TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

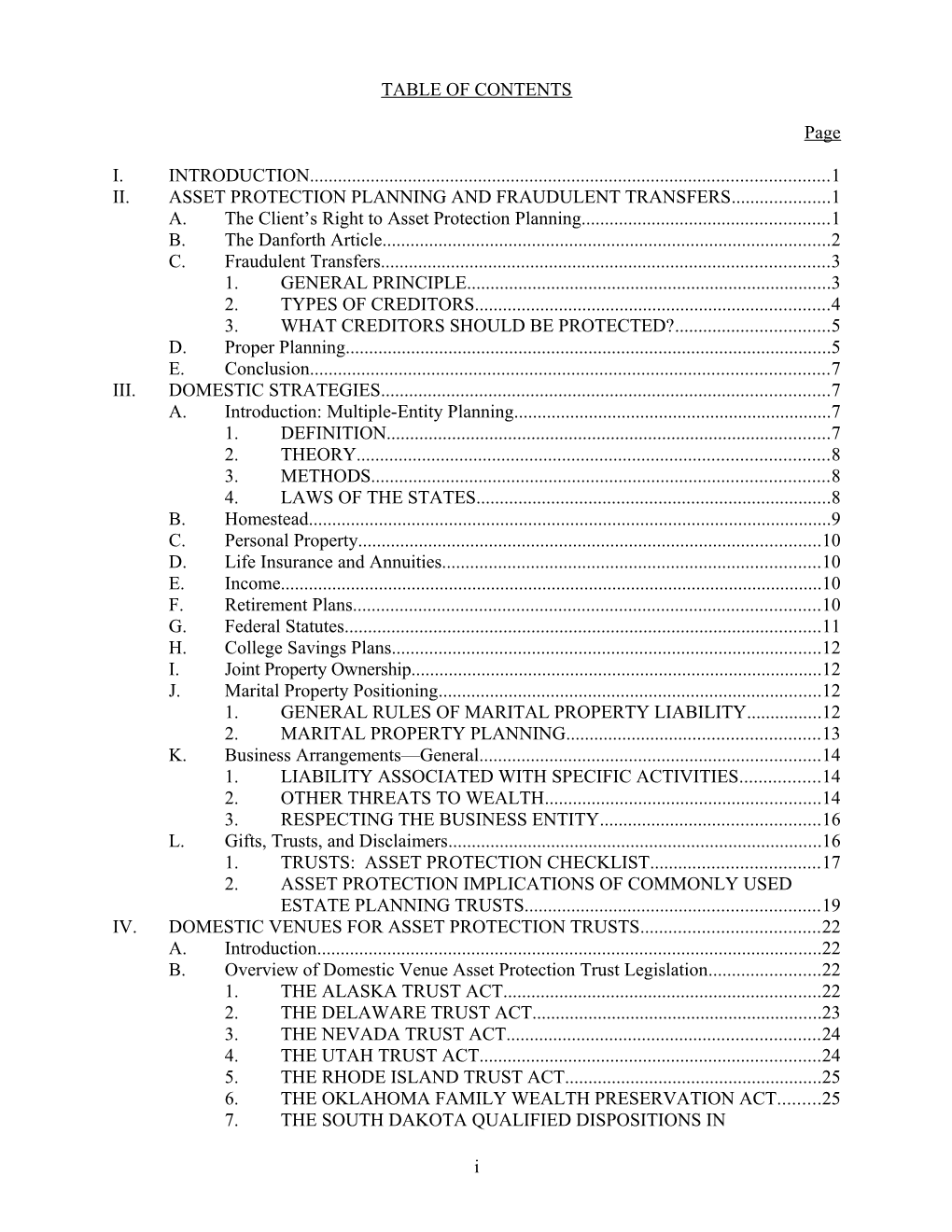

I. INTRODUCTION...... 1 II. ASSET PROTECTION PLANNING AND FRAUDULENT TRANSFERS...... 1 A. The Client’s Right to Asset Protection Planning...... 1 B. The Danforth Article...... 2 C. Fraudulent Transfers...... 3 1. GENERAL PRINCIPLE...... 3 2. TYPES OF CREDITORS...... 4 3. WHAT CREDITORS SHOULD BE PROTECTED?...... 5 D. Proper Planning...... 5 E. Conclusion...... 7 III. DOMESTIC STRATEGIES...... 7 A. Introduction: Multiple-Entity Planning...... 7 1. DEFINITION...... 7 2. THEORY...... 8 3. METHODS...... 8 4. LAWS OF THE STATES...... 8 B. Homestead...... 9 C. Personal Property...... 10 D. Life Insurance and Annuities...... 10 E. Income...... 10 F. Retirement Plans...... 10 G. Federal Statutes...... 11 H. College Savings Plans...... 12 I. Joint Property Ownership...... 12 J. Marital Property Positioning...... 12 1. GENERAL RULES OF MARITAL PROPERTY LIABILITY...... 12 2. MARITAL PROPERTY PLANNING...... 13 K. Business Arrangements—General...... 14 1. LIABILITY ASSOCIATED WITH SPECIFIC ACTIVITIES...... 14 2. OTHER THREATS TO WEALTH...... 14 3. RESPECTING THE BUSINESS ENTITY...... 16 L. Gifts, Trusts, and Disclaimers...... 16 1. TRUSTS: ASSET PROTECTION CHECKLIST...... 17 2. ASSET PROTECTION IMPLICATIONS OF COMMONLY USED ESTATE PLANNING TRUSTS...... 19 IV. DOMESTIC VENUES FOR ASSET PROTECTION TRUSTS...... 22 A. Introduction...... 22 B. Overview of Domestic Venue Asset Protection Trust Legislation...... 22 1. THE ALASKA TRUST ACT...... 22 2. THE DELAWARE TRUST ACT...... 23 3. THE NEVADA TRUST ACT...... 24 4. THE UTAH TRUST ACT...... 24 5. THE RHODE ISLAND TRUST ACT...... 25 6. THE OKLAHOMA FAMILY WEALTH PRESERVATION ACT...... 25 7. THE SOUTH DAKOTA QUALIFIED DISPOSITIONS IN

i Table of Contents (continued) Page

TRUST ACT...... 26 8. THE MISSOURI UNIFORM TRUST CODE...... 26 C. Domestic Venue Asset Protection Legislation Vulnerabilities...... 27 1. FULL FAITH AND CREDIT PROBLEMS...... 27 2. SUPREMACY CLAUSE CONCERNS...... 31 3. CONTRACT CLAUSE PROBLEMS...... 36 D. Aside from Constitutional Problems, the Status of Domestic Venues as Pro-Debtor Jurisdictions is Questionable...... 37 V. OFFSHORE TRUSTS...... 37 A. General Principles...... 37 B. Methods of Attack...... 37 C. Exporting the Assets Versus Importing the Law...... 38 1. EXPORT THE ASSETS...... 38 2. IMPORT THE LAW...... 38 D. Enforcement of Judgments...... 39 E. Transfer of Situs...... 39 F. Location of Trust Assets...... 40 G. Nest Egg vs. In Toto...... 40 1. IN TOTO...... 40 2. NEST EGG...... 40 H. Control...... 40 I. Beneficial Enjoyment...... 41 VI. PRACTICAL IMPLEMENTATION...... 41 A. Step One: Investigate the Client and the Situation...... 41 1. FINANCIAL CONDITION...... 41 2. CLAIMS OR THREATENED CLAIMS...... 41 3. THE SOLVENCY ANALYSIS...... 41 4. POSSIBLE CRIMINAL ACTIVITY...... 42 5. COMPETENT ASSISTANCE...... 43 B. Step Two: Explore Motives...... 43 1. ECONOMIC OR INVESTMENT ISSUES...... 43 2. TAX OR ESTATE PLANNING ISSUES...... 43 3. PERSONAL OR FAMILY ISSUES...... 44 C. Step Three: Select Jurisdiction...... 44 1. AGGRESSIVE VS. NON-AGGRESSIVE LEGISLATION...... 45 2. RELUCTANCE TO RELOCATE ASSETS...... 45 3. CONSIDER THE LIKELY ORIGIN OF A CLAIM...... 45 4. LOCAL LAW...... 45 5. ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL STABILITY...... 46 6. COSTS...... 46 7. TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATIONS...... 46 8. BANKS AND INVESTMENT ADVISORS...... 47 9. CRIMINAL ACTIVITIES...... 47 10. INFLUENCES OF OTHER COUNTRIES...... 47

ii Table of Contents (continued) Page

D. Step Four: Plan the Structure of the Offshore Arrangement...... 47 1. STRUCTURAL VARIATIONS...... 47 2. DRAFT AGREEMENT...... 49 3. LOSS OF CONTROL...... 49 4. ADDRESSING THE CONTROL ISSUE...... 49 5. RELATED PLANNING FOR PROTECTING ASSETS...... 50 6. DOCUMENTS...... 51 E. Step Five: Select Local Professionals...... 52 1. MORE THAN ONE PROFESSIONAL REQUIRED...... 52 2. FAMILIARITY WITH PROFESSIONALS...... 52 F. Step Six: Review Recent Case Law...... 52 G. Step Seven: Obtain Legal Advice...... 55 H. Step Eight: Execute the Documents and Deliver the Funds...... 56 VII. CONCLUSION...... 56

