and (c) a short reflection. You will be given some in-class time to develop first thoughts and ideas for this project. However, be prepared to work outside of class to complete your project. a. Finding and/or creating artifacts Find artifacts or create something that represent the questions: Where am I coming from?, Where am I now? and Where am I going? These found and/or created artifacts can represent one of the following aspects: 1) your identity, 2) your family, 3) the processes that most shape your intersectionality in local communities, and 4) the ways in which you are connected to global communities. Be selective about what you choose to include and/or create and focus on what is meaningful for you, rather than feeling like you have to “cover” everything. This auto-geography may include diverse forms of representation, such as an essay or a poem, a painting, a sculpture, a musical composition, a short movie or photographic sequence, or collage of meaningful objects. Leading questions could be: What experiences have been central to your evolving identity as an educator over time? What diverse family or cultural processes shape who you are and who you want to become? How do you imagine yourself in the future as an educator? You may find or create something to represent your past, present, and future or something that combines some or all of them. When addressing the content of these questions, some of the readings and topics of this course may be useful as an orientation (i.e., biases, communicating across differences, gender, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, poverty and social class, mental health, risk and resiliency). This assignment purposely gives you a lot of freedom so that you decide and choose what is most meaningful for you. b. Dialogue In our meeting on December 4th, we’ll hold small group dialogue circles to describe your auto-geography and learn from the feedback and experiences of one another. You will be given the opportunity to get feedback from your group on your auto-geography as well as to juxtapose your location to experiences and insights with those of some of your colleagues. You are asked to listen attentively as well as to create a supportive and thoughtful atmosphere in your group so that each of you is able to tell your stories and/or show your creations. It is your task and opportunity to communicate across differences, recognize diverse perspectives, and learn from these disparate experiences, as well as to acknowledge commonalities within your group. Please be prepared to explain why the artefacts you created or found are meaningful and relevant as well as to think about other’s auto-geographies and give them advice. Importantly, consider seriously how your own individual experiences shape your goals and expectations as a teacher and in turn your educational practice. We will also organize a ‘gallery walk’ at the last day of class so that we all can see the auto-geographies of each other. You may want to talk about ‘how’ you would like to present your project and/or what you would like to share with others.

c. Reflection Paper Due on the last day of class, December 11th, is a reflections paper on how the experiences of your project — creating it, talking to your colleagues and presenting it at the last day of class—will affect your teaching: 1) describe your project shortly and the process of making it, 2) describe the experiences presenting it and talking with your colleagues about it, 3) write about the reflection throughout the process and how those will influence you as a future teacher. How might it influence your practice in the classroom, communicating with families and the students, creating an open and warm classroom atmosphere, or anything alike. The paper should be between 1-2 pages (Times New Roman, single-spaced, font 12).

Reference: McGregor, S. (2004). Transformative Teaching. We Teach who We Are, in: Kan – Forum, Vol. 14, no. 2

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENTS

All written assignments should be submitted in written form (INSTRUCTOR TO SPECIFY PAPER OR ELECTRONIC0, double spaced, in 12 font, with page numbers and an appropriate bibliography, as necessary, presented in APA style (American Psychological Association). 4 LATE SUBMISSIONS You are expected to submit all course work by the specified due date unless arranged with the instructor at least one week in advance. Barring emergencies, any late assignments that have not been previously discussed with your instructor may result in a failure on that assignment.

PASS-FAIL MARKING As is the case for most courses in the Teacher Education Program, this course is graded using a pass/fail grading system. That is, only “pass” or “fail” will appear on your transcript, with “Pass” being equivalent to at least B+ performance (76% in UBC’s standard marking system). In a professional faculty, passing a c ourse entails both good academic performance as well as active participation in learning activities. St udents are expected to meet all criteria to receive a passing mark. Moreover, each assignment must earn a passing mark in order for the student to receive a passing final grade for the course. If an assi gnment does not meet expected standards, students will have one opportunity to revise and resubmi t the assignment. In such cases, the student must attach the first version of the assignment and highl ight the changes made in response to instructor feedback.

