Text S1: Detailed Proofs for “The Time Scale of Evolutionary Innovation”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN EVOLUTION JACK LESTER KING UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SANTA BARBARA This Paper Is Dedicated to Retiring University of California Professors Curt Stern and Everett R

THE ROLE OF MUTATION IN EVOLUTION JACK LESTER KING UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA BARBARA This paper is dedicated to retiring University of California Professors Curt Stern and Everett R. Dempster. 1. Introduction Eleven decades of thought and work by Darwinian and neo-Darwinian scientists have produced a sophisticated and detailed structure of evolutionary ,theory and observations. In recent years, new techniques in molecular biology have led to new observations that appear to challenge some of the basic theorems of classical evolutionary theory, precipitating the current crisis in evolutionary thought. Building on morphological and paleontological observations, genetic experimentation, logical arguments, and upon mathematical models requiring simplifying assumptions, neo-Darwinian theorists have been able to make some remarkable predictions, some of which, unfortunately, have proven to be inaccurate. Well-known examples are the prediction that most genes in natural populations must be monomorphic [34], and the calculation that a species could evolve at a maximum rate of the order of one allele substitution per 300 genera- tions [13]. It is now known that a large proportion of gene loci are polymorphic in most species [28], and that evolutionary genetic substitutions occur in the human line, for instance, at a rate of about 50 nucleotide changes per generation [20], [24], [25], [26]. The puzzling observation [21], [40], [46], that homologous proteins in different species evolve at nearly constant rates is very difficult to account for with classical evolutionary theory, and at the very least gives a solid indication that there are qualitative differences between the ways molecules evolve and the ways morphological structures evolve. -

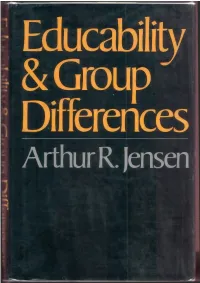

Educability and Group Differences

Educability & Group Differences Arthur R. lensen $10.00 In this pivotal analysis of the genetic factor in intelligence and educability, Arthur Jensen ar gues that those qualities which seem most closely related to educability cannot be ac counted for by a traditional environmentalist hypothesis. It is more probable, he claims, that they have a substantial genetic basis. Educabil ity as defined in this book is the ability to learn the traditional scholastic subjects, especially the three R's, under ordinary conditions of class room instruction. In a wide-ranging survey of the evidence, Professor Jensen concludes that measured IQ is determined for the most part by an individual’s heredity. He reasons that the present system of education assumes an almost wholly environ mentalist view of the origins of individual and group differences. It is therefore a system which emphasizes a relatively narrow category of human abilities. While the existing body of evidence has many gaps and may not compel definitive conclusions, Dr. Jensen feels that, viewed all together, it points strongly and consistently in the direction of genetics. 0873 THE AUTHOR Since 1957 Dr. Arthur R. Jensen has been on the faculty of the University of California in Berke ley. where he is now Professor of Educational Psycholog) and Research Psychologist at the Institute of Human Learning. A graduate of U.C., Berkeley, and Columbia University, he was a climca psychology intern at the University of Maryland Psych atric Institute and a postdoc- tora 'esea^ch feijow at the Institute of Psychia try, Unrversity of London. He was a Guggenheim Fellow arvd a bellow of the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. -

Isoallele Frequencies in Very Large Populations

ISOALLELE FREQUENCIES IN VERY LARGE POPULATIONS JACK LESTER KING Aquatic and Population Biology Section, Department of Biological Sciences, University of California, Santa Barbma, California 93106 Manuscript received June 19, 1973 ABSTRACT The frequencies of electrophoretically distinguishable allelic forms of en- zymes may be very different from the corresponding frequencies of struc- turally distinct forms, because many sequence variants may have identical electrophoretic charge. In large populations such frequencies will be deter- mined largely by the number of amino acid sites that are free to vary. The number of distinguishable electrophoretic variants will remain fairly small. Beyond some limiting size, no further effect of population size on allele fre- quencies is expected, so isolated large populations will have closely similar allele frequencies if polymorphism is due largely to mutation and drift. The most common electrophoretic alleles are expected to be flanked by the next most common, with the rarer alleles increasingly distal. Neither strong selec- tion nor mutation/drift interpretations of enzyme polymorphism are yet dis- proven, nor is any point between these extremes. IMURA and CROW(1964) proposed an estimate of the number of selectively equivalent isoalleles that would be expected in a finite population at equi- librium, using a model in which each mutation is unique and in which there are therefore an infinite number of possible allelic states. Their well-known con- clusion is that the “effective number” of alleles would be ne = 1 + 4N,v where Ne is the effective population size and U is the mutation rate per generation. AYALA(1973) (AYALAet aZ. 1972) observed that this equation would predict many hundreds of neutral isoalleles in tropical Drosophila populations, which have population sizes in the billions, if one accepts the neutral allele mutation rates necessary for any significant amount of evolution by mutation and drift. -

The Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution

The Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution .. It holds that at the molecular level most evolutionary change and most ofthe variability with/n a species are caused not by selection butbyrandom drift ofmutantgenes that are selectively equivalent by Motoo Kimura Scientific American, November 1979 he Darwinian theory of evolution the methods of population genetics de ical genetics" of, E. B. Ford and his through natural selection is firmly veloped mainly by R. A. Fisher, J. B. S. school and other investigations built a T established among biologists. The Haldane and Sewall Wright. On their large and impressive edifice of neo-Dar theory holds that evolution is the re foundation subsequent studies of natu winian theory. sult of an interplay between variation ral populations by Theodosius Dob· By the early 1960's there was a gener and selection. In each generation a vast zhansky, paleontological analyses by al consensus that every biological char amount of variation is produced within George Gaylord Simpson, the "ecolog- acter could be interpreted in the light of a species by the mutation of genes and by the random assortment of genes in reproduction. Individuals whose genes give rise to characters that are best ORDOViCiAN DEVONIAN CARBONIFEROUS adapted to the environment will be the TRIAsSIC L fittest to survive, reproduce and leave 500 440 400 350 270 225 1 survivors that reproduce in their turn. MILLIONS OF YEARS AGO Species evolve by accumulating adap tive mutant genes and the characters to 11<E<~---------- PALEOZOIC -----------;.>~~lcE<---;.. which those genes give rise. In this view any mutant allele, or mu tated form of a gene, is either more adaptive or less adaptive than the allele from which it is derived. -

History in the Gene Negotiations Between Molecular and Organismal Anthropology

Research Collection Journal Article History in the Gene Negotiations Between Molecular and Organismal Anthropology Author(s): Sommer, Marianne Publication Date: 2008 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000011584 Originally published in: Journal of the History of Biology 41(3), http://doi.org/10.1007/s10739-008-9150-3 Rights / License: In Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Permitted This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library Journal of the History of Biology (2008) 41:473–528 Ó Springer 2008 DOI 10.1007/s10739-008-9150-3 History in the Gene: Negotiations Between Molecular and Organismal Anthropology MARIANNE SOMMER ETH Zurich 8092 Zurich Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. In the advertising discourse of human genetic database projects, of genetic ancestry tracing companies, and in popular books on anthropological genetics, what I refer to as the anthropological gene and genome appear as documents of human history, by far surpassing the written record and oral history in scope and accuracy as archives of our past. How did macromolecules become ‘‘documents of human evolutionary history’’? Historically, molecular anthropology, a term introduced by Emile Zuckerkandl in 1962 to characterize the study of primate phylogeny and human evolution on the molecular level, asserted its claim to the privilege of interpretation regarding hominoid, hominid, and human phylogeny and evolution vis-a` -vis other historical sciences such as evolutionary biology, physical anthropology, and paleoanthropology. This process will be discussed on the basis of three key conferences on primate classification and evo- lution that brought together exponents of the respective fields and that were held in approximately ten-years intervals between the early 1960s and the 1980s. -