CHART A EXPORT THE ASSETS...... 57 CHART B IMPORT THE LAW...... 58 CHART C PRIVATE TRUST COMPANY/PURPOSE TRUST...... 59 CHART D "DROP-DOWN" CORPORATION...... 60 CHART E "SISTER" CORPORATION...... 61 CHART F LIMITED PARTNERSHIP...... 62 CHART G EXISTING CORPORATION (CONTROLLED BY SETTLOR)...... 63

iii PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 1

PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION1

I. INTRODUCTION

There is increasing demand from wealthy clients for asset protection planning advice. Many such individuals sense a risk of serious economic threats and liabilities no matter what professional, business, or personal activities they undertake. They genuinely believe that the plaintiff's bar can make a case and generate liability under even the most absurd and unlikely sets of facts, and they consider our legal system to be capricious, unpredictable, and unlikely to render a fair result. Running parallel with this cynicism toward the court system is a similar skepticism with respect to legislative and regulatory bodies. Because of laws like CERCLA2, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 20023, and the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005 (the “BAPCPA”), business men and women have become increasingly wary of the government’s propensity to pass new legislation with potential liability consequences of dire and immediate impact.

At least six recent articles4 have raised the issue that a lawyer engaged in estate planning may have a duty to his clients to advise them about asset protection planning in addition to more traditional trust, estate, and tax planning advice. Whether or not such a duty exists, prudence suggests that estate planning attorneys be fully informed and able to address asset protection issues with their clients.

II. ASSET PROTECTION PLANNING AND FRAUDULENT TRANSFERS

A. The Client’s Right to Asset Protection Planning

The debate between advocates of creditors rights and advocates of asset protection is now, and long has been, a vigorous one. Articles on both sides of the debate from practicing lawyers are numerous and informative. Until recently, however,5 most of the articles written by law professors on this topic were “Johnny-one-note” choruses of criticism of asset protection planning (almost polemical in some cases) punctuated with titles ringing of indictment, such as: “Putting a Stop to ‘Asset Protection’ Trusts,”6 “Domestic Asset Protection Trusts: Pallbearers to Liability?,”7 “Asset Protection Trusts: Trust Law’s Race to the Bottom?,”8 and “Offshore Asset Protection Trusts: Testing the Limits of Judicial Tolerance in Estate Planning.”9

While proclamations from the ivory tower have occasional value for the practitioner, it is far too easy for a legal purist peering down from high aloft to focus on a few instances of flagrant abuse by asset protection planners and their clients, such as the Anderson10 and Lawrence11 cases, stake out a position of moral outrage, and then universally condemn anyone who dares to engage in asset protection planning. Although perhaps satisfying to the author’s sensibilities and finely-honed sense of moral rectitude after years in the academic community, such a reaction is simplistic, unhelpful, and unsupportable after even a cursory look at the law, the asset planning abuse protections already well established in the law (i.e., fraudulent transfer prohibitions and sanctions), and the equally well recognized legitimate nature PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 2 and function of estate and asset planning activities (e.g., wills, trusts, homesteads, life insurance, annuities, retirement plans, family limited partnerships, tenancies by the entirety, and on and on and on…).12

Almost all estate planning lawyers, almost all of the time, represent honorable, law abiding clients, men and women who daily contribute to society by their productivity and with their generosity, who pay their bills and their taxes, and who are not deadbeats, cheats, frauds or criminals. These same good people, some of whom have acquired significant wealth by their own hard work or that of their forebears, are legitimately concerned about the excesses of an American litigation system which sometimes more resembles a lottery-like payoff game than it does a reliable forum for the settlement of genuine claims. These clients of integrity, the persons who make up the vast majority of the clients with whom ethical attorneys deal every day, are both willing and eager to plan and act within the time-honored and well established rules of estate planning and asset protection planning. Such clients have the right to conduct estate and asset protection planning, and, as some have argued, we attorneys have a duty to assist them in this endeavor.13

Let’s be clear on this notion of duty. Even if some estate planning attorneys resist the idea, you can be assured the plaintiffs’ bar will not. The next wave of creative malpractice actions could well be against estate planning attorneys who fail to advise clients about asset protection alternatives, filed by clients who have suffered financial reverses which could have been avoided with such planning. The estate planner’s defense would be, of course, that “I do not do asset protection planning. I was engaged for estate planning purposes.” And any semi- competent plaintiff’s lawyer would have a field day with that response. Make no mistake about it, estate planning is about asset protection. Indeed, what are we estate planners about if not the preservation of wealth? Is the tax collector’s grasp the only one we are charged to avoid by all legitimate means for our clients? The creditor’s lawyer and the divorce lawyer can be every bit as much a predator as the tax collector. To ignore legitimate asset protection planning alternatives (including the asset protection trust) is to court disaster, for both your client and yourself.

The debate between advocates of creditor’s rights and advocates of asset protection cannot, then, turn on whether asset protection is proper. Rather, the only meaningful debate is the determination of the lawful and proper scope of asset protection planning.14

B. The Danforth Article15

In January 2002, Robert T. Danforth of Washington and Lee University School of Law published a balanced, provocative, and insightful article on creditor’s rights and trust law in the Hastings Law Journal. Anyone ready to take sides in the debate on creditor’s rights versus asset protection planning should read this thoughtful presentation for the new perspectives it brings to that debate. While there is far too much substance in Professor Danforth’s article to attempt to summarize his arguments and observations here, a few of his comments and conclusions are particularly noteworthy. PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 3

Professor Danforth’s most provocative and significant conclusion stems from his examination of the tautological maxim of American law that one cannot create a self-settled spendthrift trust. Professor Danforth points out that while the rule is essentially set forth in both Professor Austin Wakeman Scott’s treatise16 and the Restatement (Second) of Trusts17 (for which Professor Scott was the reporter and principal author), neither source offers a solid, independent rationale or theoretical basis for the rule.18 Moreover, and most interesting, the cases cited by Professor Scott do not, in fact, support the rule as he lays it out.19 As Professor Danforth gently remarks about these cases, it seems that “(Professor Scott) read them somewhat generously in support of his position.”20

Professor Danforth further argues that the rule against self-settled spendthrift trusts as espoused by Scott is not based on sound legal theory for a number of reasons. 21 First, the rule ignores the rights of non-settlor beneficiaries, since the creditor can defeat the interests of those beneficiaries as well as the interests of the settlor.22 It assumes a collusion between the settlor and the trustee in which the trustee will blindly comply with the settlor’s bidding, ignoring the legal obligations of fiduciaries.23 It grants creditors greater rights than the settlor, since the creditor can compel distributions and the settlor cannot.24 Finally, the rule fails to distinguish situations in which the settlor retains a power of disposition from those in which the settlor does not.25

Professor Danforth reminds us that such learned scholars of jurisprudence as Dean Erwin N. Griswold have criticized any rule against self-settled spendthrift trusts.26 Mindful that heirs and donees of wealth could avoid exposing inherited or gifted assets to the risks of creditors by having those assets placed in a spendthrift trust created by a parent or donor, Dean Griswold noted:

“[W]e may well question the soundness of a rule which allows a man to hold the bounty of others free from the claims of his creditors, but denies the same immunity to his interest in property which he has accumulated by his own effort.”27

C. Fraudulent Transfers

Asset protection planning is like tax planning, and all estate planning lawyers do tax planning. To do tax planning properly and legally, it must be done within the rules set forth in the tax code and tax regulations. In asset protection planning, the parallel rules are, in essence, the laws of fraudulent transfer.28

1. GENERAL PRINCIPLE.29 The statutory law regarding fraudulent transfers derives from the Statute of Elizabeth enacted in the year 1570. Most notably, this law declares "utterly void" conveyances, alienations, etc. designed to "delay, hinder, or defraud creditors."30 The Statute of Elizabeth is the historical model for modern fraudulent transfer statutes. At its heart, the Statute of Elizabeth is a legal remedy.