If a student has continued difficulty meeting expectations, he/she should discuss the situation with the instructor and also with the Teacher Education Office. It is the instructor’s responsibility to provide timely, speci fic and helpful feedback on student assignments.

ACADEMIC INTEGRITY AND PLAGIARISM The integrity of academic work depends on the honesty of all those who work in this environment and the observance of accepted conventions concerning such practices as acknowledging the work of others. Students are expected to complete their own work and to submit work that has been prepared for this class only. Plagiarism, submitting or presenting the work of another person as if it were one’s own, or submitting work prepared for another class can result in an automatic failure of this course. Moreover, students are also expected to acknowledge, as appropriate, the contributions of others in your submissions by way of appropriate referencing.

Plagiarism and other forms of academic misconduct are taken very seriously at UBC, whether committed by faculty, staff or students. Students should be aware of the sections of the University Calendar that address academic misconduct (www.students.ubc.ca/calendar) and of the university’s website on scholarly integrity (http://clc.library.ubc.ca/airc.html). The UBC library webpage on plagiarism and how to avoid it is also a very useful resource (www.library.ubc.ca/home/plagiarism/), with specific information on the many different forms that plagiarism can take, including accidental and intentional plagiarism (see: www.library.ubc.ca/home/plagiarism/for-students.doc or www.indiana.edu/~wts/pamphlets/plagiarism.shtml

If you have questions or concerns about any of these policies or conventions in relation to how they apply to the work you do in this course, please discuss them with the instructor.

5 IMPORTANT POLICIES

Please be aware of the following UBC, ECPS, and Teacher Education Policies:

Gender Inclusive Language Please incorporate and gender inclusive language in your oral and written language. This language positions women and men equally, it does not exclude one gender or the other, nor does it demean the status of one gender or another. It does not stereotype genders [assuming all childcare workers are female and all police officers are male], nor does it use false generics [using mankind instead of human kind, or using man-made instead of hand crafted]. In addition, this language requires gender balance in personal pronouns, for example, use "he and she" rather than "he" or balance gendered examples in a paper, referring to both male and female examples. You may also cast subjects in the plural form, for example, when a “student raises his hand” change to when “students raise their hands.”

Person First Language Please incorporate and use person first language in your oral and written language. Disabilities and differences are not persons and they do not define persons, so do not replace person-nouns with disability-nouns. Avoid using: the aphasic, the schizophrenic, the hearing impaired. Also avoid using: the hearing impaired client, the dyslexic lawyer, the developmentally disabled adult. Instead, emphasize the person, not the disability, by putting the person-noun first: the lawyer with dyslexia, the child with hearing impairment, the teacher with a physical impairment.

Professional Conduct Teacher candidates in the Faculty of Education are expected to adhere to principles of professional conduct while on campus and in schools. They are also expected to adhere to the policy of the university regarding respectful learning environment. Participants in this course are expected to demonstrate all of the qualities of professionalism, arriving at each class fully prepared, engaging actively in the teaching and learning process and interacting ethically with your peers and your instructor. Classes will be conducted within an atmosphere of respect, both for each other and for the ideas expressed by participants in class discussions and debates. My responsibility in this class is to model professional conduct and to guide you to an understanding of professionalism when you are on campus, and when you are on practicum in schools.

Students with Disabilities If you have a letter from the office of Access and Diversity indicating that you have a disability that requires specific accommodation, please present the letter to me so that we can discuss possible accommodation. To request academic accommodation due to a disability, first meet with an advisor in the Office of Access and Diversity to determine your eligible accommodations/ services. Please keep me and the Teacher Education office informed about requests for accommodation.