OP-MOLB Spl Issue TOC 1..1

Welcome to the Annual Meeting of the Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution in Yokohama, Japan (July 8–12, 2018) This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Neutral Theory. The editorial board of Molecular Biology and Evolution has assembled this special reprint issue to celebrate the continuing impact of Motoo Kimura’s proposal of “The Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution” in 1968 and the nearly concurrent publication with a similar theme, “Non-Darwinian Evolution,” by Jack Lester King and Thomas Jukes. The Neutral Theory has had tremendous and continuing impact on the study of molecular evolution, showing immediate utility as a valuable counterpoint to strict selectionist views and as a null hypothesis that enables statistical detection of selective pressures at genomic loci. As the years have progressed, interpretations of the neutral theory have been impacted by empirical developments, including technological advances that enable rigorous investigation of hypotheses stimulated by the Neutral Theory. In parallel, theoretical refinements have affected our understanding of how population size and other demographic parameters influence our assessment of variation as neutral or nearly so, as well as our awareness that the impact of genetic variation on organismal fitness can be affected by complex interactions including epistatic and environmental factors. To capture this impact and modern perspectives, MBE invited all members of the editorial board to reflect on how the Neutral Theory specifically impacts their own research and intellectual community. Many of our editors have made contributions and presented a broad array of views, covering theory and applications for study systems ranging from microbial to human populations. -

Haldane Haldane

THE EFFECT OF LITTER CULLING-OR FAMILY PLANNING- ON THE RATE OF NATURAL SELECTION1 JACK LESTER KING Donner Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley Received November 2, 1964. INhis classic paper “A Mathematical Theory of Natural and Artificial Selec- tion,” HALDANE(1924) devotes some space to the consideration of “those cases where the struggle occurs between members of the same family.” HALDANE termed this familial selection, citing as an example the matings of yellow by yellow mice from which litters are no smaller than normal, although one quarter of the embryos die in the blastula stage. The criteria for familial selection are that the number of survivors in each family is unchanged, although differential ge- netic deaths occur within families. HALDANE(1924) stated that “ . familial selection occasionally occurs through natural causes, but never through human agency.” However, the criteria are met whenever any arbitrary limitation of family size is regularly imposed. Ge- netic deaths which occur prior to such arbitrary limitation constitute familial selection. Compensation, the replacement of genetic losses with viable full subs. is implicit in all such cases. Four general instances suggest the need for review and further consideration of the effects of familial selection on the rate of change in gene frequencies: ( 1 ) The practice by commercial and laboratory animal breeders of culling litters to uniform sizes; (2) The use of certain breeding methods which reduce genetic drift through equal representation of each sibship ( GOWE,ROBERTSON and LATTER 1959; LUNING1960; KING 1964); (3) Certain plant genetics studies in which thinning is regularly employed; (4) The arbitrary limitation of human family size through contraception (i.e., family planning). -

Chance and Natural Selection John Beatty Philosophy of Science, Vol

Chance and Natural Selection John Beatty Philosophy of Science, Vol. 51, No. 2. (Jun., 1984), pp. 183-211. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0031-8248%28198406%2951%3A2%3C183%3ACANS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-C Philosophy of Science is currently published by The University of Chicago Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/ucpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sun Aug 19 01:27:28 2007 Philosophy of Science June, 1984 CHANCE AND NATURAL SELECTION* JOHN BEATTY? Department of Philosophy Arizona State Universitj Among the liveliest disputes in evolutionary biology today are disputes con- cerning the role of chance in evolution-more specifically, disputes concerning the relative evolutionary importance of natural selection vs. -