The general principle upon which the remedy (i.e., fraudulent transfer law) rests is that if a court determines that an asset transfer is fraudulent, a creditor can set aside the transfer. The fraud can be actual or constructive, and the law protects both existing and future PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 4 creditors.31 While statutes provide the general legal framework, case law usually supplies guidance in the determination of whether a transfer was made sufficiently in advance of the ripening of a creditor obligation so as not to be deemed fraudulent, but rather be considered prudent and permitted planning.

2. TYPES OF CREDITORS. At the risk of oversimplification, there are three categories of creditors one must consider when planning asset protection strategies.

a. Present Creditor. A present creditor is one against whom a tort was committed, or with whom a debt was contracted, by the client prior to the asset transfer in question.32 Credit card debt is an obvious example. Although intent to defraud always renders a transfer fraudulent, such intent need not be proved by a present creditor seeking to set aside a transfer. Rather, a transfer is fraudulent as to a present creditor if, regardless of the transferor's intent, the transfer renders the transferor insolvent.

b. Potential Subsequent Creditor. A potential subsequent creditor is a creditor whom a client could reasonably expect to face, i.e., a reasonably foreseeable claimant. In this category, the obligation arises after the asset transfer, and so the law is, by definition, protecting a future creditor. However, the event giving rise to the obligation may occur before the asset transfer. For example, in the tort context, one person may injure another, then transfer assets, and subsequently become a debtor of the injured party through a court judgment. In these circumstances, the transferor’s intent (whether actual or constructive) becomes critical. That is, a creditor whose claim arises after the transfer generally must show that the transferor intended to keep assets out of the creditor’s reach. Because intent may be difficult to prove, "badges of fraud" have been identified and articulated as evidence of intent.

"Badges of fraud" are fact patterns that frequently accompany fraudulent transfers. Generally, no single badge of fraud is conclusive in and of itself, but more than one badge of fraud, considered together, may lead to an inference of fraud. Commonly recognized badges of fraud include the following:33

(1) The debtor retained possession or control of the transferred property after the transfer.

(2) The debtor transferred substantially all of his or her assets.

(3) The transfer occurred shortly before or shortly after a substantial debt was incurred.

(4) Before the transfer was made or obligation was incurred, the debtor was sued or threatened with suit. PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 5

c. Unknown Future Creditor. An unknown future creditor is a creditor whom a client cannot reasonably foresee; for example, a party injured by the client in an auto accident at some future date, and for which accident the client is found liable. The courts have typically focused on protecting only those creditors whose claims are proximate in time to the asset transfer. Unknown future creditors removed in years and in events from the asset transfer have generally not been protected by the courts.34

3. WHAT CREDITORS SHOULD BE PROTECTED? Nowhere is it written that an individual must preserve his assets for the satisfaction of unknown future claims and claimants. If this were not the case, inter vivos dispositions of all sorts would be prohibited, be they gifts to children or friends, charitable contributions, or the settlement of trusts for the benefit of others. As Clifton B. Kruse, Jr. has said,35 “In order to establish that a conveyance is in fraud of creditors, there must be evidence that creditors exist (or creditors who could be reasonably anticipated) who could be defrauded. . . . Creditors alleging that a transfer was fraudulent must have, as a legal foundation for such allegation, an obligation that was present or not so remote as to have been foreseeable, to be other than a future possible creditor of an alleged debtor. There must be some scent of wrongdoing evidenced by gratuitous insolvency. Planning for one’s future well-being may be distinguished from fraudulently injuring creditors.”36

Professor Danforth concurs in this analysis. “[M]ost courts are unwilling to void transfers whose purpose and effect is to shelter assets from creditors that were unknown at the time of the transfer.”37 Professor Danforth also cites the writings of Professor Peter A. Alces, who argues for a “causal link”38 between an asset transfer and the injury allegedly suffered by a creditor:

[t]he focus on causality provides a means to distinguish between the actions that operate directly to prejudice a particular creditor and those actions that in some remote, not foreseeable way, have after the passage of considerable time or the occurrence of an intervening cause, compromised a creditor’s financial interest.39

The debate between advocates of creditor’s rights and advocates of asset protection can, and should, ultimately depend on which creditors are protected. The most serious and difficult challenge in this regard is to distinguish between a potential subsequent creditor and an unknown future creditor. That determination will always call for the exercise of the estate planner’s professional judgment, not unlike the “hard calls” involved in tax planning. Despite numerous and flagrant abuses in tax planning, no one has yet called for an end to tax planning. In the same way, though there have been abuses of asset protection planning tools and methods, that should not end the right to asset protection planning for those clients who are willing to play by the rules. PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 6

D. Proper Planning40

The proper approach to effective, careful asset protection planning begins with a solvency analysis of the client.

In an accurate solvency analysis, the lawyer should make a complete list of all of the client’s assets and then make three subtractions from the total value. The first subtraction should be the value of all current debts. Reserves must be established to satisfy these obligations. This action protects present creditors.

The second subtraction should include all liabilities, claims, contingent liabilities, threats, guarantees, contingent claims, pending lawsuits, and potential claims faced by the client. The lawyer should aggressively identify, document and quantify all of these liabilities. To assist in this exercise, it may be appropriate to conduct independent internet database research of the client’s financial/legal situation. In some cases, an audited financial statement is very helpful and should be secured. Furthermore, the attorney should inquire about the client's business and professional reputation. For example, does the physician client have a history of malpractice claims? Does the business client have a history of disputes with creditors, associates, etc.? After all liabilities are evaluated and summed, reserves must be set aside to satisfy them. This action protects potential subsequent creditors.

The third subtraction in the solvency analysis involves all client assets already protected from creditors under the law (e.g., homestead, insurance, and retirement plans). Such exemptions and protections vary tremendously from state to state, of course. In some cases, it may be advisable to join an attorney from another state (if that is where some assets are located) and/or join an attorney with creditor’s rights expertise (if there are pending claims against the client) as co- counsel.

Finally, at the end of the solvency analysis, the lawyer must devise a methodology to protect creditors. Indeed, that “creditor protection plan” is the entire purpose of the solvency analysis and is, in fact, the linchpin of prudent, careful asset protection planning.

For example, assume a client with the following assets and liabilities:

$ 20,000,000 total assets - 2,000,000 current debts - 3,000,000 claims, guarantees, contingent liabilities, threats, etc. (fully researched and quantified) - 4,000,000 protected assets, e.g., ERISA plan, homestead, annuities, life insurance $ 11,000,000 Unprotected net worth

The first element of the “creditor protection plan” is to set aside reserves sufficient to fulfill obligations to all present creditors and potential subsequent creditors ($5,000,000 in this PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 7 example). At this point, if the solvency analysis has been done thoroughly and correctly, then theoretically it is possible to do asset protection planning with the entire remaining unprotected net worth of $11,000,000. Such a course may, however, be unwise. In the event of a later challenge, the client will need to be able to demonstrate with some certainty that a reasonable margin of solvency existed at the time of any asset protection planning-motivated asset transfers. Planning with the full $11,000,000 by definition takes the client to the brink of insolvency.

Instead, lawyers and advisors should consider the concept of “Nest Egg” planning.41 The core idea of this technique is to plan with only a portion of the unprotected net worth available, leaving substantial wealth in the client’s hands and available to address the “unknown future creditor” problem.

In all events, a solvency analysis should be performed both before and after the asset protection plan is implemented. It is imperative to be able to demonstrate solvency both prior and subsequent to execution of the plan. Such an approach completes a conservative, defensible “creditor protection plan” and will make it extremely difficult for any claimant to sustain a fraudulent transfer argument. Again, an analogy to tax planning is appropriate: Always remember, pigs get fat and hogs get slaughtered.