COURSE SCHEDULE

Week 1: Developmental Theories and Education: An Introduction September 4, 2013

Topic Teachers’ Beliefs and Understanding of Child Development Guiding What do teachers need to know about child development, and why is it important? What Questions are some of the prominent theories of development that inform education? How do ecological models of development and socialization inform educational practice? Required Class Text: Chapter 1 Introduction: Dimensions of Development (pp. 2-24) Readings Chapter 2 Theory and Research in Child Development (pp. 28-74)

Daniels, D.H., & Clarkson, PK. (2010). A developmental approach to educating young Recommended or children. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin/Sage. Chapter 1: Developmental perspectives and 6 Additional educational practice (pp. 7-30). Reading

Weeks 2-3: Teaching, Learning, and Cognitive Development September 11 & 25, 2013

Topic 1 Constructivist and Sociocultural Perspectives (September 11) Guiding QuestionsWhat are some of the key theories for teaching and learning? Teaching something doesn’t mean that children learn it. How do we link teaching and learning? How do we develop and ensure that understanding has taken place? What are the components that help children monitor their own understanding? Required Class Text: Chapter 6 - Cognitive Development in Early Childhood (assigned sections) Readings Chapter 9 - Cognitive Development in Middle Childhood Article: Killoran, I. (2003). Why is your homework not done? How theories of development affect your approach in the classroom. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 30, 309-315

Recommended or Furth, H. (1970). Piaget for teachers. Washington: Prentice Hall. Additional (all chapters are a great read for teacher candidates; book is available in the Education Library) Readings Siegler, R.S., & Alibali, M.W. (2005). Sociocultural theories of development (pp. 107-140). In Children’s Thinking. NJ: Prentice Hall.

Wadsworth, B. J. (1989). Piaget's theory of cognitive and affective development (4th edition). NY: Longman. Chapters 1 & 2 (pp. 1-32) Topic 2 Neuroscience and Cognitive Development (September 25) Guiding Questions What does the latest research in neuroscience tell us about student learning? What are some ways in which teachers can be informed by this research to promote student learning? Required Video PBS: “The Human: Brain Matters” (50 minutes placed in four 15-minute clips found on Youtube) Clip 1 of 4: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5rkuC7ijHKQ&feature=relmfu Clip 2 of 4: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gFhP6q9IR7s&feature=relmfu Clip 3 of 4: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wrL25yhHo_8&feature=relmfu Clip 4 of 4: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TKMuXjS0Z8w&feature=relmfu

Required Reading Articles: Immordino-Yang, M. H., & Damasio, A. (2007). We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education. Mind, Brain and Education, 1, 3-10.

Read one of the following (as assigned, to facilitate class discussion):

a) “6 Tips for Brain-Based Learning” (2011) (edutopia.org)

b) Fisher, R. (1998). Thinking about thinking: Developing metacognition in children. Early Child Development and Care, 141 (1), 1-15. doi:10.1080/0300443981410101 Topic 3 Intellectual and Academic Achievement; Reading, Writing and Numeracy (September 25) Guiding How do we conceptualize intelligence among school children? What theories of intelligence Questions inform educational practice? What happens when students do not demonstrate the intellectual competencies needed for school success? How do academic skills develop in the basic content areas (e.g., reading, writing, numeracy)? Required Class Text: Chapter 8: intelligence Readings Chapter 10: Development in the Academic Domains (assigned sections)

Week 4: Engaging Students: Motivation, Self Perceptions and Self-Regulation October 2, 2013

7 Guiding How do children develop a concept of self? How does a students’ beliefs about self impact Questions their classroom behaviour and success? How can teachers support student’s development of self-regulation? What are the critical issues in motivation, and what does the latest research tell us about how to motivate students? What are the ways in which teachers can facilitate or impede student motivation? Required Class Text: Chapter 13 – Development of Motivation and Self-Regulation Reading Articles: Ames, C. A. (1990). Motivation: What teachers need to know. Teachers College Record, 91, 409- 421.