Evolución Molecular: El Nacimiento De Una Disciplina1

ILUIL, vol. 25, 2002, 129-158 EVOLUCIÓN MOLECULAR: EL NACIMIENTO DE UNA DISCIPLINA1 EDNA MARÍA SUAREZ DíAZ Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM (México) RESUMEN ABSTRACT El artículo reconstruye los origenes de la The paper offers a reconstruction of the Evolución Molectaar a partir de las tradicio- origins of Molecular Evolution, a discipline nes de tipo experimental, teĉrrico y descripti- tvhich arises from the interaction bettveen vista que, en la década de los sesenta, comen- experimental, descriptivist and theoretical tra- zaron a utilizar y a desarrollar técnicas ditions. /n the 60s, these different traditions moleculares para el estudio de la evolución began to use and develop experimenta/ molec- biológica. Se describe en primer lugar el tra- ular techniques to approach evo/utionary bajo realizado perr Roy Britten y sus colabo- probtems. The research carried on by Roy radores del Instituto Camegie de Washington Britten and his colleagues at the Carnegie —qtte ejemplifica el trabajo en las tradiciones /nstitution of Washington is presented at experimentales— en torno al desarrollo de las first. The developntent of nucleic acid técnicas de hibridación de ácidos nucleicos y hybridization and the stabi/ization of satel- cómo estas condujeron al establecimiento de lite-DNA are presented as examples of un nuevo fenómeno biológico: el DNA satéli- research at experimental traditions. Then, te. Posteriormente se reseña el trabajo, típico the tvork of Emile Zuckerkandl and other de las tradiciones descriptivistas, desarrollado descriptivist scientisu, such as Emmantte/ por Emile Zuckerkandl y otros científicos Margo/iash and Walter Fitch, is peresented, (como Emmanuel Margoliash y Walter Fitch) along tvith their development of mo/ecu/ar en la construcción de filogenias moleculares y taxonomies and concepu such as the molecti- el desarrollo de conceptos centrales para la lar clock. -

History in the Gene: Negotiations Between Molecular and Organismal Anthropology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Journal of the History of Biology (2008) 41:473–528 Ó Springer 2008 DOI 10.1007/s10739-008-9150-3 History in the Gene: Negotiations Between Molecular and Organismal Anthropology MARIANNE SOMMER ETH Zurich 8092 Zurich Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. In the advertising discourse of human genetic database projects, of genetic ancestry tracing companies, and in popular books on anthropological genetics, what I refer to as the anthropological gene and genome appear as documents of human history, by far surpassing the written record and oral history in scope and accuracy as archives of our past. How did macromolecules become ‘‘documents of human evolutionary history’’? Historically, molecular anthropology, a term introduced by Emile Zuckerkandl in 1962 to characterize the study of primate phylogeny and human evolution on the molecular level, asserted its claim to the privilege of interpretation regarding hominoid, hominid, and human phylogeny and evolution vis-a` -vis other historical sciences such as evolutionary biology, physical anthropology, and paleoanthropology. This process will be discussed on the basis of three key conferences on primate classification and evo- lution that brought together exponents of the respective fields and that were held in approximately ten-years intervals between the early 1960s and the 1980s. I show how the anthropological gene and genome gained their status as the most fundamental, clean, and direct records of historical information, and how the prioritizing of these epistemic objects was part of a complex involving the objectivity of numbers, logic, and mathe- matics, the objectivity of machines and instruments, and the objectivity seen to reside in the epistemic objects themselves. -

POLYALLELIC MUTATIONAL EQUILIBRIA HIS Paper Is

POLYALLELIC MUTATIONAL EQUILIBRIA JACK LESTER KING Aquatic and Population Biology Section, Department of Biological Sciences, University of California at Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, California 93106 AND TOMOKO OHTA National Institute of Genetics, Misltima, Japan Manuscript received June 25,1974 Revised copy received November 4, 1974 ABSTRACT A new deterministic formulation is derived of the equilibrium between mutation and natural selection, which takes into account (a) the possibility of many allelic mutation states, (b) selection coefficients of the order of magni- tude of the mutation rate and (c) the possibility of further mutation of already mutant alleles. The frequencies of classes of alleles 0, 1, 2, n mutant steps re- moved from the type allele are shown to form a Poisson distribution, with a mean and variance of the mutation rate divided by the coefficient of selection against each incremental mutational step. -- This formulation is inter- preted in terms of the expected frequencies of electromorphs, defined as classes of alleles characterized by common electrophoretic mobilities of their protein products. Electromorph frequencies are predicted to form stable unimodal dis- tributions of relatively few phenotypic classes. Common electromorph fre- quencies found throughout the ranges of species with large population sizes are interpreted as being a uniquely electrophoretic phenomenon; band pat- terns on starch and acrylamide gels are phenotypes, not genotypes. It is pre- dicted that individual electromorphs are highly heterogeneous with regard to amino acid sequence. HIS paper is presented in four sections: in I, a new formulation of the equi- Tl ibrium between mutation and selection is presented; in 11, this formulation is extended to predict equilibrium electrophoretic mobility class (electromorph) frequencies.