E. Conclusion

Critics of asset protection planning are basing their resistance to such planning on arguments from the past without fully engaging the realities and client needs of the present. The law is alive. It evolves as times change, and “the times they are a changin’.” We live in an era of unprecedented litigation and litigiousness.42 The federal government, through ERISA, has explicitly sanctioned the concept of self-settled spendthrift trusts. Justice Scalia in the Grupo Mexicano case43 has all but blessed asset protection planning. Even the most outrageous asset protection trust cases, like Anderson, are being won or settled on terms generous to settlors.44 And last, but certainly not least, there is tremendous client demand for asset protection strategies that will preserve wealth against attacks from unexpected quarters in a world grown more uncertain than ever before. Whether the source of that demand is an echo of 9/11 fears, recent corporate scandals and the new emphasis on accountability in the corporate world, the liability insurance crisis, paranoia fed by asset protection marketers, or just simple foresight and prudence, clients want asset protection planning.

A major asset protection planning tool is the asset protection trust, the sort of trust that has historically often been an “instrument of tax reform” – especially when the laws require modernization.45 There are by some counts over sixty offshore jurisdictions with asset protection and asset protection trust legislation on the books. Eight states of the United States have adopted asset protection trust legislation which makes the self-settled spendthrift trust a reality in this country. Asset protection planning opportunities and techniques are readily available for our clients. It is incumbent upon us to help them take full advantage of those opportunities. PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 8

III. DOMESTIC STRATEGIES46

A. Introduction: Multiple-Entity Planning

1. DEFINITION. To help clients protect their wealth from potential creditor claims and possible future judgments, sophisticated attorneys engage in "multiple-entity" planning through the use of limited partnerships, corporations, various trust arrangements, foundations, retirement plans, life insurance and the like which, while perhaps originally conceived for the purpose of tax planning or wealth transfer, have the additional benefit of asset protection.

2. THEORY. "Multiple-entity" planning dictates that wealth should be segregated and placed in isolated, sheltered legal compartments.

3. METHODS. Opportunities for asset protection planning abound in domestic legal vehicles such as corporations, limited partnerships, limited liability companies, limited liability partnerships, trusts, retirement plans, life insurance, annuities, homesteads, spousal arrangements, inheritances, and foundations. Permutations and combinations of these entities and variations of the law between jurisdictions offer even more opportunities. For example, passive assets can be segregated from those with liability exposure (e.g., marketable securities can be segregated from an apartment complex); certain entities may be separated into multiple entities in order to achieve superior asset protection (e.g., two limited partnerships can be created to hold two pieces of real estate, each of which has an inherent risk or liability); limited partnerships can be deployed in conjunction with trusts; and corporations or limited partnerships can be formed in hospitable jurisdictions such as Delaware and Nevada.

4. LAWS OF THE STATES. The laws of the fifty United States vary markedly in what they offer by way of creditor protection.47 Recent attention has focused on Alaska and Delaware, and, to a lesser extent, Nevada, Utah, Rhode Island, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Missouri, which now have statutes that purport to protect self-settled discretionary trusts from creditor attack. A discussion of possible weaknesses of these statutes (including constitutional issues raised thereby) is found at Part IV below.48 However, although opportunities for domestic asset protection planning exist in every state, the asset that is shielded in one jurisdiction may be exposed in another.

The BAPCPA may have the effect of making it more difficult for debtors in bankruptcy to take advantage of a given state’s protections simply by moving before filing for bankruptcy. The BAPCPA amends 11 U.S.C.A. § 522, which grants debtors their choice of exemptions between those provided in § 522(d) or those provided under other federal law [including the exemptions available for jointly-owned property and retirements accounts under § 522(b)(3)(B) and (C), respectively] and the state law of the debtor’s domicile. 49 Under pre- BAPCPA law, domicile was determined for state exemption purposes by the debtor’s domicile during the 180 days immediately preceding filing of the bankruptcy petition. The BAPCPA expands this period to 730 days (two years). Alternatively, if the debtor has not been domiciled in the same state during the preceding 730 days, domicile will be the state where the debtor was PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 9 domiciled during the 180-day period preceding the 730 day period, or for the longer portion of such 180-day period if debtor resided in more than one place. Finally, if under the BAPCPA rules the debtor does not qualify as a domiciliary of any state, then he or she may opt for the federal exemptions under § 522(d).

The most obvious effect of these new provisions will be to prevent a debtor from moving on the eve of bankruptcy in the hopes of taking advantage of more favorable state exemptions. However, consider Debtor who resided in State A for six months before moving to State B, where he resided for two months. From State B, Debtor moved to State C, where he resided for one year, then to State D, where he resides when he files for bankruptcy one year later. Under this scenario, Debtor’s domicile for § 522 purposes would be State A, even though he resided in three other states since living in State A and he resided in two of those states for a longer period than in State A. Of course, whether this change benefits or hurts Debtor will turn on whether State A provides strong exemptions or weak ones.

B. Homestead

Most of the jurisdictions in the United States have enacted protective legislation for the homesteads of domiciliary debtors. The value and acreage amounts that are protected vary widely from state to state. For instance, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and the District of Columbia provide no protection whatsoever for a debtor's residence, while Texas and Florida protect up to 200 rural acres and 160 rural acres (and 10 urban acres and one-half of an urban acre), respectively, with no value limitation on the land or improvements. However, even in those states that have generous homestead protections, the homestead is not completely exempt from the claims of all creditors. Several types of claims are uniformly allowed against otherwise exempt homesteads. These claims include claims for purchase-money debt, claims for money lent to construct or make improvements to the homestead, claims for ad valorem taxes on the homestead property, and, in many cases, federal statutory liens such as federal income tax liens. Other commonly allowed claims are those for mechanic's, materialman's, and workman's liens, and any liens created by the grant of a valid security interest in the homestead.

The BAPCPA limits the homestead exemption for debtors in bankruptcy. For debtors choosing state exemptions, the BAPCPA adds new subsections (o) through (q) to 11 U.S.C.A. § 522. Subsection (o) reduces the value of the exemption for the homestead to the extent that (1) such value is attributable to property that the debtor “disposed of” in the 10-year period preceding the petition date; (2) the debtor disposed of the property with the intent to hinder, delay, or defraud a creditor; and (3) such property or portion of property would not have been exempt on the petition date if debtor had not so disposed of it. New subsection (p) limits the value of the homestead exemption to $125,000 if the debtor acquired the homestead in the 1215-day (approximately 40-month) period preceding the filing of the petition. This provision does not apply to any amount transferred from the debtor’s prior residence to his or her current residence in the same state if the prior residence was acquired outside the 1215-day period. Subsection (q) caps the homestead exemption at $125,000 (except that it may be increased if reasonably necessary for the support of the debtor and his dependents) if the debtor: (1) is convicted of a felony evidencing that the filing of bankruptcy was abusive; or (2) owes a debt PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 10 arising from (a) violations of federal or state securities laws, (b) fraud, deceit or manipulation of a fiduciary capacity in the purchase or sale of securities, (c) violations of RICO, or (d) any other criminal act, intentional tort, or willful or reckless conduct resulting in physical injuries in the preceding 5 years.

As with all new legislation, the full effect of the changes will not be known until the courts have begun to apply them to actual cases.50 However, the effects of the homestead provisions are likely to be felt most extensively in states like Florida and Texas, which provide for unlimited homestead exemptions. Subsection (q) may be especially significant in the context of planning for directors of publicly-traded companies. However, careful long-term planning may help to curb these effects.

C. Personal Property

There are wide variations among U.S. jurisdictions regarding exemptions for personal property. Some states emphasize protecting the tools of one's trade while others focus on livestock and other farm and ranch assets. Still others focus their protection on homestead furnishings. Some of the laws are antiquated and reflect the priorities of a previous century, and some have been modernized to cover victim's reparation awards, health aids, copyrights, trademarks, and personal injury awards.51

D. Life Insurance and Annuities

The protections for life insurance and annuities reflect the relative power of the insurance lobby. As to life insurance, protection for the debtor varies depending upon pre-death versus post-death statutes, the beneficiary named, and the status of premiums. Some states deal with annuities along with life insurance and some ignore annuities altogether.