Read ONE of the following (submit QRQ reflection):

a) Dweck, C. (2007). Boosting student achievement with messages that motivate. Education Canada,47, 6-10.

b) Kohn, A. (2001). Five reasons to stop saying “good job.” Young Children, 56, 24-28.

Week 5-6: Social, Emotional and Moral Development and Learning October 9 & 16, 2013

Topic 1 Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) (October 9) Guiding What is SEL? How does SEL support successful student outcomes? How can SEL be taught in Questions classrooms and schools? How does SEL relate to various instructional strategies and other school initiatives? Required Class Text: Chapter 7 - Social Emotional Development in Early Childhood Reading Chapter 10 - Social Emotional Development in Middle Childhood

Schonert-Reichl, K. A., & Hymel, S. (1996). Promoting social development and acceptance in Recommended the elementary school classroom. In J. Andrews (Ed.), The inclusive or Additional classroom: Challenging issues and contemporary practices (pp. 152-200). Scarborough, readings Ontario: Nelson Canada.

Jennings, P.A. & Greenberg, M.T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79 (1), 491-525. (Available on-line through UBC library). Topic 2 Morality and Behaviour: Fostering prosocial vs aggressive behaviour (October 16) Guiding How do children develop a sense of right and wrong during the school years? What are the Questions factors – both individual and contextual – that influence development? How can teachers foster positive moral development? How does this impact student behavior? Required Video CBC-TV: The Nature of Things: “Babies: Born to be Good?” (45 mins.) http://www.cbc.ca/natureofthings/episode/born-to-be-good-1.html

Required Hymel, S., Schonert-Reichl, K.A., Bonanno, R. A., Vaillancourt, T., & Rocke Henderson, N. Reading (2010). Bullying and Morality: Understanding How Good Kids Can Behave Badly. In Jimerson, S., Swearer, S.M. & Espelage, D.L. (Eds). The Handbook of Bullying in Schools: An International Perspective (p. 101-118). New York: Routledge

Recommended Nucci, L. (2009) Nice is not enough: Facilitating moral development. Columbus OH: Pearson. or Additional (available in PRTC Library in the SEL Collection) Readings

Week 7: Recognizing the Intersections of “Difference” and Communicating Across Differences October 23, 2013

Topic Intersectionality and Difference, Issues and Strategies for Communication in Diverse School and Classroom Settings Guiding How do different kinds of “differences” intersect in different contexts? How might educators 8 Questions make sense of students as classed, “raced,” gendered, abled, subjects? What are some of the communication issues that arise with respect to diverse learners? What are some strategies for enacting essential communication skills for promoting, maintaining and managing classroom behaviour, conducting parent teacher meetings, and creating professional interactions with peers and administrators in diverse classrooms and school settings? Required Book of Readings: Bingham, C. (2001). Encounters in the Public Sphere, In Bingham, C. Reading (Ed.) Schools of Recognition: Identity Politics and Classroom Practices (pp. 29-55), Chicago, IL: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers [Research Article with Experiences from Teachers] Recommended or Additional Book of Readings: Archibald, J. (2008). The Power of Stories to Educate the Heart, in: J. Reading Archibald, Indigenous Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, Body, and Spirit (pp. 83-101). UBC Assignment Press. Due: Lesson Plan

Week 8: Gender, Sexuality and Sexual Identity November 13, 2013

Topic 1 Gender and Development, Gender in the Classroom, Gender as Subculture Guiding What role does gender play in the classroom? How does gender influence classroom Questions interactions? What are the implications for gender subcultures in teaching?

Required Book of Readings: Chapman, A. (2012). Gender Bias in Education. Critical Multicultural Reading Pavilion/Research Room, ed. by P. C. Gorski. [Research Article]

Recommended Book of Readings: Moffatt, L. and Norton B. (2008). Reading Gender Relations and or Additional Sexuality: Preteens Speak Readings out. Canadian Journal of Education, 31/1 (2008), p. 102-123 [Narration, Teacher’s Experience or Critical Comment]

Web link: Gender differences in Education : http://www.education.com/topic/gender- differences/

R. P. Coulter on ‘What about the Girls’, in: Canada Education, Vol. 53, 1, 2013: Assignment http://www.cea-ace.ca/education-canada/article/what-about-girls Due: Observation Report Topic 2 Gender and Sexual Identity in Classroom and School Settings Guiding Gender identity, sexual identity, and changing notions of family in Canadian society: What Questions are the implications for teaching and learning? What are some of the issues that arise for adolescents who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered, or questioning in school settings? How do we create inclusive educational environments for students in school and classroom settings? Required Book of Readings: Talburt, S. (2004). Constructions of LGBT Youth: Opening Up Subject Reading Positions. Theory into Practice, Vol. 43/2, Spring 2004, p. 116-221 [Research Article] Auto- First Ideas for your Auto-Geography: Geography

Week 9: Race, Culture and Ethnicity November 20, 2013

Topic Issues Around Race/Ethnicity and Culture in the Classroom and School Setting. 9 Guiding What are the ways that race and ethnicity play a role in teaching and learning? Questions Required Book of Readings: May, S. and Sleeter, Ch. (2010). Critical Multiculturalism. Theory and Reading Practice. Routledge p. 1-16 (Introduction) [Research Article]

Recommended Book of Readings: Michaels, S., O’Connor, C. and Resnick, L. (2008). Deliberative Discourse or Additional Idealized and Readings Realized: Accountable Talk in the Classroom and in Civic Life, in: Stud Philos Educ 27, p. 283–297 [Narration, Teacher’s Experience or Critical Comment]

Oran, G. (2009). Culturally Relevant Pedagogy. In: Education.com Link: http://www.education.com/reference/article/culturally-relevant-pedagogy/

Week 10: Social Class and Poverty November 27, 2013

Topic Understanding Social Class and Poverty in Classroom and School Settings Guiding How do social class and poverty influence learning and teaching? What does the current Questions research in Canada report about poverty and social class in children and their families? What is the effect of socioeconomic disadvantage on child development outcomes? Required Book of Readings: Killen, M., Rutland, A., Ruck M. D. (2011). Social Policy Report: Reading Promoting Equity, Tolerance, and Justice in Childhood, Volume 25, number 4

Read ONE of the following (as assigned, to facilitate class discussion):

a) Freire, P. (1993). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum Books, Chapter 1 [Research Article]

b) Book of Readings: Huston, A. C. and Bentley, A. C. (2010). Human Development in Societal Context, Annual Review of Psycholology, 61:411-437. Available through the UBC library Recommended webpage [Narration, or Additional Teacher’s Experience or Critical Comment] Readings BC Child and Youth Advocacy Coalition: http://www.firstcallbc.org/pdfs/economicequality/3-reportcard2011.pdf

Week 11: Mental Health December 4, 2013

Topic Mental Health Promotion in Schools Guiding What is mental health and mental illness in children and youth? How do you understand the Questions most common mental health concerns of children/youth? How can you identify associated behavioral symptoms? What are the appropriate ways to make appropriate recommendation for referral to psychological services in your school District/community? Required Class Text: Chapter 4- Table 4.1 Common Chromosomal and Genetic Disorders in children Readings Chapter 5 - Pages 172-175 – Overweight Youth and Eating Disorders Pages 181-185 – Health–Compromising Behaviours Book of Readings: Making a Difference: An Educator’s Guide to Child and Youth Mental Health Problems. [Research Article]

Recommended Book of Readings: Adelman, H., & Taylor, L. (2006). Mental health in schools and public or Additional health. Public Health Readings Reports, 121, 294-298. [Narration, Teacher’s Experience or Critical Comment]