E. Income

Many states offer a wide variety of protections for wages and other income, depending on the classification of that income. Some states allow garnishment of earned income while others do not. Additionally, some protect wage replacement income such as veterans' benefits or disability income.

F. Retirement Plans

The asset protection features of retirement plans are affected by both state and federal law. In general, federal law uniformly protects the assets of qualified retirement plans from the employer's or the employee's creditors. Each state may have additional exemptions that apply to plans not covered by federal law. In addition, state protections, if any, are applicable after assets have been distributed from a qualified plan. These protections vary widely from state to state.

ERISA and the Internal Revenue Code operate to provide very broad protection of qualified retirement plans (plans within the scope of Internal Revenue Code § 401(a)--pension, profit-sharing, stock bonus or annuity plans). ERISA requires that the assets of a qualified plan PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 11 be held in a trust that is not subject to the claims of the sponsoring employer's creditors. These types of plans must also contain provisions that prohibit employees from assigning their interests in the plan. Of course, this protection does not insulate the plan assets from the claims of a spouse, former spouse, or child under a qualified domestic relations order. ERISA provides no protection for nonqualified deferred compensation plans or individual retirement accounts.

Due to the significant amounts that many people accumulate in qualified retirement plans today over their working lifetimes and beyond, these exemptions are extremely important. The presence or absence of a state statute protecting individual retirement accounts might be a significant factor for a retiring participant considering whether to leave retirement plan monies in a qualified retirement plan on retirement, or to roll them over into an IRA. The variation in the protection afforded IRAs among the states might also be a factor in this decision for a relocating retiree.

Section 522(d)(10)(E) of the Bankruptcy Code exempts payments from certain retirement plans to the extent reasonably necessary for the support of the debtor and his or her dependents, but courts have been split for some time as to whether IRAs were covered under this provision. As a result of this split and the more favorable exemptions available under some state laws, debtors have often opted for state law protection for IRAs, where available. In April 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court decided Rousey v. Jacoway,52 which resolved a three-way split among federal circuit courts by unanimously holding that IRAs are covered under § 522(d)(10)(E). The significance of the Rousey decision will likely be limited by the enactment of the BAPCPA that same month, which adds new subsections (b)(3)(C) and (d)(12) to § 522. These new provisions expressly exempt IRAs for debtors who elect state exemptions or federal exemptions, respectively. New subsection (n) caps the exemption, however, at $1 million, exclusive of amounts attributed to qualified rollovers. It appears that the cap under subsection (n) will apply to limit the exemption, whether taken under subsection (d)(12) or state law.53 The cap may make other planning tools more attractive. For example, SEPs and SIMPLE-IRAs are expressly excluded from the $1 million cap. Individuals who qualify to participate in 403(b) and 457 plans may want to roll large IRAs into those plans because such plans are not capped. Furthermore, because of the unlimited exemption for rollover contributions, it may be a good idea to keep IRAs funded with rollover contributions separate from those funded with annual contributions.

The BAPCPA also added new subsection (b)(4) to § 522, creating a presumption that retirement funds that have received a favorable ruling of qualified status from the IRS may be exempted from the bankruptcy estate. On the other hand, funds that have not received a favorable determination will be exempt if the debtor establishes that a court or the IRS has not issued a contrary ruling and either that the funds have been administered in substantial compliance with Internal Revenue Code or that the debtor was not responsible for any such failure to comply. Subsection (b)(4)(C) provides that rollovers from one exempt fund to another will not lose exempt status. Finally, subsection (b)(4)(D) permits an exemption for either “eligible rollover distributions” [as defined under IRC § 402(c)]54 or distributions from certain qualified plans that are rolled over into another qualified plan within sixty days. PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 12

G. Federal Statutes

A number of federal statutes protect individual assets: one law, for example, protects a seaman's clothing, while other laws shelter trillions of dollars in retirement plans. The federal government protects certain benefits derived from military service; for example, the pension of a Medal of Honor recipient cannot be attached or garnished.

H. College Savings Plans

Federal law allows states to create college savings plans in which the income earned may be effectively tax-free if used for certain educational expenses. These plans are commonly open to participation by residents and non-residents alike, so that everyone can shop all plans available in the U.S. to determine what plan best fits a student’s needs. Most state statutes creating these plans provide the assets in the plan with some protection from the claims of the owner’s or beneficiary’s creditors. However, there is some question as to how effective these provisions may be for residents of other states. For this reason, care should be taken to examine the exemptions available in the state of residence, as well as the state sponsoring the plan.

The BAPCPA amended 11 U.S.C. § 541 to exclude from the bankruptcy estate certain education IRAs and tuition plans under §§ 529 and 530 of the Internal Revenue Code. In general, these funds must benefit a child, stepchild, grandchild, or step-grandchild of the debtor. The exclusion for § 529 plans is limited to (1) funds not exceeding the contribution limits of § 529 (amount necessary to provide for the beneficiary’s education expenses) that were contributed not later than a year preceding filing of the petition, and (2) $5,000 for all such accounts having the same designated beneficiary during the period between 1 year and 2 years preceding the petition date. The exclusion for education IRAs is limited to (1) funds not exceeding the contribution limits of § 4973(e) ($2,000 or less) that were contributed not later than a year preceding filing of the petition, and (2) $5,000 for all such accounts having the same designated beneficiary during the period between 1 year and 2 years preceding the petition date. The effect of these provisions is to include in the bankruptcy estate the amounts not qualifying for the new exclusions. However, these amounts may be pulled back out of the estate as exempt if the debtor opts for state law exemptions under § 522 and the debtor's state protects such contributions from creditors. The BAPCPA also amends § 521 to require a debtor (the “contributor” under §§ 529 and 530) to file a notification of an interest in an education IRA or qualified state tuition program.

I. Joint Property Ownership

Another simple domestic asset protection strategy involves the structuring of property ownership. Joint ownership of property provides little theoretical protection from creditors. However, as a practical matter, certain joint ownerships effectively discourage creditors. Even switching from a co-tenancy to a joint tenancy can provide a modest improvement in asset protection. PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 13

J. Marital Property Positioning

1. GENERAL RULES OF MARITAL PROPERTY LIABILITY. The rules of liability for debts of a married couple depend on when the debt was entered into, what kind of debt is at issue, and what kind of property is at issue. The first question is which spouse has liability for the debt. In general, one spouse has no liability for the debts of the other spouse unless the spouse is liable under other rules of law, or one spouse acts as agent for the other. Both spouses are generally liable for debts for necessaries. Once spousal liability has been determined, the availability of each type of property is considered. One spouse’s property should not be subject to another spouse’s debts. However, especially in community property states, the liability of marital or community property for one spouse’s debts may be an issue.

2. MARITAL PROPERTY PLANNING. Planning for appropriate ownership of marital property can have important asset protection benefits. Of course, any marital property planning that has as its goal asset protection will have far-reaching implications to each spouse. It will alter the spouses’ rights with respect to their property, including the spouses’ rights to property in the event of divorce, and the division of property on death. Changing community property into separate property will allow only one-half of the property to receive a step up in basis at one spouse's death (whereby the basis of the property for capital gain purposes is deemed to be its value on the date of death, rather than the purchase price), whereas under current law, all of the community property will receive a step up in basis at one spouse's death. Due to these wide-ranging implications, it is preferable for each spouse to have separate legal counsel in marital property planning situations.

a. Books and Records. The most important step in any marital property planning is that the parties keep good books and records concerning the ownership of their property. The danger is that the different types of property unintentionally may become mixed together and lose any asset protection benefits that may be available. If only one spouse is to be liable for a specific debt, the spouses should take care in their representations to any potential lender that they do not lead the lender to believe that the other spouse's property may be available to satisfy the debt.

b. Marital Property Agreements. Spouses generally can change the nature of their marital property through premarital agreements or marital property agreements. These agreements can directly affect what property will be available to satisfy a creditor's claims by changing the ownership of the property. Sometimes the purpose behind these arrangements is to allocate all of the property to the spouse with the least creditor exposure. In other cases, the goal may be simply to divide the property equally, so that only half will be subject to the claims of the creditors of one spouse.

c. Gifts Between Spouses. Another way to accomplish the allocation of property to one spouse is for the spouses to make gifts to each other. A marital property agreement specifying that the gift has taken place and addressing the future income from the gifted property may or may not be done in conjunction with such a gift. Any such gifts between PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 14 persons contemplating marriage should be done after marriage, so that the marital deduction will be available and the gift will not be subject to gift tax.