10 SFU publication on mental health issues in children: http://www.childhealthpolicy.sfu.ca/research_quarterly_08/index.html

The ABCs of Mental Health: A Teacher Resource (Ontario): http://www.brocku.ca/teacherresource/ABC/index.php Auto- Presentation and Dialogues about Auto-Geographies: Geography Time for Dialogues about the Auto-Geographies in small groups

Week 12: Risk and Resiliency December 11, 2013

Topic Issues of risk and resiliency in classroom and school settings: Promoting positive development in all students. Guiding What is risk? What is resiliency? What are the ways in which to promote students’ positive Questions development in classrooms and schools? Required Book of Readings: Schonert-Reichl, K.A. & LeRose, M. (2008), Considering Resilience in Readings Children and Youth: Fostering Positive Adaptation and Competence in Schools, Families, and Communities. Discussion Paper for The Learning Partnership. The National Dialogue on Resiliency in Recommended Youth or Additional Readings Lincoln High School in Walla Walla, WA, tries new approach to school discipline: Available online at: http://acestoohigh.com/2012/04/23/lincoln-high-school-in-walla-walla- wa-tries-new-approach-to-school-discipline-expulsions-drop-85/ [Narration, Teacher’s Experience or Critical Comment]

Learning Partnership Webpage on Resiliency: http://www.thelearningpartnership.ca/page.aspx?pid=819, http://www.canadianschoolhealth.ca/page/Joint+Statement+on+School+Mental+ Health+Promotion, http://resiliencetrumpsaces.org/providersin.cfm (with an online course). Auto- Gallery Walk and submission of reflection papers Geography

WEB RESOURCES

Collaborative for Academic and Social and Emotional Learning or CASEL (www.casel.org) Find Youth Info – Resources/programs to help youth-serving organizations & community partners (www.findyouthinfo.gov) Edutopia- What works in public education, George Lucas Foundation (www.edutopia.org) Centre for Social and Emotional Education (www.csee.net) Developmental Studies Center - Caring School Communities Project (www.devstu.org) Teach Safe Schools (www.teachsafeschools.org) Educators for Social Responsibility (ESR) (www.esrnational.org/home.htm) Education.com - Online Magazine with special issue on bullying by researchers around the globe (www.education.com) The UBC Human Early Learning Partnership (www.earlylearning.ubc.ca/) Public Health Agency of Canada’s (PHAC) Best Practices Portal (www.cbpp-pcpe.phac-aspc.gc.ca/) The Roots of Empathy (www.rootsofempathy.org) Committee for Children (www.cfchildren.org/) Developmental Studies Center (www.devstu.org/) Search Institute (focus on developmental assets) (www.search-institute.org/)

11 SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READINGS

Aboud, F. (1993). The developmental psychology of racial prejudice. Transcultural psychiatric research review, 30, 229-242.

Adelman, H. S., & Taylor, L. (2006). School and community collaboration to promote a safe learning environment. State Education Standard. Journal of the National Association of State Boards of Education, 7, 38–43.

Adelman, H., & Taylor, L. (2006). Mental health in schools and public health. Public Health Reports, 121, 294-298.

Anderson-Butcher, D., & Ashton, D. (2004). Innovative models of collaboration to serve children, youths, 12. families, and communities. Children & Schools, 26, 39–53.

Aviles, A, Anderson, T., & Davila, E. (2006). Child and adolescent social-emotional development within the context of school. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 11, 32-39.

Bank, J. A. (1999). An introduction to multicultural education. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Banks, J. A. (1997). Teaching Strategies for Ethnic Studies (6th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Bear, G. G., Manning, M. A., & Izard, C. E. (2003). Responsible behaviour: The importance of social cognition and emotion. School Psychology Quarterly, 18, 140-157.

Berkowitz, M. W., & Bier, M. C. (2005). What works in character education: A research driven guide for educators. Character Education Partnership.

Brackett, M.A., Katulak, N., Kremenitzer, J. P., & Caruso, D. (in press). Emotionally literate teaching. In M.A. Brackett, J. P. Kremenitzer with M. Maurer, M. Carpenter, S. E. Rivers, & N. Katulak (Eds.), Emotional literacy in the classroom: Upper elementary. Rochester, NY: National Professional Resources.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 793- 828). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Canadian Council on Learning (2006). The Social Consequences of Economic Inequality for Canadian Children: A Review of the Canadian Literature. Retrieved March 13, 2010 from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/research/social_consequences2.pdf

Canadian Institute for Health Information (2009). Improving the Health of Canadians: Exploring Positive Mental Health (Ottawa: CIHI).

Davidman, L., & Davidman, P. T. (2001). Teaching with a multicultural perspective: A practical guide (3rd ed.). New York: Addison-Wesley.

Defrates-Densch, N. (2007). Case studies in child and adolescent development for teachers. McGraw- Hill.

Delpit, L. (1995). Other people’s children: Cultural conflict in the classroom. New York: The New Press.

12 Duckitt, J. (1992). Psychology and prejudice: A historical analysis and integrative framework. American Psychologist, 47, 1182-1193.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K.B. (in press). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development.

Eccles, J. (1999). The development of children ages 6 to 14. The Future of Children, 9, 30-44.

Elias, M. (2009). Four key to helping at-risk kids. Retrieved March 13, 2010 from http://www.edutopia.org/strategies-help-at-risk-students.

Elias, M.J., & Arnold, H. (2006). The educator’s guide to emotional intelligence and academic achievement: Social-emotional learning in the classroom. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Faltis, C. (2001). Teaching and learning in multilingual classrooms. (3rd ed.). Columbus, OH: Merrill Prentice Hall.

First Call BC (2009). Child Poverty Report Card. Retrieved March 13, 2010 from www.firstcallbc.org

First Call BC (2007). Child and Youth Development and Income Inequality: A review of selected Literature. Retrieved March 13, 2010 from http://www.firstcallbc.org/pdfs/EconomicEquality/3-lit %20review.pdf.

Gardner, H. (2009). The five minds for the future: Cultivating and integrating new ways of thinking to empower the education enterprise. The School Administrator Magazine, February, 16–20.

Gorski, P. (2008, April). The myth of the culture of poverty. Educational Leadership, 65, 32-36.

Greenberg, M. T. (in press). School-based prevention: Current status and future challenges. Affective Education.

Greenberg, M. T., Domitovich. C., and Bumbarger, B. (2001). The prevention of mental disorders in school-aged children: Current state of the field. Prevention & Treatment, 4, Article 1.

Hargreaves, A. (1998). The emotional practice of teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 14, 835– 854.

Hargreaves, A. (2000). Mixed emotions: Teachers’ perceptions of their interactions with students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16, 811–826.

Inman, S. (2010). After her brain broke: Helping my daughter recover her sanity. Dundas, ON: Bridgeross Communications.

Jensen, E. (2009). Teaching with Poverty in Mind: What Being Poor Does to Kids' Brains and What Schools Can Do About It.

Luthar, S. S. (2006). Resilience in development: A synthesis of research across five decades. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental Psychopathology: Risk, disorder, and adaptation (pp. 740-795). New York: Wiley.

Luthar, S.S. (2003). The culture of affluence: Psychological costs of material wealth. Child Development, 74, 1581-1593.

13 McLloyd, V. (1998). Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist, 53, 185-204.

McLoyd, V., Ceballo, R., & Mangelsdorf, S. (1996). The effects of poverty on children's socioemotional development. In J.N oshpitz (Series Ed.) & N. Alessi (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child and adolescent psychiatry: Vol.4. Varieties of development (pp. 189–206). New York: Wiley.