Achieving asset protection by shifting the ownership of assets between spouses involves a determination as to which spouse is the most likely to be subject to creditors’ claims, which is always a gamble with varying degrees of risk (depending mostly on the parties' professions). However, when that shifting is done by means of gifts, the spouse making the gift can create a trust for the benefit of the other spouse, thereby shielding the assets from the claims of both spouses’ creditors.55 The use of trusts also allows the gifting spouse to retain some control over the ultimate disposition and management of the assets.

d. Tenancies by the Entirety. In states where ownership of property as tenants by the entireties is possible it may provide significant asset protection benefits. This form of joint property ownership, available only between married persons, generally protects property from the claims of one spouse’s creditors. When one spouse dies, the other takes the property free of the first spouse’s debts. However, this protection is available only so long as the parties are married. Once the property is wholly owned by one spouse, the property may be reached by that spouse’s creditors. Similarly, if the property is converted into some other form of joint ownership, each spouse’s portion will be subject to his or her debts.

K. Business Arrangements—General

1. LIABILITY ASSOCIATED WITH SPECIFIC ACTIVITIES. Individuals are often engaged in activities that have inherent liability risk, such as the ownership of real property. By placing the activities that generate these risks into a limited liability vehicle, such as a corporation, a limited liability company, or a limited partnership, the client can insulate, to some degree, the rest of his wealth from liabilities associated with the activity. The choice of the specific entity will depend on an analysis of the complexity of administration of each business structure, the exposure of the activity and the entity to the state taxes, and the client's estate planning goals with respect to the property. The shareholders of a corporation and the members of a limited liability company are not liable beyond their investments for claims arising out of the activities of the entity. Limited partners in a limited partnership have a status similar to that of shareholders in that regard. However, a limited partnership must have a general partner whose liability is not limited in this respect. Therefore, if this type of asset protection is desired, the general partner should not be an individual, but a limited liability company or corporation.

2. OTHER THREATS TO WEALTH. Contribution of assets to family- owned business entities may also provide some protection from an owner's general creditors. Creditors of an individual owner of an interest in a business entity generally have access only to that interest, not the assets of the entity. Any interest in a family-owned business entity will be subject to the claims of the creditors of the owner of that interest to some degree. However, ownership of such an interest may not be appealing to a creditor, which may be a factor influencing settlement of a case. There are two key reasons that such ownership may be unappealing. First, it may be a minority interest that gives the creditor little or no control over PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 15 the manner in which the business is run. In addition, it may not be marketable, either due to transfer restrictions or simply because no buyers are willing to buy the interest. These are, of course, the same features that depress the value of interests in these entities for federal estate and gift tax purposes. The key feature of both of these "discounts" in value for interests in a business entity is ownership by multiple parties. In general, the more control an individual party has over the business entity, the more exposed the entity is to the claims of the individual's creditors.

a. Corporations. Corporations are probably the least effective of business entities in this regard. If a creditor seizes shares of a corporation, the creditor may exercise all of the rights of a shareholder. These rights may not be significant to the creditor if he or she has a small minority interest. If there are multiple owners of a corporation, some protection may still be available if the seizure triggers a buy-sell agreement that has been previously negotiated.

b. Limited Liability Companies. Limited liability companies, on the other hand, have significant asset protection features. These features vary on a state by state basis. Membership in a limited liability company is personal to the individual member. Only members or their designated managers have a voice in management of a limited liability company. A judgment creditor may petition a court for a charging order against the interest of a member in a limited liability company, so that the creditor has a right to receive distributions with respect to that member's interest and rights to certain information. The creditor has no right to become a member. The creditor may be subject to income taxes on the income attributable to a membership interest, even if it is not distributed.56

These rules are designed to protect the members of a limited liability company from the interference of an uninvited third party. As such, the degree to which they will be respected if the limited liability company has only one member is still being determined by the courts. A limited liability company with only one member may not be afforded the same types of protection as a company having multiple members.

c. Limited Partnerships. Limited partnerships also offer some asset protection features. Limited partners by their nature do not have rights in the day-to-day management of the partnership; this authority rests with the general partner. Typically, in a family-owned entity, there are also significant restrictions on the ability to transfer limited partnership interests. However, a creditor of a limited partner has even fewer rights than the limited partner himself.

Under most state statutes, a judgment creditor of a partner may petition a court for a charging order with respect to a limited partner's interest in the partnership, which gives the creditor the right to receive any distributions that would otherwise be made to the debtor/partner. Under some circumstances and in some states, the creditor may actually be able to obtain the underlying partnership interest, which also gives the creditor the status of an assignee. Assignees of a limited partner's interest have even fewer rights than limited partners have; they have only the rights to share in PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 16

distributions to the extent the general partner chooses to make them. However, the assignee is subject to income taxes on the income earned by any pass-through entity, whether received or not. They cannot become limited partners without the approval of all of the other partners (or pursuant to any other procedure specified in the partnership agreement). Even if a creditor is able to sell the interest to a third party, he will likely have to discount the price substantially (if he can find a buyer in the first place) due to the lack of control and illiquidity that characterize interests in limited partnerships.

The general partner's role in a limited partnership is critical. If an individual is a general partner and his interest is alienated, it is generally treated as a withdrawal from the partnership. The general partner's interest may be converted to a limited partnership interest or may be purchased by the partnership or the other partners upon a vote by the limited partners. If any general partners remain, the partnership is continued if the agreement so provides. If no general partners remain, the limited partners may vote to continue the partnership and appoint a new general partner. The presence of more than one general partner is therefore important. If the general partner is a corporation or limited liability company, ownership by multiple parties is important so that the creditors of one party cannot gain control over the general partner and thereby the partnership.

3. RESPECTING THE BUSINESS ENTITY. With each kind of business entity that might be used for asset protection purposes, protecting the integrity of the entity is important. The creditor's argument is basically "why should I be forced to respect the structure of the entity, if the owners have chosen not to?" In the corporate context, this theory has been used to impose liability on the shareholders for a corporation's debt, and is known as "piercing the corporate veil." This traditional concept of piercing the corporate veil is also being used by courts to ignore the business entity and allow the creditors of an individual owner to access assets owned by the business entity. This “reverse-veil piercing” theory is being used against corporations, limited partnerships, and limited liability companies. As illustrated by one leading case in this area, C.F. Trust, Inc. v. First Flight Limited Partnership, 580 S.E. 2d 806 (Va. 2003), the courts’ decisions are heavily influenced by the individual facts of each case, as well as the court’s overall impression of the equities involved.

As a practical matter, this issue is not as serious for limited liability companies and partnerships as for corporations, simply because there are fewer formalities to be observed. However, preserving the financial life of these entities separate and apart from that of their owners is critical to their success as asset protection vehicles. For this reason, owners should avoid such obvious pitfalls as paying personal expenses from business accounts, or having a business entity own a primary residence which a member or partner is allowed to use rent-free.

L. Gifts, Trusts, and Disclaimers

Many U.S. asset protection opportunities exist in the traditional estate planning areas of gifts, trusts, and disclaimers. While state statutes differ in their treatment of disclaimers (in some PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 17 states it can be a fraudulent transfer and in others it is not, even with an existing creditor), old- fashioned estate planning through gifts and trusts enables many patriarchs and matriarchs to insure the financial future of successive generations. Surprisingly, however, many states ignore or dilute the protection afforded by "spendthrift" clauses.57 Therefore, a practitioner's knowledge in this area might lead to the conclusion that forum shopping within the fifty United States is appropriate even for life insurance trusts, "Crummey" trusts, and other commonplace estate planning trusts.

1. TRUSTS: ASSET PROTECTION CHECKLIST. Leaving assets to a beneficiary in trust has been the traditional method of shielding the assets from the claims of the beneficiary's creditors, or saving the beneficiary from himself. Although the use of trusts is currently being pursued in many new contexts, the traditional spendthrift trust remains the most common asset protection planning device.

a. "Spendthrift" Protection. A spendthrift trust is one that contains a provision prohibiting the beneficiary from assigning his interest in the trust, and also prevents a beneficiary's creditors from reaching the beneficiary's interest. Spendthrift provisions are respected as being within the power of a donor to place conditions on any potential gifts. This principle does not extend to the individual himself - the large majority of American jurisdictions adhere to the traditional rule that a person cannot shield his own assets from the claims of his creditors.