Merrell, K. W., & Gueldner, B. A. (2010). Social and emotional learning in the classroom: Promoting mental health and academic success (Chapter 6: “When social and emotional learning in the classroom is not enough – Linking students to mental health services,” pp. 103-122). New York: The Guilford Press.

Nieto, S. (1999). The light in their eyes: Creating multicultural learning communities. New York: Teachers College Press.

O’Dougherty Wright, M. & Masten A. S. (2006). Resilience processes in development. In Goldstein, S., & Brooks, R.B. (Eds), Handbook of resilience in children. Cambridge University Press.

Pagani, L., Boulerice, B., & Tremblay, R. (1997). The influence of poverty on children's classroom placement and behavior problems. In G. Duncan & J. Brooks-Gunn (Eds.), Consequences of growing up poor (pp. 311–339). New York: Sage.

Pons, F., & Harris, P. L., & Doudin, P. A. (2002). Teaching emotion understanding. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 17, 293-304.

President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. (2003). Achieving the promise: Transforming mental health care in America. Final Report (DHHS Pub. No SMA-03-3832). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Reeve, J., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Self-determination theory: A dialectical framework for understanding socio-cultural influences on student motivation. In D. M. McInerney & S. Van Etten (Eds.), Big Theories Revisited (pp. 31-60). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Press.

Ryan, R. M., & Brown, K. W. (2005). Legislating competence: The motivational impact of high stakes testing as an educational reform. In A. E. Elliot & C. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence (pp. 354-374). NY: Guilford Press.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54-67.

Schonert-Reichl, K. A., & Hymel. S. (2007). Educating the heart as well as the mind: Why social and emotional learning is critical for students’ school and life success. Education Canada, 47, 20-25.

Solomon, D., & Watson, M. S., Battistich, V. A. (2001). Teaching and schooling effects on moral/prosocial development. In V. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Teaching, 4th Edition (pp. 566-603). Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

Singer, T., & Lamm, C. (2009). The social neuroscience of empathy. The Year in Cognitive Neuroscience, New York Academy of Sciences, 1156, 81-96.

Smith, B. H., Molina, B. S., Massetti, G. M., Waschbusch, D. A., & Pelham, W. E. (2008). School-wide interventions—The foundation of a public health approach to school-based mental health. In S. Evans, M. Weist, & Z. Serpell (Eds.), Advances in school-based mental health interventions (pp. 7- 2:19). Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute. 14 Stepien, W., & Gallagher, S. (2003). Problem-based learning: As authentic as it gets. Educational Leadership, April, 25-28.

Tiedt, P. L., & Tiedt, I. M. (1999). Multicultural teaching (5th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Torp, L., & Sage, S. (1998). Problems as possibilities: Problem-Based Learning for K-12 Education. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

von Stumm, S., Hell, B., & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2011). The hungry mind: Intellectual curiosity is the third pillar of academic performance. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 574-588. doi:10.1177/1745691611421204

Warneken, F., Hare, B., Melis, A. P., Hanus, D., & Tomasello, M. (2007). Spontaneous altruism by chimpanzees and young children. PLoS Biology, 5, 1414–1420.

Warneken, F., & Tomasello, M. (2006). Altruistic helping in human infants and young chimpanzees. Science, 311, 1301–1303.

Warneken, F., & Tomasello, M. (2008). Extrinsic rewards undermine altruistic tendencies in 20-month- olds. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1785–1788.

Warneken, F. & Tomasello, M. (2009). The roots of human altruism. British Journal of Psychology. Target article with commentaries, 100, 445-471.

Warneken, F. (2009). Digging deeper: A response to commentaries on ‘The roots of human altruism’. British Journal of Psychology, 100, 487-490.

World Health Organization. (1986). Ottawa charter of health promotion. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available for download at http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/index.html

Zins, J. E., Weissberg, R. P., Wang, M. C., & Walberg, H. J. (Eds.). (2004). Building academic success on social and emotional learning: What does the research say? New York: Teachers College Press.

15