Because a person cannot effectively place assets in a spendthrift trust for his own benefit, identifying who created the trust and transferred assets to it is important for asset protection purposes. A person who is entitled to receive funds but requests the payor to pay the funds to a trust will be considered the settlor of that trust. If two people create identical trusts for each other, under the “reciprocal trust” doctrine, each will be considered as creating his or her own trust. Finally, a beneficiary’s powers over the trust assets may be so extensive that the beneficiary is treated as the owner of all of the trust assets, and therefore a creator of the trust. The identification of the settlor does not stop at the names on the trust document, or even the identity of the persons who made the physical asset transfers.

b. Interest of the Beneficiary. If a creditor is able to reach assets held in a spendthrift trust, the creditor can reach only the beneficiary's interest in the trust. For this reason, defining and limiting that interest is very important.

(1) Distribution Standard. A creditor of a beneficiary will have more difficulty reaching a beneficiary's interest in a trust if distributions to that beneficiary are not fixed, but are subject to the discretion of the trustee. The broader the trustee's discretion, in general, the greater the protection. This protection is magnified if there are multiple beneficiaries among whom a trustee may "sprinkle" distributions. Finally, a beneficiary's interest in a trust may change depending on his or her circumstances. For example, a trust providing for mandatory distributions might convert to a discretionary trust if the beneficiary becomes insolvent. PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 18

(2) Powers of Appointment. Many trusts that are motivated by tax planning contain general powers of appointment which give a trust beneficiary the authority to vest trust assets in himself, his estate, his creditors, or the creditors of his estate. There is a split of authority as to whether or not a creditor may reach trust assets subject to a beneficiary's power of appointment. One line of authority is that a power of appointment is a property right, and a creditor should have all that the beneficiary may reach.58 This view is certainly the case in bankruptcy proceedings. The more common rule under state law, however, is that a power of appointment is an intensely personal right, and exercise of that power may not be forced by a creditor.

A second issue is whether or not the lapse of a power of appointment causes the trust to be a self-settled trust, thereby nullifying the effect of any spendthrift clause. A lapse of any power of appointment has this effect for income tax purposes. Lapses of powers of appointment in excess of the greater of $5,000 or 5% of the trust assets certainly have this effect for estate, gift, and generation-skipping transfer tax purposes. This question is largely unanswered in most states.

c. Duration of the Trust. One limitation on spendthrift protection is that it only applies so long as trust assets remain in the trust. Once in the hands of the beneficiary, the assets are fair game to creditors. Placing the assets in trust for as long as possible therefore has asset protection advantages. Most states still subscribe to the traditional rule against perpetuities, which states that all interests in property must vest no later than twenty- one years after the death of the last survivor of "lives in being" on the creation of the interest. Translated in practical terms, the Rule requires termination of a trust no later than twenty-one years after the death of the last survivor of a group of people who are living when the trust is executed. Several American jurisdictions have modified this rule or abolished it altogether.

d. Selection of the Trustee. Appointment of a trustee who is not a beneficiary of the trust is generally preferable for asset protection purposes. At common law, if the trustee was also the sole beneficiary of the trust, equitable and legal title to the trust assets were "merged," and the trust was disregarded. This rule has been eroded to a significant degree. For example, many state statutes provide that a spendthrift trust is by definition not subject to the merger doctrine. In addition, many courts have held that any interest, even a remote, contingent interest, held by any other beneficiary, will defeat the doctrine of merger. However, separation of these two roles continues to be the most effective course for asset protection. Recently, the authors of the Restatement (Third) of Trusts seem to have embraced a position that spendthrift provisions may be weakened or undermined when the beneficiary of a discretionary trust is also the trustee.59 Although this view has not been widely accepted, if a beneficiary is also a trustee, a creditor can more easily make arguments that the trust should be disregarded due to a beneficiary’s lack of observance of the trust terms, or easy availability of trust assets.

e. Threats to Assets Held in Trust.

(1) Limits on Spendthrift Protection. The most serious limit on spendthrift protection has already been discussed; that being that the protection only exists so PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 19 long as the assets remain in trust. However, there are other common limitations. For example, state law may allow child support payments owing by a beneficiary to be recovered from a trust, but only to the extent the trustee actually makes distributions from the trust. In addition, a creditor who provided necessaries to the beneficiary may be able to reach those trust assets that the trustee would apply for the beneficiary's support in the exercise of reasonable discretion.

In a few states, limitations on spendthrift protection are more extensive. Spendthrift clauses may protect only a certain amount of trust assets in some states. Or spendthrift trusts may be vulnerable to claims for child or spousal support, or claims by the state or the United States. A few states allow tort creditors of a beneficiary to reach spendthrift trust assets.

The presence of this wide divergence in trust law underscores the importance of the question of which law applies. When the settlor, beneficiary, and trustee live in different states, the question of which state law will apply to a creditor's claim will depend on the trust terms and the nature of the trust question at hand. Although a trust may specify the state's law that is to be applied in interpreting a trust, these types of directions may not be respected in all cases or with regard to all questions, especially if that state has no other connection to the trust.

(2) Disregarding the Trust. Sloppy record-keeping and a trustee commingling its personal assets with those of the trust can seriously undermine any asset protection that would otherwise be afforded to trust assets. This danger is particularly acute if the beneficiary is also the trustee and has failed to segregate personal assets from trust assets. Even though courts are reluctant to disregard spendthrift protection, and any such errors would be a breach of trust, an inability to demonstrate that a real trust exists may place the assets in jeopardy, especially in the divorce and bankruptcy contexts.

2. ASSET PROTECTION IMPLICATIONS OF COMMONLY USED ESTATE PLANNING TRUSTS.

a. Credit Shelter Trusts/Bypass Trusts. Probably the most commonly used type of trust in estate planning is a trust created at the death of one spouse for the benefit of the surviving spouse to utilize the deceased spouse’s unified credit against estate and gift taxes. This amount today shelters the first $2 million of a person’s assets from estate tax. For example, a person’s will might provide that $2 million will pass to a trust for the benefit of the surviving spouse. The trust assets will be sheltered by the deceased spouse’s estate tax exemption and will not be subject to estate tax at the surviving spouse’s death. The very features that cause these trusts to escape estate tax at the surviving spouse's death make them effective asset protection vehicles. For maximum asset protection, an independent trustee should be appointed, and distributions should only be made in the trustee’s discretion.

Spouses can also create these types of trusts while they are alive. Making large lifetime gifts is a very effective estate planning tool because it allows all future income and appreciation to escape estate and gift tax. However, many individuals are not quite ready to PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 20 completely remove large sums of money from the pool of assets that might be available for their support in the future. In this situation, one spouse can create a trust that is available for the other spouse’s support if needed. Any remaining assets will pass tax-free to the couple’s children at the spouse’s death. In this way, both tax planning and asset protection goals may be achieved.

b. Marital Deduction Trusts. Many people today are reluctant to make gifts that require the payment of gift tax. Today, the exemption from estate tax is $2 million, yet only $1 million of this amount may be applied towards lifetime gifts. With exemptions from estate tax on the rise, it may very well be that the client’s assets will not be subject to estate taxes at his death. Once a client has given away his full exemption from gift tax, if further gifts to a spouse are desired, a marital deduction trust should be considered. These types of trusts can be created at the death of one spouse, or during both spouses’ lifetimes. Gifts to this type of trust generate no gift or estate tax when the trust is created. For this reason, the terms of these trusts are largely governed by the Internal Revenue Code. All income must be paid to the spouse/beneficiary. To the extent the spouse/beneficiary receives this income, spendthrift protection is lost, unless some other state exemption applies.60 However, principal can be accumulated or distributed in the trustee’s discretion. The trust assets are subject to estate tax at the spouse/beneficiary’s death. However, the trust assets should not be subject to the claims of the spouse/beneficiary’s creditors.

c. Generation-Skipping Trusts. Trusts that are designed to be preserved for several generations, or generation-skipping trusts, are generally designed to avoid estate tax at the passing of each generation. For example, a parent might create a trust for a child’s benefit that would last for his lifetime, with the remainder passing to the child’s children. The trust would be structured so that it would not be subject to estate tax at the child’s death, thereby “skipping” a generation of tax.

There is a generation-skipping transfer tax that applies when assets “skip” a generation of taxes in this way. However, each person has an exemption from this tax, which is currently $2 million. So, a parent could place $2 million in this type of trust today, and the trust, including all growth of the trust assets, would be protected from estate tax, the generation- skipping transfer tax, and the claims of the beneficiary’s creditors.

Once the $2 million limit is reached, additional assets may be placed in trusts that last for the beneficiary’s lifetime. These trusts should be structured so that they are subject to estate tax or generation-skipping transfer tax at the death of the member of the second generation (i.e., the child of the donor). However, all of the other asset protection features available to generation-skipping trusts are available to these types of trusts as well.

Other general principles of trust law are important here as well. For maximum asset protection, a beneficiary should not be the sole trustee. Distributions to the beneficiary should be made in the trustee’s discretion. Formalities of the trust must be observed. However, the spouse of the donor may be a permitted beneficiary of the trust if this type of safety net makes the donor more comfortable in making these gifts. PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 21

d. Crummey Trusts. Each person may give up to $12,000 per year to as many people as he wishes without gift tax. Persons who wish to utilize these annual exclusions from gift tax by making gifts to minors often do so by making gifts to trusts. Crummey trusts give the beneficiary a power to withdraw the amount of any gift made to the trust, which lapses if unexercised after a short period (often thirty days). This withdrawal power allows the gift to be subject to the annual exclusion.

The property subject to the withdrawal power is vulnerable to creditors during the period it exists. Whether or not the lapse of a withdrawal power has adverse asset protection consequences is an open question in most states.61 Although the asset protection exposure is generally limited with these types of trusts, it can become larger if "hanging" powers of withdrawal are used. These powers of withdrawal lapse only to the extent of the greater of $5,000 or 5% of trust assets per year, while the rest of the property continues to be subject to the power. This amount can grow quite large over a period of years, and it continues to be vulnerable as long as the power exists.

e. Life Insurance Trusts. Life insurance trusts are commonly structured as Crummey trusts. However, the investment of trust assets in life insurance may be a factor that increases the asset protection available for assets in these trusts.

f. Charitable Remainder Trusts. Charitable remainder trusts provide for the payment of a fixed amount (a percentage of the trust assets or a fixed dollar amount) to a beneficiary for a specified period of time, followed by a payment to charity at the trust's termination. These trusts allow the donor to obtain a charitable income tax deduction for the value of the charity’s interest at the time the trust is created. The trust itself is not subject to income tax. Taxes are paid by the beneficiary as funds are received from the trust.

The fact that the payment is fixed reduces the asset protection available to a beneficiary, since a trustee generally has no discretion to accumulate the distribution rather than pay it to the beneficiary, unless some other state exemption would protect these payments. 62 In contrast, if a person creates a charitable remainder trust for his or her own benefit, some asset protection might be achieved. The settlor’s interest in the trust would generally not be protected by a spendthrift clause. However, the settlor's only interest in the trust would be the right to the fixed payments; the corpus of the trust would be protected. In states that allow self-settled spendthrift trusts (see Part IV below), it may be possible to protect the settlor’s undistributed interest in a spendthrift trust.

g. GRATs, GRUTs, and QPRTs. GRATs and GRUTs are creatures of the tax code. A settlor who establishes a GRAT or a GRUT retains the right to a payment of a fixed amount (a percentage of the trust assets or a fixed dollar amount) for a specified period of time, after which the assets pass to another party. The value of the settlor’s gift is the present value of the remainder interest on the day the trust is created. There is the potential for large value shifts if the trust “beats” the rate of return used to determine the value of the remainder interest when the trust is created. By definition, GRATs and GRUTs are self-settled trusts, and therefore, a spendthrift provision generally will not prevent a creditor from seizing the settlor's PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 22 interests in them. The settlor's interest is the stream of payments that he retains when the trust is established. Like the charitable remainder trust, because the settlor's interest is fixed, the entire trust corpus cannot be reached by his or her creditors, and the settlor may actually achieve some asset protection that he would not have if he owned the assets outright. In states allowing self- settled spendthrift trusts (see Part IV below), additional protection for the settlor’s interest may be achieved. The settlor’s creditors can reach the payments he receives unless some other exemption applies.

In a QPRT the settlor transfers his residence to a trust and retains the right to live there for a specified period of time. At the end of the term, the assets generally pass to the settlor’s children. The value of the settlor’s gift is the present value of the children’s future right to the home on the day the trust is created. In this way, a 50 year old person could give away a $1,000,000 home at a gift tax value of $150,000. The settlor's retained right in a QPRT is merely the right to live in the residence during the term. An argument can be made that this type of right is personal and cannot be seized by a creditor. Consideration should be given as to whether contributing a residence to a QPRT affects the settlor's homestead exemption. In fact, the QPRT is often used in states where no (or limited) homestead protection is otherwise available to shelter homestead assets. It could also be used to provide some asset protection for a vacation home that would not be classified as a "homestead."

IV. DOMESTIC VENUES FOR ASSET PROTECTION TRUSTS63

A. Introduction

Alaska, Delaware, Nevada, Utah, Rhode Island, Oklahoma, South Dakota and Missouri (the "Domestic Venues")64 have enacted legislation with a view toward becoming viable venues for establishing asset protection trusts. Although all Domestic Venue statutes appear to offer substantial (or at least some) asset protection (especially against the claims of future creditors), none of these states can be as protective a site for establishing trusts as an offshore jurisdiction because they are a part of the United States and are, therefore, bound by the United States Constitution. By virtue of the "full faith and credit" mandate in the Constitution,65 the courts of one state must recognize judgments rendered under the laws of less debtor-friendly states. In addition (and as more fully discussed below), the enactment of laws enabling asset protection trusts may itself violate the Constitution's contract clause.66 Finally, due to the supremacy clause67 of the Constitution, no state statute can protect debtors from conflicting federal law (i.e., bankruptcy law). Even if state asset protection trust legislation passes constitutional muster, it does not necessarily defend an asset protection trust from some of the arguments available to a creditor through other existing state laws. The new statutes, existing statutory provisions, and common law provide various opportunities for a sympathetic court, whether in a Domestic Venue or elsewhere, to set aside or penetrate the trust structure in favor of creditors.68

B. Overview of Domestic Venue Asset Protection Trust Legislation

1. THE ALASKA TRUST ACT. Under the Alaska Trust Act,69 a person who transfers property to a trust may make the beneficial interests subject to spendthrift PLANNING FOR ASSET PROTECTION Page 23 provisions. That is, the beneficial interests are protected by provisions in the trust agreement from being alienated, either voluntarily or involuntarily, before they are distributed to the beneficiaries. Furthermore, as long as a settlor (a) did not make the transfer with an intent to defraud creditors, (b) is not in default by thirty or more days on child support payments, (c) retains no right to mandatory distributions, and (d) has no power to revoke or terminate the trust, the Alaska Trust Act will allow that settlor to be a discretionary beneficiary of such a trust and will prevent that settlor's creditors from gaining access to the trust assets.70 Thus, a settlor can protect assets from the claims of creditors by placing them in such a trust and nevertheless continue to enjoy the benefit of such assets.71

Recently, substantial legislative changes to the Alaska Trust Act have been made which were designed to increase the efficacy of the Alaskan domestic venue asset protection trust. First, the amendments to the Alaska Trust Act addressed the issue of the unlimited statute of limitations for a pre-existing creditors to set aside transfers as fraudulent, which exists as a consequence of that portion of the statute which gives a creditor one year after "discovery" of the transfer. An unlimited statute of limitations is common to all domestic venue asset protection statutes. The amended Alaska Trust Act addresses the pre-existing creditor issue by extinguishing any action to set aside a transfer to the trust as fraudulent by a pre-existing creditor unless the pre-existing creditor brings the action within the later of four years after the date the transfer to the trust is made or one (1) year after the date the transfer is discovered by the creditor if the creditor can prove (by a preponderance of the evidence) that he or she has asserted a specific claim before the transfer.72 Because the pre-existing creditor must have previously asserted the claim or must bring the action at the latest, four years after the transfer, this amendment was intended to bring a level of certainty to a settlor with potentially unknown pre- existing creditors.